“If you try, you’ll find me, where the sky meets the sea.

Here am I, your special island. Come to me, come to me.”

LYRIC BY OSCAR HAMMERSTEIN

The war in the Pacific inspired a thousand pinups as morale boosters for the troops all over the world. Betty Grable, with her “one-million-dollar legs,” and Rita Hayworth—”the goddess of love of the Twentieth Century”—donned Lastex swimwear or lacy lingerie for the pleasure of the boys in service, and the boys at home. Ava Gardner (“the world’s most beautiful animal”) joined the pinup brigade as well, later in the decade, posing languidly in the studio, athletically on the beach.

The swimwear makers, in an effort to stand out in the crowded market, attempted to cultivate an in-house style in their advertising, with the help of the illustrators—and there were many at the time—who could individualize and romanticize their products. The full-color ads that were placed in Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Life, Look, and The Saturday Evening Post, were signed by talents such as Willard Cox, Frank Clark, and Lewis Baumer. The inexpensive movie magazines made do with plain-wrap, black-and-white illustrations. Jantzen employed a roster of commercial artists: Pete Hawley, McClelland Barclay, and George Petty—famous as the creator of the “Petty Girl.” The pinup master, Alberto Vargas, also worked with Jantzen, dreaming up his dream girls, radiant in sexy boned and wired suits, their shapely legs stretching to two-thirds of an ad page.

Christian Dior’s postwar “New Look” had an effect on American swimwear. The corseting, girdling, boning, wiring, and seaming associated with the uplifted and wasp-waisted dresses, translated into the very constructed look of bathing suits in the late 1940s and into the 1950s. But another evolution had already begun. For the Dolores Del Rio picture In Caliente (1935), Orry-Kelly dared the censors with the two-piece suit—the first onscreen—he designed for her; it was white, skirted, one-shouldered, and bared the actress’s tummy above the navel. The wartime restrictions on materials encouraged the popularity of the suit, as it used significantly less fabric than the classic maillot, even though the gap between top and bottom was just a matter of three to four inches. These few inches of skin, however, were much appreciated by connoisseurs of the female form.

Another excuse to show some extra inches of skin would be to film a fantasy about a mermaid, who would wear the equivalent of a two-piece: an embellished bra top with a spangled and scaled fish tail. For Mr. Peabody and the Mermaid (1948), Ann Blyth plays half of the title roles, winning the love of a married man on holiday in the Caribbean. An advantage to the situation: Blyth was petite, actually short, and the length of her mermaid’s tail would substantially elongate her figure, as she posed on the rocks. The movie company went on location, but not to the Caribbean: the crucial ocean and shore scenes were filmed at Weeki Wachee Springs in Florida.

It was an American woman, sportswear designer Claire McCardell, who first offered, in 1935, the two-piece in the marketplace. Like Chanel, she was known for her wool jersey separates, but McCardell’s were said to have a very “American look”: spirited, surprising, more than a little dashing. She devised the first tube top, the first unitard, and her swimsuits were a bit experimental, involving, among other effects, neoclassic draping and loincloth gathering.

Specializing in resort and cruise wear, Tina Leser moved her business from Honolulu to Manhattan, but still incorporated her ethnic sensibilities into her work by way of sarongs; harem, dhoti, and toreador pants; and hand-painted Hawaiian prints. Leser developed a celebrity clientele which included Joan Crawford, Joan Fontaine, and Paulette Goddard.

Designer of beach and play clothes, Carolyn Schnurer worked mostly with varieties of cotton fabrications rather than the elasticized synthetics. She was a world traveler, seeking inspiration globally, to design for the label Burt Schnurer Cabana. One scintillating image took Schnurer to the next level. Photographer Toni Frissell—a rare woman behind the camera—captured model Dovima, oiled and glamorously exhausted in the tropical heat, and wearing a soft dotted cotton bandeau bikini, perhaps Schnurer’s first. Shot at Montego Bay in Jamaica, the black-and-white photo was published in Harper’s Bazaar in May 1947. The accompanying caption to the Frissell image advised, “One wonderful way to take the sun . . . completely covered with ‘sutra’ lotion to filter out the burning rays. . . .”

Sun tanning had become serious business by the late 1940s. From the 1920s on, it was no longer considered déclassé. A tanned face, neck, arms, and hands had been signifiers of the lower classes, those who had to work outdoors for their livelihoods. The 1920s flipped the script; Coco Chanel returned to Paris from Deauville in the south of France with a very attractive, healthy glow. The story may be true, and since then a beautiful tan has been an indication of wealth, leisure time, and resort living. Sunbathing’s dangerous consequences were unknown decades ago. The big concerns were the painful burning and the subsequent premature aging of the skin, even with all the oils and creams and lotions.

More skin exposure, more attractive tan lines, and heightened sensuality were the catalysts for ever briefer swimwear. In 1946, in Paris, couture designer Jacques Heim unveiled his tiny two-piece design to an interested press corps. But when Louis Réard, a civil engineer and design dilettante, showed off his version at the Molitor spa pool just weeks later, the news raced round the world. Booking a model to wear his invention proved impossible, so he recruited an exotic dancer, Martine Bernardini, to fill out his four triangles of cloth, and called it “the bikini,” after the group of little atolls in the South Pacific where atomic testing had recently taken place.

Réard was expecting explosive effects on contemporary swimwear, and on the culture at large, and spoke of it as “smaller than the smallest swimsuit. A bikini is not a bikini unless it can be pulled through a wedding ring.”

