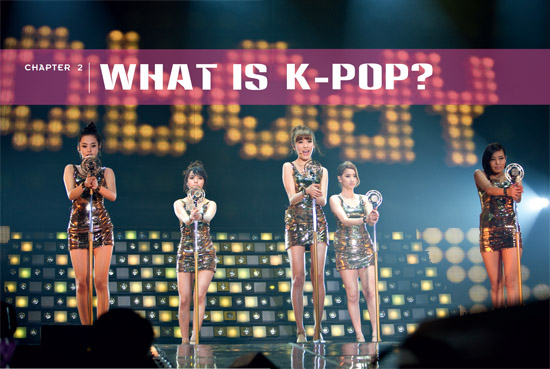

The Wonder Girls’ biggest hit, “Nobody,” featured a retro 1960s style.

If Korean music fans’ biggest question was when would K-pop break out in the West, in the West the biggest question has probably been “So what is K-pop anyway?” K-pop literally means “Korean pop,” as in pop music, but of course the term stands for much more than that.

At first glance, the beats and dancing and videos look familiar, much like a variation of American pop music. But the closer you look and the more you listen, the more differences you notice. Like when I heard a K-pop song in a Barcelona café, I could identify something different about it even before I heard the singers’ language. There is something distinct and special about K-pop. It’s like everything is a little bit louder, the images brighter, the style flashier—it’s just more.

Ever since the modern pop music industry began a century ago, it has been international, from the jazz of the 1920s to the rise of rock ’n roll to disco to the hundreds of types of music we have today. Much of the time, that has meant musical ideas arising in the United States and traveling to the world—but not always. The British Invasion, which brought the Beatles and the Rolling Stones to the United States, is probably the most famous example. Bossa nova, Brazil’s samba-influenced jazz that became very popular in the 1950s and 1960s, is a favorite of mine. Scandinavia has its heavy metal. And, today, Korea has K-pop.

So where did K-pop come from? Although the hip, exciting Seoul of today is rather new, it’s worth remembering that Koreans have long been a very musical people. Chinese diplomats returning home hundreds of years ago commented on how much Koreans love to sing. Even Korean traditional music was unique in East Asia for its focus on free-form, almost jazz-like improvisation and reinterpretation. Western music came to Korea in the late nineteenth century, bringing new scales and instruments, and jazz was quite popular in the 1920s.

In the aftermath of the Korean War of 1950–3, both sides of the divided peninsula were devastated, but soon Korea’s strong-willed, dynamic people began rebuilding their country. By the 1960s, South Korea was undergoing an artistic renaissance, and one of the most exciting aspects of that era was its music. Rock, folk and funk all flourished in the late 1960s and early 1970s as young people became caught up in the excitement of an all-new era. Sadly, though, this era would not last. South Korea’s government was quite authoritarian at the time and none too fond of the counter-culture elements of the day, so it cracked down hard in 1975. Many of Korea’s top musicians were sent to jail or drummed out of the music industry, leaving a very different music scene behind. Tastes also changed, and by the 1980s rock was much less popular, leaving ballads and plenty of cheesy synthesizers and syrupy pop music (not to mention oodles of oversized shoulder pads).

CAPTURING THEIR FAVORITE IDOLS

Through all these changes, Korea continued to transform. Its economy surged and expanded at an amazing rate. The military government came to an end in 1987, and the new constitution that came into being allowed greater freedom of expression and restored democracy. The Seoul Olympics of 1988 were a symbol of how much the country had grown and opened up. And thanks to the growth of the economy and freedom, Korean arts and entertainment were soon recovering.

BTOB IS A YOUNG GROUP BUT IT ALREADY HAS MANY FANS

There was popular music before K-pop, of course. Cho Yong-pil was one of the biggest artists of the 1980s, although he faded in the early 1990s before making a spectacular and totally unexpected comeback in 2013 with “Bounce,” a song that dethroned Psy from the top of the charts. Kim Kwang-suk was an important and influential folk singer, closely associated with the democracy movement. Sinawe was probably the biggest heavy metal group ever, peaking in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Kim Gun-mo was huge for much of the 1990s, although his more jazzy, grown-up pop songs never really fitted the K-pop mold. Shin Seung-hoon was the biggest ballad singer of the early 1990s, back when ballads ruled the charts. But none of these acts were K-pop, at least not the K-pop we would recognize.

