At the end of Gary Snyder’s book Mountains and Rivers without End, he offers a glimpse into his understanding of poetry’s role in transmitting Buddhist dharma (teachings):

The T’ang poet Po Chü-i said, “I have long had the desire that my actions in this world and any problems caused by my crazy words and extravagant language [kyōgen kīgo] will in times to come be transformed into a clarification of the Dharma, and be but another way to spread the Buddha’s teachings.”

Snyder then writes, regarding his own work, “May it be so!”1

For Snyder, poetry (especially Chinese and Japanese poetry) is a vital resource for transmitting Buddhist dharma 法, fa (or 佛法, fofa). The term 法(fa) , like 空 (kong) and 文 (wen), is complicated and signifies different concepts within a wide range of cultural discourses. In Buddhist discourses the term generally denotes “the law,” or “teachings,” of Buddhism but can also denote, for much Buddhist phenomenology, “momentary elements of consciousness” (which, depending on the branch of Buddhist thought, may or may not have a separate existence of their own). For the sake of this discussion, I would like to use the term’s first Buddhist denotation and explore the ways in which Snyder’s poetics responds to the task of transmitting “Buddhist law/teaching.” In this sense, I will be discussing the didactic aspects of Snyder’s poetry and poetics and will pay especially close attention to how he uses specialized poetic language and devices to convey (or enact) the Zen stereological notion of tathāgatagarbha , or Buddha-dhātu (Buddha matrix or Buddha Nature). Snyder’s desire to transmit this particular dharma is especially compelling, as it requires him to envision a poetics of emptiness that leaves language itself behind.

While Zen Buddhism is famous for its experiential methodologies and its “non-reliance on words and phrases,” poetry, as opposed to discursive prose, has played a central role in this branch of Mahayana Buddhism from its inception. “Zen Poetry,” for Snyder, walks the “edge between what can be said and that which cannot be said.” He continues, “Mantras or koans, or spells are actually superelliptical poems that the reader cannot understand except that he has to put hundreds of more hours of mediation in toward getting it than he has to put in to get the message out of a normal poem.”2 For Snyder, therefore, the work of expressing the dharma entails reaching beyond the normative parameters of language to an extralinguistic experience of the world, which he believes can be accomplished through some forms of poetry. He writes: “There are poets who claim that their poems are made to show the world through the prism of language. Their project is worthy. There is also the work of seeing the world without any prism of language, and to bring that seeing into language. The latter has been the direction of most Chinese and Japanese poetry.”3

Snyder’s vision (by which I mean to underscore the ocularcentric quality of his assertions) of East Asian poetry lies in large measure within Japanese Zen readings of Chinese poetry, which often foreground (and perhaps exaggerate) the difference between discursive, explanatory language available in sutra texts, which wenzi chan (literary Chan) often refer to as “dead words,” 死句, or siju, and the disjunctive, non-discursive language play (or disruption) of classical Chinese poetry, which is referred to as 活句 ( huoju,“live words”). Above all, Zen poetics values Chinese poetry’s use of “live words” for its ability to leave a poetic resonance (that does not function grammatically) conducive to inducing heightened states of awareness.4

One can think of the word play within koan questions as an example of this distinction. Take, for instance, the following well-known koan attributed to Zhaozhou ((趙州, Ja: Jōshū, b. 778–d. 897), “Does a dog possess Buddha Nature?” The ritualized response is “Mu!” “Mu” is the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese character for emptiness 無 (Ch: wu). At first the answer can mean “No,” implying that the respondent does not think a dog has “Buddha Nature.” But the term is also the Japanese onomatopoetic equivalent of a dog bark (Eng: ruff). Upon further introspection, we can see that the dog answers for itself, with a single word, “emptiness,” alone, which implies that dogs possess Buddha Nature for the same reason all things do, by way of their shared unity in emptiness. The language play within the koan sets in motion several interconnected chains of signification, initiated by the word “mu,” thought to disrupt the normal cognitive patterns through which adepts claim to experience states of consciousness beyond “thinking” in any normative sense. (I think of Philip Whalen’s assertion that poetry should, like koans, “wreck the mind.”5)

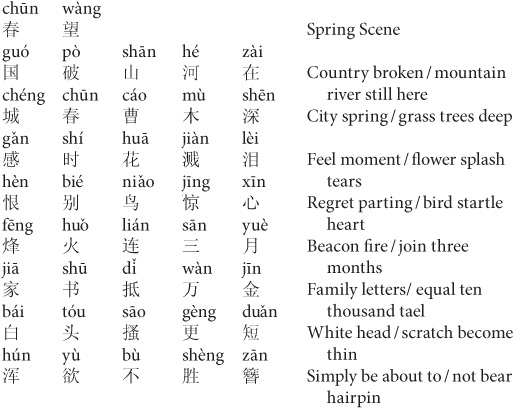

As we saw in the previous chapter, if one pays attention to the correlative patterns of classical Chinese poetic form, one sees the primacy of poetic agency to harmonize with natural patterns of correlation, but read through a Zennist lens, which does not participate in this cosmological economy, the poetic line looks loose, often indeterminate, and open to interpretation. In other words, the classical Chinese poetic line represents “live words.” The Song dynasty poet Wu Ke (d. ca. 1174) brought this Chan/Zen distinction between “live words” and “dead words” (originally linked to koan practice) into poetry when he stated: “Dead poetry is a poetry the language of which is still language; live poetry is a poetry the language of which is no longer language.”6 In his foreword to A Zen Forest , Sayings of the Masters, Soiku Shigematsu’s translation of the Zenrinkushu, Gary Snyder offers a reading of a poem by Du Fu similar to that, which may help illustrate Snyder’s Zennist reading of classical Chinese verse. Snyder cites Du Fu’s famous poem “Spring Scene” as an exemplar of Zen poetics, even though Du Fu was not a Buddhist.

The country is ruined: yet

Mountains and rivers remain.