For the true “itsy bitsy” bikini to successfully cross the pond and appear on American beaches, another ten to twelve years would be necessary. Diana Vreeland stated that “The eye must travel,” and in transit, must adjust.

Ava Gardner, 1944. Photo by Clarence Sinclair Bull.

David Wills

Dorothy Lamour, early 1940s.

Rex / Shutterstock

Rita Hayworth, 1942.

Rex / Shutterstock

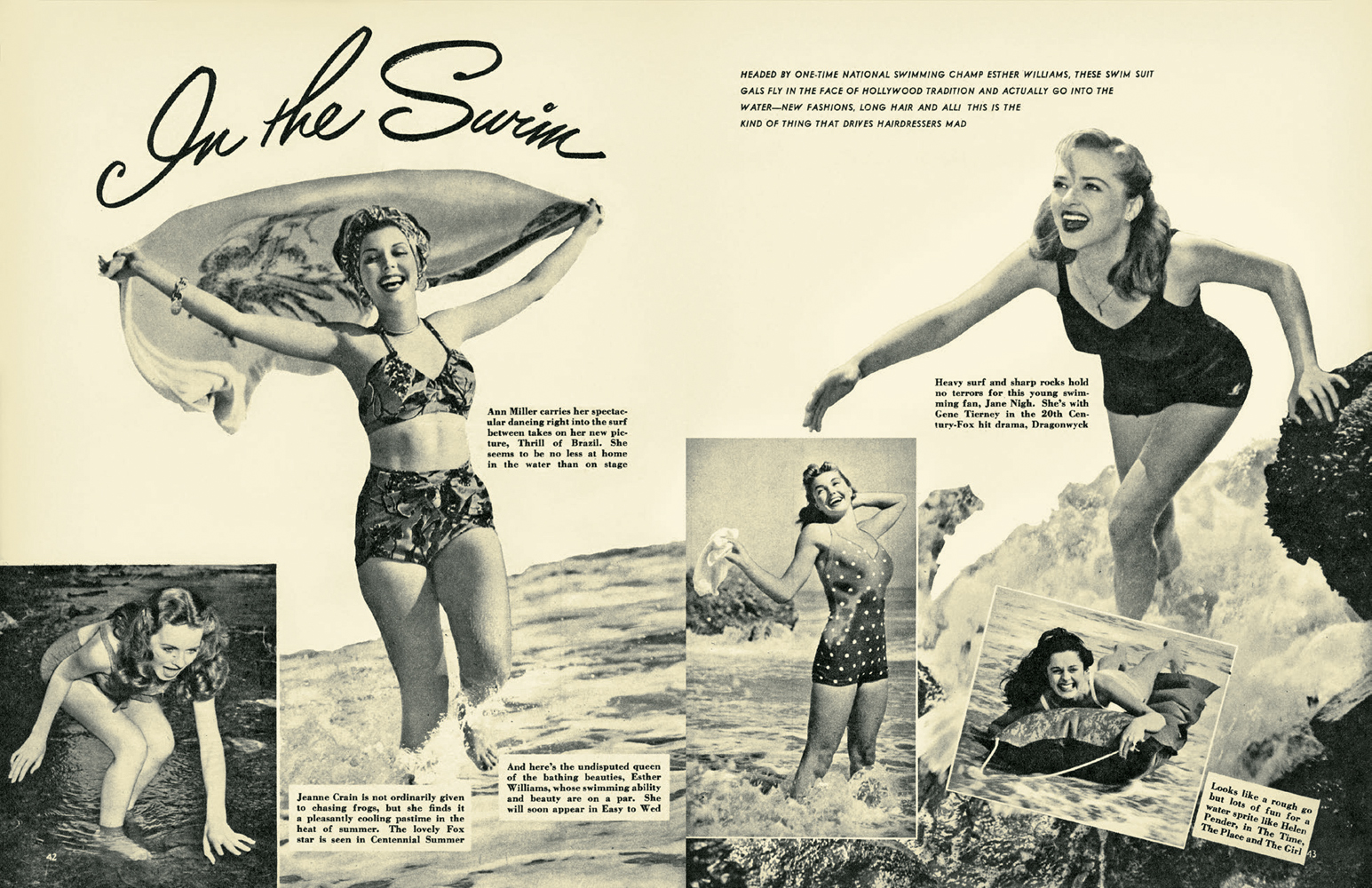

Article from Motion Picture magazine, July 1946.

David Wills

“Curve: the loveliest distance between two points.”

MAE WEST

Alexis Smith, 1941.

Everett

THE LONG AND THE SHORT OF IT: Joan Crawford on Waikiki Beach, Hawaii, 1949.

David Wills

THE LONG AND THE SHORT OF IT: Starlet, 1940s.

Everett

Ann Sheridan endorsing Royal Crown Cola, late 1940s.

Getty Images

RED TIDE: Jeanne Crain, 1944.

Rex / Shutterstock

RED TIDE: Rhonda Fleming, late 1940s.

