CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

June 1940

Stan swung open the kitchen door and inhaled the delicious smell of one of his wife’s stews. So far rationing hadn’t stopped Flo producing tasty meals, and he wished above anything he could sit down and join his family at the table right now.

‘Sorry, love,’ he said as Flo turned to greet him. ‘This is a flying visit. I’ve got to cover someone’s shift tonight.’

Flo frowned. ‘But you worked last night. Surely they can’t expect you to go on patrol every night. That’s not right.’

Stan came across to her and put his hands on her shoulders. ‘I know, love, but it’s an emergency. I’m covering Billy’s shift.’

Mattie pushed open the back door and came in from the garden, overhearing her father’s remark. She stopped dead in her tracks, on the threshold between the back kitchen and kitchen proper. ‘Why? Whatever’s happened to Billy? Is something wrong?’

Stan looked at his daughter and gave a heartfelt sigh. ‘Have you heard the news on the wireless at all?’

Mattie shook her head. ‘We’ve just had the music on. Singing along helps the housework get done quicker.’

Stan nodded in understanding but he had to tell them what was going on. ‘I’m afraid it’s not good news from France. Hitler’s got our boys on the run, and they’re going to try to evacuate the whole army. That’s where Billy’s gone.’

Mattie turned and called into the back garden: ‘Kath, you’d better get in here and listen to this.’ She rested her hand protectively over her stomach, which was just beginning to show its new bump.

Kathleen ran in, wiping her hands on her cotton frock, followed by Gillian and Brian, both now much steadier on their feet. Their hands were covered in sand, as Stan had recently built a tiny sandpit for them. Kathleen made them wait in the back kitchen where she could clean them up at the sink.

‘What’s happened?’ she asked in a voice full of foreboding.

Stan repeated what he’d said and went on to explain that all available small ships and even little boats were crossing the Channel to join the rescue. ‘Billy knew some lads down the docks who could get hold of an old boat,’ he said steadily. ‘They thought it was their duty to go, even though they haven’t sailed beyond the mouth of the Thames for years. Billy says she’s seaworthy and they needed an extra hand, so I told him I’d cover his ARP shift. That young man is a hero, whether or not he’s actually in the armed services.’

Kathleen’s face went white. ‘Billy’s doing that? But he can’t swim. He never learned, he told me.’

Flo came across and put her arm around Kathleen’s shoulders, which had started to shake. ‘Don’t take on, Kathleen. He won’t need to swim. He’ll just have to do what the others tell him, pull on a rope or whatnot.’

Kathleen nodded slowly. ‘I hope so, I really do.’ Yet again it struck her that she’d overlooked Billy’s qualities too easily. He’d set off with no hesitation to save others and with no thought for his own safety. That was typical of him.

Mattie shut her eyes and swayed a little. ‘Oh God, I hope he finds Lennie. I do hope he finds him and brings him home. Don’t let Lennie be hurt. I couldn’t stand it. Not my Lennie.’

Flo let go of Kathleen and hugged her daughter. ‘Hush, Mattie. We don’t know Lennie’s there at all.’

‘Or Harry!’ Mattie cried, all her exasperation and irritation at her brother’s annoying ways forgotten at the prospect of his being injured, or worse. She looked at Stan and realised this was exactly what had been on his mind too. ‘He’s in France, we know he is.’

‘Sit down, my love.’ Flo quickly pulled a chair from the table and helped Mattie lower herself onto it. ‘We don’t know anything for sure. Worrying won’t help. We have to be strong, for the children. Chin up, my girl. Don’t let Gillian see you cry. We don’t want her upset as well.’

Mattie nodded dumbly.

‘I’ll make you a sandwich, Stan, to take with you, and you can have your stew at whatever time you get back,’ Flo said, while Kathleen busied herself tidying up the children, who hadn’t understood what was going on but had picked up on the atmosphere and realised the adults weren’t happy. Hastily she held each of them up to the sink and washed their grubby hands, singing a nursery rhyme under her breath to soothe them.

