Sally go round the moon, Sally,

Sally go round the sun,

Sally go round the omnibus

On a Sunday afternoon.

NURSERY RHYME

I am not certain how it came about that my mother bought the Villa Medici, on the southern slopes of the Fiesole hill above Florence, but I do remember the spring day on which, from the little villa at Rifredi which we had taken for a few months, she took me for a drive up a long hill, first between high walls over which yellow banksia roses tumbled and a tangle of wisteria, then through olive-groves opening to an ever wider view; and finally down a long drive over-shadowed by ilex trees to a terrace with two tall trees—paulownias—which had scattered on the lawn mauve flowers I had never seen before. At the end of the terrace stood a square house with a deep loggia, looking due west towards the sunset over the whole valley of the Arno. There were three rooms papered with Chinese flowers and birds in brilliant colours, with gay tiles upon the floor and upstairs I was shown a little square room with green Florentine furniture, painted with Cupids and garlands of flowers, which, my mother said, would be my own.

“This is where we are going to live.”

Villa Medici

This, then, until my marriage fourteen years later, became my home, and certainly no child could have had a more beautiful one. The house had been built by the great Florentine architect Michelozzo for Cosimo de’ Medici on the foundations of another villa belonging to the Bardi called Belcanto, and it has always seemed strange to me that Cosimo’s grandson Lorenzo should not have kept its original name, for it was in this villa—as in his other house at the foot of the hill at Careggi, the seat of the Platonic Academy—that Tuscan Humanism reached its finest flowering. It was at Careggi that Lorenzo gave a party every year on Plato’s birthday, while Pico della Mirandola and Marsilio Ficino discussed the ‘mysteries of the Ancients’. It was in the Villa Medici at Fiesole that Cristoforo Landino lived for a year, writing his Commentaries on Dante, and that Poliziano composed his long pastoral poem, the Rusticus (before he was sent off, as tutor to the Medici children, to the remote castle of Cafaggiolo in the Mugello, in the dreary company of Lorenzo’s wife, Clarice); and it was at Fiesole that banquets were held by the Medici brothers on spring and summer nights, followed by the reading aloud of poetry, dancing, music and love-making—each with the zest and vigour which Lorenzo brought to all his pursuits—while often the whole company would ride off the next morning at dawn, to hunt in the Mugello. One of these evening parties, however, on the night of April 25, 1478, nearly had a tragic ending, for the bitter rivals of the Medici, the Pazzi, having been invited to a banquet at Fiesole by Lorenzo and his brother Giuliano in honour of Cardinal Riario, planned to take this opportunity of murdering their hosts at their own table. It was only a sudden fit of gout of Giuliano’s that postponed the attack until the following day, when the murderers struck instead in the cathedral of Florence, Giuliano being killed by a dagger-thrust at the foot of the high altar, while Lorenzo barely escaped with his life.

Dutifully showing visitors round the Villa and telling them, like a diligent little parrot, about these events, I used to regret that the more dramatic scene of the conspiracy had not taken place in our own house; and sometimes, when my mother was out of hearing, I made up a story of my own about a daughter of the Medici murdered by her brothers for unfaithfulness to her betrothed, whose corpse had been buried beneath the stairs. Sometimes, I whispered, if my audience seemed sufficiently credulous, her ghost walked the house at night.

The Chinese wallpaper at Villa Medici

The main structure of the house, with its two deep loggias (one of which contained a bust of the last of the Medicean Grand Dukes, Gian Galeazzo), was still the same as it had been in Lorenzo’s time, but in the eighteenth century the house had passed into the hands of Horace Walpole’s sister-in-law, Lady Orford—a lady of dubious reputation but fine taste, to whom we owed the exquisite Chinese wallpapers which were designed especially for some of the drawing-rooms. She, too, held parties at Villa Medici, to which the English Minister in Florence, Sir James Hill, came, and Horace Walpole, and all the fashionable tourists of their day. The house was still in English hands when, in 1911, my mother bought it.

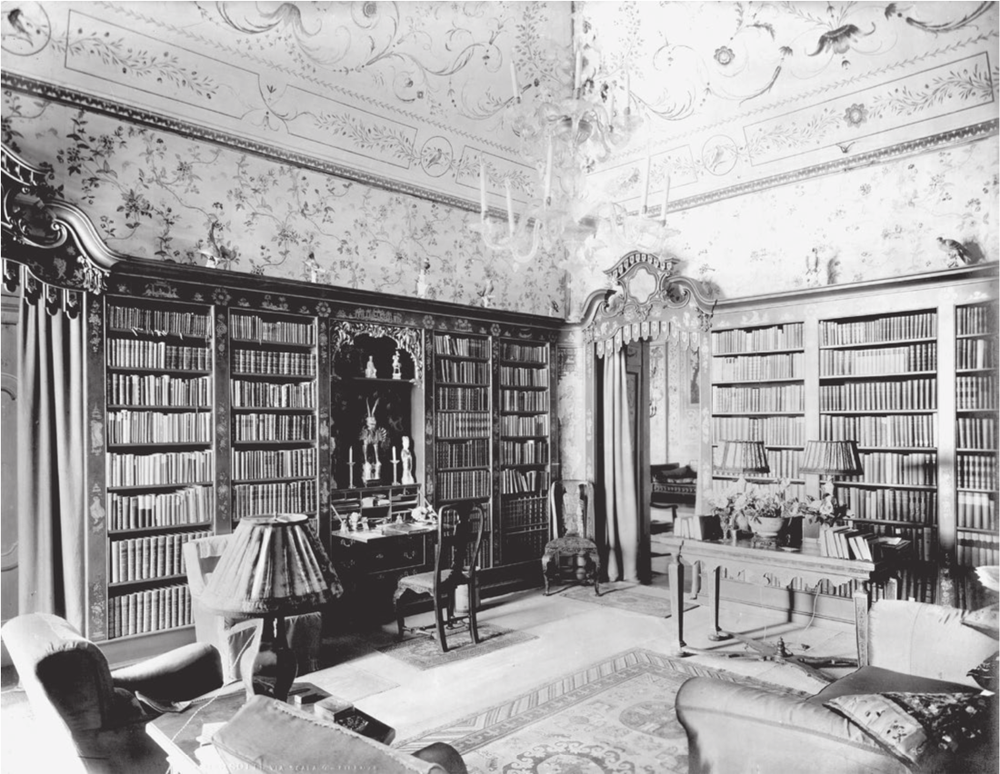

The library at Villa Medici

She restored the Villa’s formal garden to its original design and furnished the house from the Florentine antiquari—at a cost which then seemed high but would now seem moderate—with the help of two gifted young architects, Geoffrey Scott and Cecil Pinsent, who were then working for the famous art critic Bernard Berenson, at his villa at Settignano, I Tatti, and sometimes with the Olympian advice of B.B. himself. What would be the novelty today, I used to wonder, as I came downstairs from the schoolroom for lunch. Sometimes it was a Capodimonte bird to adorn the red lacquer cornice of the library and once a bright-feathered one in a gilded cage, which, when you turned a key, spread its wings and whistled a little melancholy tune; sometimes an inlaid writing-table or a small bronze statue for the fountain; sometimes (f rom Geoffrey) the tale of the latest incident in the Loeser-Berenson feud, or (from Cecil) a map of an unexplored road in the Mugello, leading to a half-deserted villa. No picnic or expedition was complete without Cecil; no luncheon or dinner-party, without Geoffrey’s stories.