It’s spring in the walled town,

The grass growing wild.7

Snyder cites Burton Watson’s evaluation of Du Fu’s verse to reveal its use value for Zen practice, which apparently comes from the poem’s “acute sensitivity to the small motions and creatures of nature…. Somewhere in all the ceaseless and seemingly insignificant activities of the natural world, he keeps implying truth is to be found.’ “8 The poet’s turn from the world of human history to the minutia of natural phenomena moves the poem and the reader from the rhythm of society to the ceaseless transience of natural cycles, which are so often neglected by historical grand narratives. We can see that this shift in focus may represent a “live word”9 for Snyder or other Zennist readers, whereby the poem turns the speaker’s or reader’s mind from its normative patterns. Read in this way, Du Fu’s move away from the important historical time of the fall of the Tang capital of Chang An 長安 (today known as Xi An, 西安) to the “other time” of the “grass growing wild” consists of “live words,” which, according to the the Buddhologist Dale Wright, “bespeak the identity or congruence of self and situation,”10 insofar as this focus reminds the reader of the interconnected nature of all phenomena. These lines, in other words, point to interdependence and the permanent presence of transience “directly,” rather than discursively explaining how war, loss, the poet, the reader, and the grass are “one” in emptiness, interconnected. In this sense, Du Fu’s poem was written from a nirvanic perspective, or the perspective of one who is always aware or this “other time” and the interconnected nature of all things in impermanence.

Yet Watson’s and Snyder’s similar readings of Du Fu’s poem interestingly do not presence many of the reasons why this poem, and not another, attained its preeminent position in the Chinese canon. Here is the whole poem:

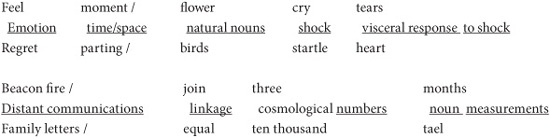

Since Du Fu’s “Spring Scene” is written in the genre of regulated verse (lushi), it conforms to the same tonal patterns, rhyme schemes, and semantic parallelism as the regulated verse discussed in the previous chapter. The success of a poem in this style can be gauged, in part, by the way it naturalizes these formal qualities in a way that leads to an overall unity of content and form. The first couplet can be read as a textbook example of the four-part progression of regulated verse, qi (or to begin, arise), insofar as it sets the time, location, and theme for the rest of the poem. And already we see a correlative interplay of dynamic tension between opposing (but correlatively connected) forces: human culture (country) / nature (mountains and rivers), what is broken / what endures, etc. This poem is particularly well known for its brilliant naturalization of semantic parallelism. As noted earlier, the middle couplets must be parallel, which Du Fu accomplishes with grace and naturalness:

The four couplets move in an orderly progression from the nonparallel, into parallel, and back to the nonparallel, and Zong-Qi Cai writes, “In traditional Chinese poetry criticism, the four couplets are each assigned a specific function: qi (to begin, to arise); cheng (to continue, apt to carry on); zhuan (to make a turn), and he (to close, to enclose).”11 Du Fu’s poem not only perfectly fulfills these functions in each of the couplets, but also ends the poem by returning to temporal progression, which highlights the decay of the poet himself. We can see this last couplet “he” is a return to time and decay, away from the atemporal, parallel stasis of the inner couplets organized by way of vertical symmetry and harmony (as opposed to horizontal syntax, which is temporal, insofar as events take place in time).

Du Fu’s ability not only to conform to the rigors of lushi but also to make these conventions meaningful by revealing the seamlessness of poetic form and content has contributed to the lasting popularity of “Spring View.” Snyder’s and Watson’s readings of the poem, however, arise from a particular context, namely, the way these lines have been anthologized within the Zenrinkushu (A Zen Forest, Sayings of the Masters), a collection of quotes from Chinese and Japanese sources used by Zen practitioners to move beyond conventional thought. The poem’s inclusion in the volume equally reveals a specific, doctrinal reading of Chinese poetry as an “instrument” for enlightenment, which cannot be taken as representative of all Chinese poetry or poetics (which is why I wanted to once again call to mind a correlative reading). This instrumentalist reading of Chinese poetry as a vehicle for teaching the dharma, fa, is further revealed when Snyder argues that “the poets and the Chan masters” of China are “in a sense just the tip of the wave of a deep Chinese sensibility, an attitude toward life and nature that rose and flowed from the seventh to the fourteenth centuries and then slowly waned.”12 Certainly, the “wave” Snyder sees conditioning the “poets and Chan masters” is real, insofar as the particular Chinese practices of Chan/Zen poetry and poetics rise from the greater context of Chinese poetry and sensibilities toward life and nature. Yet it becomes problematic when the base of the wave and its tip are inverted, and Chan/Zennist poetry and poetics are seen as the greater context for Chinese poetry as a whole.13

While Wu Ke’s notion of “live and dead words” is a doctrinal device, the liminality of language suggested in phrases like his was purposefully connected to existing non-Buddhist theories of “poetic resonance” or Chinese poetry’s attenuation of signification, its afterglow, afterimages, lingering tastes, smells, and perhaps most importantly, sounds; in short, a classical Chinese poem has been traditionally valued by some critics for its “resonance,” which is seen to bring language out of its cognitive structures and topographical certainties into the intuitive, suprarational, or what Snyder might call language’s “wilderness.” By the sixth century, Chinese poetics had already formed a wide variety of terms that signal this importance of poetic “resonance.” An inchoate theory of resonance is grounded early on in terms like yiyin (lingering sound), yiwei (lasting flavor), congzhi (double meaning or multivalence).14 But these terms are given a strong sotereological utility in Zen poetics, which one will not find in prior Chinese poetics.

In his poem “The Taste,” Gary Snyder foregrounds the gustatory theory (taste beyond taste) that undergirds ideas of poetic resonance so central to his Zennist notion of Chinese poetry.

I don’t know where it went

Or recall how it worked

What the steps were was it hands?

Or the words and the tune?

