BOOST YOUR SAVING PAINLESSLY – HOW AND WHERE

In which we . . .

• Learn saving tricks

• Admire some super-savers and worry about over-savers

• Find out why today’s interest rates aren’t so pathetic

• Learn a quick way to tell how well your property has grown

• Head overseas with your savings

• Understand why individual shares are not great for most of us

• Contemplate a landlord’s nightmare

• Know where to go if you’re hard done by

• Become aware of all the scammers’ tricks

We’ve got your KiwiSaver set up and working brilliantly. Now it’s time to save more. If you’re one of the ones who’s better off doing that in KiwiSaver – you’re on a low income or you’re a big spender or you like to keep things simple – that’s fine. If not, we’ll look at other options in a minute.

But first, for everyone: how do you boost your saving rate?

Hot tips on how to become a big saver

Open a separate savings account in your bank. If they have an interest-earning account in which you pay penalties if you make too many withdrawals, that’s even better. Then:

• Set yourself a goal. See ‘A quick reminder’, below.

• Pay yourself first. Set up an automatic transfer into the account every payday – or every week or month if you don’t get regular income. Then think in terms of spending what you haven’t saved, rather than saving what you haven’t spent.

• Start small, with maybe as little as $10 or $20. Gradually increase it – perhaps by $10 on the first of every month.

• Play mind games. Imagine you’ve lost your job and your new job pays 5% less. You would manage because you would have to. So increase the automatic transfer by 5% of your pay.

• If your expenses decrease – perhaps you’ve just paid off a loan, or quit smoking (well done!), or you discover a cheaper electricity company, or a child leaves home – boost your savings by half the extra money. (This is a one-way street. When your expenses rise, don’t reduce your savings. Live with it!)

• If the government cuts taxes, save the extra take-home pay, or at least part of it.

• If you receive a one-off payment – an inheritance or a win – celebrate with a small portion but use the rest to really boost your savings.

• Find a picture that symbolises what you’re saving for. Perhaps it’s the Eiffel Tower in Paris, or a back in a beautiful bay. Put the picture where you’ll notice it often.

• Promise yourself that every time you get a pay rise – in your current job or when you start a new job – you’ll add half the extra money to your regular savings.

The last item is based on the research of University of Chicago Nobel Laureate Richard Thaler. He’s a great thinker about how real people live, and he says many of us find it hard to increase our savings out of our current income.

It’s easier to deny yourself in the future than now, says Thaler. ‘For example, given the option of going on a diet three months from now, many people will agree. But tonight at dinner, that dessert looks pretty good.’

But if you promise yourself to ‘save more tomorrow’, it works. Design your own scheme – which could apply to a decrease in expenses or a tax cut as well as a pay rise – and stick to it.

A quick reminder

Remember back in Step 2: ‘Kill off high-interest debt’ we talked about setting a goal to get rid of debt? The same tips apply to setting a savings goal.

Goals that work are SMART: specific, measurable, achievable, (w)ritten and time-bound.

It’s a great idea to promise yourself to save a certain amount by the end of the year, and perhaps another much larger amount ten years from now. Give yourself small rewards when you reach milestones towards your goal.

Champion savers

I’m hesitating to write this. A while back I ran a reader’s letter in my Weekend Herald Q&A column from a woman who had managed to save up to buy a house on an income of $30,000 a year.

In the following week, two readers wrote angry letters to me. One ran along the lines of: ‘It’s all very well for some people, but we’re trying to raise children, and we can’t make the sort of sacrifices that woman has made.’ The other was much the same, except, ‘We’re old and in ill health, and we can’t . . .’ But other readers wrote to say she had inspired them.

So let me be clear – I’m not saying everyone should be able to save this well. I’m just saying some determined people can achieve extraordinary savings. Here are a few:

True tale: Where there’s a will there’s a way

Sharil N of Auckland saves nearly two-thirds of her after-tax income. She says:

‘I am on $45,000 after tax, but work six days a week, sometimes 12-hour shifts to get it. I live in Auckland on a $600 fortnightly budget which has allowed me to save $29,000 for the last few years, but it was less in previous years due to being on a lower income.

‘Flatting helps keep rent costs down; living close to work keeps transport costs down; shopping in bulk, buying value brands and cooking at home helps the grocery bill. Little inconveniences equal big savings over time.’

Jo T and her partner, an Invercargill couple in their early thirties, are saving for a house:

‘My partner earns a good income of $70,000 a year, which we can afford to live on comfortably for the two of us.

‘Our idea is to save my income of $63,000 (around $40,000 cash in hand after KiwiSaver, student loans and tax) for the next two years. We have already saved $64,000 from living just off his income for the last two years when I was in a lower paying job.’

The woman who bought the Auckland house in 2018 while earning $30,000 says:

‘Own a 14-year-old car and never eat out. Cook meals in batches to store in freezer. Always check pricing of meats, vegetables and fruits. Don’t like alcohol, coffee and snacks. Make use of off-season deals when travelling once in two years. Avoid Boxing Day or Black Friday sales like a plague (haha).

‘Switch power and internet to cheaper providers such as Flick and Big Pipe. Wear undergarments, clothes or shoes until seeing holes before replacing them. Always do window shopping for exercise purposes. Look for ways and means to save money, for example, cutting my own hair.

‘Three years ago, bought a 4G Samsung mobile phone for $99 (on special offer) and top up $20 each year – meant for emergency use only.

‘Have a weekly budget for groceries and challenge myself to spend less than that. Make sure each purchase is value for money i.e. watch every expense like a hawk!’

Moral: If you really want to save, you’ll find a way.

The over-savers

There are those who save too much. I’ve come across several over the years, and some people might call our champions above over-savers.

They are often single women, but not always. They want to be secure in their old age – which is fine of course – but are leading rather deprived lives in the meantime. For instance, some on pretty high incomes rarely spend much on going out. That’s a real pity. They might get hit by the proverbial bus. Even if they don’t, and live to a ripe old age, they’ve had too little fun in the meantime.

Important message to most readers: Please don’t read this as ‘permission’ to spend more and save less – unless you are an over-saver.

How can you tell? If you expect to have a markedly higher standard of living in retirement than you have now, you’re probably in that small group who I urge to get out there and live a bit more! You’re probably healthier now than you’ll be later, and you want to grab chances, as and when they arise, to enjoy life with family and friends.

True tale: ‘I would love to travel, but . . .’

A while back, a 40-year-old woman wrote to my Weekend Herald column. She’s single, earns ‘in the low six figures’, owns her home and expects to be mortgage-free in 14 years. She has $50,000 in KiwiSaver, after withdrawing money to buy her home, and is contributing 8% of her pay towards it.

‘I’m starting to wonder if I’m putting too much aside for retirement,’ she wrote.

‘I would love to travel and do some cosmetic upgrades to the house, but I’m quite conscious that the pension may not be available by the time I retire, and that I may have to rely on my own savings once I stop working.

‘Should I reduce my KiwiSaver to 4% and use the extra income for things like travel and home maintenance, or invest that extra money another way, or just continue as I am?’

I did my best to reassure her that NZ Super will continue, even if at a slightly lower rate. (More on that in Step 7: ‘Head confidently towards retirement – and through it’.) In light of that, I suggested she cut her KiwiSaver contributions to 3% and spend the extra take-home money on travel and other fun things.

When we were in touch again, some months later, she reported, ‘I reduced my KiwiSaver, and am saving for a trip to Europe later this year, which I’m very excited about! I couldn’t help but direct some of the savings into my mortgage, but I feel more relaxed about my retirement, whenever that may come about.’

Moral: Life is for living as well as for saving.

Where to save outside KiwiSaver: short-term savings

You’ve been setting aside money regularly. Great!

Every now and then – maybe every two months, or maybe when your savings account balance reaches $500 – transfer the money into an investment. But what investment?

That depends to a large extent on when you expect to spend the money.

If you think you are likely to spend it within two or three years, it’s simplest to just use bank term deposits.

Is today’s interest so terrible?

I was once sailing in a small yacht through the narrow stretch of a harbour. The sails were full and we seemed to be going full-steam – sorry, full-sail – ahead. It felt great. But when we looked at the shoreline we realised we were actually going backwards. The force of the tide was stronger than the force of the wind.

