HEAD CONFIDENTLY TOWARDS RETIREMENT – AND THROUGH IT

In which we . . .

• Work out roughly how long you are likely to live (probably!)

• Take comfort about NZ Super

• Decide to SKI through retirement

• Set a retirement savings goal, panic, and then . . .

• . . . Look at many ways to make it easier

• Consider KiwiSaver and other investments in retirement

‘Retirement?’ you say (perhaps). ‘That’s many, many years away for me, and I’ve got so many other financial things to think about before then. I’m saving for retirement in KiwiSaver. That’s enough on that topic for me right now, thanks.’

If that’s you, that’s fine. I totally understand. I’ve been there – although it was some time back now! So if you want to skip this step and get back to it in ten or 20 years, it will keep. Still, it mightn’t be a bad idea to have a quick flick through, just to have an idea of where you might be heading when you get to your late forties or older.

Meanwhile, for everyone else – right up to centenarians and beyond – let’s look at how to set up your money for retirement in an easy-to-understand and easy-to-use way.

Some critics might say my way is too simple. But there will always be ‘ifs’ and ‘buts’ and ‘maybes’ in retirement planning, because nobody can predict future returns. So I see no point in being highly detailed.

Here’s a thought to help you on your way: Saving for your retirement doesn’t just make you happy when you’re retired. It also makes you more comfortable in the meantime, knowing you’re planning for the time when you’ll earn less money.

Firstly, let’s address perhaps the most important issue of all.

How long are you likely to live?

Of course nobody knows. You could die today. But barring accidents, we can get a rough idea of your life expectancy.

These days in New Zealand a man of 65 can expect to live – on average – until he’s 84. For a woman of 65 it’s until she’s 87. Note, though, that life expectancy keeps rising. So if you’re not yet in your sixties, the number might be several years higher by the time you get there.

In any case, those numbers are very rough. We all know many factors affect longevity. So, for a more accurate estimate of your own life expectancy at your current age, I suggest you go to the Lifespan Calculator at www.tinyurl.com/ExpectLife.

I really like this calculator. It considers all sorts of factors, such as your family history and driving record, and even whether you wear a car seatbelt. It also helps you to see how you could make changes that would increase your life expectancy. For example, if you increase how much you exercise, or eat better, reduce excess drinking, or stop smoking, you can see how each of those changes would affect your likely life span.

This calculator is American, so you have to give your height in feet and inches (which is probably not a problem for many of us older ones!). And your weight needs to be in pounds. If you know your weight only in kilograms, just Google ‘70 kilograms in pounds’ and it will convert it for you. The same goes for height – Google ‘170 cms in feet and inches’.

Just for fun, I filled out the calculator as if I were an 80-year-old woman who did everything right – starting out with being a woman, given that women live longer than men! Her life expectancy is 108. For a similarly saintly man of 80, it’s 104.

What to expect from NZ Super?

Earlier in this book I said, ‘I’m confident there’ll be reasonable NZ Super available for everyone in the decades to come.’ That’s not a common view. Younger people often say they expect the pension to be slashed, if not ended, by the time they get to retirement.

Many people in the financial world are happy about that expectation, and some even foster it. They point out that our population is ageing as the baby boomers reach retirement age and beyond. The number of people working to support the number of retirees is decreasing. ‘You’d better save heaps!’ they say. The more subtle message is: ‘Preferably in my products.’

Of course I’m not anti-saving. But it’s simply not true that NZ Super is likely to be cut way back.

NZ Super cost less than 5% of our gross domestic product before tax in 2017. The average for pensions in all countries in the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) is 9%. If we change nothing, NZ’s cost is expected to rise to 8.4% by 2060. While the experts want to get that down, no expert is calling for drastic measures.

A few years ago I did some work with Treasury on their ‘Long-term Fiscal Statement’. It sounds rather boring, but the idea is simple enough. Every few years Treasury looks at government spending and priorities over the next 40 years. And this of course includes the rising future costs of NZ Super.

It was interesting to see the different future scenarios the officials were considering. Currently, NZ Super is raised each 1 April to keep pace with rising average wages. In most years, wages rise faster than inflation, so NZ Super also grows faster than inflation.

What we could do instead, officials suggested, is link Super to inflation. That, plus gradually raising the age NZ Super starts from 65 to 67, would go a long way towards making ends meet in future.

A switch to inflation linkage would not be insignificant. While people living on just NZ Super could continue to afford the same treats and cheap ‘senior’ Tuesday afternoon movies, there would be a growing gap between them and working people.

Treasury officials were worried about that gap. Some were saying perhaps the annual adjustment to Super could be halfway between wage rises and inflation.

This is a million miles away from axing NZ Super altogether. And while none of us can predict what future governments will do, I believe it’s far more likely they will make fairly moderate changes.

One change that seems inevitable, though, is a rise in the starting age. Similar changes are already happening in many other countries, including Australia, Denmark, Germany and the UK and US.

