Victory in the West, 1864

I am bound to say, while I deplore this necessity daily [of laying waste to the countryside of Georgia] and cannot bear to see the soldiers swarm … through fields and yards,—I do believe it is a necessity. Nothing can end this war but some demonstration of their helplessness, and the miserable ability of J. D. [Jefferson Davis] to protect them. … But war is war, and a horrible necessity at best; yet when forced on us as this war is, there is no help but to make it so terrible that when peace comes it will last.

—Henry Hitchcock, Marching with Sherman

One of the truisms of military affairs is that amateurs talk about operations, but professionals about logistics. Over winter 1863/64 Grant and Sherman underlined they were modern professional soldiers, because it was to that dismal subscience of war, namely, logistics, that they devoted themselves. They understood that if they were going to project Union military power into Georgia and on to Atlanta from their main bases at Nashville and Chattanooga, their armies had to have a reliable system of supply. Yet, the campaign against Chattanooga in summer and fall 1863 had rested on railroads verging on collapse, a transportation system, moreover, Confederate guerrillas and raiders had disrupted for significant periods. Thus, the first order of business was to insure the coming Union offensive would possess a logistical system that could support Union armies from Nashville to Chattanooga, and then to Atlanta.

Until mid-March, when he moved east to assume his duties as commander in chief of all Union armies, Grant focused on ensuring that the advance on Atlanta would possess the logistical infrastructure, that is, one dependent on railroads, required to support Union forces deep in the Confederacy. Work began on repairing and building that infrastructure almost as soon as the Confederates had fled Missionary Ridge. The distance over which the logistical system had to work was, according to Sherman, 185 miles from Louisville to Nashville, 151 miles on to Chattanooga, and 137 miles from Chattanooga to Atlanta, a total of 473 miles. The distance between the Franco-German frontier and Paris, over which the Prussian Army had such trouble in supplying its army in 1870–71, is 250 miles, approximately half of what Union logistics had to support during the siege of Atlanta. Moreover, the French road network was of a high class by the standards of the time, while the road network in northern Georgia was virtually nonexistent. Sherman’s engineers also had to maintain the railroad from Chattanooga to Atlanta and then keep it open under incessant attacks.

Sherman’s calculations were that the logistical support necessary to keep his armies in the field required sixteen trains per day pulling a total of 160 cars, which could haul 1,600 tons per day from Nashville to Chattanooga and then on to Atlanta. That effort was sufficient to support his army of 100,000 men and 35,000 animals from 1 May to 12 November 1864. To have had a similar amount of food, ammunition, and forage, according to his calculations, would have required 36,800 wagons, each pulled by six mules, to haul their loads at a rate of twenty miles per day, “a simple impossibility in roads such as then existed in that region of country. Therefore, I reiterate that the Atlanta campaign was an impossibility without these railroads; and only then, because we had the men and means to maintain and defend them, in addition to what were necessary to overcome the enemy.”1 This campaign was war in the industrial age.

There lay the crux of the matter, for it had largely been the result of Grant’s planning and energy that created the means “to maintain and defend” this crucial logistical system. The first element in creating this system lay in the repair of the railroads between Nashville and Chattanooga, as well as creation of subsidiary lines. To further the refurbishment of the system, Grant fired the previous director of the line and initially replaced him with Major General Grenville Dodge. Within forty days Dodge’s XVI Corps had repaired or relaid a hundred miles of track and repaired or rebuilt 182 bridges. In February 1864, Grant appointed Daniel McCallum, one of Herman Haupt’s most competent assistants in running the eastern railroads, as general manager of all military railroads in the West, which consisted of the Southern railroads Union forces controlled.

McCallum created two departments, the first to control rail movements and perform day-to-day repairs. The second department had responsibility for major repair work on bridges and sections damaged or wrecked by Confederate raiders and to build new rail spurs where necessary. This division of responsibility continued through fall 1864. McCallum further divided the construction corps into six separate sections, each with the same organization but responsible for different portions of the line. He also distributed stockpiles of bridging materials, rails, and ties throughout the system, so that his construction divisions possessed the necessary material to carry out major repairs immediately.

Finally, McCallum contracted through Stanton for the purchase of new locomotives and rolling stock from Northern manufacturers. The first twelve new locomotives rolled into Nashville in April, twenty-four more in May, twenty-four in June, and a further twenty-six in July. By year’s end Northern manufacturers had delivered 140 new locomotives to the Western theater, while they also built and delivered an average of 202 new freight cars a month. Nothing better underlines the gap between the resources available to Northern military commanders and those available to the Confederacy, which failed to produce a single locomotive during the entire war.

Unlike current logistical practices in a zone of military operations, in the Civil War civilians ran the locomotives, maintained the roadbeds, and repaired the damage caused by Confederate raiders and guerrillas. Their commitment was extraordinary. As McCallum reported, “it was by no means unusual for men to be out with their trains from five to ten days without sleep, except what could be snatched upon their engines and cars while the same were standing to be loaded or unloaded, with but scanty food, or perhaps no food at all, for days together, while continually occupied in a manner to keep every faculty strained to its utmost.”2 McCallum’s men confronted not only the balky and often dangerous machinery of the time but also the dangers of guerilla attacks or damage to the rails, which often led to disastrous crashes.

There was one other element in the logistical system of critical importance. While his construction troops refurbished the roadbeds, rails, and bridges, Grant, and then Sherman, ordered construction of block houses to protect the most critical bridges. This involved the detailing of significant numbers of soldiers, but here again the North’s manpower advantage told. There were sufficient troops available to protect the logistical infrastructure, while at the same time enabling Sherman to throw a massive military force into Georgia and supply it. That advance to Atlanta would then depend on McCallum’s construction crews rebuilding the roadbed, laying new rails, and constructing new bridges, as Johnston’s soldiers had destroyed everything of use, particularly railroad tracks and bridges, as they retreated south.

Napoleon’s invasion of Russia had failed over distances that were logistically comparable to the task Sherman’s armies faced, if one considers the origin of Union supplies. The French march to Moscow failed because animal muscle power could not sustain logistical support at such distances. Nothing better underlines the fact that the North’s victory depended on the Industrial Revolution to overcome the continental distances of the South than the logistical support rendered by railroads in 1864. What had been logistically impossible before was now possible.

For those who dismiss the idea that the Civil War was a war of the industrial age, it is well to recall that in September 1914 the German advance in France came to a floundering halt as much for a failure of logistical support as for any other reason. As German troops fought a desperate Battle of the Marne for what the German general staff regarded as the decisive campaign of the war, the German army had barely repaired the railroads through to Brussels. While the Germans kept their troops supplied by living off the countryside of Belgium and northern France at the height of the harvest season, such was the state of their supply system in early September that some troop commanders took the dubious expedient of feeding their troops wine and champagne to keep them going. Admittedly, Grant and Sherman had been at war for three years in dealing with the problems of projecting military forces over great distances. Nevertheless, the care with which they prepared the logistical base for the 1864 campaign in the West stands in stark contrast with the lack of preparations made by the Germans in either 1870 or 1914.

The Opponents

On 18 March, Sherman assumed command of the Military Division of the Mississippi from Grant. By this point the gathering of supplies and troops at Nashville and Chattanooga for the campaign against Atlanta was in full swing. Grant fully trusted Sherman, and despite the latter’s plea that the new commander in chief of Union armies remain in the West, Grant determined that he needed to go east and supervise the Army of the Potomac. He had no qualms about leaving Sherman in charge of what turned out to be the war’s decisive campaign—one that would insure Lincoln’s reelection and break the Confederacy’s will. Sherman, while still displaying the restlessness that had led to his near breakdown in 1861, had now brought a discipline and focus to his energy. Grant’s trust, as well as Sherman’s experience in the field, provided Sherman with the confidence in his abilities necessary to master the uncertainties, ambiguities, and doubts that confront all those in independent command.

Sherman also had an important advantage over Grant in the 1864 campaigns: he knew and trusted his subordinates, who were for the most part outstanding combat leaders in their own right. They were generals who had grown under Grant’s mentorship, and they reflected an organizational culture that emphasized leadership, initiative, and drive. Some historians have ascribed the culture of the Western armies to the peculiarities of soldiers brought up in the hard life of turning a wilderness into civilization. While there may be some truth in that argument, the Confederate Army of Tennessee, an army consisting wholly of westerners, displayed few of the qualities of its Union opponents. Instead, like the Army of the Potomac, it stood the course in spite of an appalling series of defeats.