All that’s left

is the flavor

that stays.15

Snyder’s poem explores the limits of cognition: when the words have fallen away, when the body has forgotten the proper steps, something intuitive, ready to be, remains; something lingers. Working squarely within the modernist idiom of William Carlos Williams, the pacing and meter of Snyder’s poem is marked by line breaks and grammar rather than by formal prosodic structures. Reminiscent of Williams’s poems like “Nantucket,” the appearance of disjunction within the poem is largely a result of line breaks, not syntax. Written in a more linear fashion replete with conventional punctuation, Snyder’s poem would be only mildly disjunctive, as the poem generally unfolds in a syntactic, discursive way, ending with a marked redundancy that reinforces the poem’s theme of lingering resonances. The poem’s explanatory tone attempts to convey through conventional language (or its “content”) the difficulty of bringing something from the outside (in this case, memory or thought) back inside. Yet, like Pound and other modernists, Snyder is very aware of the resonant quality that English is capable of producing from the grammatical interruption of line breaks. When the syntax is broken by line breaks, we find new potential meanings through enjambment or attenuated moments of indeterminacy. Meanings normally derived from a linear sentence’s momentum can, thus, be redistributed or redirected throughout the poem’s lines or semi-discrete units. Donald Davie writes that “it was only when the line was considered the unit of composition [as opposed to the stanza or sentence as the unit of composition] that there emerged the possibility of ‘breaking’ the line, of disrupting it from within, by throwing weight upon smaller units within the line.”16

The poetic resonance in Snyder’s work is produced by more than his line breaks, however: the resonance arises from the complex relationships between different subunits within a poem. Often Snyder does this by intertextually weaving together different source materials or juxtaposing unadorned visual datum. By exploring Snyder’s use of poetic resonance within poems like “We Wash Our Bowls in This Water,” we can begin to see how such “resonance” or “live words” function as instruments for Snyder to teach a dharma (that proposes an exit from language itself). Let me cite a substantial excerpt from the poem, for a sense of context, before looking at the opening stanza in detail.

We Wash Our Bowls in This Water

“The 1.5 Billion cubic kilometers of water on earth are split by photosynthesis and reconstituted by respiration once every two million years or so.” [Snyder’s italics]

A day on the ragged North Pacific coast get soaked by whipping mist, rainsqualls tumbling, mountain mirror ponds, snowfield slush, rock-wash creeks, earfuls of falls, sworls of ridge-edge snowflakes, swift gravelly rivers, tidewaters crumbly glaciers, high hanging glaciers, shore-side mud pools, icebergs, streams looping through tideflats, spume of brine, distant soft rain drooping

from a cloud,

sea lions lazing under the surface of the sea—

We wash our bowls in this water

It has the flavor of ambrosial dew—

… “Well, lets get going, get back to the rafts”

Swing the big oars,

head into the storm.

We offer it to all daemons and spirits

May all be filled and satisfied.

Om makalu sai svaha!

•

Su Tung-p’o sat out one whole night by a creek on the slopes of Mt. Lu. Next morning he showed this poem to his teacher:

The stream with its sounds is a long broad tongue

The looming mountain is a wide-awake body

Throughout the night song after song

How can I speak at dawn.

Old Master Chang-tsung approved him. Two centuries later Dōgen said,

“Sounds of streams and shapes of mountains.

The sounds never stop and the shapes never cease.

or was it the mountains and streams?

Billions of beings see the morning star

and all become Buddhas!

If you, who are valley streams and looming

mountains,

can’t throw some light on the nature of ridges and rivers,

who can?”17

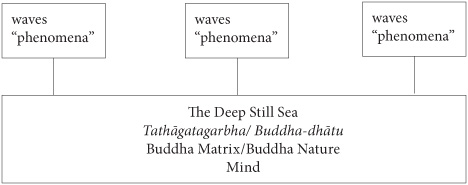

In the first paragraph/stanza, we see a network, or what in Snyder’s often Kegon Buddhist–inflected language might be called a “web,” or “net,” of interrelated phases of the water cycle. Kegon is not a form of Zen, but its central concept of a “net” has had a strong influence on Snyder’s poetics and ecological prose writing. As mentioned in the first chapter, the central teaching of the school holds that all phenomena are interconnected in an infinite web and every point in the web reflects every other point. While Snyder points to this interconnectivity, or what he often refers to as “interbirth,”18 as an ontological foundation for his anti-anthropocentric worldview, I would argue that this concept cannot be equally applied with much success to his notion of Chinese poetics and its role in teaching “the Dharma.” Given the wide proliferation of Buddhist schools and teachings, it is important to locate what “Dharma” Snyder hopes to transmit/teach through his poetry. This stanza, and the poem that follows it, helps us do just this. The fact that each of the images in the opening stanza of the poem represents a different manifestation of the same substance, water, reveals a debt to Yogācāra, and especially the class of teachings associated with the notion of tathāgatagarbha. I would argue that this distinction is central to understanding Snyder’s poetics of emptiness, and by extension a major element of transpacific philosophical, aesthetic, and religious migrations into American poetry more generally.

Like most Buddhist schools, Yogācāra argues that ordinary experience is impermanent in its nature since it depends upon the momentary phenomena of causes and conditions, but it also argues that even though these external objects of perception are empty and devoid of any intrinsic reality (dependently arisen), the states of consciousness that cognize them are real (not dependently arisen). This uncaused “house of consciousness” is called the alaya-vijnana (often translated as “storehouse consciousness”), and in the course of Yogācāran practice a practitioner must cleanse the alaya-vijnana of its contents in order to return to the undivided, uncaused matrix of emptiness, emptied of and, therefore, free from causation. You will notice here a shift in the meaning of “emptiness” itself. In the class of sutras known as Tathāgatagarbha, under which are both the Lankāvatāra Sutra (楞伽經) and the Nirvana Sutra (涅槃經), the truth of emptiness understood as pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination) central to Fenollosa’s Buddhism, shifts to a positive expression of an ontological “Mind” or citta, which is not “empty,” in the sense that it is contingent on causes and conditions (pratītyasamutpāda), but is empty of duality, discrimination, and contingency/change. The Lankāvatāra Sutra19 teaches that this pure “One Mind” can only be experienced after one discards discrimination based on the dualistic (linguistic) intellect. Furthermore, this “positive expression of emptiness” as “Buddha-dhātu” (Buddha Nature, 佛性) or tathāgatagarbha (“embryo/sprout of the Buddha-nature,” 如来蔵) can thus be seen as a shift away from the negative epistemology of Fenollosa’s Buddhism to a positive ontology and soteriology meant to impart a lasting, permanent “true self” in, or more accurately, as tathāgatagarbha.20

To illustrate how this metaphysical structure enters Snyder’s work, let me refer to its most common metaphor once again: water. The Mind is a deep still sea, and thoughts are but waves on its surface. Emptiness, or Buddha Nature, is this same deep, still sea, and all phenomena are but waves on its surface. Phenomena are not real in an ultimate sense since they are not autonomously existent; they are real only insofar as they are generated from Mind/Buddha Nature.

