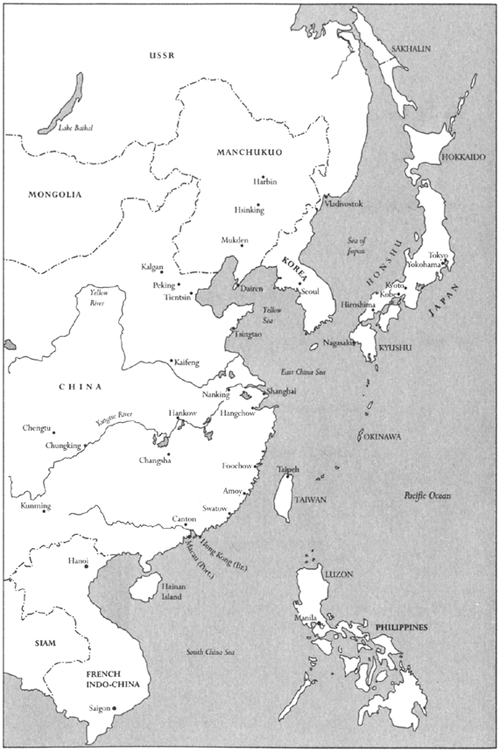

1. The Far East, 1941

Ilove this book as I do all my offspring but, like a wayward child, it landed me in some awkward pickles.

On the day of its first publication in 1998, it elicited a banner front-page headline in the Daily Express: ‘BETRAYAL: Revealed – How British firms and police aided Japan’s war effort.’ While I naturally welcomed the publicity, it provoked furious rebuttals. On the BBC Today programme I was confronted by an indignant British former prisoner of the Japanese. He vigorously defended the wartime conduct of British and other Allied citizens in the Far East. Arthur Titherington, chairman of the Japanese Labour Camps Survivors’ Association, told The Times: ‘The historian who has made these claims of collaboration was not there himself. He has no idea what it was like.’

Of course, by that criterion, neither Gibbon nor Macaulay (not to mention the greater part of all historians in the world who have ever raised their pens) could have written their masterworks. Nevertheless, my defence that I could confirm everything in my book on the basis of contemporary documentation cut no ice with Mr Titherington.

Shortly afterwards I was served a further lesson in the dangers inherent in over-reliance on archival evidence. A London solicitor acting for Hilaire du Berrier, an American citizen aged 90, resident in Monte Carlo, wrote to complain of libel in my report of his client’s wartime activities. Now I was confident that I stood on firm ground. Did I not have in my possession copies of files from the Shanghai Police Archives as well as United States intelligence records and other materials (including letters written by Mr du Berrier himself) that substantiated my incriminating allegations concerning him?

I assembled these papers in a large attaché case and, together with my supportive but worried publisher, met a libel lawyer of my own. At the outset I declared boldly that I would fight the matter, come what might. But as I started to open my case, the barrister informed me gently that all my documents would not be likely to impress a court. Where, he asked, were the witnesses who could corroborate the story I had spun from the written records? I told him that the inexorable passage of time had delivered almost every potential testifier to these events (save Mr du Berrier) to the court of final judgement. The lawyer shook his head sadly and explained that a judicial standard of proof was quite a different thing from mere scholarly accumulations of documents.

Perhaps, I surmised, du Berrier, who in his youth had been a notorious chancer, was only trying it on? Let us call his bluff! But his Monégasque domicile suggested the capacity to finance a lengthy suit. And his association, soon discovered, with the off-the-wall, right-wing John Birch Society betokened a fanatical determination to pursue causes to the bitter end. Quite apart from the danger of losing the case, my legal adviser warned me that the likely costs, if the case went to court, could easily drain my savings account – and then some. Only the timely demise of the plaintiff saved me from considerable expense and potential disaster. Happily one cannot libel the dead. My account of Mr du Berrier’s far from creditable career in China therefore remains more or less intact in this volume.

Tribulations of a different sort attended the Chinese edition of this book. Several publishers expressed interest in producing a translation and two actually signed contracts – only to withdraw from them later. The reason was a brief reference in the book’s conclusion to the massacre of students in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, in 1989. I insisted doggedly on publishing the book as a version intégrale. My would-be publishers explained that this would not be countenanced by the authorities in the People’s Republic. A projected Taiwan edition also fell by the wayside. Finally, after eighteen years of recalcitrance, I reluctantly gave way. After all, Western historians with infinitely greater claim to sinological expertise had in recent years consented to political bowdlerization of their works in Chinese translation. I therefore agreed that a Chinese edition might appear, shorn of the offending remark – with the proviso that it would be clearly stated in the front of the book that the text had been abbreviated. The publishers, my friends at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, faithfully acceded to that condition. A Chinese edition appeared a few months ago arousing, I am told, considerable interest.

As if all that were not trouble enough, I found myself, my book, and one of my historical characters, the half-crazy ‘Captain Pick’, drawn strangely into a fictional web. Alexander Hemon’s novel Nowhere Man, published in 2002, walked a tightrope between my world of historical fact and what Gary Shteingart’s rave review in the New York Times called a ‘flight of fancy … antic and ingenious.’ Sarajevo-born, Mr Hemon had emigrated to Chicago. A year or so later, when I myself took up residence in that city, I invited him over for drinks. While expressing appreciation for his interest in my work, I remonstrated with him about the liberties he had taken with my history, mingling imagination with reality. He would have none of it. The novelist, it appears, like the ex-serviceman, the lawyer, and the Chinese Communist, has his own way with evidence. We parted the best of friends but on completely different wavelengths.

So I tremble slightly at the prospect of this new edition. I have done my best to anticipate further problems. Indeed, on looking the text over, I decided that I had been a trifle (not more) too harsh in my depiction of du Berrier and excised one or two fruity adjectives. The events of 1989 have receded into more distant memory and are irrelevant to the subject of this book; I consequently followed the line of my Chinese edition and eliminated that unkind allusion. Meanwhile, over the years, several readers have helpfully pointed out errors of fact that I have taken this opportunity to correct. With these minor exceptions I stand by the account I gave in the first edition.

Amsterdam