(WHEN IT’S THE RIGHT TIME – IF EVER)

In which we . . .

• Realise there’s a lot to be said for never owning a home

• Can’t go past KiwiSaver if you do plan on buying

• Consider becoming a renter-landlord, or a floating homeowner

• List essentials for home buyers

• Plan an auction strategy

• Consider all the mortgage bells and whistles

• Look into why and how to pay off a mortgage faster

• Smarten up a house for sale

• Learn how to inspire an agent to get you more when you sell a house

There’s no right stage of life to buy a home. Some frighteningly good planners and savers are in their first home in their early twenties. For others it might be in their retirement – or never. That’s why I haven’t numbered this step. Slot it in where it suits you.

That doesn’t mean it’s not important, though. Buying a home, or making a decision not to buy one and planning accordingly, is a key part of financial security. Let’s look first at deciding not to buy.

Not planning on home ownership

You don’t have to ever own a home to be financially well set up. This goes against the grain for many New Zealanders. We’ve been raised to dream of having a place of our own. But house prices – at least in 2018 – are out of whack with incomes, and out of reach for many would-be first home buyers.

It won’t always be that way. How do I know? Just by looking at history.

From the 1950s to the late 1980s, the average New Zealand house price was 2 to 3 times the average household annual income. Then house prices gradually rose, to 6.5 times income in 2008. They then dropped, but have since risen to about that level again. In Auckland, meantime, house prices in 2018 were more than 9 times annual household income.

That is way out of line. Generally, around the world, houses cost about three times household income – as they did here for 30-odd years just a few decades ago.

People have a tendency to think that whatever has been going on in the share or property markets for a while will continue, but it never does. House prices, as a multiple of average incomes, will fall again. It’s just that we don’t know when.

In the meantime, rather than complaining, if you feel shut out of the housing market think in terms of getting on with your life as a renter – and possibly staying that way for the rest of your life. You can always change your mind later.

Many people in Europe rent for life. In Germany, the home ownership rate is just over 50%, and in Switzerland it’s lower still. And they are not poor countries – far from it. These Europeans are happy to remain as tenants, usually with very long-term leases. It’s not uncommon to live in the same rented property all your adult life. The people treat their rented accommodation as their homes in a way that only homeowners usually do in New Zealand.

The circumstances in those countries are quite different from here. For one thing, the law tends to favour tenants more. Still, the tide might be turning in New Zealand. In a recent Consumer NZ survey of people who were renting accommodation, 64% said they rented because they can’t afford to buy. But another 26% said ‘It suits my lifestyle right now’ and 5% said ‘I like the flexibility of renting’.

It would be great if some landlords offered tenants longer-term leases – perhaps after a trial tenancy of, say, a year. That could suit both sides.

Weighing up the finances

Despite what your parents and others might say, renting for life doesn’t have to be a bad decision financially.

Key message: You can do fine as long as you reach retirement with lots of extra savings – preferably several hundred thousand dollars – to cover the costs of your accommodation for the rest of your life.

That might sound difficult – saving a whole lot more than people who own a home – but it doesn’t have to be.

Generally, it costs considerably more throughout life to own a home than to rent accommodation of a similar standard. Not only do you have to pay mortgage interest, but also rates, house insurance and maintenance. If you save the difference, and invest it wisely over the years, you might even end up better off than your homeowner friend on about the same income as you.

How do you know how much to save? Ask how much your friend spends on having her or his own home.

I’ve seen various calculations of who becomes better off – the homeowner or renter. The answer always depends on the assumptions you make. We could make one set of reasonable assumptions about house prices, mortgage interest, insurance, rates, maintenance, rent and returns on savings, and the homeowner would win. But with another set, the renter would win.

One thing is certain: if you’re a renter you won’t win unless you are:

• Disciplined about saving. It’s not clever to live the high life because your accommodation costs are cheaper. The best way to keep the savings rolling in is to set up an automatic transfer every payday.

• Willing to make higher-risk investments with your savings, so they get higher returns on average. A good choice would be a KiwiSaver or non-KiwiSaver growth or aggressive fund, which holds mostly shares. As you know by now, with these investments your balance will sometimes fall, but you need to stick with it through thick and thin.

You can probably transfer your savings directly from your bank account into a growth fund or, if the provider doesn’t take small regular savings, into a savings account, which you empty into the growth fund every now and then.

One clear financial advantage for the renter over the homeowner is that your savings can be more diversified. If you’re in a growth fund, you will be in a wide range of shares and probably also some bonds and other assets.

Weighing up other issues

An obvious negative of renting is that your landlord can kick you out. That would be especially bad if you have children – although longer-term leases could help reduce that risk.

Also, in most cases you don’t get to choose the carpets, paint colours, curtains and so on – although, again, you might with a longer lease.

There may be similar issues with the garden. If you’re a keen gardener, you’ll want some kind of guarantee that you won’t be asked to move out just when the vegies are coming into their own, or the hedge is getting bushier. And if you enjoy DIY or renovation projects, you can’t build up value in the property by adding a deck.

Also, over the longer term, you won’t have a property for your children to inherit. And there’s less security for your retirement in a rented property, although you could perhaps use your savings to buy a small home at that stage.

But there are some big advantages to renting:

• You don’t have to worry about maintenance and other responsibilities that can sometimes weigh heavily, both financially and psychologically, on a homeowner. As I once heard someone say, ‘Did you have a good weekend, or do you own your own home?’ If you’re renting and the roof starts to leak, you just call the landlord.

• It’s often easier for a renter to live close to downtown, which can be a big plus in these times of terrible rush-hour traffic.

• You can move house much more easily and cheaply than a homeowner.

• If you want to set up your own business, you could use some of your savings to do that, whereas a homeowner may have to raise a loan by adding to their mortgage.

For some people, none of this is as important as the pride of home ownership and the fact that you have more control over your living environment. But for others, the freedom that comes with renting is a big attraction.

True tale: Who needs home ownership?

A friend of mine, who helps businesses find money to expand, tells of a couple who suddenly received a windfall of about $750,000 when a company was sold.

‘They are from San Francisco, had migrated to New Zealand and were in their mid forties at the time, with two children in their late teens or early twenties,’ says my friend. ‘They had no debt and wanted to discuss investment options.

‘I asked if they owned a house. They said, “No,” and then explained that they are mystified by New Zealanders’ obsession with home ownership. They were very happy to be renters and had absolutely no interest in owning a home. They said in San Francisco’s Bay Area very few people their age aspire to own a home.

‘This doesn’t appear to be related to affordability. Rather, it is a preference to invest in other assets, once they are in a position to invest.

‘These are normal, sensible people, moderately well off but certainly not rich. Other than their accents, they are just like any other Kiwi of their age. I understand that this attitude is the norm in Europe, too, especially Germany.’

My friend continues, ‘With the obsession New Zealanders have with home ownership, and the “woe-is-me” hand-wringers who are distraught about declining levels of home ownership, I often wonder if it really is that sensible as a cornerstone of one’s investments.

‘The widespread attitude seems to be that the first investment Kiwis make is a home. And only after you get rid of the mortgage do you start thinking about other investments. If you don’t own a home you are somehow a failure. This seems to me to be totally wrong-headed as the basis of sensible personal investment.’

Moral: Buying a home is not the only way to financial security.

