The War in the East, 1863

Yet a small remnant remained in desperate struggle, receiving a fire in front, on the right and on the left, many even climbing over the wall, and fighting the enemy in his own trenches until entirely surrounded; and those who were not killed or wounded were captured, with the exception of about 300 who came off slowly, but greatly scattered, the identity of every regiment being entirely lost, and every regimental commander either killed or wounded. … The brigade went into action with 1287 men and about 140 officers … and sustained a loss … of 941 killed, wounded, and missing.

—Edward Porter Alexander, Military Memoirs of a Confederate

The turn of the year into 1863 represented the nadir of the North’s fortunes. In the east Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had just humiliated the Army of the Potomac in the murderous Battle of Fredericksburg. In the West Grant and Sherman had failed in their efforts to attack Vicksburg—the former was forced to retreat back to Memphis after Confederate cavalry raiders had cut his supply lines, while Sherman’s attack on Chickasaw Bluffs in front of Vicksburg was no more successful than most such frontal attacks. And in central Tennessee, Union forces, having beaten back Bragg’s offensive into Kentucky, remained stalled.

For Lincoln, who saw matters clearly, the purpose of Union armies was to fight, a reality that McClellan and all too many Northern commanders had failed to grasp. The president had recognized early in 1862 that the clearest path to victory lay in Union armies pressing the Confederacy from all sides. At least McClellan had been relieved first as commander of Union armies and then as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Nevertheless, his replacement at the top of the military pyramid, Halleck, was hardly an improvement, functioning more as a clerk than director of the Union’s military strategy, when he was not bombarding commanders in the field with senseless instructions or even undermining their capacity to fight. Thus, there would be no coordination of the Union offensives in 1863.

It was in the east that Lincoln confronted the most serious difficulties. The Army of the Potomac’s morale had reached its lowest point by January 1863. Fredericksburg, along with Burnside’s appalling mismanagement and terrible leadership, was undermining the army’s soul. Pay was in arrears as much as seven months; soldiers were subsisting on hard tack and salted meat; uniforms were in tatters from the fierce campaigning of the previous year; and, most distressing of all, a significant number of officers had gone home with or without leave, abandoning their men to their own devices. To cap this dismal situation, a cabal of senior officers was working to undermine Burnside’s position and bring McClellan back as the army’s commander.

Lincoln would have none of that. “Little Mac” had thoroughly discredited himself in the president’s eyes with his unwillingness to fight. On 26 January 1863, the president acted. He chose “Fighting Joe” Hooker, who had proven himself to be one of the more aggressive corps commanders in the army. However, he was not popular among his peers. He had a dubious reputation as a drinker and womanizer, in other words, an individual who stood outside the staid moral standards of the time. In particular, he had a long-standing quarrel with Halleck that went back to their California days in the Old Army. So deep was the antagonism between the two that when Lincoln appointed Hooker to command the Army of the Potomac, the general requested that he only deal with the president and have nothing to do with Halleck, a command relationship which was to exercise a baleful impact on the spring campaign. But at least Hooker had earned his nickname on a number of battlefields. However, he had also declaimed to the New York Times’s correspondent with the Army of the Potomac that the country needed a dictator. After Lincoln made the momentous decision to appoint Hooker, he wrote the general a letter that put the president’s cards on the table: “I have heard, in such a way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it is not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship.”1

Hooker immediately tackled the Army of the Potomac’s administrative and logistic difficulties. With the administration’s help, he cleaned house: he relieved Sumner and Franklin and divided Burnside’s old command, the IX Corps, with one division under William “Baldy” Smith sent off to the Peninsula and two divisions deployed west to reinforce Union forces in Kentucky. In the East, Hooker persuaded the administration to relieve him of responsibility for protecting the capital with that duty turned over to Heintzelman, under whom Hooker had served as a division commander. In terms of unintended effects, while the IX Corps achieved little on the Peninsula, its movement alarmed the Confederates. Lee moved Longstreet and two divisions to watch Union forces in the area and ensure the latter did not interfere with the Confederacy’s north–south communications or threaten Richmond. Thus, the Army of Northern Virginia faced Hooker with only two of its three corps when the Army of the Potomac moved south in early May.

Hooker also straightened out the administrative and supply mess Burnside and others had created. Whatever Hooker’s weaknesses, he was a superb administrator. He solved the desertion problem through a reimposition of discipline and security measures that made it more difficult for soldiers to leave their units without permission. At the same time, he instituted a furlough policy that allowed soldiers leave to return home for short periods. Rations almost immediately improved, including fresh vegetables and soft bread in place of hard tack. Hooker received considerable help from a logistical system organized and run by two of the unsung heroes of the war, Herman Haupt and Daniel McCallum, first-class railroad men. Here, in sharp contrast to the Confederacy’s situation, the North’s railroad infrastructure supported the front at the same time that it kept the Northern economy running at full speed. By late winter, Hooker had restored the Army of the Potomac’s discipline and pride. For that contribution alone he deserves a place as one of the war’s more significant generals.

Hooker also carried out a thorough reorganization of the army’s command structure. His most important move was to concentrate the cavalry into a separate branch. Through January 1863, the Army of the Potomac had assigned its cavalry regiments higgledy-piggledy to the various corps and divisions. However, while the creation of a cavalry command represented a major step forward, Hooker made the mistake of appointing Major General George Stoneman to command the new force. Stoneman was the worst sort of Army of the Potomac general officer, brave, but devoid of imagination, initiative, and the capacity to adapt to unforeseen circumstances. The change in the Union cavalry became apparent in mid-March when a force under Brigadier General William Averell caught Confederate Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry brigade by surprise and gave the Confederate troopers a bloody nose at Kelly’s Ford. Nevertheless, while the engagement was a tactical success, Averell botched the advantage of surprise and failed to wreck Lee’s brigade, which he was in a position to do. Again, the excessive caution that marked so much of the Army of the Potomac’s history reared its ugly head. Averell reinforced the disastrous penchant of Union subordinate commanders to await orders rather than display initiative by making clear that his regimental commanders were not to act unless they received explicit orders.

Hooker also made the significant mistake of stripping the army’s artillery chief, Brigadier General Henry Hunt, of much of his authority. In Hunt’s place he dispersed authority over the combat power of the army’s artillery arm, which was one of its most important material advantages over the Army of Northern Virginia, which suffered from comparative defects in both numbers of guns and ordnance. In terms of command of the various divisions and corps, Hooker confronted the difficult task of shuffling corps and division commanders to replace those killed or maimed in the fighting in 1862, or those whose incompetence had proved them incapable of serving in the field. The most important command shifts came with the corps commands. Major General Dan Sickles, a New York politician, infamous for having killed his wife’s lover and then having been found innocent on a plea of temporary insanity (Stanton was his lawyer), became the head of the III Corps as Hooker’s replacement. One of the other division commanders, O. O. Howard, complained that he had date of rank on Sickles. Hooker then appointed him commander of the XI Corps to replace Major General Franz Sigel, who had resigned his command in a huff. Howard was never to be popular with the German immigrants, who made up the great majority of the corps, partially because he was a religious do-gooder who passed out prayer books to the beer-drinking Germans. Howard would have a better war in the West in 1864 under Sherman, but he proved a disastrous choice for corps command in 1863.

South of the Rappahannock, Lee faced the problem of replacing a number of division and brigade commanders. He did possess three supremely talented subordinates to command his far larger corps: the steady Longstreet, the ferocious Jackson, and the mercurial Stuart, whose cavalry was organized formally as a division but acted as a corps. These were men on whom he could depend to display initiative, not only to see but also to capitalize on any opportunity. Lee’s problems were, not surprisingly, quite different from Hooker’s. Sending much of Longstreet’s corps south to watch the IX Corps and the approaches to Petersburg and Richmond relieved him of a considerable logistical burden. Quite simply, the South’s antiquated railroad system and its incompetent commissary authorities were incapable of keeping Confederate troops on the Rappahannock sufficiently supplied. Longstreet’s troops could correct some of the deficiencies of the supply system by foraging for themselves and their comrades to the southeast of Richmond. Nevertheless, by early spring rations in the army had fallen to four ounces of bacon and eighteen ounces of flour a day—hardly enough to keep body and mind together.

