In which we . . .

• Learn how and why you should spread your money around . . .

• . . . And don’t look over your shoulder

• . . . And forget about timing the markets

• . . . And keep risk down so YOU choose when to sell

• . . . And – best of all – relax

• Look into our minds, and understand why we make bad investment decisions

• Discover how men’s and women’s investments differ

This book is about investing easily. That means not worrying about your money. ‘That’s all very well,’ you may be saying. ‘I don’t worry when everything’s going smoothly. But when every newspaper and news bulletin is screaming “‘Crash!”, and telling me how much the average person in KiwiSaver has lost, of course I’m going to fret. Wouldn’t you?’ At the risk of sounding smug, my reply is, ‘Nope!’

Even when the markets are misbehaving, if you follow the five rules in this step, you should also be able to stay cool.

Before we start, though, I should note that I’ve seen so-called experts challenging every one of these rules. Often they have a vested interest. They’ll make more money out of you if you trade frequently, for example. But still they can sound pretty credible.

So why listen to me? I first learnt these rules quite a few decades ago when I was studying for my MBA. I was working full time as a financial reporter for the Chicago Tribune, and after work, at about 5.30 pm on one or two nights a week, you could have seen me trudging along Michigan Avenue, textbooks under one arm, to the University of Chicago’s downtown Business School. Most of the university’s MBA students studied full time on campus. But I was one of a growing number who attended evening lectures, one or two courses at a time.

It wasn’t always easy to pay attention through lectures from 6 to 9 pm, with one coffee break, after a full day’s work. But the lectures I had no trouble staying awake through were those from a professor called Merton Miller.

Mert had made a deal with the university. He would teach an evening course only if someone would bring a cold beer into the lecture theatre for him partway through. Beer can in hand, he taught us finance, and clearly loved his subject. He knew many people in financial circles, and told lots of ‘war stories’ about how some academic theories didn’t work in practice, but the ones he taught us did work. That was confirmed in 1990, when Mert was awarded the Nobel Prize for economics.

Since I did the degree, the theories have been modified. But over the years that I’ve been a financial writer in the US, Australia and New Zealand, I’ve watched how the basic ideas work over and over again, in rising and falling markets. These aren’t just ideas for how things are now; they are ‘truths’ about money. Learn them and stick to them through thick and thin – especially thin – and you will come out ahead.

We’ve already talked about diversification a couple of times. Once was in Step 4: ‘Join the best KiwiSaver fund for you’, when we looked at investing not just in New Zealand but around the world. And the other time was in Step 5: ‘Boost your saving painlessly’, when I said that if you invest in rental property when you already own your home, that’s a worry because you’ve got heaps tied up in property. But diversification applies much more broadly than that – in fact to pretty much every aspect of investing.

Diversification has been called ‘the only free lunch’. Generally, in finance ‘there’s no such thing as a free lunch’. For example, you can’t get higher returns without taking higher risk. However, with diversification you can reduce risk without reducing your average return. How come?

Maths alert! Let’s say the average return on shares is 10%. (That’s rather high, but it keeps the maths easy.) If you invest in one company, the return might be anything from minus 50% to plus 70%. That averages out at 10% (halfway between minus 50 and plus 70).

But if you invest in many companies, some will do well while others will do badly, so their returns will tend to offset one another. The range of returns on the whole portfolio of shares might be minus 20% to plus 40%.

The average is still 10% (halfway between minus 20 and plus 40), but you’ve reduced the volatility of your returns. Sure, you miss out on the chance to get 70%, but you also miss out on minus 50%. Most people like that trade-off.

Main point: If you own lots of shares you won’t get the big highs or lows you can get with just one or two shares. You get a smoother ride.

Critics of diversification make comments like, ‘Why would you want to spread your risk over lots of investments, including some bad ones? Just find a few good ones and stick with them.’

Just?

Sticking with shares for the moment, I reckon it’s impossible to work out in advance which shares are good investments.

Why? Because it’s not about the quality of the company – which can quite easily be established – it’s about whether it’s underpriced, so you can make a good gain on it.

Prospects for a retirement village company might look great, with so many baby boomers retiring. But if everyone realises that and therefore pushes the share price up too far, the shares will be bad investments. Benjamin Graham, an American economist and author, has observed, ‘A great company is not a great investment if you pay too much for the stock.’

So how do you find underpriced shares? As I explained earlier (Step 4: ‘Join the best KiwiSaver fund for you’), if an expert is the first to realise a share price will rise, he or she will make money from that info, by buying fast. But their very purchase will push up the price. The demand for that share has risen. So those following on behind won’t profit from the price rise.

With lots of experts out there hoping to be first with the information, the chances that you, as a non-expert, will frequently pick which shares are going to rise fast is next to nil – unless you happen to know something juicy about the company where you or your neighbour works. But that’s ‘insider information’, and it’s illegal to trade on that. Don’t try! If you’re caught – and people do get caught – you will be in serious trouble.

In the absence of illegal insider info, you will still sometimes do well with your shares. Everyone is lucky sometimes. If you have several shares, some are bound to do well. Also, share markets trend upwards over time, so most shares rise.

But notice I said ‘several’ shares. That’s the point here. You can’t foresee which shares will zoom up, so diversify – hold lots of shares. Ten is good, 20 is better. As John Bogle, founder of huge index fund company Vanguard, puts it, ‘Don’t look for the needle in the haystack, just buy the haystack!’

The stock picking game

Earlier I mentioned that I taught a financial literacy course at the University of Auckland for five years, from 2009 to 2013. When I first planned the course, I realised that most of the students, fresh out of high school, wouldn’t know much about the share market. How could I give them an idea of what a share was? Out of that question was born the Stock Picking Game.

At the start of the course, I gave the students one-page summaries from a stockbroker about 25 New Zealand shares. Each student had to choose a share they thought would perform well over the 14 weeks of the course. I also assigned each student another share. Then I divided the 25 shares into five ‘portfolios’, or groups of shares, and each student was assigned to a portfolio.