Some time later, the wind had dropped and the tide had changed. The sailing wasn’t nearly as exhilarating, but we were getting where we wanted to go.

Investing in bank term deposits in the late 1960s to early 1980s was like the first experience. It felt wonderful to earn interest well into the teens. Your savings balance zoomed up.

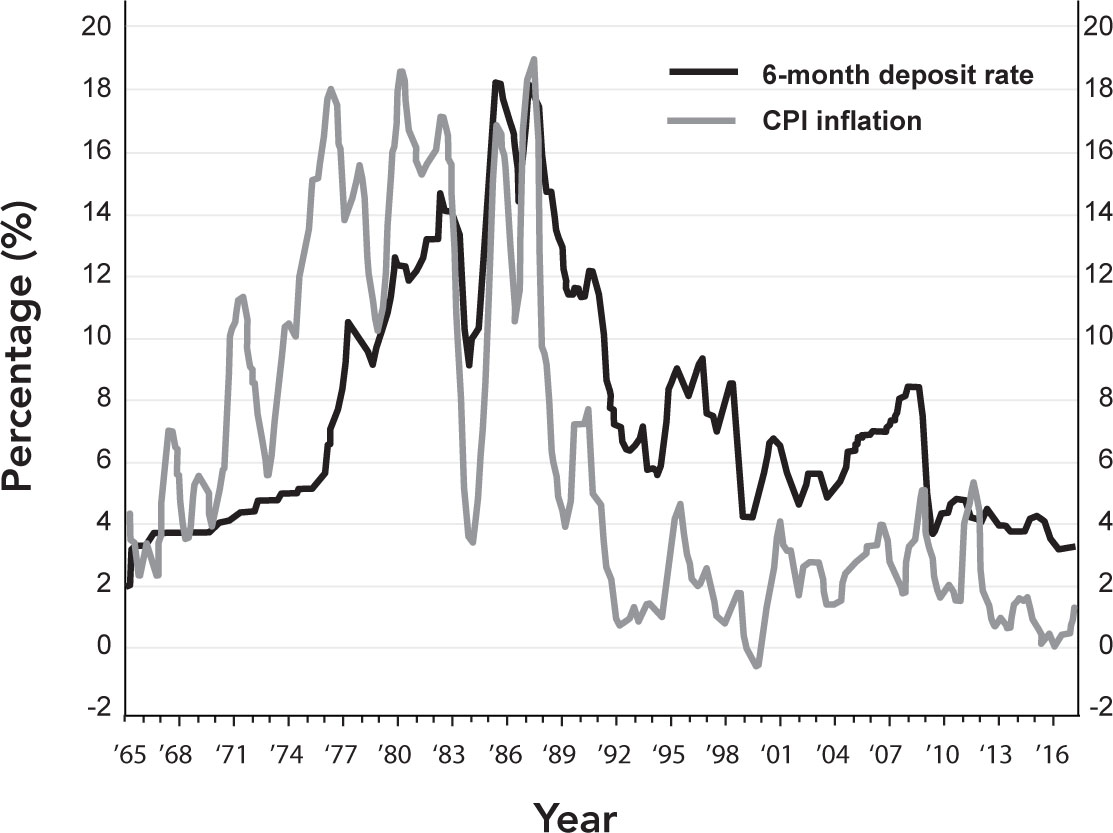

The only trouble was – as our graph shows – inflation was extremely high. This was partly because we ‘imported’ high US inflation, partly because of a huge oil price increase in 1973–74, and partly because of NZ government policies.

Importantly, inflation was higher than interest rates. Your $1,000 term deposit might be $1,120 a year later, but you could buy less with the $1,120 than you could with the $1,000 the year before. You were sailing backwards.

These days, your $1,000 might be just $1,030 a year later – at an interest rate of 3%. But with inflation below 2%, your buying power is growing. Your yacht is making progress.

And that’s all that matters with money. As anyone who has used a foreign currency when travelling knows, it’s not about the numbers, but what you can buy with your cash.

Let’s add tax into the mix. In the bad old days, after paying lots of tax on your interest you were even further behind. These days, you pay much less tax on lower interest, so you can still come out ahead after tax.

Figure 8: Inflation and interest rates – how times have changed

Inflation used to be higher than interest rates, but they swapped

Source: Reserve Bank of NZ

Note: CPI inflation shows changes in the Consumer Price Index, which measures the changing prices of goods and services that New Zealanders buy.

Which bank term deposit?

• Don’t just go with your own bank. Another bank is highly likely to offer a better interest rate. See what’s being offered under the ‘Saving’ tab at www.interest.co.nz.

• Go to your own bank and ask if they can raise their rate to match the other bank. Several people have told me that worked for them.

• If you want a bit more sophistication, consider some alternatives with somewhat higher average returns. Some banks run what are called PIE term funds, which give many people a tax break. Or you could go into a cash fund, perhaps run by a KiwiSaver provider but not part of the KiwiSaver scheme, where your money isn’t tied up. But in a cash fund your return will vary – which might be good or bad – and you’ll pay fees.

Where to save outside KiwiSaver: mid-term savings

Bonds – remember them? They’re like term deposits but issued by governments and companies. They work well for money you plan to spend in three to ten years.

You can buy bonds from a stockbroker, including online stockbroking services. Or, if that sounds too complicated, go for a bond fund. The fund manager will run it all for you, and you get a good spread of different bonds.

The next question is which bonds or which bond fund. We’ll look at the funds first.

Remember back in Step 4 where we were finding the best type of KiwiSaver fund for you? Go through the same process, even though you’re not going to use a KiwiSaver fund. This is because at this stage there’s no non-KiwiSaver tool that works as well.

Answer the questions on when you’re likely to spend the money and how much you can tolerate ups and downs in your balance. Let’s say that leads you to decide to save in a balanced KiwiSaver fund. (This may well be a lower-risk fund than your earlier KiwiSaver choice, because you’re planning to spend the money sooner.)

Next go through the same process as before to find which provider is right for you. With a different risk level, you might find a different provider is better.

Okay – you’ve now got a KiwiSaver fund selected, even though you don’t want to put this money in KiwiSaver!

Look at that provider’s website to see if they have a similar non-KiwiSaver fund. Most providers do. If you can’t find that out easily, call or email them to ask.

Before committing to a fund, you’ll want to check if they will accept contributions of the size and frequency you want to make. And how easy it is to get some or all of the money out whenever you want it. You might find it will take a few days for a withdrawal, but that probably won’t be a problem.

Take note of how easy it is to deal with the provider. If they are slack, or use a lot of financial jargon you don’t understand, give them a miss. Fund managers make plenty of money from you and me, and should make it easy for us to do business with them.

If you would prefer to invest in individual bonds, you can get a list of what’s on the market at www.interest.co.nz.

Warning: This is a bit like a Maths alert but it’s a Boredom alert. A friend reading this book told me this section made her want to put the book down. Horrors! If you’re not interested in buying individual bonds, it’s okay to skip down to the Rule of 72. But if you are a bond buyer, you’d better keep reading.

A key consideration when buying bonds is their credit rating, which is included on interest.co.nz.

Credit ratings are issued by three big international agencies: S&P, Moody’s and Fitch. They give you a pretty good idea of how likely it is that you will get your interest and your money back.

S&P and Fitch’s ratings range from AAA (extremely strong), through AA, A, BBB, BB, B and so on, down to D (in default). Moody’s is similar, but they use Aaa, Aa, A, Baa, Ba, B and so on, down to C (in default).

Sometimes a rating has a plus or minus sign after it. Look at the letters first. For example, AA– is better than A+.

The Reserve Bank, which regulates our banks, points out that credit ratings are not like marks for an essay in high school, where a B was pretty good. Instead, a B credit rating means there’s a one in five chance the institution will default over five years. I wouldn’t take that on.

It’s best to stick with what are called ‘investment grade’ bonds, which means they have a rating of BBB− (Baa if it’s Moody’s) or better. Bonds with lower ratings are sometimes called junk bonds. Note the name! They’re not called that for nothing.

Banks get credit ratings. At the time of writing, the big four New Zealand banks – ANZ, ASB, BNZ and Westpac – all had an AA− rating. Kiwibank had A and TSB had A−. Cooperative, Heartland and SBS all had BBB.