In late 2016, the Commission for Financial Capability recommended raising the NZ Super age in three-month increments. The change, if it were adopted, would start in 2027. People who were 55 in late 2016 would get Super at 65 years and 3 months; 54-year-olds would get it at 65 years and 6 months; and so on, until 48-year-olds and younger would get it at 67.

In 2017, the National government proposed a more gradual change, which would affect people born after June 1972.

If a change along these lines occurs, I don’t think it will be a big deal. When the Super age rose a whole five years – from 60 to 65 – between 1992 and 2001, there wasn’t much outcry. And given that life expectancies keep rising, anyone who starts Super at 67 will probably end up getting at least as many years of payments as current retirees get.

If you’re worried about future changes to NZ Super, just remember that a growing chunk of voters will be retired. In 2018, about 20% of New Zealanders 18 and older are over 65. Fifty years later it’s expected to be 35%. What’s more, the elderly are more likely to vote. In the 2014 election, only 70% of people aged 18 to 24 went to the polls, but 94% of those aged 65 and over got out and voted. No government is going to trample on all those voters.

How much is NZ Super?

In 2018–19:

• Single people living alone get $463 a week before tax, or about $24,000 a year.

• A married couple, who both qualify, get $702 a week before tax, or about $36,500 a year.

In winter, from May through September, there’s also a tax-free winter energy payment. Single people with no dependent children get an extra $20 a week, and couples or people with dependent children get $32 a week. Anyone who says they don’t need that extra money can choose not to receive it.

NZ Super payments are made fortnightly. Apart from the winter energy payment, Super is taxed like other income.

Many older New Zealanders are largely dependent on NZ Super. In a 2017 report, ‘The Material Wellbeing of NZ Households’, Bryan Perry says of New Zealanders aged 65 and older: ‘40% of singles have virtually no other income source, 60% report less than $100 per week from non-government sources, and 75% have more than half their income from NZ Super.’

But couples over 65 are better off. ‘For example only 30% of couples report less than $100 per capita per week from non-government sources – but most couples are nevertheless still highly dependent on NZ Super, with 55% having more than half their income from NZ Super.’

I hope you won’t be one of those heavily dependent on Super. If you take the steps in this book, you shouldn’t be.

Tip: You can apply for NZ Super up to 12 weeks before your 65th birthday, and it’s a good idea to get in your application around then. It can take a little while to process, and if you turn 65 in the meantime you don’t get backdated money.

Setting a retirement savings goal

Before we get going, there are two important points:

• A retirement savings goal has got to be approximate – but I’ll help you make a reasonable estimate. It’s helpful to have something to aim at.

• The numbers in this section might look rather daunting. But don’t be discouraged. The next section is called ‘Making it easier’!

As you’ll see in our final step (Step ?: ‘Buy a home, or sell one’), we’re not automatically assuming in this book that you own a home or will ever own one. But if you decide to opt out of home ownership, you obviously need to retire with extra savings to cover the costs of your accommodation.

However, most people own their own home in retirement. The numbers: 83% of New Zealanders over 65 (excluding people in residential aged-care facilities) currently live in dwellings owned by them or their trust.

And a majority of younger New Zealanders will probably continue to buy houses and – hopefully – be mortgage-free by the time they stop working.

A 2018 BNZ survey found almost three-quarters of New Zealanders ‘are confident they will pay off their mortgage before they retire or semi-retire’. Others plan to use some of their KiwiSaver savings or other investments to make the last mortgage payments, or sell their home and buy a cheaper one.

If you’re a homeowner and none of those plans will work for you, you’ll need to add mortgage costs to your savings goal – or take some of the steps suggested in ‘Making it easier’.

Skiing through retirement

This is not about taking to the slopes. It’s SKI, which stands for Spend the Kids’ Inheritance!

People on lower incomes have, of course, always been unable to leave much of an inheritance. But a generation or two ago, better off people usually left something to their offspring, sometimes a hefty amount.

They would retire with a sum of money, and spend just the interest and dividends – or the rent earned on a rental property – but didn’t touch the initial sum, the capital. That was the inheritance, plus their home.

Most baby boomers, though, are thinking along different lines. Many will leave their home to their family, but plan to spend most of their savings during their retirement. And I expect the following generations will do the same.

There’s logic to SKIing. Families tend to be much smaller than a generation ago, with many boomers having one, two or three children. If they inherit their parents’ home, that’s a fair chunk each. Also, houses these days are worth more, relative to other assets, than they used to be.

Should you SKI? A test: Unless your adult children have special needs or have had a particularly bad run of luck, hopefully they will be doing okay financially. Tell them you plan to spend your savings but retain your home. If they object, that might be a sign that they are selfish and perhaps don’t deserve an inheritance anyway!

In the next part of this book, I’m assuming you plan to spend most of your retirement savings before you die.

A friend said to me recently, ‘Fly first-class or your kids will.’ It’s food for thought.

Let’s get on with goal setting

Look at your retirement savings goal as being made up of two components:

1. Money for regular spending

2. A lump sum

Your goal is the total of these two.