Still, most New Zealanders want to own their own home. And in most circumstances, the best way to save for a home is in KiwiSaver. (An exception to this will be described in ‘Thinking creatively’, below.)

As you’ve already read (‘Help to buy a home’ (page 68) in Step 4: ‘Join the best KiwiSaver fund for you’), everyone can withdraw their KiwiSaver money, except $1,000, to buy a first home. And people on lower incomes may also qualify for extra money from the government. What’s more, some people with modest assets who previously owned a home, but don’t now, may also be able to get a grant.

Even if you’re not eligible for a grant, you’ll save much more in KiwiSaver than elsewhere. Your savings will be boosted by the tax credit and, in many cases, by employer contributions.

The only possible negative is that you have to be in KiwiSaver for at least three years before you can make the withdrawal, and you have to contribute at a certain level to get the grant.

Some people worry that the rules could be changed, making them unable to withdraw their KiwiSaver money for a home purchase, but I can’t imagine that happening. There would be such an outcry that I reckon no government would dare to do it.

Having said that, you might want to put your extra savings – over and above 3% of your pay if you are an employee, or $1,043 a year if you’re not – into a similar non-KiwiSaver fund, perhaps run by the same provider. That gives you more flexibility. Check, though, that the fees are not much higher than in KiwiSaver.

If you’re saving for a first home, how risky should your KiwiSaver or other fund be? It’s the same rule as before. If you plan to buy the house within two or three years, you’re best off in a low-risk fund. If it’s three to ten years away, a balanced fund is good. If it’s more than ten years before you expect to buy, and you can tolerate the ups and downs, choose a growth or even an aggressive fund.

The rules for withdrawing your KiwiSaver money to buy a first home are fairly straightforward. But still, check with your provider well in advance of buying to make sure you cross all the ‘T’s and dot the ‘I’s. And if you’re hoping to get a grant, it’s important that you read the rules. Some people have got tripped up if they were, for example, buying land first and planning to build on it later.

Also, the government has adjusted the income and house price caps several times, and that’s likely to continue. And a few other rules have also been changed. So keep an eye on www.tinyurl.com/NZFirstHomeHelp.

Note that you can be pre-approved for a grant before you find a home. The pre-approval lasts 180 days. If you haven’t bought within that time, you need to apply again.

Be in for a chance with KiwiBuild

In mid-2018 the government started to take registrations for its KiwiBuild program, under which it plans to ‘deliver 100,000 affordable, quality homes over the next decade’.

This is entirely separate from KiwiSaver help for first home buyers. Eligible people go into a ballot for the chance to buy a newly built home.

If you’re in the market to buy a home, you can read more about KiwiBuild and perhaps register your interest at www.kiwibuild.govt.nz.

You have to be a first home buyer or someone who qualifies as a previous homeowner under the asset test for the KiwiSaver HomeStart grant (refer back to page 70, ‘Previous homeowners’, in Step 4: ‘Join the best KiwiSaver fund for you’).

But the rules are different from the KiwiSaver HomeStart rules. You must intend to live in the home for at least three years. And single purchasers must have an income below $120,000. For couples, the income cap is $180,000.

The price caps for the houses in Auckland and Queenstown are: $500,000 for a one-bedroom house, $600,000 for two bedrooms, and $650,000 for three or more bedrooms. In other areas, there is an overall price cap of $500,000.

Note that income and price caps may change. Check the website.

Thinking creatively

If you can’t afford to buy near where you work and want to live, one way to get into the property market is to become a ‘renter-landlord’.

In a 2018 survey, BNZ asked ‘aspiring first home buyers’ what they were prepared to do to get on the property ladder. About 44% – mainly in Auckland or Wellington – said they would buy a property and rent it out, either in a cheaper part of their city or somewhere else in New Zealand.

The basic idea is presumably that you’re ‘in the market’ if property prices keep rising fast, making it easier to buy your own home later. It’s not a bad idea, but you need to go in with your eyes open.

For one thing, you’ll probably kiss goodbye to KiwiSaver first home help. You can’t buy a rental property using your KiwiSaver money or a HomeStart grant. Those are available only if you live in the house for at least six months after buying it. And if you want to buy your own home later, you won’t be eligible for the withdrawal or grant because you already own a property, says a Housing NZ spokesperson.

‘Clearly, if they sold the rental, then they could apply as a previous homeowner, once they no longer owned any interest in (real) estate. However, it would mean that they have to meet the realisable assets test, which would not be required if they were first home buyers,’ he adds.

If you go back to the section ‘Previous homeowners’ (page 70) in Step 4: ‘Join the best KiwiSaver fund for you’, you’ll see that your ‘realisable assets’ have to total less than 20% of the house price cap for existing properties in the area where you plan to buy. Realisable assets would include the proceeds you’ve made from selling the rental, plus all the other things listed in that section. So chances are your assets would be too high – especially if you’ve made gains on the rental property.

There’s one way around this. If you’re thinking of buying a rental in a cheaper part of town – as opposed to elsewhere in New Zealand – you could buy the property as your own home and live in it for at least six months, and then move elsewhere while keeping it as a rental. Or who knows? Maybe you’ll discover you like living there!

There are also other concerns about becoming a renter-landlord:

• These days, in most cases you need a higher deposit – 35% at the time of writing – to buy a rental property compared with 20% for your own home. Still, 35% of $300,000 in a cheaper area is $105,000. That’s way less than 20% of $1 million ($200,000) in a posher suburb.

• If you sell the property within five years, you will probably be taxed on your gains under the so-called ‘bright line’ rules introduced in 2018.

• Owning a rental property is not easy. Read the section titled ‘Rental property’ on page 132.

• Property prices in many parts of the country seem to be slowing or even falling, and it wouldn’t be surprising if there are more widespread falls in the next few years. Also, price rises tend to vary hugely around the country, and even from suburb to suburb. Be prepared to possibly have to sell at a loss.

Sorry to be a wet blanket. The idea might still work well for you.

Other results of the BNZ survey of aspiring first home buyers:

• 30% of the people would buy a shared property with their family.

• 21% would go ‘tiny’ and buy an apartment or unit under 80 square metres to live in, and another 12% would buy a tiny apartment or unit in another town to rent it out.

• 14% would buy a shared property with friends.

• 19% would buy land outside of the city they live in.

All these ideas have merit. Tiny properties are a bit of a trend, which goes hand in hand with the idea that we all have too much stuff. But you might want to try out the idea first by living in a caravan for more than a few weeks!

Getting help from family members – often parents or even grandparents – to buy a first home is becoming increasingly common. If you share a purchase with family or friends, I recommend you work out in advance what you will do if someone is unable to make agreed payments for a period, or if a relationship break-up changes how things work, or if somebody becomes disabled or dies. Be pessimistic. It’s much better to work these things out in advance than when the crisis happens.

Then put all the details into a formal agreement drawn up by a lawyer. That sounds heavy and unnecessary, but I’ve seen families and great friendships break up for the want of such an agreement.

A floating home

In early 2016, I ran a series of readers’ letters in my Weekend Herald column about living in a boat on a marina.

One correspondent reported that the upfront cost can be as little as $70,000 to $80,000 for a boat, marina licence and secure parking. Another said a 40-foot boat costs about $50,000 to $80,000, and a marina berth $7,000 to $9,000 a year. The bigger the boat, the more the berth costs. There can also be a ‘live aboard fee’.