So, at the beginning, each student had: their chosen share, my chosen share for them, and a portfolio of five shares. Then we set it all aside until the end of the course.

Before I go any further, many of you will be saying, ‘Hang on a minute. You’ve been telling us shares are a ten-year-plus investment. Now you’ve got students “investing” for 14 weeks!’ Good point – a point I made repeatedly to the students. And, if I’m honest, I would have preferred it if the NZ share market had fallen during those 14 weeks, to underline how risky short-term investing can be.

No such luck – except in 2010, when 16 out of the 25 shares lost value, even after including dividends. In the other four years, the average return (including dividends) ranged from 6% to 15% – very healthy returns for just three months.

Thank goodness in most years I could refer back to unhappy 2010! And in every year there were several shares that lost value, so that helped.

But on we went. There was lots else for the students to learn. Some of the lessons:

Most students were lousy stock pickers. In 2011, for example, the most popular share was Fletcher Building, probably because students expected it to benefit from the recent Christchurch earthquakes. But in the 14 weeks, its performance ranked 20th out of 25. And the second most popular, Air New Zealand, came dead last. Meanwhile, the top-performing share, NZX, which was chosen by just three students out of 400, produced an astonishing best return of 55% in just three months.

Then in 2013 the third to last share in popularity, Xero, came top with an even more astonishing return of 70%.

Of course, the quality of the student choices wasn’t always that bad. But most years the most popular shares tended to perform worse than the least popular ones.

Information affects share prices more or less immediately, and amateurs can’t benefit from it after that. The popularity of Fletcher Building – because of the earthquakes – illustrates that. By the time the students were picking their stock, in March 2011, the experts had long since calculated how much that company was likely to benefit from the quakes rebuild. That information had already pushed up the share price.

Don’t judge a share by its short-term return. Despite the fact that the students ‘invested’ for only three months, we also looked at longer-term performances of the shares. In 2011, for instance, while Fletcher Building and Air New Zealand did poorly over the three months, Air New Zealand had gained nearly 13% a year over the previous ten years. And Fletcher Building had averaged more than 20%. Their recent performances were far from typical.

A single share can be very volatile. NZX, top performer in both 2009 and 2011, came 22nd out of 25 in the year in between. Mainfreight, top in 2010, came dead last in 2013. And F&P Appliances, top in 2012, had come 20th out of 25 in 2010.

Perhaps most importantly – diversification smooths out the ride. When we looked at the portfolios of five shares, it showed how ‘owning’ more than a single share reduces the highs and lows.

In 2011, for example, the return on one share was minus 14% while on another it was plus 55%. But on the portfolios, the range was much smaller. The worst portfolio’s return was plus 1% while the best one got plus 22%. The same thing happened every other year, and of course it always will; the highs and lows are watered down.

Footnote: The students didn’t feel so bad about being lousy stock pickers after I told them about Lusha, the Russian circus chimp. Lusha was given the choice of 30 cubes, each with the name of a company on it. She chose eight.

A year later, her ‘portfolio’ – which included banks and mining companies – had grown a truly impressive three-fold. Lusha had done better than 94% of Russia’s investment funds, according to Moscow TV.

Other stories tell of people throwing darts at newspaper stock price tables, buying whatever stocks the darts land on, and beating most of the experts.

What about diversifying property?

The property market is more varied. While one Air New Zealand share is the same as another, every property is unique. That makes it harder for the market to be as ‘efficient’ – which means the price reflects the information everybody has. There will be property bargains out there.

Still, if you’re buying property as an investment rather than as a home, and you want to get those bargains, you will have to compete with people who buy and sell property for a living. They have become expert at spotting, for example, a house that can be cheaply tarted up for resale, or an office block in an area where demand for office space will grow.

I know more than one person who has felt confident they can pick bargain properties, only to be deeply disappointed. Again, it pays to diversify – which in the case of property means buying several or investing in a fund that owns lots of properties.

Managed funds

You really need, say, $100,000 to buy a wide range of shares or bonds. And to buy a range of properties, you need more. Most of us aren’t in a position to do that.

That’s where managed funds – in KiwiSaver and outside it – come into their own. As we looked at earlier (Step 4: ‘Join the best KiwiSaver fund for you’), the lower-risk funds hold mainly cash and bonds and the higher-risk ones hold mainly shares and property.

The point here is that they hold lots of different bonds or shares or properties, in various industries and locations. If some of a fund’s investments do badly, others do well.

Bank term deposits

Diversification applies here, too. If you have money to tie up for, say, three years, you might have the choice of:

• six-month term deposits paying 4%; or

• two-year term deposits paying 5%.

The two-year ones look better. But what if interest rates rise within the next year and you’re stuck with what now looks like a low rate? On the other hand, if you go with the six-month option and interest rates fall, you’ll be sorry you didn’t grab the 5% rate.

Nobody is particularly good at predicting interest rates. The answer is to put half your money in each. Looking back later, you’ll be glad that at least half your money was in the right place.

Owning lots of different types of assets

While it’s good to own many different shares or different properties or whatever, it also reduces your risk to invest in different types of assets. I’m not talking here about money you expect to spend in the next year or two or three. It’s best to keep that in bank term deposits. But beyond that, a mix is best. When one type of assets does badly another is likely to do well and compensate.