Whatever his supply difficulties, Lee, ever aggressive, was already thinking of launching the Army of Northern Virginia on another invasion of the North. He clearly hoped to achieve the decisive victory that had eluded him in 1862 and which, like Napoleon’s victories at Austerlitz and Jena-Auerstedt, he believed, would bring the war to an end. Nevertheless, he might have taken a lesson from Napoleon’s experience with multiple recurring wars. Regardless, he would have to wait for Longstreet to return and for the late spring with its grass to repair the famished condition of the horses in his command. Nevertheless, he was confident that Hooker and the Army of the Potomac would remain on the defensive, displaying the lack of initiative and drive that had so characterized that organization during the campaigns of 1862. His underestimation of his opponent would prove a serious miscalculation. Whatever his state of mind, Lee’s health had seriously deteriorated in March, when he suffered what appears to have been a mild heart attack. At fifty-six, Lee was long in the tooth for a Civil War field commander in contrast with Grant who turned forty-one in late April. Whether it was a heart attack or not, Lee continued to suffer attacks of angina, which makes his performance in the coming campaign that much more impressive.

By late April Hooker was ready to move. For one of the rare occasions in the war, the Army of the Potomac achieved surprise at the operational level against its nemesis. Hooker’s plan was straightforward: Stoneman’s massive force of nearly 10,000 cavalry would swing around Lee’s flank and drive deep into the Confederate rear, where its mission was to cause general mayhem: destroy the rickety rail lines (especially the bridges north of Hanover Junction on which Lee depended for his supplies), cut the telegraph lines, and intercept whatever supplies might move across the area’s road network. As soon as Stoneman moved out, a portion of the Army of the Potomac would execute a deception operation to suggest that Hooker was about to repeat Burnside’s disastrous attempt to break through the Confederate positions on Marye’s Heights overlooking Fredericksburg. At the same time, two corps would move under cover of night and the terrain to the northwest and cross the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford and then the Rapidan at Germanna Ford; a third corps would accompany them crossing at Kelly’s Ford and then Ely’s Ford. Two corps would be available as a swing force. If Lee fell for the deception, those corps would follow the move around Lee’s flank; if he did not and shifted swiftly to his left, they would be in position to take Fredericksburg from its undermanned Confederate defenders. It was a brilliant plan, and it caught Lee off guard. As the Southern artilleryman Porter Alexander noted: “On the whole I think this plan was decidedly the best strategy conceived in any of the campaigns ever set foot against us.”2

Nevertheless, to paraphrase Clausewitz, war is a simple matter, but its execution, more often than not, is exceedingly difficult. The layout of the Army of the Potomac’s winter quarters, resulting from the retreat across the Rappahannock after Fredericksburg, was such that its strongest corps lay to the east and along the river, where they were readily in sight of the Confederates. Any major movement of these units would alert Lee that something was afoot. Thus, Hooker could not use them to lead his outflanking move. Instead it would be Howard’s XI and Slocum’s XII Corps, followed by Meade’s V Corps, which would make the flanking move, the former two led by the least competent corps commanders in the Army of the Potomac. Moreover, the army’s system of seniority ensured that Slocum would be the senior officer leading the flanking move, while Sedgwick would be responsible for independent operations around Fredericksburg, in which the VI Corps would cross the river and persuade the Confederates that another major attack was coming on that front. Sedgwick, while beloved to his men, would prove congenitally incapable of independent command. Perhaps the wisest advice Hooker and Darius Couch, senior corps commander in the Army of the Potomac, received before the campaign was the president’s: “I want to impress on you two gentlemen in your next fight, put in all of your men.”3

Hooker expected much from Stoneman’s cavalry raid on Lee’s rear that was to initiate the campaign. Because it was an independent operation on which much depended, it is worth discussing its course before turning to the fight around Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg. Having done little to prepare despite being provided with thorough instructions, Stoneman gathered his forces at the last moment and ended up having to wait for the infantry corps to cross at Kelly’s Ford. Then having wasted most of 28 April in getting to the ford and crossing, he sat down as his official report records: “I assembled the division and brigade commanders, spread our maps, and had a thorough understanding of what we were to do, and where we were each to go.”4 One might have expected him to have accomplished the planning before the move began, admittedly a quaint approach in the Army of the Potomac. By being late Stoneman failed to screen the movement of the XI and XII Corps. As a result, a small Confederate raiding party captured prisoners from both corps, providing the first warning that a major Union move was afoot to the west of the main Confederate positions.

From that point, the Union cavalry raid moved at a snail’s pace. Stoneman divided his force, thereby decreasing its striking power. The portion under Averell moved a grand total of twenty-eight miles in the first five days of the campaign. At least that officer informed Hooker where he was, and Hooker curtly noted to the cavalryman that he did “not understand what you are doing at Rapidan Station.”5 On the 30th Stoneman managed to march the remainder of the raiding force a grand total of ten miles; one gets the feeling that infantry, led by a competent commander, could have moved faster. Stoneman’s subordinates proved even more cautious, swallowing supposed intelligence that Stonewall Jackson was immediately to their front.

Four days into their slow-motion raid, Stoneman’s troopers tore up five miles of the Virginia railroad, subsidiary to the movement of supplies to Lee. When Stoneman finally got around to attacking the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad, he did so below Hanover Junction, where Lee’s main supply depots lay, and then only inflicted minimal damage. Finally, Stoneman’s troopers failed to destroy a single one of that railroad’s major bridges, three of which lay immediately to the north of Hanover Junction. Cautious, unimaginative, lacking in initiative, and incapable of following clear, unambiguous instructions, Stoneman failed to live up even to Hooker’s minimal expectations. The cavalryman certainly fit within the Army of the Potomac’s profile of senior officers. Hooker accurately put it after the campaign: “No officer ever made a greater mistake in construing his orders, and no one ever accomplished less in so doing.”6

If Stoneman failed to distract Confederate attention, Sedgwick and Reynolds certainly managed their portion of the deception plan to a T. In the early morning hours of 28 April, Reynolds’s troops crossed the Rappahannock south of Fredericksburg after a massive artillery barrage; the movement gave every impression that this was where the main blow was coming. For three days the Confederate high command remained largely in the dark. Meanwhile, the XI and XII Corps crossed the Rapidan at Germanna Ford on the 29th while Meade’s V Corps moved cross country to cross the river at Ely’s Ford. At Germanna Ford, the Federals were helped by the fact that Lee had sent a small force of engineers to rebuild the bridge destroyed the year before—a sure indication of his plans to move north as soon as Longstreet and his two divisions returned to the Army of Northern Virginia. The Confederates were quickly chased away. As a bonus, Union engineers used the materials the Confederates had cut and prepared for their own bridge. Union forces now crossed into the Wilderness. That inhospitable area lay south of the Rapidan from west of Germanna Ford to the east of U.S. Ford. It was a flat, miserable landscape of tangled undergrowth, vines, scrub oaks, poison ivy, and few roads. In other words, it was an area where movement was difficult and communications among units almost impossible.

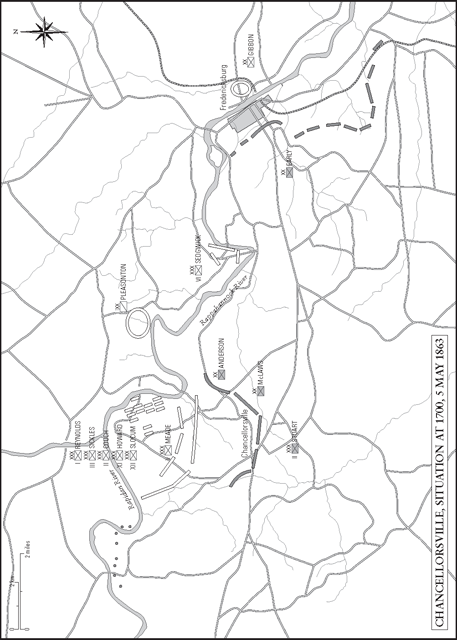

By 30 April the Union forces gathering on Lee’s left flank to the west represented a major threat. Meade, Howard, and Slocum had all reached the outskirts of Chancellorsville with their advanced units pushing down the Orange Turnpike and the Orange Plank Road toward the Confederate dispositions near Fredericksburg. Moreover, Couch’s II Corps had already crossed at U.S. Ford and was just north of Chancellorsville. At midafternoon, the lead corps commanders conferred. Given the lack of response by the Confederates, Meade proposed they continue the advance with all their forces. Slocum, however, was the senior officer present and demurred, his own caution reinforced by Hooker’s instruction that no advance beyond Chancellorsville occur until arrival of the II and V Corps. By nightfall on 1 May Hooker had nearly 80,000 troops on Lee’s western flank, while there were a further 40,000 troops pressing on Fredericksburg to the southeast with approximately 7,000 Union cavalry loose in the Army of Northern Virginia’s rear. To oppose that host, Lee had barely 56,000 soldiers. But war is always more than a matter of numbers.