One reader warned that boats shouldn’t be seen as investments. You’re unlikely to get back your purchase price plus what you’ve spent on maintenance – which costs about 10% of the boat’s price each year, and more if you’re not handy.

She added that not everyone wants to live in such close quarters with their partner or family, as there’s very little privacy. And in many cases you have to use public facilities for washing and showering. Still, she said, it’s wonderful to be able to head off in your home for weekends and holidays away. There’s some appeal in that!

Making the purchase of a first or subsequent home

Whether you’re buying your first home or your 17th home, you may be tempted to try to time the market – waiting for prices to fall if they have been rising. Don’t. You might end up putting your life on hold for years, while prices keep climbing. As someone once said, ‘The best time to buy a home is always five years ago.’

Sure, you’ll be unhappy if you buy and then prices fall soon after, but it’s best to take a philosophical attitude to that. Over the years, you’re quite likely to buy and sell several homes. You will probably have good luck with your timing sometimes and bad luck sometimes. That’s life!

It’s important to note, when you’re looking for a home to buy, that real estate agents are paid by sellers and are there to represent them – not you. Of course they’ll be friendly to you. They can’t get a deal through without a keen buyer. But they’re not acting in your interests.

Remember back in Step 5: ‘Boost your saving painlessly’ we were talking about scams and I said don’t ever give in to pressure from salespeople? The same applies to buying property. There’s usually no scamming going on, but agents can be adept at making you think someone else is about to buy the property and you’d better get your offer in fast.

Sometimes it’s true of course. But if another person does make an offer, the agent should at least get back to you to see if you want to offer more.

Key message: Buying a house is a big decision. Do not let anyone pressure you into making that decision quickly.

If you’re seriously thinking of buying a property:

• Get hold of a LIM – or land information memorandum – on the property. This is issued by the local council, and gives you info on things like: rates; potential erosion, slippage or flooding; drains on the land; possible health hazards; and resource planning consents. LIMs usually cost around $250 to $400, so ask the agent listing the property if you can get a copy of the most recent LIM from them. If not, it’s worth getting your own.

• Go to the property at different times of the day, and perhaps during the week and on the weekend, to check how much sun it gets, whether there’s a noise problem, and whether there’s always plenty of parking for you and your visitors.

• Check out the neighbourhood. How close are schools, public transport and shops, and how good do they look? You might not need a school or a bus, but it will affect the value of your property when you come to sell later. You can learn quite a lot just by driving by and walking around, or perhaps knocking on a neighbour’s door.

• Go to www.qv.co.nz to get the rating valuation of the property, and the others near it. That’s free, but you can also pay to get more info on the property. It’s worth spending a bit of time on this website. Another website to explore is www.homes.co.nz.

• Hire a registered builder or other qualified house inspector to check out the property. If at all possible, go with him or her on the inspection. They will give you a written report later, with photos, but you learn more if you’re on the spot. The inspector might, for example, point out a defect or dampness problem, and you can discuss how it might be fixed and what it might cost. If you can, get into the attic and under the house with the inspector to check things like insulation and foundations. It’s surprising what you’ll learn.

A building inspection will cost you several hundred dollars. Before spending the money, consider asking the seller’s agent if you can make an offer on the property conditional upon getting a satisfactory inspection. If they baulk, you’ve got to wonder why.

Key message: If after doing all this you can’t negotiate a reasonable price for the property, you must be prepared to walk away.

It may be hard. By now you’ve probably been thinking about where your furniture would go, what colour you would paint the dining room, and how you would change the garden. You might also think this is the only place for you. But it’s not. Believe me, because I’ve been there more than once. You will find another even better place.

Buying at an auction

Auctions have been more common around Auckland than elsewhere in New Zealand, but still you might find yourself bidding in an auction anywhere around the country.

If you plan to do this, it’s important to go to some other auctions first and watch how they work. It’s quite fun, actually, and there can be sometimes be a bit of drama.

When it comes to the auction you’re interested in, rule number one is that you set a maximum bid before the auction, and do not bid past it. If you pay too much for a property, it can really knock you back financially. You must go to every auction being prepared to lose.

A lot is written about bidding techniques. Who knows how good the advice is? But one trick I’ve found that has worked several times is to not bid at all until it seems the last bid has been made. The auctioneer is, perhaps, raising his or her gavel, ready to call, ‘Sold.’ Then you make your bid. What’s more, you jump the price. If the last few bids have been $1,000 apart, you jump by $3,000. For example, the bids go $672,000, $673,000, $674,000, and then you say $677,000.

The last bidder will not be happy, but that’s the game. In their despondency, they will quite often stop bidding, and the place is yours.

Normally you can’t put conditions on buying at auction. However, you can always approach the seller’s agent beforehand and explain that you will bid only if there’s a prior written agreement that if you win you will buy under certain conditions. I did that once when I needed a longer settlement date, and it worked fine.

If you can’t get an agreement like that, and you’re not prepared to bid without it, all is not lost. Quite often, especially in quieter markets, the property will be passed in because the bidding doesn’t reach the seller’s minimum price, known as the reserve. The agent – who knows you by then because you’ve tried to get the agreement – should at that stage come back to you. At that point you can make a conditional offer.

True tale: Sell before you buy

Remember back a few steps when I wrote about losing 30% on a house? That was partly because the housing market had plunged, but also because my husband and I had to sell in a hurry. We had already bought another house, and were facing huge double mortgage payments.

The situation arose – as these things often do – because we fell in love with a house with a sea view that was just down the road from close friends. It was being sold by auction, so we couldn’t make an offer conditional upon selling our old place for at least a certain price. We took the risk and bought anyway – paying not much more than what we thought our old place was worth. After all, we figured, we were buying and selling in the same market.

In the weeks that followed, we did all we could to sell our old house at a reasonable price. But there’s only so much you can do while waiting for buyers to come. In the end we took the house to auction. Lots of people – including nosy neighbours – turned up, the house looked attractive in the sunshine, and the bidding seemed to start well.

But then the auctioneer took us aside. In those days, an auctioneer could pretend to be taking bids if there were no real ones, and that’s exactly what he was doing. Nobody had made a single bid. I’ll never forget hearing that. A few days later we sold the house for a song – just to end the nightmare.

Clearly, house prices had dropped much more in our old suburb than in the new one. But it wasn’t just that. We were desperate sellers because we had already bought our next house.

I know, I know . . . you want to buy before you sell because you’re fussy. You may not want to move at all unless it’s to a place you really like. And if you see the place of your dreams, you’ll want to grab it, and worry about selling the old place later. But that’s a risky strategy, as I learnt.

It’s far better to have sold first, for these reasons:

• You know exactly how much money you have. Also, you’re a ‘cash buyer’, which puts you in a stronger position to negotiate.

• The ball is in your court. If you’ve already signed a deal to sell your old place, you can spend every spare minute looking at houses, which is so much better than sitting around hoping somebody will buy your old property.

• It’s better to end up with no house for a while – staying with friends or family or doing a deal with a local motel or hotel or Airbnb – than having to pay two mortgages or expensive bridging finance.