Stan took the cheese and pickle sandwich that Flo had hastily wrapped in greaseproof paper and tucked it into his inner pocket. ‘Thanks, love. Right, I’d best be off. I’ll bring back as much news as I can but don’t be surprised if we don’t hear anything for a while. Try not to give in to worry when we don’t know what’s really gone on.’

He quickly gave Flo a peck on the cheek and was gone.

Mattie stared at the door. ‘Now what do we do?’ she breathed.

Flo came and sat beside her. Her heart was leaden but she tried to inject as much hope into her voice as she could. ‘I’m afraid we wait.’

They waited like so many others in cities, towns and villages across the country. Everyone was desperately hoping that their loved ones had survived and were unhurt; nobody could say when they would know for sure. In Victory Walk, the nurses went about their business as usual, but many did so with heavy hearts. Edith was far from the only one to fear the worst while hoping for the best. She rode her bike to her regular roster of patients and managed to talk sensibly to a few new ones, yet largely with her mind elsewhere. She was relieved that she hadn’t had to break bad news to anyone; if the woman she had recently seen had been diagnosed with cancer and her difficult husband had caused problems, Edith doubted she would have been able to cope.

Fiona Dewar somehow knew what the matter was, in the way that she seemed to know most things about her charges’ personal lives, and kept an eye on Edith, making sure she wasn’t overburdened with new cases or required to do too many extra activities, unless she volunteered for them. Others could teach the first-aid course, for a start.

Alice watched over Edith like a hawk, keen to protect her as far as she could in this agonising period of not knowing. She also waited anxiously for news of Dermot and Mark; Dermot had written a few letters since he’d left London, just so that she knew they were both all right. She had no idea if their being doctors would have meant they were safer or not. What she did know was that neither of them was likely to run away from a fight.

She had no idea if Joe might have been caught up in the evacuation. His whereabouts were a mystery. There was no real reason why he would contact her, either, but she hoped for his sake and his family’s that he was safe, somewhere, wherever it might be. That image of him in the back kitchen at Christmas kept coming into her mind, and that sensation that he was there was something between them, something he wanted to say or do or was troubling him. She realised she very much wanted to find out what it might have been, all the while banishing the little voice that taunted her: ‘Maybe there won’t be a next time.’ She had to stay optimistic, for Edith’s sake.

Mary had immediately ceased her complaining about Charles when she understood what he had most likely been doing, frantically planning the army’s defence in France and the Low Countries. She also apologised to Edith for being thoughtless, thoroughly ashamed that she’d gone on and on about the captain’s unavailability when Harry and his comrades had been facing heaven knew what dangers. ‘He’ll be fine,’ she tried to assure her friend. ‘If any Germans come near him he’ll punch them on the nose and knock them out.’ Edith had tried to smile back, knowing the remark was well meant, but she doubted Harry would be able to get away so easily.

Gladys took to surreptitiously clearing up after Edith, going far beyond the boundaries of her job, because she didn’t want Edith to feel bad when she forgot to wash her mug or put away the cocoa. Gladys was fiercely fond of Edith, as one of the two nurses who had taken steps to help her when she’d finally admitted to being unable to read. Her loyalty to Edith and Alice was unshakable. Woe betide any of the others who made a thoughtless comment about Edith’s sudden absent-mindedness.

Even Gwen relented from her usual remorseless drive for perfection in all fields, not taking Edith to task when she put things away wrongly in the district room or hung up her cloak on somebody else’s peg. Edith didn’t notice but Alice did and was quietly amazed. Of course, if it had been a major mistake with a patient put at risk, that would have been a different matter. But Edith held herself together when on her rounds, and so Gwen for once cut her some slack.

