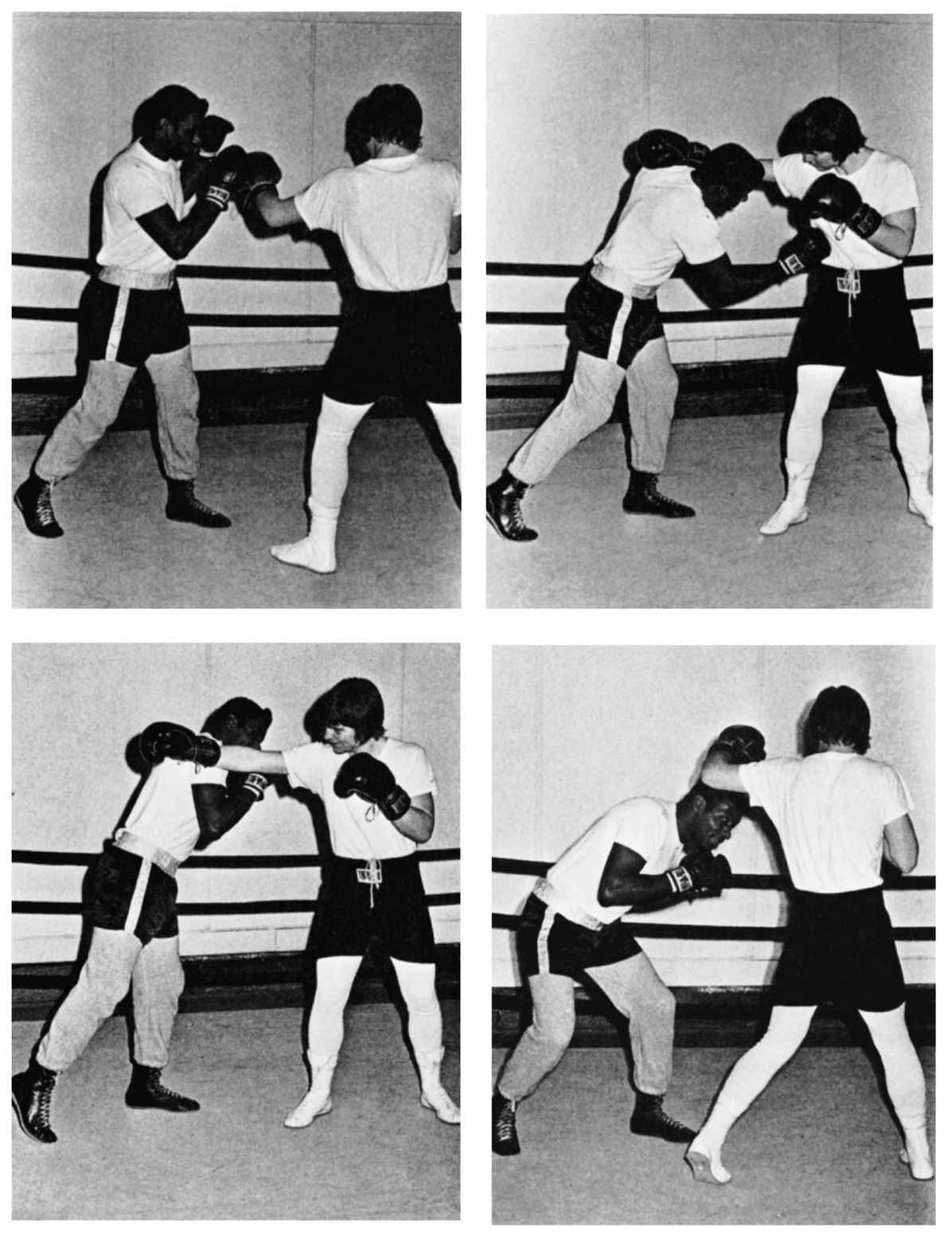

PICKING OFF PUNCHES . . . requires quick reflexes. When properly done, it gives the fighter a psychological and strategic edge over his opponent.

4

DEFENSE

Defensive moves are the tactics a boxer uses to avoid getting hit solidly. These include such moves as blocking or slipping punches, moving out of range, or moving inside the arc of a punch. It is important to learn the proper defensive moves. No matter how hard a hitter you are, or how strong, you will one day come up against someone who will be able to handle your punches and who may hurt you. That’s when you must apply your knowledge of defense and defensive tactics. Even the unbeaten Rocky Marciano was knocked down twice, though he got up to beat both men—Walcott and Moore.

When a punch is thrown at you, you have a choice of several different ways of avoiding it. You can block the punch with your hand, arm, elbow, or shoulder. Or you can pick it off with your glove, sometimes called parrying. Another choice is to go with the punch, moving your head in the direction of the punch.