For other companies, ratings include, for example, A− for Auckland International Airport, BBB+ for Genesis Energy and BBB for Chorus. Some smaller institutions have no rating. Unless you know a lot about them, give them a miss.

The agencies give these ratings based on research, but they’re not perfect. In the global financial crisis of 2007–08, some highly rated companies went under. Still, the ratings generally give us good guidance.

For more on ratings and how to interpret them, see a clear explanation by the Reserve Bank at www.tinyurl.com/CreditNZ.

The Rule of 72

Maths alert!

The very handy Rule of 72 lets you quickly work out two things.

The first is roughly how long it will take for an investment to double. For example:

• If your investment is growing at 4% a year, divide 72 by 4. It will take 18 years to double.

• If you want to double your money in 10 years, divide 72 by 10. You will need to earn about 7% a year.

The second is useful if an investment that has doubled. Using the rule, you can work out roughly what return you’ve made. For example:

• If your house value has doubled over 12 years, divide 72 by 12, to get 6. The value has grown by 6% a year.

• If your share investment has doubled in 8 years, divide 72 by 8. The value has grown by 9% a year.

Note that the Rule of 72 works only for one-off investments – like buying a house or putting a lump sum into an investment. It doesn’t work for KiwiSaver or any other investment where you drip-feed in money over time.

The rule is an approximation. It’s most accurate for returns of 6% to 10%, and gets a bit dodgy for returns of less than 3% or more than 15%. If your house value has doubled in two years – which has occasionally happened recently – the rule says your annual return is 36%, but it’s actually more like 41%. Still, it gives you a pretty good idea.

One of the beauties of the rule is that you can divide 72 by 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 12, 18, 24 and 36, which makes calculations easier. And for other numbers, near enough is good enough.

Main point (for those who don’t like maths): This gives you a rough idea of how the numbers are working for you. But if it’s all too hard, forget it!

Where to save outside KiwiSaver: longer-term savings

We saw in the KiwiSaver step that it’s good to go for riskier investments over the long term. Your returns will probably be higher, and there’s time to recover from a downturn.

If you have money you want to tie up for a decade or more outside KiwiSaver, the same thing applies. And for most people a riskier managed fund is the best bet.

Go through the same process as outlined above for mid-term savings. Use the KiwiSaver online tools to find the best KiwiSaver fund for your long-term money, and then see if that provider offers a similar non-KiwiSaver fund.

As with mid-term savings, check if the fund you’re considering will accept contributions of the size and frequency that suit you. And check how easy it is to withdraw money.

Remember back when we were talking about choosing a KiwiSaver fund and I said it’s good if your fund has a fair bit of its share and bond investments offshore? Let’s look at this in a bit more depth.

There are two main reasons for investing beyond New Zealand. And they’re both about reducing risk. So if you’re thinking overseas investments add to your risk, think again.

Reason 1: Diversification

This means spreading your risk over lots of different investments. This idea will crop up several more times in this book. It’s really important. But here we’re talking about a specific type of diversification – spreading your investments around the world.

If you took the value of all the shares traded on the New Zealand stock exchange, the NZX, the total would be about 0.1% of all the shares in the world. That’s not one in a hundred, that’s one in a thousand. Our share market is, to put it rudely, a minnow.

What’s more, there are many industries not represented amongst NZ shares, such as cars and major electronic goods. If you confine yourself to local shares, you’ll miss out on what could be the biggest growth shares.

Some people say it’s good to stick with New Zealand shares because of what’s called dividend imputation. This is a tax credit that recognises that companies pay tax on their profits, so it’s unfair if dividends paid out of those profits are then taxed again in the hands of shareholders. But imputation is not a powerful enough reason not to invest overseas. It’s more than offset by the advantages of diversification.

When you stop to think about it, you probably have a job, perhaps a house, perhaps even more than one property in this country. That’s enough exposure to a single economy that could be crippled by an agricultural disease or a major earthquake or volcanic eruption.

It’s far safer to have some of your assets in other economies. And not just Australia. Some New Zealanders say they feel safer investing in Australia than further afield. But the Aussie and New Zealand share markets tend to move somewhat similarly. And, again, you still won’t cover a wide range of industries if you confine your offshore investing to Australia.

Put some of your savings in international investments and there’s a good chance that when our share market falls, that will be offset by gains elsewhere. Sure, the reverse happens too – that New Zealand gains can be pulled down by losses overseas. But over the long run your ride should be somewhat smoother if your investments range far and wide.

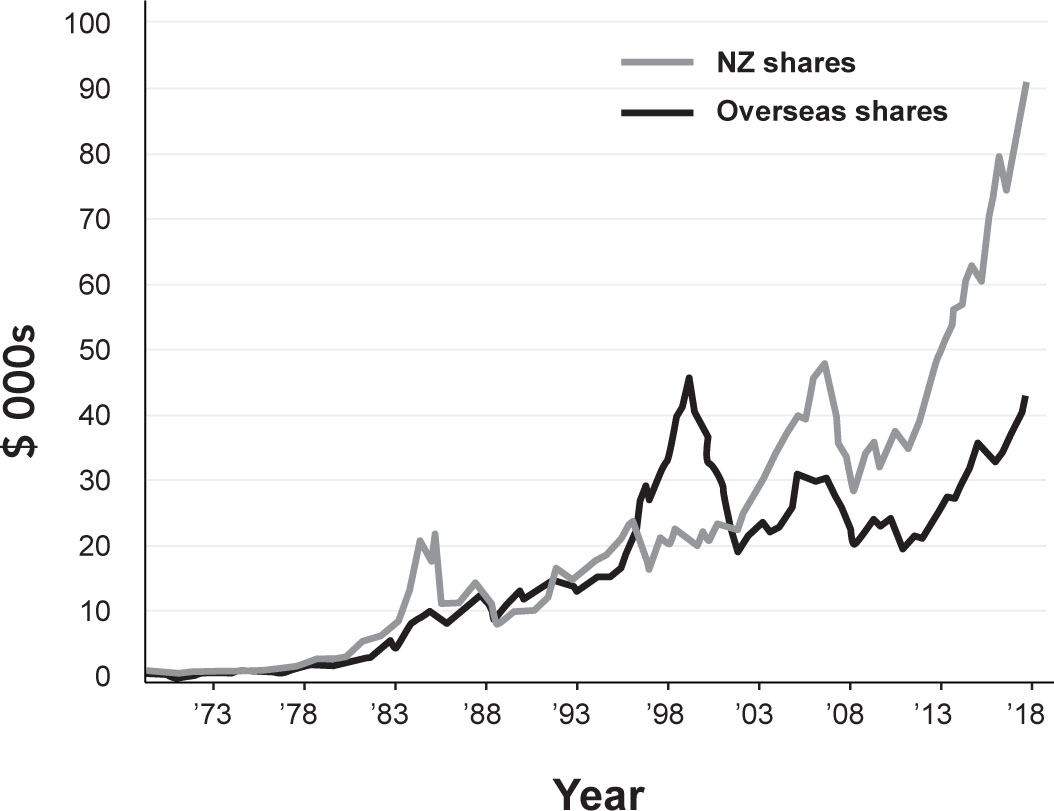

Points to notice about Figure 9:

• NZ and overseas shares sometimes follow similar paths, but sometimes very different paths.

• In both cases, there are lots of ups and downs – including some serious falls over a couple of years following really strong rises. But in the long run the trend is upwards. Figure 9 shows that if you invested $1,000 in NZ shares in 1970, and left it there to grow, reinvesting your dividends, it would have grown to $91,000 after tax. In overseas shares it would have grown to $43,000. Still pretty impressive.

• While NZ shares have grown much faster than world shares in the past decade, that could easily change. If we look back there are periods, like the late 1990s, when overseas shares grew way faster – more than doubling in just a few years. That could happen again at some point. We just don’t know.

Figure 9: Share markets don’t move together

Value of $1,000 invested in 1973 in NZ and overseas shares, including dividends (after tax)

Source: MCA

Technical stuff: The calculations for this graph don’t include costs of investing, such as brokerage if you invest directly in shares or fees if you invest in a share fund. That would reduce returns quite a lot over a long period. But they do include tax at the top PIR rate of 28% (income over $48,000). Returns would be higher for those on lower incomes, because their tax rate would be lower. NZ shares include calculations for imputation credits, as they are part of income.