Kathleen lifted Brian into his pram and set off to try to buy meat. She left early, as every kind was rationed now and she knew she faced the prospect of queuing at several different shops if she wanted to come home with the meagre portion her coupons allowed. First she tried for ham, but that had sold out. Then she went to another shop she’d registered at in the hope they would have bacon, but there was none of that either. The third shop, nearly all the way up to Stamford Hill, had just received a delivery of sausages, and had some fresh eggs too, so even though she’d had to walk further than usual she came back with enough for several meals, along with aching shoulders from pushing an increasingly heavy Brian.

‘You sit there,’ she said, propping him on her bed and making a little wall with her pillows to try to keep him still while she unloaded her shopping. ‘Here’s your rabbit – tell him about the morning you’ve had.’ She hummed to herself as she put the eggs on a high shelf, well away from curious little hands.

That done, she turned to the bucket of baby clothes she’d put to soak before leaving the house. The weather was warm and a gentle breeze was blowing – perfect for a bit of laundry. She could rinse them through, peg them out in the tiny back yard and then they might be ready to iron by teatime. Keeping up with Brian’s clothing was a ceaseless task – he never had much spare as he grew too fast, but she took pride in ensuring he was always clean, with a spare set of clothes always tucked into the bottom shelf of the pram in case of accidents. She had begun to put aside anything he’d grown out of that wasn’t worn too thin in case it came in useful for Mattie’s new baby. It was another chance to give something back to the generous Banhams.

She checked the collar of a little green shirt to see if it needed mending, and then carefully rinsed it out and set it in her washing basket. She was so engrossed in the task that she almost missed the knock on the door. Brian looked up from playing with his rabbit, his face expectant, as in his limited experience it was usually Mattie, and that meant Gillian as well.

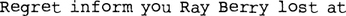

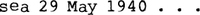

Mattie, however, usually let herself in immediately after knocking. Kathleen dried her hands on a threadbare towel by the sink and went to see who it was. Standing there was a boy of about fourteen in the uniform of the General Post Office, his bike propped precariously by her doorstep. ‘Mrs Berry?’ he asked. ‘Mrs Ray Berry?’

‘Yes,’ said Kathleen automatically, and on this fine sunny morning it didn’t occur to her what this might mean. Her first worry was whether she had enough loose change to tip the telegraph boy.

He pushed his flopping fringe out of his eyes and handed her a telegram. ‘This is for you, missus.’

Still it hadn’t dawned on her that these few moments would alter everything. ‘Thank you,’ she said, squinting a little at the dazzling sun which had just come out from behind a small high cloud. ‘Wait there, I’ve got some pennies indoors.’

The boy’s face grew concerned. ‘Think you should read it, missus.’

Kathleen smiled politely and popped back inside to her clay pot of coppers, which she kept on the top shelf and tried not to touch except for emergencies. ‘Here you are, for your trouble,’ she said, making no move to read the message.

‘Thank you, missus.’ The boy had no time to hang around and was off away down Jeeves Place to find his next port of call.

Kathleen shivered despite the warmth and stood in the doorway, her back against the jamb, suddenly extremely aware of all the sights and sounds around her – the familiar street, the open windows of her neighbours’ houses, the caw of birds, the squeal of the buses’ wheels from the High Street. The smell of dinner being cooked by the woman upstairs drifted down, a not very appetising chicken pie. Kathleen involuntarily wrinkled her nose, then took the plunge and read the telegram.

Slowly she read it again. The words seemed to be moving around and she couldn’t focus properly. Lost? Was that …? He couldn’t be. Ray was never lost for anything. But here it was in black and white. In a daze, she dragged herself over to the table and sank down, her hand shaking as it held the bit of paper.

Her head swam at the realisation that Ray was dead. Her husband, no matter what had passed between them. No more Ray. It wasn’t possible. Even when she’d hated what he’d done to her and how he’d treated Brian, even when he’d run off and not bothered to let her know where he was, she’d never imagined that she wouldn’t see him again. There was always the thought – half longed for, half dreaded – that he could turn up at any time.