Sherman divided his forces into three separate “armies,” which differed in size. Each possessed differing subcultures, reflecting their origins and the nature of their commanders, who had led them during the war. Each army was capable of acting independently, which provided Sherman greater flexibility than was the case with the Army of the Potomac’s rigid structure, while their varying sizes allowed him the flexibility to tailor the army to the task at hand. In effect, Sherman led what we would today term an army group.

Major General George “Pap” Thomas, who had won fame for fending off the Confederates at Chickamauga, commanded the largest of Sherman’s armies, the Army of the Cumberland. A native Virginian, Thomas had kept his oath to defend the Constitution. After his soldiers had seized Missionary Ridge in the Battle of Chattanooga, a chaplain, charged with laying out the Union cemetery, had asked whether he should have the Union dead buried by states. Thomas replied that they should bury them together, as the division of states had already caused too much trouble. As a commander, Thomas was steady, rather than brilliant, but when he acted, he acted with thoroughness. There was a native caution to his nature, but he held none of the mindless fears that had characterized McClellan. His troops loved him, perhaps because they sensed that he was cautious with their lives. Altogether his army numbered 60,773 (54,568 infantry, 2,337 artillery, and 3,828 cavalry) with 130 cannons. The army was divided into three corps: the IV under O. O. Howard; the XIV under John Palmer; and the XX (a combination of the XI and XII Corps which had come west in fall 1863) under “Fighting Joe” Hooker.

Major General James McPherson led Grant’s and Sherman’s old army, the Army of the Tennessee. McPherson was new to command and young for his position. He had graduated first in his class from West Point in 1853 along with Sheridan and Hood. Both Sherman and Grant regarded him almost as a son, but his rise to the top reflected considerable military abilities. Like many other successful Civil War generals, McPherson grew into higher position as the war progressed, but from the beginning he had displayed outstanding leadership qualities. Like Thomas, his troops held him in high regard. Attrition and the transfer of some of its divisions to other armies had decreased the Army of the Tennessee from the force Grant had led against Vicksburg. Nevertheless, it was a veteran force with high morale consisting of 24,465 soldiers (22,437 infantry, 1,404 artillery, and 624 cavalry) with ninety-six guns. These were divided into three corps: the XV under “Black Jack” Logan, an Illinois politician of considerable military competence; the XVI under Major General Grenville Dodge; and the XVII under Major General Francis P. Blair Jr. Logan was one of the most outstanding combat commanders of the war, so highly thought of by Grant that he almost became Thomas’s replacement at the end of 1864.

The smallest of the armies was that of the Army of the Ohio under Major General John Schofield. Nevertheless, there were times when Sherman detached corps or divisions from other armies and assigned them to Schofield, who had graduated from West Point in 1853. The outbreak of the Civil War had found him on a leave of absence from the army and teaching physics at Washington University in St. Louis. He became Nathaniel Lyon’s chief of staff in the desperate effort to keep Missouri in the Union and was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his bravery at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in August 1861. After extensive service west of the Mississippi, Schofield received command of the Army of the Ohio, which to all intents and purposes was a fleeted-up corps, consisting of 13,559 soldiers (11,183 infantry, 679 artillery, and 1,697 cavalry) with twenty-eight guns. The army possessed one corps under Schofield’s command, but also George Stoneman’s (another reject from the Army of the Potomac) cavalry division.

Opposed to Sherman was the Army of Tennessee, which Johnston had assumed command of after Bragg’s disastrous defeat at Chattanooga. Davis, given the deep antipathy between himself and the general, had not wanted to appoint Johnston, but there was no other choice, since he disliked Beauregard even more. Johnston found the Army of Tennessee in disarray, because Bragg was not only a bad tactician, but a weak administrator. Thus, throughout the winter Johnston confronted much the same task that Hooker in early 1863 had confronted in repairing the administrative and logistical damage his predecessor had caused. To the extent possible, given the shambles which passed for the Confederacy’s logistics, Johnston attempted to feed, clothe, and equip the Army of Tennessee adequately. With a lighter hand than Bragg, Johnston restored discipline. He also had charismatic rapport with the soldiers that went beyond simply not being Bragg. By spring he had restored the army’s morale.

Johnston’s approach to the war was quite different from that of other senior Confederate commanders, for he had the least desire to seek battle for its own sake. There are two possible explanations. The first appears in an entry in 1861 in Mary Chesnut’s deliciously sharp diary. She records a story told by one of her male friends about Johnston that underlines Confederate suspicions about the general’s willingness to get into a scrap: “Wade Hampton brought him [Johnston] here to hunt. … We all liked him—but as to hunting, there he made a dead failure. He was a capital shot, better than Wade or I and we are not so bad—that you’ll allow. But then with … Johnston the bird flew too high or too low—the dogs were too far or too near–things never did suit exactly. He was too fussy, too hard to please, too cautious, too much afraid to miss and risk his fine reputation as a fine shot. … Unless his ways have changed, he will never fight a battle—you’ll see. Oh, yes—he is as brave as Caesar. An accomplished soldier? Yes, who denies it? You’ll see. … [Nevertheless, in war] he is too particular—things are never all straight. You must go at it rash—at a venture to win.”3

That mentality was precisely the great flaw in the Confederate approach to the war: the desire to attack, attack, and attack with resulting casualty bills that eventually broke the will of the Confederate people. It may be that Johnston was just too fussy about finding the perfect circumstances. Or like Porter Alexander and many modern historians, he believed the Confederacy could not afford the heavy casualties involved in an aggressive approach and that a Fabian strategy aiming at exhausting the North’s will was the only route to success—despite the aggressive inclinations of Confederate public opinion. Either explanation helps explain Johnston’s generalship, which came close in 1864 to preventing Sherman from capturing Atlanta.

For Johnston the improvement of the army’s morale and discipline proved to be the least of his problems. The repair of the command relations among the fractious corps and division commanders proved an insurmountable task. The dysfunctional command culture had been a direct result of Bragg’s leadership; about the only thing his subordinates could agree on had been that Bragg must go, but the various plots and efforts to remove Bragg had engendered a climate of suspicion and a lack of loyalty among the senior officers. Not surprisingly, the command climate ended up in poisoning their relations with their new commander as well as among them. Throughout spring 1864, Johnston’s corps commanders consistently attempted to undercut their commander’s position by reporting maliciously and dishonestly on the army’s combat capabilities to politicians in Richmond, including Davis. Admittedly, Johnston did not help matters by the fact that he failed to share his plans and conceptions with his senior generals. Part of the reason may well have been that he caught a sense of the poisonous atmosphere among his senior subordinates. As he noted when he assumed command: “If I were president, I’d distribute the generals of this army over the Confederacy.”4

Exacerbating the poisonous command climate was the fact that the arguments and disagreements between Bragg and his generals had spilled over into the political arena. During Bragg’s tenure as commander of the Army of Tennessee, disgruntled generals had taken to writing their political friends in Richmond, including the president. None of that changed with his relief. Johnston, himself, had played the political game by using surrogates, such as Senator Louis Wigfall, to argue his case, particularly in regard to the Vicksburg campaign. Given Davis’s personality and his suspicion of others, except the few he regarded as friends, the result was a deeply fractured relationship among Confederate generals in the West. In such a climate, it was impossible to develop an effective strategy for the 1864 campaign. Adding to the fractiousness of relations among the senior officers was the fact that in January 1864, Patrick Cleburne, former British Army sergeant and outstanding division commander, had proposed enlisting slaves in Confederate armies in return for their freedom. That proposal caused a furor about an abolitionist conspiracy that spread from the senior ranks of the Army of Tennessee to Richmond before Sherman’s offensive provided other matters on which the generals could focus.

The appointment of Hood to a corps command in the army only made matters worse. Hood had spent fall and winter 1863/64 in Richmond recovering from the amputation of his leg from a wound suffered at Chickamauga, not to mention an arm so badly injured at Gettysburg as to be largely useless. In the Confederate capital he found himself lionized. Hood enthusiastically courted the president and his wife, Varina, in whose house he became a fixture. Undoubtedly, he was a brave and outstanding division commander, but he had not a clue about strategy, logistics, or operations. Moreover, his physical condition was serious; he could not mount a horse without help, and once on horseback had to be tied to the saddle. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, he was deeply ambitious, ambition fueled by his physical condition. Upon arrival in Dalton, he began writing Davis a stream of letters, all of which confirmed the president’s unrealistic hopes that the Army of Tennessee was in the position to launch a major offensive to regain Tennessee. Johnston never caught on to the duplicitous role that Hood was playing. Instead, he regarded him as his most loyal corps commander.