Tip: If you sell first, ask your buyers if they would like a long settlement period. That gives you more time to find a new place, and often it suits the other side, too. Don’t just accept what the agent tells you is the standard period.

Moral: Back in Step 6: ‘Stay cool’ I talked about never getting yourself in a position where you’re forced to sell. That applies to homes as much as to investments.

A mortgage, a lawyer friend tells me, is strictly speaking not a loan, but a document that outlines how the loan is secured by a property. But to most of the world, a mortgage is the loan itself. And if you don’t pay it back, the lender can sell the property to get their money back.

We’ve already talked about mortgages several times in this book:

• In Step 2: ‘Kill off high-interest debt’ we looked at reducing your mortgage versus investing.

• In Step 4: ‘Join the best KiwiSaver fund for you’ we looked more specifically at that question versus investing in KiwiSaver.

• In Step 5: ‘Boost your saving painlessly’ we looked at taking out a mortgage to buy a rental property, and how the lucky geared investor did very well but the unlucky one ended up with no property and a debt to the bank.

Those lucky and unlucky examples also apply to someone borrowing to buy their own home. And, occasionally, there’s a similar sad ending if the homeowner is forced to sell. Usually, though, people don’t give up their home without a fight. And let’s face it – few of us could buy our first home without getting a mortgage.

In this section, we’ll look in more depth at what for most people is by far the biggest debt they take on in their lives. And it’s not just the debt, but the interest on it. It’s not uncommon for you to end up paying back twice what you borrowed or more over the course of a mortgage.

If you just blunder into the mortgage maze, you can wind up much worse off than you need to be. It’s well worth knowing your way around.

Let’s start with a warning: Just because a bank will give you a mortgage of a certain size doesn’t mean you will find it easy to repay it. Sometimes the banks have plenty of money sloshing around and are too keen to lend. Don’t rely on the lender – work out for yourself whether you can manage the payments.

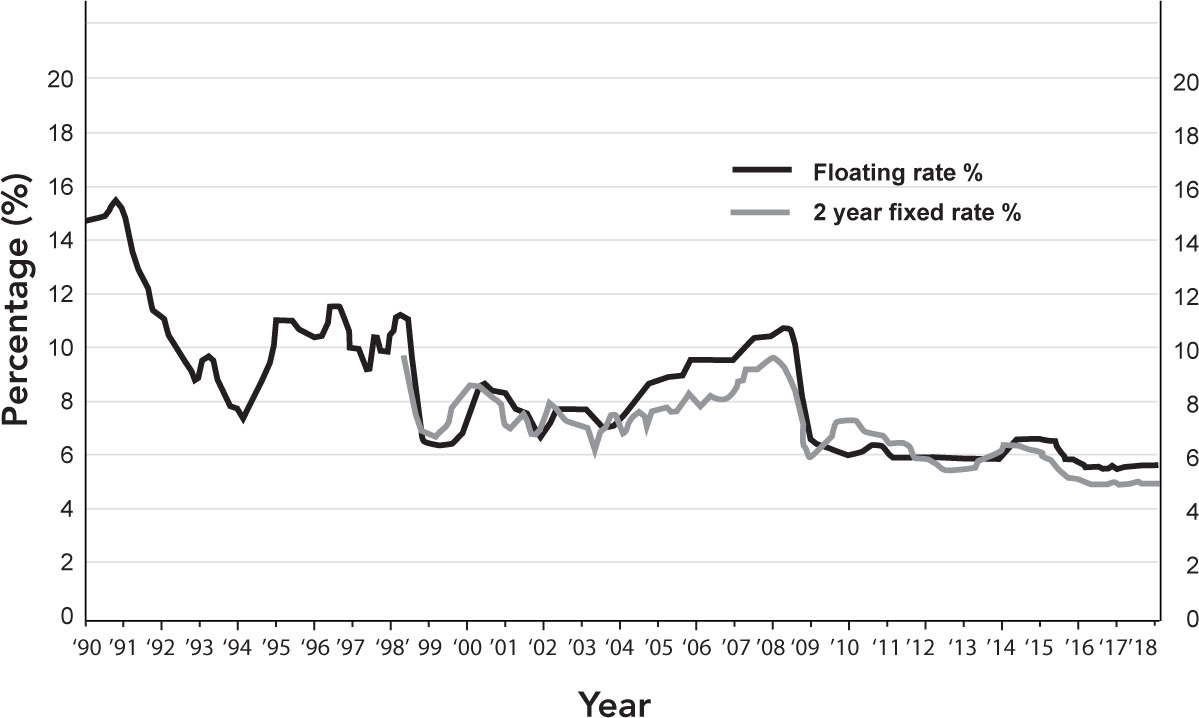

Figure 16: Mortgage interest rates

Sometimes floating rates are higher, sometimes lower

Source: Reserve Bank of NZ (rates offered for new customers)

Figure 16 shows:

• Current mortgage rates are unusually low by historical standards. True, that’s partly because inflation is lower than it used to be. But still, inflation has been mainly below 4% since the early 1990s, and yet mortgage interest rates have several times risen above 10% since then.

• Fixed-rate mortgages are not always at lower interest rates than floating mortgages, despite recent history.

There are no guarantees that rates won’t go back up above 10%, or that fixed rates will stay below floating rates. Anyone taking out a mortgage needs to keep that in mind.

If you can’t cope with a mortgage rate rise

The first thing to do is talk to your mortgage lender. If you talk before you get behind with payments, they are much more likely to accommodate you. Some possible solutions:

• Pay interest only for a while – although sometimes this doesn’t reduce payments by very much. And you’re making no progress on reducing the loan, so do this for as short a time as possible.

• Lengthen the term of the loan. If you have a 20- or 25-year mortgage, make it 30 years, or even 35. This does mean, though, that you’ll pay lots more interest over the life of the loan. Go back to a shorter term later if possible.

The situation is similar if for any other reason you can no longer make mortgage payments. If approached early, a lender may reduce your payments for a while, or offer one of the above alternatives. Whatever the solution, you will end up paying more total interest. But it sure beats a mortgage foreclosure – the forced sale of your house to repay your mortgage.

True tale: Take care with extra borrowing

Says a friend, sadly: ‘My elder daughter and her husband bought and sold several houses in succession in the Waikato. Each time they sold for more than they paid, but each succeeding house cost more and involved a higher mortgage.

‘Their small business was then severely hit by the global financial crisis and folded. The business had been financed in part by the equity in their house, and they lost both their income and the house when they could no longer pay the mortgage. They now rent in Hamilton.’

Moral: It can be risky to ‘borrow against the equity in your home’ – which basically means you increase your mortgage to raise money for something, often a business. When people first do it, they are always full of hope and don’t imagine things could go wrong. But when bad stuff happens, and you lose your home as well as your dreams, it’s pretty rough.

Types of mortgages

Don’t skip this bit if you’ve already got a mortgage. There’s a pretty good chance you haven’t got the best one for you. If you decide another type would suit you better, your lender may let you switch – although if you have a fixed-term loan you will probably have to wait until the term ends. If the lender makes it difficult to shift, ask another lender if you can move to them, or discuss your situation with a mortgage adviser or mortgage broker.

More on them shortly. But first, the basics.