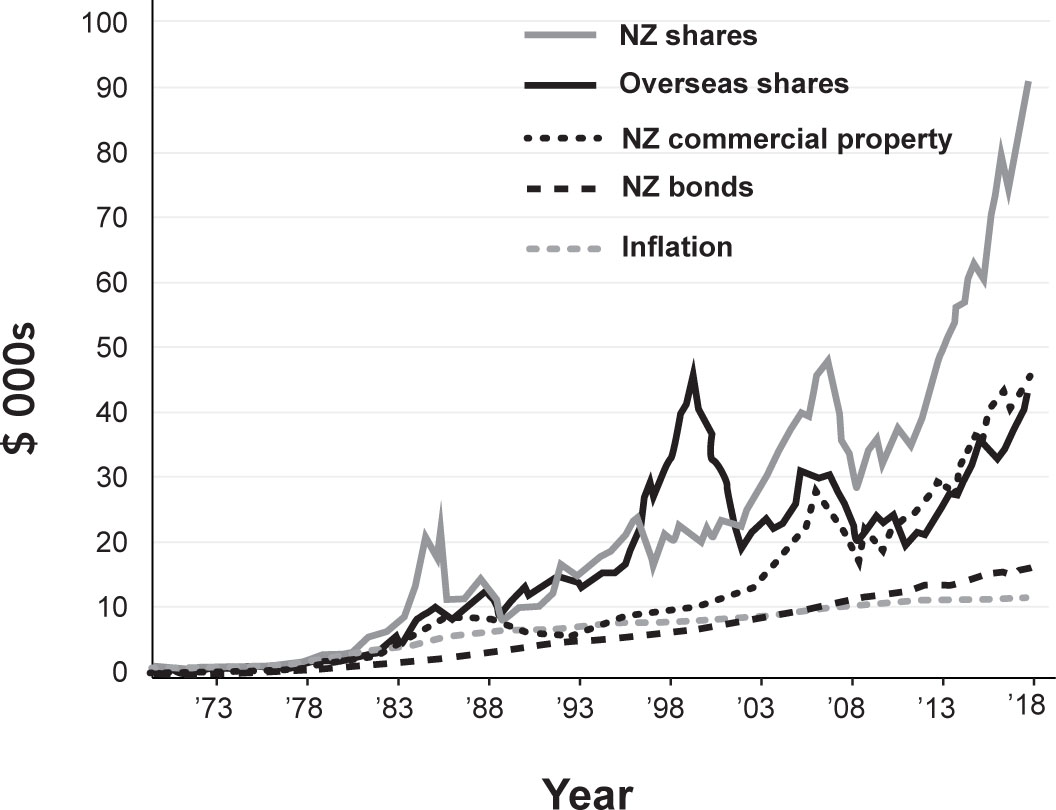

Figure 12: Different assets take different paths

Value of $1,000 invested in 1973 (after tax)

Source: MCA NZ

Technical stuff: This doesn’t include costs of investing, such as brokerage or fees. That would reduce returns quite a lot over a long period. On the other hand, this graph assumes you are taxed at the top PIR rate of 28% (income over $48,000). If you were on a lower income, returns would be higher because your tax would be lower. Shares include dividends and NZ shares include imputation credits. NZ commercial property includes rental income.

Shares include dividends, and NZ shares include imputation credits. NZ commercial property includes rental income.

Points to notice about Figure 12:

• The value of all assets rises over time. But there are periods when the rise of one would offset the fall of another – if you have invested in both.

• While you get a rougher ride in NZ and overseas shares, for most of the period they bring in the highest returns.

• NZ commercial property (office buildings, factories, shopping malls and so on) is also volatile, and it brings in higher returns than bonds. In recent years, property has also performed better than overseas shares, but for most of the period it didn’t. Who knows what the future holds?

• Bonds also have some fluctuations, although much less than shares and property. But their long-term returns are considerably lower. Your $1,000 has grown to: $91,000 in NZ shares; $46,000 in commercial property; $43,000 in overseas shares; and $17,000 in bonds.

• The more the fluctuations, the more the long-term growth.

True tale: Not such a good mix

In New Zealand’s version of the global financial crisis of 2007–08, finance companies were hit worst. Enticed by high interest rates, people had put large deposits with companies that made much riskier investments than they let on.

A financial regulator friend says: ‘We wanted to find out what people were doing investing in these things. It turned out they had gone to a financial planner, often an ex-insurance agent who had no idea. But the agents got trips around the world from the finance companies.

‘The planners thought that being in five or six finance companies was a diversified portfolio. They were really junk bonds. A good portfolio would have no more than 5% or 6% of those, and most would have none.

‘People were seduced by the interest rates they saw in the paper every day. In the global financial crisis they lost everything.’

Moral: Don’t put all your investments in one type of asset.

So how do you get a good spread of different types of assets?

To do this easily, turn to good old managed funds again. A balanced fund, for instance, typically holds several different types of assets.

Rule 2: Largely ignore past performance

Firstly, why did I say ‘largely’ in the heading? There are some things we can learn by looking at how investments have performed in the past. In the KiwiSaver step we noted that:

• A consistently bad investment is probably best avoided.

• Past performance, especially over many years, gives you an idea of the range of returns you might experience in the future.

But please don’t expect an investment that has done well – or badly – in the past year to continue to do well or badly. In sports and the arts, whoever did well last year is quite likely to do well again this year. But not in investing. Ads for investments quite often say something like ‘Past performance is not a guide to future performance’, but many people ignore that. Don’t!