Even before the winter ended, Johnston found himself under pressure from Davis to attack Union forces in Chattanooga and continue on to regain central Tennessee. Hardee had assumed acting command of the army after Bragg’s resignation, and astonishingly he had sent Richmond a series of reports indicating the army had rapidly recovered from its defeat. As he turned the army over to Johnston “with great pleasure,” he reported it in “fine condition.”5 It was not; it was a broken and fragile instrument. From Hardee’s reports, Davis gained an impression that remained with him into the spring. As a result, he bombarded Johnston with proposals of the most unrealistic kind, including one for the army to invade southern Tennessee, in spite of its deplorable state and lack of a supply system to support such a move in the dead of winter. Moreover, such an offensive would have advanced through one of the poorest areas in the South, one consisting of rugged mountains with a few hardscrabble farms the opposing armies had already picked clean. That landscape was one that could hardly supply a brigade much less an army, unless, of course, there was a logistical system capable of supplying the army’s needs.

Davis’s missives, urging an offensive into Tennessee, received support not only from Bragg but from Lee as well. Bragg, continuing his contributions to the Confederacy’s defeat, was now serving as Davis’s chief military advisor and delighted in the opportunity to inform the president that the Army of Tennessee was in excellent shape for a drive to recapture Tennessee. Bragg, of course, should have known the state in which he had left his army, but military reality had never interfered with his capacity for intrigue and back stabbing or for that matter in currying favor with the president. Bragg did this despite the fact he had rejected many of those proposals for offensive operations in southeastern and eastern Tennessee when he had commanded the Army of Tennessee, and it had been summertime.

Not until late March did a series of reports, authored by Davis’s own representatives, reach Richmond on the real state of the army, particularly in regard to its shortages in artillery, horses, and mules. But none of these made an impression on Davis, who had made up his mind that Johnston possessed the means to attack Grant and Sherman and was obdurately refusing the sensible advice from Richmond. Contributing to Davis’s refusal to recognize reality were the reports Hood was enthusiastically writing about the army’s state and Johnston’s refusal to take the offensive, which Hood deeply regretted, “as my heart was fixed upon our going to the front and regaining Tennessee and Kentucky.”6 The result of Davis’s misapprehensions was simple. Because it was politically impossible for him to fire Johnston, he took the disastrous course of refusing reinforcements.

Lee exacerbated Davis’s inclinations by arguing that the buildup of Union forces along the Rappahannock River was the result of the transfer of forces from Tennessee. He urged an aggressive move north by the Army of Tennessee to take the pressure off the Army of Northern Virginia. In the face of Lee’s arguments, Johnston reported to Richmond the hard reality that Sherman’s forces had not diminished in size, but instead were steadily growing. What Lee and Davis failed to recognize was that while there was a major Union buildup occurring in northern Virginia, a similar buildup was occurring in Tennessee as well, as the North, now mobilized, could concentrate overwhelming force not only on two major drives but also on subsidiary offensives. By April the evidence of the Northern buildup in the West was there for all to see. In addition, Lee obviously had no comprehension of the logistical difficulties confronting the Confederates in the Western theater. Perhaps considering the Confederacy’s shortages in men and resources in 1864, it is understandable its leaders failed to grasp the extent of the military forces the North was gathering.

Quite simply, Johnston did the only thing he could, which was to remain on the defensive and await Sherman’s offensive. He had two infantry and one cavalry corps under his immediate command at Dalton: Lieutenant General William Hardee’s corps with divisions under the command of Major Generals Benjamin Cheatham, Patrick Cleburne, William Walker, and William Bate; and Hood’s corps with divisions under Major Generals Thomas Hindman, Carter Stevenson, and Alexander Stevenson. Polk’s corps was in Alabama to protect Mobile against a potential Union attack on that port, and there it would have remained had not Banks completely floundered in the Red River’s mud. Polk’s corps would return to Johnston’s command at a key point in the campaign. There was one major flaw in Confederate dispositions. Davis and Bragg posted Forrest out in western Mississippi to execute a raiding strategy to carry the war into western Tennessee and along the Mississippi. It was one more indication of Davis’s strategy of attempting to strike everywhere rather than focusing on the theater that mattered. As for Bragg, he undoubtedly was paying Forrest back for the furious tirade Forrest had launched at him in his departure from the Army of Tennessee in late 1863.

Forrest’s assignment to Mississippi left Johnston with Wheeler to command his cavalry; and while that officer was an outstanding combat commander, he possessed none of Stuart’s or Forrest’s ability to ferret out the enemy’s moves and strike where it mattered. As one commentator noted after the war, “he’ll fight; game as a pebble is Wheeler. But there’s one trouble with Wheeler’s valor. It overruns itself. He’ll fight flies as ferociously as he has Spaniards.”7 With only 41,300 infantry available for defense of north Georgia, Johnston stood in danger of being overwhelmed by Sherman’s armies, numbering over 100,000 tough, experienced soldiers.

In terms of campaign planning, neither Sherman nor Johnston possessed the immense staffs characterizing military organizations in the twentieth century. The search for Sherman’s or Johnston’s detailed plans represents an anachronistic search for what never existed. Like Moltke the Elder after the Franco-Prussian War, both generals understood instinctively that plans never survive first contact with the enemy, because the enemy gets a vote. The enemy will always do the unexpected, while a cloud of uncertainty and ambiguity enshrouds the conduct of operations. Both generals undoubtedly held conceptions of how they hoped their military efforts would unfold. Given the expanse of the theater, Sherman aimed to use his superior numbers to outflank the Confederates from their strong defensive positions and hopefully catch them in unfavorable tactical deployments where he could destroy them. For his part, Johnston aimed at conducting a cautious campaign that recognized the disparity in numbers; he too intended to look for favorable moments when he might catch Sherman’s forces divided and vulnerable to a riposte.

Making the task of offensive operations more difficult was the fact that both armies, like those in the East, understood the importance of entrenching themselves as quickly as possible, when they came in contact with the enemy. In several cases during the campaign, units even entrenched when they were actually under attack. For Sherman, this meant a war not only of operational movement, but also of tactical defense. Thus, in a tactical sense the war in the West was one dominated by the defense, although on the strategic level it was a war of movement, where Sherman’s numbers provided him a distinct advantage.

The Atlanta Campaign

Concurrent with the Army of the Potomac’s move into the Wilderness, Sherman arrived at Ringgold, Georgia, on 5 May, and his troops immediately began their drive south. One of the officers, formerly of the XII Corps, which had now been amalgamated with the XI to form the XX Corps, described Sherman in the following terms: “Sherman could be easily approached by any of his soldiers, but no one could venture to be familiar. His uniform coat, usually wide open at the throat, displayed a not very military black cravat and linen collar, and he generally wore low shoes and one spur. On the march he road with each column in turn, and often with no larger escort than a single staff-officer and an orderly. In passing us on the march he acknowledged our salutations as if he knew us all, but hadn’t time to stop.”8

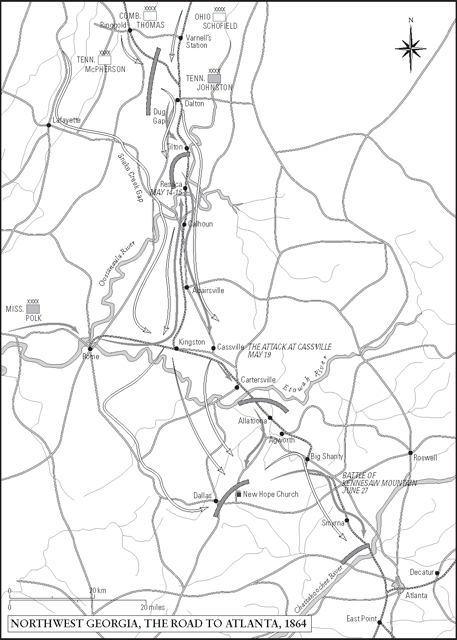

The difference between the theater of operations from that of the East was that Sherman had greater room for maneuver. At the campaign’s start, Johnston’s left flank rested along Rocky Face Ridge, which ran just to the west of Dalton from north to south. There were several gaps through the ridge, but Johnston had them covered. However, he believed Sherman would not attempt to outflank him to the west, but would drive east of Rocky Face Ridge, where the Confederates were best placed to meet his forces. As a growing number of reports indicated Sherman’s armies were on the move, Johnston requested aid from Polk, whose corps had remained in southern Alabama to defend Mobile. Richmond agreed to the movement of a single division, but instead Polk moved his entire force of 10,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry to aid Johnston—a move that proved crucial to Johnston’s ability to fend Sherman off, but one that outraged Bragg. Thus, Polk provided Johnston with a third corps, which would not have been available, had Halleck seen the importance of Mobile and had Banks been where Grant had intended him to be. As they had done in April 1862, the Confederates concentrated in the West by taking risks in other areas.