We’ll look at regular spending first. And the good news is that you’ll probably spend less in retirement than while you’re working. You’ll save by not having to pay:

• Work expenses: commuting, lunches, work clothes, dry cleaning, bought dinners and expensive pre-prepared food.

• Ideally, debt and mortgage repayments.

• Insurance. Around retirement time, or perhaps earlier, you may realise you no longer need life insurance. You can also stop insurance for loss of income. And other insurances, such as house and contents, are sometimes cheaper for older people. (But health insurance rises. More on that shortly.)

• The big one – saving. This may be taking a large chunk out of your income as you approach retirement. While some people keep saving until they die, retirement is really time to stop putting money away and start spending it.

I’ve been told off for adding another item to this list – the fact that you’ll have time to do more for yourself, rather than paying others for things like cleaning, lawnmowing and gardening.

‘That’s all very well,’ says a friend, ‘but as you get older you become less able to do things like maintenance. I have to pay others to do lots of things I used to do around the house.’

But he has an unusually big property. Many retired people move to smaller sections or apartments partly to escape having to do maintenance. You’ll have to judge how all this will apply in your circumstances.

Overall, though, retired people tend to spend less. And people in their eighties and older often say that their spending decreases further. That’s simply because, in most cases, they travel less and go out less.

There are, of course, some things that cost more in retirement. The big one is health insurance. Premiums rise at an alarming rate as you get older, reflecting how much more medical care the elderly tend to need. But as you might remember, I recommend you don’t drop health insurance despite the high premiums. For ideas on how you might keep premiums somewhat lower, refer back to ‘Keeping insurance costs down’ (page 50) in Step 3: ‘Set up insurance – and a rainy day fund’.

Some simple calculations

After taking all of this into account, how much are you likely to want for regular spending in retirement?

Realistically, many of us think more in terms of ‘How much will I be able to spend in retirement?’ Here are some easy ways to get an idea of that. We’ll start with a very simple calculation.

Rule of thumb 1: If you retire at 65 with X hundred thousand dollars, you can spend $X a week

For example, if your savings total $100,000, you can spend $100 a week above NZ Super. If you’ve saved $50,000, you can spend $50 a week, and if you’ve saved $500,000, you can spend $500 a week.

You’ll be spending returns earned on your savings, but also gradually eating into the savings themselves – SKIing. But all the while the remaining savings are growing, with compounding returns.

Under this formula, your savings will probably last as long as you do. But if you live into your late eighties or older, you probably won’t have a huge amount left over.

Want something a bit more sophisticated? Members of The Society of Actuaries – who are experts on money and statistics – have come up with some calculations about how far a retirement savings sum will go if you use up most or all of the money.

I’ve chosen two to look at here, which I’ve called Rules of Thumb 2 and 3. If you want to see two others, or read more about the assumptions made, go to www.tinyurl.com/RulesOfThumbNZ.

Rule of thumb 2: If you retire at 65, each year you can spend 6% of your savings at the start of retirement

If you save $100,000, you could spend $6,000 a year – or $115 a week, above NZ Super. With $50,000 it would be $3,000 a year or $58 a week, and with $500,000 it would be $30,000 a year or $577 a week.

If you invest your savings in a conservative fund – in or out of KiwiSaver – your money will almost certainly last until your mid eighties. And, depending on future returns, it may last until you’re 90 or even 100.

You might have noticed that Rule 2 is a bit more generous than Rule 1.

An important point to note about both rules: If you retire after age 65, you will be able to spend more per week. That brings us to a third rule, which works regardless of your retirement age.

Rule of thumb 3: Divide your money by the years you want it to last

Say you retire at 70 and you want your money to last until you’re 90 – after which, NZ Super should be enough.

In the first year, spend 1/20 of your savings, in the second year 1/19, and so on. In the second-to-last year you’ll spend half of what’s left of your savings, and in the final year you’ll blow the lot and switch to NZ Super only – although of course you could choose instead to spread out your spending at that stage.

Unlike Rules 1 and 2, you won’t know in advance exactly how much you can spend each week. That will vary a bit depending on the returns you earn on your savings in the meantime. But, also unlike the other two rules, you do know exactly how long your savings will last.

What about inflation?

How does inflation affect the rules? Good question.

Under Rules 1 and 2, you’ll withdraw the same amount each year, but inflation will gradually decrease how much you can buy with that withdrawal.

But, as noted above, NZ Super – your other source of income – currently rises by more than inflation, and it seems unlikely it will rise by less than inflation in future. In any case, spending often decreases as people get older.

Rule 3 is much more inflation-proof. Because your savings will usually grow over the years, you will generally have more to spend each year.

I say ‘usually’ because if you have some of your savings in riskier investments – perhaps the savings you don’t expect to spend for at least ten years – and the markets fall, you will have less to spend in the following year. More about how to invest your savings in retirement shortly.

Which rule of thumb should you use? It depends partly on the inflation issue, which favours Rule 3 if you want to spend more each year. But Rules 1 and 2 give you more certainty about your spending amount.