While Slocum was living up to the Army of the Potomac’s culture of caution, the reaction in the Confederate high command underlined the difference in competence as well as culture between the two armies. By the 30th, Lee had sufficient intelligence to determine that Hooker’s main effort was on his left flank to the west and that the crossing south of Fredericksburg represented a feint. The response was swift and risky, but Lee knew his opponents. Jubal Early with his reinforced division of approximately 12,600 men remained as a holding force on Marye’s Heights overlooking Fredericksburg. Meanwhile, the rest of the army under Jackson and Lee moved directly against the the Union corps at Chancellorsville.

The fighting on 1 May underlined Lee’s swift response and Hooker’s tentativeness. Union forces had moved out in three columns to the east: Two of Meade’s divisions on the left flank up River Road, Sykes’s division of Meade’s corps up the Orange Turnpike, and Slocum’s XII up the Orange Plank Road on the right. Sykes moved quickly; Slocum, living up to his name, moved slowly, so that when the two corps ran into the buzz saw of Jackson’s advancing units, Sykes, with no support from XII Corps, was almost immediately in trouble. At that point, Hooker pulled his advance units back. It may well be that he feared an encounter battle. Unfortunately, the Union retreat ceded key ground to the east of what would become the front line between the armies. Ironically, having deceived Lee completely, Hooker abandoned that advantage and chose to fight in the Wilderness, thereby minimizing the Union superiority in numbers. The initiative had swung to the Confederates.

The major effort that most of the Army of the Potomac expended on constructing breastworks and abatis to protect their positions suggests the degree to which the war was changing. There would be no standing out in the open to receive Confederate attacks, as had occurred in the Peninsula and at Antietam. Experienced corps commanders, like Meade and Couch, were not about to take chances. By going over to the defensive around Chancellorsville, Hooker was daring Lee to attack him, which is what the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia had already decided to do. Still, Hooker also worried about his right flank, which was dangling with virtually the entire XI Corps facing south. He urged Howard on the night of 1 May to contract his line and swing it back so that a substantial portion of the XI Corps would face west rather the south—the precise direction from which Jackson’s devastating attack would come the next day.

But Howard demurred, missing entirely the purpose of Hooker’s suggestions. Such a move, he replied, would be bad for morale, and, anyway, he was strengthening his positions. Late in the morning on 2 May, Hooker was equally explicit in his instructions: “The disposition you have made of your corps has been with a view to a front attack by the enemy. If he should throw himself upon your flank, he wishes you to examine the ground and determine upon the position you will take in that event, in order that you may be prepared for him in whatever direction he advances. … The right of your line does not appear to be strong enough. … We have good reason to suppose that the enemy is moving to our right.”7

Howard paid not the slightest attention. Thus, due to sheer carelessness, the XI Corps commander put the entire army at risk. As Stephen Sears, the premier historian of the battle, has noted: “unimaginative, unenterprising, uninspiring, a stifling Christian soldier, Otis Howard was the wrong general in the wrong place with the wrong troops that day.”8 That said, there was a general unwillingness of too many senior officers throughout the XI Corps to believe there was a threat gathering on their flank to the west. Howard was not the sole cause of the disaster, simply a reflection of the Army of the Potomac’s culture. Furthermore, exacerbating the dangerous situation into which the army was falling was the fact that a communications snafu—Hooker’s communications with his widely dispersed forces would generally fail the general and the army throughout the battle—led the I Corps to begin its march from Fredericksburg to Chancellorsville three hours late, thus preventing Reynolds from being on the scene near the XI Corps when Jackson struck.

On the evening of 1 May, after driving the Yankees back to Chancellorsville, Jackson met with Lee. During the meeting, Lee indicated he had had no intention of pushing up the Orange Turnpike and the Orange Plank Road directly against the Army of the Potomac. Instead, he had already decided to move against Hooker’s right flank. Jackson delightedly acceded to his chief’s conception. By the end of their conference, the two had decided to take a major gamble—namely, to split the army into three parts: Jubal Early with his 12,400 men would remain on Marye’s Heights above Fredericksburg and pull back in a holding action, if pressed. Lee would hold in front of Hooker’s right flank with the 15,000 soldiers of McLaws’s and Anderson’s divisions, while Jackson took the bulk of the army, more than 26,000 soldiers, on a flanking march. To reach Hooker’s flank was going to take an all-day march, during which Lee’s small force would face overwhelming numbers. It was risky, but great victories are not won without risks.

Once Lee had determined the operational approach, the Confederates acted with a dispatch that stands in stark contrast to the patterns of their opponents. Jackson’s troops were ready at first light on the morning of the 2nd. Urged on by their officers, they began the long march to move around Hooker’s flank. Jackson moved up and down the column, spurring the troops with laconic encouragement: “press forward, press forward. … See that the column is kept closed and that there is no straggling … press on, press on.”9 For Lee, it was a time of uncertainty; he wrote Davis that he was moving on Hooker’s flank and that if that attack did not go well, he would pull back along one of the railroad lines, but would insure that his army remained between Hooker and Richmond. Jackson’s advance went largely unhindered except for a brief foray by Sickles.

The Confederate move to the west was in plain view of the III Corps, and its commander, Sickles, urged Hooker to allow his corps to attack Jackson’s flank. Hooker only relented when most of the Confederate column had already passed. There was some serious skirmishing, but it was already too late, and Jackson’s lead units were already approaching their deployment positions on Howard’s flank. While Sickles had seen the opportunity, he had failed to act on his own. The result of that failure partially explains his more aggressive actions on the second day at Gettysburg, where he would take the entire III Corps out of the line along Cemetery Ridge in direct contravention to his orders, because he thought the ground in front of him offered better defensive positions.

In the early afternoon Confederate cavalry found the end of Howard’s line, and Jackson, at the front as usual, found himself looking down the whole line of the XI Corps. At 1500 he dispatched a message to Lee that one of his divisions was up and the other two were following closely. Still, whatever Jackson’s efforts to speed things up, it took time to deploy divisions through the tangled mess of the Wilderness. Nevertheless, not all were caught by surprise; Carl Schurz, refugee from the 1848 Revolution in Germany and now a politician and volunteer general in America, had redeployed three regiments and made as many obstructions in his rear as he thought he could get away with, given Howard’s orders.

At 1730 Jackson asked General Rodes on his right wing whether his troops were ready; “Yes, sir!” came the reply. And so Jackson launched the devastating attack that came close to destroying the Army of the Potomac. The storm broke on an unprepared XI Corps; even Schurz’s three regiments could only delay the Confederates for a few moments as the tide swept eastward, not surprisingly led by Jackson himself, urging his soldiers “press on, press on.” Hooker was alerted to the disaster at 1830 when a broken mob of XI soldiers boiled down the road from the west to his headquarters. Howard’s corps broke so completely that nearly 80 percent made their escape, while half the casualties were prisoners; in other words, there was little time to fight, so complete was the surprise.

The distance Jackson’s troops had to cover, the confusion caused in advancing through the Wilderness, as well as resistance by small groups of Howard’s soldiers, allowed Hooker and his subordinates to patch together a line. Hooker ordered Reynolds’s corps, still on the other side of the Rapidan, to hurry forward as quickly as possible; Meade, on his own initiative, shifted his V Corps to cover the lines of communications to the river. As dusk approached, Jackson, with a small party, accompanied by A. P. Hill and his staff, rode forward to sort out the confusion and keep the drive going. It was a fateful decision; in the darkness, North Carolina infantry mistook the staff riders for enemy cavalry. A volley of musket fire then devastated both parties, killing or wounding a number of officers. Jackson went down with a severe wound in the arm, an injury further aggravated by being dropped by the soldiers carrying him to the rear. Amputation followed and the inadequate medical care of the time eventually led to his death from pneumonia. Hill was also wounded, which meant no one was available to take command until Stuart could arrive. Jackson’s wounding and the lack of a replacement to command the left wing halted the fighting, and quiet settled over the broken and bleeding soldiers.