The rise of modern K-pop couldn’t be clearer. It began on March 23, 1992, the day that Seo Taiji and the Boys released their first album. Seo Taiji (born Jung Hyun-chul) had dropped out of school at seventeen and briefly played with Sinawe before hooking up with b-boy dancers Yang Hyun-suk and Lee Juno. They formed a hip-hop group heavily influenced by New Jack Swing, but also a jumble of musical ideas, and featured plenty of energetic dance moves. Most older Koreans were confused by this new musical concoction, but young people loved it. “Nan Arayo” (“I Know”) spent most of the year on the top of the charts, starting a music revolution.

Seo Taiji was not the only one dreaming of new musical styles, of course. Another producer trying to figure out the new sounds of a new generation was Soo-Man Lee. Lee had been a popular singer, deejay and television host in the 1970s before leaving Korea to study electrical engineering in California. While he was studying engineering, he was also studying MTV and the biggest trends in American music, and working out how to bring these trends to Korea. Soon after returning home, Lee started SM Entertainment. He tried making stars of several promising young talents but was not quite able to find the magic formula.

MISS A MEETS WITH FANS

CUBE STUDIO

Not until he created H.O.T, that is. With H.O.T—short for “Hi-five Of Teenagers”—Lee combined the energy of new American pop music with a rigorous training system designed to create young stars. Lee realized that stars needed to learn more than just singing and dancing. They needed a whole range of skills, such as humility, attitude, language and the ability to deal with the media. H.O.T exploded on the scene in 1996, selling in huge numbers and whipping young fans into a passionate frenzy. Soon came more bands, such as the girl group S.E.S., Shinhwa and Fly to the Sky.

Lee was not alone. Yang Hyun-suk, one of the members of Seo Taiji and the Boys, started YG Entertainment in 1996. Daesung Enterprise (today’s DSP) had groups like FinKL and Sechs Kies. Park Jin-young launched his solo career in 1994, then started his own music label, JYP Entertainment, in 1997. With each new group, each new producer, K-pop was growing, becoming brighter and better.

It is important to remember that these trends and successes in music were not happening in a bubble. Korean movies, too, were ever more creative and celebrated, setting box office records and winning awards around the world. Musical theater boomed also, and today the live options are almost endless. In the arts, design, fashion and more, young talented Koreans were rewriting the notions of what Korea is and what it could do. And as each field grew, it would influence and fertilize the others, transforming the whole of Korean society.

G.NA

With the turn of the new millennium, K-pop continued to grow. Korea quickly installed one of the world’s best broadband Internet networks, which, while amazing for gaming and transforming day-to-day life in Korea, also meant that the Korean music industry bottomed out. Young people simply stopped buying music. Music stores disappeared. If they were to survive, Korea’s music labels would have to look at other ways of making money. Some pushed their artists into commercials and acting. Others focused more on international sales. Japan, being the world’s second biggest music market, was the obvious target, and SM Entertainment’s BoA was a prime example of doing great there. But many singers increasingly found fame around Asia, thanks in no small part to acting in popular TV dramas. Rain, who starred in the very popular Full House, is a great example of this trend. And China, although still a tiny music market, was growing rapidly, and Korea’s music leaders had their eye on it. This is where the term hallyu came from, coined by Chinese journalists to describe the popularity of Korean artists there. Called hanliu in Chinese and hanryu in Japanese (it’s all the same character, 韓流), hallyu literally means “Korean wave” or “flow,” and soon Korean music was washing over all of Asia.

But the wave didn’t stop there. As with Korean movies and TV shows, its music kept finding new fans. In the old days, you had to convince radio programmers or music television executives to play your music if you wanted people to discover your group. Not in the Internet age. Thanks to YouTube and other online services, fans were able to find anything they wanted and could spread the word. And the word kept spreading. If you are reading this book now, it’s probably because the word spread to you as well.

Today, SM Entertainment, YG Entertainment and JYP Entertainment are commonly called the “big three” music labels (with Cube, which was founded by a former JYP president, often considered a strong fourth). Each has a pretty distinct style of music and way of doing business. SM is easily the biggest company and concentrates on more bubbly, younger pop. Having consistently produced many of the biggest groups in K-pop for nearly two decades, it can be argued that SM is the industry leader and most aware of what the fans want. Except that SM might argue it doesn’t produce K-pop. It produces SM-pop—a style of its very own.

