The Confederacy Recovers, 1862

Alexander, if there is one man in either army, Federal or Confederate, who is, head & shoulders, far above every other one in either army in audacity that man is Gen. Lee, and you will soon live to see it. Lee is audacity personified. His name is audacity, and you need not be afraid of not seeing all of it that you will want to see.

—Edward Porter Alexander, Fighting for the Confederacy

[The blast] seemed to shake the very earth. Then the dull thud of the balls as [they] tore … through the bodies of the men—then the hiss of the grape—and mangled screams of agony and rage. I looked around me. The ground was filled with the mangled dead and dying.

—Quoted in John Hennessy, Return to Bull Run

In late December 1861, Senator Benjamin Wade, a member of the increasingly Radical Republicans, commented to Lincoln: “Mr. President, you are murdering your country by inches in consequence of the inactivity of the military.”1 Undoubtedly, Lincoln agreed, but, of course, he had to dissemble in public. For eight months, the North had been building great armies. Yet, its generals seemed incapable or unwilling to attack the Confederacy. Moreover, the soldiers of the Republic were consuming vast sums of money as well as the nation’s resources. And for what? By the end of 1861, the North was becoming less enthralled with the splendid parades and military displays McClellan was mounting week in and week out. All the while, a Confederate army under Joe Johnston remained at Manassas. Parades were fine, but the public and many of the solders wondered why McClellan seemed unwilling to mount any sort of military operations against the Republic’s enemies, who remained untouched within sight of the nation’s capital. McClellan fell ill with typhoid fever in December, further compounding problems, since his illness stalled planning and confined the general to his bedside during a crucial political moment when congressional Republicans began to question his military leadership.

Well might Lincoln bemoan on 10 January 1862 to Montgomery Meigs, the army’s quartermaster general, that “the bottom is out of the tub.”2 Lincoln’s frustration with the military at the turn of the year showed in a number of ways. Displaying a feel for strategy, the president suggested that if all the Union armies were to move at the same time, they would place such pressure on the Confederacy with its fewer resources that somewhere the enemy would break. On 6 January, Halleck had pedantically lectured the president that he could not act in the West because “to operate on exterior lines against an enemy occupying a central position will fail, as it has always failed, in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred. It is condemned by every military authority I have ever read.”3 Lincoln’s reply—quoted in the last chapter in full—was clear and to the point: Since the Union has greater numbers and the Confederates “greater facility of concentrating,” the Union needed to remove that advantage by “menacing him with superior forces at different points, at the same time” thus weakening the Confederates at some critical point.4 Not for the last time, Halleck displayed his inability to match military theory with operational reality.

Unlike Halleck, McClellan valued coordinated operations across the Confederacy’s frontiers, but his preoccupation with the Army of the Potomac’s supposed weakness vis-à-vis Johnston demanded that his army monopolize the Union’s resources, and all other operations support his own primary line of effort. Furthermore, his caution and prejudice against action weakened his earlier attempts to cajole Buell and Halleck into action in the West—although he did attempt to no avail to get both generals to move. Most importantly, McClellan never understood that the Confederacy had its own vexatious resource problems, exacerbated in the West by its choice of a cordon defense and compounded by the overconfidence produced by the early victory at First Manassas. Indeed, the Confederacy would not belatedly institute conscription until spring 1862, after the catastrophic defeats in Tennessee and the Western theater.

In the end, Lincoln was right and Halleck wrong. In fact, operations in the West in 1862 would crack the Confederacy’s cordon defense and create the basis on which the North’s eventual victory rested. Nevertheless, military operations west of the Alleghenies were far from Washington and Virginia. Even to the amateurs of 1861, it was clear that no decisive victory was possible in the west where Union armies confronted the logistical problems raised by that theater’s distances and where there was no single city matching Richmond in its political and economic importance. Thus, military operations there could not achieve the decisive victory needed to bring an increasingly costly war to the quick and successful conclusion, for which Lincoln, the Congress, and the people of the North still fervently hoped. Such a victory could come only in the east.

The problem in Virginia in fall 1861 was that McClellan was already giving wild overestimates as to the size of Johnston’s army. Equally distressing to the administration was that McClellan seemed to have no plans for future military operations. As we have seen, McClellan had in fact made plans—and ones with merit no less—but his contempt for Lincoln and obsession with secrecy caused him to withhold his plans until his political position became virtually untenable. In early January Lincoln even had to admit to Congress’s Committee on the Conduct of the War that he had no idea of McClellan’s plans. To some more cynical or impatient observers, it appeared McClellan’s objective was to avoid battle with the Confederates. For most in Washington, the obvious solution was for the army to march out and destroy the Confederates who stood at Manassas on the capital’s doorstep. But McClellan continued to emphasize the superior numbers Johnston supposedly possessed. Moreover, the fact that the Union commander was seriously ill further complicated his relations with Lincoln and the administration.

At least the fact that McClellan was bedridden allowed the president to seek advice from several other generals. On 10 January, after a long conversation with Meigs, Lincoln invited two of the Army of the Potomac’s more senior officers to a discussion. So McDowell and Franklin accompanied Seward to a meeting with the president to examine the army’s options. Thus, Lincoln had the opportunity to discuss the situation with individuals who had some grasp of military matters as well as an opportunity to vent to his frustrations. He commented to the group that “he would like to borrow [the Army of the Potomac], provided he could see how it could be made to do something.”5 Alarmed by the possibility the president was seizing the reins of military strategy from his hands, McClellan roused himself from his sickbed to attend the next meeting. Nevertheless, outside of several arrogant interventions, he added little to the discussions. Bon mots that he threw out—such as “the case was so clear that a blind man could see it”—provided no insights into his thinking.6 Asked about his plans by Chase, he refused to answer, only stating that he awaited Buell to act first in Kentucky. He even whispered to Meigs that he dared not tell the president anything, because it would immediately appear in the papers.

Lincoln adjourned the meeting without showing obvious anger, but McClellan had once again harmed his own political situation through willful obstinacy. Not surprisingly, his position in Washington continued to deteriorate. Thoroughly frustrated with his senior generals, Lincoln took matters into his own hands. At the end of January, he issued General Order No. 1, in which he ordered that by 22 February 1862, the armies of the United States were to begin a forward movement. Although the order was unrealistic, especially considering the time of year, it did reflect Lincoln’s strategic conception. On 31 January, Lincoln, further annoyed by McClellan’s obfuscations, specifically ordered the Army of the Potomac to move on Manassas and the Confederates. The threat of action galvanized McClellan, who objected violently and replied with a verbose, twenty-two-page letter to Stanton, proposing an alternative. Lincoln had finally smoked the general out. McClellan informed his commander in chief of his plan to move the army down the Potomac and land at the mouth of the Rappahannock River at Urbanna, thereby outflanking Johnston’s position at Manassas. Lincoln had little enthusiasm for the idea, because with the enemy army directly in front of Washington, it seemed McClellan could attack the Confederates any time he wished. The president also feared such a move might leave Washington undefended.

Events in early March settled the matter in McClellan’s favor. Johnston, quite rightly, believed that, in view of the numerical superiority of Union forces as well as the logistical difficulties of supplying his troops in northern Virginia, it made sense to withdraw from Manassas. The Confederate retreat revealed how wildly McClellan had overestimated the enemy. The fortifications in front of Manassas were almost entirely a sham, armed with large logs, while the size of Johnston’s abandoned encampment showed the Confederates had possessed a troop strength of no more than 50,000 soldiers. Despite this indication of Confederate weakness, McClellan would persist throughout spring and summer 1862 in overestimating his opponents by a wide margin.

Johnston’s retreat then led McClellan to propose a riskier strategy of moving most of the Army of the Potomac to the York Peninsula, which the York and James Rivers bounded and which led directly to Richmond. Lincoln was even less enthralled by the new proposal, but at least McClellan was suggesting action. The president agreed, provided sufficient troops remained to defend the nation’s capital. Therein lay the seeds of a major blowup in the future between president and general. On 9 March, the fortuitous arrival of the Union ironclad Monitor at Fort Monroe, at the tip of the York Peninsula across from Norfolk, checkmated the Confederate ironclad Merrimack and opened the way for a land assault on Richmond.

