One of the difficulties of the painful process called growing up is the absence of a standard of comparison. How is one to measure the importance of what is happening to one when every event is new? How to judge other people and how to assess oneself? Are one’s emotions shared, in secret, by other girls, or is one, perhaps, unique? Is one’s rebelliousness and discontent a sign of unusual wickedness, or as natural as physical growing-pains?

These questions were sharpened, in any case, by shyness, solitude, and the absence of a stable foundation.

As a little girl, the only religious instruction that I remember was given me at Desart by Gran, whose own faith was that of a cheerful, good and unquestioning child. She told us Bible stories, made us learn the Collect by heart, and said we must pay attention in church to the Lessons and the sermon, so as to be able to say, when we got home, what they had been about. On my visits to America, too, I went regularly to the little church near Westbrook at Great River and could not fail to observe that my American grandmother was a religious woman. I think, however, that (taking, as usual, my examples from books rather than from real life) it was the Evangelical heroines of Charlotte Yonge who inspired me to read a chapter of the Gospels every night at bed-time, and, a little later on, a chapter of The Imitation of Christ or of St. Augustine’s Confessions. I was very reticent about all this, but when, soon after my fourteenth birthday, my mother asked me if I would like to be confirmed, I said that I would. I hoped, I think, for a miracle: complete enlightenment and … wings.

The skin and shell of things

Though fair

Are not thy wish nor prayer

But got by sheer despair

Of wings.

The next few months were very disconcerting. The incumbent of the English Church in Florence was an elderly canon with a large hooked nose—an aristocratic nose, he considered—pompous, rhetorical, and insincere. When he glibly held forth about God and love I was overcome with embarrassment; when he said, sinking his portly form on to the ground beside the schoolroom sofa, “Let us kneel for a few moments in prayer,” and then, rising carefully, dusted the fine black broadcloth of his trousers, I found it difficult not to laugh. Since, however, there was no-one else whom I could ask, I did try to extract from him an answer to some of the questions that were troubling me. They were very simple ones: I wanted, I desperately wanted, to believe in the divinity of Christ; I wanted to reconcile the world as I knew it to the life of faith and prayer; I wanted to be helped to ‘be good’. I received, not a stone, but dust: long, windy dissertations on the Church of England, instructions to learn the Athanasian Creed by heart, an assurance that my besetting sin was pride, explanations with some gusto of the Seventh Commandment, lingering especially on ‘impure thoughts’ (I had no idea what he was talking about) and finally a promise that, on the day of my Confirmation, grace would assuredly be granted me and I would never again suffer from any doubts. Slowly, painfully, I realised that Canon D was just talking. “And is your dear Mother at home?” he would ask, when our ‘little talk’ was over—and I gradually realised, as I took him down to the drawing-room, that it was for this that I had been granted the privilege of a ‘special private preparation’.

Meanwhile the atmosphere at home was not conducive to piety. Geoffrey Scott—an excellent mimic—added to his repertoire a parody of the canon’s drawing-room manner and once, when I had been told to write an essay on ‘The Apostolic Succession in the Church of England’, offered to do it for me, provided I would promise to hand it over without altering a word. My mother confined herself to cutting the parody short: “Really, Geoffrey, not just now!” Another guest gave a comic description of the Bishop of Gibraltar, whose large diocese included Florence. I laughed, of course, downstairs—and afterwards, in my own room, was overcome by a sense of guilt. But I still hoped that, when the actual day came, everything would be different: grace would be granted me.

When the day came, a cold wet Sunday in March, I had a roaring cold in the head. Dressed in my white dress and veil and thinking only of my fear of sneezing at the moment of receiving the Sacrament, I drove down to the ugly little English church in Via della Marmora. There were only three other candidates: two middle-aged women (one of them a housemaid of another English resident) and a curly-haired little boy, who was going in the following term to Dartmouth. His mother, mine, and Doody formed the rest of the congregation. The Bishop, who belonged to the school of muscular Christianity, delivered to us, I presume, the address which had also served him for boys’ schools in Gibraltar and Malta or for crews in the Mediterranean. We were adjured to ‘fight the good fight’ and ‘to play the game’. Behind my veil, shivering, I sneezed and sneezed. I tried in vain to pray. When the great moment came, I tried to hypnotise myself into a state of exaltation; in my heart I knew I was feeling nothing at all.