For my mother, it must have been a fulfilling and stimulating time but, for my part, I must confess that the immediate effect of being exposed so soon and so intensively to so much art and culture was that I soon came to associate any talk about garden design, Venetian writing-tables, Florentine cassoni or lacquer cabinets, with a tedium which did not fade until, after acquiring a house and garden of my own, I suddenly found that I possessed information which I had consciously rejected, but which had somehow remained with me, like sea-wreck on the shore when the tide has gone out. Though whether this is, or is not, an argument in favour of introducing children early to subjects which still bore them I really do not know.

I have said that I was not consciously aware of the beauty around me; yet I now realise how much more I did take in than I knew, and how much I owe to the space and solitude of those early years. (An understanding of these needs was, I think, the most creative element in the theories of Signora Montessori, who never mistook for sheer naughtiness what she called ‘a child’s defence of its molested life’.) Whenever I was free of my governesses, I escaped into the garden, not to the formal terrace, with its box-edged beds and fountains where my mother took her guests, but to the dark ilex wood above it or the steep terraces of the podere, partly cultivated with plots of wheat or of fragrant beans, partly abandoned to high grass and to the untended bushes of the tangled, half-wild little pink Tuscan roses, perpetually-flowering, le rose d’ogni mese. This became my own domain. The great stone blocks of the Etruscan wall were as good for climbing, with their easy footholds, as were the low-branched olive-trees; the high grass between the rose-bushes was a perfect place in which to lie hidden with a book on a summer’s day, peering down, unseen, at the dwarfed figures of the grown-ups staidly conversing on the terrace far below; and the deep Etruscan well in the midst of the ilex wood, its opening half-concealed by branches and leaves, was dark and dank enough on a winter evening to supply the faint eeriness, faint dread, without which the sunny hillside might have seemed a little tame. It was, I now know, a very small wood, but it was large enough to feel alone in. To dare oneself to venture into its shadows at twilight, to smell the dank rotting leaves and feel one’s feet slipping in the wet earth beside the well, was, for a solitary child, adventure enough. It was not a dread of ‘robbers’ or even of any ghost from the past that overcame one then, but an older, more primitive fear—half pleasurable, wholly absorbing. It is one of the penalties of growing up that these apprehensions and intuitions gradually become blunted. The wall between us and the other world thickens: what was a constant, if unformulated, awareness, becomes just a memory. It is only very rarely, as the years go on, that a trap-door opens in the memory and a whiff of half-forgotten scents, a glimpse of the mysteries, reaches us once again.

The greater part of my childhood, however, was of course not spent in this private world, but on the everyday level of what one was told was real life: meals and lessons, getting up and going to bed, brushing your teeth and saying your prayers. Like other children of my generation, most of my time was spent upstairs, in the nursery or schoolroom. I came down, with my governess, to lunch in the dining-room, and again, when my mother was well enough, to the drawing-room after tea—for an hour of reading aloud, which I have already described. But the rest of my day was spent in a monotonous round of lessons and walks and early schoolroom suppers, and of meals as unvaried as my routine. My mother, having been treated for years for chronic colitis, following the cure of a Swiss specialist, Dr. Combe, decided to forestall any similar tendency in me by also making me follow his strict diet, so that every day, for over two years, the same wholesome, unappetising meal lay before me. I was not a particularly greedy child, but there were days in which the stodgy, unflavoured food simply would not go down, and I can remember the envy with which I would see other children at parties helping themselves to chocolate cake or ice-cream. Visitors to the house, too, made matters worse by commiserating with me, in particular the kind but silly wife of the famous French nerve-specialist, Dr. Vittos, who paid us a visit during that period.

“Pauvre petite,” she would exclaim as she saw my meal, “c’est affreux! C’est une torture!”

I can still feel the facile tears of self-pity rising to my eyes, and hear the dry tones of her husband’s reply:

“Mais non, ma chère, c’est une discipline comme une autre.”

I liked Dr. Vittos, and the plain common sense in his voice was at once convincing. I stopped, once and for all, complaining about my food.

As for company, some little girl chosen by my mother generally came to tea on Sundays, most often a well-behaved, gentle child called Marie-Lou Bourbon del Monte, half-Italian and half-American, whom for many years I considered my ‘best friend’, not because we had much in common, but because she had so sweet a nature that it was impossible not to become fond of her. Later on there was also a very fair, clever English girl, Elnyth Arbuthnot (who later on married, like me, an Italian, a delightful Florentine naval officer, Ferrante Capponi), and a gifted, musical little American girl, Paquita Hagemeyer. Together we formed the nucleus of what we pompously called a ‘Cosmopolitan, Literary, Artistic and Dramatic Society’, the CLADS, which met once a week and published a quarterly magazine. Then there was the weekly excitement of the Saturday dancing-class, the highlight of the week; and the rarer, still greater delight of the few parties to which I was allowed to go at Christmas and Easter. To these occasions I looked forward with an intensity denied to children who had company of their own age every day, though the pitch of my expectations made some disappointment inevitable.

I can still feel myself catching my breath with excitement as, in the crowded little dressing-room of the Florentine palazzo in which Miss Flint’s dancing classes took place, we changed our shoes, smoothed out our accordion-pleated skirts, and then, as the tinny piano struck up, ran to our places. Skipping-ropes, clubs, the five positions, the formal measures of the minuet and gavotte, the valse and the polka, and then—Miss Flint’s speciality—‘expressive dancing’.

“Now, the dance to the Sun-God. Iris, you try it alone today.”

Pride, alarm, ecstasy; rigid with these emotions I twirled, I knelt and raised my hands to heaven, I sank to the ground in worship. At the end came Miss Flint’s verdict: “You’d do very nicely, dear, if you didn’t try so hard.”

At parties, however, I did not try at all, but was content to ‘stand and stare’. They remain in my memory as a brilliant phantasmagoria: the day in Casa Rucellai on which, gently protected by the elder sister Nannina who became my life-long friend, I saw my first children’s play; the annual Christmas party at the Actons’, where the tree and the presents were larger and more expensive than anywhere else, but our young hosts’ most valuable possessions—rare shells from the South Seas and small objets d’art—were locked away in glass cupboards before we arrived; and finally a wonderful fancy-dress dance in our own house, when I was about ten years old, which started at four o’clock for the children and went on until next morning for the grown-ups, and at which Marie-Lou and I, dressed as Renaissance pages, were allowed to stay up until the end, handing round a silver loving-cup.

These parties, glamorous as they were in recollection, took place too seldom for any real friendship to be formed with other children, even if I had known how to make friends. All I did was to look on—quite happily, and entirely unaware that to the other children, who saw me always watched by my governess, restricted to my dull diet, forbidden to come at all if the weather was bad, and often snatched away before the party’s end, my lot seemed a most unenviable one.