The Peninsula Campaign

Before the move against Richmond began, Lincoln himself stepped in to force a corps organization on McClellan. The president named the Army of the Potomac’s initial corps commanders for Corps I-IV on the basis of seniority. McClellan had preferred to wait until combat revealed which division commanders had the highest potential, but Lincoln had good reason to force the issue, since managing so many divisions without an intermediate echelon of command defied a well-known lesson of the wars of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Furthermore, it was apparent the absence of corps commanders in the army was exacerbating McClellan’s tendency toward micromanagement.

However, McClellan did have more control over the composition of what eventually became the Army of the Potomac’s V and VI Corps, because unlike the first four corps, he named both of their corps commanders. Looking at the composition of these corps, one sees again a preference for engineers—William B. Franklin had been a topographical engineer in the Old Army, along with one of his two division commanders, William F. Smith. In the V Corps, one of the two division commanders, George W. Morell, had graduated from West Point, like McClellan, into the Corps of Engineers. The two new corps also reflected McClellan’s preference for the regulars, since the V Corps included a new division of regulars, headed by George Sykes, who had started the war commanding a regular army battalion in the First Battle of Bull Run.

The combat performance of the generals McClellan handpicked for the V and VI Corps also reflected the weaknesses of the command culture he was creating, although there were some redeeming elements. Franklin would have a poor record as a corps commander, and his indecisiveness, combined with Burnside’s failings, would contribute to the Union catastrophe at Fredericksburg. Fitz-John Porter, whom McClellan prized above all his other subordinates, would vindicate his superior’s confidence by fighting off successive assaults by Lee during the Seven Days battles, and unlike his chief, he proved willing to stand and fight after the Confederate repulse at Malvern Hill. However, like McClellan, Porter wore his conservative Democratic politics on his sleeve, and this clearly contributed to his unwillingness to cooperate wholeheartedly with Pope at the Battle of Second Bull Run. When combined with his extraordinary political indiscretions, his military errors during the Second Bull Run led to his eventual expulsion from the service, to the detriment of the Army of the Potomac’s weak bench of capable corps commanders.

Of the division commanders in V Corps, Sykes would eventually prove a competent corps commander, although not an exceptional one. Morell, the former engineer, would top out at division command. In the VI Corps, Henry W. Slocum, as we shall see, would rise to corps command, but prove unworthy of that responsibility. Smith would prove a fine senior engineering officer who helped Grant open the cracker line to relieve Chattanooga in fall 1863, but a mediocre corps commander in summer 1864. In this respect, he was similar to Gouverneur Warren, who served as a brigade commander in V Corps, and who later did fine service as an engineering officer at Gettysburg, but who would falter as VI Corps commander in the 1864 battles.

From Lincoln’s perspective, the decision to allow McClellan to embark on the Peninsula campaign rested on his understanding that the general would leave sufficient forces to guarantee the capital’s safety. McClellan, however, believed that it was up to him to decide on the size of that force, but from the president’s point of view the administration was not about to trust an officer who seemed to be playing games with numbers. On that difference of opinion rested the quarrel that soon erupted between Washington and the Army of the Potomac’s commander.

The move to the York Peninsula underlined the size of the mobilization of the North’s resources over the war’s first year. The Union’s extraordinarily capable quartermaster general, Montgomery Meigs, had assembled a fleet sufficient to transport McClellan’s 100,000 men; 300 artillery pieces, including siege artillery; the assorted mules and horses the army required; and the vast impedimenta of ammunition, rations, and other supplies necessary for the conduct of military operations on the Peninsula. But at the last moment, Lincoln and Stanton discovered that McClellan had assigned far fewer troops to Washington’s defense than promised. Alarmed, they ordered McDowell’s corps of some 35,000 troops to remain in northern Virginia, thus robbing McClellan of a substantial body of troops. In fact, McClellan had more than sufficient troops to launch his campaign, but that was not how he saw matters. In retrospect, no matter how many soldiers McClellan received, nothing would have changed his unwillingness to engage the enemy. Nevertheless, the presence of McDowell’s Corps with the Army of the Potomac during the Seven Days battles might have shattered Lee’s army, in spite of McClellan’s distaste for the tactical offensive.

As the first contingents of the Army of the Potomac arrived at Fort Monroe, the Confederate leaders puzzled over their enemy’s intentions: were the Federals moving against North Carolina, or Norfolk, or did this arrival herald a move up the York Peninsula against the Confederate capital? But as more Union forces arrived, uncertainty about McClellan’s intentions dissipated. A major offensive against Richmond was clearly in the offing. And Richmond was vulnerable. Major General John Magruder, an officer renowned in the Old Army for his thespian talents, guarded the city’s approach with slightly fewer than 15,000 troops, a number hardly sufficient to put up token resistance, had McClellan moved quickly. But Lee, acting as Davis’s military advisor, recognized that Union forces were coming in strength and detached three divisions from Johnston’s army now on the Rappahannock and sent them to reinforce Magruder.

On the other side, McClellan had hardly arrived on the Peninsula when he learned that McDowell’s corps of 35,000 troops would not reinforce him and that the administration had removed Banks’s army in the Shenandoah from his command. Lincoln attempted to invigorate his commander in the field with words which even in the twenty-first century ring with political and strategic wisdom: “Once more let me tell you, it is indispensable to you that you strike a blow. I am powerless to help this. You will do me the justice to remember I always insisted, that going down the Bay in search of a field, instead of fighting at or near Manassas, was only shifting, and not surmounting a difficulty—that we would find the same enemy, and the same, or equal, intrenchments, at either place. The country will not fail to note—is now noting—that the present hesitation to move upon an intrenched enemy, is but the story of Manassas repeated. … I have never written you, or spoken to you, in greater kindness of feeling than now, nor with a fuller purpose to sustain you, so far as in my most anxious judgment, I consistently can. But you must act.”7

But McClellan failed to act with dispatch. Not far from the Yorktown battlefield of the Revolutionary War, Magruder constructed a line of fortifications across to the Warwick River, which he had his engineers dam. The fortifications may have looked impressive to McClellan, but as Johnston commented when he first saw them, “no one but McClellan could have hesitated to attack.”8 Adding to the show, Magruder marched his soldiers into the fortifications during the day and then snuck them out during the night, to repeat the exercise day after day. Magruder’s antics thoroughly entranced McClellan, who spent a month preparing to conduct a needless siege, as horses and mules dragged the siege artillery up the primitive, muddy roads, made worse by heavy spring rains. It took nearly a month to complete his preparations.

Finally, on 3 May, with McClellan ready to bombard Magruder’s fortifications, Johnston ordered a retreat up the Peninsula to the defenses on Richmond’s eastern side. Lee had organized and sited those defenses during April. Davis was furious at the withdrawal, particularly because Johnston had informed the Confederate president only at the last moment. Davis, with bad news flooding into Richmond from other fronts, desperately needed aggressive action to defend the capital. Whatever difficulties the Confederates faced, McClellan had done nothing to prepare for the possibility the Confederates might withdraw from their fortifications. Ever cautious, he trailed the retreating Confederates at snail’s pace. In a short skirmish near Williamsburg, advancing Union troops ran into James Longstreet, already achieving a name for himself as a combat commander. Both sides suffered several thousand casualties, but more importantly the fight slowed McClellan’s advance even further. An incident involving McClellan and his staff best sums up the Union approach to the campaign, as it crawled slowly toward Richmond. Coming across a stream, McClellan and his staff halted to debate its depth. After ten minutes or so, an impatient staff officer, a certain Captain George Armstrong Custer, rode into the middle of the stream and turned to his commander with the comment: “That’s how deep it is, General.”9