When we got home, a guest asked, “Well, Iris, do you feel a real Christian now?”

I ran up to my room and burst into tears.

The harm that this episode did me was entirely disproportionate. I had been aware, of course, for some time that many of the people around me were not practising Christians, and that my mother herself only paid lip-service to what she had been taught in her youth out of a sense of seemliness; but it was certainly unfortunate that my first conscious encounter with hypocrisy and snobbishness should have been in a man whom I was prepared to revere as a priest. A simpler or more spontaneously religious child would no doubt have gone on saying her prayers, while looking for other guidance: a more instructed one would hardly have been affected by the canon at all. But there was no-one to guide me. A spring that was just beginning to flow was channelled underground again, for many years.

* * *

Then came the process of ‘coming out’. Self-consciousness and shyness obscured for me the years between seventeen and nineteen and clouded much of my pleasure. I had, indeed, two good reasons for feeling uncertain of myself: the first, that I was introduced in swift succession into the society of three countries in turn—Italy, England, and America—and had to learn to adapt myself to the various shades of correct behaviour in each; and the other, my very clear realisation that I was not pretty. I had as a child, and indeed still retain, a passion for physical beauty, and knew exactly what looks I would like to have—though the image varied at different ages. As a little girl, my ideal was personified by a large family of Russian sisters who lived in a villa near Florence—all as lissom and slim as ballet dancers, with large almond-shaped eyes, long pigtails and dark little heads as glossy as chestnuts. I looked into my glass and saw a spotty round face with a shapeless nose, too big a mouth, soft, mouse-coloured hair—crimped into unbecoming waves by the damp, tight plaits into which it was put every night—and a plump, shapeless figure. A little later the spots disappeared, but my hair remained mouse-coloured and my figure plump. At fifteen, in the full tide of my classical enthusiasm, I would have liked to resemble one of the mourning maidens on an archaic Greek vase, or, in more cheerful moments, Persephone gathering flowers. I bound a gold fillet round my hair but got no closer to my ideal. At seventeen, having heard the French expression jolie laide, I scanned myself anxiously in the glass to see whether I might perhaps be placed in that category. No, I decided, no-one could call me piquante or alluring: I was just plain.

All this was, of course, trivial, but the sense of inferiority engendered was very real—and to this day there is a certain quality of distinction in the looks of some of my friends, a fineness of bone and carriage, which I cannot see without a pang of regret, though a passing one. In youth, however, this preoccupation wasted a lot of time: no form of vanity is more disturbing and persistent than that which is based on insecurity. Any echo of faint praise I snatched and treasured far more eagerly than a pretty child. When, at fifteen, having been made up slightly for the first time to play a very small part in a charity performance at the British Embassy, I overheard Geoffrey say to my mother, “At thirty she may be quite attractive,” I lived in a glow for weeks.

My other cause for anxiety might have been diminished by a little coaching. The first society into which I was introduced was the highly local and traditional one of old-fashioned Florence. The names of the Florentine families whose decorous parties I attended—the Rucellai, Pazzi, Strozzi, Gondi, Ginori, Fresco-baldi, Pandolfini, Guicciardini, Niccolini, Capponi, Ricasoli—had been interwoven into the long tapestry of Florentine history. Some of their houses had been designed by Michelozzo, Alberti or Benedetto da Maiano, or their family chapels frescoed by Ghirlandaio or Filippino Lippi. Their ancestors had been priors under the Comune, merchant princes in the Renaissance, or Liberal country gentlemen in the nineteenth century. For centuries they had ruled and administered their city and cultivated their lands, and some of them were still proud to belong to the great charitable Confraternity of the Misericordia, founded in the thirteenth century to succour the sick and the poor and, anonymous in their cowled hoods, would still pace through the city streets at funerals, bearing lighted torches and intoning prayers. It was, according to tradition, Pazzino de’ Pazzi who, on his return from a Crusade, brought back from the Holy Sepulchre the flint which still sets alight, from the High Altar of the Duomo, the rocket shaped like a dove which, on Holy Saturday, flies down a wire from the altar to a cart decorated with fireworks.1