Everett

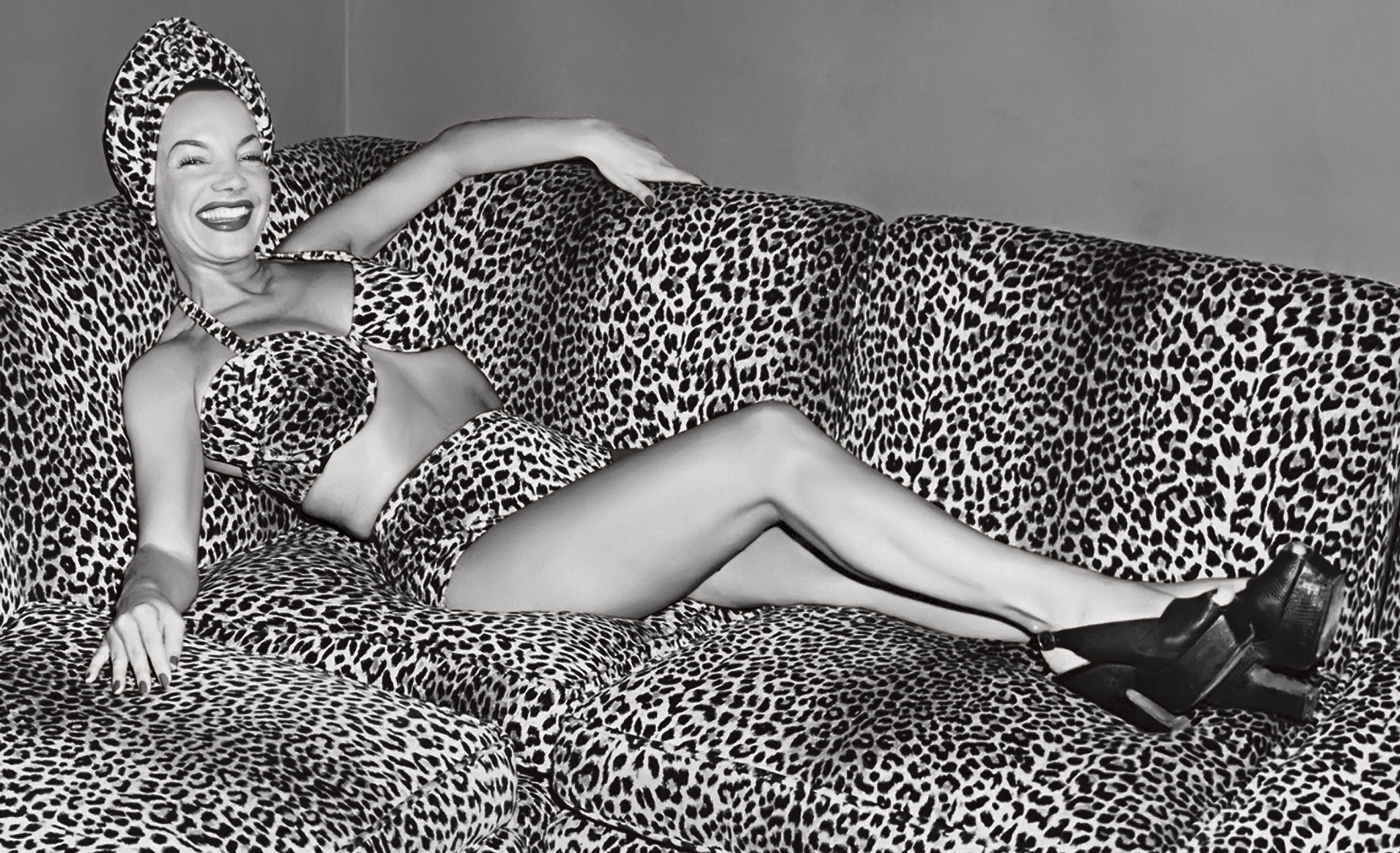

“Look at me and tell me I don’t have Brazil in every curve of my body.” CARMEN MIRANDA

SECOND SKIN: Carmen Miranda, unleashing her inner animal, at her beach house in 1948.

David Wills

Advertisement for Cole of California, 1948.

David Wills

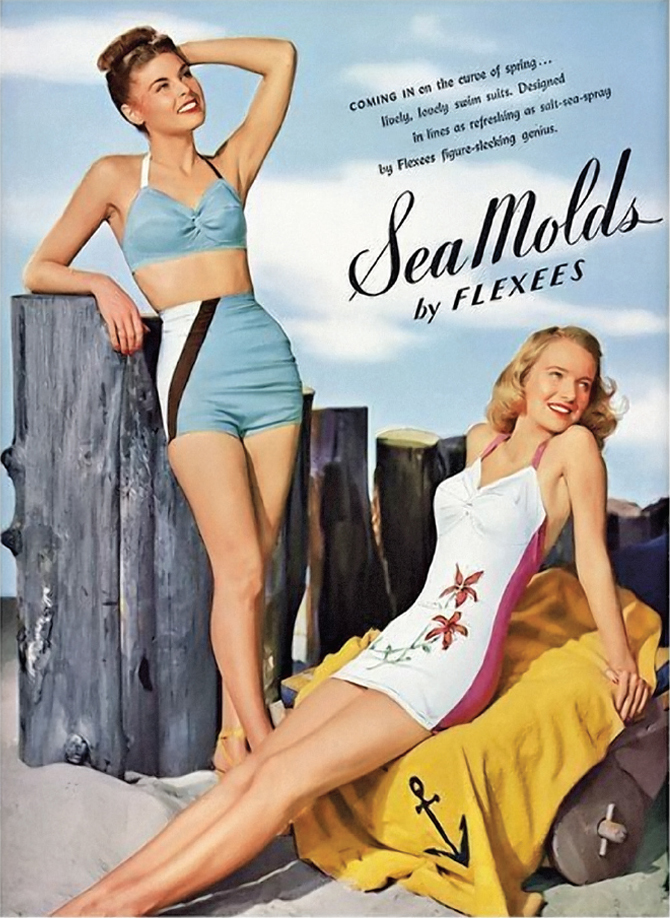

Advertisement for Sea Molds by Flexees, late 1940s.