While Hooker’s troubles on his right flank had exploded, he took some comfort in believing that if Sedgwick’s VI Corps moved with alacrity, it could drive the Confederates up the Orange Plank Road and catch Lee’s right flank in a vice. But Sedgwick displayed not the slightest willingness to move, even when Early pulled most of his division off Marye’s Heights and moved off to the northwest. Only a direct order forced Sedgwick to cross the Rappahannock. He then halted despite the fact that there was only a single Confederate brigade holding the heights. By the time he moved against Marye’s Heights, Early was back in position. Hooker would get little help from that quarter.

The fighting that occurred on Sunday 3 May proved among the worst killing days of the Civil War, ranking with Antietam and Fredericksburg. For ferocity of fighting, it may have been the worst day of the Civil War, for the battle was largely over by early afternoon, while the other two battles lasted all day. The day also marked Jeb Stuart’s greatest hour. As a result of the previous evening’s fighting, a dangerously thin salient poked out of Hooker’s lines, a salient largely held by Sickles’s III Corps to the west and Slocum’s XII Corps on the east with a portion of Couch’s II Corps at the eastern base. Here Hooker’s decision to remove Hunt as commander of the army’s artillery exacted a heavy price, because, while Union artillery was superior in every category, it fought in a disjointed fashion throughout the day without the centralized control that would have allowed Union guns to focus on the Confederate artillery. Moreover, even before the fighting started, Hooker abandoned the crucial high ground at the salient’s tip, called Hazel Grove. In Confederate hands, it allowed Lee’s gunners to enfilade Union positions.

Lee’s orders to Stuart were straightforward: attack to your front and drive “those people” (Lee’s characterization of Federals) off the ground. Stuart launched his attack with his forces echeloned to hit the west side of the salient. Almost immediately Union gunners at the center of the salient were in trouble from converging fire. Had Hunt been in command, given his expertise and ability to concentrate artillery, he would have dueled with the Confederate batteries and eventually silenced them. But he was not on the scene, and local Union battery commanders, responding to individual brigade, division, and corps commanders, focused on the infantry battle. What is most remarkable about the fighting is that Hooker fought the battle with the three corps in the salient, while Meade’s V Corps, backed by Reynolds’s I Corps, was immediately available to the north. The Federals successfully halted and then drove back the initial Confederate attack. Nevertheless, the salient slowly constricted as Stuart threw everything he had into breaking the Union lines. The casualties were frightful. Typical of Confederate losses was the fate of Brigadier General Stephen Ramseur’s brigade, which lost 788 out of 1,509 soldiers.

In the midst of the fighting, a Confederate cannon ball hit a post on the porch of the Chancellor house against which Hooker was leaning. Concussed and badly bruised from his fall off the porch, Hooker was knocked out for nearly half an hour and for the remainder of the battle failed to recover his equilibrium. For a short period, Darius Couch, as senior officer, assumed command, but felt constrained by what he regarded as Hooker’s intentions. Shortly thereafter Meade arrived at the army’s headquarters to urge that his fresh corps attack Stuart’s flank. Here Lincoln’s words, urging Hooker and Couch, to “put in all of your men,” still haunts the historian. In every sense Meade was in a position to do to Stuart what Jackson had done to Howard the day before. Had Hooker accepted Meade’s proposal, Stuart and the whole Confederate position on Lee’s left flank would have been in desperate straits. If he had then thrown in Reynolds’s corps, history might well have recorded Hooker’s victory at Chancellorsville. In Hooker’s concussed situation, he turned the Pennsylvanian down. Instead, he ordered Couch to pull the three corps out of the salient, while under heavy fire. In desperate straits the Union troops accomplished that difficult maneuver. The Army of the Potomac now retreated into a well-protected and fortified position, hoping that Sedgwick had achieved something. The casualties suggest the ferocity of the morning’s fight: Confederates 8,962 killed, wounded, or missing; Union 8,623—over 17,500 casualties in a little over six hours of fighting.

While this murderous fighting was going on over the morning of the 3rd, Sedgwick’s VI Corps prepared with exquisite slowness to storm Marye’s Heights. With Early back on the heights, it appeared as if Union troops were again to suffer heavy casualties on the killing ground of December’s slaughter. In fact, Union casualties would prove heavy, but not nearly as heavy as they might have been had Early deployed his troops effectively. As Union troops took the heights, Early pulled back, while Sedgwick leisurely advanced toward Lee’s rear. In another of those incidents that typified the incapacity of Army of the Potomac commanders to display initiative, Brigadier General John Gibbon, with a detached division of the I Corps and not under Sedgwick’s command, followed his orders and occupied Fredericksburg and its bridges, while the VI Corps meandered off to the northwest. Neither commander provided troops to garrison Marye’s Heights, which the Confederate promptly reoccupied.

For Lee the next two days were frustrating. For once his subordinate commanders failed to move with dispatch, a reflection perhaps of the stress they and their troops had been under over the previous two days. On the 4th, with Hooker driven back into a bend in the Rapidan, Lee moved against Sedgwick to destroy the VI Corps. The result was some sharp fighting, but for once the Confederates failed to “put in all of your men.” By the end of the day Sedgwick’s troops had given the Confederates a bloody nose; to Lee’s immense frustration, Sedgwick, having pulled his corps back into a hedgehog position with the Rappahannock to its rear, retreated across Bank’s Ford to the north side of the river and out of danger.

Frustrated in his attempt to destroy Sedgwick, Lee turned back against Hooker and the Army of the Potomac. At this point one is struck by the similarities between Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, especially when one considers what might have happened on 5 May. On the night of 4/5 May, Hooker conferred with his corps commanders. By a vote of three to two they had elected to remain on the south side of the Rappahannock and Rapidan and fight it out with the Confederates. But Hooker had made up his mind in spite of the vote and the fact that his army held a strongly fortified position with its artillery skillfully deployed now that Hunt was back in charge. In fact, the ground held by the Union troops on 4/5 May still displays the outline of the major earthworks after more than 150 years. Nevertheless, Hooker ordered preparations to withdraw across the Rapidan and Rappahannock on the next night. The Union commander had lost the battle in his mind.

While Hooker’s corps commanders were preparing to withdraw, Lee was hurrying his troops back to launch a major attack. To Lee’s fury, nothing seemed to work quite right. To add to his difficulties a major spring storm pelted the armies. In the end the Confederates had to postpone the attack until the morning of 6 May, by which time Hooker had slipped back across the Rapidan and then the Rappahannock. Thus, on the morning of 6 May Lee found no one to attack. Had Hooker not retreated but remained in his defensive position, with two of his best corps (Reynolds and Meade) untouched by the fighting thus far, Lee might well have suffered an even more disastrous defeat than Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg. Certainly that was how Porter Alexander felt in his memoirs written after the war.

Who won Chancellorsville? The obvious answer is Lee and the Confederates. Certainly, in considering the slashing attacks he, Jackson, and Stuart had launched against a superior enemy, who had in the first hours of the battle caught them completely by surprise, their performance stands as one of the great pieces of generalship of the Civil War. Yet, the casualty figures on the two sides were nearly equal: a bill the Union with its superior population could afford to pay, but which the Confederacy in the long term could not. Moreover, throughout the battle, Lee had taken chances that had placed his army on the brink of defeat. Perhaps the battle’s most significant result was that Lee gained the impression his troops could achieve anything against impossible odds, an estimation that had a disastrous impact on his conduct of the battle the next July at Gettysburg.

The question, as quiet returned to central Virginia, was what alternatives were open to the Army of Northern Virginia, soon to be augmented by Longstreet’s return. It was in these days that the Confederate government and its most successful general laid out the future course of the war in both the East and the West. By so doing they ended whatever chances still remained for the Confederacy to win its independence, assuming of course that competent Federal generalship would finally appear in Virginia. Shortly after Chancellorsville, Longstreet, passing through Richmond to rejoin Lee, had an extensive conversation with James Seddon, the Confederacy’s secretary of war. While the situation in the West had yet to collapse, Lee’s chief lieutenant urged that in view of Chancellorsville the Confederate high command transfer his two divisions along with other reinforcements to restore the strategic situation in Tennessee.