Given that you spend a bit less under Rule 1 than Rule 2, you’re more likely to leave an inheritance (apart from your home), but you have a bit less fun along the way.

By now I hope you’ve got an idea of how much you would like to have for regular spending at the start of your retirement.

What about unexpected spending – such as a new roof, a better car, big medical bills, or happier things like a world trip? Many people like to start retirement with a good car and their home in good shape, but if you live into your nineties you might need another new car and new roof.

You’ll want a lump sum to cover all these things, and only you can decide how much that should be. For some, $50,000 will do; for others, it might be half a million dollars.

Your retirement savings goal, then, is your total for regular spending plus your lump sum. Does it look out of reach? Read on. But first, a brightener.

The best is yet to come

The market research firm UMR has done surveys on what makes New Zealanders happy. Some of their findings bring good news for older Kiwis. They include:

• The happiest age group is those aged 75 and over, followed by those in their late sixties.

• The happiest occupation is ‘retired’, with around 37% of retirees scoring themselves 9 out of 10 or 10 out of 10 for happiness. (By the way, homemaker was the next happiest group, followed by professionals and managers.)

• When UMR looked at marital status, widows and widowers – whose spouses had died and they hadn’t remarried – were happier than married, de facto, divorced or never married people. About 29% of widowers and 35% of widows gave themselves high happiness scores.

There’ll be more on this research in the last section of the book.

There are lots of ways you can make retirement easier financially. One obvious way is to retire later. As we’ve already discussed, younger readers are likely to find that NZ Super will start at an older age than 65. But many people are already retiring later than that age anyway.

This is no doubt partly because people in their mid sixties tend to be healthier than a generation ago, and they expect to live longer.

Workforce participation – part-time and full-time – for people aged 65 and over has soared in the past 30 years or so. According to Stats NZ, from 1990 to 2018, the percentage of people aged 65 to 69 in work more than quadrupled, from 10.2% to 44.5%; and the percentage of people aged 70 and over in work more than tripled, from 4.4% to 13.6%.

And the numbers, and percentages, of older workers are expected to keep rising. Working in your late sixties may become the norm.

Continuing to work has strong appeal for some people, the opposite for others. In a 2018 survey of people over 65, BNZ found two-thirds want to keep working because of the ‘value and satisfaction it brings’ or the ability to use their skills and talents. And more than half want to work for the social contact. However, close to a third said they need to work to get the money to pay their bills.

Whether you want to keep working or have to keep working as you get older, there are two pluses to doing so. For every year you keep working:

• You can save for one more year.

• You have one less year of retirement to fund with your savings.

Because of this double-barrelled effect, continuing to work past the usual retirement age can make a surprisingly big difference to how much you need to save for retirement.

How much? I worked through an example for a 50-year-old regular saver on an online retirement savings calculator. The relative spending numbers are what matter. I found:

• If that person retires at 65 they could spend $610 a week from their savings.

• If they retire at 67 it would be $730 a week.

• And if they work until 70 it would be $970 a week. That’s more than one and a half times the amount at age 65.

‘That’s all very well,’ you might be saying. ‘But I’m not sure I’ll be able to keep my job as I get older.’

There’s no doubt that some employers discriminate on the basis of age. But you don’t have to keep the same job, or even the same type of work.

What are you good at or love doing? Turn what was an interest into a part-time job. I’ve known people to make good money consulting, tutoring or teaching their hobby. How about setting yourself up as a cake decorator or home handyman? One former chief executive of a large company thoroughly enjoys mowing lawns in his suburb, and chatting with the residents in the process.

Following are some other ways to make it easier to reach your retirement savings goal.

Move house

This idea can be a trap for old players. I’ve known people who have planned to free up several hundred thousand dollars by moving from their three- or four-bedroom suburban home to a much smaller place, only to find they didn’t free up much at all.

The trouble is they wanted the new place to be low maintenance, perhaps close to bus routes, shops and health services, and with easy access. That’s what lots of baby boomers want, so those places are not cheap.

Having said that, many people do, in fact, free up sums as large as half a million dollars or more by moving house – especially if they move out of a big city. You might protest that you want to stay close to family and friends. But with the willingness to jump in the car or take a train or bus – perhaps with SuperGold card in hand – you may be able to get around that.

If you plan to move towns, do take the time to get to know the destination town well, though. You don’t want to get there and miss the restaurants, entertainment and bright lights. Perhaps rent out your big city home for six months or a year and rent in the small town on a trial basis.

Eat your house

It’s common for retired people to be asset-rich and cash-poor. They own a home worth a small fortune, but are buying cheap peanut butter. If moving to a lower-priced home isn’t a good option for you, there are other ways to make use of the value in your home.

Boarders or flatmates

Some people would rather struggle financially than take a stranger into their home. But I’ve known retired people to change their minds when they tried it, enjoying the company and the added security.

One friend who took in foreign students found it not only gave her extra income but also a much more diverse menu when the students taught her their ways of cooking.