Reason 2: Dollar movements

The second reason to invest offshore is to do with foreign exchange rates – the fact that the Kiwi dollar fluctuates against other dollars.

If the value of our dollar falls against other currencies, the value of any investments you have offshore rises. And the reverse also happens – if our dollar rises, offshore investments fall. Just remember: they move in opposite directions.

That might sound worrying, but it’s not really, especially when it comes to your retirement savings. Let’s say you retire with either a mortgage-free home or a big enough lump sum to cover your rent for the rest of your life. And you also have other savings – in KiwiSaver or elsewhere.

As I’ve said before, I’m confident there’ll be reasonable NZ Super available for everyone in the decades to come. And Super should cover your basic expenses in retirement, like food, clothing and transport.

So what are you going to spend your savings on? It’s likely that quite a lot will go on things like cars, electronic goods, books – many of which are imported – as well as overseas travel.

What if the Kiwi dollar falls between now and when you spend this money? The prices of imported goods and foreign travel will rise. But, as we said above, the value of your overseas investments will also rise. That will help you pay the extra for the imports and travel. It’s a bonus you wouldn’t have had if you had stuck with just New Zealand investments.

What about the reverse? If the Kiwi dollar rises, the value of your overseas investments will fall. But the price of imports and travel will also fall (because of the rise in the Kiwi), so you won’t suffer.

Confused? Some people can get their heads around this and some can’t. But don’t worry. All you really need to know is that if you want to spend a fair bit of your savings on imports and foreign travel, you actually lower your risk by having some of your savings overseas.

But isn’t offshore investing disloyal?

Some people say we should stick with investing in New Zealand to support our companies. But I disagree. We talked earlier about disasters that could hit our economy. If an agricultural disease or natural disaster struck, it would be great if many people had offshore investments that held their value. They could then bring some money home to help get things going again here.

Even if something like that never happens – here’s hoping! – if many people are better off because they have invested overseas, that helps the whole country.

How to invest offshore

You could go to a sharebroker and ask them to sell you shares in, say, some US companies. That’s what some seriously wealthy people do. But I don’t recommend it if you want to keep your investing simple. Investing directly overseas makes things more complicated. Taxes are tricky and you will almost certainly need to hire an expert to handle them. And after you die it takes longer for your estate to be settled if you have overseas investments.

It’s easier if you invest in a New Zealand-based fund manager which, in turn, invests in overseas assets. Let them handle the tax complications and so on. Many local fund managers offer international share or bond funds, giving you ownership of teeny proportions of some of the world’s biggest companies.

How much of your savings should be offshore? That really depends on the proportion you expect to spend on imports and travel. For many New Zealanders it should be at least half your long-term savings – in or out of KiwiSaver.

Behind the hedge?

If a fund that invests overseas is fully hedged, that means the managers have taken steps so that foreign exchange movements don’t affect your investments.

While this might sound good, it would ruin what we’ve looked at above – the way having offshore investments reduces your risk if you’re planning to spend on imports and foreign travel. So I would recommend avoiding hedged investments – or at least fully hedged ones – unless you don’t expect to travel overseas much or buy imported goods. A good compromise for some people is a fund that is 50% hedged.

Other investments – individual shares and rental property

How come I haven’t suggested individual shares or rental property for longer-term savings? Both can be good investments, but . . .

Individual shares

I’m not keen on sending you off to a sharebroker – online or otherwise – to buy shares in This Company or That Company. Unless you have, say, $100,000 or more, you can’t realistically buy shares in a wide range of companies. And concentrating on a few shares raises your risk. It’s great if they do well, but they could easily not.

Remember I said back in the KiwiSaver step that most people – arguably everyone – is no good at consistently picking which shares will do well. If the experts can’t do it, do you really think you can?

I often hear from people who say something like, ‘Hang on a minute. I’ve invested directly in shares and look how well I’ve done over the last ten years.’ What they don’t realise is that the share markets as a whole have been performing well. Everyone in share funds has also seen their investments rise healthily. In fact, any direct share investor who hasn’t done well over that period should be ashamed!

There’s another issue, too. If you own your own shares, you need to keep track of dividends, and sometimes there are issues on which shareholders are asked to vote and other complications. Some people – like my father – make a hobby of following all that. But most of us are better off in a share fund, leaving the managers to deal with that stuff.

Grab the bargains

Every now and then you’ll either be given shares or get an opportunity to buy them at below market price. It might be because a power company or insurance company is changing its structure, or your employer is offering you shares in the company.

Generally, I would grab those chances. But then sell the shares as soon as you can.

If it’s an employee stock ownership plan, the company may require you to keep the shares for several years. Your bosses want you to feel more involved in the company as one of its owners. And I have to say that when I’ve been in one of these schemes it did work to some extent; I wanted the company to do well.

But still, I suggest you sell when you’re allowed to. Let’s say the shares are worth $1,000. Consider what you would do if you inherited $1,000 in cash. Would you invest it in your employer’s shares if you were buying them at the market price? Almost certainly not. So don’t hold on to them. Sell them and perhaps invest in a share fund.

Rental property

Ah, rental property! It’s the great love of many New Zealanders, quite likely including you or your parents or friends. And there’s no denying that a lot of people have profited handsomely from investing in rentals.

Perhaps because of that, over my years as a columnist, the harshest criticism levelled at me has come from big fans of rental property. I’ve ‘got it in for’ property, they say. None of them has ever come up with why I would be that way. I don’t get anything – money or love – out of being ‘anti-property’.

The fact is that I’m not anti it. I did do disastrously with one house – which you’ll read about shortly. But apart from that, I’ve done really well out of buying and selling homes over the years. The value of one property, in Sydney, almost doubled in just two years.

We should all be wary, though, of stories about huge gains people have made in property. The gains on your home can be pretty meaningless if you’re selling it and buying another in the same market. Both prices have risen, and you’re not really getting ahead.

But with rentals, the stories sound wonderful. We’ve all heard people say they bought a property for, say, $300,000, and sold it just three years later for twice that – sometimes even more.

I’ve got three responses to that:

• They had good luck with their timing. The property market happened to rise fast in that period – perhaps boosted by a rare plunge in mortgage interest rates like the one we saw in 2008–09. We won’t see that again for a long time, because rates can’t go down much more than they are now.

• They are perhaps not telling you about their other property investment in a different period, when the value fell or went sideways.

• People often forget about all the money they’ve put into a rental property while they owned it. It’s common for mortgage payments to be bigger than rental income. And then there’s rates and insurance, plus occasional large sums for repairs or to redecorate. If you buy a property for $500,000 and then spend $300,000 on it and sell it for $900,000, you didn’t make $400,000. Oh, and by the way, your profit should be taxable, and it’s increasingly likely that will be policed.

The thing about property is that while some people do really well out of it, it’s riskier and more complicated than many people realise. Everyone knows shares are risky, but rental property can be more so. Read on.

When borrowing to invest goes wrong

Most people have to borrow to buy rental property. Sure, you borrow to buy your own home too. It’s a rare bird who buys their home with cash. But the very fact that you’ve borrowed to buy your home means it’s not a great idea to boost the borrowing to buy a rental property as well.

Key message: Borrowing to invest – sometimes called gearing – is risky.

Gearing is great when things go well. You get the gain not only on the money you put in, but also on the bank’s money. Some people have built fortunes on this. But gearing is a bit like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s little girl – ‘When she was good she was very good indeed, but when she was bad she was horrid.’