It was a Capponi who defied the invading troops of Charles VIII of France with the high-sounding phrase, “If you sound your trumpets, we shall toll our bells.” It was a Ricasoli who turned Tuscany into the first truly liberal state, on the English model, on the Continent of Europe.

Their estates, never neglected, like those of many great land-owners of Southern Italy, but frugally and carefully administered under the master’s eye, according to contracts and traditions handed down since the fourteenth century, extended from the rich vineyards of the Chianti to the woods and pastures of the Mugello, from the wheatfields of the Val di Chiana to the wide plains of the Maremma by the sea, where wild buffalo still grazed and there was duck and snipe-shooting in the marshes. Their children were brought up simply and soberly, with strict English nannies and French or German governesses, and spent their long summer holidays, monotonous but untrammelled, on their family estates, varied by perhaps a month at the seaside in a little villino at Forte dei Marmi. And when they grew up (with a few exceptions) they married each other and the story began all over again.

It was into this self-contained, local, dignified society that I—a little foreigner chaperoned by someone else’s mother—was suddenly plunged, as anxious as any chameleon to suit my colour to my surroundings. The standard of formal good manners for a young girl was high: she was required to be modest and self-effacing, but also self-possessed and alert. Moreover I found that my little Italian friends who, a year before, in their dark blue serge frocks and long black stockings, had been just as awkward and as giggly as I, had suddenly blossomed out, without any period of transition, into graceful, charming young women, who seemed to know by instinct what, on every occasion, they should do and say. I observed, for instance, that they gracefully made their way across the room at a party, asking to be introduced when a married woman came in whom they did not know (with a slight curtsy, if she was an old lady); they would even stop dancing to do this, make their polite greetings, and return unperturbed to their partner. But how could such ease of manner be achieved? Sometimes I pretended blindness when one of these ladies appeared; sometimes, out of an excess of zeal, I asked to be introduced to one whom I already knew, who merely smiled benevolently, saying, “But cara, I am Fiammetta’s grandmother”; often I stumbled over their feet. (These ladies sat in a formidable row, on chairs of golden or crimson damask, at one end of the room, watching the young people dance.) But the worst occasion was the one on which, in Casa Niccolini, having shyly made my farewells to my hostess in an interval at a tea-dance, I turned and made for the door in such a hurry that—having forgotten how well the floor was polished—I slipped and fell down, but continued to skid at full speed across the ballroom, with such impetus that I was hurled through the door on to the landing outside. As the door swung back a shout of laughter followed me—or did I simply imagine it? I took to my heels and ran down the wide marble staircase. Never, never, I swore to myself, would I go back again!

The only dance that I remember with unalloyed pleasure—since for once I did not fear a lack of partners—was my own, which my mother gave for me at Villa Medici on a moonlit night in June. For the first time I had a ball-dress from a real couturier, with full skirts of varying shades of blue tulle and silver shoes, and my hair was properly done. For a moment, as Doody fastened my dress and I saw my excited face and shining eyes in the glass, I thought, with an exultation surely denied to any recognised beauty, “I really believe I am almost pretty!” The terrace, where supper was laid on little tables, was lit with Japanese lanterns; the fireflies darted among the wheat in the podere below; the air was heavy with jasmine and roses, and at midnight fireworks from the West terrace soared like jewelled fountains between us and the valley. It was the night which every young girl dreams of having once in her life—Natasha’s first ball—and perhaps all the more glamorous because I was still heart-free and ready to see my Prince André in every partner in turn.