Alternatives are to sublet a portion of your home – perhaps one wing or the downstairs – or to take in short-term ‘company’ through Airbnb, bookabach or similar schemes.

Note, though, that if you have others paying to stay in your home, you should tell your insurance company. While that might mean higher premiums, you want to be sure to have cover if, for example, the people staying with you get sticky fingers. You should also check your tax situation. See www.tinyurl.com/NZBoarderFlatmate.

True tale: Up in the air

‘My sister has a prime waterfront spot,’ says a reader of my Weekend Herald column, ‘and she converted their downstairs into rental accommodation for Airbnb, and it has just taken off. They are earning more for their small two-room complex than my husband earns a week. People are in and out on a daily basis, and there are very few overheads, especially as she charges a cleaning fee. ‘A great way to increase your retirement income,’ she says. ‘Who needs to save?’

My comments: With talk of bed taxes – and with some cities, including Auckland, charging higher rates for people who rent out part or all of their home on a short-term basis, and other cities considering similar action – this option probably won’t remain as lucrative as it is now. Also, as more people get in on the act, competition will push down prices. You hear, too, of neighbours not welcoming the comings and goings, and that should be taken into account.

But still, this can be a good way to boost retirement income – if you don’t mind sacrificing some privacy. And maybe that won’t be an issue, depending on the layout of your home.

Moral: There’s gold in that thar home.

Subdivide

Many suburban properties are large enough to fit a second house on them – in some cases after the original house is moved a few metres. And some retired people would welcome the reduction in the size of their garden, and perhaps the security of having somebody else living nearby.

Don’t dismiss the idea because you looked into it some years ago and found you weren’t allowed to do it. In many bigger cities, zoning rules have changed and subdivision is now encouraged.

Rates rebate or postponement

Don’t skip this, thinking you’re not eligible. While rates rebates are for people on low incomes, including retirees, rates postponement varies. In some areas you have to be struggling, in others it’s open to everyone.

Hardly anyone uses rates postponement, and that’s a pity. It’s a great way to free up perhaps several thousand dollars a year that could be spent on bills – or fun. I recommend you look into it in your retirement.

With rates postponement, you delay paying part or all of your rates until you sell the property or die. Basically, the council lends you the money in the meantime. And when the house is sold, the council gets its money back.

You pay relatively small upfront costs and possibly an ongoing fee, as well as fairly low interest. In Auckland, for example, the interest rate is the council’s cost of borrowing, which will usually be well below mortgage rates.

The interest compounds over the years, but generally this is not a big deal. While your loan is growing, the value of your house will be growing faster in dollar terms. Sure, house prices might fall for a while, but over the long term they increase.

In any case, if you start worrying about the size of your loan you can always stop rates postponement from then on, which will slow the growth of the loan.

Different councils’ policies vary. In most cases, you can pay back the rates plus interest, with no penalty, at any time if your circumstances change. You might, for example, inherit some money, and would like the interest clock to stop ticking.

For more info, go to www.tinyurl.com/NZPostponeRates. For Aucklanders, see www.tinyurl.com/AuckRatesPostponement.

A rates rebate is different. It’s only for those on low incomes, and you don’t have to repay the money. Rates rebates are run by local councils but paid for by central government. Your rates can be cut by up to $620 a year.

According to the Department of Internal Affairs website: ‘How much you can claim depends on:

• how much your rates are — this includes local, regional and water rates

• your income, and

• whether you have any dependants, such as children, living with you.

‘If your gross (before tax) income is $24,790 (about the same as NZ Super for a single living alone) or less you can often claim the full amount. If your income is higher you may still be able to get all or part of the rebate depending on:

• how much your rates are, and

• how many children or other dependants are in your household.’

In 2018 the rules were changed so that retirement village residents who don’t own their unit, but pay fees to live there, can also claim a rates rebate.

For more info, see www.tinyurl.com/nzRatesRebate. For Aucklanders, there’s more info at www.tinyurl.com/AuckRatesRebate.

Reverse mortgage

This is rates postponement on steroids. You borrow money, often from a bank, in an arrangement similar to an ordinary mortgage, but you generally make no repayments until you sell the property or die.

The important differences from rates postponement are:

• The interest rate will almost always be considerably higher.

• You can borrow much more than the amount of your rates.

For these two reasons, the loan can grow big – frighteningly big for some people. But keep reading. In the right circumstances, reverse mortgages can be a great idea. I’m thinking of getting one myself in my very old age. Basically, I plan to spend my savings until I’m 90, and then live on NZ Super and a reverse mortgage – for the next 20 years or so!

Over the years, several different banks have offered reverse mortgages for a time, and then stopped. I don’t think there’s been a huge uptake. But also some bankers have said the fact that they charge fairly high interest can lead to negative feelings about the bank.

The interest rate – perhaps a couple of percentage points above ordinary mortgages – is probably justified though. For one thing, these mortgages are somewhat riskier for banks because they grow bigger over time, and the banks don’t know when they’ll be repaid. For another, the banks say they need to spend a lot of time explaining the product to people. One bank used to hold three meetings with customers before signing them up, in an effort to make sure they understood what they were doing.