David Wills

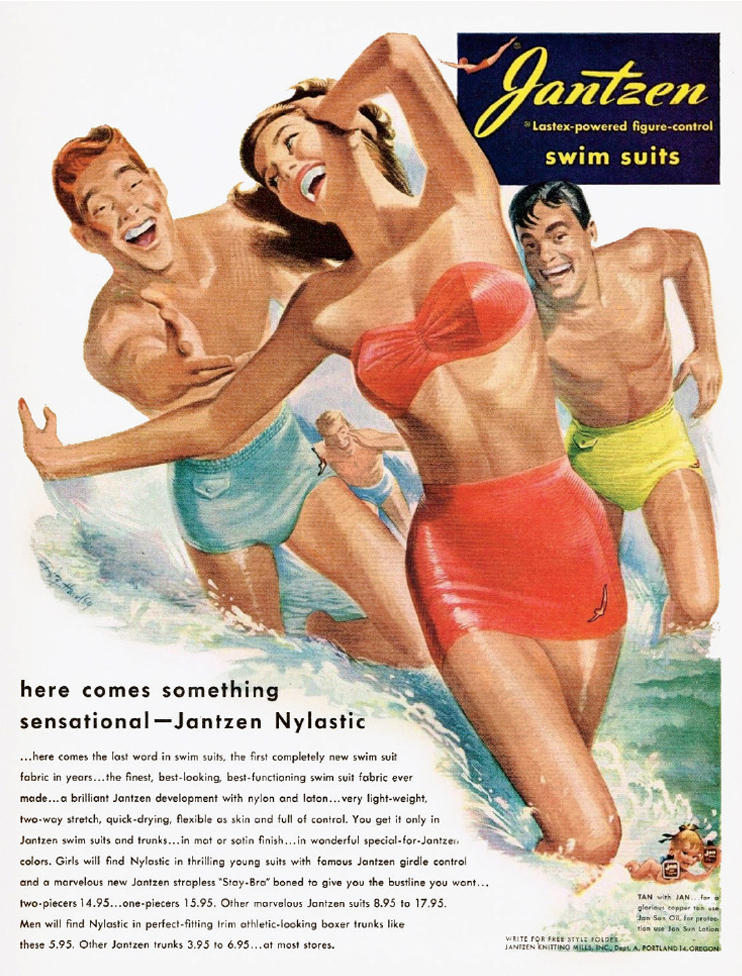

Advertisement for Jantzen Swim Suits, illustrated by Pete Hawley, 1949.

David Wills

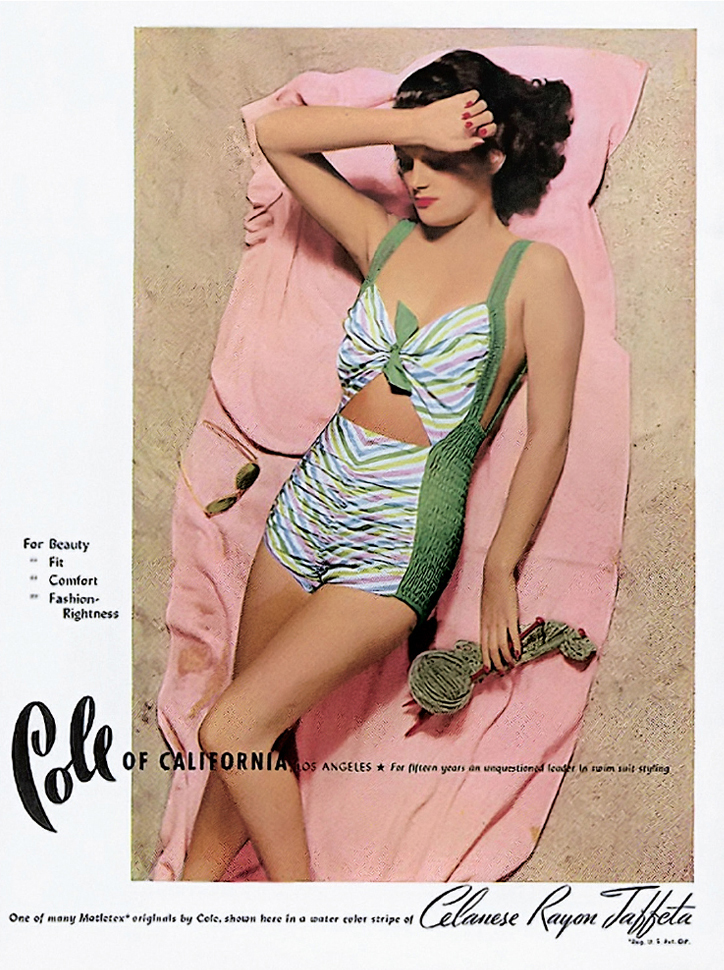

Advertisement for Cole of California, 1942.

