Reinhard Voigt

Reinhard Voigt

Change is timeless. A good restaurant is alive. It lives, it grows and so do its recipes.

In the twenty-two years since we wrote our first cookbook or “the blue book,” as it has become known, much has changed—the way we eat, the way we shop and the way we cook. There has been an explosion in the availability of ingredients. Vegetables arrive daily from the Milan market, mozzarella is flown in from Naples, people grow herbs in their window boxes and salad leaves in their gardens.

Everyone is a chef.

Our first book, The River Cafe Cookbook, was written originally to be a manual for our own chefs to follow. But, as chefs, we have grown as well. We have traveled all over Italy, from Piemonte to Sicily, discovering new ingredients, new methods and, most of all, new people to expand our knowledge of the food we love. So, in thirty years, our book has changed.

To celebrate our thirtieth birthday, we returned to our first recipes in the blue book. Here we share our knowledge and experience of how we have refined those classic dishes.

Mixed in with the revisited classics are more than thirty new recipes created through our work and travels together: Mezze Paccheri, Black Pepper and Langoustine, an eccentric combination of langoustines with Pecorino; White Asparagus with Bottarga Butter, a variation on the classic anchovy sauce; and Crab and Raw Artichoke Salad.

The design of River Cafe London, by Anthony Michael and Stephanie Nash, is inspired by the bold art, architecture and bright colors of the restaurant—the pink wood oven, the yellow pass, the blue carpet. The Joseph Albers font, throughout the book, reflects these qualities.

Matthew Donaldson photographed the food on sunny days in our garden. Jean Pigozzi, who took the dynamic black-and-white photographs of the restaurant in action for our first book, returned to capture the customers, chefs and waiters who are the River Cafe family.

River Cafe London is the story of a restaurant that began with two unknown chefs and a space large enough for nine tables.

We have grown. We have a new vision, but the same conclusion: with good ingredients and a strong tradition, change and recipes can be timeless.

In 1991, Ellsworth Kelly drew a still life on the

back of a River Cafe menu and, on another,

a self-portrait, looking in the mirror of the

men’s bathroom.

Cy Twombly, in his distinctive hand, wrote

“I love lunch with Ruthie” on a menu, after a

long Sunday lunch celebrating his exhibition

at the Serpentine Gallery in 2004.

For this book, we asked the artists in the

River Cafe’s extended family to draw or

paint on a menu.

There is a connection between art and

food, and these works are unmistakably an

expression of each artist.

We love cooking for them:

Peter Doig, Susan Elias, Damien Hirst,

Brice Marden, Michael Craig Martin,

Ed Ruscha, Reinhard Voigt, Jonas Wood.

We thank them for making River Cafe London

a more beautiful book.

Richard Bryant

So, how did it all begin thirty years ago?

In March of 1987, Rose Gray and I met for a coffee. I wanted to tell her about a space that had come up in Thames Wharf where Richard Rogers and Partners had just bought a group of warehouses to convert into offices for their architectural practice.

We met on the Kings Road at Drummonds, which today is McDonald’s—so you could say that The River Cafe was actually conceived in a McDonald’s. After the coffee, we went to look at the space available. There were three floor-to-ceiling windows facing south over the Thames and room enough for nine tables. There was a communal green space in the middle. We imagined a vegetable and herb garden. We fell in love with the place, in love with the idea.

And so it began.

Rose, Richard and I became partners. Richard did the drawings, the lights came from The Reject Shop, chairs from Habitat and secondhand ovens from a yard in Coventry. Rose’s husband, the sculptor David MacIlwaine, who worked with wire, designed our logo. My brother Michael had our menus printed onto baseball caps, which he sent us from L.A. My sister Susan’s paintings were on the walls.

We called it The River Cafe. The imaginary garden became real and we planted wild arugula, the seeds brought home from a holiday in Tuscany. Our children worked with us—Rose’s and mine.

Bo was three at the time.

It was a family affair.

If restrictions can drive creativity, then we definitely had ours. The Hammersmith planners allowed us to be open only at lunchtime and available only to the architects, designers, model makers and framers who worked in the warehouses—people who usually had nothing but a sandwich for their lunch.

We made hamburgers, but with mayonnaise using extra virgin olive oil, and sandwiches with taleggio. We also made Pappa Pomodoro, which no one ate. As one customer said, “I’m not paying £3.50 for some stale bread and tomatoes.” We grilled squid and put it with arugula and fresh red chile. It has been on the menu ever since. We found a recipe for a cake and called it Chocolate Nemesis.

The only thing we didn’t make was money. With every sandwich and leftover soup our overdraft increased. How long could we survive? The worst day was when a young woman came on her bicycle selling sandwiches to all the offices for 25 pence cheaper than ours. We told her she was trespassing and asked her to leave.