Brian would be without a father now. She glanced across to where he’d half rolled off the bed but was still clutching his beloved rabbit, chattering quietly in nonsense language to it. If only Ray had appreciated his lovely son. Now he never would. She would have to raise him alone and somehow tell him about what sort of man his father had been, without letting her bitterness show. She sighed. She’d tackle that when the need arose. Thinking about it was beyond her right at this moment.

Kathleen went through the rest of the day on autopilot. She finished rinsing the clothes and hung them out in the tiny back yard to dry. She brought them in and ironed them. She made herself one slice of toast and poached one of the eggs to put on top of it, telling herself she still had to eat, and then forced it down although she had no appetite. Brian dozed off for his afternoon nap. She sat in the one comfy chair and watched the world go by in Jeeves Place. Mrs Coyne left with her shopping basket on her arm. After a while she came back again. Kathleen had no idea how much time had passed.

At last she lit the gas lamp and tucked her son firmly into his cot, gently easing away the toy rabbit he liked to clutch as he fell asleep. She didn’t want him trying to eat its ears – as she’d caught him doing last week – and choking. One day she would have to wash it, but then he would probably object as it would smell of Rinso laundry soap, and so she kept putting it off.

She watched the rise and fall of his chest as he breathed slowly, making little snuffling noises. She wondered if he would look like his father. That might be no bad thing; at least Ray had been handsome. Then again, if he hadn’t been so good-looking she might not have fallen for him and that would have been a blessing. On the other hand, she wouldn’t have had Brian. Nothing was ever simple. As long as he didn’t take after his father in terms of character … That would be up to her, to set him on the right path.

She jumped as there was a soft knock on the door. It wasn’t exactly late, but she was still wary as she approached the door, her stomach churning because of what had happened the last time anyone had come knocking. ‘Who’s there?’ she called.

‘Don’t worry, Kath,’ replied a familiar male voice. ‘It’s only me.’

‘Billy!’ she cried, flinging the door wide open. A rush of emotions assailed her, as she realised the shock of today’s news had made her forget that Billy was missing. ‘You’re safe. You made it back.’ Swiftly she drew him in, holding on to his arm. ‘Come on in, sit down, I’ll make us a cuppa,’ she went on, remembering her manners.

‘You don’t have to, only if you’re having one, Kath,’ he said, eyes bright at the sight of her. ‘Just thought I should pop round and show you I’m alive and in one piece. You don’t mind, do you?’

Kathleen tried to keep her voice steady but didn’t quite succeed. ‘Don’t be silly. We’ve been going out of our minds with worry. I’m just relieved to see you.’

He caught sight of her as the gas light shone fully on her face. ‘Here, Kath, hang on. What’s wrong?’

She turned her back to him, wringing her hands, almost unable to say the words. Once she spoke them out loud, there would be no going back. It would all be real. She took a deep breath. ‘Ray’s lost at sea.’

For a moment Billy couldn’t say anything. He took a step towards her. ‘Oh, Kath.’ He could tell she didn’t want him to come any closer. ‘Kath, are you all right?’

She wouldn’t meet his gaze but turned her face to the ceiling. ‘Yes. No. I don’t know. It’s too much to take in. Look, I’ll make that tea, it’ll help.’

‘No.’ He went as if to move towards the kitchen. ‘I’ll do it, I know where you keep it all …’

‘Stop, Billy. Really. I want to do it.’ There was comfort in small routines, she’d learnt that this afternoon. Swiftly she boiled the kettle again and set out an extra cup, putting fresh leaves into the pot rather than reusing the ones from earlier in the day as she would have done if she’d been alone. ‘But tell me about how you got back. At least you’re home in one piece, after we thought you might be a goner.’ She set the battered tray down on the table.

Billy shook his head. ‘No, takes more than a few pot shots from Jerry to get rid of me.’

Kathleen’s hand flew to her mouth. ‘What, did they shoot at you? Oh my God. Are you all right, are you hurt?’