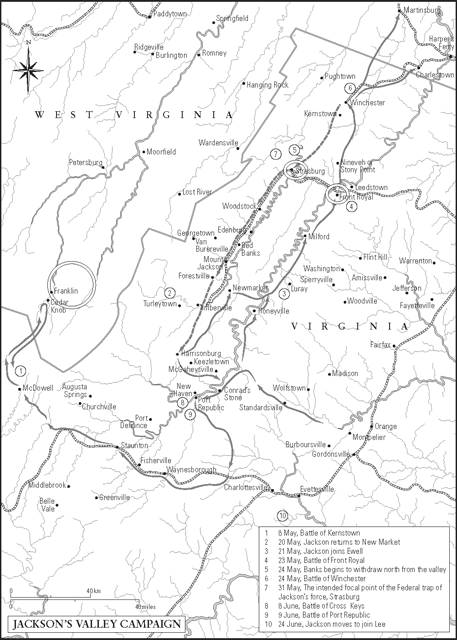

By the end of May, two months after landing on the Peninsula, the Army of the Potomac was only six miles from Richmond. Moreover, Lincoln had released McDowell’s corps to march south, cross the Rappahannock, and then join McClellan’s right wing, thus providing the general with the troops he claimed he needed. But fate in the guise of Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson intervened to launch a series of brilliant strokes in the Shenandoah Valley. Jackson with his small army had suffered a nasty rebuff in March 1862. Moreover, his harsh, unbending personality hardly endeared him to the troops. Grim, dour, humorless, Jackson was all of that, but a military genius as well. Yet, Lee had recognized the qualities of command behind one of the strangest personalities ever to command a major force in the war. Jackson also had a thoroughly unromantic understanding of war. When one of his colonels praised the valor some Union cavalry had displayed, Jackson simply commented: “Shoot them all: I do not wish them to be brave.”10 Now in May Jackson struck again, this time with devastating success.

Surreptitiously Lee had fed Jackson reinforcements. On 16 May, as the Army of the Potomac approached Richmond with the possibility that Washington would release McDowell’s corps to join McClellan by marching across central Virginia, Lee urged Jackson to launch a full-scale attack on the Federals in the Valley, as well as to strike all the way to the Potomac, so that the Federals would conclude the Confederates were about to strike into Maryland, and perhaps even against Washington. Thoroughly familiar with the Shenandoah due to his extensive journeys throughout the area before the war and possessing excellent maps, Jackson utilized his knowledge of the Valley as well as his ability to drive troops to the brink of exhaustion and beyond. The Valley’s complex geography aided his campaign. To the west lay the formidable Allegheny Mountains. To the east bounding the Valley was the Blue Ridge, while a thin ridge, Massanutten Mountain, divided the east fork of the Shenandoah River from the west fork. Only a narrow gap with a narrow road ran through Massanutten Mountain.

At the beginning of his campaign, Jackson had already struck the lead elements of Frémont’s forces, which were advancing through the Alleghenies toward Staunton and the upper (southern portion) Valley on 8 May. The outnumbered Union troops put up solid resistance and fell back into the mountains after inflicting as many casualties on the Confederates as they suffered. But Jackson had achieved his goal of ejecting Frémont from the complex equation of Union forces in the Valley. He then turned north, and after feinting as if to join Johnston near Richmond, he marched north to burst on Nathaniel Banks’s corps guarding the northern part of the Shenandoah. Banks had already divided his forces to handle guerrillas, since he did not believe Jackson represented much of a threat, while Union intelligence had reported Jackson on his way to reinforce Johnston.

Like the Assyrian sweeping down “like the wolf on the fold,” Jackson destroyed Union positions in the Valley in a matter of weeks.11 By forced marches, he drove his troops to Front Royal, where on 23 May he destroyed the outnumbered garrison. Out of 1,000 Union troops, 904 were either dead, wounded, or captured. Jackson suffered fewer than fifty casualties. Banks possessed approximately 6,000 troops just down the road from Front Royal at Strasburg, while his main supply dump lay up the Valley Pike at Winchester with 1,500 more soldiers. Jackson, however, had over 17,000 soldiers, far better trained and led than Banks’s motley crew. Banks almost made the mistake of holding Strasburg, which would have put his entire force in the bag, but at the last moment his subordinates persuaded him to retire.

It did not matter, because Jackson caught up with the retreating Banks and his troops at Winchester and in a short decisive battle on 24 May smashed the outnumbered and badly deployed Union troops. Jackson captured a mountain of supplies, which led his troops to refer thereafter to the defeated Union general as “Commissary Banks,” and pursued the Federals to the Potomac. But to Jackson’s disgust most of the beaten army escaped. Banks attempted to cover up the extent of his defeat by reporting to Washington that “it is seldom that a river-crossing of such magnitude is achieved with greater success.”12 Jackson’s campaign in the Valley has drawn the praises of military historians since the war’s end. It was indeed a piece of tactical virtuosity, but its real impact was political and operational. On the political side, it restored Confederate morale after the string of stinging defeats in the west over the previous five months. Equally important it had a significant impact on decision making in Washington. Lincoln and Stanton halted McDowell’s march to reinforce McClellan just over the Rappahannock and concentrated Union forces in the Shenandoah to assuage the humiliation of the last several weeks by destroying Jackson before he could do more damage.

At the end of May McClellan had reached Richmond’s outskirts. He deployed two of his corps, the II Corps under Samuel Heintzelman, and the IV Corps under Erasmus Keyes, neither particularly competent officers, south of the Chickahominy Creek, a muddy stream that ran southeastward from north and east of the Confederate capital. The two corps numbered approximately 31,500 men. McClellan kept the other three corps, led by Fitz-John Porter (V Corps), William Franklin (VI Corps), and Edwin “Bull” Sumner (II Corps), on the north side of the stream. At least to McClellan, there did not appear to be any danger in splitting the army in such a fashion, but it was in fact a piece of bad tactics. The creek was a languid, insignificant body of water, over which Union engineers had constructed a number of bridges, facilitating the transfer of troops back and forth across the Chickahominy. But on the last day of May, the skies opened up and a raging torrent swept most of the bridges away.

On that day Keyes’s corps was in the lead south of the Chickahominy and was approaching the hamlets of Fair Oaks Station and Seven Pines, only seven miles from Richmond, when Johnston struck. To do so Johnston concentrated twenty-three of the twenty-seven brigades under his command on the south side of the Chickahominy. McClellan’s decision to divide his troops gave the Confederates the opportunity to destroy one-third of the Army of the Potomac. If things had gone right, the Confederates might well have destroyed the entire left wing of McClellan’s army. But the fight was one of the most badly botched battles of the war. From its opening moments, the Southern attack got off on the wrong foot. Longstreet was the author of much of the delay by changing Johnston’s orders and placing the focus of the Confederate attack on the center. D. H. Hill, Stonewall Jackson’s brother-in-law, conducted most of the fighting on the first day. Floundering through knee-deep mud, the Confederates found themselves engaged in a furious firefight and eventually drove Keyes’s men from their positions.

But the cost was heavy. In the lead, Robert Rodes’s Confederate brigade suffered 50 percent casualties. Heintzelman had proved sluggish during the fighting, but “Bull” Sumner, charged by McClellan with providing reinforcements if necessary to any threatened sector, displayed unusual initiative for the Army of the Potomac—although he owed his position as a corps commander not to McClellan but to his prewar seniority. Not only had he prepared his troops to move, but he then led them across the flooding waters of the Chickahominy on the rickety bridges over the creek. While the generalship on both sides was less than impressive, the fighting was fierce, as the enlisted ranks on both sides savaged each other. The Confederate success was less than expected: 6,000 casualties with 5,000 on the Union side.

The most significant event of the battle was that Johnston had ridden forward to see how matters were progressing as the fighting died out. Moving too close to Union lines, the Confederate commander was severely wounded by shrapnel and a bullet. Davis had no choice but to name Lee as Johnston’s replacement. In a letter to Lincoln in late April, McClellan had assessed his new foe in the following terms: “I prefer Lee to Johnston—the former is too cautious & weak under grave responsibility. Personally brave & energetic to a fault, he yet is wanting in moral firmness when pressed by heavy responsibility & is likely to be timid & irresolute in action.”13 The president and “Young Napoleon” were about to discover how flawed McClellan’s judgment was on the capabilities of officers he should have been thoroughly familiar with from his days in the regular army.