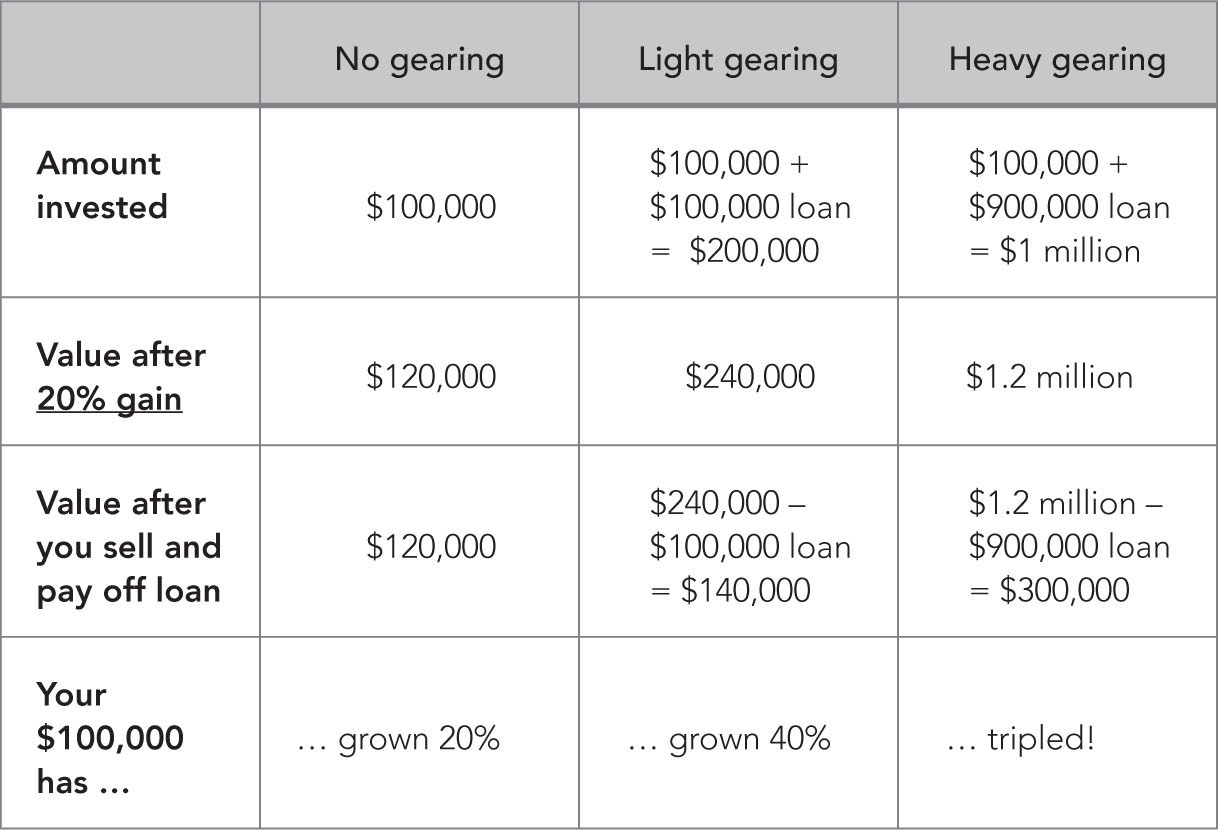

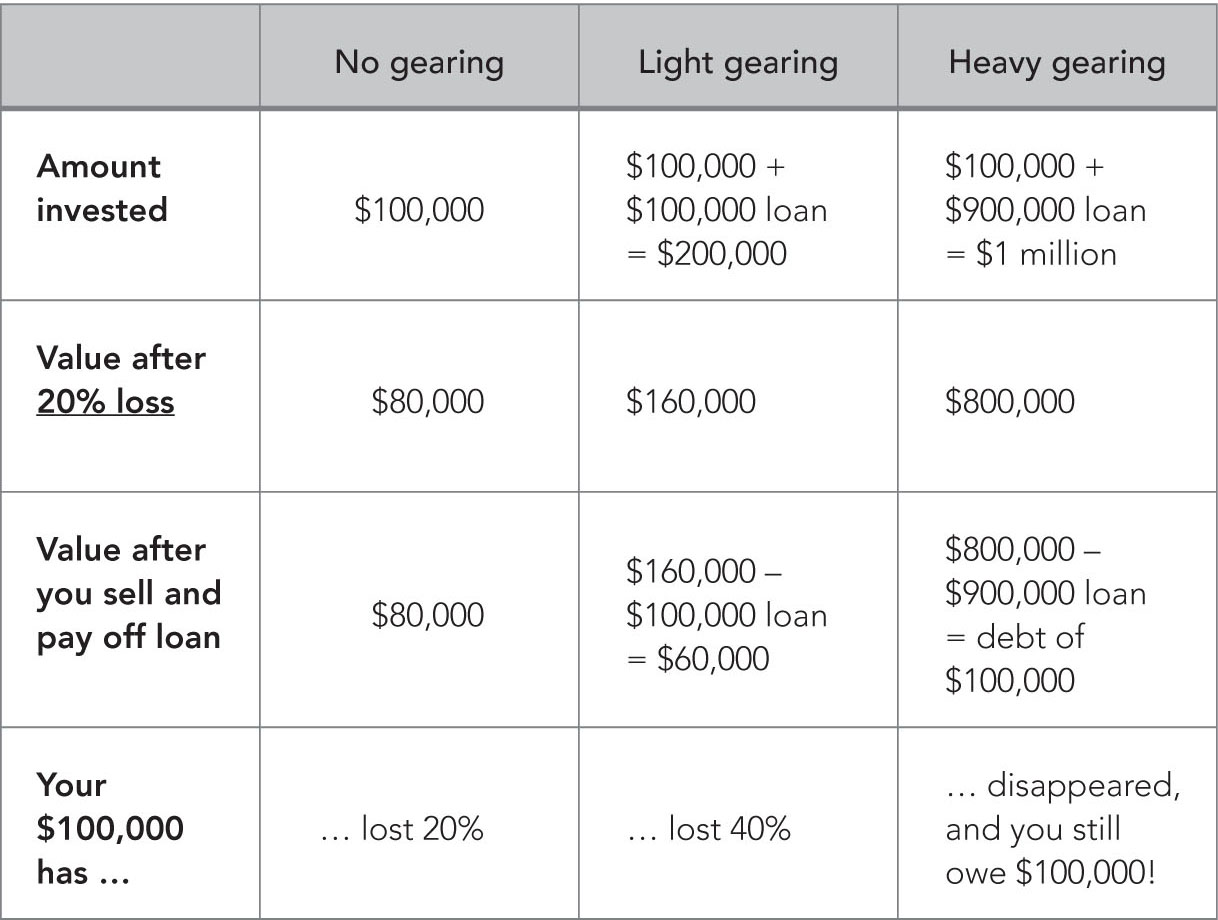

This applies to borrowing to invest in anything – shares, emus or property. But few people borrow to invest in shares or emus. Gearing is mainly a property thing. And, as Figure 10 shows, the more you gear, the more you stand to gain – or lose.

Before you start to look at Figure 10, note that it simplifies things. To make it easier to follow, we don’t bother with interest on the loans, or loan repayments, until you sell. (After Figure 10, we’ll look at how including those would affect things. But for now, please bear with me!)

In Figure 10, you start with savings of $100,000.

With no gearing, in our lucky scenario the balance rises by 20% to $120,000. There’s no loan to pay back, so you end up with the $120,000. But in our unlucky scenario, the balance falls by 20% over time. You end up with just $80,000.

Next we look at light gearing. In the lucky scenario, the investment gains 20% so you end up with $240,000. After you pay back the $100,000 loan, you have $140,000 left. Your original $100,000 has grown by 40%. You’ve done twice as well as you would have with no gearing. Great!

But if things go badly – as in the unlucky scenario – your $200,000 drops 20% to just $160,000. And that’s not all. By the time you pay back the $100,000 loan, you’re left with just $60,000. That’s 40% down on your original $100,000. Not so great.

Figure 10: What happens when you gear

The lucky geared investor: starting with $100,000

The unlucky geared investor: starting with $100,000

Heavy gearing is typically for buying property. In the lucky scenario, after a 20% gain, your $1 million has turned into $1.2 million. You pay back the $900,000 loan and are left with $300,000. Your original $100,000 has tripled. Wow! That’s way better than with no or low gearing.

But the unlucky scenario is very unlucky. A 20% loss turns your $1 million into just $800,000. And then you’ve got to repay a $900,000 loan. You sell the property for $800,000, but you’ve still got to come up with another $100,000 from somewhere else. Things have gone horribly wrong. The heavier the gearing, the bigger the risk.

Maths alert! As noted above, the tables in Figure 10 don’t include interest, or loan repayments until you sell. If we included interest, the gains from gearing would be smaller and the losses bigger. But this would often be offset by rental income (or if you had borrowed to invest in shares, dividends.) So it probably wouldn’t make much difference to the outcomes in the tables. It would just make it much harder to follow!