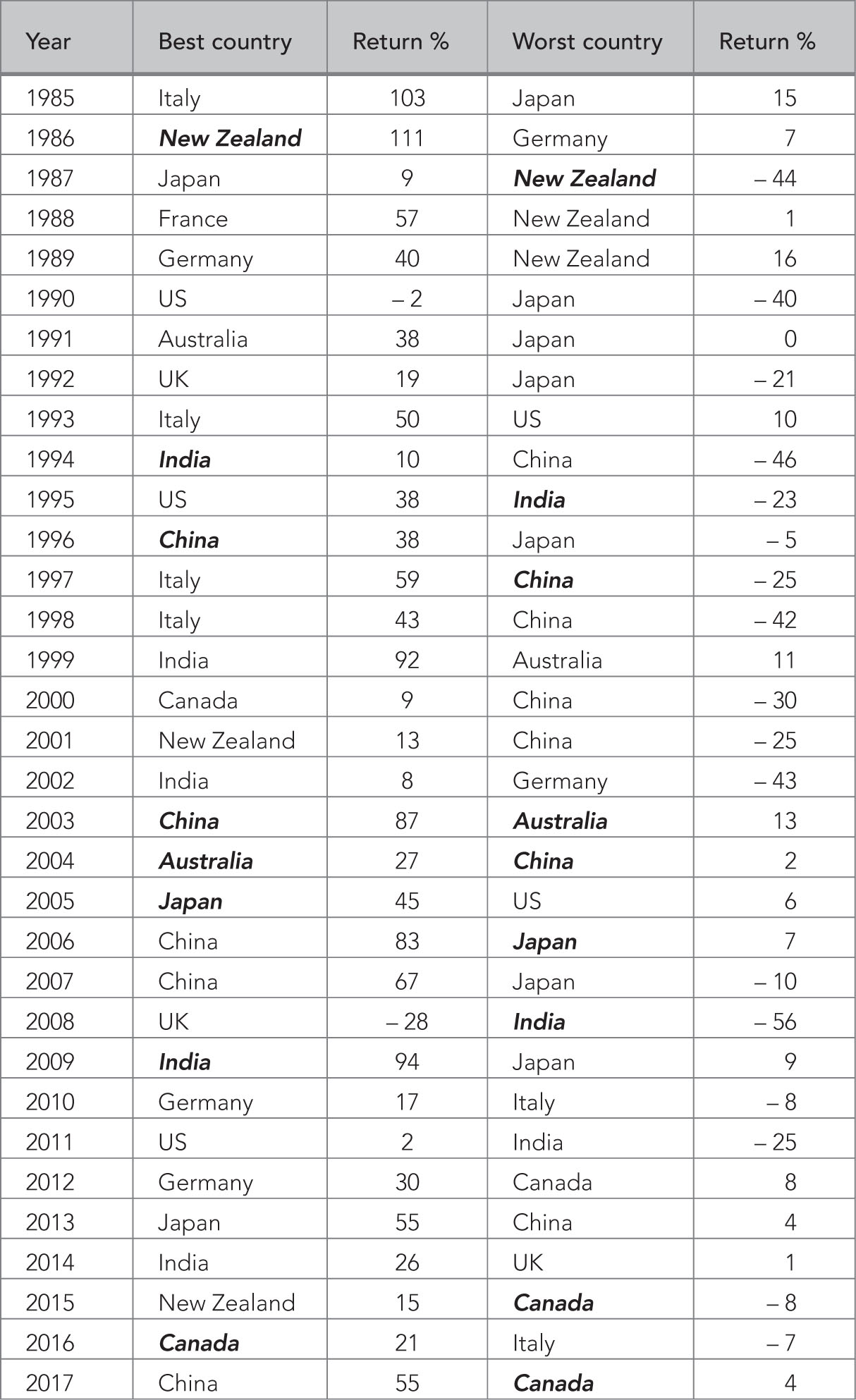

Figure 13 shows that returns on assets can change abruptly from year to year. Some points to note:

• Every type of asset, except cash, was best in at least one year and worst in at least one year.

• While sometimes there were runs – where the same asset was best or worst for two or three years – quite often an asset flipped from being best to worst, or vice versa, within a year or two.

• The highest returns were in property or shares – but so were the lowest returns. These are higher-risk investments.

• A return of 7% was the worst in 2005 but the best in 2010. Some years are just much better than others for all assets.

Clearly, past performance is rarely repeated, except in cash – and even in cash there was a huge change between 2008 and 2009.

Figure 13: Which asset did best – and worst?

Percentage returns on assets over 10 years. Numbers in underlined italics show the worst performing asset that year. Numbers in bold show the best performing asset that year.

Source: MCA NZ

The Economist magazine didn’t look at just 13 years – like our table – but the whole of last century. What, they asked, would happen to an investor who started out with $1 in 1900 and had perfect foresight? On every 1 January she moved her money into the type of asset that was going to perform best in the coming year. By the year 2000 she – or perhaps it would be her grandchild by then – would have $1,300,000,000,000,000. Extraordinary!

But of course she doesn’t have that foresight, so she settles instead for moving each January to the asset that did best in the previous year. What does she end up with in 2000? $290.

You get similar results if you look at which shares or managed funds performed best – or pretty much any other investment.

The fact that returns quite often swing from great to horrid, or back the other way, is no accident. In a share, for example, returns might soar as investors become excited and rush in. At some point, they start to realise some investors have overdone it, and the price can plunge quite suddenly.

Or the reverse. There’s been a share market crash. But a few days or weeks later, people start to realise that prices have simply dropped too far, and there are bargains to be had. If enough people think that, share prices can climb back surprisingly fast.

An interesting example of big swings back and forth can be found in the performance of different share markets around the world. For this exercise, I looked at the biggest markets plus Australia and New Zealand. The list is: Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, the UK and the US.

Figure 14 shows that back in 1985, Italy was the best performing market, with a return of 103%, which means share values more than doubled in a single year. Meanwhile, Japan did worst that year – with a highly respectable 15%. In the mid 1980s, share markets around the world were going nuts.

That continued into 1986, when New Zealand topped all the markets. Our 111% is the highest of any return in the table.

Figure 14: Every dog has its day

Different share markets’ performance over 33 years

Source: MCA NZ

But look what happened the following year. Our minus 44% is the second worst in the whole table. From a mighty height, the local market plummeted. And we were also worst for the next two years.

The numbers show that the New Zealand share market can be particularly volatile. All the more reason to have a fair chunk of your investments overseas.

Some other things to note about Figure 14:

• Firstly, can you spot why I’ve put some countries in bold? (To give you a minute to work it out, I’ll answer that in our fourth bullet point.)

• Almost every share market was the best performer at least once and the worst performer at least once.

• Some years are so much better than others for everyone. Take a look at 2008, the year of the global financial crisis. The best anyone could do was minus 28% in the UK, while Indian shares dropped 56%. That means that they more than halved.

• Why the italics? It’s when a country moved from either best one year to worst the next, or the opposite. It happened fairly often, when a share market simply dropped or rose too much, and returned to sanity the following year. Check out 2003 and 2004, when China and Australia swapped places. And what about Canada’s recent run!