As soon as he assumed command of Confederate forces in Virginia, Lee set the stage for the destruction of part, if not all, of McClellan’s army and the achievement of what he believed would be the decisive victory to gain Confederate independence. For most of the rest of June he annoyed his troops by having them extend and deepen Richmond’s defenses by day after day of digging. Although it seemed to the soldiers that Lee was preparing to fight a defensive battle, he had no such intention. Instead, the purpose of such defensive works was to free up troops so that he could launch killing blows at the Army of the Potomac. However, until Jackson could move out of the Valley to reinforce Lee, the Confederates would lack sufficient troops to achieve the kind of victory Lee was seeking.

In the Shenandoah, Jackson, whose advance had carried his army almost to the bank of the Potomac, had placed himself and his army in a dangerous position. Lincoln recognized the possibility of trapping the Confederates in the lower Valley near the Potomac. Using the telegraph, the president and Stanton attempted to coordinate Union armies to trap Jackson. For the Confederates, only the gap between Front Royal and Strasburg remained open. Their escape depended on whether Jackson’s soldiers could outrace Union attempts to close the gap. Jackson won the race with the “Stonewall” Brigade, Jackson’s old command, which he had left behind as a rear guard, marching through the gap before Union troops arrived.

Jackson had barely escaped this pincer movement when Frémont’s command moved south on the Valley Pike and attacked from the northwest near Port Republic. At the same time James Shields’s division attacked from the northeast on the southern side of the south fork of the Shenandoah. The fighting on 8 June saw the Confederates drive off both Union armies with relative ease, since neither Frémont nor Shields possessed the toughness to drive home their attacks. A second fight the next day saw the same result, with another tactical victory for Jackson, although Union troops drew off in relatively good order. In tactical terms, Jackson’s two victories gave the Confederates control of the upper and central portions of the Shenandoah. But the strategic aspects of his success were of greater importance. The defeats so bruised Union troops and their commanders that they no longer posed a threat to the Confederate position in the central and southern (upper) portions of the Shenandoah. With the Union threat neutralized, Jackson was now able to move from the Valley to reinforce Lee outside Richmond.

Lee had set the stage for what he hoped would be the decisive battle of the Civil War. On taking command, he had informed Davis as to plans to hold south of the Chickahominy with a small part of the army, which also consisted of his weakest troops. Meanwhile, he planned to use the bulk of his army, reinforced by Jackson, to destroy the force McClellan had deployed north of the Chickahominy. The Confederate president had doubts. He feared that with Lee concentrating on McClellan’s northern flank, McClellan would launch an overwhelming attack on the southern front that would break through and capture Richmond. Nevertheless, Lee was persuasive.

On the other side, McClellan again played into Confederate hands. Despite the dangers of splitting his army that Seven Pines/Fair Oaks should have suggested, he now concentrated four corps south of the Chickahominy, while only Porter’s corps remained north of the river in case McDowell’s corps were to be released from its position along the Rappahannock and advance south to link up with McClellan. However, Union supply lines still ran from White House near the York River. Thus, an attack on the Union right (northern) flank, might separate the Army of the Potomac from its key base. McClellan did take the precaution of preparing to move his logistical base from the York River to the James, the Peninsula’s southern boundary. But for all of McClellan’s caution, Porter’s flank remained up in the air, virtually inviting a Confederate attack. J.E.B. “Jeb” Stuart confirmed these weaknesses during a reconnaissance that took his cavalry entirely around the Army of the Potomac with the loss of only one soldier.

McClellan deployed his corps as follows: Porter’s V Corps north of the Chickahominy, holding positions along Beaver Dam Creek, well in advance of the remainder of the army’s corps on the other side of the Chickahominy. Franklin’s VI Corps held positions closest to the south bank of the river, while to its south Sumner’s II Corps, Heintzelman’s III Corps, and Keyes’s IV Corps deployed in that order. In retrospect, what remains astonishing is that while McClellan believed the Confederates outnumbered him (he wired Stanton the enemy possessed 200,000 men), his dispositions suggest he lacked the imagination to consider the possibility the Confederates might attack him.

As was to occur later in the summer during the Antietam campaign, McClellan possessed an excellent piece of intelligence prior to battle. A Confederate deserter reported that Jackson with three divisions would soon arrive and that Lee was about to launch a major attack on the Union right. McClellan paid not the slightest attention. By 0800 on the morning of 26 June, Lee was ready. He had positioned A. P. Hill’s division to strike Porter directly across Beaver Dam Creek, while Longstreet and D. H. Hill were to support when needed. But the main blow was to be Jackson, whose troops had arrived from the Valley and were to attack Porter’s exposed right flank. The Confederate attack on 26 June represented a situation in which Lee had positioned the pieces of his army for a devastating blow with every chance of destroying Porter’s entire V Corps. It never happened, because Jackson never arrived. The best guess is that the dour general had so exhausted himself by a lack of sleep that he had severely diminished his capacity for clear thinking. Thoroughly annoyed by having to wait for seven hours in the boiling sun, A. P. Hill launched his men in a straight-ahead attack across Beaver Dam Creek. The attackers, 11,000 strong, had little chance against 14,000 Union troops, some of whom had entrenched. Jackson’s troops finally arrived late in the afternoon but failed to involve themselves in the fighting. The casualty figures reflected a less than auspicious start for Lee’s offensive: Confederate 1,475, Union 361.

In retrospect, Lee had lost his best chance to deal a killing blow against McClellan. The frontal attacks had set Porter up for the sort of fierce flanking attacks which Jackson had launched against his enemies in the Valley and which he was to launch at Chancellorsville ten months later. In fact, Jackson would have had an advantage that he would not possess in 1863—namely, major Confederate forces would be holding the V Corps on its front, while the flank attack could have rolled Porter’s troops back on the Chickahominy. Such an attack would have destroyed the V Corps, since it had no possibility of retreat or reinforcements to save it from destruction. But Lee was never one to focus on past failures, and so the Confederates moved on. On the other side, McClellan proved why he was a poor tactician as well as moral coward as the commander of an army (McClellan had shown plenty of physical courage as a junior officer in Mexico). First of all, he merely sent Porter congratulatory messages. With massive superiority south of the Chickahominy, he failed to attack on that sector, undoubtedly reinforced in that decision by his continued overestimations of Confederate strength. Magruder’s theatrical displays south of the Chickahominy convinced Union corps commanders that McClellan was right in his estimates. McClellan ordered Porter to fall back from his Beaver Dam defensive position, while the latter transferred the V Corps’ supply train across the creek. Most importantly, while he instructed Porter to remain on the north bank in a holding action, McClellan neglected to send Porter any reinforcements. For all his faults, Porter fought his corps well, and he retreated to an even stronger position to the rear of Botswain Swamp two miles to the east of Gaines Mill, but his right (northern) flank remained up in the air.

Having seen his plan to have Jackson crush the V Corps flank fail, Lee, ever the gambler, determined to try again on the 27th. Despite the fact that Porter was fully alert, Lee determined on a repeat of the previous day’s plan. However, Jackson, as had been the case the day before, was late. The initial Confederate attacks collapsed before devastating fire from Porter’s newly dug-in positions. Jackson finally arrived late in the afternoon to attack the Union flank, but Major General George Sykes’s regulars on the right of Porter’s line held their positions. At that point, Brigadier General John B. Hood’s brigade of Texans, supported by another brigade, charged into the middle of the Union lines and succeeded in smashing their way through. But the Confederates were facing different troops than they had faced the year before at Manassas. The Union troops on the flanks of the breakthrough did not collapse, but pulled back in a disciplined fashion. Moreover, it was already twilight, McClellan had finally sent reinforcements, and the broken troops soon reformed. In the gathering gloom, the Confederates had to call a halt to their attack. Over the night, the V Corps retreated across the Chickahominy. The fight represented a Confederate victory, but only a tactical one. Porter and his V Corps had escaped.

On the 28th Lee hesitated, because he was not sure whether McClellan, positioned with his army on the right bank of the Chickahominy, might not launch a devastating blow against Richmond. It was not until the next morning that he felt sure that McClellan was pulling back to the James River to change his base. On the 29th Lee’s plan called for Magruder, with strong support from Jackson, to attack the rear of Union forces retreating toward the James and force McClellan to stand and fight. Meanwhile, A. P. Hill and Longstreet were to move rapidly across the Confederate rear from the left (northern) flank to the right (southern), where they would hit the head of the Union column marching toward the James. Again, Lee’s plans went awry. Jackson failed to appear. Magruder’s attacks amounted to little more than skirmishing. Hill and Longstreet managed to cover the eighteen miles to put themselves close to the head of the retreating Union forces, but they were not yet in position to launch effective attacks. Nevertheless, the pressure of Confederates hanging on his rear forced McClellan to abandon the hospital at Savage Station with its 2,500 wounded.