But Sherman had no intention of attacking into the teeth of Confederate defenses. While Hooker probed various gaps in the Rocky Face Ridge and Thomas threatened Johnston’s Dalton position from the north, McPherson with the Army of the Tennessee executed a wide swing to the west and an advance that carried his troops to Snake Creek Gap. Johnston picked up little of what Sherman was doing, largely as a result of the fact that Wheeler’s cavalry failed to win the fight for information. Confederate cavalry commanders in the West excelled in fighting, like Stuart, but unlike Stuart, they were terrible at gathering intelligence. What became clear at once was the fact that Union soldiers were probing Johnston’s left flank west of Rocky Face Ridge for weaknesses in his defenses guarding the gaps through the ridge. On 8 May Hooker’s XX Corps hit Dug Gap with a major blow, which the Confederates were barely able to counter by the arrival of two brigades from Cleburne’s division.

But on the 8th a more dangerous situation appeared. McPherson and the Army of the Tennessee were moving steadily toward Snake Creek Gap five miles to the south. Wheeler failed to pick up this move because he had disobeyed his orders. Instead of covering the area west of Rocky Face Ridge and the approaches to the gaps, Wheeler wasted his time in skirmishing with Union cavalry. Not until early on 9 May did the Confederates discover that McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee with over 20,000 men was approaching Resaca, the capture of which would have cut Johnston’s lines of communications with Atlanta and placed McPherson in his rear. While the defenses of Resaca appeared formidable, there were only 4,000 soldiers manning them. Finally awakening to the danger, Johnston ordered a portion of Hood’s corps south, but it would have arrived too late, had McPherson attacked. He did not, because the entrenchments appeared too formidable. The Army of the Tennessee then pulled back to Snake Creek Gap. Sherman’s laconic comment in his memoirs on the episode was that “such an opportunity does not occur twice in a life.”9

Sherman then pulled the full weight of his force down the valley to the west of Rocky Face Ridge in a move to assault Resaca with overwhelming force. Yet, by the time Thomas’s divisions had linked up with McPherson west of Resaca, it was too late. By 13 May Johnston had awoken to the danger and pulled out of Dalton. Thus, the Army of Tennessee, including most of Polk’s troops, concentrated on Resaca. Combined with the positions surrounding the town, they made Resaca too formidable to risk assault. Sherman’s armies then continued their outflanking move to the west and south. Union engineers threw pontoon bridges across the Oostanaula River, and advance units placed Sherman in position to attack Johnston’s rail communications. That ended Confederate hopes of attacking Sherman’s eastern flank with Hood’s corps, although one of Hood’s divisions failed to receive the word to pull back, attacked entrenched Union troops, and suffered heavy casualties. Johnston ordered his army to abandon Resaca and retreat. Round one had gone to Sherman. Moreover, he had served in northern Georgia as a lieutenant in the 1840s and knew the countryside well.

There was no terrain south of the Oostanaula on which Johnston could develop defensive positions to stop Sherman until the Army of Tennessee reached Kingston. As the three arms of Sherman’s army group advanced southward, Schofield, reinforced by Hooker, moved toward Kingston on both sides of the Western & Atlantic Railroad. Sherman detached two cavalry and an infantry division to wreck the Confederate industrial center at Rome. Rome fell on 18 May, as the rest of the Union armies drew closer to Kingston. As the march continued, Sherman’s construction crews repaired the captured railroad almost as fast as the troops advanced. When Union troops found the bridge across the Oostanaula destroyed, Sherman ordered his chief construction engineer, General William Wright, to rebuild it in two days. It took Wright and his construction crew of 2,000 men three days. As Wright described it: “the work of reconstruction commenced while the old bridge was still burning, and was somewhat delayed because the iron rods were so hot that the men could not handle them to remove the wreck.”10

By the time the Western armies arrived in front of Kingston, halfway between Ringgold and Atlanta, they had suffered only 4,000 casualties, only slightly more than the Confederates. For his part, Johnston had prepared an ambush by deploying Polk’s and Hood’s corps east of the Kingston-Cassville line, while Hardee pulled back to the line between those two towns. The aim was to smash Schofield’s reinforced Army of the Ohio before Thomas could arrive. Johnston was so enamored of the opportunity that he issued an order of the day to the troops, who responded with considerable enthusiasm for the opportunity to attack. However, Hood, supposedly the spearhead, failed to attack because a report indicated Union troops were outflanking his corps to the east. In fact, a small Union force had taken a wrong turn and simply wandered into Hood’s rear. Alarmed by a threat to his rear, but failing to order a more thorough reconnaissance, Hood called off the attack and retreated. Johnston confirmed Hood’s decision without checking on the situation despite Hood’s inexperience.

The Confederates fell back on the ridge line that ran from east to west behind Cassville. Johnston believed it to be a strong position, but neither Hood nor Polk liked it. In a conference over the evening and night of 19/20 May, the two corps commanders talked Johnston out of defending the position, Hood even claiming the Confederates could not hold the position for two hours. The Confederates retreated across the Etowah River into a strong position at Allatoona. But Sherman had no intention of dancing to Johnston’s tune. Instead, he ordered each of his three armies to draw rations for twenty days and set them in motion to cross the Etowah far downstream, Schofield crossing ten miles west of Allatoona, while Thomas and McPherson crossed even farther west. Johnston had no choice but to authorize a retreat from the Allatoona position along the railroad to the southeast, the Army of Tennessee taking up positions near New Hope Church. There the lead division of Hooker’s corps, commanded by Brigadier General John Geary, former governor of the Kansas territory under Buchanan, ran into Hood’s soldiers near New Hope Church. Hooker’s soldiers received a nasty rebuff that cost them 1,665 casualties.

Two days later, on 27 May, Sherman launched another probing attack on Johnston’s line, this one by Howard, but one no more successful. A Confederate probing attack on McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee at the western portion of Sherman’s line also suffered a bloody repulse. At an afternoon conference on 28 May, Hood proposed that his corps pull out of the line and launch a flank attack on the eastern side of Union lines. Johnston approved, but when Hood deployed to attack, he discovered Union commanders had stationed a division guarding their flank in another heavily fortified position. There was no opportunity to launch a Chancellorsville-style attack. Again Hood used his latitude and called off the attack. Nevertheless, in spite of his own unwillingness to attack on several occasions, Hood continued to write Davis that Johnston was failing to use the Army of Tennessee offensively.

Threatened by Sherman’s outflanking movements, Johnston ordered another retreat. Despite almost continuous rain, Sherman’s troops had reached Big Shanty, halfway between Allatoona and Marietta, by 6 June. Within five days Wright had rebuilt the railroad to Big Shanty, and the flow of supplies continued. In addition, 10,000 of Blair’s XVII Corps soldiers returned to McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee, the men having completed their reenlistment furloughs. They more than made up for Sherman’s losses thus far in the campaign. Nevertheless, Sherman was not happy with the performance of his subordinates. His major criticism was of Thomas. He wrote Grant that “my chief source of trouble is with the Army of the Cumberland, which is dreadfully slow. A fresh furrow in a plowed field will stop the whole column, and all begin to intrench [sic]. I have again and again tried to impress on Thomas that we must assail and not defend … and yet it seems the whole Army of the Cumberland is so habituated to be on the defensive that, from its commander down to the lowest private, I cannot get it out of their heads.”11 Sherman’s impatience undoubtedly helps explain why he was about to make the biggest mistake of the campaign.