If we included loan repayments, that’s really just a separate savings program. For every dollar you repay, you have one more dollar of equity in the property, and so you reduce your gearing. But it doesn’t affect the basic idea of gearing.

Main point: Gearing makes a good investment better, but a bad investment worse. In other words, it increases your risk.

‘Sure,’ say the keen rental folk, ‘but you don’t make losses on rental property.’

Let me paint a few pictures. What if . . .

You have to put extra into your mortgage payments because the rental income isn’t enough – a common situation – and you lose your job? Or the tenants stop paying? (Even the nicest ones might suffer a cash crisis.) Or you don’t have any tenants for a while because you can’t find good ones? Or you find the house is leaky – or worse still, all three units you bought in a new high-rise are leaky? Or the place has been used as a meth lab, or for any number of other reasons you suddenly need to spend a lot on it? Or mortgage interest rates rise fast. Just ten years ago, average two-year fixed mortgage interest rates were above 9% and floating rates were above 10%. It could happen again.

And what if several of those disasters happen at once?

All sorts of situations arise in which landlords find they have to sell their rental property unexpectedly, quite often when the economy isn’t great. That may be why you lost your job and your tenant lost their job in the first place. And, contrary to popular belief, property prices sometimes fall. It’s odd how quickly people forget that, but it does happen, as Figure 11 shows.

Every time there’s a property downturn, not only are some landlords forced to sell, but they sell for less than their mortgage. They end up with no asset and a debt. I’ve known people that has happened to. It’s not pretty.

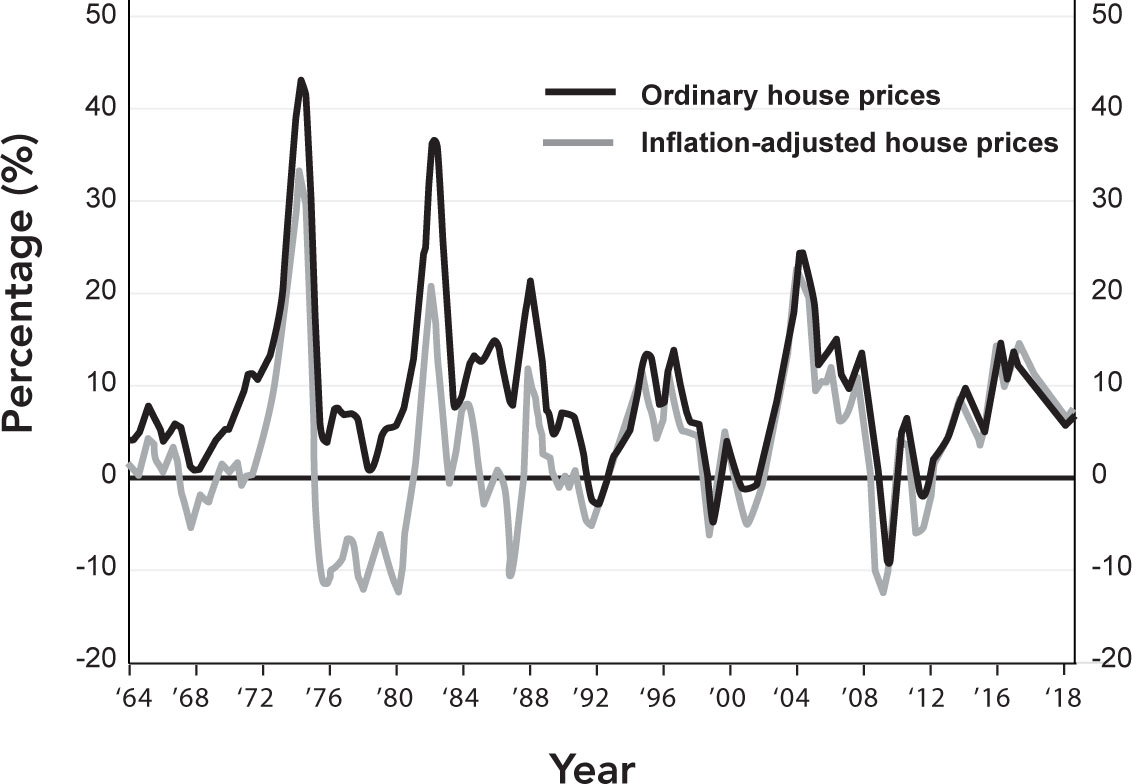

Figure 11 shows ordinary house prices and also house prices that have been adjusted for inflation. That second lower line shows how much house prices have grown when we remove inflation from the mix.

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, inflation was high – as you can see by the big gap between the two lines. So, ordinary house prices didn’t fall, although prices adjusted for inflation did quite often. Now, with inflation much lower, even ordinary house prices have fallen (the line drops below zero) several times in the past 30 years.

Figure 11: House prices sometimes fall

When line goes below zero, prices have fallen

Source: Reserve Bank of NZ

Other downsides of rental property

• Being a landlord can be a hassle. If something goes wrong with the property or with the tenants, you’d better get it fixed fast. Of course you can hire a company to do that, but their fee eats a big hole in your profits.

• Government changes. Politicians of all stripes have been saying for years that too many New Zealanders put their savings into rental properties. So the politicians are constantly looking into changing mortgage rules, housing standards and taxes to discourage that. Changes made in March 2018 have meant that gains on newly bought rentals that are resold within five years are taxed. Also, under mortgage regulations, you usually need a much bigger deposit to buy a rental than to buy your own home. The trend towards more regulation is likely to continue.

• It’s more complicated to get cash out of a property investment than out of shares or a share fund. Also, it usually takes a lot longer to sell a rental property. If you need the money in a hurry, you could find yourself selling the rental for a low price.

• Lack of diversification. If you own your own home and a rental, you’ve got a huge exposure to property. And if the rental is near your home – and understandably many people like that – you’ll be hit doubly if values in the area deteriorate. That does happen – in any neighbourhood. (See ‘True Tale’, page 140.) To avoid that risk, you could buy your rental somewhere distant from your home. But then you’re not Johnny on the Spot when things go wrong.

• You can’t drip-feed into the investment. Many people think they can pick the best time to buy a property, but they’re often wrong. Timing any market is pretty much impossible. (More on this in Step 6: ‘Stay cool’.) A good way to get around this problem is to drip-feed your money into an investment, but you can’t do that with property. And if prices fall soon after you purchase, it’s much harder to sell later at a gain.

If you want to go ahead anyway

Having said all that, rental property works well for some people – particularly those who enjoy maintenance work and doing up houses, and are happy about being firm with difficult tenants.

If you’re already a landlord, good on you! I hope none of the bad things listed above ever happen to you. If you’re just at the ‘thinking about it’ stage, be aware of what you might be getting yourself into.

Some rules for the determined would-be landlord:

• Avoid buying when everyone else is buying – or has bought recently. If you’re jumping on a bandwagon, you’re likely to pay too much.

• Avoid mortgaging your home to buy a rental. If things go wrong, you could end up losing your home.

• Plan your cash flow – when the dollars will come in and when they will go out. Flick back a few pages to the heading ‘When borrowing to invest goes wrong’, and find the paragraph that starts ‘Let me paint a few pictures’ (page 136). How would you cope, cashwise, if one or more of those bad things happens? It’s wise to work through a worst case scenario.

True tale: Can you top this loss?

The biggest loss I’ve ever taken on a property was in the smart Auckland suburb of St Heliers. We had bought the house for $385,000 just before the 1987 share market crash.

A couple of years later we wanted to move elsewhere. To our dismay, we got only $270,000 for the place – a 30% drop. How come? A lot of people in that suburb had been ruined by the crash and had to sell their houses in a hurry, and that had dragged down the market.

Moral: House values can fall a long way even in ‘nice’ suburbs.

What about gold and other investments?

Every now and then, usually when the share market has the wobbles, some people rush to invest in gold. They say things like, ‘It’s the only investment you can count on if the world falls apart.’

Really? After Armageddon, when nobody has shelter or enough to eat, what good will a chunk of shiny metal be? As Warren Buffett has put it, ‘Gold gets dug out of the ground in Africa, or someplace. Then we melt it down, dig another hole, bury it again and pay people to stand around guarding it. It has no utility. anyone watching from Mars would be scratching their head.’

Some people debate this, but in any case we’re assuming your gold investment is actually in the metal itself, as opposed to the more common form of gold investment – in a gold fund or similar. That would be as useless as shares.