On the 30th, matters proved more favorable for the Confederates. By that point Lee had five divisions south of the White Oak Swamp, positioned to attack the head of McClellan’s army, while Jackson could hit the retreating Union forces north of the swamp. A. P. Hill and Longstreet would direct the main blow, one which Lee aimed to break the Union column so that the Confederates could defeat the Army of the Potomac in detail. Brigadier General Benjamin Huger was supposed to begin the attack in the center to the left side of the main attack. But busily engaged in chopping their way through the tangled growth of southern Virginia, because the Federals had obstructed the road he was to take, Huger and his men failed to reach their attack position until midafternoon. When Huger finally ran into Brigadier General Henry Slocum’s outnumbered division, he fired a few artillery shells and then retired.

Meanwhile, Brigadier General Theophilus Holmes’s division, the southernmost of the attack, ran into serious opposition. Approaching Malvern Hill, Holmes’s division spied large numbers of Union troops crossing the hill. After siting his division’s artillery, he proceeded to open up a bombardment. That proved to be a serious mistake, because superior Union artillery on the hill, as well as the massive artillery pieces on Union gunboats in the James, blasted the Confederate attackers. Union naval power once again proved its value. Meanwhile, at the rear of the Union column, Jackson did little more than count prisoners, write to his wife, and take a nap. The course of the fighting over the Seven Days battle proved the most unsatisfactory of Jackson’s career. At least Huger’s skirmishing made enough of a racket to alert Longstreet that it was time to launch the main blow. It was Lee’s last hope of dividing the Union army, but it had no chance of success. Longstreet and Hill launched a series of stand-up attacks against four Union divisions, all of which failed dismally. The Confederates did manage to capture eighteen Union guns and a few prisoners, but achieved no substantial tactical success at the cost of 3,500 casualties.

What happened next had a great deal to do with the frustrations that had beset Lee over the past six days as he had watched his subordinates botch his plans. By morning on 1 July, the Union commanders had entrenched a massive array of artillery on the slopes of Malvern Hill. Two corps under Porter and Keyes had deployed their infantry among the artillery, while the corps of Heintzelman and Sumner were in immediate support. Early that morning, warned by D. H. Hill that it would be dangerous to attack the hill, Longstreet (reflecting his commander’s own attitudes) had casually replied: “Don’t get scared, now that we have him whipped.”14 Lee and Longstreet were right in terms of McClellan, who would spend the day on a gunboat in the river, but he was wrong in referring to the soldiers of the Army of the Potomac. The opening stage of the battle involved the Confederates attempting to set up their artillery to suppress the Union batteries on the hill. That effort failed almost before it began, but what followed was a disaster. Three Confederate divisions, D. H. Hill’s, Huger’s, and Magruder’s, moved out into the open and attempted to attack up the slope of the hill, and Union defenders slaughtered most. By the time it was over 5,500 Confederates were dead or wounded.

Nevertheless, in spite of the heavy casualties the Army of the Potomac inflicted on the attacking Confederates at Malvern Hill, McClellan failed to authorize a counterattack. Instead, he ordered a retreat back to Harrison’s Landing. One of the most interesting soldiers among the generals in the Army of the Potomac was Philip Kearny. As a youth, he had wanted to attend West Point and become a soldier. However, his guardian grandfather, one of the richest men in New York, had forbidden such a career and shipped his grandson off to Columbia to prepare for a career in the law. But his grandfather died, and Kearny joined the army. His performance in the Mexican War was outstanding, although he lost an arm. After resigning his commission, he served in the French Army with distinction at Solferino, where he won the Légion d’honneur. Now as the Union army retreated from its victory, he made a devastating, but all too accurate, comment on McClellan’s leadership: “I, Philip Kearny, an old soldier, enter my solemn protest against this order for retreat. We ought instead of retreating should follow up the enemy and take Richmond. And in full view of all responsible for such declaration, I say to you, such an order can only be prompted by cowardice and treason.”15 Even Porter, McClellan’s most loyal subordinate, considered the retreat a mistake.

The irony of the Seven Days battles was that, while Lee had bested McClellan psychologically in every way, the Confederates had still failed to destroy the Army of the Potomac. While the morale of that army’s soldiers had suffered a severe shock, it was not permanently shattered. In addition, the casualty figures for the fighting represented a burden that, in the long run, the Confederacy with its smaller population and more limited resources could not bear. In the Seven Days battles, Union casualties were 15,855 with 1,734 dead, 8,066 wounded, and 6,055 missing including those captured. On the other hand, Confederate losses were 20,204 with 3,494 killed, 15,758 wounded, and 952 missing (most dead).

To all intents and purposes, by July 1862 with the conclusion of the Peninsula Campaign, McClellan had set the Army of the Potomac’s command culture. That culture, largely formed by the Old Army’s attitudes—rigid obedience to orders, a general lack of initiative and aggressiveness, an emphasis on date of rank, and an unwillingness to cooperate—would dominate the Army of the Potomac long after McClellan had left its command in November 1862. When Grant arrived in the East to take command of all the Union armies in spring 1864 he was to discover that culture still in place, and it would take the costly battles in Virginia for him fully to realize how different the Army of the Potomac’s culture was from that with which he was familiar in the West.

Second Bull Run

The incompetence of Union generals in chasing Jackson back and forth across the Valley finally persuaded Lincoln that he and Stanton could not run the war from Washington. Thus, in late June they brought Major General John Pope from the West to assume control of the northern Virginia theater, and to command what was now to be called the Army of Virginia. Politically, Pope possessed excellent connections. In the West he had achieved a measure of success in capturing Island No. Ten in the Mississippi with no casualties. He had then commanded one of the wings in Halleck’s tortuous advance on the railroad center of Corinth, Mississippi. But Pope had not distinguished himself against first-rate opponents. He was bombastic and aggressive, but at least Shiloh’s casualty bill had not tarnished his reputation.

In retrospect, that bloodbath may well have saved Grant from a transfer East, where the culture of the Eastern armies could have destroyed his future usefulness to the North. Instead, Grant remained in the West, where he would grow into a formidable commander and strategist. Pope arrived in Washington at the end of June 1862. The War Department promulgated his new command on 26 June, which consisted of what had hitherto been three separate commands, led by as unimpressive a group of senior officers as the Eastern armies possessed: Franz Sigel, Nathaniel Banks, and Irvin McDowell. The first two were politicians and well connected, which explains why they were to hang around for another two years, while McDowell was an unimaginative regular officer who had displayed little skill thus far in the war. Sigel claimed some training in the army of the princedom of Baden, Germany, where he had participated in the Revolution of 1848. However, none of that experience had imparted the slightest battlefield wisdom. Banks’s prewar experience had been in Massachusetts politics, which, whatever its combative nature, had not prepared him for war. The troops McClellan took to the Peninsula and which became the core of the Army of the Potomac inherited many of its chief’s flaws, but it did possess a strong esprit de corps and corporate identity. Unfortunately, that same sense of camaraderie suppressed, as we shall see, any desire on the part of McClellan’s forces to cooperate with Pope.

Instead of attempting to pull his new command together, Pope spent most of July politicking and hobnobbing with Washington’s elite. He strongly recommended the administration bring Halleck to Washington as the army’s general in chief, a position McClellan had held until his demotion in March 1862. Pope’s efforts coincided with Lincoln’s belief that he and Stanton needed sensible military advice. They ordered Halleck to Washington, and on 23 July, that general assumed the position of commander of Union armies. One recent author has described Halleck in the following terms: “Beneath the dome of his high forehead, the general would gaze goggle-eyed at those who spoke to him, reflecting long before answering and simultaneously rubbing both elbows all the while, leading one observer to quip that the great intelligence he was reputed to possess must be located in his elbows.”16 Lincoln later accurately described Halleck as the army’s chief clerk.