Both Davis and Seddon were sympathetic to Longstreet, and on 16 May they met with Lee. Unbeknownst to the participants, at the time they were meeting, Grant’s army was thrashing Pemberton at the Battle of Champion Hill in Mississippi. Perhaps only Lee himself might have saved the Confederacy from the looming disaster, but whatever the fears of his superiors about the strategic situation in the West, Lee had no interest in that theater. The Confederate president asked: Should the Army of Northern Virginia reinforce the West? Lee would have none of it. As he later put it, “I considered the problem in every possible phase, and to my mind, it resolved itself into a choice of one of two things: either to retire to Richmond and stand a siege, which must ultimately have ended in surrender, or to invade Pennsylvania.”10 Thus, Lee argued that the Army of Northern Virginia should invade Pennsylvania to win a battle that would crush Northern morale. Underlying Lee’s conception were two dangerous assumptions: first, that Hooker could not concentrate his forces quickly enough against the invasion because of the need to protect Washington; and second, that the Union’s soldiers were substantially inferior to those of the Confederacy. Two meetings of the Confederate cabinet then confirmed Lee’s strategic analysis. So it was to be an invasion of the North in search of that elusive “decisive” victory.

Before the invasion began, Lee carried out a substantial reorganization of the Army of Northern Virginia, as a result of Jackson’s death. Longstreet would lead the I Corps with his divisions commanded by Lafayette McLaws, George Pickett, and John Bell Hood; Richard Ewell would lead the II Corps with Jubal Early, Edward “Allegheny” Johnson, and Robert Rodes as division commanders; and A. P. Hill would lead the III Corps with Richard Anderson, Henry Heth, and Dorsey Pender as division commanders. Astonishingly, considering the defeat, Hooker made fewer changes in the Army of the Potomac. Couch asked to be relieved of command of his corps, given what he considered the general failure of Hooker’s leadership. There was no alternative but to fire Stoneman after his appallingly bad leadership, but his replacement was Alfred Pleasonton, an officer of no particular attainment. John Buford, who would win fame at Gettysburg, would have been a superior choice, but Pleasonton had date of rank and in the Army of the Potomac that trumped competence. Astonishingly, Hooker did not fire Howard, who bore so much of the blame for the disaster on the army’s right flank; the Army of the Potomac would pay a price for that decision at Gettysburg. Hancock now assumed command of Couch’s II Corps, while Sykes replaced Meade in command of the V Corps, when Meade moved up to command of the Army of the Potomac at the end of June.

As Lee gathered his forces for the march north, Union cavalry caught Stuart’s cavalry by surprise and initially drove them in disorder to the rear in a skirmish near Brandy Station; the Confederates quickly recovered and after a nasty fight pushed the Union cavalry back. In fact, the tally of Union losses was nearly double those of the Confederates (907 to 523), but the Richmond press was critical, including the Daily Examiner’s rebuke that Stuart’s “much puffed cavalry of the army of Northern Virginia has been twice, if not three times, surprised since the battles of December, and such repeated accidents can be regarded as nothing but the necessary consequences of negligence and bad management.”11 While the skirmish disturbed Lee not in the least, it did upset Stuart. He persuaded Lee to allow him to attempt a repeat of the raid that had taken him around McClellan’s forces the year before. His initial instructions were to shield the passes through the Blue Ridge Mountains to keep Union cavalry from spying out what was afoot on the western side of the mountains. Then, Lee allowed Stuart to undertake a raid behind the Army of the Potomac. But Lee was also explicit that Stuart was not to forego his primary mission to keep the Confederate high command informed of what Hooker was up to, as the main army moved north into Pennsylvania.

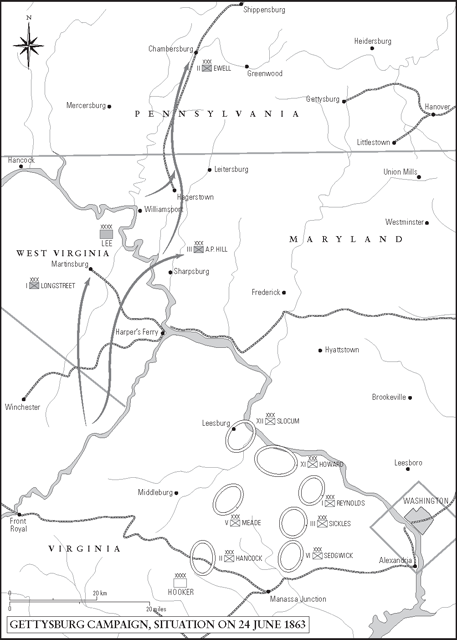

One-legged Ewell led the Confederate advance up the Shenandoah. Along the way, his corps scooped up Major General Robert Milroy’s division at Winchester in a repeat of Stonewall Jackson’s victory the year before. By 24 June Ewell’s corps had marched deep into Pennsylvania. From the start Confederate commanders made clear this was more than an expedition to seek a decisive battle. It aimed to feed the Army of Northern Virginia and gather in the riches of Pennsylvania to support the Confederate war machine. Hagerstown, Chambersburg, Shippensburg, Cashtown, and York, all felt the extortionist threats of the invaders. Besides being a looting expedition, the invasion would also involve the rounding up of blacks to be driven south and sold into slavery in Richmond’s slave exchange. In Chambersburg a woman solemnly recorded in her diary, “O! How it grated on our hearts to have to sit quietly & look at such brutal deeds … they [the local African Americans] were driven by just like we would drive cattle.”12 But while the Confederates ate off the fat of southern Pennsylvania, Lee remained blind; his best guess was that the Army of the Potomac was far behind, struggling to reach Maryland.

He was wrong. In fact, after initial fumbling and talk of moving south against Richmond in response to the Confederate invasion, Hooker had quickly moved his army between Lee and Washington, while at the same time preparing to engage the Army of Northern Virginia in Pennsylvania or Maryland. Starting late, the Army of the Potomac marched rapidly for once in its history as if the war’s outcome depended on it. In stifling heat and dust it beat a rapid trail through Virginia to Maryland and on toward Pennsylvania. But Hooker’s days as commander of the Army of the Potomac were numbered. Not only had Lincoln lost confidence in the general, but Halleck, as usual placing his personal interests and dislikes above the nation’s needs, was undermining Hooker’s ability to respond to the invasion. The quarrel between the generals boiled over with Halleck’s refusal to release troops from Washington’s defense to reinforce the Army of the Potomac as it swung north into Maryland. Moreover, he also refused to put the 10,000 troops guarding Harper’s Ferry under Hooker, but left them in as exposed a position as had occurred in September 1862.

The upshot was that Hooker sent his resignation to Halleck, who delightedly sent it on to the president. In the midst of the crisis, Lincoln had enough of quarreling generals, accepted the resignation, and promoted Meade to command the army. Meade was one of its competent and aggressive corps commanders, and so he, once described by one of his soldiers as “a damned old goggle-eye snapping turtle,” assumed command of the Army of the Potomac on 28 June.13 His task: to thwart Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania before it inflicted substantial political damage on the Union’s cause.

Without Stuart and his cavalry, Lee remained in the dark as to the approach of Union forces until the night of 28/29 June, when a spy, sent out by Longstreet two weeks earlier, returned with the news that not only were two corps of the Army of the Potomac at Frederick, but also others were poised to cross South Mountain, which would put Union troops astride Lee’s line of retreat. While Hill and Longstreet were in the immediate area, Ewell’s corps was thirty miles away, threatening Harrisburg, and Early’s division was all the way over at York, harassing its staid burgers. Lee immediately dispatched hurried orders for Ewell to pull back and concentrate with the rest of the army, preferably at Cashtown. Lee also warned his subordinate commanders that he did not want them to bring on a major engagement until he was sure of the situation.

Thus, the armies groped toward Gettysburg, where no less than ten roads converged from all points of the compass. Meade had determined to defend what appeared to be an ideal position at Pipe Creek, where his engineers began laying out proposed positions. But he also threw out a cavalry screen and sent Reynolds, his fellow Pennsylvanian, trundling up the roads leading toward Gettysburg with the I Corps, reinforced by Howard’s XI, and Sickles’s III Corps. By 30 June Union cavalry, under the tough, Indian fighter John Buford, had reached Gettysburg, ready to fight a holding action, should Reynolds deem it necessary. One of Buford’s brigade commanders commented that his men could hold the rebels for twenty-four hours. Ever realistic, Buford acidly replied: “No you won’t; they will attack you in the morning, and will come booming—skirmishers three deep. You will have to fight like the devil to hold your own until supports arrive. The enemy must know the importance of this position, and will strain every nerve to secure it; and if we are able to hold it, we will do well.”14

Late on the afternoon of 30 June, Heth sent one of his brigade commanders, Johnston Pettigrew, down the road to Gettysburg from Chambersburg to seize a store of shoes that Early had overlooked on his way to York. West of the town, the advance column ran into a screen of Buford’s cavalrymen. Mindful of Lee’s stricture not to bring on a general engagement, Pettigrew withdrew, only to meet with derision from Hill and Heth for supposedly mistaking Pennsylvania militia for Union cavalry. The following morning, Heth marched his division in column, confident he would not have to deploy into combat formation to brush the militia away. Instead he ran into Union cavalrymen putting down fearsome fire.