There are several types of mortgages available. We won’t go into the more uncommon choices, like whether you want a reducing (or straight-line) mortgage – in which payments are higher at first but decrease over time as you pay down the loan. Given how high house prices are these days, there would be little demand for that.

But the following are options you should consider.

Fixed or floating interest?

As we’ve just seen in Figure 16, fixed-rate mortgages tend to be lower than floating these days. But by the time you read this, it could be the other way around.

A fixed rate gives you certainty of payments, at least for the term of the loan – although you could be in for a shock if rates rise and your interest jumps at the end of your term. If you’re on a floating rate, your interest would rise more gradually.

A big negative of fixed-rate loans is that there are often penalties if you want to repay the loan early – before the year or five years or whatever is up. You might think, ‘That won’t happen to me. Where would I get the money from?’ But people are sometimes surprised by a redundancy payment, an inheritance, a big win or some other windfall.

Early repayment penalties vary widely, depending on what’s happened to interest rates since you got your loan. That’s why lenders won’t tell you in advance what your penalty will be. They’ll give you a formula or something, but it will depend on rate movements, which nobody can accurately predict.

Let’s say you have a five-year fixed-rate loan at 5%. Three years into the loan, you want to pay it back.

• If interest rates have risen in the meantime, the lender might not mind if you pay back the loan early. They can then lend out that money at a higher rate. So your penalty might be small or even nothing.

• If interest rates have fallen, the lender really wants to keep your loan going, bringing in what have become really good returns for them. Your penalty in that situation can be huge.

Back in 2008–09, when mortgage interest rates plunged (see Figure 16), many people with fixed-rate mortgages naturally wanted out, so they could move to a much lower rate. But of course the lenders weren’t interested, and quoted penalties of many thousands of dollars.

To get a rough idea of what your break fee would be, go to www.tinyurl.com/NZBreakFee. This is a calculator put together by www.interest.co.nz.

However, all is not lost if you want to reduce your mortgage but you face a huge break fee. Many lenders will let you either pay off a certain amount in a lump sum or increase your regular payments up to a certain amount, perhaps 20%. Others will permit extra payments of up to $1,000 a month as long as you commit to making those extra payments until the term of the loan ends.

Key message: If you want to repay a fixed-rate loan faster, don’t assume the worst. Ask your lender. And when you renew a fixed-rate mortgage, negotiate for more flexibility in future.

So where are we on the fixed versus floating question? Don’t choose just on the basis of interest rates at the time you borrow. That can easily change. Make some of your loan fixed and some floating – perhaps half and half or, if the two rates are very different, two-thirds and one-third.

But do include at least a portion floating, so you can pay it back quickly, no questions asked, if you happen to get a windfall. Also, a floating loan is more flexible. It can be an offset, redrawable or revolving credit mortgage. More about those options shortly.

Which fixed term?

Let’s say you’re choosing between paying:

• 5% for one year; or

• 6% for five years.

The one-year deal looks better. But by the time you renew it, rates might have risen. Five years down the track you might end up having paid more than if you’d gone with the longer term. On the other hand, if interest rates fall – or don’t rise much – you’ll wish you had stuck with the shorter term.

It’s best to have a portion of the loan each way. Then at least you’ll be content with some of your total mortgage.

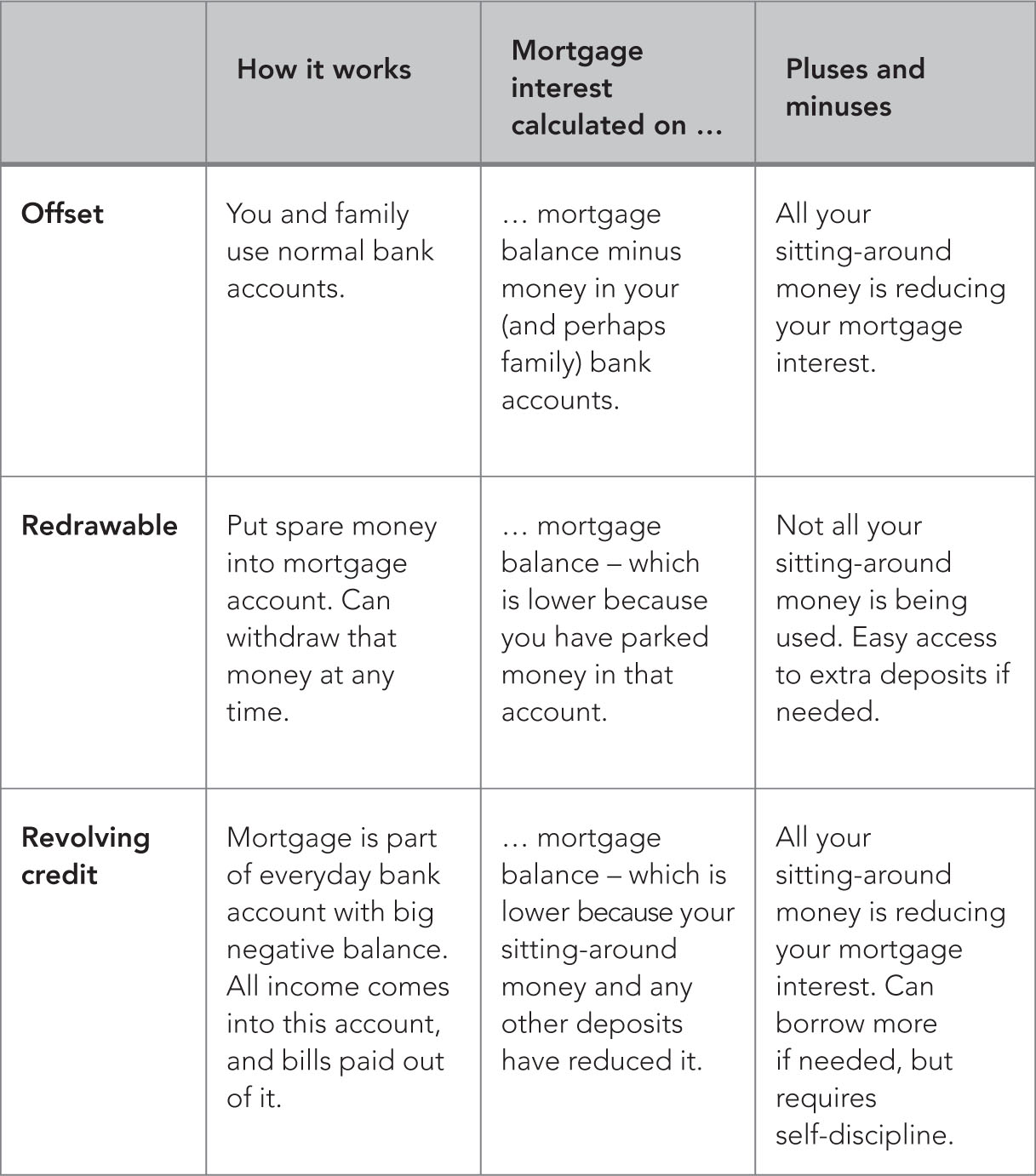

Traditional, offset, redrawable or revolving credit?

This is where mortgages get interesting. Yes, really. You choose one to go with your lifestyle, how often you get paid, and how strong your willpower is. And in the process, you can pay off the loan faster.