While in Washington, Pope issued a proclamation to his soldiers that infuriated McClellan and most of the senior officers in the East. He deliberately aimed at that result: “Let us understand each other. I have come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies; from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary and to beat him when he was found; whose policy has been attack and not defense.”17 Such hubris proved a terrible mistake, not necessarily because it annoyed McClellan, Porter, and their ilk, but because it forced Pope to act too aggressively when confronting Lee. In addition, the commander of the Army of Virginia issued General Order No. 5, which provided his troops with carte blanche to live off the countryside. That order outraged the Confederates, but it did have the beneficial result of stripping the countryside of northern and central Virginia bare, thus creating a logistical burden on the Army of Northern Virginia.

Halleck’s arrival in Washington heralded a fundamental shift in Union strategy. One of his first acts was to visit McClellan, who had hunkered down on the Peninsula after his humiliation of the Seven Days battles. McClellan argued that he needed extensive reinforcements if he were to resume the offensive against Richmond, but Halleck warned that, considering other commitments, he could only provide 20,000 troops. McClellan indicated that would suffice. But upon Halleck’s return to Washington, McClellan telegraphed that he required 50,000 more troops to resume the offensive. That was enough of McClellan’s obfuscation for Halleck. On 4 August the army’s new general in chief, with Lincoln’s support, ordered McClellan to pull his army from the Peninsula and return it to northern Virginia. Up to this point the Army of the Potomac had been holding Lee in front of Richmond. Admittedly, Lee had already released Jackson with 12,000 men to protect the railroad junction and supply depot at Gordonsville. Then, on 27 July, he added A. P. Hill’s division of 13,000 to Jackson’s command, perhaps influenced by the fact McClellan remained quiescent. Nevertheless, the bulk of Lee’s army still faced Union forces on the Peninsula.

However, once McClellan’s army began returning to Washington, Lee, with a shorter distance to reach the Rappahannock, could reposition his army more quickly to northern Virginia than the Army of the Potomac could make the move, especially under McClellan’s dilatory leadership. Having received the order to abandon the Peninsula, McClellan waited no less than ten days before the first units of the Army of the Potomac clambered on board steamboats to head down the James River. As he wrote his wife on 10 August, “I have a strong idea that Pope will be thrashed … such a villain as he is ought to bring defeat upon any cause that employs him.”18 Beyond the normal snail’s pace characterizing the Army of the Potomac’s movements, it appears McClellan and his subordinates did everything they could to insure Pope would fight Lee on his own. Whether their actions were the result of deliberate malfeasance or incompetence is difficult to say. As of 18 August, two weeks after receiving the order to withdraw from the Peninsula, McClellan had not moved a single soldier beyond Fort Monroe at the Peninsula’s tip.

But the true author of John Pope’s misfortunes was the general himself. He was one of those officers who knows everything and so refuses all advice or intelligence that contradicts his assumptions. On 9 August Jackson moved. Hearing that Banks’s corps was in the vicinity of Culpeper, Jackson struck north from the Rappahannock. For once he found himself surprised, when Banks attacked first. After several hours of tough fighting, Jackson launched Hill’s division against the Union flank and drove the outnumbered Banks off the field. By the time it was over, Union losses totaled 2,353, while the Confederates suffered 1,000 fewer casualties. Nevertheless, Jackson, lacking the strength to withstand Pope’s full strength, retreated back behind the Rappahannock. The battle achieved little, either in an operational or strategic sense, but psychologically it put Pope on notice the Confederates were in strength on his front.

By 7 August Lee was piecing together an intelligence picture that suggested McClellan was about to withdraw from the York Peninsula. A week later he was sure. Longstreet moved with ten brigades to Gordonsville; Stuart with his cavalrymen also moved to that junction, while Anderson’s division, which held Drewry’s Bluff, eventually followed. Lee was bringing north over 30,000 men to link up with Jackson. The Confederate commander’s express aim was to destroy Pope before McClellan returned to northern Virginia. Unlike its opponents, nearly everything in the Army of Northern Virginia was done with snap and speed—especially since Lee had reorganized the army after the Seven Days battles to remove commanders he found wanting. On 15 August Lee arrived at Gordonsville to confer with his chief subordinates. Out of that meeting emerged one of the boldest campaigns of the Civil War.

In mid-August the Army of Northern Virginia was spread out between Gordonsville and the Rapidan River, while much of Pope’s Army of Virginia lay between the Rapidan and Rappahannock. Early morning on 18 August, Pope encountered one of the few pieces of luck he received during the campaign. During the night, the Confederates had neglected to picket Raccoon Ford on the Rapidan, and a Union cavalry raid waltzed in and hit Stuart’s headquarters. Stuart escaped, but the Union troopers captured orders indicating Lee was up on the Rapidan and intended to smash the Army of Virginia. Pope immediately moved his troops out of danger by retreating across the Rappahannock. Meanwhile, in preparation for the advance north, Jackson decided to instill additional discipline in his troops. He had three deserters brought in, tried by drumhead court-martial, and sentenced to death. When one of their officers interceded on behalf of two of the men, Jackson announced: “Sir! Men who desert their comrades in war deserve to be shot!—and officers who intercede for them deserve to be hung!”19 Jackson then had his divisions formed up on three sides of a square. The miscreants were led out by their own companies, which acted as executioners. After proper pronouncements, they shot the malfeasants.

Thwarted in the effort to destroy Pope between the Rapidan and the Rappahannock, Lee opted for a truly risky strategy. Time was slipping, and despite McClellan’s best efforts, it was clear the Army of the Potomac would arrive in northern Virginia in the near future, which would weigh the correlation of forces heavily against the Confederates. On 24 August, after conferring with Jackson, Lee split the army in half and launched Jackson on a deep sweep behind Union lines to strike at the Orange & Alexandria Railroad and Pope’s logistical depots. Lee explicitly ordered Jackson not to bring on a general engagement, but rather to entice Pope forward, thus lengthening the time before his troops could combine with the Army of the Potomac. The risk Lee was taking was greater than risks he would take the next year at Chancellorsville, because nearly sixty miles would separate the two halves of his army. As had occurred in the past and would occur in the future, Lee was counting on the lethargy of Union commanders and the sloppiness of their reconnaissance.

Well before dawn on 25 August, Jackson’s foot cavalry were marching to the northwest, a march that took them to Orlean and Salem, before they turned east to follow the roadbed of the Manassas Gap Railroad. By early evening the lead soldiers of Richard S. Ewell’s division arrived at Salem after a twenty-five-mile march. Jackson’s last units straggled in at midnight. Thus, Jackson had positioned his force approximately twenty miles from the Orange & Alexandria Railroad. Sigel on the far right of the Army of Virginia apprised Pope that a major Confederate movement had passed by his troops to the west, headed northwest. Pope, who throughout the campaign displayed an eagerness to believe the enemy was doing what was convenient to his plans, dismissed the threat in his belief Jackson was returning to the Shenandoah. Before dawn on the 26th Jackson headed his troops through Thoroughfare Gap in the Bull Run Mountains, the ridge running east of the Blue Ridge. Meanwhile, Longstreet kept Pope’s attention focused on the Rappahannock.

By 1600 on the 26th the Confederates had reached Gainesville less than five miles from Bristoe Station. Sending Ewell’s division and Stuart’s cavalry ahead, Jackson struck at one of the main transportation centers for Pope’s army. Smashing up trains and destroying the rails, the Confederates had a field day. The real prize, however, was five miles farther up the tracks at Manassas Junction, which served as the Army of Virginia’s main supply base. Guarded by a few infantry and Union cavalry, who had never seen combat, Manassas Junction too soon fell into Confederate hands. In a march of over fifty-four miles in thirty-six hours, Jackson had wrecked trains, disrupted the Army of Virginia’s supply system, captured immense stores, which fed his weary troops for the next week, and thoroughly embarrassed Pope. Most importantly, Pope had lost control of the campaign. Jackson pulled back as soon as his troops had packed their blankets with everything portable and disappeared toward the northwest; what the Confederates could not carry, they destroyed. The purpose of the raid, however, had not been to wreck Union logistics, or to gather in loot, but rather to draw Pope’s Army of Virginia into a major fight before McClellan arrived. In fact, Jackson’s humiliating success had done everything necessary to set the stage for the drama Lee set in motion.