• Just to confuse us, there are also periods when a market will do particularly well or badly for two or three years in a row.

What about share funds? Do the good performers stay good?

We looked at this earlier (Step 4: ‘Join the best KiwiSaver fund for you’), where we found that most active share funds (remember them – as opposed to index funds?) don’t keep performing well year after year.

Other research has much the same findings for all share funds, which is why I say ‘Go with the low-fee funds’. Returns change, but low fees tend to stay low.

Against the flow

The fact that top performers can later plunge, and bottom performers later soar, has led some investors to take an interest in what’s called contrarian investing – moving your money into what’s performed badly lately. There are even contrarian funds in the US and elsewhere that invest not only in whatever is unpopular in shares but also bonds, currencies, commodities, property and so on – anything where values move up and down.

Contrarian investors tend to do better than other frequent traders. But sometimes they land up in disastrous investments that are on their way to being worth zero. They get it wrong often enough that it’s better to just select the best long-term investments for you and hold them.

True tale: Quite contrary

A while back I received an interesting letter from a reader of my Weekend Herald Q&A column. ‘I think I need help!’ he wrote. ‘I’m not a negative kind of person at all, but every time the market drops for something, I am ready to buy.

‘I see bargains when share prices drop. I feel like I am getting a bargain, as if the share is on sale. Have I stumbled on the recipe for wealth or am I crazy? Note – I only use spare cash. I am not so crazy that I would do this with my retirement savings!’

This man – a good example of a contrarian investor – is miles ahead of most people. The common reaction to a market fall is to sell, not buy. But the market as a whole always recovers. Companies keep selling goods and services. Most of them make a profit most of the time, and their share prices reflect that.

So if you buy a range of shares when prices are low, you should do better than all the investors who buy only in rising markets. But it’s still not the best strategy. You’re still just guessing what markets will do.

Moral: If you must time markets, be contrarian. But, as I told this man, it’s better still to forget market timing and drip-feed, which leads us to our next rule.

Rule 3: Don’t try to time markets

‘Is now the time to buy?’ or ‘Should I be selling now?’ People often ask these questions after watching the share or property market rise or fall fast.

But by the time you’ve asked, it’s probably too late. The price has already moved. And it’s quite likely, in fact, that its next move will be in the opposite direction because the gain or drop was just too big.

Paul Samuelson, the first American to win the Nobel Prize in economics (and author of the economics textbook many of my generation used), once said, ‘The stock market has forecast nine of the last five recessions.’ In other words, downturns often seemed to be on the way, but they didn’t come.

And many stock market gurus, who became famous because they predicted a big rise or fall, have since wrecked their reputations. Morgan Stanley – a global financial services firm that would actually benefit from people moving their money in and out of markets – has commented on a study that tracked more than 4,500 forecasts by 28 self-described market timers, between 2000 and 2012. Only ten accurately predicted share returns more than half the time, ‘and none were able to predict accurately enough to outperform the market’.

Says Morgan Stanley: ‘As history has shown repeatedly, market timing is a losing game . . . Volumes of research critical of the practice have been written, and some of the greatest investment minds – William Sharpe, a Nobel laureate, Benjamin Graham, considered the father of value investing and John Bogle, founder of The Vanguard Group – have all counselled against it.’

Market timers often pull right out of share markets for a while – leaving after prices have plunged and coming back in after the market has risen. They take the falls and miss the rises. That can be a very expensive habit.

Let’s say you had $10,000 to invest in US shares at the end of 2001. If you had just left the money there, you would have had nearly $28,700 by the end of 2016 – a respectable average return of 7.3% a year.

But if you were in and out of the market and happened to miss:

• The best ten days – just ten days out of 15 years – your investment would have been worth $14,700. That’s just over half!

• The 20 best days, your $10,000 would have ended up as $9,600. Your investment went backwards.

All the action happens, it seems, in short spurts. Another long-term study found that there’s an average of just three days a year when nearly all the share growth occurs.

The above research is a bit silly in a way. Nobody would be that unlucky. Also, if you were out of the market a lot you’d probably also miss some of the worst days. But share markets trend upwards, so there are more good days than bad.

How to invest in up and down markets

The best and easiest way is to drip-feed your money in – the same amount every week or month – regardless of what markets are doing. Back in Step 5: ‘Boost your saving painlessly’, we talked about how this is difficult to do with property. But it’s easy with managed funds, including KiwiSaver.

Most people in KiwiSaver drip-feed into their account without even thinking about it. That includes all employees and others who have set up automatic payments into their account. You can do the same thing with many other managed funds, and it’s a great idea.

The magic of regular saving

If you’re making regular deposits of the same amount into any investment where the balance goes up and down – such as a KiwiSaver or non-KiwiSaver fund that includes shares, property or bonds – you’ll benefit from something called dollar cost averaging. It’s a confusing name – and in fact the whole concept is confusing for some people. If you can’t follow this, don’t worry. It works regardless of whether you know how it’s happening!

But let’s try to appreciate it.

When you invest in almost all funds, you buy what are called units. What follows also applies if you are buying individual shares, but we’ll use units in our example.

Maths alert! This is a ridiculously oversimplified example, to keep the maths easy to follow.

We’ll say you invest $1,200 a month into a fund.

For six months of the year, the units cost $12 each. So your $1,200 buys you 100 units a month. Over those six months, you’ve bought 6 x 100, which is 600 units.

In the other six months, units are only $8 each. With your $1,200 you buy 150 units a month. Over those six months, you’ve bought 6 x 150, which is 900 units.

Let’s review the facts:

• The average price over the year is $10 – halfway between $12 and $8.

• You’ve bought 600 plus 900 units – a total of 1,500 units.

• With the average price at $10, you would expect to have paid $10 x 1,500, or $15,000.

• In fact, though, you’ve paid $1,200 a month x 12 months, which comes to only $14,400!

• You’ve saved $600.