Meanwhile, Johnston had had his engineers lay out new and impressive defensive positions. These rested on Kennesaw Mountain with Brush Mountain covered by cavalry to the northeast and Confederate lines swinging to the southwest. Out in front beyond the main positions, the Confederates held a small hillock named Pine Top that provided an excellent view of Sherman’s three armies to the northwest. Urged by Hardee to pull the brigade back because Pine Top was too vulnerable to a Union assault, Johnston decided to reconnoiter the position. He, Hardee, and Polk rode to the top, where they dismounted despite warnings of Yankee shelling. At that same moment, Sherman, riding Union lines, saw the group on Pine Top, and, while not recognizing them, but recognizing the uniforms of high-ranking officers, suggested to Howard that his artillery throw a few shells at the Confederate generals. Howard complied, and an Ohio artillery battery hit Polk straight on, splitting the Episcopal bishop nearly in half and thereby removing one of the less effective corps commanders from the Army of Tennessee’s order of battle.

Pulling back from Pine Top, and thus shortening his lines, Polk’s corps, now under its senior division commander, Loring, held the right along Kennesaw Mountain, Hardee the center, and Hood the left. Confederate positions also covered Marietta, with its factories, one of the several important industrial centers in northern Georgia. For reasons that remain unclear, Sherman believed the Army of Tennessee’s center was weak, and on 27 June he launched an all-out assault on Confederate positions, which were not only well entrenched but also strongly held. The results were a disaster. Sherman considered renewing the assault after the first failure, but Thomas persuaded him that further attacks made no sense. Union casualties were over 3,000 compared to barely 1,000 on the Confederate side. However, the day was not an entire failure, because Schofield’s Army of the Ohio, only making a demonstration to hold the Confederates west of the battlefield, managed to cross Olley’s Creek within five miles of the Chattahoochee River, the last major river between Sherman and Atlanta. It was the second success Schofield had gained against Hood in a week; earlier in the week the latter had launched an ill-considered attack without reconnaissance against Schofield’s well-entrenched troops and suffered 1, 000 casualties.

Sherman would not make the Kennesaw Mountain mistake again. Instead, he feinted a move to his left (the east) and moved west. He again loaded up his supply wagons to cut his armies loose. Thomas opposed the move, but after considering the alternatives noted to his commander that, “I think [such a move] decidedly better than butting against breastworks twelve feet thick and strongly abatised.”12 Leaving a strong force of cavalry with their Spencers to cover the railroad, Sherman moved west to outflank the outnumbered Confederates. Once Union troops were across the river, Johnston hurriedly pulled back, and Marietta fell into Union hands. Not surprisingly, Wright’s construction crews soon had the railroad rebuilt all the way to Marietta, and supplies flowed unabated to Sherman’s troops.

But even more important was the fact that Johnston had no choice, but to fall back on Atlanta and its defenses, such as they were. Johnston’s failure to launch a major assault on Sherman’s forces during the course of the two-month campaign had come home to roost. From our perspective, the only major error had come in the failure to attack Schofield in the flank at Cassville. It had been Hood who had blown the chance, but Johnston too was at fault for not having checked up on his subordinate. Yet, given the numbers and the competence of Union commanders, it was inevitable that Sherman and his armies would reach the environs of Atlanta. The mark of Johnston’s generalship lay in the fact that he fended off Sherman’s flanking moves and kept his army intact. In effect, he was prolonging the war, and after the failure of Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania in 1863, a Fabian strategy presented the only possibility for the Confederates to gain their independence. The looming fall presidential election in the North was the last remaining possibility for the Confederacy to survive, and the longer Johnston could draw out the campaign in Georgia, the more doubtful Lincoln’s prospects would become.

But that was not good enough for Davis. Despite the fact that Lee had failed to gain a decisive victory over Grant’s and Meade’s advance, Davis clearly expected something along those lines from Confederate armies in Georgia. Further exacerbating the Confederate president’s anger was the flow of reports from those, like Hood, who were dissatisfied with Johnston’s failure to show the requisite aggressive style of leadership they believed the Confederacy’s situation demanded. Adding to Johnston’s problems was the fact that the Confederacy’s politicians and newspapers were acting in an even more irresponsible fashion than their Northern cousins. The cry throughout the Confederacy was for action to defeat the Northern vandals.

The final nail in Johnston’s coffin came with Braxton Bragg’s visit to the Army of Tennessee. On 9 July Davis dispatched his chief military adviser to Atlanta to scope out the lay of the strategic land. Bragg was the last person Davis should have chosen. The general had regarded his relief after the Chattanooga defeat as the result of a cabal of disgruntled generals who had consistently failed him and who had combined with politicians to cause his downfall. Astonishingly, Bragg believed he had been popular with the troops. He also felt the defeat at Chattanooga was not his fault, but rather the fault of the troops who had refused to do their duty. Now as Davis’s military adviser, Bragg arrived at Johnston’s headquarters to examine the situation in front of Atlanta. Supposedly having done that, which largely involved listening to Hood’s poison, Bragg telegraphed to Davis that “as far as I can learn we do not propose any offensive operations,” despite being briefed on Johnston’s plan to attack Union forces as they crossed Peachtree Creek.13

Hood delightedly bolstered Bragg’s case against Johnston by accusing his commander of failing “to give battle to the enemy many miles north of our present position.”14 Not surprisingly Hood failed to mention those cases where he himself had not attacked. Finally, Bragg added that Sherman had only 65,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry instead of the 100,000 Johnston had more accurately estimated his opponent to possess. Bragg’s advice persuaded Davis to remove Johnston. The choice of his replacement quickly narrowed to a few senior officers. It was obviously not going to be Beauregard, given Davis’s dislike for the creole; Davis probably would have preferred Bragg, but recognized that such a choice would have been disastrous politically; while Hardee had declined the position after Chattanooga. Thus, by default it came to Hood, a general who was the aggressive commander the president and the white South so fervently wanted. Lee, who, whatever his defects as a strategist, was an outstanding judge of military talent, commented on Davis’s decision to appoint Hood to command the Army of Tennessee: “It is a bad time to release [relieve] the commander of an army situated as that of Tenne. We may lose Atlanta and the army too. Hood is a bold fighter. I am doubtful as to other qualities necessary.”15

Lee was right. But Davis had made up his mind. At 2200 on the night of 17 July, Johnston received the telegram announcing the termination of his command and replacement by Hood. It could not have been more curt: “I am directed by the Secretary of War to inform you that as you have failed to arrest the advance of the enemy to the vicinity of Atlanta, far in the interior of Georgia, and express no confidence that you can defeat or repel him, you are hereby relieved from the command of the Army of Tennessee.”16 One corporal in the Army of Tennessee caught the soldiers’ attitude toward the relief: “Old Joe Johnston had taken command of the Army of Tennessee when it was crushed and broken, at a time when no other man on earth could have united it. He found it in rags and tatters, hungry and heart-broken, the morale of the men gone, their manhood vanished to the winds, their pride a thing of the past. Through his instrumentality and skillful manipulation, all these had been restored.”17

Not surprisingly, Sherman and his senior officers were delighted. McPherson and Schofield had been Hood’s classmate at West Point. McPherson’s tutoring of Hood had kept the future Confederate general from flunking out of the academy. George “Pap” Thomas had served in Texas with Hood in the 1850s. All three informed their commander that Hood was reckless and aggressive and that they would soon have a fight on their hands. Sherman later recalled: “At this critical moment the Confederate government rendered us most valuable service. … The character of a leader is a large factor in the game of war, and I confess I was pleased at this change.”18

The Siege of Atlanta

With Hood’s appointment, the period of maneuvering ended and a time of fierce fighting ensued. Hood described himself as cut from the Jackson-Lee mold, but where the former two had a deep perception of the enemy’s strengths and weaknesses, Hood had none. He was still living in 1862 when at Antietam armies had stood toe to toe, fought in the open without entrenchments in receiving enemy attacks, and attempted to overwhelm their opponents with their fury, as if firepower did not matter. Hood’s personality hardly suited him for high command. He had been dishonest in his relationship with Johnston, had lied to Richmond about the condition of the army throughout the spring, and was to blame others for his mistakes throughout his career in the West. None of those qualities endeared him to subordinates, especially since most were older than he. Moreover, as with too many generals in World War I, Hood calculated military effectiveness in terms of the casualties suffered by the units under his command.