David Wills

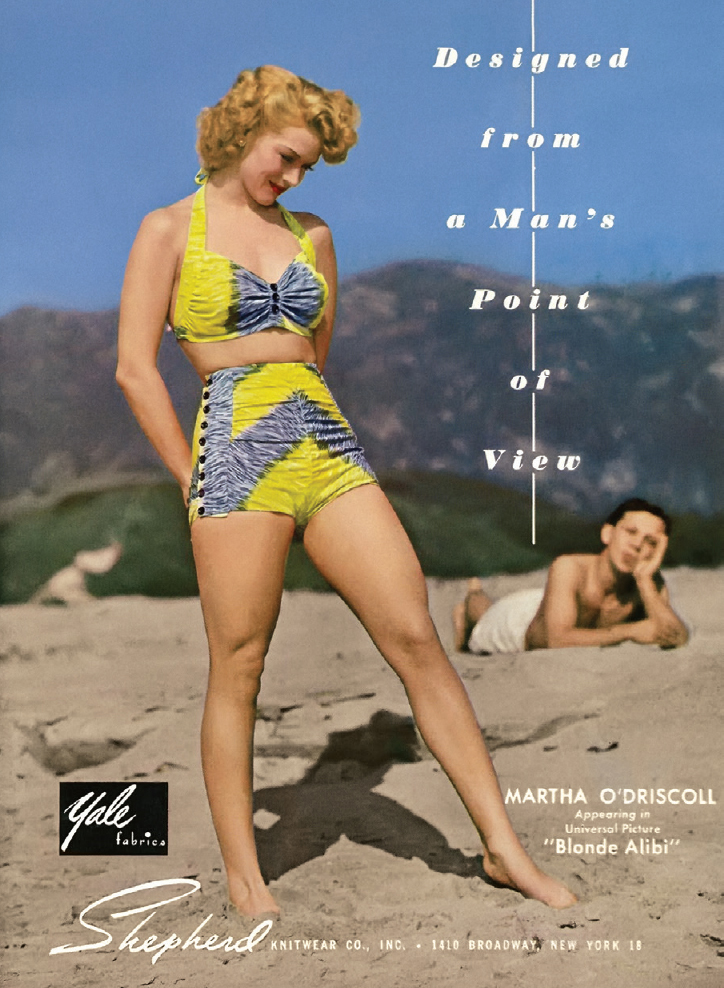

Advertisement for Shepherd Knitwear, featuring Martha O’Driscoll, 1946.

David Wills

Veronica Lake, 1942. Photo by Eugene Robert Richee.

David Wills

“I will have one of the cleanest obits of any actress. I never did cheesecake like Ann Sheridan and Betty Grable. I just used my hair.”