FANS HANGING OUT AT CUBE STUDIO

JYP ENTERTAINMENT

2PM

YG ENTERTAINMENT

JYP Entertainment has a more R&B flavor and is strongly influenced by its founder, JY Park (Park Jin-young). Park is the main songwriter for his company’s groups and the creative force. His mottos of leadership, humility and responsibility hang prominently on the walls of the JYP headquarters. He also has a long history of success, having been a big solo artist himself for many years and having worked with many of Korea’s top stars. JYP used to be home to Rain, one of the biggest K-pop stars of the last decade, and his group Wonder Girls were the first K-pop group to land on the Billboard charts.

YG Entertainment was founded by Yang Hyun-suk after Seo Taiji and the Boys broke up. From the beginning, YG featured hip-hop and favored attitude over the usual K-pop cuteness. But since YG struck gold with the idol groups Big Bang and 2NE1, it has pushed swag and flair to ever greater heights. YG is also home to a little solo artist by the name of Psy; maybe you’ve heard of him.

But there are dozens of smaller labels, too, all following roughly the same formula: recruit potential stars young, then train, train, train them incredibly hard, and put together the most promising recruits in a multi-member (and nearly always unisex) band. Almost everything is done in-house, from production to publicity.

BIG BANG

15&

So that is some history and background about K-pop. But it still leaves the core question unanswered: What is K-pop? There are very few signs of traditional Korean pentatonic music in it, or of Korean traditional instruments. Increasingly, top K-pop labels buy music from international producers (and some K-pop songwriters write for Western acts, too). Detractors, even Korean ones, often accuse K-pop of not being Korean at all. But if you listen to it seriously, there is definitely something different about K-pop that stands out.

It has certainly changed a great deal from the days of Seo Taiji and H.O.T. Tinny New Jack Swing is long gone, replaced with much more of an electronic dance sound, even dub step on some songs these days, most notably on CL’s “The Baddest Female.” There are still a few tinges of trot here and there, but much less than there once was. A popular trend at the moment is to create songs that almost sound like mash-ups of three or four different songs stuck together at random. Although this mishmash sounds weird to many ears, it’s a hyperactive style that has long been popular in Korean discos, where you often get just minute segments of a song before the deejay quickly moves on to something else. Apparently, even pop songs are not fast enough for the high-speed pace of young Korean people today.

FANS GATHER TO GLIMPSE THEIR IDOLS

Perhaps one of the most defining parts of K-pop is simply the language. Korean is a snappy, popping language, full of densely packed, tight syllables. In many ways, it is already halfway to hip-hop. Writing melodies for the Korean language forces the songs to reflect the language, often with more syllables in a line than you’d hear in other languages. And since dance and live performances are such an important part of K-pop, songs are also written with their choreography in mind. The things K-pop sings about are different, too. There is much less storytelling than in Western music and more of a focus on describing a feeling or metaphor. While there is plenty of longing and suggestion, K-pop is usually much less graphic and sexual than Western pop (well, except for JY Park).

Perhaps most importantly, K-pop is overwhelmingly genuine. It is not a music of cynicism. When a singer loves, he loves completely. When he misses his love, it is a deep, soul-crushing ache. And most of the time, it’s just fun. Sure, it can seem a little silly, even childish, but plenty of people appreciate the opportunity to forget about being cool and have a little fun.

If you have dreams of becoming a star yourself, there is good news as K-pop has gone global, and so has the search for new talent. And with new stars like 2PM’s Thai-American Nichkhun, Miss A’s Fei and Jia and SM Entertainment’s large and growing line-up of ethnic Chinese stars, K-pop is more open to the world than ever. Even non-Asians are increasingly getting chances at stardom now, with girl group The Gloss featuring Olivia, a French woman, and Nicole Curry appearing on the audition program Kpop Stars 2.