1 “Mind” is the basis for “phenomena”

2 “Mind” gives rise to “phenomena”

3 “Mind” is one, “phenomena” are many

4 “Mind” is real, “phenomena” are not real

5 “Mind” is the essential nature of “phenomena”

6 “Phenomena” are not ultimately real, but have some reality in that they have arisen from the “Mind” and share its nature21

While there is not a consensus on this issue, tathāgatagarbha can be thought of as a “generative monism” or a “positive expression of emptiness”22 and is extended by way of the metaphor of water through the first stanza of Snyder’s poem, insofar as snowflakes, rivers, glaciers, mist, rains, ponds, slush, creeks, falls, pools, icebergs, and clouds are all apparently discrete phenomena but are ultimately manifestations of a single Oneness. Clearly, such a vision of emptiness would find a seat kept warm by Romanticism’s exaltation of idealism, mind, and nature, but it is important to not subsume Yogācāran monism under the umbrella of Romanticism, although one can see why this discourse might be more popular in the United States than non- or anti-monistic concepts of emptiness, such as the Madyamika-inspired notions of emptiness that undergird much of Fenollosa’s poetics or, in a more radical sense, Leslie Scalapino’s writing.23

FIGURE 3.1. Tathāgatagarbha diagram reveals the monistic dimensions of form. Based on diagrams presented in “Critical Buddhism,” in Pruning the Bodhi Tree, 242.

Following the first stanza, we see the italicized lines, which represent quotes from a Zen prayer that would be intoned before mealtime in a Zen monastery:

We wash our bowls in this water

It has the flavor of ambrosial dew—

We find the whole prayer again in an essay by Snyder, entitled “Grace,” in The Practice of the Wild. By inserting decontextualized lines of the prayer throughout the poem (Snyder does not indicate the origin of the lines in the poem), however, Snyder liberates the lines from their natural “communicative” context and sets them afloat within a sea of other semi-discrete units that constitute both the poem’s form and content, further adding to their “resonant” quality. The reader, encountering the lines of the dinner prayer set adrift within the poem, immediately begins making connections between, say, the “this water” (which would ritually refer to an actual bowl of water) of the prayer’s first line and the snowflakes and rivers of the opening stanza. In this way, the discursive prose, like the visual datum of the first stanza, can now be read as “live words,” in the sense that its meanings are no longer predetermined by its original ritual or discursive contexts, but open to multiple levels of signification (which in the Zen poetics of Wu Ke is a feature of “live poetry,” “the language of which is no longer language”). Yet Snyder’s use of parataxis and juxtaposition does not ultimately seek to fragment reality, but aims instead at disrupting normative grammar in order to reveal the Dharma of “unity” in a broader metaphysical sense of an inclusive “Buddha Nature.” Snyder’s poem progresses by floating a discrete series of textual islands individually cut off from their broader discursive bodies and contexts. Here, set adrift within the poem, prayers invoke water, and prose islets written in the imperative tell us to integrate ourselves into this watery unity: “swing the big oars” and “head into the storm.”

The second section of the poem provides us with a map of the intertextual and heterocultural tributaries through which this metaphysics of unity and resonance arise in Snyder’s poetics more generally, for at the center of the Chan/Zen valuation of Chinese poetic resonance lies a single poem by the Song dynasty poet Su Shi (his Buddhist name is Su Dongbo, which I will use here, given the Buddhist context), which we actually encounter in its entirety in the second section of Snyder’s poem.

While not explicitly “about” poetic resonance by itself, Su Dongbo’s poem “赠东林总长老 (“Presented to Master Lin Zongchang”) is rarely “by itself,” but almost always encountered within chan wenzixue, or Zennist, readings of the poem.24 Snyder’s poem mentions the most famous commentary, made by Dogen (Dōgen Zenji, 道元禅師, b. 1200–d. 1253), the founder of the Soto school of Zen, in his essay Keisei Sanshoku谿聲山色 (“Valley Sounds, Mountain Form”).25 In this essay, Dogen writes about how Su Dongpo traveled to Mount Lu to learn about the Buddhist doctrine known as the “inanimate thing teaching” from Master Lin Zongchang.26 Afterward, he traveled back down the mountain and spent the night near a river. It was at this point that the lingering presence of the words of his master mixed with ambient sounds of the water flowing and Su Dongpo received the teaching. Dogen points out that, according to the “inanimate thing teaching,” all things possess Buddha Nature, or are “One” within Buddha Nature, and therefore the teacher’s words are one with the sound of the stream. This realization, enacted in Su Dongpo’s poem, is experiential in a way that the discursive sutra read by the master could not communicate. Su’s poem reads:

溪声便是广长舌

The stream with its sounds is a long broad tongue

Snyder translates the Zen term “universal tongue” as a “long broad tongue,” but in both cases the Chinese term refers to the Buddhist notion of upaya (方便 ) , which itself denotes the infinitely varied ways in which the dharma can be taught so that the hearer can understand.

山色岂非清净身。

The looming mountain is a wide-awake body

This term “wide-awake body” is Snyder’s translation of the Chinese term 净身 (jingshen), which is more literally translated as “purified body,” but in either case refers to the monistic Buddhist concept of an all-encom-passing Buddha Nature (especially when paired with the idea of upaya, for which the concept of tathāgatagarbha is a prominent example). After experiencing his “awakening” during the night, Su experiences a prolific flowing of poetry and song.