VERONICA LAKE

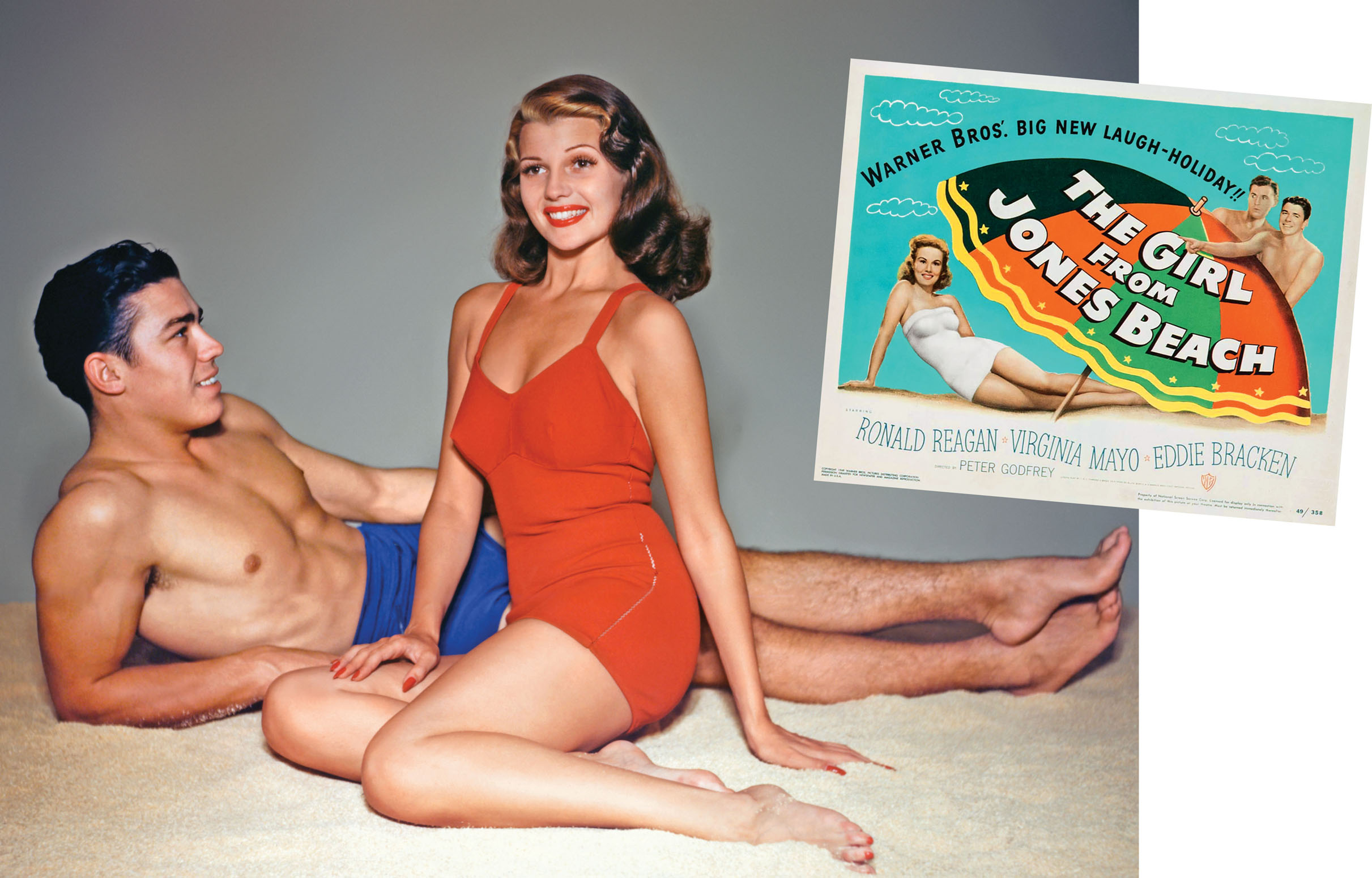

(LEFT) Rita Hayworth and her brother, Vernon Cansino, early 1940s. (RIGHT) Lobby card featuring Virginia Mayo, Ronald Reagan, and Eddie Bracken in The Girl from Jones Beach (1949).

David Wills

CROWNING GLORIES: Lucille Ball for Royal Crown, 1946.

David Wills

CROWNING GLORIES: Betty Grable for Royal Crown Cola, 1944.

David Wills

Shelley Winters, 1947.

David Wills

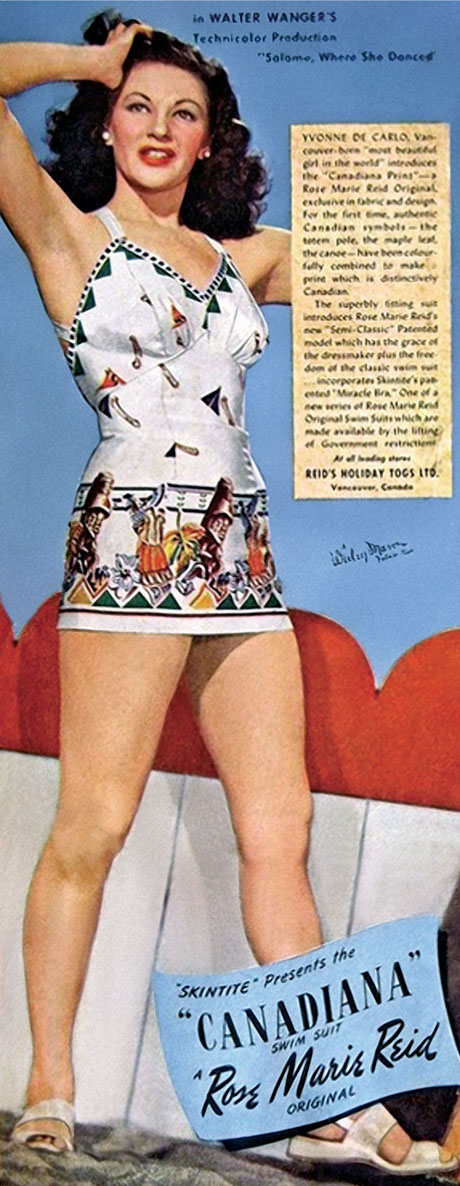

Yvonne De Carlo, late 1940s.

David Wills

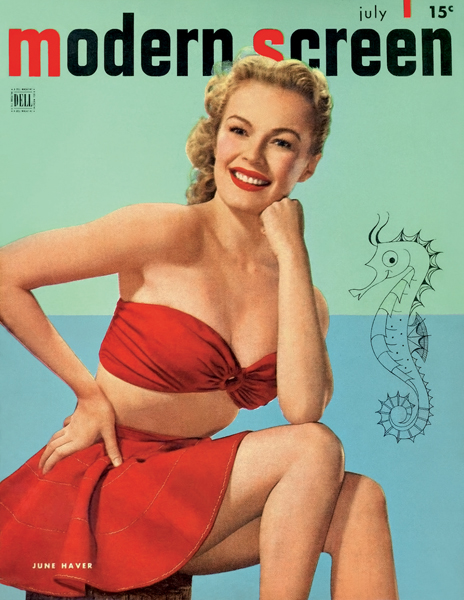

BANDEAU AND BAMBOO: June Haver, 1945.

David Wills

BANDEAU AND BAMBOO: Susan Hayward, circa 1944.

David Wills

“Doing nothing feels like floating on warm water to me. Delightful, perfect . . .”

AVA GARDNER

Ava Gardner, circa 1944.

Independent Visions / MPTV (mptvimages.com)

DOUBLE YOUR PLEASURE: Jane Russell in a Lastex swimsuit, 1948.

David Wills

DOUBLE YOUR PLEASURE: Russell in 1946.

David Wills

Carole Landis, 1943.

Rex / Shutterstock

Yvonne De Carlo in an advertisement for designer Rose Marie Reid, 1945.

David Wills

June Haver on the cover of Modern Screen, July 1948.