As the Confederate high command changed, Sherman continued his wheel to the left toward the east with the aim of cutting the railroad connecting Atlanta to the eastern Confederate states. McPherson led the advance with Schofield and Thomas following. Hood’s first attack came boiling out of Atlanta with the aim of hitting the Army of the Cumberland before Thomas could get his whole force across Peachtree Creek. Alexander P. Stewart’s (Polk’s replacement) corps and Hardee’s corps achieved a degree of surprise, but the Union soldiers had already begun entrenching, when the Confederates attacked. With bare equality in numbers to Thomas, the Confederates had little chance of achieving anything, but they certainly proved they could die in large numbers. Hood blamed Hardee for the defeat. In total, Confederate casualties came close to 5,000, while the Army of the Cumberland barely lost 1,000 killed or wounded.

On 22 July Hood launched his second attack. He chose Hardee to lead the sortie. This time Hood came up with a more imaginative plan than a straightforward lunge. He seems to have hoped to replicate Lee and Jackson’s attack at Chancellorsville. During the day Hood pulled Stewart’s and Hardee’s troops back from Peachtree Creek to the defenses the Confederates were developing on Atlanta’s outskirts. After completion of that move Hardee’s corps was to move out of the line, march through Atlanta to the city’s south, and then swing east and north to catch the Army of the Tennessee in the flank and roll it up. Accompanying Hardee’s flanking march was Wheeler’s cavalry, which was to attack McPherson’s supply train in the rear at Decatur. At the same time Hardee was striking the Army of the Tennessee in the flank, the Confederates manning the fortifications would attack Thomas and Schofield to prevent them from reinforcing McPherson. The attack was supposed to start early in the morning, but a series of delays slowed Hardee’s march and deployment. Thus, his corps was not ready to launch its attack until midday. Moreover, his troops had had no rest, were already exhausted by the heat, and had had little to eat during their march to their jump off positions.

When the attack finally began, Hardee had placed his corps to take the Army of the Tennessee in the flank. But again chance intervened. McPherson had detached Dodge’s XVI Corps on Sherman’s orders to rip up the railroad from Decatur to Atlanta, or at least as close to the city as they could. Dodge’s two divisions were on their way back and, thus, were in position to cover McPherson’s flank when the Confederates attacked. Moreover, they had sufficient time to form into line of battle. As a result, when the Confederate columns broke into the open after floundering through the woods, they had little chance of success, as an aide to McPherson recalled: “It seemed impossible, however, for the enemy to face the sweeping deadly fire from Fuller’s and Sweeny’s divisions, and the guns of the Fourteenth Ohio and Welker’s batteries of the Sixteenth Corps fairly mowed great swaths in the advancing [rebel] columns.”19 There was, however, a dangerous gap between the XVI Corps and the remainder of the Army of the Tennessee. It was into this gap that McPherson rode from a conference with Sherman only to run into Confederates and to be shot dead, when he refused to surrender. With McPherson down, Major General “Black Jack” Logan assumed command of the Army of the Tennessee. It was to be his finest hour, for while the XVI Corps easily handled the attack on the army’s flank, the XVII Corps on the line facing Atlanta was soon in serious trouble from Pat Cleburne’s division, which caught Blair’s corps flush in the flank and caused a desperate retreat by some.

But these were stout veterans, and they put up serious resistance. In one case an officer observed Union infantry make themselves a palisade in the midst of a fierce firefight: “Some distance to the rear of us was a rail fence. Consternation, I have been told, fell upon General Sherman, as with his glass he saw half of Leggett’s division drop their guns and run to the rear. But when he saw them stop at the rail fence, and each man of them pick up two, three, and even four rails, and turn back, carrying them to the place where they had left their guns, he understood what it meant. … The operation was repeated, the rails were placed lengthways along their front; with bayonets, knives, and tin plates taken from their haversacks, the earth was dug up and the rails covered until a fair protection for men lying on their bellies was made.”20

For a part of the battle, portions of the XVII Corps fought in two directions, when Cheatham’s (Cheatham having temporarily replaced Hood) corps attacked out of the Atlanta defenses. But Logan’s leadership was inspiring and effective, and the Army of the Tennessee not only held but also administered a brutal rebuff to Hood’s second offensive. A Confederate brigadier described the defeat of his attack thusly: “All the regiments acted well. Taking the brigade all together, I never saw a greater display of gallantry; but they failed to take the works simply because the thing attempted was impossible for a thin line of exhausted men to accomplish. It was a direct attack by exhausted men against double their number behind strong breast-works.”21 Union troops improvised breastworks throughout the battle, so much had the tactics of the war changed from 1862. By the time the fighting had ended at dusk the Confederates had suffered over 8,000 casualties, while the Army of Tennessee had suffered 3,521—a casualty exchange ratio disastrous for the Army of Tennessee, especially considering the fact that it was outnumbered to begin with. So heavy were the Confederate casualties that Sherman doubted Hood would be able to launch another attack. He was mistaken.

Having wrecked the rail lines between Atlanta and Richmond, Sherman determined to switch his avenue of approach and swing back to the west. Howard, who had replaced the dead McPherson in command of the Army of the Tennessee, led the Union advance. Sherman had decided that Logan did not possess sufficient experience (he was a volunteer officer, as opposed to a West Pointer) to lead the Army of the Tennessee in spite of his brilliant performance in battle as McPherson’s replacement. It also appears that Thomas expressed doubts as to whether he could work with the Illinois politician.

Logan would keep his mouth shut and do his duty for the remainder of the war, but after the war he made his feelings known about the “West Point protective association.” Grant, however, had none of Sherman’s prejudice against volunteer soldiers and, as we shall see, would select Logan for higher command at the end of the year. While Logan was willing to stick it out despite being passed over, Hooker was not. “Fighting Joe” requested to be relieved from command, his pique justified by the fact that Howard’s incompetence had been responsible for Hooker’s disastrous defeat at Chancellorsville. Meanwhile, McCallum’s construction crews had bridged the Chattahoochee, a considerable undertaking which had required construction of a bridge 740 feet long and 90 feet above the river. Sherman’s forward supply base had reached his immediate rear.

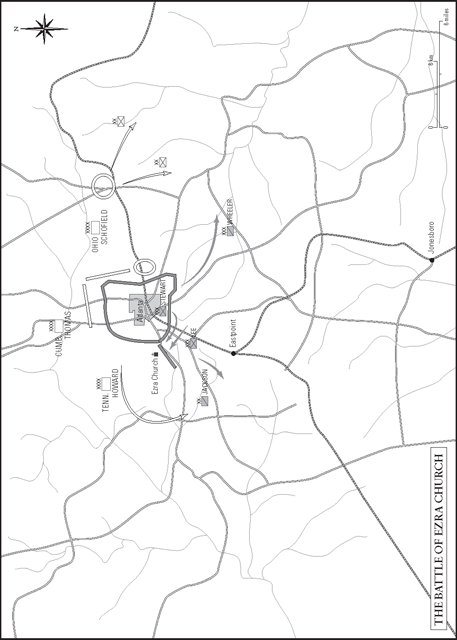

Sherman had not expected another Confederate attack; Howard knew Hood better and so had his troops ready. Hood’s third strike came on 28 July near Ezra Church. The Confederate commander planned his attack on the assumption the Confederates could seize the crossroads at Ezra Church before Sherman’s soldiers arrived, which would force the Union soldiers to deploy. Steven D. Lee had assumed command of Hood’s old corps from Cheatham, and despite his newness to the position received responsibility for the fight at Ezra Church. Meanwhile, Stewart’s corps was to swing behind Lee and move rapidly to the west so that it could swing back and catch Howard in the flank.

Howard’s men, marching rapidly south from their swing around Atlanta, reached the Ezra Church crossroads first. That completely upset Hood’s conception as to what was supposed to happen, and he had made no contingency plans. Lee simply threw his troops into straight-ahead attacks. Logan’s men reacted in the following fashion: “During temporary lulls in the fighting, which did not at any time exceed from three to five minutes, the men would bring together logs and sticks to shield themselves from the bullets of the enemy in the next assault.”22 A portion of Stewart’s corps then came up to add to the slaughter. Like the chateau generals of World War I, Hood remained in Atlanta out of touch with the battlefield. The attacks at Ezra Church cost the Confederates 3,000 casualties, while Howard lost slightly over 600.