夜来八万四千偈

Throughout the night song after song

But in the light of the following day, or in the “clarity” of dead-explanatory language, he cannot express the true nature of his enlightenment.

他日如何举似人。

How can I speak at dawn.

In relation to the doctrinal debate surrounding the question of Buddha Nature and sentience, Su Dongpo’s poem takes a partisan stance, but unlike a sutra that “states” or “explains” using “dead words,” Su’s poem purportedly gives the reader a more direct experience of the universality of Buddha Nature by “showing” that the “valley sounds” are the words/teaching of the dharma, and that the mountain’s form is the pure Buddha Body/Buddha Nature.

Snyder’s poem ends with a quote from Dogen’s essay:

Old Master Chang-tsung approved him. Two centuries later

“Sounds of streams and shapes of mountains.

The sounds never stop and the shapes never cease.

Was it Su who woke or was it the mountains and streams?

Billions of beings see the morning star

and all become Buddhas!

If you, who are valley streams and looming

can’t throw some light on the nature of ridges and rivers,

who can?”27

Dogen’s commentary, like Snyder’s opening stanza, is drawing upon a monistic metaphor of water as a generative Oneness: mountains are like waves on the surface of the water figured as ceaseless impermanence (their sounds, i.e., movement, never cease). The poet, too, is but a manifestation of this water and so should know something of the condition of being mountains as well as water. In this non-differentiated unity, the poet’s enlightenment is not separate from the enlightenment of all other phenomena, since separateness is an illusion. Dogen’s teaching here draws heavily upon a network of water-based Buddhist ideas and terminology that rely on a binary with mountains. Mountains, or 重山 (zhongshan, heavy mountains), offer the illusion of permanence and are often invoked as a metonym for delusion, while water is 流注 (liuzhu, constantly flowing) but in this sense also “ceaseless” 不斷 (buduan, unceasing).

Within this dichotomy, water, often figured as an ocean 海 (hai) (海印, haiyin: the ocean as symbol), takes on a series of positive significations in a wide array of terms. This ocean often signifies an onto-theological monism: 眞如海 ( zhiruhai,“the ocean of the bhūtatathatā, limitlessness”), 淸淨覺海 (qingjiu xueha, “the pure ocean of enlightenment, which underlies the disturbed life of all”), 圓海 (yuanhai, “the all-embracing ocean of Buddhahood”), and 法性海 ( faxinghai,“the ocean of the dharma-nature, vast, unfathomable”). Water is also used to signify enlightened epistemological states, 意水 (yishui, “the mind or will to become calm as still water, on entering samādh”); 淸涼池 (qingliangchi, “the pure lake, or pool, i.e., nirvana”). In Snyder’s poem (and, by extension, Su Dongpo’s poem and Dogen’s essay), water also operates as a soteriological agent which purifies, cleanses, and teaches the dharma directly (as in the vehicle of the “inanimate thing teaching received in/through Su’s poem). Such a function is captured in the phrase 海潮音( haichaoyin,“the ocean-tide [Buddha] voice”), and in terms like 法水 (fashui, “dharma likened to water able to wash away the stains of illusion”), or dharma likened to a 法河 ( fahe,“deep river”), or, finally, 法性水 ( faxingshui,“the water of the dharma-nature, i.e., pure”).28

On multiple occasions Snyder conjures this monistic 法海 ( fahai, dharma ocean). In Earth House Hold, for instance, Snyder writes, “That level of mind—the cool water—not intellect and not—(as Romantics and after have confusingly thought) fantasy—dream world or unconscious. This is just the clear spring—it reflects all things and feeds all things but is of itself transparent.”29 This transparent “dharma ocean” “taught” by Su, Dogen, and Snyder in this poem rushes out to engulf the totality of the poem and all of its differentia, including the reader in what I would like to call Snyder’s retroactive grammar of unifying emptiness. Snyder often chooses to end poems on figures of generative, all-encompassing emptiness that activate a grammar of relationships (that works backward) between the various elements of the poem. The poem “Wave,” for instance, ends a poem filled with differentia that can be recalled into a monistic origin as merely phenomenal “waves” and that lands in the monistic emptiness “of my mind.” The poem “Prayer for the Great Family” ends almost every stanza (filled with differentia) in the refrain, “in our minds so be it.” The poem “Song of the Slip” ends in the expression “make home in the whole,” and in “Kai, Today” Snyder ends with the single word “sea,” and so on.30 These poems might be read as a loose aggregate of indeterminate subunits, if it were not for this retroactive grammar of unifying emptiness.

This is an important distinguishing characteristic of Snyder’s unique use of imagistic parataxis, for as Charles Altieri, following Thomas Parkinson,31 has noted, “this lack of tension is important because it distinguishes Snyder’s lyrics from the expectations created by Modernism. Insofar as his poems are based on dialectic and juxtaposition, Snyder remains traditional, but the lack of tension leads to radically different emotional and philosophical implications.”32 Altieri contrasts Snyder’s “lack of tension” with the unresolvable conflict between particulars in Yeats’s “gyres” or with Eliot’s reliance on a “transcendent still point” to unify particulars,33 and he argues that Snyder “does not require heroic enterprise; reconciliation need not be imposed; it exists in fact.”34 Altieri’s positive reading of Snyder’s poetics arrives in the context of an earlier modernist poetics that is widely condemned for its varied attempts at reconciling difference and determining reading outcomes. Understood through Snyder’s ontology, however, there is no need to unify the world; there is only the soteriological need to help others see that it is always already unified in “Buddha Nature.”