Main point: If the price goes up and down but you keep investing the same amount each month (or week), you end up getting bargains.

How did you get so lucky?

It’s quite simple really. You bought more units when they were cheaper, and fewer when they were more expensive. Furthermore, the more volatile the investment, the bigger the savings.

In some ways, then, a downturn is good news for regular contributors. It means you buy at cheap prices. You just need faith that the markets will rise again – and they will!

What if you have a lump sum to invest?

Perhaps you have an inheritance, or you’ve sold the bach or some other large asset?

Drip-feeding portions over time is still a good idea, so you don’t end up putting the lot into, say, a share fund, only to see the share market drop soon afterwards. That would be seriously discouraging. On the other hand, if you drip-feed for too long, the rest of the money is probably sitting in a bank term deposit in the meantime, earning a rather low return.

A good compromise is to do it monthly over a year. Or put a third in now, a third in after six months and a third in after 12 months.

It’s similar, actually, if you want to move some money from one country to another. Forecasting foreign exchange rates is just as fruitless as forecasting other market movements. So it works best to move it in a few chunks rather than all at once.

Resist temptation

Market timers tend to trade frequently. So do other people who simply like trading. There’s nothing inherently wrong with frequent trading, but you will nearly always end up worse off.

Your uncle might argue with that. He’s done really well by trading shares over the years. What he probably doesn’t realise is how much better he could have done.

One study looked at US investments between 1991 and 2010. The S&P500, an index that covers basically the biggest 500 US companies listed on the stock market, rose an average of 7.7% a year in that period – despite the global financial crisis in 2007–08. How did the average share fund investor do over that period? They got an average return of just 2.6%.

That makes a huge difference. If our investor had put $10,000 into an S&P500 index fund and left it there over the 20 years, it would have grown to $44,000. But if he or she had been a typical investor, it would have grown to just $16,700 – not much more than one-third of $44,000.

A more recent study, in 2017, found that over the previous 30 years, the S&P500 grew by 10.2% a year. But the average investor in share funds saw 4.0% growth.

Why do traders do worse? For one thing, impatience. The data ‘strongly suggests that investors lack the patience and long-term vision to stay invested in any one fund for much more than four years,’ says Lance Roberts, writing in the Wall Street Journal. ‘Jumping into and out of investments every few years is not a prudent strategy because investors are simply unable to correctly time when to make such moves.’

But also there are trading costs – brokerage, tax, commissions and legal fees. Tax? Well yes. New Zealand has a rather wobbly law about tax on investment gains. Many more people probably should be paying than do. However, that looks quite likely to change soon. Anyway, in the meantime, frequent traders are much more likely to end up actually paying the tax.

And over 20 or 30 years, if you pay 30% tax on your gains you’re likely to end up with about half of what you would have had if you had left the same money in an investment without trading. If you pay 33% tax, it’s even worse. Warren Buffett is happy sitting on the sidelines: ‘I never attempt to make money on the stock market. I buy on the assumption that they could close the market the next day and not reopen it for ten years.’

There’s not so much research on property, probably because every property is different. But the comments of Wellingtonian Mark Dunajtschik, 82 – former concentration camp prisoner and now property developer who in 2017 donated $50 million for a children’s hospital in Wellington – are interesting.

‘I am absolutely convinced that time is the hardest worker for property investment,’ he says. ‘Bob Jones said that . . . all property developers go broke and the only exception he knows is that bugger Mark Dunajtschik, and the reason he doesn’t go broke is because he keeps his property.’

Key message: Investing is one of the few human endeavours where doing less is better.

True tale: Amazing Grace

When Grace Groner, of the Chicago suburb of Lake Forest, died in 2010 at age 100, most people were astonished that her estate was worth $7 million.

‘She got her clothes from rummage sales,’ reported the Chicago Tribune. ‘She walked everywhere rather than buy a car. And her one-bedroom house in Lake Forest held little more than a few plain pieces of furniture, some mismatched dishes and a hulking TV set that appeared left over from the Johnson administration.’

Where had the money come from? ‘In 1935, she bought three $60 shares of specially issued Abbott stock and never sold them. The shares split many times over the next seven decades, and Groner reinvested the dividends,’ said the Tribune.

She left the money to a local college so that students could take up internships and study-abroad programs.

Moral: It’s often best to buy and hold shares, rather than trading. We should note, though, that Grace could have reduced her risk by buying shares in more than one company. She got lucky!

When you should move your money or sell

The basic rule is to make these moves because of things going on in your life, as opposed to things going on in the markets.

Some examples of when you should move or sell:

• When you get within a few years of spending the money – for example, if you’re in KiwiSaver you might be planning to buy a first home or spend the money in retirement. You don’t want to find that right before you take out your money the market has plunged. If you’ve gradually moved to a low-risk fund a couple of years earlier this won’t happen.

• If you’ve realised you’re in a riskier fund than you can cope with. But if you move for this reason, don’t switch back later!

• If you’ve realised you would prefer to take on more risk – knowing you’ll be okay with the ups and downs and you want higher long-term growth.

• The fund turns out to have high fees, or to offer poor customer service.

If you want to move to a different fund, but with the same provider – in or out of KiwiSaver – it should be easy and in most cases fee-free. Often you’ll be able to make the move online.

Rebalancing

Another reason to move money is rebalancing. Let’s say you’ve decided that the best mix for you is to have half your money in a balanced fund and the other half in a riskier share fund. Over time, though, they won’t stay half and half. One fund will grow more than the other, or in a downturn one will fall less than the other.

If you like the 50:50 split, you should review your investments, say, every three years.

An easy way to fix an imbalance is to make all new deposits into the fund that’s fallen behind. But if you’re not depositing much, or the imbalance has got bad, you may want to move some money from one fund to the other.

Don’t go all the way back to 50:50 though. Keep in mind that the next market move might take you there anyway. As long as you hover fairly close to 50:50, that’s fine. But if you don’t rebalance at all, your 50:50 split can get seriously out of whack over the years.