2PM

However, it’s still an incredibly tough slog. There are untold thousands, even tens of thousands, of young people fighting with all they’ve got to secure one of the few precious slots that open each year in Korea’s leading music labels to become a young trainee. Of the few that make it, fewer will actually get a shot, and fewer still will make it to the big time. Between that audition and becoming a star, a trainee is in for years of brutally tough training. Not to mention that they had better learn Korean fast and well.

Step one, of course, is the audition. These days, all the big music labels in K-pop recognize the importance of finding stars, so there are more opportunities than ever to try out for a precious slot. Many, like YG Entertainment, accept online applications any time, inviting the most promising young people to live auditions several times a year. The big labels typically have one or two auditions in the United States each year, and another in Japan, and auditions in Canada, Australia, China and other parts of the world are growing more common, but of course there are more chances in Korea.

What are the music producers and labels looking for? It’s more than just a great voice. It’s more than just dance moves. It’s more than just a pretty face. Everyone is hungry to find stars—that magical but oh so elusive charisma that inspires fans. And you had better be pretty young. It takes years to create a K-pop star, more than four on average, so the window of opportunity is fairly small.

BROWN EYED GIRLS

Once you pass the audition, now the hard work really starts—the training. Expect to face years of arduous work, improving your singing, dancing, languages and, most importantly, how to be a star. Expect long, long days, often going well into the night. Expect to sweat. Often labels expect you to live on-site, at small dormitories close to the main studio with many other aspiring young talents. It can be a fiercely competitive environment. “Cut-throat,” said Jay Park in Spin magazine.

School, however, is usually optional. Some labels, like JYP, insist their stars do well in school and encourage their talents to get into university. Others, however, leave such decisions up to the individual.

As for dating, don’t expect much. Both during training and after making their debut, artists are usually too busy to have much time to date. And, generally, music labels don’t want their stars to be tied down. Idols are presented to fans as a kind of virtual boyfriend and girlfriend, so relationships ruin the illusion, not to mention that overly enthusiastic fans have been known to go crazy on girls seen dating their favorite male stars.

With such a long, relentless process to craft a star, it’s difficult and expensive for the music labels. Dorms, food, classes, transportation, clothes and everything else adds up quickly, and it’s been estimated that training costs the music companies around $100,000 per student each year. With K-pop groups comprising so many members and taking so many years to train, it’s no surprise the management companies want to sign their recruits to such long contracts—as long as thirteen years and some even longer—and take such a large cut of the revenues. But some court cases and bad publicity have gradually chipped away at the worst types of long-term contracts. The truth is, once a performer becomes a star, the balance of power completely changes.

Television is also changing how K-pop stars are made, thanks to the popularity of American Idol-style audition programs. With artists like Lee Hi, Park Jimin, Busker Busker and Akdong Musicians rising to fame from TV, there’s a new business model coming to K-pop with the potential to change K-pop yet again, but so far it’s too early to know for sure.

One bit of more serious advice. With so many K-pop groups being formed, almost every day, not all the producers and managers out there are completely trustworthy, as is true about the entertainment business anywhere. So before you sign anything or agree to anything, make sure you’ve done your homework and selected carefully, and stick with people who have a well-established track record and a good reputation.

K-pop, like so much else about Korea, is constantly growing and changing. Whatever K-pop is, you can be sure that in a few years it will be something else. That is what makes K-pop so perplexing sometimes, but it is also what gives K-pop its power.

WONDER GIRLS

INTERVIEW WITH

Eat Your Kimchi

Simon and Martina Stawski’s Eat Your Kimchi is one of the most surprising success stories to spring from K-pop, or at least the neighborhood of K-pop. A newly married couple from Toronto, Canada, Simon and Martina came to Korea in 2008 to teach English in a Seoul suburb. To help sooth their families’ worries, they started making fun little videos about their lives in Korea. But soon they grew more ambitious and began covering other subjects, including K-pop, reviewing videos and interviewing groups.

Those videos gradually caught on and now Eat Your Kimchi is a genuine phenomenon, with 340,000 subscribers to their YouTube channels and more than 130 million views of their videos. When Simon and Martina turned to crowd sourcing to fund a professional studio in autumn 2012, they were shocked to discover dedicated fans donated the $40,000 they needed in less than seven hours, eventually pledging more than $100,000. “We’ve been crying just about all day,” they wrote on their website when it happened. “Wait: OK—started crying again.”