Much of their sympathy was misplaced. My childhood at this stage was not unhappy: it was merely disconcerting, in its swift alternations between excitement and tedium, between caviare and bread-and-milk. At the age of twelve, for instance, in the last weeks before the First World War, I was taken for the first time to the theatre in London, to see The Merchant of Venice at the Old Vic. The illusion was so complete that I resented my mother’s faint smile, when, at the words, ‘how far a little candle throws its beams’, a brilliant shaft from the footlights lit up the whole stage. A few days later, I was taken to Covent Garden, to see the Russian Ballet. It was the last year in which Nijinsky was dancing in London: I saw him in Le Spectre de la Rose, and, most unforgettable of all, I saw Pavlova in the Dying Swan. It was then that, for the first time, beauty and delight reached me through my eyes and not through a book. Then we sailed for America and, a few months later, returned to Italy, and I never entered a theatre again (far less a cinema) until I was seventeen.

There was a hardly less vivid contrast at Villa Medici between the social life downstairs, of which I had brief glimpses, and my own schoolroom, in the undiluted company of my governesses—a long and dreary dynasty. Fräulein Hodel, a round cheerful girl, entirely absorbed in the young Italian ragioniere who (to my great interest) played the guitar under her window at night, was perhaps the silliest of these ladies; Mademoiselle Nigg was the most sentimental, Mademoiselle Sanceaux the most neurotic, Mademoiselle Gonnet (who frequently remarked that her neck was considered to resemble the Duchess of Marlborough’s) the vainest. These weaknesses I observed with the cold, unwinking, inhuman eye of childhood. The only governess from whom I learned something of value—a little German and some interest in history and geography—was Fräulein Weibel, a good teacher and an able woman and (I now realise) a very unhappy one, embittered—for she had an illegitimate daughter, whom she called her niece—by caring for another woman’s child instead of her own, grudging me the pretty clothes and the pleasures which she could not give to her own Liselotte. At the time I merely dimly knew that she disliked me for some reason which I could not understand, and considered me in every way inferior to the pig-tailed ‘niece’ whose photograph stood on her bedside table. “Liselotte would never do such a thing,” was the daily refrain. I hated Liselotte.

Two things were harmful to me in the succession of these ladies. The first was that I spent my time in a constant conflict of loyalties (unknown to children today) between the standards of the drawing-room and those of the schoolroom. All of my governesses disliked my mother—partly, I think, from jealousy of her pretty looks and clothes and quick wit, of the agreeable men constantly in and out of the house, and of the general aroma of luxury, and partly because her charming manners to them imperfectly concealed an abysmal indifference. All this was conveyed to me, by sniff and innuendo, as soon as we went upstairs again.

My mother, on the other hand, never spoke to me directly about my governesses, except in terms of respect. “I hope, darling, you do just what Fräulein Weibel tells you”; “I do wish you could have as beautiful a French accent as Mademoiselle Gonnet”; but it would have been a very deaf child who did not overhear the aside, to one of her own friends, after Mademoiselle Nigg left the room, about the Swiss being a sentimental race—and a blind one, who did not observe that never, except to talk about my work, did she spend ten minutes in Fräulein Weibel’s company.

I felt, in short, uncomfortable when governess and parent were in each other’s presence. Moreover, my mentors were also bad for me in a more important way. I was, by nature, not only a law-abiding little girl, but one who needed to respect and admire her elders. When scolded my instinct was never to say to myself, as I have often heard my own children say, “Fräulein’s so cross today”, but rather to feel “How naughty I am!” This instinct, however, was undermined by undeniable facts. Fräulein Weibel was so irritable as to be unfair. Mademoiselle Gonnet flirted with the convalescent British officers who stayed with us after Gallipoli, shaking her chestnut curls and arching her swan-like neck, in a manner both embarrassing and common. I observed all this and despised these ladies—failing, however, to perceive the loneliness beneath Mademoiselle Gonnet’s flirtations and the longing for her own daughter beneath Fräulein Weibel’s crossness. Because I thought Mademoiselle Gonnet silly, I refused to learn, to my lifelong regret, what she could have taught me: correct and fluent French. I became, in short, a supercilious and self-satisfied little prig.

When I was fourteen, however, in the last year of Mademoiselle Gonnet’s reign, I struck. I pointed out to my mother that all the things I wished to learn were being admirably taught by my classical tutor in Florence; that it was her maid who looked after my health and my clothes; and that, if she found it tedious to see my governess’s face at luncheon, I found it still more so to spend all the rest of the day in her company. Might I not in future do without a governess at all? My mother agreed, and thenceforth I lived in my schoolroom in blissful solitude.

There were, however, two persons who brought a very different note into my daily life and whom I dearly loved: my first Italian teacher, Signora Signorini, and, from babyhood, my mother’s maid Kate Leuty, whom I called Doody. Whatever governesses might come and go, Doody was always there. She had been my mother’s maid even before her marriage and had afterwards followed her everywhere—the personification of a devotion and loyalty which never abrogated her right to ‘know her own mind’; the embodiment of stability, kindness, and uncompromising British common sense. Unfailingly dressed in a neat black coat and skirt, her stocky figure stumped behind her mistress over the ranges of the Grand Canyon, through Grecian temples and Eastern bazaars, frequently carrying a small campstool or a hot-water bottle. She sat bolt upright on the low chair supplied for lesser travellers in the prow of Venetian gondolas, gazing expressionlessly across the lagoon; equally upright, and in the same black suit, crowned with a sun-helmet, she rode across the desert on a camel. When asked if she was tired, she would reply, “No, m’lady, we are here for pleasure.”

Ships’ stewards, Swiss concierges, Syrian dragomen, Arab houseboys, Italian housemaids, all instantaneously recognised her authority, and the prestige of the lady whom she served. At her bidding floors were scrubbed, tents were set up, kettles boiled, the necks of chickens were wrung. Again and again I have seen the miracle occur: the arrival at the end of a long day’s motoring at a squalid inn in North Africa or Greece, the unloading of the innumerable suitcases, cloaks and hold-alls with which we travelled, and my mother wandering off with her companions to whichever ruin we had come to see.

“No, don’t bother about the luggage. Leuty will see to things.”

An hour later, when we returned, the metamorphosis had taken place: in my mother’s room the bed was made up with her own sheets and cashmere shawls; the hot-water bottles were already in place and the tea-tray prepared; the engraved bottles and brushes were on the dressing-table; the medicine chest stood open; the guide-books and maps (and perhaps, a pocket copy of The Golden Treasury or La Divina Comedia) were on the bed-table, and the mosquito-net over the bed; an aroma of roast chicken rose from the kitchen and Condy’s Fluid from the bathroom. Another corner of a foreign field was now forever England.

To my mother Leuty awarded the mixture of deference and bluntness of the privileged English ‘upper servant’, gratifying her caprices, while plainly showing that she recognised them as such; but in real illness or grief suddenly gentle as well as efficient. My grandfather fully appreciated her quality and, in one of his letters during the war, wrote to me: ‘You must tell Leuty how grateful we are to her for her care of Mummy, and how we appreciate all she is doing. She is a real and faithful friend to us all and no family ever had a better one. Mind you tell her this for me.’ To me she invariably referred, even long after I was grown-up, as ‘the child’ (“the child needs some more flannel petticoats”; “the child’s looking white; too many parties”), under the impression, apparently, that by avoiding the use of any endearment in speech, she was concealing her complete, but never uncritical, devotion.