I’m sure all providers would also insist you discussed a reverse mortgage with a lawyer.

Usually, you can borrow only quite a small portion of your equity (the value of the property minus any mortgage you have). The amount you can borrow increases as you get older – because there’s less time for the loan to grow.

The lender will want to protect their equity. That means you’ve got to keep the house fully insured, pay your rates, and maintain the property. But you would probably do that anyway.

Because a reverse mortgage can grow big over the years, I don’t recommend getting one in your sixties or early seventies – unless you’re in poor health. But consider it for later in retirement.

You might find there are only one or two providers offering them. Talk to your own bank, too. Even though most banks don’t announce it, some will set one up for a customer.

If you have adult children, it’s a good idea to discuss what’s happening with them. If they are expecting to inherit your home, they otherwise might get a rude shock when they find a bank owns half or more of it. But don’t skip a reverse mortgage just because of the kids. Remember, we’re SKIing!

Questions to ask about reverse mortgages:

• Will you have the right to live in the property for life, no matter how long you live?

• What happens if you move to another property, or go into care for what is intended to be a temporary period but it drags on?

• Is there a guarantee you won’t owe more than the proceeds from selling your property? You will usually get this important guarantee, but you should check.

• How will the loan affect your estate when you die?

• Can you set aside part of your equity in the property (house value minus mortgage), so that there’s something left for the kids or nieces and nephews to inherit? This will mean you can borrow less.

If you decide to get a reverse mortgage, try to get a flexible one, and borrow only as much as you want or need at the time, adding more later. Don’t get extra money that will sit in a bank account earning much less interest than you are paying on the loan. That’s dumb! If you keep the loan amount low for as long as possible, there’s less interest to compound.

I suggest you also do a Google search on reverse mortgages. You will probably come up with the latest Consumer NZ article on the topic. Read it. As I’ve said before, if you’re not a member of Consumer NZ and so can’t get access to the article, join!

Examples of a reverse mortgage

Heartland Bank, which offers reverse mortgages, has some handy calculators at www.seniorsfinance.co.nz.

They show, for example, that if you’re 65 and your house is worth $600,000, you can borrow up to $120,000. If you’re 75 you can borrow $180,000, and if you’re 85 it’s $240,000.

Double those amounts if your house is worth twice as much. For example, at 65 with a house worth $1.2 million, you can borrow $240,000. At 75 it’s $360,000 and at 85 it’s $480,000.

Let’s look further at the situation if you’re 75, and your house is worth $600,000. You decide to borrow $50,000, and the bank charges you 7.82% (compared with its floating rate at the time of writing of 5.85%).

The bank assumes house values rise by a fairly conservative 3% a year.

• By 80, the loan will total $74,000 and your house value will be $696,000.

• By 85, the loan will total $109,000 and your house value will be $806,000.

• By 90, the loan will total $161,000 and your house value will be $935,000.

• By 95, the loan will total $238,000 and your house value will be $1,084,000.

Your loan more than triples while the house value less than doubles – because the loan is growing at a faster pace. But the gap between the two numbers keeps increasing. You’re fine. If you die or move out at 95, you or your heirs will get $1,084,000 minus $238,000, which is $846,000.

Maths alert! However, if you borrowed the maximum you’re allowed at 75 – $180,000 – the loan would grow to $856,000 by the time you were 95. Meanwhile, your house would be worth the same $1,084,000 as above.

With this higher loan amount, the gap between the two numbers decreases over time. If you lived well past 100, the gap would disappear. But there’s no need to panic: as of October 2018 the Heartland Bank offers a No Negative Equity Guarantee, which means, it says, ‘that you will not have to pay us back more than the net sale proceeds of the property, even if this amount is less than the outstanding loan balance’.

Main point: If you borrow a larger amount, the gap between the loan and your house value may decrease.

Don’t forget, though, that the bank is assuming house prices will rise by 3% a year. They may well rise faster.

Play around with the calculator, to get a feel for how the numbers might work for you.

Sell your house and become a tenant in another house

Most homeowners would dismiss this idea outright. They have owned their own home, with the freedom to do what they want and the knowledge that no landlord can kick them out. Who would want to lose that?

But some might be happy to trade those advantages for not having to worry about maintenance and so on – being able to just call the landlord when things go wrong.

And financially they could be onto a big winner. The proceeds from selling some houses these days could buy you many years of rent plus some wonderful trips and a luxurious lifestyle.

It’s not a silly idea, especially if you could get a long-term lease. There are probably plenty of landlords who would love to have a retired person as a long-term tenant.

Sell assets

Are you using the bach or the second car or the boat less and less as you get older? Consider turning them into cash. And then there’s the smaller stuff. Selling is so much easier these days, using the internet. If you’re not familiar with how Trade Me works, learn. It’s fun. And you’ll be surprised at how much some of the junk sitting around your place will sell for.

Take the time to clean up the items and take appealing photos of them. Other photos on Trade Me might give you some ideas about how to ‘pose’ your items.