Snyder’s poetics of emptiness, following as it does the Yogācāran monism described earlier, reveals that the differentia of the poem cannot be juxtaposed per se, as they are (from the Yogācāran perspective, or from the perspective of an inclusive “Buddha Nature”) revealed to be of one single emptiness. I am tempted to rewrite Snyder’s or Su Dongpo’s poem to illustrate this point by substituting the character for emptiness for each of the poem’s characters:

空空 空空空

空空 空空空

空空 空空空

空空 空空空35

Taken as a visual field, this conceptual poem might serve to illustrate the absence of juxtaposition (insofar as any differentia in the poem appear as merely other instances of the same thing). However, the poem above cannot escape its own contextual/linguistic nature and would end up undermining the monistic 空 (emptiness) that subsumes Snyder’s and Su’s poems, since the first instance of emptiness that appears in the poem is contextually emptied by every following reiteration. The first emptiness becomes empty of its emptiness, which is further emptied, and the emptiness of this emptiness of emptiness is emptied, etc. Therefore, 空空 would not adequately express Snyder’s poetics of emptiness, since his must transcend language altogether. While “We Wash Our Bowls in This Water” is a compelling poem for its careful blending of imagistic parataxis and intertextual weave, the “emptiness” that governs its articulation would be more adequately signaled by a singular character 空 (like the answer to the koan, we began by asking if dogs have Buddha Nature). It is important to pause and think for a moment about the difference between the emptiness that takes place in language 空空 (or what we might call the emptiness of language) and that which seeks to transcend it through monism, 空

Snyder’s poetics of emptiness, like that of the Yogācāran notion of a non-dual Mind more generally, succeeds by way of overcoming distinctions and even the ontological category of “difference” itself.36 And if we follow the structuralist and poststructuralist view of language, it is even more clear that Snyder would have to transcend or discard language, which is, after all, only a vast system of contingent differences. For Snyder’s poetry to manifest or signal monistic emptiness, it must do away with the contingent relational nature of language, because all linguistic meanings are “caused” or “dependent” upon this contextual condition (part of language’s causal matrix is not, other than the fact that its distinctions and discriminations arise out of (and return to) the monistic emptiness that undergirds all things (Buddha Nature). Unlike language, however, tathāgatagarbha,“Buddha Nature,” is “uncaused” (not subject to the law of pratītyasamutpāda) and therefore cannot be captured in language. This extralinguistic reality, or rigpa, is, therefore, the impossible telos of Snyder’s poetics of emptiness. Yet, in the end, is this not one of the elements of Snyder’s poetics that makes his poetry so compelling? His poetry is offered to us as a “skillful means” (as instruments carefully crafted from highly selective diction and an array of formal devices borrowed from Zennist readings of Chinese poetry and American modernist aesthetics) to help us escape the dualistic confines of language itself.37

It is important to make a clear demarcation between Snyder’s extra-linguistic “vision” of emptiness and Fenollosa’s poetics, which locates emptiness within the causal nexus of language itself (as dependent origination), for Snyder’s poetics of emptiness may have been far more influential than Fenollosa’s (which, again, has not been read in its Buddhist sense). Yet, important Buddhist writing at the end of the twentieth century, like that of Leslie Scalapino, begins where Fenollosa leaves off. In her nonreferential, highly disjunctive poetry, she brings attention to the contingent nature of meaning-making by foregrounding its materiality (the emptiness of signification) and denies the existence of an ontologically stable emptiness “outside” its own, relational “emptiness.” In a lecture entitled “Practitioners of Reality,” given at Stanford University in 2003, she writes:

Words do have referents, but these referents have no substance to them, being themselves merely label entities that depend on other label entities in a giant web where the only reality is the interrelatedness of the entities. There’s no real substratum to this, and the only existence that things can be said to have is a very weak conventional one that is reflected in the pattern of interconnection—that is in the usage of language.38

Again, with strong echoes of Fenollosa’s distinction between conventional completeness and ultimate incompleteness in language (discussed in Chapter 1), Scalapino also combines Hua Yan’s notion of “Indra’s net” with Nāgārjuna’s two truths to articulate a concept of emptiness as contingency: nothing can exist independent of causes and conditions or have nonrelational (and thus autonomous) meaning. In this view, even emptiness is empty of “emptiness” (positive, autonomous presence), as it relies on other, different signifiers, like “fullness” or “completeness,” to derive its meaning (and is thus “caused”). So the word “emptiness” 空 by itself cannot represent ultimate reality, from this view, as it proposes a false sense of ontological stability by hiding its supplements, its relational, contingent nature, 他然 The seemingly insignificant introduction of even one more character, 空空, reveals the dependent nature of meaning-making and subjects “emptiness” to the contingent emptiness of language itself.

At one level the difference between “emptiness” and “empty emptiness” may be thought of as a doctrinal argument (between say Madyamika and Yogācāra39), but it is clear to me that, of the two primary expressions of emptiness (negative and positive), the road Snyder chose to travel would offer less resistance to Romantic and transcendental forms of monistic ontology.40 But this might also be one of the reasons for Snyder’s significant success in integrating Buddhist ideas of emptiness and American Modernism more generally. Nevertheless, the paratactic, largely imagistic form of poems like “We Wash Our Bowls in This Water” draws upon (Zennist readings of) classical Chinese and Japanese poetry, not Romanticism and transcendentalism, to transmit its vision of a monistic “Buddha Nature.” And I believe the interlinguistic foundation of his poetics of emptiness should raise additional questions regarding the status of translation in Snyder’s work.

As we have already discussed, the “compromised” linguistic nature of Su Dongpo’s “enlightenment verse” speaks from an (assumed) enlightened point of view outside the contingency of language through apophatic gestures alone. In a similar apophatic gesture, Han Shan writes:

The pine sings, but there’s no wind.

Who can leap the world’s ties

And sit with me among the white clouds?41

Like Su Dongpo, the enlightened Han Shan is able to hear the non-linguistic teaching of nature: “pine singing without wind.” Yet he is alone in his enlightenment, and he cannot communicate (through the relational nature of language) that which he has experienced beyond it.

They don’t get what I say

& I don’t talk their language.

All I can say to those I meet:

“Try and make it to Cold Mountain”42

For Snyder, and for Zen soteriological readings of Chinese poetry more generally, these poems are not simply apophatic expressions but are communicative insofar as they embody upāya (skillfulness-in-means) capable of helping us reach through language to pull us beyond it. Han Shan is already there. His is a poetry from the other side.