In all the changes of homes, of governesses, of plans, in all childish ailments and disappointments, Doody was my ‘fixed mark’. It was she who tucked me into bed every night and later came back to remove the electric torch with which I was reading under the bedclothes. It was she who bought—unthanked—my warm woollen combinations and long black stockings, who taught me to speak the truth and to wash the back of my neck. She was, besides, a most agreeable companion, with a childlike capacity, beneath her placid manner, of enjoying the minor pleasures of travel. I remember, indeed, annoying my mother in Venice, at the age of twelve, by saying (it required some courage) that, rather than look at the Carpaccios with her, I would like to spend the afternoon in walking about the merceria with Doody, buying glass beads and animals, and having an ice at a café. No disapproval was actually expressed, but I started off under a cloud, well knowing that I had shown myself ‘uncultured’.

It was with Doody that, on this and many other occasions, I spent some of the happiest hours of my childhood—secure and at ease, with no obligation to seem either better or cleverer than I really was. She discouraged, indeed, not in words, but by the mere lack of expression on her face, any form of showing off, and, later on, any airs and graces. She understood any real trouble, and wiped out, by her own disregard, any small humiliation. She ordered and put on my Confirmation dress; she inspected and appraised my governesses, my friends, and later on—with some anxiety and mistrust—my young men. Fortunately, she approved of my fiancé, Antonio (in spite of an initial national prejudice), and on my wedding-day it was she who, with an unexpected touch of poetry, wreathed my mirror with the garland of jasmine in which—so her own mother had told her—a bride should first see her face on her wedding morning. And (since my mother was ill) it was the sight of her stout, motionless figure, standing in the loggia, that was my last picture of home, as I drove away for my honeymoon.

When, six years later, a telegram reached me in Venice to tell me that, on a visit to England with my mother, she had been run over by a London bus, I caught the next train to England, but arrived too late. The thought of the hours in which she may have looked in vain for ‘the child’ are still unbearable to me. I realised then that, in all the years of my childhood and youth, I had never thought to say ‘thank you’. This is an attempt—at last—to do so.

The debt that I owe to Signora Signorini is of an entirely different nature, but hardly less great. When she first came to me she was, as I now realise, a young woman, not yet thirty, and she must once have been beautiful, but her looks were already a little faded and her youth dimmed by hard work and resignation. Her life had consisted of fourteen years in a convent-school—reading no book but those the nuns provided, never entering a theatre or a concert-hall—followed by a marriage which, after six happy years, had been obscured by her husband’s dangerous recurring attacks of acute melancholia, which made it necessary for him to be shut away at intervals in a psychiatric hospital, and for her to support her children and herself, by teaching. For five years she came to me for two afternoons a week. I read Pinocchio with her, and then Cuore, and then Le Mie Prigioni; I learned by heart, in conventional slow succession, Rondinella pellegrina and O vaghe montanine pastorelle, and eventually Il cinque maggio. In her quiet, gentle voice she dictated to me the subjects for my essays—on themes intended to develop, rather than the intelligence, the heart: Stasera Pierino è andato a letto contento di aver compiuto una buona azione—Una festa di famiglia—Chi dona ai poveri dona a Dio.1

Sometimes on a Saturday afternoon she brought her children with her—two little girls of much my own age in their best white frocks, carefully pressed and lengthened, both of them much neater and politer than I, both (as I dimly felt) more secure. I envied them, I did not quite know why. I thought it was because they went to school with other children and had their mother to themselves every evening. I think now that what they possessed was the stability of children living in a wholly homogeneous world, one in which there was a constant struggle with genteel poverty and anxiety, but none of the confusion of mind that had come to myself, a child living in a world too sophisticated for it, too varied, too rich. Through the Signorini children, I became acquainted with a world of small, frugal pleasures, long awaited: the gita by tram to Settignano, the new hair-ribbon as a prize for hard work at school, the rare treat of an ice at a café on a Sunday evening, listening to the band, the summer holiday in a small bare villino on the slopes of the Pistoiese hills. I was much surprised to learn that one of their greatest pleasures was coming to play with me at the Villa Medici: I could not think why.

As the years went by and we grew up to different lives, I ceased to see much of the Signorini girls. But my devotion to their mother and her unfailing affection continued until her death a few years ago. It was enough to climb up the steep stairs to the flat, in which she lived with one of her married daughters, and enter the cold, over-furnished sitting-room where she sat in an armchair in the corner—a little old lady now, in a seemly black dress—to feel myself back in the schoolroom again, in a smaller, safer world.

“So Donata [my younger daughter] did well in her exam of terza media? What a consolazione for you, my dear.”

No touch of censoriousness marred her interest in what I had to tell her about my travels and my social life; to her it was all plainly ‘as good as a play’, and equally remote from anything she expected, or even desired, for herself or her daughters. La discrezione, that was her guiding virtue—saper essere discreti. Even when, in her later years, she was often bedridden with bronchitis and painful heart attacks, her demands upon life remained equally moderate. A religious woman, her piety had no touch of mysticism; a loving heart, she loved without demands. “È troppo bello per me!” she would say, stifling her cough, and trying to still her trembling hands, as I brought her a bunch of roses, a pretty dressing-jacket or a pair of fur-lined slippers; and I wish I could convey how genuine the cry was, how far removed from any false humility. She had been brought up and had lived in the true Tuscan tradition, unchanged from the Middle Ages until today—that of ‘the just mean’. Frugality, abstinence and honesty to the point of scruple, deep family affection and a sense of duty, the gentleness of those who ask nothing for themselves, the dignity of self-effacement—these were her attributes, and with them a certain dry shrewdness in her judgements and her comments, which is also peculiarly Tuscan. Kind she was always, but entirely realistic. It was a glimpse of this world and of its attitude to life that I owe to her. It would not be true to say that it has changed the course of my own life or of my behaviour, but its memory has never faded—and sometimes it has made the life of luxury seem a little thin.

Thinness, however, is not the right word to apply to the varied and entertaining world of which echoes floated up the schoolroom stairs at Villa Medici, even in the comparative segregation which (I think rightly) my mother had decreed. Gradually I began to see and hear a little more of what was going on, especially during the visits of my mother’s gay, pretty young English cousin, Irene Lawley, only ten years older than myself. She would stay with us for weeks at a time, bringing with her a breath of carefree enjoyment and fun which I found both intoxicating and upsetting. Wearing a gay and somewhat transparent dressing gown, she came to schoolroom breakfast (much to my governess’s disapproval) and distracted me from my lessons by playing the guitar; she bought one of the Palio banners at Siena and, with some of her young men, practised its complicated furlings on the lawn; she went out riding (while I gaped from the passage window) with a smart young cavalry officer in a blue cloak; she planned moonlight picnics; she produced a children’s play which I had written, and herself took part in what seemed to me an extremely daring comedy about a foreign spy, for the benefit of the Red Cross (this was in 1915). Wherever she went, there was laughter and fun, and also a host of admirers, of whom one, Charles Lister—one of the brilliant young Englishmen who, like Rupert Brooke, lost their lives in the Dardanelles—came to say goodbye to her at Villa Medici. He gave her a pair of lovebirds bought at the Fiesole fair, which eventually were handed on to me, and I regret to say, pecked each other to death.