A traditional mortgage

In a traditional mortgage, you make your regular payments – usually fortnightly or monthly. In the meantime, you have money sitting around in your everyday bank account to pay your bills and cover your day-to-day expenses, and hopefully also in a rainy day account or other savings account.

That sitting-around money is usually earning zero or low interest. That means you’re paying, say, 6% on your mortgage while earning very little on your sitting-around money, and even less after tax. No wonder bank profits are so big!

But there are three ways you can turn that around, making things more even between you and your lender. The following types of accounts are not all offered by every lender, but they are around if you look for them. As far as I know, all are available only on floating-rate loans.

An offset mortgage

In an offset mortgage, you pay your mortgage out of your regular bank account. But the balances in all your accounts – and in some cases other accounts owned by family members – are added up and subtracted from the mortgage. So you pay interest only on the lower amount.

None of the accounts earns any interest – but that’s probably no big loss.

For example, you have a $300,000 30-year mortgage at 6%, and currently the bank account balances total $5,000. So you pay interest on $300,000 minus $5,000, which is $295,000.

How much difference does that make?

The mortgage calculator at www.sorted.org.nz tells us that if you had a traditional mortgage you would be paying $1,799 a month, and over the life of the loan you would pay a total of $347,515 in interest. (That’s more than the mortgage itself – so you pay back more than double what you borrowed. Gulp!)

With the offset, you would pay $1,769 a month, and $341,723 in interest. That amounts to:

• Thirty dollars less a month, which doesn’t seem much, but it adds up to $10,800 over the 30 years.

• Nearly $6,000 less interest in total. That’s not some theoretical amount, but real dollars in your hand to spend later in life.

What’s more, you might decide that with this arrangement you can afford to raise your mortgage payments by the $30 a month. If you add this in, bringing your monthly payments back up to $1,799:

• The total interest you will pay over the life of the loan is more than $24,000 less than with a traditional mortgage. Wow!

• The 30 years to pay off the loan has dropped a little to 29 years. One more year of mortgage freedom is worth something.

A redrawable mortgage

In a redrawable mortgage, you have a separate bank account for your mortgage, and deposit your mortgage payments into it. At any time you can put in more money – either as a lump sum or bigger regular payments. The big plus is that you can go back to the original minimum payment at any time, and you can take out any of the ‘overpaid’ money if you find you need it.

By parking money in the account for a period, you reduce your balance for a while, and hence your interest payments.

A revolving credit mortgage

In a revolving credit mortgage, your mortgage is part of your everyday account, so it may have a balance of, say, minus $500,000, which can look alarming at first. All your income is deposited into that account, and all your bills paid out of it. In the meantime, that income is credited against the mortgage. The mortgage balance is therefore lower, so you pay less interest.

At any time you can increase your borrowing again – in some cases up to the original limit, although some lenders have a reducing limit, which forces you to pay down the loan over the years.

The idea of a revolving credit mortgage is that, over time, you have more money going into the account than coming out again, so your mortgage balance – the negative value of the account – decreases, finally to nothing.

Revolving credit loans work particularly well for self-employed people with lumpy incomes – sometimes large sums that are used only gradually over several months. They can make good use of their money before it is gradually spent. It can also work well if you plan to renovate your home, as you can withdraw a large sum at any time without having to apply.

I had a revolving credit mortgage for years, and it worked well. I regarded it as a bit of a game to get income into the account as fast as possible and put all bills on automatic payment on the last possible day.

However, if you’re not disciplined about getting rid of your mortgage, this type of loan might not be for you. You might be too tempted to withdraw money from the account – effectively adding to your mortgage – for a holiday or a shopping splurge.

A personality test: Do you always pay off your credit card in full each month? Do you generally spend less than you earn? If yes, you’re probably a good candidate for a revolving credit mortgage.

Figure 17: Three clever types of mortgages

Basically, all three of these types of mortgages work in much the same way. The set-ups are different, but with all of them you make use of your sitting-around money to pay less interest. The interest is calculated daily, so even if you park money in an account for a few days it all helps.

With less money being wasted on interest, more can go into reducing the principal – the amount you borrowed in the first place. So you end up paying off the loan faster.

Note that it might cost you more to set up an offset, redrawable or revolving credit mortgage than a traditional loan, and some lenders charge a monthly fee. But in most cases the advantages more than make up for that.

A great place for rainy day money

If you have an offset, redrawable or revolving credit mortgage, keep your rainy day money in your bank account, so that it’s keeping down the mortgage balance until you need it.

Monthly or fortnightly payments?

Every now and then you hear someone say that you can cut the amount of interest you pay – and the time it takes to pay off your mortgage – by simply switching from monthly payments of, say, $1,000 to fortnightly payments of $500, half the amount. They sometimes present the idea as some kind of clever trick.

But there’s no magic. While there are, of course, 12 months in a year, there are not twice as many fortnights, but 26. So you make extra payments each year. Of course you’ll pay the mortgage off faster.

Still, fortnightly payments might suit you better than monthly if you are paid fortnightly. The downside is that if you have other payments that are monthly, such as electricity or phone bills, and you’re on a tight budget, it can wreak havoc in the couple of months each year when there are three rather than two fortnightly mortgage payments.

Shopping for a mortgage

Your first step is to look at a table of current mortgage rates. A good source is www.interest.co.nz, or you can look each week to the right of my Weekend Herald column, in the business section. That will give you an idea of what’s out there.

Don’t confine yourself to your own bank. There’s no reason why you can’t get a mortgage from a different lender.

But rather than just looking at who offers the lowest rates today, it’s better to look at long-term trends. After all, today’s lowest mortgage provider might raise its rates tomorrow. To compare different banks’ rates since 2002, go to www.tinyurl.com/NZMortgageRates.

Then, to get an idea of what your monthly or fortnightly payments would be with a certain mortgage, I recommend the mortgage calculator on www.sorted.org.nz, although there are many others online.

A good next step is probably to go to an independent mortgage adviser or mortgage broker. They will help you find a suitable loan, and they know things like which lenders are more sympathetic if you have a bad credit record or low income.

You don’t pay the adviser, and they should get you as good an interest rate as you could on your own. But, as in any other situation when somebody is offering you something free, you should ask what’s in it for them. In this case, if the mortgage adviser organises a loan for you, that lender pays the adviser commission.

This can be a worry. If one lender pays more than another, the adviser may tend to favour them. Also, mortgage advisers don’t deal with every lender. So it’s important to ask them which lenders they’re not considering, and also how much commission they get from the different lenders.

This might feel like an awkward conversation, but it’s your money at stake. Just say I told you to ask! If they are not happy to answer, that in itself should tell you something. Keep in mind what they tell you, and check that you can’t get a better deal from a lender they don’t work with.

But I don’t want to be too negative. A good mortgage adviser knows lots about the different bells and whistles that lenders offer and how to approach the lenders. And if they want to keep a good reputation, they’ll do their best for you.

It was actually a mortgage adviser who gave me the following tip: don’t automatically go for a 30-year mortgage. Banks usually suggest 30 years, the adviser says, but that may be because they get more interest out of a longer-term loan.

Let’s look again at our $300,000 mortgage at 6%:

• Over 30 years, you would pay $1,799 a month and total interest of $347,500.

• Over 25 years, you would pay $1,933 a month and total interest of $279,900.