My heart’s not the same as yours.

If your heart was like mine

You’d get it and be right back here.43

Given the apophatic orientation of the nirvanic perspective, the Zen translator encounters not only the limits of language, but the limits of at least two languages.

Given the extralinguistic source of classical Chinese poetry attributed by Snyder’s poetics, it is clear that he will run into a similar problem (or imagine a similar problem, depending on one’s own interpretive frame) as faced by Wai-lim Yip in the next chapter—namely, how does one bring into English an “extralinguistic” experience of emptiness uniquely formulated in a cultural and poetic idiom as distant as classical Chinese poetry? Unlike Yip and Fenollosa, Snyder does not see the uniqueness of Chinese poetry in the Chinese language, or explicitly within a “Chinese worldview,” but in the realized vision of the poets within a shared philosophical and aesthetic tradition. Therefore, Snyder does not foreground the structural disparities between English and Chinese, nor does he see a need to critique translation’s systemic distortion and erasure of what Yip sees as a pre-predicative “Chinese way of seeing.” After all, from the perspective of Tathāgatagarbha doctrine, all such East-West discriminations and dichotomies are less important than (one) Mind that gives rise to them. Instead, Snyder’s discussion of translation tends to foreground the poet’s enlightened vision and explores the ways in which he personally attempts to communicate that vision back into (another) language. In The Real Work, Snyder describes his process of translating Han Shan:

I get the verbal meaning into mind as clearly as I can, but then make an enormous effort of visualization, to “see” what the poem says, non-linguistically, like a movie in your mind, and to feel it. If I can do this (and much of the time the poem eludes this effort) then I write the scene down in English. It is not a translation of the words, it is the same poem in a different language, allowing for the peculiar distortions of my own vision—but keeping it straight as possible.44

Snyder’s translation theory reinforces the purely instrumental notion of language we have already seen (not so dissimilar from the aphoristic notion put forth in the Zhuangzi, of “getting the fish tossing the trap”), which allows him to “see” the signifieds independent of the systems of signification they rely on for their articulation. While Tathāgatagarbha doctrines may not rely as heavily upon vision-centered language as Snyder does,45 it is easy to see how ocular-centric language offers Snyder an appealing set of concepts intuitively consistent with the desire to bypass or discard language.

In a more recent essay, published in the collection The Poem Behind the Poem, Snyder reveals a contemporary continuity with his earlier account of translation:

The translator who wishes to enter the creative territory must make an intellectual and imaginative jump into the mind and world of the poet, and no dictionary will make this easier. In working with the poems of Han-shan, I have several times had a powerful sense of apprehending auras of nonverbal meaning and experiencing the poet’s own mind-of-composition.46

Snyder attributes his ability to “jump into the mind and world of Han Shan” to the purely physical side of the Han Shan world: “the imagery of cold, height, isolation, mountains—is still available to our contemporary experience.” And Snyder has experienced these things for himself, making him “at home in the archetypal land of Han-shan.”47 While it is tempting to attribute Snyder’s visionary translation to his experience in the Sierra Nevadas, to do so would be to miss the metaphysical importance of his translation theory. In The Real Work, Snyder attributes his ability to recall visual details “as vividly as the primary experience” to his practice of Zazen, which reveals special qualifications for translating “extra-linguistic” poetry.48

In his essay “Amazing Grace,” Snyder cites two basic modes of learning, roughly analogous to both Romanticism’s and Zen’s privileging of prepredicative experience over linguistically (culturally) mediated experience: “direct experience” and “hearsay.” Snyder goes on to say: “Nowadays most that we know comes through hearsay—through books, teachers, and television—keyed to only a minimal ground of direct contact with the world.”49 For Snyder, then, one can read about the Sierra Nevadas, see an episode of Nature devoted to it, or hear a lecture on its ecosystems, but these are all secondary to the “direct experience” of unmediated seeing. To “see the world without dualities” would be to behold it without language. And while this idea of “immediate experience” may be, as Bob Perelman notes, a vestige of “anti-theoretical, counter cultural romanticism,”50 it also reflects the broad “Zennist” discourses circulating during the mid-twentieth century. While perhaps tempting, I do not believe we can call this an “anti-theoretical” tendency, just a theoretical position that is heavily critiqued by current poststructuralist (and so-called “critical Buddhist”) discourses. Snyder’s particular application of Zen is in line with his period (and is similar to the positions held by D. T. Suzuki—as well as by innumerable Zen teachers who easily accommodated existing Western values).

Prior to acquiring the tools derived from the theoretical paradigm shifts (the so-called “linguistic turn”) of the last several decades, Zennists commonly spoke of “going straight to things” in an “unmediated experience of the real.”51 Today, with scholars like David Loy, Bernard Faure, Dale Wright, and Donald Lopez, and Zen teachers like Newman Glass, Norman Fischer, as well as the more recent proliferation of Madyamika Buddhist discourses published by scholars like Jeffrey Hopkins and Jay Garfield, Snyder’s poetics, founded during an earlier “wave” of transpacific migrations, may seem outdated but one must remember that Snyder, like everyone else, speaks from within a discrete cultural and historical nexus, and that his Zen studies, with its Yogācāran elements in tow, are not “anti-theoretical” but do offer a theoretical paradigm discordant with contemporary literary criticism (which privileges difference and sees language as a constituent element of all we perceive and know) and should not be exempt from criticism just because of its explicit heterocultural conditions.