Heth had to deploy his division into combat formation, and while he did so, John Reynolds arrived to meet Buford at the Lutheran Seminary on Seminary Ridge. After a short conversation, the I Corps commander made a series of fateful decisions based on the fact that, like Buford, he believed Gettysburg offered excellent terrain to fight the Confederates. Messengers went out to Sickles and Howard with orders to move as rapidly as possible to support the I Corps; another went posthaste to Meade to inform him that Reynolds had recommended a stand well north of Pipe Creek. Most probably Buford and Reynolds agreed on a holding action on McPherson Ridge with their troops eventually falling back to the more defensible positions on Seminary Ridge, which had the additional advantage of requiring fewer troops to defend.

At the crucial moment when Heth’s superior numbers were beginning to overwhelm Buford’s cavalrymen, the lead elements of the I Corps arrived. As Reynolds moved forward to guide the deployment of two brigades of James Wadsworth’s division into line to bolster Buford’s troopers, a Confederate sharpshooter hit the general in the back of the head. General Abner Doubleday, who, as a captain at Fort Sumter, had fired the first Union reply to the Confederate bombardment in April 1861, assumed temporary command of I Corps. The arrival of Union infantry in substantial numbers turned what had been a large skirmish into a full-scale battle. Heth’s right-hand brigade ran into the Iron Brigade of Westerners, the 1st Brigade of the 1st Division of the I Corps, and received a thorough trouncing that included the capture of its commander, James Archer. Heth’s other brigade under Jefferson Davis’s nephew enjoyed greater initial success because it was farther removed from arriving I Corps infantry. But its attack soon collapsed, when a portion of the advancing Confederates moved into the unfinished railroad cut to the west of town and found themselves looking up at the barrels of Union soldiers, who could have been shooting fish in a barrel so superior was their position. Many surrendered, a few escaped. The survivors fell back, and Davis found himself with barely half the effectives with whom he had started the battle. The initial fighting had nearly wrecked Heth’s division.

Doubleday hustled up the other two divisions of the I Corps, and for the moment the Union position appeared secure. Shortly afterward, however, Howard arrived with his XI Corps. As the senior officer present, he assumed command and ordered his corps to deploy to the right of the I Corps, which swung the Union position north to guard the approaches to Gettysburg from that direction. It was noon as the XI Corps’s lead division moved into position. Howard also detached one of his divisions to hold Cemetery Ridge on the south side of the town. Nevertheless, while he was supposedly in command, he exercised that duty only in a negative fashion. While Doubleday commanded I Corps with competence throughout the afternoon, he received little support from Howard. Moreover, when Doubleday suggested that his I Corps pull back from McPherson’s Ridge to the more defensible Seminary Ridge, Howard turned him down cold. Eventually the I Corps did manage to pull back to Seminary Ridge, but under great pressure and only when it was too late. After the battle, Howard would blame much of the day’s failure on Doubleday, when in fact the Union collapse was largely Howard’s fault.

Nothing better underlines the differences in the command culture of the opposing armies than the actions of two corps commanders on the opposing sides and their impact—or lack of impact—on the course of the battle. The lead units of Slocum’s XII Corps began arriving at Two Taverns along with their general at noon. Two Taverns was five miles from Gettysburg. Almost immediately, officers and men heard the heavy rumble of cannon and musket firing indicating a major battle was occurring near Gettysburg. Queried by his staff as to whether the corps should not march to the sound of guns as well as the clouds of smoke on the western horizon, Slocum replied in the negative: his orders required him to go to Two Taverns and indicated nothing else. A messenger from Howard moved him not at all, nor did further reports of the fighting. Charles Howard, the general’s brother and staff officer, dispatched to seek Slocum’s aid at 1600, as the Union position at Gettysburg was falling apart, reported that the general “in fact refused to come up in person saying he would not assume responsibility of that day’s fighting and of the two corps.”15 The explanation for his refusal most probably lies in Slocum’s recognition, since the message came from Howard, that Reynolds was down and that, were he to arrive at Gettysburg, he would be the senior officer and responsible for conducting the battle until Meade arrived. Not until late afternoon did Slocum finally order his lead division to march to Gettysburg, while he himself did not arrive until the evening hours. As Howard’s brother put the matter: “Slow Come, he would not assume the responsibility of that day’s fighting & of the two corps.”16

In direct contravention of Slocum’s lack of initiative, Ewell and his division commanders, moving from York and south of Harrisburg to concentrate with the remainder of Lee’s army near Cashtown, heard the firing from Gettysburg and immediately marched to the sound of guns. The first of Ewell’s divisions to arrive was that of Major General Robert Rodes, new to command. Without executing a proper reconnaissance, Rodes launched his brigades independently in an attack from Oak Hill down the Mummasburg Road into what he thought was an open Union flank. In fact, there was a relatively strong Union position along a stone wall directly to his front. Edward O’Neal’s brigade on the Confederate left was routed first, while the second, Alfred Iverson’s, consisting almost entirely of North Carolinians, was caught while moving past Union troops on their flank. They were slaughtered. One bittersweet story to come out of the battle was that of “Sallie,” a bull terrier, and mascot of the 11th Pennsylvania on the I Corps flank, who, when separated from the retreating troops in the afternoon’s collapse, returned to the scene and guarded the regiment’s dead and wounded until the Confederates withdrew. She was killed by a stray bullet in February 1865 at Hatcher’s Run.

At 1430, Lee finally arrived; but this was largely a soldiers’ battle, and control of its course remained in the hands of his subordinates. By this point, the arrival of the rest of Ewell’s corps spelled the doom of the Union position. Heavily outnumbered, badly deployed with Francis Barlow’s division well to the front of the remainder of the corps and with the Howard nowhere to be seen, the XI Corps gave a repeat of its Chancellorsville performance. Early’s division smashed into the XI Corps front and soon enveloped its right flank. After some initial attempts to stand, it broke and ran. Its largely German contingent had been known for its slogan of “we fights mit Siegel (its first commander).” Wags in the Army of the Potomac now quipped, “We runs mit Howard.” As the XI Corps fell apart, its troops were soon joined by the veterans of the I Corps, who were now under great pressure on their right by a portion of Rodes’s division and from their front by Pender and what was left of Heth’s division. Exacerbating the disaster was the fact that the number of roads running through Gettysburg created considerable confusion for Union troops desperately attempting to reach Cemetery Ridge.

For Lee, the opportunity to finish the destruction of the two routed Union corps beckoned. But Hill’s corps was in bad shape: the fighting thus far had wrecked Heth’s division, while it had mauled Pender’s. Ewell’s corps was in better shape, but deployed directly to the front of Union positions on Cemetery Ridge, which the division that Howard had detached had already turned into a formidable defensive position. Lee’s instructions were anything but clear and left considerable latitude to Ewell. He was “to carry the hill occupied by the enemy, if he found it practicable, but to avoid a general engagement until the arrival of the other divisions of the army [i.e., Longstreet], which were ordered to hasten forward.”17 But one of Ewell’s divisions was still well to the rear, and he hesitated to attack. Longstreet, who had just arrived, urged an immediate attack, as Union reinforcements were arriving in strength. But Lee refused to order an attack until Ewell was ready.

Longstreet and Lee held a long conversation after Longstreet’s arrival. For Longstreet the whole purpose of the campaign had been to seek an excellent defensive position in a strategic location that would force the Army of the Potomac to attack. When he broached the issue, Lee was as usual decisive: “No, the enemy is there and I am going to attack him there.” Longstreet was nothing if not persistent. He suggested that the Union troops were there because they wanted the Confederates to attack. Lee was not persuaded: “They are there in position, and I am going to whip them.”18 At that point, Longstreet, seeing Lee’s blood was up, rode west to move his divisions along the road from Cashtown.