A financial adviser I know says his clients often baulk at rebalancing, which is hardly surprising. After all, they’re moving funds from a recently successful investment to a less successful one.

He finds it helps to remind them that they’re buying cheaply in the less successful investment. And in any case, it may turn out to be the better investment in future.

A reminder: Whether you’re moving money to rebalance or for another reason, if a large amount is involved it’s usually better to move it gradually. As we’ve said before, you don’t want to move all your money into a fund right before it plunges.

Rule 4: Never be forced to sell

There’s not a lot to say about this rule, but that doesn’t make it any less important.

We’ve talked earlier about how people who are forced to sell rental property may well find they have to sell right when house prices are low. The same thing can happen with shares or other investments – especially if you take high risks, or borrow to invest and therefore have to make interest payments.

It’s a really good idea to think through a worst case scenario before you take on a riskier investment. Include such events as losing your job or losing another source of income. How would you cope?

If you have lots of savings or family who could help you out in a crunch, that’s fine. But if not, take care. It’s when people are forced to sell that the horrible situations arise.

Remember – risky investments are for the long term. Don’t have the term cut short against your will.

The longer the term, the less the risk

Some US research shows how being in a higher-risk investment is much less risky over a long period. Investment service company Charles Schwab looked at returns on shares in the S&P500 index. It found that between 1926 and 2011 – a period that included really good and really bad times in the markets – the range of returns on shares narrowed markedly, depending on how long you held them.

• Over single years, the returns ranged from minus 43% to plus 54%.

• Over five-year periods, they ranged from minus 13% to plus 29%.

• Over ten-year periods, they ranged from minus 1% to plus 20%.

• Over 20-year periods, they ranged from plus 3% to plus 18%.

The longer you held the shares, the less dramatic the high returns, but also the less dramatic the low returns.

Over any ten-year period, the worst that happened was a 1% loss, and in the vast majority of the ten-year periods there was a healthy gain, ranging up to 20%. And there was never a loss over any 20-year period.

You’ve had enough rules by now: diversify, don’t chase returns, don’t time markets, don’t be forced to sell. And earlier on you were warned not to borrow too much. But here comes the easiest rule of all:

• Get yourself set up – which might simply mean getting into the right KiwiSaver fund for you, but might also include other investments.

• Test that you can cope with the bad times. If you’re in higher-risk investments – in or out of KiwiSaver – imagine how you would feel if your balance halved. If you would move to a lower-risk investment, do so now, rather than when the markets have plunged and you’re turning losses on paper into actual losses. But if you would stick it out, that’s great. A good diversified investment will always come right in time.

• Do little else. Sure, check every now and then whether you need to rebalance, or move money as you get closer to spending time. But that’s all. Economist Paul Samuelson has put it this way: ‘Investing should be more like watching paint dry or watching grass grow. if you want excitement, take $800 and go to Las Vegas.’

True tale: What not to do

A KiwiSaver provider tells me that a member of his scheme contacted him complaining because the return on his KiwiSaver account was minus 5% for the year ending 31 March 2017. I would have complained, too. That was a year when the markets were humming along nicely, so what’s with this loss?

The provider was equally puzzled, until he checked the man’s track record. It turns out he was a particularly diligent investor.

Every month he had looked at the returns on all of the provider’s KiwiSaver funds, and moved his money to the fund that had performed best in the previous month. He had done that 11 times in the year!

If he had stayed in his original balanced fund, his return would have been a highly respectable 9.2%.

Moral: Get into the right investments and leave them alone.

The psychology of investing

Why do so many people find it hard to keep their hands off their investments or make other wealth-destroying moves?

Lots of research has looked at how our emotions affect the ways we invest. The following are some of the little games we get up to – to our financial cost. If you’re aware of them, you can often overcome them, or at least make allowances for them.

Loss aversion

We have stronger negative feelings about loss than we have positive feelings about gain.

Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman, one of the first to write about how psychology affects investing, observed in his book ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’ that ‘Closely following daily [stock market] fluctuations is a losing proposition, because the pain of the frequent small losses exceeds the pleasure of the equally frequent small gains.’

Looking backwards

We become absorbed in how much we paid for something, possibly years ago. Often this means we won’t sell an investment simply because we refuse to sell at a loss.

What’s past is past. We need to ask ourselves if an investment is right for us now, and get rid of it if it’s not.

Herding

This is common – the tendency to do what other people are doing, whether it be buying or selling certain assets. Usually, by the time we take action, the good price has gone – if it ever was really a good investment in the first place.

Herding is comforting. If you lose and everyone else does, too, it doesn’t seem so bad. But a loss is still a loss. As we’ve observed, contrarian investors, who do the opposite of nearly everyone else, tend to do somewhat better than those following the mainstream.

Expecting the same market conditions to continue

This is particularly true if a market has been growing for several years. Investors forget the earlier down times, and think the good times will roll on forever. Or they think low mortgage interest rates will continue forever.

Sticking with the status quo

Our investments might no longer be suitable for us, but we don’t get around to changing them.

Let’s say your investments total $100,000. It’s a great idea to every now and then write down how you would invest that $100,000 if you were given it today. Then look into switching to those investments.

Responding to how something is presented

Which do you prefer: an investment that gains value nine years out of ten or an investment that loses value one year in ten? Think about it!

Letting a name mislead you

When a fund manager changed the name of a fund from ‘Junk Bonds’ to ‘High-Yield Bonds’ the investments didn’t change. They were high-risk and high-return. But a lot more people invested.

Emotional attachment

You inherited the shares from Grandpa, so you feel you have to stick with them. But would Grandpa really want you to do that, when you could be using the money in a much better way?

Being overwhelmed with information

These days, we don’t get too little info on potential investments, but too much. It’s hard to know what to take notice of.

That can lead to doing nothing. The stack of documents sits on your kitchen bench for weeks, until it becomes ‘just part of the furniture’. Can’t decide? Choose a couple of good investments, split your money between them, and get on with it.