Actually, we were treated as trespassers. A petition was sent to the council, signed by 100 people, complaining, “The River Cafe and its clientele are seriously diminishing the tone of the area.” Fortunately, we also had our fans. Fay Maschler, the food critic for the Evening Standard, wrote a review saying, “I am going to tell you about a restaurant run by two women with no professional experience, miles from anywhere, that you are not allowed to go to.”

Word spread. We stopped making sandwiches. We were allowed to open to the public; a year later, to open at night until eleven; a year after that, on the weekends. We became a restaurant.

But The River Cafe is not just about the food and the wine; it is also about the people who come to eat here and the people who work here—the true vital ingredients. I often wonder what happened to the man who asked us to make a cake with the words “will you marry me” and then canceled the cake halfway through the meal; the woman who used her mobile phone on a busy Sunday to call reception to summon a waiter to her table; the television journalist who took her shirt off in the middle of the restaurant because she lost a bet; and the American who wanted a taxi and when I asked where she was going said, “London.”

The River Cafe began with family, and it is still a family. The space has grown and the family has grown. Now, Sian Wyn Owen, Joseph Trivelli, Charles Pullan, Vashti Armit and I head a team of 100 brilliant people.

Thirty years later, we are still here in our beautiful garden with our view over the River Thames.

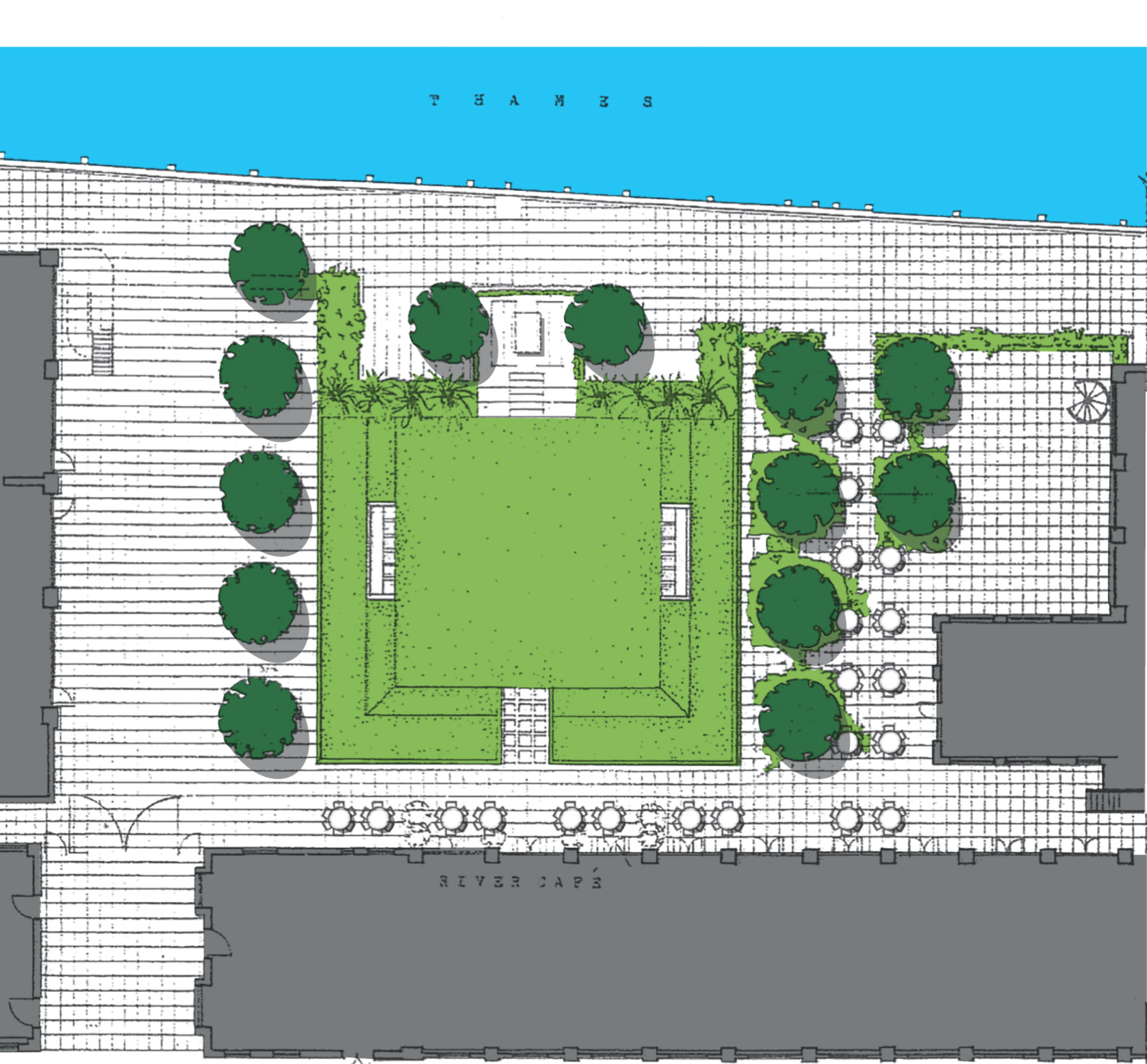

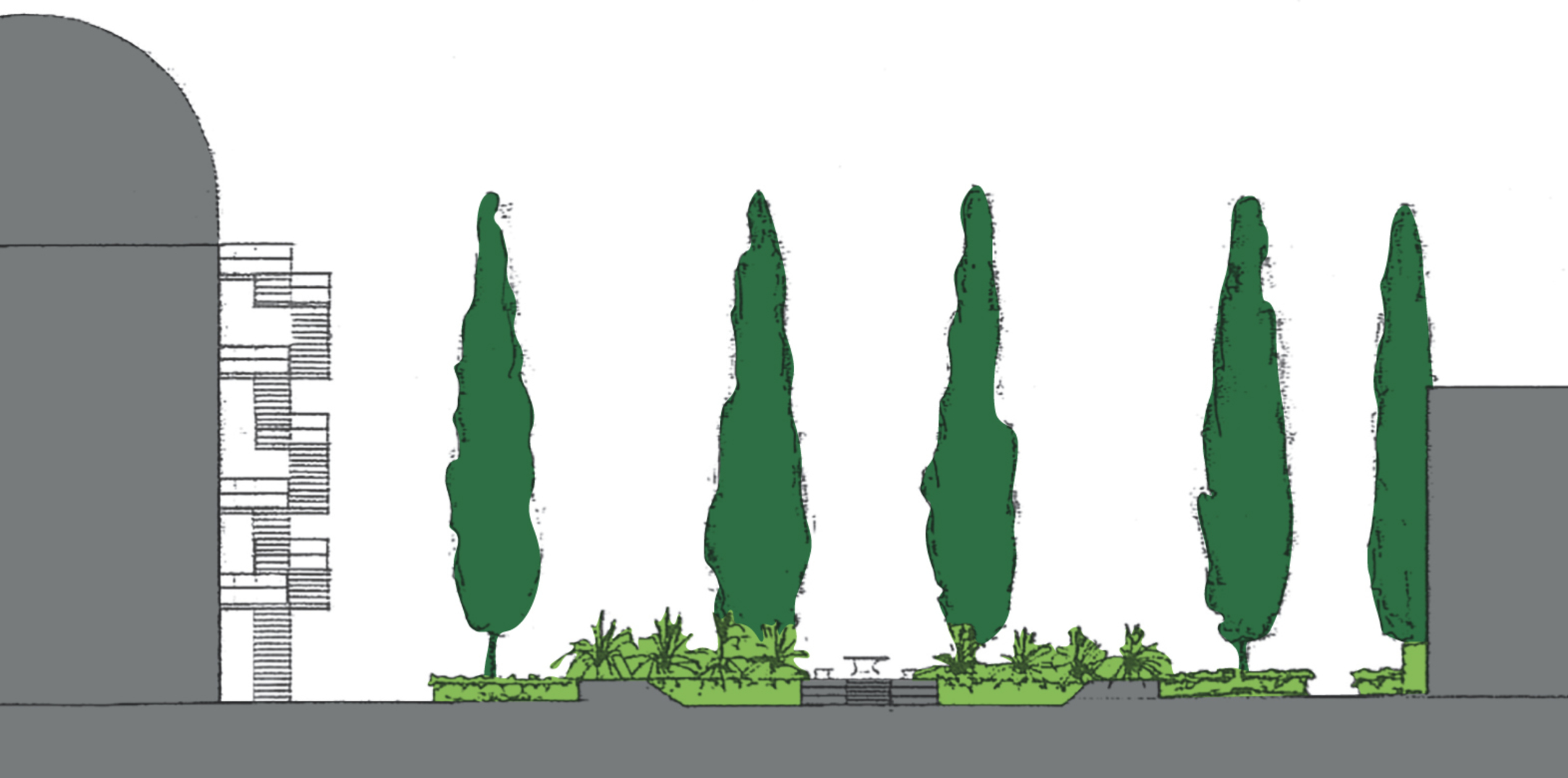

This is how we began—on a site that was previously an oil depository.

The growth of a restaurant.

Drawings by Stephen Spence

James Bedford

One of our first menus

Original plans for the garden by Georgie Wolton, 1987

Rose is in The River Cafe, in everything we do.

She is in the way we season the lamb before we put it on the grill. She’s there in the way we roll out our pasta dough and slow-cook our vegetables. She’s in the yellow color of the kitchen pass and the white tulips at the end of the bar. All this, and more, keeps Rose alive.