My first English party was a very different matter. It was a week-end at Lord Ilchester’s country house Melbury, in Dorset, for a hunt-ball, to which I had been invited because the daughter of the house, Mary Fox-Strangways, had been asked up to Villa Medici the summer before, when she was studying Italian in Florence. Though life has certainly often made me more unhappy, I do not think it has ever given me three days of more unrelieved discomfort. I arrived knowing no-one but Mary—and her only slightly—one day later than the rest of the house-party, when the other guests had already made friends, and was led by my kind but somewhat overwhelming hostess into a drawing-room in which a lot of strange young people were sitting at a round table, playing Animal Grab. Thankful to sink into anonymity, I chose the mouse as my animal and contributed only a few small squeaks. But when, at the game’s end, Mary took me upstairs and through a labyrinth of passages to my cold, Victorian bedroom to dress for dinner, and I had to put on the hideous satin dress of electric blue with spangles (suitable for a circus-rider of fifty) which I had injudiciously bought for myself in a small shop near Hanover Square, my first problem arose: how could I find my way downstairs again? In the far distance a gong was booming, but run as I might in my tight high-heeled slippers down one passage after another, none brought me to any stairs. Breathless and dishevelled, I at last returned to my own room, where Mary had been sent to fetch me. “Let’s be quick, Papa’s waiting,” was all she said; but, as we entered the drawing-room, the whole party was already assembled. I knew that I had begun badly.

The ball itself was not—not quite—as bad as I had feared. There was a disconcerting moment before starting when Mary, charmingly and suitably dressed in white tulle and gardenias and watched by an adoring group of nannies, nursery maids, and house-maids, came down the grand staircase (for it was her first ball) followed by a galaxy of her friends in equally suitable dresses in varying shades of pale blue, yellow, and rose tulle, which I compared with my middle-aged satin.

“How … how gay you look, my dear child!” said my kind hostess—but I was not deceived.

When, however, we actually reached the ball, the crowd was so great, the scene so novel, that my self-consciousness subsided. All the way in the car I had been absorbed in silent prayer that someone, anyone, would take me in to supper. But almost as soon as we arrived, a tall, fair young guardsman, who had sat next to me at dinner and had told me that he was in my cousin Gerald’s regiment, came up and asked me to supper. Has Lady Ilchester told him to do so, or Gerald? I wondered, too deeply grateful for any pride. With my chief anxiety set at rest, I was even able to enjoy the amusing spectacle: the good-looking men, in their pink coats; the hearty, self-assured girls; the general sense of being at a great family party, which increased with Sir Roger de Coverley and the wild gallop at the end. Almost all the young men of our party danced with me and I came home flushed with relief and pleasure, feeling that I was, perhaps, just like other girls after all.

The next day, however, dispelled this belief. No-one had told me that one cannot go to an English country house without a tweed coat and skirt and sensible country shoes, and when I came downstairs in the rather shiny dark blue serge, which was left over from my schoolgirl wardrobe, and black town shoes, I felt like a pekinese in a pack of hounds—only treated with indulgence, because so manifestly belonging to a different species.

“Do let me lend you my brogues,” urged Mary with transparent tact, “as you’ve forgotten yours.”

I miserably thanked her and, since they were a size too large, returned from our walk across the turnip-fields with a blister on my heel.

There was a reprieve when my host kindly took half-an-hour in his busy day to show his youngest and most awkward guest the books and treasures of Melbury: in his library and looking at his fine pictures, I was once again in a familiar world. But the only really happy moment of my visit was when, on Monday morning, I climbed into the train that was to take me away.

My first London season, in the following summer, is very vague in my memory—except for the leitmotif of anxiety. My mother reluctantly but dutifully had borrowed from Aunt Constance her charming house in Portland Place, and here we gave a series of dreary little dinner parties, mostly attended by very pink and tongue-tied young men whom I had never seen before and whose only claim to be there was that they, too, had been invited to the same ball. One of them, however, a good-looking, red-haired young man in the Guards,—considered much too ‘artistic’ by his brother officers—seemed to me delightfully unconventional because, instead of asking me to tea at Gunther’s, he took me for a bus-ride to the City to see the Wren churches, and it was a great pleasure to find him again, looking very grand in his dress uniform, at the Buckingham Palace Ball. Like Catherine Morland, I felt that I had ‘some acquaintance in Bath’.