With Irene came her enchanting mother, Constance, Lady Wenlock—whom I called ‘Aunt Concon’—one of the Edwardian ‘Souls’. The atmosphere that surrounded her, however, had no touch of Edwardian vulgarity, but belonged rather to the eighteenth century: she had the wit of a Madame de Sévigné, the grace of a Madame de Sabran. Incurably romantic, she attracted the confidence of young and old alike, even when in old age she had become so deaf that she had to carry a long ear-trumpet, trimmed with lace to match the colour of her gown; and if one wished to confide a secret to her it was necessary to follow her to a secluded rose-garden. In her clinging pale gowns of fine Indian cashmere, she flitted about the garden like an elegant, frail ghost, as silvery as the olive-trees; dawn and sunset (the only hours that she considered worth portraying in art) found her on a campstool before her easel, enhancing the view at her feet with an imaginary classical column or tempietto, producing water-colour landscapes in which the cypresses were a little blacker and the sunset rather more iridescent than in reality, and in which a few additional towers or spires adorned the distant hillsides. Later on, after my marriage, she came to stay with us in the Val d’Orcia, and would have liked to paint our maremmano oxen, but, since she attributed to them the wildness of the Indian cattle, she dared not trust herself among them. She continued, however, at home and abroad, to rise extremely early, either to paint, or to feed her roses with liquid manure from a little watering-can, curiously incongruous in her delicate hands. “Roses are gross feeders,” she would say, pinning a full-blown Crimson Glory in the soft lace fichu of her dress. Her zest for life, her passion for beauty, was never dimmed by age. On the morning of her death, at the age of eighty, she had risen to paint the dawn.

Sometimes, too, my grandparents came to Villa Medici to visit their daughter—Gran enjoying the house and garden and Gabba the walks and drives in the hills—but both of them a little bored by the constant intellectual and artistic talk, and trying to reassure themselves by repeating, “But of course Sybil always did like this sort of thing!”

They brought England with them—but indeed England was already there. Florentine society at that time was not so much cosmopolitan as made up of singularly disparate elements—an archipelago of little islands that never merged into a continent. The worlds of the various colonies—Russian, French, German, Swiss, American, and English—sometimes overlapped, but seldom fused, and the English colony itself, though the largest and most prosperous, was far from being, in its own eyes, a single unit. “They are, of course,” as E. M. Forster’s clergyman delicately expressed it, “not all equally … some are here for trade, for example.” The real gulf, however, lay not between one kind of resident and another, but between the mere tourist and the established Anglo-Florentine, who felt himself to have become as much a part of the city life as any Tuscan. Some of these residents sank roots so deep that when, at the outbreak of the Second World War, the British Consulate attempted to repatriate them, a number of obscure old ladies firmly refused to leave, saying that, after fifty years’ residence in Florence, they preferred even the risk of a concentration camp to a return to England, where they no longer had any tie or home.

The English church in Via La Marmora, Maquay’s Bank in Via Tornabuoni, Miss Penrose’s school (where their children met all the little Florentines whose parents wished them to acquire fluent English), the Anglo-American Stores in Via Cavour, Vieusseux’s Lending Library and, for the young people, the Tennis Club at the Cascine—these were their focal points. If they lived in a Florentine palazzo it was at once transformed—in spite of its great stone fireplaces and brick or marble floors—into a drawing-room in South Kensington: chintz curtains, framed water-colours, silver rose-bowls and library books, a fragrance of home-made scones and of freshly made tea (“But no Italian will warm the tea-pot properly, my dear”). If they had a villa, though they scrupulously preserved the clipped box and cypress hedges of the formal Italian garden, they yet also introduced a note of home: a Dorothy Perkins rambling among the vines and the wisteria on the pergola, a herbaceous border on the lower terrace, and comfortable wicker chairs upon the lawns. “Bisogna begonia!” (the two words pronounced to rhyme with each other) I heard Mrs. Keppel cry, as, without bending her straight Edwardian back, she firmly prodded her alarmed Tuscan gardener with her long parasol, and then marked with it the precise spots in the beds where she wished the flowers to be planted. The next time we called, the begonias were there—as luxuriant and trim as in the beds of Sandringham.

It was these owners of other villas who were to be seen at my mother’s Sunday tea-parties, but she also ‘got done’, on the same day, such visitors as were passing through Florence. (“The Brackenburys? Oh, we’ll get them done on Sunday.”) The result was a company which seemed odd even to the eyes of a child, but I can set down very little about it. The exceptions are a few people of whom I was genuinely fond: a sweet-natured, blue-eyed young Irishwoman, Nesta de Robeck, who offered to teach me to play the piano and to whom I owe many hours of happiness and a friendship that still endures; my father’s friend, Gordon Gardiner, who would tell me long sagas about his life in the African veldt and the Australian bush, who would read aloud Ticonderoga and laugh at me for getting honey in my hair; and Patience Cockerell, my godmother, who—uncompromisingly dressed in the grey tweed skirt and amber beads which she wore in her Sussex cottage (“I have no money and don’t want to look as if I had”)—spent most of the first years after my father’s death with us, helping to furnish the villa and to plant the garden, but regarding my mother’s new ‘artistic’ friends with a somewhat quizzical eye. “Too clever for us,” she and Gordon agreed—and as it became clear that this, in future, was to be my mother’s world, they both gradually faded from the scene.

Of all the other figures at my mother’s parties, none was three-dimensional for me, though I dutifully handed them the buttered scones, and took them round the garden. I can set down a list of a few of them, but I can’t bring them to life. There was old Lady Paget from Bellosguardo, a rather frightening old lady; there was sometimes Vernon Lee, her grey hair cropped tight above an uncompromising man’s collar and tie, on her way back from a visit to our neighbour Charles Strong, up to whose villa she stumped once a week, to exchange philosophic shouts (for they were both deaf ) on the nature of the Beautiful and the Good. Sometimes the poet Herbert Trench came striding over the hills from Settignano with his lovely daughters—three silent Graces—though he preferred to come alone, to read aloud his lyrics or the long drama that he was writing about Napoleon. Carlo Placci would look in, just back from staying at Duino with Princess von Thurn and Taxis, saying that Rilke, poor fellow, was very ill again, or from Paris, where, he said, Clemenceau had told him … or perhaps (for his range was wide) from Hatfield, where Lord Salisbury … To me, of course, these were only names, but I saw that the grown-ups listened with interest, and thought that this large-nosed old gentleman must be a very important person. But then why did Mr. Berenson laugh, when the stories were repeated to him the next day, and say, “Poor old Placci—no pudding can boil in Europe without his stirring it!”

There was sometimes a small sprinkling, too, of Florentines: the mothers of my friends, correctly dressed for calling, or some more dashing young friends of Irene’s. There were dowdy, distinguished English couples of my grandparents’ generation, who had come up from the Hotel Grande Bretagne or Miss Peters’ pensione to see ‘what sort of place Sybil has settled in’; there were American friends, mostly active, industrious sightseers eager for information, with an occasional representative of ‘Old New York’; and there was also sometimes a contingent from Bloomsbury or Chelsea, critical as well as appreciative. “To think,” Mrs. Masefield exclaimed, as we paced the terrace, “that all this great wall was built by slave labour!” But the tea and the little cakes—which I handed round assiduously—were delicious, the garden was full of flowers, and my mother was the most cordial and expert of hostesses, shepherding her unamalgamable flock into small harmonious groups.