Meanwhile, Union commanders were also deciding on their strategy. When news arrived at Meade’s headquarters in early afternoon that Reynolds was down—from a New York Times reporter—the new commander of the Army of the Potomac ordered Hancock to turn over command of the II Corps to one of his division commanders and ride hard for Gettysburg to replace Reynolds as commander of the army’s lead units. Immediately on arrival, Hancock found his authority disputed by Howard, who cited his seniority. Hancock, who possessed great bravery as well as common sense, refused to indulge in an unseemly argument, given the circumstances. He simply remarked, “I think this the strongest position by nature upon which to fight a battle that I ever saw, and if it meets your approbation I will select this as the battle-field.”19 The line Hancock laid out extended in a V shape based on Culp’s Hill and the northern portion of Cemetery Ridge. The fishhook would emerge on the next day as the Union troops filled in the gap and extended the line down Cemetery Ridge to Little Round Top. Howard agreed, and that settled matters, at least as far as the Union was concerned. His mission complete, Hancock returned to Meade.

The fighting was now over as evening descended, seemingly a Confederate victory. Nevertheless, the casualty figures suggest the level of fighting as well as the reality that it was a Pyrrhic victory: approximately 9,000 Union casualties (well over a third of them prisoners), and 8,000 Confederates. Over the course of the evening, Union forces flooded in. Sickles and his III Corps began arriving at 1800. Slocum’s XII finally began arriving later that evening. As the senior officer in terms of date of rank, he commanded the forces gathering at Gettysburg until Meade arrived after midnight. After a brief survey of the line, the new commander of the Army of the Potomac confirmed Hancock’s decision to stand on the fishhook. By late morning only the VI Corps had yet to come up, but Sedgwick was on the march. At least when he received a direct order, Sedgwick could move with dispatch. Those morning hours provided Meade’s troops with the time they needed to prepare their defenses.

In parts of the Union line more substantial work was afoot than in others. What one sees at Gettysburg, as at Chancellorsville, was a transition from the open order of simply awaiting an enemy attack that characterized the fighting in 1862 to the rapid establishment of major defensive works at every opportunity that would occur in the 1864 campaigns. Nothing characterizes this transition more clearly than the work undertaken by Brigadier General George S. Greene’s brigade of New York volunteers. Nicknamed “old man Greene” by his soldiers, he was sixty-two and a West Point graduate and had left the army to work as a civil engineer on major projects such as the Central Park reservoir. On the outbreak of the war he had volunteered his service. As we have seen, he had performed in outstanding fashion at Antietam. Now on Culp’s Hill, Greene drove his soldiers over the night and morning hours of 1/2 July to dig trenches and build rock embankments as well as a traverse to cover his flank despite the taunts of his division commander, Major General John Geary and, not surprisingly, his corps commander Slocum.

On the Confederate side, Lee had already resolved the question of whether to attempt to maneuver around Meade or stay and fight it out at Gettysburg. In the morning Longstreet again attempted to persuade Lee to change his mind, but to no avail. Lee’s initial conception for the second day was a two-pronged attack: Ewell would strike the Union positions at the apex of the fishhook, while the main blow would hit the Army of the Potomac’s southern flank. However, in the early morning hours, the conception unraveled. Ewell disliked the looks of Union defenses on his front, defenses strengthened and reinforced during the night. He suggested to Lee that the proper approach would be an envelopment of the southern end of the Union line. However, it was clear that to move Ewell’s corps across the Union front would only suggest what was coming. In the center, Hill’s corps, immediately to the west of Ewell, had been badly shot up the day before and was incapable of executing a major attack.

Thus, it would have to be Longstreet, but Evander Law’s brigade was still far back on the road from Cashtown and had to make an exceedingly long march to reach the far right flank of what would be a massive assault on the southern end of the Union fishhook. Lee then decided that Ewell would make a supporting attack on the Union forces on Culp’s Hill, as soon as he heard Longstreet’s attack go in, to prevent Meade from shifting troops to meet Longstreet’s blow. Almost immediately the frictions of war intervened. Early in the morning Lee sent out one of his staff engineers, a certain Captain S. R. Johnston, to scout the way for the deployment of Longstreet’s corps and determine how far south the Union defenses extended. It is difficult to reconstruct what Johnston did during his reconnaissance, because under close questioning by Lee on the captain’s return, he reported there were no Federal troops on the southern portion of Cemetery Ridge, nor were there any Union troops on either Little Round Top or Big Round Top. In fact, the whole area was swarming with Union infantry and artillery except on the Round Tops, but there were obviously Union signalers on the smaller hill. On that false intelligence, Lee ordered Longstreet’s corps to drive up the Emmitsburg Road and roll up the Union flank. Johnston’s after-the-fact excuse, as recorded by R. Lindsay Walker, for his lackadaisical reconnaissance was more typical of the Army of the Potomac than his own army: “he ‘had no idea that I (he) [Johnston] had the confidence of the great Lee to such an extent that he would entrust me with the conduct of an army corps moving within two miles of the enemy’s line.”20

Needless to say, Longstreet was not happy with Lee’s decision, while Longstreet’s failure to begin his deployment for two hours made Lee even unhappier. Lee did agree to allow a further delay to allow the arrival of Law’s brigade, which completed its twenty-four-mile march in nine hours and finally arrived at noon. Confederate troubles were, however, not over; the initial route plotted out by Captain Johnston would have taken the troops onto ground visible to Union troops, so the whole column had to backtrack, nearly doubling the distance that Hood’s division had to cover. Longstreet’s troops would not be in position to launch their attack until late afternoon, well past the time Lee had wished.

On the Union side, Sickles decided the III Corps’ position along the Union line running south from Cemetery Hill was not nearly as defensible as it would be if he moved his troops out approximately half a mile to the Peach Orchard on his front and swung it back to a rocky outcropping below Little Round Top. Sickles attempted to get permission from Meade for such a move, who sent the artillery master Hunt to check the ground. Hunt pointed out to Sickles that the move, while it might have some advantages, would spread the III Corps too thinly and thus make its task more difficult. Nevertheless, with no definitive orders from Meade, Sickles took matters into his own hands, as he had not done at Chancellorsville, and ordered his corps to advance. Watching them move out, Hancock sardonically remarked: “Wait a moment, you will soon see them tumbling back.”21

As the Confederates massed on the Union left, Hood, the southernmost division commander, urged Longstreet to allow him to move deeper into the Union rear. Longstreet replied that Lee’s orders were orders, and Hood was to advance as instructed. At 1600 Hood’s division advanced; McLaws’s would follow at 1700 and Anderson’s at 1800. Ewell would not begin his attack on Culp’s Hill with Johnson’s division until 1900, while Early would finish off the day with an attack on Howard’s XI Corps on Cemetery Ridge. The one advantage that Sickles’s advance possessed was that it broke up the coherence of the Confederate attack on the southern portion of the Union line. The artillery battery located on the top of Devil’s Den immediately began firing as Hood’s troops swept into the open. The ground over which that advance took place has recently been cleared by the National Park Service, and the distance to that point makes clear that it was indeed a lucky shot that hit Hood in the arm and took him off the battlefield. But then as Clausewitz notes, no other human activity is as much subject to vagaries of chance. Hood’s wounding threw his division’s attack into considerable confusion.

Because of the weakness of the command and control system in Civil War armies, Hood’s successor, Law, provided no clear guidance to the division’s fight. Most of the division became involved in the fierce fight around Devil’s Den, while William Oates and the 15th Alabama clambered up Big Round Top, which was covered entirely with trees. They then moved down into the valley between the two hills only to be greeted by a furious volley as they attempted to move up and seize Little Round Top. Those Federal troops arrived providentially due to the individual initiative of a relatively junior officer. The army’s chief engineer, Gouverneur K. Warren, had recognized the vulnerability of the Union position, should the Confederates gain possession of Little Round Top. Galloping to find troops to hold that position, he had run across Colonel Strong Vincent’s brigade of Sykes’s V Corps moving to bolster the III Corps. Vincent responded by moving his brigade up Little Round Top to hold the hill’s left side. Warren continued on his search; he was able to spur two guns and Stephen Weed’s brigade of another division of the V Corps to move on the double quick to reinforce Union troops on Little Round Top. Whatever his later failings as a corps commander, Warren showed his considerable worth as a staff officer.