The losses between the beginning of the campaign in May and the end of July underline how disastrous Hood’s lunges out of Atlanta had been. Over that period, Confederate casualties had reached nearly 30,000, while Sherman’s losses were approximately 26,000. Hood’s attacks had added 16,000 to the Confederate casualty bill. Given Northern superiority in numbers not only on the Atlanta front but also overall, these losses represented an exchange ratio the Confederacy could not bear. As one of Hood’s soldiers replied to the question shouted across the lines by a bluecoat as to how many men were left in the Army of Tennessee, “oh, about enough for another killing.”23

Even Hood realized that his army could not stand another killing battle. Nevertheless, his explanation for his defeats had nothing to do with his responsibility for having launched the Army of Tennessee against an immensely superior opponent, but rather focused on the supposed incompetence of his corps commanders and the lack of aggressive fighting ability among the troops, whose spirit, he argued, Johnston’s reliance on the defensive had ruined. Even Davis became alarmed at the losses in the three attacks and had ordered Hood to desist. Thus, at the beginning of August the contest between the two great armies settled into a siege. Following Grant’s example the year before at Vicksburg, Sherman began a major bombardment of Atlanta in the hope he could pry Hood loose from the city, while looking for a means to cut the lines of communications that supported the Confederates.

On 27 July, Sherman launched his cavalry around the flanks of Atlanta to apply additional pressure on the Confederates. Two columns of Union cavalry, the first of 3,500 troopers under McCook, the second under Stoneman with 6,500 troopers, were to cut the Macon & Western Railroad at Jonesboro so that the Confederates would have to abandon Atlanta. Sherman, who did not hold his cavalry commanders in high regard, had his prejudices confirmed. The raids were an utter failure. Stoneman, paying no attention to his mission, rode off with 2,500 cavalrymen to free the Union prisoners being held in appalling conditions at Andersonville and got himself and two of his three brigades captured or killed for their troubles. McCook’s cavalry force wrecked approximately a mile of track, which stopped rail traffic for two days, before fleeing back to the shelter of Sherman’s infantry. Sherman’s understated report was that “on the whole the cavalry raid is not deemed a success.”24

Yet there was an unintended effect from the cavalry’s defeat. Given the lackluster performance of Union cavalry, Hood decided he could dispense with much of his cavalry. He believed that if Wheeler cut loose and rode north with the purpose of disrupting Sherman’s rail lines of communications, Union armies would abandon their efforts to capture Atlanta and retreat back to Chattanooga. Wheeler’s raids, however, proved no more successful than the Union raids. Here and there they cut the railroads, pulled down telegraph lines, and captured supplies. But in every case McCallum’s crews repaired the damage in short order; there was no stoppage in the flow of supplies. Moreover, as with Stoneman’s efforts in the East in 1863 and in the West in 1864, Wheeler failed to concentrate on attacking the enemy’s lines of communications, but instead went on a wild ride through the countryside that eventually resulted in the destruction of most of his cavalry by the time he returned to Confederate lines in Alabama. The mistake in sending Wheeler’s cavalry off to raid Union communications in Tennessee lay in the fact that it robbed Hood of his reconnaissance force.

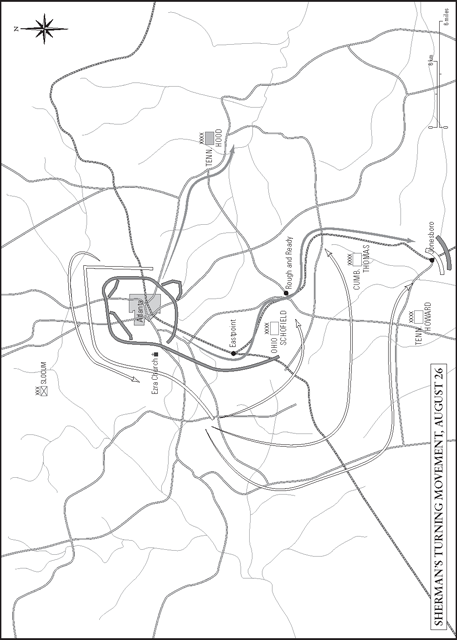

In mid-August, Sherman sent another cavalry raid against Hood’s rail lines, again with a notable lack of success. Thus, he decided he was going to have to break the Macon & Western himself. On 26 August he pulled his corps away from Atlanta except for Slocum, who now ironically commanded Hooker’s old XX Corps. Sherman’s intention was to swing his entire army around the Confederate defenses. Schofield would command the left wing, which after marching south would swing in toward the railroad station of Rough and Ready. Thomas would hold the center, and Howard’s Army of the Tennessee would aim at Jonesboro to destroy a sufficient portion of the Macon railroad to force Hood to abandon Atlanta. There were, of course, risks in such a move, because Hood might strike north at Sherman’s lines of supply. But Sherman calculated that Hood had used up the Army of Tennessee. This time he was right.

Considerable confusion marked the Confederate response to Sherman’s flanking move. With minimum cavalry available, Hood had no idea of what was transpiring other than the fact that much of the Union host had pulled back from their positions surrounding Atlanta. Was Sherman retreating because Wheeler had cut their lines of supply? Was Sherman moving around the Confederate lines? If so, how far? Where was he planning to strike? Not only was Hood blind, but the advantage in numbers that Sherman possessed was working to an even greater extent, given Hood’s profligacy with the lives of his men. By the time the Confederates reacted, it was too late. Howard’s men were astride the Macon railroad and wrecking it thoroughly, while comfortably entrenching themselves. Confederate counterattacks on the last day of August were halfhearted, but costly, totaling 1,700 to barely a quarter of that number for the defenders. Further fighting occurred on the next day, when Sherman came close to destroying Hardee’s corps, both sides suffering approximately 1,000 casualties.

On 1 September Hood abandoned Atlanta. With Sherman firmly astride the railroads supplying the Army of Tennessee and the town, Hood had no hope of holding the city. The defeat represented a political disaster for the Confederacy. Sherman’s announcement that “Atlanta is ours and fairly won” echoed throughout the North and made Lincoln’s reelection a near certainty. Ordered in haste and with little preparation, the Confederate retreat from Atlanta resembled a rout. The city’s considerable manufacturing establishments producing war material went up in smoke, along with masses of food and military equipment. With Atlanta’s capture, the Confederacy lost its second most important industrial center. The destruction of eighty-one carloads of ammunition added to the noise and light show. About the only advantage the Confederate cause gained was the fact that the Army of Tennessee regained its freedom of movement.

With the fall of Atlanta, Sherman pulled back to the city to give his armies a rest. In retrospect, his decision to reform his armies in Atlanta was a mistake. After all, the campaign’s strategic aim was not just to capture Atlanta but to destroy the Army of Tennessee, as well as to inflict as much economic damage on the Deep South as possible. By not moving rapidly to attack Hood’s demoralized army as it abandoned Atlanta, Sherman lost the opportunity to finish off his opponent. While Union armies reformed in Atlanta, Hood had equal time to reorganize the Army of Tennessee. Without baggage and with much of its artillery lost, Hood’s army represented a force capable of more rapid movement than its Union opponents. Thus, it would fight only the battles that Hood wanted to fight.

In Atlanta, Sherman took one of his more controversial steps by ordering the city’s civilians to leave. He decided to expel the city’s population partly on the basis that his lengthy logistical lines could only support his armies. But there was another reason. As he explained after the war in his memoirs: “I knew that the people of the South would read in this measure two important conclusions: one, that we were in earnest; and the other, if they were sincere in their common and popular clamor ‘to die in the last ditch,’ that the opportunity would soon come.” Or, as Sherman put it in a wartime letter to Halleck, “if people raise a howl against my barbarity and cruelty I will answer that war is war, and not popularity seeking.”25

The strategic question facing Sherman was, what next? Considerable reshuffling of senior officers and units took place. Thomas returned to Nashville with two divisions to keep a watchful eye on Forrest. Logan and Blair returned to their states to help in Lincoln’s reelection efforts. Sherman, who had none of Grant’s political understanding, found electioneering by those officers thoroughly distasteful. For Sherman, there were a number of possibilities such as a drive into Alabama toward Mobile or against Augusta. But Hood’s army remained Sherman’s main problem. Having finally recognized that he could not defeat Sherman’s armies by direct attack, Hood decided to attack the Union supply lines by moving around Atlanta to the west and then advancing northward.