K-Pop Now: How did Eat Your Kimchi get started?

Simon and Martina (they answered the questions together): It was just a hobby at the beginning. At first, our audience was our immediate families in Canada. We were surprised when we got our first subscriber on YouTube, and thought to ourselves “wtf? Why is someone subscribing to us?”

Simon and Martina, the couple behind Eat Your Kimchi, have become incredibly popular video bloggers, in part because of their regular reports on the world of K-pop.

I think that’s when we started to think seriously about the possibility of other people using our videos, so we started to create basic videos for those viewers, like how to use your T-Card. We remembered the shortage of videos on Korea at the time we came here, and figured that we just wanted to help out with things like that.

KPN: And how did your videos become a big deal?

S&M: We still find it hard to believe that something big is going on. It still doesn’t really feel that way to us, you know.

Around the time that we started thinking of doing this full-time, we looked into the idea of producing regularly scheduled shows. “Music Monday” was the first show that we started, but since then we’ve made shows for almost every day of the week.

As for the point where our videos really took off, we can’t really say for sure. We didn’t have any big boom. We just steadily, very steadily grew. There was no viral video that brought in thousands of new people to the site and videos. We just, month by month, got more subscribers and viewers. That’s all. It was only at the two-year mark that we saw that we could possibly grow big enough, if we continued at our rate, to grow to the point of independence, you might say. Our site’s almost five years old now, and it’s really been only in the last year or so that things have started to really take off.

KPN: Did you have any training in programming or media?

S&M: We’re both totally untrained in programming. We have no formal education in it whatsoever. We just fiddle around with buttons until the screen does what we want it to do. We’re just very inquisitive and diligent, that’s all. Our video editor now is formally trained, and she keeps on using fancy pants terms and we’re always looking at her confused, and say stuff like “Oh! You mean the fadoodlydoo button? Yeah that’s a good button.”

KPN: You’ve started getting huge reactions from fans, like you were K-pop stars. How did that happen?

S&M: I think we were the most shocked last year when we went to the Google MBC concert, and after the concert we got swarmed by fans. It took us 45 minutes to leave when the walk would normally have taken two minutes. Seeing so many people, in real life, outside of the Internet, was really when we started saying to ourselves, “OK, something weird’s happening here....”

Just this Monday [May 20, 2013], when we arrived in Singapore, we had a very big crowd of people waiting for us at the airport, so big, in fact, that the police were called. That surprised the hell out of us, because that’s usually reserved for K-pop groups.

For us, we were so happy to see so many people and we wanted to talk with everyone, not scoot off and be anti-social.

KPN: How important was K-pop in building your popularity?

S&M: K-pop really helped get us out there, though it’s not our only thing. We do indie videos, travel videos, blogging, eating, etc., but our K-pop vids are where we’re at our funniest. The source material is just so easy to work with! So, since we’re more outgoing in those cases, and they’re more shareable, then we can see that we got popular that way.

KPN: Who are your favorite K-pop groups these days?

S&M: We really like the big acts from YG: Big Bang, 2NE1 and Psy, but we also like SHINee, Super Junior, U-Kiss, T-ara and Orange Caramel.

INTERVIEW WITH

Kevin Kim from Ze:A

Kevin Kim was born in Korea but lived in Australia for many years. But his homeland called, and after passing his auditions for Star Empire Entertainment, he soon found himself in the new K-pop group Ze:A and then the subgroup Ze:A Five. When he’s not singing and dancing with his groups, Kevin has acted in the musical Love Song of Gwanghwamun. He also hosts the Arirang Radio program Hot Beat, and stars in too many commercials to list. He was kind enough to talk to me briefly about becoming a K-pop idol.

KPN: What made a teenager growing up in Australia want to audition for K-pop?

Kevin: I became interested in K-pop when I was a teenager because there was the Korean wave in Australia.

My first audition was an acting audition for Martin Bedford Agency, which had famous actors such as Russell Crowe and Olivia Newton John. It was a valuable experience leaning how to act well like those people. For my K-pop audition, which was just my second ever audition, it brought me to Star Empire Entertainment.

KPN: What was the most unexpected part of the training?

I went through tough times with vocal and dance training because I was not flexible. Plus, understanding Korean culture and speaking honorific Korean were really difficult for me.