• Over 20 years, you would pay $2,149 a month and total interest of $215,800.

Take a close look at those numbers. Moving from 30 to 25 years you pay just $134 more per month. And what do you get for that? More than $67,000 off your interest bill. And you’re mortgage-free five years earlier.

What if you go the whole hog, to a 20-year mortgage? Sure, you have to pay $350 more a month than on a 30-year loan. But you’re more than $131,000 better off. And you’re mortgage-free a whole decade earlier.

On a mortgage twice as big – $600,000 – double the figures above.

True tale: Never give up

Back on page 114, under ‘Champion savers’, I wrote about a woman who saved for a house while earning $30,000 a year. How did she get a mortgage on such a low income? Persistence. She had a 75% deposit when she approached several banks for a loan. Three said no, but one said yes.

With the loan, she bought a two-bedroom Auckland house for $500,000. She’s paying off the mortgage at $600 per month – almost certainly less than the rent she had been paying.

Moral: Don’t get discouraged. Not all lenders are the same.

Reducing a mortgage

We’re not talking here about making the regular minimum payments you must make on most mortgages. It goes without saying that you should do that. And, as I said above, if you can’t it’s essential that you discuss that with the lender.

In most cases, though, people make regular mortgage payments year in year out until the loan is paid off. But – as teachers used to say on our school reports – we could do better.

I read recently that only 13% of New Zealanders with mortgages say they can’t afford to pay more than the minimum mortgage payments. That means the rest – quite likely including you – could stretch themselves further. It’s a super idea.

Getting rid of your mortgage means more than just no longer having to make payments – although that’s pretty good.

It also means you have guaranteed accommodation, no matter what happens to house prices or your financial situation. And should you get into financial trouble – or need money to help out family members or invest in your daughter’s new hi-tech business – you will probably be able to borrow back against the house. Without a mortgage, you’re also in a much better position to take on higher-risk, higher-return investments.

Apparently, the average New Zealander clears their mortgage at age 60. Set a goal to do it younger. (See ‘Setting a goal’ on page 26.)

Nearly always with a floating-rate loan the lender will accept higher payments. As noted above, that might not be the case with a fixed loan, although you should always ask. If your request gets you nowhere, wait until the end of the term and then make part of the loan floating.

There are various ways to pay down a mortgage faster:

• The easiest way: When interest rates fall on a floating-rate loan, simply continue with the old payments. This is likely to happen several times in the course of a mortgage, and it’s a great opportunity.

• Go to the lender and renegotiate a shorter term. You might have started out with a 30-year loan but after a while – perhaps after a few pay rises – you realise you could cope with a 20- or 25-year loan.

• If you have an offset, redrawable or revolving credit loan, you can simply hold more money in your bank account. That will be subtracted from the mortgage balance, and so has the same effect as reducing the balance.

• Switch from monthly payments to fortnightly payments of half the monthly amount. But see the note of caution a few pages back.

Let’s look at an example of the first option – maintaining your payments when the interest rate drops. On our $300,000 30-year loan, at 6% you pay $1,799 a month. If interest rates drop to 5.5%, you pay $1,703 a month. But if you keep the payments at the old $1,799, you will pay up to $79,000 less interest and pay off the loan up to three years earlier – depending on how far through the 30 years you are. Nice!

To do your own calculations, go to the mortgage calculator on www.sorted.org.nz. Play around with it. See what happens when you increase your repayments.

Let me repeat what I said before: the interest savings are real dollars – extra money you’ll have. Think what you could do with $79,000 more in retirement. Actually, it will be more than that, because in the meantime it will have grown through compounding returns.

Someone once said, ‘Rich people never know the satisfaction of making that last mortgage payment.’ And it is a great feeling. By all means celebrate, perhaps blowing what would have been your next mortgage payment on a treat.

After that, it’s time to get into serious retirement saving with the money that used to go into mortgage payments. If you’ve paid off the mortgage faster, you’ve got that many more years to build up a decent sum with which to have a great retirement.

True tale: A narrow focus

‘I’m the trustee of someone’s small family trust,’ says a friend of mine. ‘They still had a mortgage over their house, held in the trust, and they got an inheritance of about $1 million. Somehow they met a personal financial adviser from a big well-known firm, who wanted to pitch to put the $1 million in a non-KiwiSaver balanced fund. The couple asked me to come to the pitch.’

My friend realised that the return on the balanced fund, after tax and fees, was about three percentage points less than the mortgage interest they were paying. So they would be much better off using the money to pay down the mortgage.

‘The adviser was looking at the $1 million in isolation, ignoring the rest of the portfolio,’ says my friend. He talked the couple out of taking the adviser’s advice.

Moral: There are three morals here – give priority to reducing a mortgage (with the exception of contributing to KiwiSaver); consider your whole range of investments and debts; and beware of advisers who are overly keen on investing your money – probably because they will get commission for it. (More on that shortly, in ‘Do you need personal financial advice?’, page 271.)

Depending on why you are selling your home, you might not have a lot of time to prepare it for sale. But it’s a really good idea to spend a few weeks smartening the place up. I’ve heard too many stories of people selling their house as is, only to hear within a year that the buyer spent, say, $50,000 on some clever improvements and resold the house for $200,000 or $300,000 more than they bought it for. Ouch!

Pay particular attention to the first impression buyers will get – whether that be your letterbox (which they’ll be looking for to check they are at the right house) or the gate, garden and front door. Think like a buyer. We’ve all looked at houses and been put off before we even entered the place. Also consider getting the house painted. It doesn’t cost a great deal to make a house look much smarter.

Experts say that kitchens and bathrooms can make or break a sale, so consider putting in a new kitchen or bathroom. If the old one is less than, say, 20 years old, it may not be worth it, but spending the same amount replacing a tired 50-year-old kitchen or bathroom is likely to pay off. Another feature that apparently helps to sell a house is adding a deck – although not every place lends itself to that.

These days, quite a few houses for sale are ‘staged’, with a company coming in and adding flash furniture, art and so on. You might want to hire an expert, or you can read a few online articles and do it yourself.

A major point the companies make is to ‘declutter’. If you’ve got lots of stuff around the house, put it in cartons at a friend’s place. And at the very least, buy a few bright cushions to liven up the living room or a couple of mats to cover carpet stains.

By the way, home buyers should be aware of this. If you’re getting serious about buying a house, lift the rugs, and try to look beyond the staging!

Real estate agents’ commissions

You don’t have to use an agent to sell your home. It’s getting easier, with the internet, to get the word out about your wonderful property, and you can find online support for selling on your own, often called ‘selling privately’. Start with the Citizens Advice Bureau website, which lists pros and cons of private sales.

I’ve sold my own house once, in Chicago. The most difficult part was negotiating with two keen buyers. But in retrospect I could have hired someone, perhaps a lawyer, to do the negotiations for much less than real estate commission. The rest – advertising and running open homes – wasn’t so difficult. Some of you might want to give it a go.

But it takes time, effort and research. Probably most people prefer to hire an expert.

While a lot of the big real estate companies charge similar sales commissions, there are some that are considerably cheaper.

It’s important to know, too, that you can negotiate commissions. This works especially well in a slower property market, where agents are extra keen to get your listing.