SLIPPING PUNCHES

The big advantage to slipping or ducking a punch instead of blocking or parrying it is that you still have both of your hands free, ready to counterpunch.

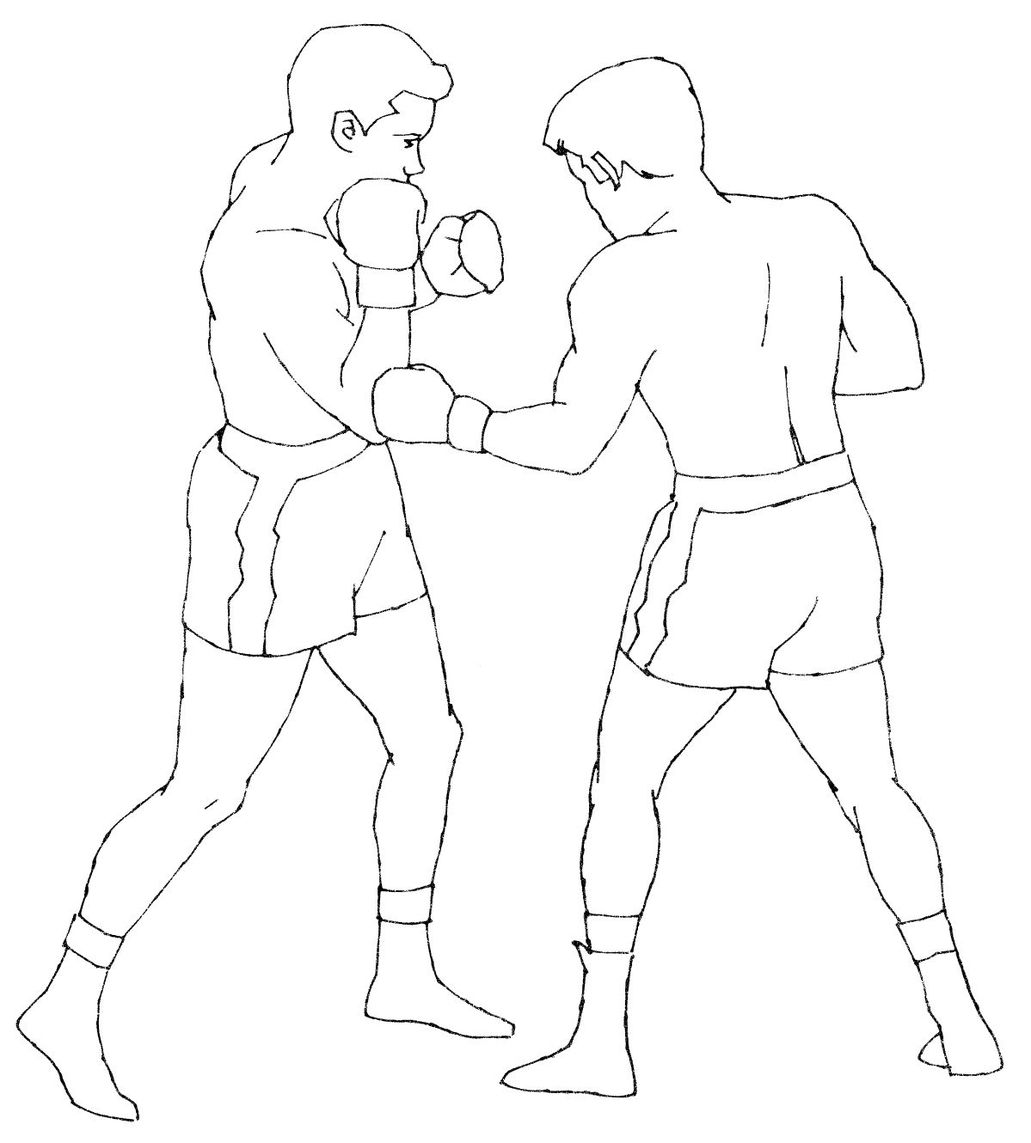

The proper way to slip a punch is to move to the inside line. In other words, to avoid a right punch, move your head to the right, and to slip a left, move your head to the left (Diagram 10). This leaves you in the perfect position to counterpunch. If you move to the outside—that is, to the left when your opponent throws a right or to the right when your opponent throws a left—your opponent’s arm will be blocking you. He may even have hit you as you moved into his punch.

Bobbing and weaving is an effective technique in slipping punches, one that I like because it allows me to come up swinging. Learning to punch from a bob and weave takes practice, but the defensive and offensive advantages it gives you make it well worth the effort. When bobbing and weaving, alter your moves. If you keep making the same moves over and over, it won’t take your opponent long to figure you out. When bobbing and weaving, I always watch my opponent’s chest. By doing so I can tell what punches he is going to throw. I can also tell approximately where his head is so that I can go on the offensive quickly and land my own punches. I try to slip beneath a right or a left or a combination of punches to get in close and initiate infighting.