Overconfidence

A little early success can be a dangerous thing. You buy a share and then its price zooms up, or you buy a rental property and then prices soar. It’s too easy to tell yourself you have the knack, and invest a whole lot more – only to see your luck turn against you.

True tale: On the bandwagon

A member of a wealthy New Zealand family came to his stockbroker in mid 1987, when the share market was in the midst of probably its maddest boom ever. He proudly showed the broker his portfolio of shares. They included about $20 million in the shares everyone else was in – Equiticorp, Chase, Judge Corp, Euronational and so on.

‘We were quite risk averse,’ says the broker. ‘We suggested he get out. But he ignored us. Each day the market was rising three or four per cent and he wanted to be part of it. On the day of the crash, he said, “You were right,” and gave us orders to sell.’

At least the shares were sold while they were still worth something. ‘Most of those companies didn’t exist six months or a year later,’ says the broker. ‘They’d gone.’ But still, the investor had lost heaps – as did many other share investors less able to weather that storm.

Moral: Don’t follow the crowds when you invest.

Vive la différence: how men and women invest

The first thing to say here is that there are many exceptions to the ‘rules’. However, I’m including this because it might draw your attention to weaknesses in the way you invest. Also, it’s interesting.

Let’s start with a couple of quizzes. The first is about gender and goal setting:

Which gender is more likely to achieve their goals if:

1. They set a specific rather than vague goal?

2. They told friends and family about it at the start?

3. They were encouraged not to give up if they lapsed – for example, they went on a chocolate binge when on a diet?

4. They focused on rewards associated with achieving the goal?

Answers in a minute.

Next we have a Colmar Brunton survey, in which they asked people: ‘Which of the following is most important to you when making an investment decision?’ There were strong gender biases in the answers to 2, 3 and 4. Can you guess them?

1. Being able to access money whenever you want.

2. Maintaining all the money originally invested.

3. Earning a reliable return – value of investment increases steadily.

4. Earning the best return overall – even if investment value changes over time.

5. Doubling your money in ten years.

Answers: On gender and goal setting, women are more likely to achieve their goals if they do 2 and 3, and men are more likely to succeed if they do 1 and 4, according to www.quirkology.com/UK.

In the survey, women were more likely to say 2, and men were more likely to say 3 or 4. (Men and women were about equally likely to say 1 or 5.)

Much other research has come up with two basic gender differences in investment style: men are more likely to prefer higher-risk investments; and men trade more.

We’ll look at risk first.

While higher-risk investing tends to bring in higher returns, sometimes men go for too much risk. Women, on the other hand, tend to take too little risk.

In an ANZ survey, people were asked, ‘Are you confident you’ll reach your retirement savings goal?’ About 55% of men said yes, but only 41% of women said yes. This is probably partly because women are more likely to take time out from paid work and are paid less, but it’s probably also because women are more likely to be in investments with lower returns.

Also, they might simply take less interest. Research by the Financial Markets Authority found young women ‘are the least engaged with their KiwiSaver materials and they are least likely to take action’ to get more out of KiwiSaver.

Conclusion: Women should think hard about whether they should increase their investment risk. And men should consider reducing their risk – by diversifying; using higher-risk investments only for the long haul; and keeping their borrowing low (men tend to have higher debt).

On trading frequency, research shows that women tend to buy and hold investments, while men are more likely to trade – usually to their detriment, as explained above.

An example of men’s counter-productive trading: a study of 2.7 million investors during the global financial crisis in 2007–08 found that men were much more likely than women to sell their shares at market lows.

Why do men trade more frequently? Studies have found that frequent traders tend to believe they are the exception; they will do well – although most of them don’t.

Should men be more confident with their money than women? Hard to say. Some research suggests men know more than women about finance, but other research finds they are about equal. Even if men do know more, they don’t know enough to trade successfully over time! It’s probably significant to note here that more compulsive gamblers are male than female.

What explains the gender differences?

If you read through the literature on this, a few ideas keep popping up. Women, some research shows, are more likely to seek financial help and advice. They’re more patient, and more likely to set goals. That could explain why they’re less likely to trade impulsively.

Men tend to be more competitive, and to see money as a way of keeping score.

If these differences ring true for you and your partner – regardless of who has which characteristics – it’s probably a good idea for you to make financial decisions together. Each of you can benefit from the other’s strengths, and counteract the other’s flaws! But if you can’t agree on a strategy, maybe you could each be in charge of 50% of your investments, so you have a range of risks and styles.

Who gets scammed?

There are gender patterns in scam victims.

Australian research on 80 telemarketing scams found that 90% of the victims were men.

And the Commission for Financial Capability says that UK research ‘found that older, wealthier, risk-taking men are the most likely targets for “share fraud”, when worthless or unsellable company shares are on offer. Women are more affected by “recovery fraud”, when scammers offer to recover funds or a lost investment in exchange for a fee.’

Interestingly, it adds, ‘The UK study demonstrated that the more financially sophisticated a person is, the more likely they are to be victimised, since fraudsters prey on investors’ overconfidence.’

Many people of both genders don’t like to tell others that they are victims. So scams are more widespread than we realise.

Step 6 check

Have you:

![]() Taken steps to spread your risk – over different assets and by holding lots of investments in each type of asset?

Taken steps to spread your risk – over different assets and by holding lots of investments in each type of asset?

![]() Stopped taking notice of which investments did best last year or last decade?

Stopped taking notice of which investments did best last year or last decade?

![]() Given up on market timing and trading, and instead set up regular investments?

Given up on market timing and trading, and instead set up regular investments?

![]() Made sure you won’t be forced to sell?

Made sure you won’t be forced to sell?

![]() Considered how psychology and gender might be hurting your investing?

Considered how psychology and gender might be hurting your investing?

Reward

Chocolates, cheese or flowers; or a ‘me day’ with a walk, book, time with family, being creative; or donating to a charity, or anything else that makes you smile.

What’s next? How will it be for you when your working days are over?