“Iris, will you show Mrs. X and Colonel Y the peonies in the border, while I give Lady Z and Signor Placci some more tea—and Irene, I think Marchese D and Conte R might like to see the view from the West terrace!”

In the end they all went down the hill again, after sunset, feeling that it had been a pleasant afternoon, if slightly disjointed, and my mother sank exhausted on to the sofa, while I thankfully ran upstairs to the schoolroom and my own story-book. I made up my mind, even then, that if I stayed on in Italy after I was grown-up, it would only be to marry an Italian. I did not wish, I thought, to go on belonging to ‘the English colony’.

Of the other ‘interesting’ people in Florence at that time, I have, unfortunately, little to tell. Those whom I now wish I had known—Norman Douglas and Gordon Craig, and later on D. H. Lawrence and the Huxleys—steered clear of villadom. They ate in cheap trattorie, spoke the highly coloured language which the Tuscans called anglo-becero, and disappeared for long intervals into unexplored, exciting regions, of which a few echoes reached us through Geoffrey Scott and Cecil Pinsent. Sometimes I drove over with my mother to Poggio Gherardo—one of the villas to which Boccaccio’s youths and ladies had fled from the great plague in 1348 and in which some of the tales of the Decameron were told—to find old Mrs. Ross reckoning up her olive crop with an eye as shrewd and vigilant as that of any Tuscan farmer, and perhaps sometimes consenting, if in a good mood, to take us into the cosy clutter of her Victorian sitting-room and tell us about how she had once taken ‘a dish of tea’ with the Miss Berrys, and had had a portrait made of her by il Signor (Watts) or had sat on the knee of Meredith, ‘my Poet’. Once or twice, later on, I was allowed to sit in a corner of Charles Loeser’s fine music-room, hung with early Cézannes (for he was one of the first to discover this painter) while the Lener Quartet was playing, and our host’s elf-like little daughter, Matilda, peeped in through the half-open door. Occasionally we visited the most beautiful, and certainly in my eyes the most romantic garden of all, that of the Villa Gamberaia, and I wandered about, hoping that I might catch a glimpse of the place’s owner, Princess Ghika, a famous beauty who, from the day that she had lost her looks, had shut herself up in complete retirement with her English companion, refusing to let anyone see her unveiled face again. Sometimes, I was told, she would come out of the house at dawn to bathe in the pools of the water-garden, or would pace the long cypress avenue at night—but all that I ever saw (and I wonder if a hopeful imagination was not responsible for even this) was a glimpse of a veiled figure at an upper window.

Of the most sharply etched, most celebrated figure of all on the Florentine stage at that time, I also have, at this point, little more to tell. The famous art critic and collector, Bernard Berenson, often came to see my mother, and fairly often, too, I went to I Tatti; but of these visits, my recollections are extremely inhibited. Not that I was not aware that I Tatti was a remarkable place and that I was fortunate to have been invited there. The great, austere library, which seemed to me to contain every book in the world, the terraced gardens sloping down the hill, and the long series of fondi d’oro in every room and passage—all these would have been fascinating, if only I could have been left by myself, uninstructed, to wander alone from one great sad-eyed Madonna to another, making up my own stories about the saints and monks, the beautiful ladies and strange beasts, the translucent landscapes in the background, and the knight riding his white horse up to a castle on the hill. But I was seldom left alone, and even on those rare occasions I was not wholly reassured. For many years I felt the house’s presiding genius to be the first object that one encountered on entering: a great Egyptian cat seated on a trecento cassone in the hall—elegant, inscrutable, irresistibly attractive. It was only when you put out your hand to stroke it, that you discovered it to be made of bronze.

When I went to the children’s parties given by Mrs. Berenson for her grandchildren imaginative plans were made for us: we were bidden to trace the little stream at the foot of the garden, the Mensola, to its source; or to seek for treasure in the music-room. But we stood about unresponsively, beneath the outstretched arms of Sassetta’s St. Francis, mutually suspicious and dumb. In vain did Mrs. Berenson, whose placid Quaker voice and ample frame should surely have been reassuring, urge us to pick up the little flags she had prepared and to prance round the room in a circle, singing.

“If a child performs the gestures of happiness,” I overheard her saying to a grown-up friend, “it becomes happy!”

Whether this would have been true in other circumstances, I cannot say, but certainly it was a very self-conscious group of children who trailed round the room at I Tatti, singing a faint lugubrious chant.

My own personal inhibition was a very simple one: I feared that at any moment Mr. Berenson himself might come in. He had never, in his frequent visits to the Villa Medici, been anything but kind to me; yet I could not feel at ease with him. The exquisiteness of his appearance in his pale grey, perfectly-cut suits, with a dark red carnation in his button-hole, the extreme quietness of his voice, the finish of his manner—these, together with all that I had heard from other people, about his destructive remarks and his encyclopaedic knowledge, were, quite simply, too much for me. When he called upon my mother at tea-time, sometimes bringing with him some of his own guests, perhaps Logan Pearsall Smith or Edith Wharton or Robert Trevelyan, I would wait, hidden at the turn of the stairs, until I heard the car drive away. When he took her out driving in the hills, and sometimes suggested that I should come too, I sat in front beside the chauffeur, only hoping that, when we reached the woods, no more would be asked of me than to unpack the picnic-basket and then slip away with my story-book. Yet on occasions such as these B.B. was a much less alarming figure than the suave host of I Tatti. All affectations cast off, he would leap up the hillside with as much speed and intentness of purpose as if he had still been the young art-student who, in 1888, first gazed upon the Italian scene—his awareness still as fresh as it was then, but enriched and sharpened by every day that had since passed. Whether he took us to see a fading fresco in some remote little country church, or merely stood in the aromatic woods of cypress and pine, looking at the serene outline of a distant hill, or, nearer by, at a happily-placed farm with its dovecot and clump of trees (“Look, a Corot,” he would say, or “a Perugino”); to be with him was to realise, once for all, what was meant by the art of looking. One day, after taking us to see some frescoes, he told the Indian tale of how the God of Bow and Arrow taught his little boy how to hit a mark. “He took him into a wood and asked him what he saw. The boy said, ‘I see a tree.’ ‘Look again’—‘I see a bird’—‘Look again’—‘I see its head’—‘Again’—‘I see its eye’—‘Then shoot!’” It was the same, B.B said, in looking. “One moment is enough, if the concentration is absolute.”

And then, if one asked him a question (though this, of course, was in later years), “Yes,” he would reply, “there are some portraits of Tartar slaves in the fresco by Lorenzetti of The Massacre of Tana in the church of San Francesco in Siena,” or “You will find San Bernardino’s first pulpit, very small and rather worm-eaten, in a little convent-church two miles south of Montalcino.” Or “The best book on that subject is in German, but there is quite a satisfactory minor monograph in Italian—you can come and look at it tomorrow.” For his library, like his mind, was always at the disposal of anyone, however obscure, who really wanted to know.