David Wills

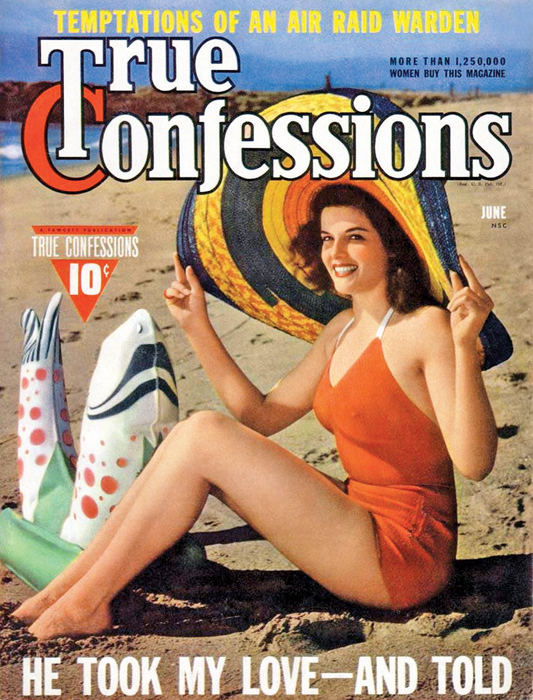

Jane Russell, True Confessions, June 1942.

David Wills

Marilyn Monroe, not quite on the brink of superstardom, as a young model in 1947.

David Wills

Popular World War II pinup Chili Williams, nicknamed “The Polka-Dot Girl,” featured in an article for Life magazine, November 22, 1943.

David Wills

Lana Turner as Cora Smith in The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946).