Before he could move, however, Davis arrived to confer with his senior commanders. As usual the high command of the Army of Tennessee was in turmoil. Hardee in particular was unhappy and made it clear to the Confederate president that either Hood went or he would go. In conference with Davis, the other two corps commanders were no happier with Hood’s brand of leadership, while the troops greeted the president with cries demanding Johnston’s return. Caught in the web of his prejudices and a personality that refused to admit mistakes, Davis was not about to reappoint Johnston. Instead he cobbled together a command arrangement which shipped Hardee to the Carolinas, while Beauregard received general supervisory command of the Western theater, but no direct command. Finally, the Confederate president gave his blessing to Hood’s aggressive plans to take his army back into Tennessee. Both Davis and Hood believed such an invasion would draw Sherman away from Georgia. If Hood were not able to fight a battle to his advantage in Tennessee, then he was to fall back into northern Alabama where he could fight a decisive battle. If Sherman fell back into Tennessee, Hood would pursue him and defeat him there. Such were the plans of desperate Confederate leaders, who much like those in the Führerbunker in 1945 failed to recognize that the enemy has a vote as well.

Davis also revealed his increasingly fantastic attitudes toward the course of the war when he gave an address in Macon, Georgia, on September 22: “Our cause is not lost. Sherman cannot keep up his long line of communication, and retreat, sooner or later, he must; and when that day comes the fate that befell the army of the French Empire in its retreat from Moscow will be repeated.”26 Davis’s strategy by this point had become one of fantasy and delusion, which he continued to peddle to a Confederate public, increasingly despairing about the war’s course. When informed of Davis’s remarks, Grant acidly noted: “Mr. Davis has not made it quite plain who is to furnish the snow for this Moscow retreat.”27 In describing Davis’s musings, Sherman commented that the Confederate president seemed “to have lost all sense and reason.”28 In fact, Davis was sowing a whirlwind with his challenge to Sherman, whose response the Confederates of Georgia would soon regret deeply.

While Davis was speaking, Hood struck at Sherman’s lines of communications. Having gobbled up the garrisons at Big Shanty and Acworth, Hood went after the major Union supply dumps at Allatoona. Sherman watched the battle that ensued from Kennesaw Mountain, as his signalers messaged the Union garrison that help was coming. The commander of the Union force replied to Confederate demands for his surrender with the terse note that, “Your communication demanding the surrender of my command I acknowledge receipt of, and respectfully reply that we are prepared for the ‘needless effusion of blood’ whenever it is agreeable to you.”29 The fight cost Union defenders 707 casualties; the Confederates 799, but the supply depot remained in Union hands.

The upshot of the attack was a series of skirmishes that forced Hood to retreat into northern Alabama; there he remained a latent threat, but his attacks were more than a mere nuisance, because they left the initiative in Confederate hands. As Sherman fended Hood off from his railroad lines of communications, he contemplated a major change in his strategic approach. As long as he remained tied to Atlanta, his lines of communications would remain vulnerable to Confederate raids. Moreover, given his position in northern Alabama, Hood could attack in a number of directions, any one of which might cause difficulties. The combination of the Army of Tennessee with Wheeler’s and particularly Forrest’s ability to raid led Sherman to warn Grant and Stanton that the Confederates possessed the ability to inflict up to 1,000 casualties on static Union garrisons each month.

What Sherman proposed as a solution was that his armies abandon Atlanta with a portion falling back into Tennessee. At the same time Sherman would march with 65,000 handpicked troops through central Georgia to bring the war home to the Deep South. As he put it: “On the supposition always that Thomas can hold the line of the Tennessee, and very shortly be able to assume the offensive against Beauregard, I propose to act in such a manner against the material resources of the South as utterly to Negative Davis’ boasted threat and promises of protection. If we can march a well appointed Army right through his territory, it is a demonstration to the World, foreign and domestic, that we have a power which Davis cannot resist. This may not be War, but rather Statesmanship.”30 Initially Grant was skeptical, but Sherman soon won him over. After all, had not his Army of the Tennessee lived off much poorer land in Mississippi during the Vicksburg campaign? It took Grant’s log rolling to persuade Lincoln and Stanton that Sherman’s approach was a war-winning strategy. In the end they too agreed.

For Sherman the immediate task was to clean up the loose ends preparatory to this march through Georgia. Thomas assumed command in Tennessee with Schofield under him. Not surprisingly, the two subordinates Sherman selected to remain behind to defend Tennessee were the two generals most capable of acting on their own. To command the army’s wings in the march through Georgia, Sherman selected Slocum and Howard. He would remain with Howard throughout much of the campaign. Given the fact he did not expect serious military opposition on the march to the sea, the distribution of senior officers made sense. As he prepared, Sherman sent the sick, as well as those lacking the fortitude for such a march, back to Nashville. These were to provide Thomas and Schofield with the strength to counter any of Hood’s aggressive moves. Thus, through October into November, Thomas received a steady flow of reinforcements. David Stanley’s corps moved out of Atlanta to Nashville, while A. J. Smith’s divisions returned from Missouri to add to the forces gathering under Thomas in Tennessee.

As he had with the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry when he had appointed Sheridan, Grant intervened to fix the cavalry in the West. With few exceptions, Grierson being one, its record had been little better than that of its Eastern brethren, especially against Forrest. As one infantryman acidly commented: “Confound the cavalry. They’re good for nothing but to run down horses and steal chickens.”31 So Grant sent James Wilson to shape up the cavalry supporting Thomas. Wilson obviously did not have time to affect matters before Hood crossed into Tennessee, but he was to render a crucial service during the campaign. As for Hood, Sherman caustically commented: “Damn him, if he will go to the Ohio River I’ll give him rations. … Let him go north, my business is down South.”32 Thus, Sherman changed the basis of Union strategy in the West. It now focused on carrying the war to the Confederacy’s civilians, in this case white Georgians, but others would soon feel the power the North was willing to bring to bear to break Confederate will.

Hood’s army, unless it was willing to defend Georgia, which its current placement in northern Alabama indicated it was not, was an irrelevancy. Given Union strength in Tennessee, it had little prospect of achieving much, and if it were to seek out battle against Thomas and Schofield, it had every prospect of being destroyed. Yet, Hood was toying not only with invading Tennessee but also with coming to Lee’s aid, if Sherman refused to fight. Nevertheless, Hood turned down the possibility of attacking Sherman in mid-October on the advice of his corps commanders, who argued that the shaky morale of their troops and the numbers available made the prospects of success minimal.

Hood, Davis, and Beauregard saw nothing of the possibilities open to Sherman. As is true of much of military history, there was a distinct lack of imagination among Confederate leaders as to the path on which their opponent might embark. Instead of recognizing Sherman’s options, they expected Sherman to follow Hood into the rugged terrain of northern Alabama and southeastern Tennessee, where separated from his supply bases, his forces would shrink. At that point, supposedly Hood and the Army of Tennessee could destroy Sherman’s armies. Shortly before assuming his new position in the West, Beauregard met with Hood. Hood laid out his plans for an invasion of Tennessee, which sounded much like the course of action Beauregard had been urging on his government over the past two years with one important difference: Beauregard had always urged that major reinforcements be sent West to reinforce the Army of Tennessee, but now the cupboard was bare; Hood was proposing the Tennessee offensive with an army which had suffered heavy losses as a result of his generalship and the morale of which had not yet recovered, if ever it would. Moreover, the maneuverability that had allowed Hood to escape Sherman’s grasp was a result of the fact that the Army of Tennessee’s logistical system was almost nonexistent.

What is astonishing about Hood’s movements at the end of October and into early November is that the crippled general had no clear idea of exactly what he intended to accomplish. He was clearly ad-libbing, making up strategy as he went along. Initially, it appears he hoped to break the railroad lines between Nashville and Chattanooga. Driving Hood was the dream that not only could he defeat Thomas, capture Nashville, and recruit 20,000 volunteers in Tennessee, but also drive all the way to the banks of the Ohio, a goal that Confederate armies had failed to achieve during the heyday of their success in summer 1862. Thus, the Army of Tennessee approached Guntersville, Alabama, with the intention of crossing the Tennessee River at that point.

But a strong Union garrison held the crossing, and Hood decided that his army would suffer too heavy casualties, were it to attempt to force a crossing. Upon reaching Decatur, Alabama, fifty miles downstream, Hood reached the same conclusion, given the strength of Union forces at the crossing. So it was another long march down the swollen Tennessee to Tuscumbia in the northwestern corner of Alabama. Over a ten-day period, Hood wandered around northern Alabama looking for a crossing point. At Tuscumbia he wasted more time waiting for Forrest to join up, since Forrest had engaged his troopers in a successful raid in wrecking Union supply depots along the lower Tennessee. The property damage was considerable, but whether the Confederacy gained in strategic terms is doubtful. The delay, however, did allow Union commanders on the other side of the river to prepare themselves to meet the Army of Tennessee.