Believing Lee had divided the Army of Northern Virginia, Pope set off in pursuit of Jackson. For the next week he focused almost exclusively on Jackson, as if Lee and Longstreet did not exist. Pope even boasted to his staff that he was going to bag Jackson’s entire force. Meanwhile, Porter’s V Corps had already arrived at Aquia Creek and was moving to Kelly’s Ford on the Rappahannock. Porter brought little except his outstanding troops. He had proved on the Peninsula that he could fight when pressed, but like his beloved chief, McClellan, he would take no risks for John Pope, whom he deeply distrusted. Halleck was supposed to try to coordinate the movements of Pope and McClellan, but, of course, he did nothing of the kind. By now Heintzelman’s III Corps was also arriving with two of the best division commanders in the Army of the Potomac, Hooker and Kearny. The latter would characterize his corps commander with this scathing description: “His small quanteen [sic] of brains have been fossilized by near 40 years of small garrison routine at the head of 100 foot, in some western outpost.”20

Meanwhile, Pope had no idea of Jackson’s location. On 27 August, the Union general ordered his army to march on Manassas in hopes of catching the Confederates. But as Pope and the Army of Virginia marched north, while Jackson disappeared seemingly into the mists of northern Virginia, Longstreet was also marching. The crucial area through which he had to move was also Thoroughfare Gap. Had Pope paid attention to the larger framework within which operations were unfolding, he would have made an effort to insure that sufficient Union troops held the gaps through the Bull Run Mountains. McDowell did warn Pope of the danger of not reinforcing the gaps, but the Union commander again paid no attention. Thus, Longstreet pushed the relatively weak Union force aside in moving through the gap.

Jackson awaited the Union attack with the calm of a general who had great confidence in himself and his troops. Pope’s search finally ended in success. Late on 28 August, Major General Rufus King’s division found the Confederates ensconced north of Groveton on the Warrenton Turnpike, not far from the old Bull Run battlefield. In fact, it was Jackson who found them, for after studying the Union column, he ordered his troops to attack from their shelter in the woods north of the turnpike. From the Union perspective, it was an encounter battle, in which both sides steadily fed in regiments. From the Confederate point of view, it was a matter of keeping Pope’s attention centered on the fight until Longstreet arrived. The arrival of two regiments from Abner Doubleday’s division allowed Union forces, despite their being outnumbered nearly two to one, to fight Jackson to a stalemate.

By evening the fighting was dying down. In spite of the gathering gloom, Jackson ordered his troops to launch one last attack. It was no more successful than the initial engagements, but substantially added to the number of Confederate casualties. Overall on the 28th, the Union probably had the advantage in the casualties. But that was not what mattered. During the night, as King’s division abandoned the battlefield, other Union forces were on the way. What mattered was that Pope’s attention now centered on Jackson. During the night he issued orders to concentrate Union forces to the west of Manassas near Groveton. The fighting on the 29 August underlined his inability to concentrate on the larger operational framework, or the nature of his enemy. Sigel’s corps was closest to Jackson, and both he and Kearny, located to the west of Centreville, received a demand from Pope to attack immediately. Kearny, who was as sick of Pope as he was of McClellan, exploded: “Tell General Pope to go to Hell. We won’t march before morning.”21 Disastrously Pope deluded himself that Jackson was retreating, while at the same time he paid no attention to Longstreet’s ominous approach.

Jackson deployed his three divisions along an uncompleted railroad cut, which its builders had abandoned. Swinging from the northeast, it crossed Bull Run Creek and then ran in a southwesterly direction, paralleling the Warrenton Turnpike. Behind the unfinished embankment, Jackson stationed A. P. Hill’s division, his strongest, on the left, because that position held the key fords over which the Confederates would have to retreat, if Pope pushed too hard. Two brigades of Ewell’s division held the center, behind the embankment, while Brigadier General William Starke’s division held the right. By itself, the position was not innately strong, but the terrain, broken up by woods and ravines, made it difficult for Union commanders to control their troops in the heavy fighting.

Sigel’s corps began the fighting on the 29th by attacking Hill’s positions along the railroad cut on the left (northern) portion of Jackson’s deployment. After enjoying an initial success as the Union attack ran into Confederates on the eastern side of the railroad cut, it collapsed when its troops hit the well-protected Confederates behind the embankment. Had Jackson wanted to launch a major attack, Hill’s division was in a position to wreck Sigel’s corps, but Jackson was waiting for Longstreet’s arrival. The division of the German expatriate Carl Schurz bore much of the fighting. For a moment there appeared an opportunity to break through Hill’s division, but Kearny, who bore a grudge against Sigel, refused to cooperate and failed to support the first attack. Unfortunately, Sigel dispersed the arriving support from Reno’s and Heintzelman’s corps in higgledy-piggledy fashion, so that by afternoon, the organization of the three Union corps on the battlefield had broken down. That made command and control of the corps difficult, if not impossible, for the remainder of the battle.

At 0800, a courier arrived at Jackson’s headquarters with the report that Lee and Longstreet were only several hours from the field. Stuart, who had been up with Jackson during the raid, now made contact with Lee to guide Longstreet’s troops onto Jackson’s southern flank. As he returned to Jackson, Stuart spied the dust cloud raised by a large Federal force approaching the left (south) of the Union line and Jackson’s right. It was Porter’s V Corps, but the Confederates had no idea of the strength of the Union force except that it was large. Stuart immediately deployed skirmishers, while his cavalry stirred up dust to indicate that large numbers of Confederates were in front of Porter’s line of advance.

That action was sufficient to stop Porter and allow Longstreet to complete his arrival. According to Pope’s orders, he was supposed to pile into Jackson’s right flank. Instead Porter stood frozen, hanging to the southeast of Longstreet’s deploying troops. Nevertheless, the V Corps was in a position to attack Longstreet’s Confederates, should they attempt to attack Pope’s southern (left) flank. Thus, the mere presence of the V Corps southeast of the battlefield forced Lee to hesitate in committing Longstreet’s divisions to the fight. Admittedly, Porter failed to attack Jackson’s flank, and for both this failure and the sin of his indiscreet politicking with conservative Democratic politicians, Porter would find himself court-martialed and cashiered after Antietam. Due to his able service during the Seven Days battles, and Pope’s own self-inflicted errors at Second Bull Run, it was an unfair decision in purely military terms. Nevertheless, Porter had exposed himself to Radical Republican wrath, which sought to make an example of a member of McClellan’s clique.

While Longstreet drove his troops on the road northeast from Thoroughfare Gap at a furious pace, another major corps of the Army of the Potomac was available to reinforce the Army of Virginia. On the 27th, late in the afternoon, McClellan informed Halleck that Franklin’s VI Corps was ready to march. Nevertheless, although he received three direct orders for the corps to march to Pope’s aid, twenty-two hours later McClellan telegraphed Halleck to report the troops might be ready to march the following morning on the 29th. Franklin’s VI Corps finally marched at 0600 on the 29th, but only managed to crawl forward ten miles. On the 30th, the VI Corps reached Centreville after a march of only twelve miles. McClellan’s correspondence throughout the period suggests a general willing to allow his countrymen to die to promote his own position. On the 29th, he telegraphed Lincoln: “I am clear that one of two courses should be adopted—1st To concentrate all our available forces to open communication with Pope—2nd To leave Pope to get out of his scrape & at once use all our means to make the Capital perfectly safe.”22 As a highly decorated marine officer suggested to us, it is enough for one to wish he could reach back in time and strangle the “dishonest, pusillanimous son of a bitch.”