David Wills

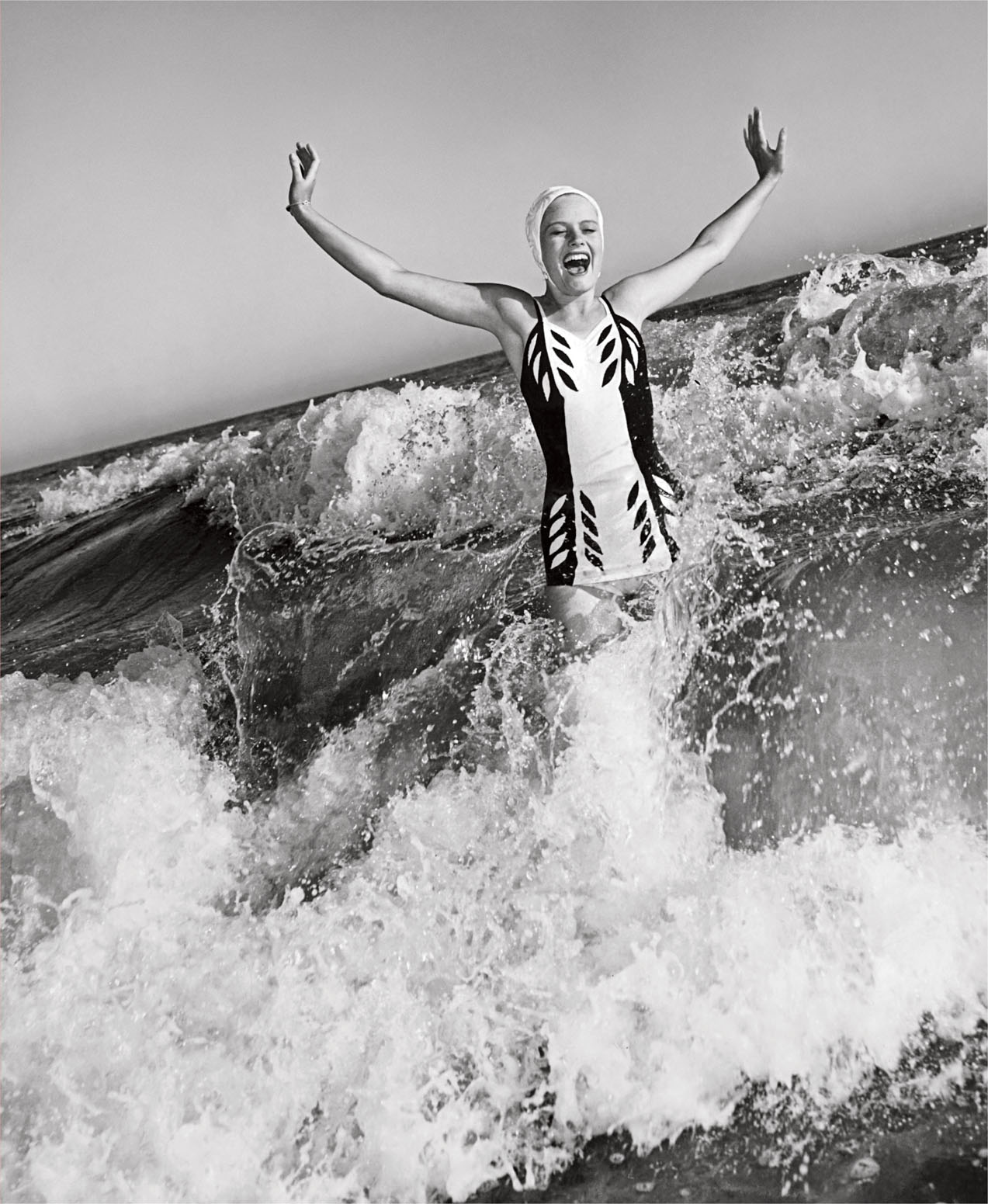

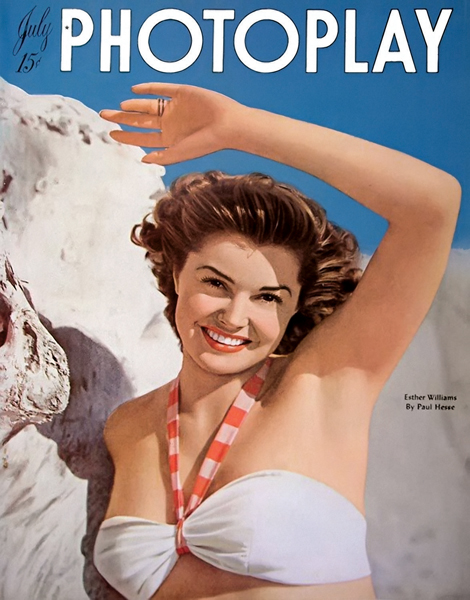

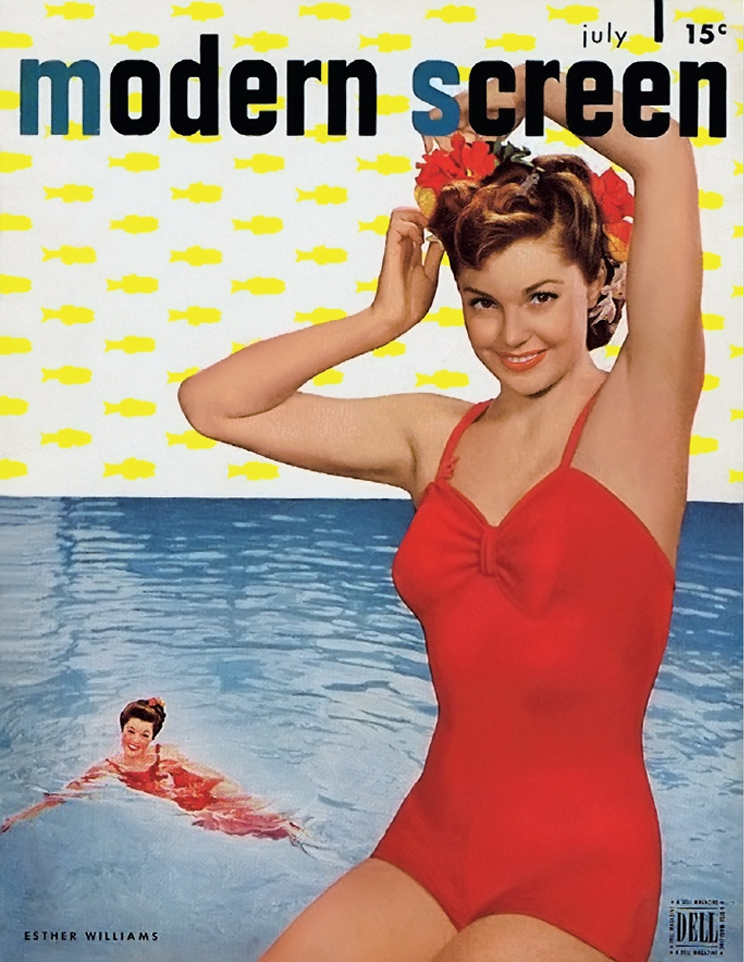

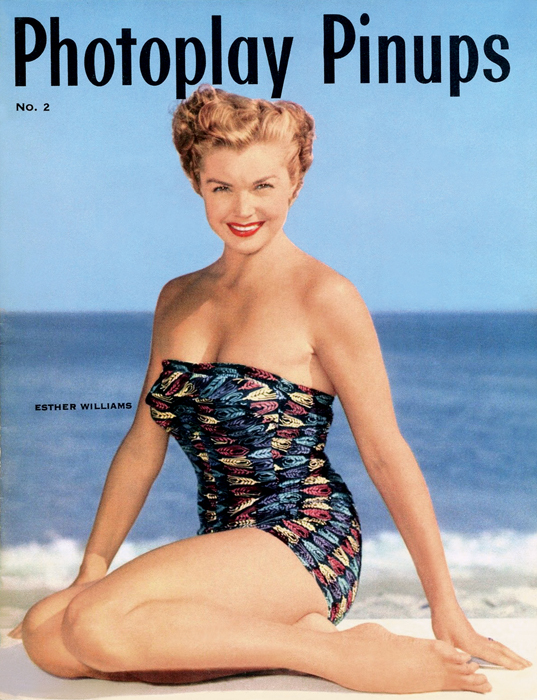

MILLION DOLLAR MERMAID: Champion swimmer Esther Williams captivated cinema audiences with her aquatic spectacles in blazing Technicolor, including Bathing Beauty (1944), Neptune’s Daughter (1949), and Dangerous When Wet (1953). (ABOVE) Belgian movie poster featuring Williams with Peter Lawford in On an Island with You (1948).

David Wills

Williams on the cover of Photoplay, July 1947.

David Wills

Williams on the cover of Modern Screen, July 1947.

David Wills

Williams on the cover of Photoplay Pinups, late 1940s.

David Wills

Williams on the cover of Silver Screen, July 1947.

David Wills

MINT CHOCOLATE CHIP: Marilyn Monroe, circa 1947.

David Wills

MINT CHOCOLATE CHIP: Marilyn Monroe, circa 1947.

Everett

“The two-piece swimsuit was born in the wartime years, out of fabric-saving necessity. . . . The unspoken but golden rule was that the navel should always be covered. This was to prove the crucial difference between the two-piece and the bikini . . . [which] the major swimwear brands in the USA avoided like the hot potato it was for some time. A staid conservatism still existed at the center of American society . . . which contradicted the strong, sexy image of Hollywood that was evident in every small-town cinema.”

SARAH KENNEDY, Author and fashion journalist.

Gene Tierney, 1945.

Rex / Shutterstock