The facts are:

• The gold price is as volatile as share prices. Big drops are not uncommon. And the price tends to keep falling for much longer than share prices.

• Gold doesn’t produce any ongoing returns. Bonds pay interest, shares give you dividends, property gives you rent, but gold gives you nothing until you sell it – hopefully at a gain. If prices have fallen when you have to sell, it could look like a pretty lousy investment.

Having said that, if you really want to put a small percentage of your savings in gold, I wouldn’t argue with you. To some extent gold rises when shares fall, and the reverse, so it does spread your risk a bit.

Many other investments, though, are just fads. People have made and then lost a lot on things like emus. What about bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies? The jury is still out. If I say, ‘Give it a miss’, and then you hear of people making huge profits, you might get mad at me. But then again you might be really glad you read this warning. Let’s just say I’m staying away.

Stuck in a battle with a bank, insurance company, financial adviser, stockbroker, credit union, KiwiSaver provider, lender, credit card provider, finance company or anyone else who provides a financial service in New Zealand? One of the country’s four financial dispute resolution schemes may be able to help you. And their help is free.

The four schemes are:

• Banking Ombudsman Scheme (BOS);

• Financial Dispute Resolution Service (FDRS);

• Financial Services Complaints Ltd (FSCL); and

• Insurance and Financial Services Ombudsman (IFSO).

Every financial services provider has to belong to one of the schemes, and has to tell you which one it belongs to. In many cases it will be written on their website or in their literature. You can also find out by looking at the register on the Companies Office website, at www.tinyurl.com/NZRegister.

Before you approach the scheme, you have to discuss your problem with the financial company. But if you’re not happy with how it’s been resolved, it’s time to go to the dispute resolution scheme. You’ll be asked for your side of the story, and so will the provider. The scheme then makes a decision that the provider can’t wriggle out of. But if you’re unhappy with it, you are free to take other action, such as going to court.

The schemes pride themselves on being fair to both sides of a dispute. However, at first glance the figures on their decisions might seem discouraging to consumers, as more decisions tend to go against consumers than for them (although many decisions are half and half). But this is because, if the provider has clearly been wrong, they will tend to settle a dispute before it gets to their dispute resolution scheme.

Still, there are many decisions fully or partly in favour of the consumer. And even when that’s not the case, many consumers have reported they are content with the outcome because they’ve learnt more about why the problem arose.

For more on how the schemes work, and examples of cases they’ve looked into, see their websites. There are some fascinating stories there.

Disclosure: I’m on the board of FSCL, representing consumers, and I used to be on the board of the Banking Ombudsman Scheme. If they were for-profit organisations, I could be accused here of trying to drum up business for them. But they’re not!

I think what the four schemes do is great, but their work is too little known. I urge you to use them when you need to, and to tell others about them.

While dispute resolution schemes can help you with problems with New Zealand-based financial services providers, usually they can’t help if you’ve been ripped off by a locally based crook. And they almost certainly can’t help if it’s an offshore company. You’ll have to go to the police or a government agency – and even then you might find they can’t do much, especially if it’s an overseas scam.

It’s far better to avoid being ripped off than to try to remedy things after the fact.

9 warning signs of scams

Here are some flashing lights that say, ‘Keep away!’

Warning sign 1: The return is expected to be higher than, say, 10% a year

If they say the investment is also low-risk, be extra wary.

There are some ridiculous examples out there. One Australian share trading program offered 890% a year. That means that if you invested $1 and waited 15 years, you would have six times the value of all the world’s goods and services produced in a year.

But more sophisticated scammers make it look less ridiculous. Bernie Madoff – the American who confessed in 2009 to running the largest financial fraud in US history – said he was giving investors a return of about 1% a month, with no losses for 20 years. You can’t get that high a return without ups and downs, but investors were ever hopeful.

Warning sign 2: Very high past returns

Scammers will tell you they’ve made huge returns. Sometimes they are just lying. Other times they have very carefully picked a particular period to present to you. You can be sure that over the long term, the story would be quite different.

Warning sign 3: Pressure to commit quickly

The salesperson will tell you there are only a few places left, or it’s cheaper if you enrol now. They know that if you go away and think about it, you might get talked out of it, or simply come to your senses. They will do anything to get you to make a quick decision.

Set yourself a rule to always say ‘No’ when pressured – or at least say you need a few days before you decide. This is easier said than done. You get a horrible feeling that you’re going to miss out and will deeply regret it. Believe me – you are much more likely to regret it if you commit on the spot.

There are many good investments out there that don’t require a quick decision. And arguably none that do.

Warning sign 4: A stranger approaches you – by phone, email, social media, snail mail, in a mall, wherever – with an irresistible offer, perhaps at ‘below value’

Through my columns, and at many seminars, I’ve asked if anyone has ever done well from an investment that began with the company approaching them. Nobody has ever said yes – although quite a few have said the opposite.

Always think about why someone is giving you this great opportunity to get rich. If it’s so good, why don’t they just keep it to themselves, and borrow as much as they can to invest? Could it be because, by selling you the investment, they are the ones getting rich?

Warning sign 5: Free or nearly free seminars.

Again, why are they doing this for you? A common tactic is to entice you along and then talk you into signing up for further expensive courses or financial advice or an investment. Once they’ve got you in the room, they can be pretty persuasive.

(By the way, just because someone charges for a seminar, that doesn’t necessarily mean it isn’t also a con. It must be wonderful for them, getting revenue for the seminar as well as making heaps later!)

Warning sign 6: A ‘black box’ you don’t fully understand – such as a computer program or app – that gives you high returns with low risk

I’ve been to a few seminars offering these. ‘All you have to do is pay up for the magic, and then trade shares (or options or bitcoin or whatever) according to what the black box tells you to do, and you’ll make much more money than you lose.’ They ‘prove’ it works by showing you some successful recent trades. They don’t, of course, show you the other unsuccessful ones. But it’s not that obvious. These folk are clever.

As we’ll discuss later, frequent trading of any investment is almost always a loser’s game. And no black box can change that.

Warning sign 7: Requests for PIN numbers, passwords or usernames

Sometimes these come in phone calls or emails supposedly from your bank or credit card provider or other legitimate business. But banks and the like never ask for that info. Keep it to yourself.

Warning sign 8: ‘You’ve won a prize’, but you didn’t enter

These come by snail mail or online. You’ve never heard of this outfit, but it’s still got a wonderful prize to give you. Funny, though, they always seem to end up asking you for money before they give you any – which you don’t ever receive.

Warning sign 9: A request to keep an investment opportunity private or secret

The people who make such requests do it in a way that makes you feel special and privileged. After all, not everyone gets the chance to share in a Nigerian official’s millions. Secrecy is a great way to keep you from checking with an accountant or lawyer.

The man who could pick shares perfectly

A conman selects ten shares.

He emails a million people, saying Share 1 will do very well, another million people, saying Share 2 will do very well etc.

Second round: He then targets the million whose share performed best. He selects another ten shares, and sends 100,000 people a recommendation on Share 11, and another 100,000 on Share 12 etc.

Third round: He targets the 100,000 whose second share also did well. He selects another ten shares, and sends 10,000 people a tip on Share 21, and sends another 10,000 a tip on Share 22 etc.

Can you see where this is going? By the next round, he has 1,000 people who are deeply impressed. After all, for them he has picked four shares that were big winners. Of course they are going to invest a lot with him . . .

False friends – taking comfort when you shouldn’t

Scammers have clever ways of making you feel everything is okay. Here are some of them:

• They run ads in reputable publications, TV or radio. You might trust the paper or whatever, but their advertising salespeople don’t have the time to check the credentials of advertisers.

• They use wording like: ‘It’s completely legal’, ‘Approved by [a government agency or Consumer NZ or similar].’ These are usually empty words. Note that the government and Consumer NZ don’t approve investments.

• They offer a money-back guarantee. But that’s useful only if the company still exists when you want to claim. Even if they do still exist, they tell you that you haven’t followed all the rules so the guarantee is not valid.

• They recommend that you check the investment with your lawyer or accountant – knowing that you’ll probably think, ‘If they say that, the investment must be solid, so I won’t bother.’ Do bother. And by the way, don’t ever use the lawyer or accountant they provide. Even if they are qualified, they’re hardly going to give you an unbiased view of an investment, with your interests at heart.