Indeed I enjoyed the Court Ball immensely: my conventional long white dress with its train, my absurd headdress with feathers, the snobbish satisfaction of having the privilege of the ‘entrée’ (because my aunt was then lady-in-waiting), the gaping crowds as we got out of the car, the fine uniforms, the fender-like tiaras of the dowagers and the jewelled turbans of the Indian Princes. And I enjoyed some of the other balls, too—beforehand, if not while they were going on—since an incorrigible strain of hopefulness still whispered before each occasion that tonight would surely be different: tonight would be the night!

I got a good deal of pleasure, too, from several other ‘features’ of the Season: the Trooping the Colour, which we saw from the rooms of a friend of my grandfather’s at the Admiralty, with my cousin Gerald suddenly transformed into a symbolic figure, since he happened to be one of the young officers taking part; and also days at Hurlingham, Lords, and Henley—all the occasions, in short, at which I could be a mere spectator. I was even able to hypnotise myself, as I walked round and round Lords in my best pale blue dress with some Etonian friend of my cousin’s, or climbed on to one of the coaches for lunch, into not realising how very dull the young men really were, how little I cared about cricket, and how positively glutted I felt with strawberries and cream. Only sometimes a stifled inner voice would whisper, “This is called pleasure, but I am not enjoying myself!”

If this description, however, has left the impression that I was already blasé, it has been very misleading. During the long years of the War in Italy I had fallen in love with England—or rather with my idea of England, based chiefly upon my grand-father’s letters, my mother’s conversation, and a fine medley of the books I had read—from Six to Sixteen to The Most Popular Girl in the Fifth and, at a later stage, from Jane Austen to Rose Macaulay, from St. Agnes’ Eve to The Shropshire Lad. The world I had built up in my imagination was unlike any country upon land or sea. It was a phantasmagoria of Queen Anne country houses and Oxford colleges and libraries, of village cricket and nursery tea, of hollyhocks in cottage gardens and cathedral spires; of friends, friends, friends with whom I could be at ease, and of a deep swift stream perpetually gliding between green banks, while a young man (his contours still somewhat blurred) read poetry aloud to me. And whenever the real England offered me anything that faintly corresponded to these dreams, I fell in love with it all over again.

I fell in love with Eton on my first Fourth of June—wholly entranced by the beauty of the buildings, of the playing-fields and of the boys’ voices at Evensong in College Chapel. I determined to marry an Englishman so as to be able to send my sons to Eton—but unfortunately no candidates were forthcoming.

I spent a long week-end in Rutland with the family of the young man who had taken me to see the Wren churches, and for three days I believed that this was the existence that, for the rest of my life, I would like to lead. I attended the prize-giving of Uppingham School (with my host, a distinguished old General, giving the prizes) and handed out the lemonade at the tennis party; I helped my hostess to cut off the dead heads in the herbaceous border and to ‘do the flowers’ for the dinner-table. I got up very early one morning to pick mushrooms with John before breakfast in the green, lush meadows in the valley, while the grass was still glittering with dew; and, on another day, we bicycled across half the county to rub the brasses of some eighteenth-century tombs in another village. I fell in love with the whole setting: with the little Norman church of grey stone, in which some of my host’s ancestors lay with a Crusader’s Cross upon their breasts, and the General read the Lesson, as my grandfather had done at Desart (though not so well). I fell in love with my chintz-covered bedroom and its view of gentle meadow land and farm land, with the humming of bees and the scent of mignonette, and perhaps even with my elderly hosts—as rooted, immovable and right in their setting as the grey stones of their church. But I had enough sense to realise that I was not—just not—in love with their charming son, and above all, that he did not care for me. We parted good friends, though I shed a tear or two in the train back to London, not so much for him as for an England to which, I instinctively knew, I would never belong. What I did not, of course, then realise was that, by the time I reached middle-age, that particular England would have ceased to exist.