It’s a process of tearing yourself out of your personality and culture and putting yourself back in it again.—SNYDER, THE REAL WORK

In Clayton Eshleman’s essay “Imagination’s Body and Comradely Display,” he asserts that “Gary Snyder’s assimilation of Far Eastern religion and culture is the most thorough of any post–World War II American Artist.” Snyder is “a kind of hagazussa [a fence rider or boundary crosser],” Eshleman continues, “who took the Far East as the goal of his flight and, instead of remaining there or becoming an Eastern guru here, has brought his flight information to bear upon our culture and ecology via a resolutely American personality.”52 It would be difficult to argue against Eshleman’s claim that Snyder’s poetry reflects the most sustained and thorough “assimilation of Far Eastern religion and culture” after World War II, if we limit our discussion to Anglo-American poets. Snyder’s study of East Asian languages at the University of California at Berkeley (1952–56); his long-term study of Zen in Japan (1956–68); his extensive travels and social relationships throughout Asia; and his life of “real work” in poetics, ecological activism, and teaching infused with these studies have granted Snyder’s transpacific status a unique “authenticity.” Figured as a hagazussa, Gary Snyder is read by Eshleman as American poetry’s (if not America’s) primary cultural intermediary to Asia. While Ernest Fenollosa spent more time in Japan and arguably had a greater impact on Japanese history, it is Snyder’s, not Fenollosa’s, Buddhism that came to impact American letters in the most direct way.

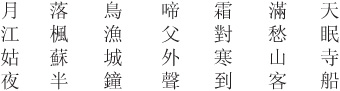

As I have already mentioned, Snyder’s invocation of classical Chinese poetic form authenticates his own poetics of emptiness via Zennist hermeneutics. Snyder’s life story itself is perhaps the most often cited source for the “authenticity” of his work. As is often noted, Snyder’s poetry commonly invokes place, which in the case of his East Asian travels, tends to further Eshleman’s claim for Snyder’s role as “cultural emissary.” For example, in Snyder’s poem “At Maple Bridge,” the intertextual relationship of Snyder’s work to earlier Chinese poems is further “authenticated” because Snyder’s poem is composed (or written as such) at the very spot in China where the Chinese poem Snyder is reworking is set. The original, Chinese poem reads:

“Night Docking Near Maple Bridge”

My translation:

Moon sets crows caw frost filled sky.

River maples fishing lights can’t find sleep

Outside Su Zhou, Cold Mountain Temple

Mid-night bells reach a visitor’s boat

And here is Snyder’s reworking of the poem:

“At Maple Bridge”

Men are mixing gravel and cement

At Maple bridge,

From Cold Mountain temple;

Where Chang Chi heard the bell.

The stones step moorage

Empty, lapping water,

And the bell sound has traveled

Far across the sea.53

The “at” in Snyder’s title immediately reveals Snyder’s proximity to the “real” Maple Bridge where Zhang Ji wrote his famous quatrain. After establishing this proximity, Snyder’s poem, like Zhang’s before him, figures the transmission of emptiness as or through sound. The figuration recalls the story of the Sixth Chan patriarch Hui Ke, told in the Platform Sutra, where Hui Ke becomes enlightened upon hearing the sound of his knife knocking against a stalk of bamboo,54 but this connection between sound and enlightenment can be found in numerous sutras and Chinese poems as well.55

Snyder’s poem starts by situating the reader in modern China, where the sounds of its modernization fill the air around Maple Bridge. He then brings our attention to the “Empty, lapping water,” presumably across which “the bell sound traveled,” to reach Zhang Ji. But when Snyder redirects the bell’s ring through an act of virtual enjambment with the last line, “Far across the sea,” the bell’s reverberation appears to be a thematization of the transpacific pathway whereby Buddhism has traveled to America. The past tense construction of the last line “and the bell sound has traveled,” when combined with the new sounds of industrialization filling the air with its white noise, leads me to believe that rather than simply resonating across the ocean, the bell has, itself, immigrated to a land “far across the sea.” This is a provocative reading that may not reflect the strange paradox of rising commercialism and growing religious activity in China today, but one that reflects instead Snyder’s skepticism toward a rapidly industrializing and modernizing China increasingly known for its embrace of free-market capitalism, harsh treatment of Tibetan Buddhism, and eco-unfriendly policies. Yet it is important to note that China is not a monolith but a nation-state that holds within its boundaries wildly diverse cultural developments and inclinations as capable as the United States is of simultaneous religious fervor and consumerist materialism.

This is of course not the only time Snyder’s poetry takes on a seemingly “righteous” position and may reveal a problem inherent in his poetics’ attempt to overcome difference (through unifying emptiness), as it tends to position the poetic voice inside monistic tathāgatagarbha (Buddha Nature). Such a nirvanic position of enunciation can invest even the slightest innuendo with what I imagine is an unintended degree of authority. This authority is further codified by the inescapable web of reference to his life experiences in Asia and his Buddhist training in his own poetry and poetics, but especially in the hagiographic writing that surrounds him (and the Beat Generation more generally).56 I want to stop short of assigning Snyder the title of cultural hagazussa, however, as such terms still traffic in the currency of what Rey Chow calls an “economy of idealized otherness.”57 Returning to the cross-cultural models discussed in the Prologue, I find the metaphorical language of “fences” to be ill suited for heterocultural literary criticism, given its blunt conceptual limitations. It is my belief that a myopic reading focused on questions of “authenticity or appropriation” “across fences,” while perhaps more applicable to discussions of Snyder’s relationship to Native American cultural texts and practices given its historically specific uniqueness,58 would more likely obfuscate the dynamic, heterocultural nature of Snyder’s transpacific poetics, by reducing important theoretical and aesthetic practices into inert cultural artifacts more suited for adorning the walls of classrooms than for the critical conversations held within or without them. But I hope this chapter has more than adequately demonstrated that Snyder’s transpacific imaginary does constitute, as Eshleman clearly signals in his reading of Snyder, an important and influential example of heterocultural production. Problematic (from the perspective of other schools of Buddhism and contemporary postmodern poetics) yet not illegitimate, influential and generative yet often too narrowly doctrinal and too closely fitted to existing Romantic values (monism), the significance of Snyder’s transformation of classical Chinese poetry into the principal catalyst for an American poetics of emptiness cannot be overstated, yet should not be read uncritically either. He offers his readers a poetry that enacts (as much as it is possible) notions of positive emptiness, which reflect the views of a vast population of Mahayana Buddhists alive today, but his is not the only poetics of emptiness to emerge from the rising and falling mirrors of the Pacific.