• They list impressive testimonials. But are the people real? And if they are, are they the promoters’ relatives and friends?

• They offer referrals from ‘independent’ offices or websites that aren’t independent. If they say a reputable company recommends them, check with that company. I know of cases where the company says they’ve never heard of the promoter or the investment.

• They use classy-looking literature printed on high-quality paper. Anyone can do that, especially if they’re making lots of money from fools.

• They guarantee that if you buy one of their units or apartments you will receive rent of at least $X for several years. The rent is high, and if it’s guaranteed, the investment must be good, right? After the guarantee period ends, you discover the rent the tenant is actually paying is much lower. The promoter has been subsidising the rent, using a small portion of the profits it made because you paid over the top for the property.

• They create websites and even fake government authorities to give the impression that they are legitimate. I’ve seen some pretty convincing ones. Mind you, not all fake websites are created by the bad guys. Check out www.howeycoins.com, which looks like it’s offering a wonderful ICO (initial coin offering) investment. But if you click on ‘Buy Coins Now!’ you land on the website of the US government’s Securities and Exchange Commission, with the following message: ‘If you responded to an investment offer like this, you could have been scammed – HoweyCoins are completely fake!’ It’s a great way of warning people.

• The nastiest of all – they befriend you, perhaps on a dating website. You correspond for some time, and may even have long phone conversations. You’ve found the love of your life, and will meet them in person soon, but they’re overseas. Suddenly they email to say they’re in a spot of bother, and could you possibly lend them some money, just for a short time. That’s the last you hear of them – except perhaps for a request for further money.

Another ‘false friend’ situation is when a real friend of yours, often a community or church leader, recommends an investment. It’s been great for them, but it’s a flop for you. Has your friend lied to you? Probably not.

This is what is sometimes called affinity fraud. The promoter approaches the community leader and offers them a really good deal. The promoter then puts in plenty of their own money to make sure the leader gets great returns. It’s an ‘investment’ by the promoter, who can then rip off all the people the leader brings into the scheme.

This is a particularly horrible scenario. It must make the leader feel terrible. And it invites the rest of us to not trust our friends. Let’s not let this stuff happen. Friends are great for many things, but not usually for hot investments.

How Bernie Madoff made off with smart people’s money

US psychology professor and author Robert Cialdini made some fascinating comments in America’s Wall Street Journal about Bernie Madoff and his hedge fund. In the following quote, I’ve put some phrases in italics, for emphasis.

The ‘murkiness’ of a hedge fund, said Cialdini, makes investors feel that it is ‘the inherent domain of people who know more than we do . . . This uncertainty leads us to look for social proof: evidence that other people we trust have already decided to invest. And by playing up how exclusive his funds were, Mr Madoff shifted investors’ fears from the risk that they might lose money to the risk they might lose out on making money.

‘If you did get invited in, then you were anointed a member of this particular club of “sophisticated investors”.’ Once someone you respect went out of his way to grant you access, says Professor Cialdini, it would seem almost an ‘insult’ to do any further investigation. ‘Mr. Madoff also was known to throw investors out of his funds for asking too many questions, so no one wanted to rock the boat.’

Other tips

1 The early bird gets the bucks

Affinity fraud isn’t the only situation where the first people in the investment do really well. In Ponzi schemes, the early investors think they’re getting high returns and tell others about the scheme. In fact, their ‘returns’ are partly or fully made up of the money later investors put in – after the promoters have creamed off their take. In the end, the music stops, and more recent investors get off the roundabout with little or nothing.

While Ponzi schemes are illegal, pyramid schemes aren’t necessarily. In pyramid schemes, early investors or purchasers are rewarded for recruiting others – we’ll call the new recruits the second tier. Then the second tier recruit more people to make up the third tier, and the first and second tiers are rewarded for that. Then the third tier recruits more people, and the first, second and third tiers are rewarded. And on and on it goes.

The top-tier people make a lot of money, and the second tier also does pretty well. But by the time you get down a few tiers, there’s not much to go around.

I don’t like the way these schemes work. I suggest you give a miss to any scheme in which you are expected to recruit others.

2 Trouble in your inbox

Surely everyone knows about this stuff by now. But apparently not. If something enticing comes in by email, look closely at the sender’s address. And if you’re redirected to a website, look closely at the actual URL to confirm it’s legitimate. Scammers often use names that look very like legitimate names. If you have any doubts, phone the organisation, using a phone number you got from somewhere other than the website. Better still, just give any email offer a miss.

3 Take care with your personal info

The 2018 scandal with Facebook has made everyone more wary about what personal information they put online. But still, we can let info slip without realising it – even in phone calls. Somebody might ‘innocently’ ask if you have a cat or a dog, and if so what’s its name. Or they say, ‘I think my mum went to school with your mum. What was her maiden name?’ And they’ve got part of your password!

You can be caught out, too, if you’ve been asleep. I heard of a man who was woken by a 6 am phone call. ‘I’m calling from Visa,’ said the voice. ‘Someone is using your credit card in Turkey. I just need you to verify your details.’ The drowsy man said too much before he had a chance to think about what he was doing.

4 Suspicious?

Do an internet search on the business name coupled with the words ‘scam’ or ‘review’. If you find damaging information on the company, obviously give it a miss. But if you find only good info, that doesn’t necessarily mean all is well.

Two websites you can rely on are run by Consumer Affairs and the Financial Markets Authority. On www.consumeraffairs.govt.nz, click on Scamwatch. This tells you, ‘How to recognise, avoid, and take action against scams, protect personal information, and prevent identity theft both online and offline.’ It has lots of readable and useful info, including ‘Report a scam’. Do!

On www.fma.govt.nz, do a search for ‘scams’. That will give you types of scams, how to avoid them, and info on specific named investments to avoid (but don’t be comforted if a company isn’t listed there).

Above all else . . .

Perhaps rule number one in the fight against scams is: Never invest in anything if you don’t fully understand where the returns come from.

We know that interest we earn on a term deposit comes from the bank rewarding us for having the use of our money for a while. We know that with property we will earn rental income and hopefully a gain when we sell. We know that with shares or a share fund we will earn dividends and, again, hopefully a gain when we sell. But what about, say, binary options – which were being sold by swindlers recently? How do they generate wealth?

With many scams, it’s not clear where the returns are coming from. That probably means they won’t actually come.

True tale: Not even the salesman understood

Some years ago a friend of a friend asked me to go with her to a free seminar about an ‘investment opportunity’. It was something to do with property, but it was complicated. I couldn’t understand where the promised high returns were coming from.

After the main guy presented his persuasive spiel, the audience was broken up into small groups, each with a salesperson to answer our questions and sign us up. I asked lots of questions, and I soon became convinced that the salesperson didn’t understand where the returns came from either. But he was clever at hiding it.

The others in my group soon became impatient with me. My irritating questions were probably planting doubts in their minds, putting stumbling blocks across their pathway to wealth. I soon gave up, but as I walked away – taking my friend with me – I saw several others in my group lining up to sign on the dotted line.

I don’t know how they did. The whole outfit seemed to disappear from the limelight soon after that. But it’s not hard to guess.

Looking back, I’m sure the whole scheme was deliberately confusing. Put lots of numbers on a whiteboard, move them around and spout lots of complicated financial words, and write ‘12%’ at the bottom. The suckers will sign up.

But not you!

Moral: If it’s unclear, give it a miss.

Step 5 check

Have you:

![]() Set a savings goal?

Set a savings goal?

![]() Paid yourself first?

Paid yourself first?

![]() Promised that you’ll save more whenever your costs or taxes fall, or you get a lump sum or pay rise?

Promised that you’ll save more whenever your costs or taxes fall, or you get a lump sum or pay rise?

![]() Worked out the best investment for your savings?

Worked out the best investment for your savings?

![]() Ventured offshore?

Ventured offshore?

![]() Thought hard before going into individual shares or a rental?

Thought hard before going into individual shares or a rental?

![]() Learnt how not to be scammed?

Learnt how not to be scammed?

Reward

Chocolates, cheese or flowers; or a ‘me day’ with a walk, book, time with family, being creative; or donating to a charity, or anything else that makes you smile.

What’s next? All this saving is great, but how do you deal with market ups and downs?