DIAGRAM 10. Slipping a punch.

BLOCKING, PICKING OFF, SLIPPING, AND DUCKING PUNCHES . . . are the most important defensive moves. Use your arms as well as your hands in blocking. All of these moves depend on quickness and proper balance.

When you first start boxing, you may find that you instinctively pull your head back when you see a punch coming. This can be very dangerous. The only fighter I’ve ever seen who gets away with this is Cassius Clay (Muhammed Ali). But, unless you have great speed, you’ll get into trouble by pulling back, because it upsets your balance.

Another reaction to avoid is moving straight back when your opponent charges in. It is much more effective, and just as easy, to move to the side, getting off a counterpunch at the same time.

BLOCKING PUNCHES

Blocking or picking off a jab, or parrying, can be done in either one of two ways, depending on the type of jab being thrown at you. If the jab comes straight from your opponent’s shoulder, extend your left arm sideways from the proper stance position, just enough to knock or brush the blow to the outside. If your opponent is jabbing from a lower guard position, you can either catch the jab in the open palm of your right glove or press downward with your right, knocking the blow down and away from you.

In blocking a hook, keep your elbows in tight next to your body. Hold your arms slightly in front of you so that if the blow is to your head you can just raise your arm slightly, and if the blow is aimed at your body you can absorb the force of the punch on your arm by bending your body just a little (Diagram 11).

DIAGRAM 11. Blocking a hook.

When blocking any punch thrown at the body—whether it be a left hook, a right uppercut, or a straight right jab—always use only one arm to block the punch. If your opponent throws a left hook to your body, use your right elbow to block it. If he throws a straight right, use either your right or your left elbow to block it. If you use both arms to block a punch, you’ll leave your ribs wide open (Diagram 12).

To block a right cross or a straight right, use your left arm in an outward motion, pushing the punch away from your body. This technique is used to counter the classic jab. No mat-ter what punch your opponent throws, try to block it by forcing his arm to the outside, leaving you in the best position to counter.

DIAGRAM 12. Blocking a punch thrown at the body.

There are all kinds of variations on defense. My so-called peek-a-boo style is one of them. I keep both hands level, holding them a few inches in front of and to the side of my head. This allows me to use my gloves to block punches thrown at my head and to use my elbows to block body punches.

MY ″PEEK-A-BOO″ DEFENSE . . . allows me to use my gloves to block punches thrown at my head and my elbows to block punches thrown at my body.

Archie Moore used to fold his arms with his elbows pointing out across his body. He hid behind his arms in what he called his “Armadillo” defense. Each of you will discover what’s best for you after a while. But first, learn the “book” method so that you have a base from which to improvise.

COUNTERPUNCHING

Sometimes the best defense is a good offense. Counterpunching is the way you go onto the offensive from being on the defensive. Remember, any time your opponent throws a punch, he creates an opening for you. Counterpunching is the art of exploiting these openings and turning them to your advantage.

Let’s say that your opponent is throwing a left jab at your face. What are your options? One—you could block his left jab with your right glove and throw a jab, either taking his jab or deflecting it to the outside in a swatting motion with your own left. Two—if you are just sizing up your opponent early in a fight, you might just want to slip the punch to the side or simply move out of range. This will allow you to see if he brings his left back to the proper position or leaves it low after he punches. If he leaves it low you can come over it with your own right the next time he jabs. Slipping the punch also gives you the chance to see how fast or slow his punches are.

Nobody can keep from getting tagged forever, no matter how fast and clever and elusive he is. Years ago, people used to talk about what a great defensive boxer Willie Pep was. And believe me, he was really great. They used to say that it was practically impossible to hit Willie anywhere but on the seat of his pants. But if you take a good look at Willie today, you’ll know he stopped a few punches with his face. There is no such thing as a perfect defense.

THE CLINCH

Suppose your efforts to avoid punches have been unsuccessful. You’re on the defensive, all right, but you’re catching your opponent’s leather. What do you do in that case? Desperate situations call for desperate solutions. Try to tie your opponent up in a clinch. Clinching means holding your opponent’s arms so that he cannot strike a blow. By moving in on your opponent and pinning both of his arms to your body with your arms entwining them on the outside, you can gain additional time after missing a blow. Gaining time can be especially crucial when you’re hurt or tired. I don’t normally advise boxers to hold, and I don’t use this tactic much myself, but you should know about it as a method for getting a breather and as part of your defensive makeup.

In the final analysis, defense is a matter of instinctive self-preservation. It is up to you to sharpen your instincts by knowing all of the fundamentals of defensive boxing.