KPN: What was your first public performance like?

My first public performance with Ze:A was in Cheongju, the capital city of North Chungcheong province. We walked all over town promoting ourselves, putting up posters and talking to people. We also performed from the back of a truck, called a “wing car” in Korean. We did the wing car stunt for Ze:A fifty times all over South Korea. We just kept practicing and practicing, trying to improve our performance. We stayed up all night preparing to perform on that truck before every event, practicing and keeping each other’s spirits up.

Before getting on stage the first time, I was really nervous, but as time goes by I’ve gotten more confident and have developed myself, step by step.

KPN: What do you most want to do artistically and musically in the future with Ze:A?

All the members of Ze:A have developed themselves in several ways, as composers, actors, emcees and singers. I helped write the lyrics for one song, “Step by Step,” on our new album Illusion. I really want to be famous worldwide, like Michael Jackson, someone who I really admired, in the future.

Ze:A member Kevin Kim wants to be as famous worldwide as Michael Jackson was.

INTERVIEW WITH

Brian Joo from Fly to the Sky

Brian Joo and Hwanhee were part of one of the most popular K-pop groups of the early 2000s, Fly to the Sky. Although an SM Entertainment group, it was a bit unusual: it comprised a duo instead of a large group and they sang more ballads and light pop instead of electronica. After leaving SM Entertainment in 2004, Fly to the Sky continued for several years, with both Brian and Hwanhee releasing solo albums. Today, Brian continues to sing and entertain as well as host a radio show and much more.

KPN: How did you get involved in K-pop?

Brian Joo: I’ve wanted to be in the entertainment business since I was four years old but I really didn’t see myself going anywhere with entertainment in the United States while I was growing up there. Back then, the US wasn’t ready for an Asian musician, nor was it accepted. Even today, Psy has had one big hit in the US, but he’s not continually coming out with stateside music. So, when I had the opportunity to audition for a Korean record label, I didn’t want to lose my chance to at least try and see how far I could go.

My audition was pretty out of the ordinary. I didn’t actually sign up myself, but a friend saw a flyer and contacted the casting director and pretty much got the audition booked for me. I had no idea this friend had signed me up and she had no idea that I would be contacted, but I was and it all fell into place from there. And this was back in 1997.

The process was pretty much a typical audition, I guess. They wanted to get me on film singing, dancing, acting and speaking Korean, because they needed to know how well I spoke the language, seeing that I’m from the United States.

KPN: What was most different about the process compared to what you expected? What was hardest? The most fun?

Brian: I had no thoughts beforehand as I had nothing to compare the process with. I pretty much did as I was asked and it was a nerve-wrecking experience because I was only sixteen years old at the time. The fun part of it was when the casting director called me back and told me that a big-time record label wanted to see me in person and that they would cover all expenses for me to fly to Korea and back. I just thought to myself, if I don’t get picked or signed up, then at least I’ll get a paid vacation!

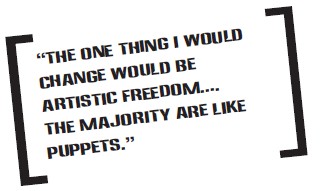

KPN: If you could change one thing about the Korean music business, what would it be?

The one thing I would change would be artistic freedom. I know a few musicians do what they want, but the majority are like puppets. Record labels make them perform the songs that they feel are right and they dress the boy bands and girl groups the way they feel fit. I feel that more freedom should be given to artists in Korea.

Brian Joo, as a member of Fly to the Sky, played a key role in the early days of K-pop.

KPN: Looking at K-pop today, what do you see as the biggest difference from when you first broke into the business?

Well, the biggest difference is that people from all over the world listen to K-pop and actually love the music. Back when I started, the Internet wasn’t so advanced and people didn’t realize what K-pop was. Back then, K-pop wasn’t called K-pop, it was called Gayo.

KPN: You are now very involved in CrossFit. How did you get involved in this? What is so special about it?

Brian: Well, I was always into fitness, but never found a way of working out that I really liked. Then a friend introduced me to CrossFit and I got deeply involved in it. The main reason I enjoy it is because it’s a challenge every time I do a CrossFit workout. And I see myself getting better day by day, so it’s definitely a healthy addiction that I don’t want to stop.