The first time I met Rose was in London in 1969. I was tagging along with a friend who had to drop something off at her house. We were shown into a room full of people. And then Rose entered. She had long red hair, a drink in one hand and a baby on her hip. I saw her and the room became different. “Who are you?” she asked me. This was Rose: presence, confidence and unedited directness.

Rose brought excitement, energy, curiosity, glamour and grace to our lives. She had posed for a photograph with a cigarette dangling from her lips and had acted in a movie. She had traveled with her husband, David, to Sri Lanka, Morocco and Mexico.

Rose moved to a farmhouse in the hills above Lucca in 1976 with her family. There, she immersed herself in the food of the region, created an Italian vegetable garden, learned how to make penne arrabbiata from the cook in her village bar and fresh pasta from the woman who came to help in the house. In the pasta chapter, you can see her drawings.

Rose’s conviction always convinced me. On one of our first wine trips with David Gleave, she said, “Ruthie, this wine tastes of chocolate and cigarette smoke. What do you think?” I replied, “Rose, this wine tastes of chocolate and cigarette smoke.”

Rose didn’t like the story about The River Cafe’s first days as a staff canteen. In her far-seeing, ambitious mind, we were always going to be the best Italian restaurant of our own, uncompromising, conception. She told a journalist two years after we opened, “Getting Italian Restaurant of the Year isn’t good for us. Just today, two people came in who had read about us and because there was only one pasta on the menu left in a fury. Frankly, I was thrilled to see them go.”

I miss the judgments passed in Rose’s gravelly drawl. She said what she thought, and there was little editing. Too original and, above all, too independent, she seemed to have a phobia of being “impressed” by people.

A grand winemaker once told me it took two olive trees to make a bottle of olive oil. I reported this back to Rose. “He is a liar,” she said.

My partner was competitive. I knew I could ruin her day simply by telling her I had had a good meal in another restaurant. At a restaurant considered one of the best in Piemonte, I asked Rose what she thought of the food. She answered in a loud serious voice, “I think the chef really needs to learn how to make polenta.”

How many times did I want to say to the recipient of one of Rose’s comments, “She didn’t really mean it”? But I didn’t. Because she did.

Rose was a visionary, a forward-thinker who pushed the boundaries: we should serve mozzarella with nothing else on the plate; we should serve fava beans that you pod yourself; we should have a cheese room; let’s grow borlotti beans in Hammersmith; why not create a cocktail and call it the Telefonino?

She broke barriers and had a disregard for the rules. On the way back from one of our many wine trips to Italy, Rose smuggled a fresh cotechino sausage through customs. She was stopped. She claimed it was for her dying mother. Then there was the pumpkin, more than half a meter in diameter, that she saw at Selvapiana Vineyard and had to have. The pumpkin traveled to London in a business-class seat. We sat in economy. People might try to resist but ended up doing what Rose told them to do—either from exhaustion or the realization that she was right.

In an interview Rose once said, “Growing herbs is essential for a civilized life in the city.” In those words, Rose is concerned, above all, not with food but with what it means to be civilized. And life, by and large, caught up with Rose’s vision for it.

Getting into a black cab in the early days, anywhere in London, Rose would simply say, “Take us to The River Cafe,” and I would pray that the driver, for his own sake, would not have to ask where it was. Thirty years later, I think of her every time I say the same words and I don’t need to follow with an explanation of where it is.

Our staff got the same tough love, but it was love—uncompromising love. If they did something she didn’t approve of, Rose spoke to them as if they were wayward children in an extended family. She was passionate about food and passionate about sharing her knowledge with everyone who wanted to learn. She was an extraordinary teacher.

Although people often tell stories about Rose’s, shall we say, “direct approach” and strong opinions, what I remember most about my partner was her gentleness and sweet patience. I can hear her now explaining how to cut a piece of Parmesan, prep a leaf of cicoria (chickory) and describe in minute detail after a wine trip how Vin Santo is made. I can see her demonstrating how to park a car and wear a skirt.

If we at The River Cafe are better chefs, waiters, kitchen porters, sommeliers, managers or, indeed, car parkers and skirt wearers, we can thank Rose Gray.

When, in December 2009, we were awarded an MBE, Rose said, “Ruthie, we are going to wear Chanel suits to the palace.” For an ardent anti-establishment rebel, Rose was totally thrilled. David said that she felt proud of the recognition and that she cried.

Seeing how ill Rose was, I suggested that the Palace bring our meeting with the Queen forward from June to February. But when I told Rose she said, “No, no, let’s not go then, Ruthie. Let’s go in June—I’ll be better then…”

…

I can still clearly see Rose coming in for her night shift, walking along past the bar, tapping the top of it absent-mindedly as she goes—no hellos, or eye contact, her mind only focused on the menu for that evening.

Rose is still here.

In everything we do.

She always will be.

Ruthie Rogers

David Loftus