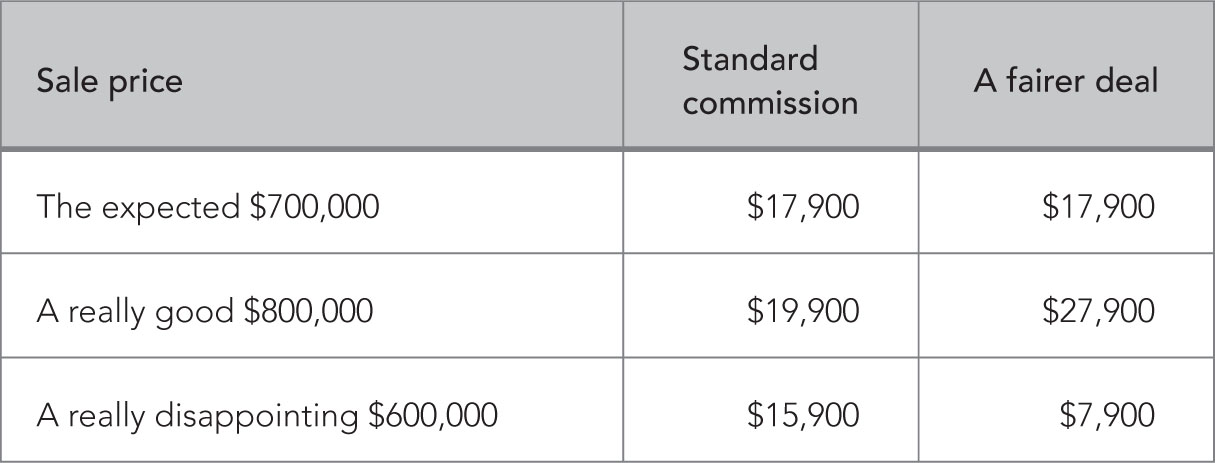

I object to the way most NZ real estate agents structure their commissions. It means that they have little incentive to get the best price for you. But you can always propose a different, fairer structure. An example is probably the best way to show this:

Let’s say you meet with three or four agents to discuss listing your house. Get in writing how much they expect you’ll get for the house. Then ask how their commission is structured.

It will probably be something like: 3.95% of the first $200,000 (which comes to $7,900) plus 2% of the rest. If the expected price is $700,000, the commission would be $7,900 plus $10,000, which is $17,900.

When you’ve chosen your agent, tell them you would like to structure the commission as shown in Figure 18.

By following Figure 18, if they sell at the expected $700,000, they will get the same $17,900.

If they sell for more, for every dollar over $700,000 they get 10% extra. Say they did brilliantly and you sold for $800,000. They would get $17,900 plus 10% of $100,000, which is $10,000. Their total commission would be a fat $27,900. You pay a lot more, but you don’t mind, because you got such a good price.

Under the standard formula they would have got $17,900 plus just 2% of $100,000, which is $2,000 – bringing their total to just $19,900. That’s not much more for them, after they did so well, especially given that part of the agent’s commission goes to their firm. Why would they bother to put much extra effort into getting you a high price?

But if they sell for less than $700,000, for every dollar under that price they get 10% less. Say the sale price ended up being only $600,000. They would get $17,900 minus 10% of the $100,000 shortfall. That’s $17,900 minus $10,000, or just $7,900.

Figure 18: Our example of a fairer deal in real estate commission

Under the standard formula it would have been $17,900 minus $2,000 – a total of $15,900. They did poorly, but they would have got much the same commission as if they had done well.

Point out how much more they will get if they do well for you, while acknowledging that if they do badly they will get a lot less.

Some agents will baulk at this. It’s an interesting test, actually, of how confident they really are that they will get you $700,000. Agents often overestimate the price, in the hope you will list with them.

To encourage them, consider offering a bonus of, say, $1,000 over and above their commission, at whatever price they get. If the agent still won’t go along with it, ask another one you met.

I’ve successfully used this structure twice. Once we sold for way less than we had hoped – and the agent had indicated – but it was some consolation to know we weren’t paying out many thousands for a job poorly done. The other time we sold at about the expected price.

On another occasion, though, none of the agents working in that suburb would go along with my proposal. Collusion? Who knows? It was worth a try.

Other issues when choosing an agent

When you’re discussing commissions with agents, the companies that charge more will tell you that you pay for quality, but I’m not sure that’s necessarily true.

How do you tell quality? Ask the agents for written info on recent houses they have sold, including their price expectations and what they sold the properties for.

Get details on how they plan to market your property, and how much you’ll have to pay for the marketing. Apparently most house buyers these days first spot a property online, so make sure the online marketing is done well – including perhaps Trade Me, Facebook and Google advertising.

Also, of course, ask your friends and neighbours for recommendations. And – importantly – check the public register on the Real Estate Authority website, www.rea.govt.nz, to make sure the agent is licensed. The register will also tell you whether there is any ‘disciplinary history’ over the past three years for that agent – in other words, whether there have been any complaints upheld against them.

It’s not about the car

Some people say you can judge a real estate agent by their car. If it’s expensive, they must be doing well, which suggests they are good at their job. Then again, it might suggest their commissions are too high! Or perhaps they’ve run up a huge debt to buy the flash car. Remember The Millionaire Next Door? Ignore the car, and take note of what they say they will do for you – in writing. Ditto expensive clothes.

Tips for sellers

• Before you even talk to agents, pay for a professional valuation of your property. That gives you power when negotiating with agents or buyers if they’re talking too low a price. It also signals when an agent may be suggesting too high a price when they first meet you.

• While agents are supposed to be getting you the best price, they have a big incentive to sell fast and move on to the next property, especially under the usual commission structure discussed above. Don’t be pressured to accept a low offer, especially early on.

• Usually agents’ contracts are for 60 or 90 days. Go for 60 or perhaps less. If the property hasn’t sold at the end of the contract period, you might want to try a different agent. Take note, though, of a warning from Consumer NZ. Some contracts say you have to pay the first agent if a buyer who saw the property while that agent was listing it comes back and makes an offer via a second agent. You could find yourself paying commissions to both. Don’t sign any contract that requires you to pay a commission once the contract has expired.

• You can renegotiate the agent’s commission at any time. Let’s say a buyer’s final offer is less than you are willing to take. Ask the agent if they will reduce their commission, so you end up with a bit more. They might agree, just to get the sale.

Step ? check

Have you:

![]() Decided whether you want to own a home?

Decided whether you want to own a home?

![]() If yes: thought about options – a boat, a tiny house, buying with friends, being a renter-landlord?

If yes: thought about options – a boat, a tiny house, buying with friends, being a renter-landlord?

![]() Done your homework before buying – see our list?

Done your homework before buying – see our list?

![]() Looked into mortgage choices?

Looked into mortgage choices?

If you already own a home, have you:

![]() Considered changing your mortgage?

Considered changing your mortgage?

![]() Set up a plan to pay off the mortgage faster?

Set up a plan to pay off the mortgage faster?

If you want to sell, have you:

![]() Put effort into making the house look great, picking an agent and negotiating commission?

Put effort into making the house look great, picking an agent and negotiating commission?

Reward

Chocolates, cheese or flowers; or a ‘me day’ with a walk, book, time with family, being creative; or donating to a charity, or anything else that makes you smile.

What’s next? If you want help with your money, let’s get good help.