He shook his head again and sat down on the hard wooden chair, as she perched on the edge of the armchair. ‘They shot at all the little boats. Trying to put holes in them so they’d sink, I suppose. Well, they never managed it. Our boat, the Molly May she was, she lasted all the way back to Limehouse. We didn’t know if she’d make it; she struggled a bit and she was low in the water as we packed her so tight, but she did us proud.’

Kathleen smiled despite herself. ‘You’re talking like a sailor, Billy.’

Billy wiped his hand over his face. ‘Nah, one thing I realised on that trip was what real sailors are like – how they can handle a boat, the tricky situations they can get themselves out of. I admired them, I don’t mind telling you. We just went where we was put.’

‘And did you rescue many soldiers, Billy? What was it like?’

Billy’s expression clouded over. ‘I don’t want to tell you the details, Kath, I don’t want the boy to overhear,’ he said. ‘It was like a nightmare. I don’t ever want to see anything like it ever again. Those poor men. Boys, some of them. Terrible, it was.’ He paused for a moment, remembering. Then his tone changed. ‘But we got lots of them off the beach there, thousands. You know what, it was a big success. Everyone is saying so. We took dozens and dozens back with us – crowded as anything, it was, but we got them home safe. A couple were hurt bad, but with my ARP training I knew what to do to staunch the blood from their wounds. Then they got took straight to hospital when we reached Blighty.’ He stopped to take a breath. ‘And then we turned around and went back and did it all over again.’

‘Oh, Billy.’ Kathleen’s face was full of concern.

‘You should have seen the Molly May,’ he continued. ‘She was a beauty. It was like she knew she was on a rescue mission, she darted in there quick as you like, for all she was an old girl.’

Kathleen steeled herself to ask the next question. ‘Don’t suppose you saw anything of Lennie? Or Harry? Or Pete?’

Billy shook his head. ‘No, I never. Is there no news of them?’

‘No. Not yet, anyway.’

Billy refused to be daunted. ‘We shouldn’t give up hope, Kath. There were so many men there, you can’t imagine. It’ll take ages for it all to be sorted out, it stands to reason. They could be in some town on the south coast or down in Kent somewhere, unable to get a message back home. You never know. It was a huge operation, blimey, I never seen so many men together in one place. Made me proud to be British, it did, that we could save so many of our boys and come back like we did.’

‘Of course.’ She poured the tea and didn’t stint on the milk, even though she was low on her ration. She added a heaped teaspoon of sugar to Billy’s. To hell with being careful. His return was something to celebrate.

‘I’m so glad you made it back, Billy,’ she said, passing him his cup, her voice full of emotion. ‘You were so brave to go off like that. Everyone thought so.’ Her hand brushed against his as he reached for the cup, and he caught her gaze.

‘It weren’t nothing more than all the others were doing,’ he said thickly. ‘I couldn’t have lived with meself if I hadn’t done it. But I’m glad you think I’m brave. Means a lot to me, that does.’

Kathleen cleared her throat. ‘I do think so, Billy. I really do.’ For two pins she would have crossed the mean little room and thrown her arms around him. But she couldn’t.

Even though she could read in his eyes plain as day what he felt for her, and if she was honest she’d known that for a while, she could do nothing about it. She had just lost her husband. Whatever sort of husband he had been, she had to respect him if only as the father of her child. She had loved him once with a deep and all-consuming passion, and knowing they would never share that again cut her deeply. How had she ever fallen for fickle, vicious Ray’s good looks over Billy’s quiet reliability? But she had, and couldn’t undo what she’d done so foolishly. If she gave in to the urge to welcome him back now, the guilt would haunt her for the rest of her life. She must not. ‘I do, Billy,’ she said again.

‘And you’re brave too, Kath. We all think so.’ He regarded her seriously. ‘If you need anything, you make sure to come to me. I’m sorry you’ve been left like this, sorrier than I can say, but you’ve got good friends. Just you remember that.’