It is one of my regrets that, in those early years, I did not learn more from him, nor, indeed, derive pleasure from his company. But just as animals reject food which is not fit for them, so children sometimes instinctively draw back from fare for which they are not yet ripe. That complex personality was still, to my dazzled eyes, undecipherable.

What I still find rather difficult to realise, and will perhaps seem incredible to the readers of this chapter, is that the life I have been describing was taking place during the years between 1914 and 1917—in short, during the First World War. But the truth was that in my mother’s ivory tower, as was the case in many other villas inhabited by foreigners on the Florentine hills, the war was only a distant rumble, an inconvenient and unpleasant noise offstage. I do not mean, of course, that there was not a great deal of political talk at my mother’s table, and still more at I Tatti, though much of it in a tone of civilised and superior detachment which to the naïve and unquestioning patriotism of fourteen, seemed very shocking. Sometimes, in the early morning, I would be woken up by the sound of tramping feet and soldiers’ songs and, running down to the terrace below, would see a squad of weary young recruits tramping down the Via Vecchia Fiesolana, and would hear their songs: Addio, mia bella, addio or Bel soldatin, che passi per la via.

Every week a long letter from my grandfather in England—containing, even though I was not yet thirteen when this correspondence began, very much the same comments on recent war news or English politics as he would have written to a friend of his own age—carried me back into a very different mental climate. He deeply regretted—for, in spite of his fair-mindedness and inter national legal experience he had remained very much an old-fashioned Englishman at heart—my being in ‘a foreign country’ at such a time, and was determined to keep me ‘in touch’, a result which he certainly achieved. The letters do not, naturally, contain much that is not now familiar, but it was all new to me: descriptions of London during the black-out, of Zeppelin raids, of relations and friends leaving for the front—and there are also many references to the courage and endurance, after Italy had come in, of the Italian troops on the Carso (‘Napoleon only thought of crossing the Alps, not of fighting there’) as well as frequent injunctions to me to realise the importance of the times in which I was living. ‘Rest assured that there has been nothing, or hardly anything in history, approaching the magnitude of this struggle between vast forces and between right and wrong. On the outcome depends the future of the world, and of that outcome, humanly speaking, you and not we should be the first fruits.’

One of his early letters contained a long description (very uncharacteristic in its show of emotion) of the retreat from Mons of the First British Expeditionary Force, composed entirely of volunteers. ‘Hopelessly outnumbered, without sleep or rest and with the discouragement of ordered retreat, they returned, checked and often defeated by overwhelming forces endeavouring fruitlessly to break their unbreakable line and shake their unbreakable courage. By their tremendous fortitude they gave the unprepared French time to organise their defence, saved Paris and paved the way for the battle of the Marne, upsetting the whole of the German plan, which nearly (how nearly) succeeded. This was about 100,000 men against nearly 800,000. I don’t believe the world has ever seen the like. In this long-drawn-out campaign it is likely to be forgotten, and I want you to remember it and to tell it to your children in after days.’

A childish essay of mine, written in 1916, ‘The World after the War’ (of which my mother must have sent him a copy) pleased him very much. ‘It was very thoughtful and well-written. Sincères felicitations. You ought now to think what the ideal terms of peace should be. If you put that clearly, you will be the only person of my acquaintance who will have done so. I say “ideal” terms, for the ideal is that which in practice is never attained.’ Later on, in 1917, he was writing, ‘Are you not gratified, my little Anglo-American granddaughter, that America is now with us? It may well be the decisive step.’

After Gallipoli, my mother must have felt, in spite of her Florentine friends, a recurrence of her wish in 1914 to ‘do something’, for she wrote to the British Red Cross, offering hospitality in her villa as well as in those of a few English and American friends, to a group of convalescent officers from the Dardanelles. They arrived, in batches of twenty, of whom about eight stayed with my mother and the others were farmed out among her friends, each group staying for about three or four weeks. This enterprise gave great satisfaction to my grandfather. ‘I think,’ he wrote, ‘it is a time you will never forget.’ For me, the prospect of the arrival of these soldiers was the most exciting event of the war, but it soon turned to disappointment. I do not quite know what my expectations were, but certainly nothing less than the arrival of the Argonauts themselves, with Jason at their head, would have fulfilled them. Instead I saw a number of young men in very low spirits, still suffering from dysentery or gastritis, some of them disappointed at having been sent to Italy instead of being invalided home, and all, as time went on, more than a little bored. My mother gave them excellent advice about the right diet for their intestinal troubles and was, as always, a charming and accomplished hostess, but I was already old enough to realise, with some discomfort, that they did not much enjoy her intellectual and artistic friends, but preferred to sit about on the terrace in the sun, flirting mildly with my pretty French governess or my cousin Irene, while the more dashing ones went down to Florence in the evenings, to gayer and smarter parties, where whisky and champagne were available, and some pretty girls. The one thing they did not want to talk about was the war; and not one of them, to my eyes, looked like a hero. After a few months, when the tragic enterprise of the Dardanelles came to an end, they stopped coming, and Villa Medici again became an isolated oasis.

Then, in 1917, came Caporetto, and my first glimpse of reality. One morning my teacher of natural history, Professor Vaccari—a Venetian by birth—was late for his lesson, and when he arrived, looked sad and harassed.

“I can’t stay today,” he said. “I’ve been up all night at the station with the refugees, and I must go back to them at once.”

It was then that he described to me, for the first time, what has since become common knowledge: what happens to a civilian population in times of defeat, and had just happened, that week, in his own Veneto; the evacuation of the villages after Caporetto, the exodus of bewildered country folk with their children and their cumbersome bundles, on roads already filled to overflowing by retreating troops and bombed by the enemy; the confusion and the fear, the old people and children who could not keep up, the stumbling into ditches, falling into rivers—the face of humanity in flight. Since then, we have all been familiar with this scene, if not through our own eyes, in a hundred news-reels; but then, it was new, and the man who described it was talking about his own neighbours at home.

“Can you ask your mother for some blankets,” he said, “and for some warm clothes, boots, food—anything? I’ll borrow a car and come back.”

It was the first time that—since I had helped to pack my parents’ clothes and mine for the Messina earthquake victims—someone had suggested to me that there was something which I might not talk about, but do.

When Vaccari came back I had, with the help of my mother’s car, made the rounds of her friends: the schoolroom was piled high with blankets and clothing.

“I won’t thank you,” Vaccari said briskly, “but if la mamma will allow it, I’ll take you with me.”

An hour later I was with him at the station in Florence, wrapping cold, sleepy children in blankets and helping to hand out cups of coffee and milk from the Red Cross canteen, but most of the time standing bewildered in a corner, uncertain what to do next, watching train after train steam in. The families who poured out—dazed with fatigue and bewilderment—were mostly peasants from the villages along the Piave, the older women swathed in black shawls, the younger ones clutching their children, the old men (for only the old were there) wearing a shuttered, blank look, armoured against incomprehensible misfortune. Huddled on the platform in family groups with their bundles, their one thought was to stay together; all preferred to sleep where they were, rather than to be billeted in different houses. One half-crazed woman, whose child had fallen into the Adige while crossing a crowded bridge, wandered from group to group, tugging the sleeve of anyone who seemed to be in authority.