Consider, too, selling some of your valuables. I’m not suggesting you part with the paintings or ornaments or jewellery you love. But we all have some items we’ve fallen out of love with, or maybe never really liked, if we’re honest. Sell a few pieces and fund a holiday. Why not?

A bonus of selling things is that you free up space and simplify your life. And let’s be honest here – whoever ends up going through your stuff after you’ve passed on to the Place Where Money Doesn’t Matter will be very glad they have less to go through.

A word of warning: you don’t want to sell something only to find that one of your heirs particularly loved it. So perhaps talk to them first. It’s a good idea to have that conversation anyway. You can then be sure you leave the right things to the right people.

What if I live to be very old?

As we’ve already discussed, old old people don’t tend to spend much, and many say they find NZ Super is plenty. And rates postponement or a reverse mortgage can work well at this stage, with not many years of compounding interest.

But if you’re still worried, here’s a trick. Leave some money in your will for charity. If you live past 90, you become the charity! At that stage, change the will and spend the money.

One – very important – way to make your savings go further is to take more risk in the run-up and during retirement. As you must know by now, this will give you higher returns, on average over time. The tricky part is that in retirement you are planning to spend your savings, no longer locking the money away.

However, unless you retire at an unusually old age, or you’re in poor health, you will probably start retirement expecting to live for 15, 20 or 30 more years. So you don’t need to do what many people do at retirement – putting all their savings in conservative investments like bank term deposits.

Definitely do that with the money you plan to spend in the next three years or so. But if you’re wise you’ll put:

• the three-to-ten-year money in bonds or a balanced fund – in or out of KiwiSaver;

• the money for ten years plus in a KiwiSaver or non-KiwiSaver share fund or similar.

Every year, move some money from the share fund to the balanced fund or bonds, and some from there to term deposits, so you keep to the three-year and ten-year cut-offs.

This will mean your savings are more volatile. But by now I hope you’re feeling braver about that.

In our Rule of Thumb 2 earlier in this chapter, the Society of Actuaries assumed your savings earned 3.5% a year on average, after tax, throughout retirement. But if you use the plan above, you’ll probably earn a higher average return. That means you can spend a bit more or leave more to your heirs.

Apart from keeping some retirement savings in riskier investments, follow all the same rules concerning investing that we’ve already talked about – diversify, largely ignore past performance, don’t try to time markets, and don’t trade frequently. Just because you’ve retired doesn’t mean any of that changes.

KiwiSaver in retirement

KiwiSaver can have a big role in your retirement. Once you get to 65, you can withdraw your KiwiSaver money whenever you want to – unless you’ve been in the scheme for less than five years, in which case you must wait until the five years are up. (If proposed changes go ahead, the five-year lock-in will no longer apply to people who join after 1 July 2019, but will continue to apply to people who joined before that date.)

When you get access to the money, your tax credits stop. If you’re still working, your employer is allowed to also stop contributions, although many don’t. If your employer keeps contributing, that’s an extra reason to stay in the scheme.

But in any case, stay in. Even if you want to empty your account to pay off a mortgage, for example, keep at least a few dollars there. Once you’ve closed the account, if you’re 65 or over you can’t open it again. (Under the proposed changes, though, anyone will be able to join KiwiSaver at any age.) And KiwiSaver can work well in retirement for medium- and long-term money.

Just one note of caution. People often comment that their KiwiSaver account is bringing in higher returns than a bank term deposit, so they use it for their short-term savings in retirement.

That’s a worry. Unless you’re in a very low-risk defensive fund – in which case your returns may not be higher than bank term deposits anyway – your KiwiSaver account will have some volatility. That’s not a good idea for money you’re about to spend.

Laddering

This is a good way to set up your term deposits or bonds. You can do this at any time in your life, but it tends to be more useful in retirement because you’re spending rather than saving, so you’re likely to have more money in term deposits and bonds then.

Let’s say you want to hold your money in two-year term deposits because, in most circumstances, you’ll get higher interest than if you went for a shorter term.

Divide your money into, say, four lots. So if you’ve got $100,000 to invest, put:

• $25,000 in a six-month deposit;

• $25,000 in a one-year deposit;

• $25,000 in an 18-month deposit;

• $25,000 in a two-year deposit.