What was Pope doing on the 29th? Until the early afternoon, Sigel had handled the fighting in his usual disorganized fashion. Pope arrived in the early afternoon, while his rambling, incoherent orders, written at 1000 on the 29th, indicate he believed that Longstreet “is moving in this direction at a pace that will bring them here by to-morrow night or the next day.”23 In fact, Pope wrote those orders almost at the moment when Longstreet’s troops were deploying on Jackson’s southern flank. But Pope was a stubborn man, and in spite of repeated warnings from those on his southern flank, he held to his faulty assessment. He now launched a series of attacks on Jackson. Moreover, much as McClellan was to do at Antietam three weeks later, these attacks went in individually, allowing the Confederates to respond to each. The first came from one of Hooker’s brigades under Brigadier General Cuvier Grover, which achieved a signal success when its attack uncovered a hole in Jackson’s lines. But Grover failed to receive support, and the Confederates quickly closed up. Similarly, an attack by John Reynolds’s division on Jackson’s right (southern) flank failed. But Reynolds did discover, lying beyond his final position, masses of Confederate infantry, undoubtedly Longstreet’s, farther to the southwest. Pope simply dismissed the warning that one of Reynolds’s staff officers brought him: “You are excited, young man; the people you see are General Porter’s command taking position on the right of the enemy.”24

The next Union attack again gained initial success but after pushing across the unfinished railroad embankment collapsed under counterattacks on its flanks. Because of the failure to provide supporting troops, each brigade-sized attack inevitably failed against Jackson’s veterans. The collapse of Colonel James Nagel’s brigade for a time opened a hole in the Union center, but Jackson was still playing for time. By now Pope was thoroughly annoyed that Porter had yet to launch his attack on Jackson’s right. At 1630, he issued another set of orders, directing Porter to attack Jackson’s right. At the same time, he ordered Kearny, who had contributed little thus far, to attack the Confederate left, which had been under pressure all day. Kearny struck with his full division of nearly 3,000 men and put heavy pressure on Hill. For a time, it appeared the attack would break through Jackson’s left, but Kearny had only one division, while Jackson had three. Thus, he was able to throw Jubal Early’s brigade, one of his largest and best, into the fight. It was more than enough to break the Union attack.

The final fighting of the day came when Lee ordered Hood’s division forward to set the stage for the next day’s fight. Hood’s men ran into John Hatch’s smaller division in the twilight. Pope and McDowell had ordered Hatch to attack, because the two believed the Confederates were retreating down the Warrenton Turnpike. Nothing could better underline their flight from reality. One of the great failings of incompetent generals lies in their penchant for attempting to adapt the real world to their preconceived notions, rather than adapting their assumptions to reality. Both Pope and McDowell paid for that inability to recognize reality with their reputations. Their soldiers paid with their lives.

Pope still had the opportunity to pull back to Centreville in the night and wait for the rest of the Army of the Potomac to arrive. The evidence certainly indicated Longstreet had arrived and Lee had united his army. But convinced that Longstreet remained at least a march away and that Jackson was on the brink of retreating, Pope stood his ground. On the other side of the hill, Lee and Longstreet considered continuing Hood’s attack during the night, but their subordinates, including the always aggressive Hood, talked them out of such a move. Instead, Lee decided to await Pope’s first moves the next day, before launching the kind of slashing attack that had already made the Army of Northern Virginia famous during the Seven Days battles fighting.

Well past midnight, Richard Anderson’s division of some 6,000 soldiers, whom Longstreet had left behind to cover the Rappahannock, reached the main army. Unlike Franklin’s VI Corps, which could barely make ten miles a day, Anderson’s division covered over twenty miles a day, the last segment in seventeen hours of marching. As Lee waited for his opportunity, Pope dithered. At 0700, he met with his senior officers. They warned that the Confederates were not retreating; they also argued that the best option was to launch a better-coordinated and larger assault on Jackson’s left, given Kearny’s temporary success the evening before. But having agreed with them, Pope issued no orders. Instead, he and his confidant McDowell, according to a staff officer, “spent the morning under a tree waiting for the enemy to retreat.”25 The most reasonable explanation is that the two generals still believed the Confederates were retreating in spite of the evidence. On the other side, Lee expected Pope would make the mistake of attacking Jackson again and that an opportunity would arise for Longstreet to attack Pope’s southern flank.

In the early morning hours of the 30th Porter, having pulled back from his position on Longstreet’s flank, had finally arrived with his V Corps. Along the way he also lost one of his divisions, which wandered off to Centreville and spent the day acquiring new shoes from supply dumps. Into the early afternoon, Pope persisted in his assumption the Confederates were not in strength on his southern flank. He would only send a single brigade to reinforce Reynolds’s division, which had deployed on Chinn Ridge to guard the Union flank in front of Longstreet’s masses of infantry and artillery. Meanwhile, Pope finally ordered Porter to attack with the V Corps and its 10,000 men against Jackson’s right. As the attack would go in against Starke’s division, it would not only strike relatively fresh troops but would also expose its flank to enfilade fire from a portion of Longstreet’s and S. D. Lee’s artillery battalions. Moreover, Pope ordered no supporting attacks to distract Confederate attention.

The result was predictable. Starke’s division was fully prepared. Almost immediately, Confederate artillery fire hit Porter’s attack from enfilade positions and inflicted devastating casualties. It was a turkey shoot. Nevertheless, some of Porter’s men came close to breaking through Starke’s position, but as had been the case throughout the battle, Union commanders, in this case Porter, refused to reinforce success. The fighting was as fierce as anything yet seen on the field of Second Bull Run. One Union soldier recounted: “Regiments got mixed up—brigades were intermingled—all was one seething, anxious, excited mass. Men were falling by scores around us, and still we could see no enemy. … Some officers were yelling ‘Fire!,’ others were giving the command, ‘Cease fire, for God’s sake! You’re shooting our own men!’”26 The attack collapsed into a rout that, for a moment, spread disorder to the center of the Union line.

At this point McDowell intervened. Seeing the disorder caused by Porter’s collapse, he ordered Reynolds’s division to leave its position on Chinn Ridge and move to reinforce the V Corps’ badly shaken troops. He thereby reduced Union forces standing to the east of Longstreet’s massed divisions to two brigades. It was the single most incompetent decision made during the battle and reflected the fact that this late in the battle McDowell, like Pope, still believed Longstreet had yet to link up with Jackson.

Shortly after 1600 Lee and Longstreet struck. Even then Pope failed to recognize the gravity of the situation. McDowell, however, immediately recognized the disaster that confronted the Army of Virginia. Hood’s division stepped out of the woods to the west of the Union position with his brigade of Texans leading the way. Longstreet’s attack hit the Union flank with the full power with which Hood’s Texans and assorted other Confederates were capable. Following to the right of Hood’s division and slightly behind them were the men of James L. Kemper’s and D. R. Jones’s divisions. Only four Ohio regiments and a single battery of Union artillery held Chinn Ridge against the mass power of Longstreet’s attack. As Longstreet advanced, Pope finally awoke to the reality that the Confederates were in strength on his exposed flank in a position to destroy the Army of Virginia. It was now a desperate matter of moving sufficient troops onto Henry House Hill, and to do that, the Ohioans were going to have to mount an effective defense of Chinn Ridge, which is precisely what they did.

The Confederates helped. Disordered by the staunchness of the Union stand and the bombardment of Union artillery from the left of Pope’s position, they launched a series of attacks that initially failed. The Union position on Chinn Ridge finally collapsed when Kemper’s division caught up with Hood’s men. Leading the charge that eventually swamped the Union defenders was the commander of the 7th Virginia, Colonel W. T. Patton, grandfather of General George Patton. Eventually, the overwhelming Confederate numbers swamped the Ohioans and they collapsed, but they had taken a heavy toll of their attackers, and perhaps more importantly, they had bought time. As the Ohioans broke, two more Union brigades, rushed over from Sigel’s corps, joined in the fight. They, too, went down to defeat, but not before adding to the swelling Confederate casualties. The defenders suffered just as heavily, their most famous casualty the eldest son of Daniel Webster. It was not until the Confederates had broken them that the Stars and Bars flew over the ridge.

While the Ohio regiments were fighting and dying, Pope, McDowell, and Sigel scrambled to mount a makeshift defense along Henry House Hill. If successful, defense of that position would keep the Warrenton Turnpike open, which would provide the Army of Virginia a route to retreat. Should they fail, the Confederates would gain control of the turnpike and be in a position to destroy Pope’s entire field army. One of the key elements in Lee’s plan, which might have achieved that aim, was for Jackson to mount major attacks to hold the Union center and right (northern) divisions in place. But as in the Seven Days battles, Jackson remained largely quiescent. Thus, the fighting that day was in Longstreet’s hands.