“Have you seen my Bartolo? He was with me on the bridge.” And then again, peering up into the next face that passed: “Have you seen my Bartolo?”

I went back to Fiesole, and persuaded my mother to let one of the refugee families move into the upper floor of our gardener’s house and, with Doody’s help, bought the necessary furniture, cooking utensils and clothes. After a few months, they were able to go home again, to their own farm near Belluno.

After this, life at the Villa Medici was never quite the same again for me, and during the following autumn, when we were staying in a villa which my mother had taken on the saddle between Capri and Anacapri, I had another enlightening glimpse of real life: the terrible epidemic of Spanish influenza which, in the autumn of 1917, swept across Europe, taking a greater toll of lives than any battle. In Capri, where the little white, flat-roofed houses stood so close together that one could stretch from one roof-top to another, the epidemic spread like the plague in the Middle Ages: there was hardly a house in which there was not a victim. It was then that I saw, at work, a man of whom, until then, I had only thought as one of my mother’s ‘clever’ friends, but a more for-midable one than most, Dr. Axel Munthe. During the summer we had spent a good deal of time with him, sometimes beneath a pillared pergola of his villa at Anacapri, San Michele—‘a strange mixture’ as Compton Mackenzie remarked, ‘of Scandinavian Gothic and Imperial Rome’—and sometimes in the Saracen tower, Materita, in the middle of an olive grove to which he moved, as tourists began to invade the island, for greater seclusion and privacy. Here I heard the sagas that he told my mother about the influence he wielded over kings and queens (and certainly their portraits and souvenirs were there in plenty); the peace that he had brought to dying men in the war, by hypnotising them into unconsciousness of their pain; the bird sanctuary he hoped to form on the island coast, so that the thousands of quail, arriving in spring from their long flight across the Mediterranean, might not sink to a wretched death on the nets smeared with pitch-lime which were prepared for them. Sitting silent in the background, mesmerised by his talk and yet faintly suspicious of it, watching the glance of his blue eyes (so sharp, in spite of the blindness that was already coming over him) I would wonder whether he was really one of the most remarkable men I had ever met, or merely a teller of tales, with a touch of Cagliostro. But during the epidemic, I saw a very different man. Fearless, resourceful, kind, he strode from house to house with unflagging courage and endurance; he saved innumerable lives, and brought comfort, when there was nothing else to bring. It is thus, striding like an ancient, bearded Viking through the narrow streets of Capri, with women stretching out their hands to him in doorways, imploring his help, that I remember him, no longer merely the protagonist of his own legend, but truly the physician and healer.

By then a new phase of my life was beginning, and when, in 1918, my grandfather wrote to me from London about the rejoicings over the Armistice, my one wish was to get to him and to England as soon as possible.

It was during that same summer that, for the first time, I realised that I was no longer a child, but did not yet belong to the grown-up world—a stage familiar to every adolescent, but intensified by my circumstances. This was the summer after Geoffrey Scott’s marriage to my mother, and every week-end, when he came down from the British Embassy in Rome to join us and I would be an unwelcome third in our picnics or evening excursions, I would feel, not jealous, but lonely. Sitting in the prow of the boat, in which we would row out at night to some isolated headland or bay for a picnic, while my mother and Geoffrey talked in low voices in the stern, or after the meal, climbing up over the rocks by myself, I would long, with the passionate rebelliousness and intensity of sixteen, for a life of my own, and friends.

Sometimes, too, other friends of my mother’s came to stay: Algar Thorold, suavely and benignly discoursing on Buddhism and presenting me with a little booklet on The Eightfold Path which I still possess; and Herbert Trench, who would join us on our moonlight picnics, declaiming lyric verses about feminine fragility and masculine chivalry, while I staggered up the rocky path behind him carrying the picnic-basket, or else after dinner reading aloud to us the blank verse of his magniloquent, interminable drama about Napoleon. Recently, opening a volume of Compton Mackenzie’s Memoirs, I was much amused to find this incident recorded there from an observer’s point of view.

“I read the play to Sybil and Iris last night,” said the poet to Compton Mackenzie, “and at the end they were like that.” He made a gesture of admiration and wonder, unable for a moment to find words to express it. It was on this occasion that he went on, his voice lowered into a reverential murmur, “You won’t misunderstand me, my dear fellow, when I say it is genius.”

‘The next day Lady Sybil and Iris were lunching with us at Casa Solitaria. “Oh, my dears,” said Lady Sybil, “Herbert Trench read his Napoleon play to Iris and me yesterday. It went on for hours and at the end of it we were both of us like that”—but the gesture Lady Sybil made was not of admiration and wonder, but of utter exhaustion.’

It was at the Casa Solitaria, the Mackenzies’ enchanting white villa built into the cliff just above the Faraglioni—the rocks on which, according to legend Ulysses heard the Sirens’ song—that to my mind the most exciting, if not always comfortable, evenings of the summer were spent, listening spellbound on the curved terrace above the sea to the stories of our host’s exploits in Greece, while indoors Renata Borgatti was playing Chopin, or the booming voices of two Russian singers, a baritone and a bass whom Mackenzie had nicknamed Bim and Boom, echoed out over the rocks. Compton Mackenzie has written in his Memoirs that he already then foresaw ‘a name in literature for me’. If only he had said so to me then! Both he and his wife Faith were unfailingly kind, but I felt a very stiff, awkward backfisch at their witty, Bohemian parties, and sometimes wished that I were taking part instead (but no-one had asked me) in the gay, unexacting musical entertainment which the boys and girls of my own age were getting up in the little town.

It was in the piazza of Capri, too, that I witnessed my first historical occasion—the proclamation of the Armistice, with all the island bells ringing out, the little square crowded with all the local population and foreign residents, the sindaco in his tri-coloured sash, and Compton Mackenzie in British naval uniform addressing the town councillors in Morgano’s café in a d’Annunziesque speech in Italian in honour of the tricolore, “… rosso col sangue dei combattenti eroi, verde come la terra della nostra Italia irredenta …”

All this took place on November 4, 1918, a week before the proclamation of the Armistice in England. We hastily returned to Florence, to find a letter from my grandfather describing the rejoicings in London and I wrote to him in return that my greatest wish was to get back to him and England as soon as possible.

‘I sympathise with you,’ he wrote. ‘I would not have been away from London then for anything (except direct national service elsewhere), and I do deeply regret that you have missed the national outpouring of heart in the centre of our united Empire … for no rejoicing in a foreign world can move the heart like that among our own people.’ He characteristically added: ‘No generation in history has seen greater days than ours and no-one can I think foresee the problems of the future, whose solution they have rendered necessary. In the midst of rejoicings the nations must pray for sanity’—a prayer which, as we now know, was only partially answered.

In the following spring, I was back again in England with him and Gran and then at Desart, though that visit was inevitably clouded by his deep disappointment over the failure of the Dublin Convention, and his anxiety for the future of Ireland. But the closeness of my bond with my grandparents was renewed and, though after only a few months I returned to my mother in Italy, my childhood at Fiesole was over.

1 ‘Pierino went to bed tonight, happy, because he had done a good deed’—‘A family celebration’—‘A gift to the poor is a gift to God’.