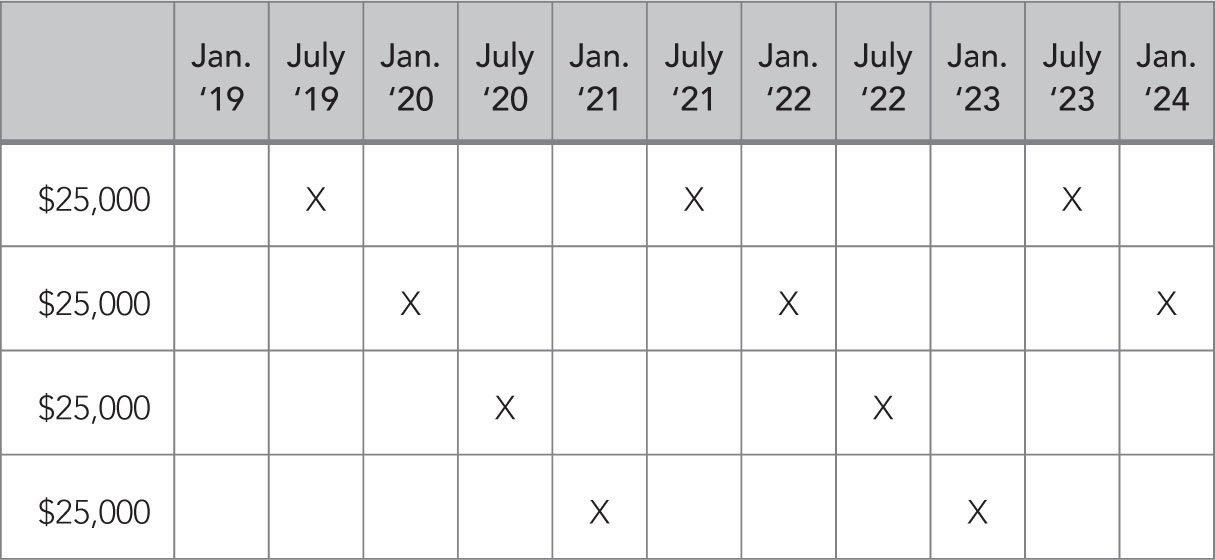

Then, as each term deposit matures, reinvest it for two years. Figure 15 shows how this is done.

Figure 15: Laddering $100,000

X is the year the deposit matures; you then reinvest it for 2 years

The advantages of laddering are:

• You have some money maturing every six months, in case you need it.

• After a while, all your money is in two-year deposits, earning usually higher interest.

• You won’t miss out entirely if interest rates rise. If they go up after you’ve set up your laddering, at least some of your money will mature soon to catch that rise. If rates fall, of course, the opposite happens. Some of your money will be reinvested at lower rates. But you’ll still have some money in at the old rates!

Rental property in retirement

As I explained in Step 5: ‘Boost your saving painlessly’, I have reservations about investing in rental property. It’s riskier than many people realise. And in retirement I think it can be even less suitable, because you can’t spend your capital – the money you bought the house with.

Sure, you receive rent. And by retirement you might have paid off the mortgage and so you keep a fair bit of the rent – after tax, rates, insurance and maintenance. But you’ve still got lots of money tied up in the house – money that you could be spending on fun.

However, I was recently put in my place by a man who told me he loves being a landlord in his retirement. He now has lots of time to work on his properties, adding value for himself, his tenants and his heirs. If that’s you, and you have plenty of income from rental properties or other sources, go for it! If your rental properties are mortgage-free, the investment is much lower risk.

True tale: Choose an adviser with care

A letter that I received nearly ten years ago for my Weekend Herald Q&A column shocked me. It was from a couple who were deeply worried about their retirement savings.

They had sold the family bach for $2 million, and gone to a financial adviser to find out where to invest the money. He had put them into two similar complex fixed-term investments, and since then the couple had watched in horror as their value fell to $1.6 million.

What’s more, they discovered that their initial expectation – that they would get their money back at the end – was not guaranteed.

It was a classic case of terrible diversification – just two investments, and both of the same type. Also, the adviser had failed to inform them of key characteristics of the investments.

As it turned out, many advisers were receiving generous commissions if they put clients into those investments. It doesn’t take a genius to guess that might have had something to do with the man’s advice.

Sadly for the couple, their only course of action was to hire a lawyer to try to get compensation.

The law has changed since then, thank goodness, and every provider of financial services must belong to a dispute resolution scheme. (For more information on dispute resolution schemes, see ‘If you have a problem’ (page 142) in Step 5: ‘Boost your saving painlessly’.)

Also, financial advisers are now more regulated, and are supposed to put clients’ interests before their own. (I wouldn’t count on that, though. For tips on how to pick an adviser who is much more likely to do well for you, see ‘One more thing: Do you need personal financial advice?’ towards the end of this book.)

Moral: Not all advice is good. Also, if you understand financial basics – like the importance of diversification – it’s much less likely you will end up in a situation like this. You’ve been reading this book, so you can already tick that box!

Step 7 check

Have you:

![]() Worked through the life expectancy calculator?

Worked through the life expectancy calculator?

![]() Considered our rules of thumb on retirement spending?

Considered our rules of thumb on retirement spending?

![]() Set an approximate savings goal?

Set an approximate savings goal?

![]() Thought about how you will make it easier to fund your retirement?

Thought about how you will make it easier to fund your retirement?

![]() Worked out how you will invest in retirement?

Worked out how you will invest in retirement?

Reward

Chocolates, cheese or flowers; or a ‘me day’ with a walk, book, time with family, being creative; or donating to a charity, or anything else that makes you smile.

What’s next? Let’s weigh up the pros and cons – and hows – of home ownership.