Arriving fifteen minutes before the Confederate attack boiled down Big Round Top and through Devil’s Den, Vincent’s brigade held long enough for Weed’s brigade, the lead regiment led by Colonel Patrick O’Rorke, to hold the right side of the position. On Vincent’s left, former Bowdoin College professor Joshua Chamberlain commanded the 20th Maine. Chamberlain is a particularly interesting case of what one might term a natural soldier; by this point in the war he had been in the army for less than eleven months and in command of the regiment for barely a month (appointed to command on 20 May 1863). In the desperate fight on the left flank of the Union line, the soldiers of the 20th Maine were about to run out of ammunition; at that point, Chamberlain ordered them to fix bayonets and charge. The Confederates, exhausted by their lengthy march and climb up Big Round Top in 82-degree weather, and the fierce fighting that followed their descent, broke and ran. Nevertheless, whatever the courage of Chamberlain’s men, it was only one action in the defense of Little Round Top that saw Vincent, Weed, and O’Rorke’ killed. But the line held, and the Confederates failed to envelop the fishhook.

At 1700 Longstreet launched McLaws’s division at the apex of Sickles’s salient. For the next hour the fighting wavered back and forth, as Meade rushed reinforcements to hold the exposed positions. Most of Sykes’s V Corps was drawn into the vicious fighting centering on the Peach Orchard (recently replanted by the National Park Service) and the wheat field. Sickles went down from a shell that took off most of his leg below the knee; the New York politician, eager as always to embellish his reputation, left the battlefield on a stretcher smoking a cigar so his men would know he was still breathing. After his leg was amputated, he kept the bones on his mantle in Brooklyn. By the time its line collapsed, the III Corps had suffered approximately 4,000 casualties, but with the help of reinforcements had ground Longstreet’s attack to a halt.

At 1800 Anderson’s division of Hill’s corps, temporarily assigned to Longstreet, although neither Hill, nor Longstreet, nor Anderson was sure exactly who controlled the division, went in. The ferocity of the Confederate attack, along with the fact that Meade had sent in most of his available troops as reinforcements to the desperate fight swirling around the III Corps, came close to rupturing the center of the Union line. Hancock, now in charge of the III Corps as well as his own, hurried one of his divisions and an additional brigade south from their emplacements on the northern side of the fishhook to reinforce the line. To his horror he saw a portion of Anderson’s division break out into the open. To buy time, Hancock sent the 1st Minnesota into the fray with a suicidal charge that halted the Confederate advance for a few minutes. It was enough. Reinforcements from the II Corps arrived in time to stop the Confederate drive. Ambrose Wright’s brigade of Anderson’s division had a brief glimpse of the Union rear before Union reinforcements overwhelmed it.

One more fierce fight took place as twilight descended on the broken, bloodied landscape. As was usual with Lee, his orders to Ewell left his subordinate with considerable latitude. When Longstreet’s attack went in, Ewell was to launch a powerful demonstration to keep Union forces on Cemetery Ridge and Culp’s Hill in place, while if there were prospects for success, he was to launch a full-scale attack. Ewell’s demonstration involved moving the artillery from Johnson’s division out into the open, where Union guns overwhelmed them. Nevertheless, with the time now approaching 1900 Ewell decided to launch Johnson’s division against Culp’s Hill. Unbeknownst to him, Slocum, having played a major role in the disaster the day before by not showing up, had decided to display initiative by removing his whole corps to reinforce the Union center, when Meade had asked for only one division. That decision almost lost Culp’s Hill. But Slocum did leave Greene’s brigade behind in the fortifications the corps commander had ridiculed in the morning. In fierce fighting, Greene’s single brigade on the right side of Culp’s Hill held its positions against much of Johnson’s full division, while Wadsworth’s division of the I Corps, badly battered the day before, held the left side. Ewell launched his final attack at 2000 with two brigades of Early’s division. The attack came close to driving Howard’s XI Corps, once again distinguishing itself for its lack of staying power, off Cemetery Hill, but it was already after dark, and Union reinforcements, flowing back to the northern part of the fishhook, restored the situation.

What had the second day at Gettysburg accomplished? In a tactical sense not much. Meade still held the fishhook; Lee still held the initiative. Once again Union cavalry had done little to screen Meade’s forces or alert him to the Confederate move to his left. Needless to say, Stuart’s absence—he would not arrive near the battlefield until 1800 that day—had led the Confederates into a number of faulty assumptions. In the end, the second day at Gettysburg had become a terrible encounter battle, where more often than not the troops ran into each other and even when on the defensive fought without cover. Only Anderson’s attack had come close to success. On the other side, the Union commanders had displayed considerable initiative; unfortunately, the initiative of Sickles and Slocum had come close to costing Meade the battle. However, at a lower level, the actions of Warren, Vincent, Weed, Chamberlain, Hancock, and Greene had remedied critical situations and turned the course of the battle.

Given the closeness of the fighting on 2 July, Meade was unsure whether he should stand or retreat to Pipe Creek. As Hooker had done at Chancellorsville, he convened a midnight meeting of senior generals. Unanimously they voted to stay, and unlike his predecessor, Meade accepted the result. As the meeting broke up, Meade turned to Gibbon, one of Hancock’s division commanders, who held a substantial portion of the center of the Union line, and commented: “If Lee attacks tomorrow, it will be in your front.” Gibbon confidently replied that he hoped the Confederates would and that “we would defeat [them].”22

With the failure of the second day’s attack, the choice confronting Lee was whether or not to continue the battle or withdraw, the latter choice an admission of defeat. By now the fighting had savaged every major unit in his army except for Pickett’s division. Not surprisingly Longstreet was in favor of maneuvering around Meade to move between the Army of the Potomac and Washington. But the allure of decisive victory, along with the belief that his soldiers could accomplish anything, led Lee to try one more throw of the iron dice. His plan involved three attempts to break the Union line. Johnson’s division of Ewell’s corps still held portions of the trenches on Culp’s Hill, and he was to launch his attack at the same time that the main attack went in. The main attack would come against the Union center with Pickett’s division. At the same time, Stuart, who had finally arrived, was to sweep around the Army of the Potomac and drive into its rear to create maximum confusion.

But none of the supporting attacks worked out. Even before dawn’s first light, Slocum’s corps, returned to its positions on Culp’s Hill, had opened up an artillery bombardment on Johnson’s position. For nearly five hours, fighting continued until the Confederates, at a huge disadvantage on the lower slopes of the hill, finally broke off the engagement and retreated. The cavalry fight went equally badly for the Confederates. Stuart’s ill-conceived raid had exhausted his troopers. However, he still possessed superiority in numbers, because Pleasonton, who had contributed nothing to providing Meade with information, had deployed a substantial portion of his command to tasks other than protecting the Union rear. However, a furious charge by Custer’s brigade, consisting entirely of Michigan regiments, brought Stuart’s attack to a halt, while Union carbines dominated the small arms fight. Pickett would receive no help from this quarter either.

In the morning the Confederates began massing their artillery facing the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. Having tried both Union flanks, Lee decided he would now smash the Union center. Pickett’s division of Virginians would step off on the right with Pettigrew’s (replacing Heth who had been wounded two days before) and Isaac Trimble’s (Trimble replacing Pender also wounded the day before) divisions of Hill’s corps on the left. While Pickett’s division was fresh, Hill’s selection of Pettigrew’s division, badly shot up on the first day, as well as Alfred Scales’s brigade, also in bad shape, made little sense. The 26th North Carolina, for example, had lost 624 of its 840 men on 1 July. The initial attacking force numbered approximately 13,000 troops with two brigades in support, some 1,600 additional soldiers. There were a further 3,350 soldiers of Anderson’s division available for support, should matters go well.

The concentration of the Confederate artillery took virtually all morning. Unbeknownst to Confederate artillerymen, they would fight under a substantial disadvantage. A fire that spring had damaged the manufacturing center in Richmond that made the fuses for the Army of Northern Virginia; the fuses Lee’s artillery now possessed had been manufactured in Charleston and were slower burning. Thus, most of the shrapnel shells fired on 3 July would sail over Union positions protecting Cemetery Ridge and explode harmlessly behind the lines. Moreover, once the Confederate infantry attack began, it would block much of their artillery support from participating in the fight for fear of hitting their own soldiers.