It was from this society that, after only a short interval at Villa Medici, I sailed in the autumn of 1920 to go through the debutante hoops in yet another setting; that of New York. For four years, during the whole of the war, I had been cut off from my American relations. I had, indeed, been back to see my American grandmother the year before, when I was just seventeen, but this had been merely a short visit, and though it had sufficed to reawaken my affection for her and for Westbrook, it had also made me aware of the rift between her and my mother, which had begun with the latter’s decision to bring me up in Italy and had been increased by her determination to return to England as soon as the war was declared in 1914.

I therefore set off for my American debut alone, or rather in the company of the sweet young Irish maid, only a few years older than myself, Alice Walsh, whose life has been intertwined with mine for much of the rest of my life. On the voyage I already felt torn between divided loyalties, and they were put to the test as soon as my trunk was unpacked. After one glance at the clothes it contained—the sage-green woollen dress from Woollands, the silver brocade evening-dress made out of an Egyptian shawl, the hand-embroidered but ill-cut linen dress from the Via della Vigna Nuova—my grandmother, who was herself the personification of chic and good taste, swept me off to Bendel’s for a complete outfit. Never had I seen such lovely clothes before! There was a deep rose-coloured taffeta evening dress with a long, wide-panelled skirt from Lanvin, like a Nattier painting, which, fifty years later, I can still remember and in which, I felt, even I would be confident. But was it fair to my mother to accept so many gifts, which not only replaced, but plainly by implication condemned, the clothes she had bought for me? My solution was not a graceful one: I wore the fine clothes, but (at least in my grandmother’s presence) grudgingly and scarcely saying thank you.

The process of becoming a debutante in New York in 1920 was a truly formidable one. Even for girls who had grown up together at the same nursery parties, dancing schools and pre-debutante dances, and whose brothers and cousins had also been through a similar mill, the pace was grilling, and for a newcomer like myself the whole routine was misery. The social day would start with a large debutantes’ lunch, entirely feminine, at which—dressed in our best silk or velvet dresses—twenty or thirty of us would be given an elaborate meal, the talk consisting almost entirely of gossip and shrieks of laughter about people I did not know, or competitive talk about dances and partners. A stranger like myself could do little but crumble her bread and eat. Then came a concert or matinee, and, as the evening approached, a new anxiety: would a white cardboard box be lying on one’s dressing table and would it be from the right young man? To have a ‘corsage’ (generally consisting of orchids or gardenias and costing far more than the giver could afford) was a sign of success; or rather, not to have one, was so certain a sign of failure, not only in the eyes of one’s friends but of one’s family, that I was told it was not unusual for an unpopular girl surreptitiously to send one to herself! If two boxes came on the same day, there was the problem of what to say later on, to the donor whose gift one did not wear—but this was a dilemma that seldom offered itself to me. Then came a large dinner-party, at which I was able to obtain an immediate if fleeting popularity by dividing my oysters between my two neighbours, and then, two or three balls in succession.

It was then that the real competition began. The ‘cutting-in’ system seemed to have been especially devised to ensure that a popular girl should increase her popularity, while a ‘pill’ would be progressively deprived of hope. The men all stood in the ‘stag-line’ at one end of the room, watching, and one of them would ‘cut in’ on any girl by tapping her partner on the shoulder. A popular girl would thus often only dance a few steps before she was ‘cut in’ on again; but a girl who was plain, danced badly, or merely happened to have few acquaintances, would slowly proceed round and round the room with her partner, mercilessly linked together like two figures in Dante’s Inferno. The longer her plight lasted, the less likely it was that she would be freed; for it would take a very polite young man or a very faithful old friend to risk being ‘stuck’ with her for the rest of the evening.

In addition, this was one of the Prohibition years. This did not mean that there was no drinking, but merely that the young ‘college boys’ who were our partners, instead of having learned to drink wine or good whisky in moderation at their parents’ table, now drank, from tepid hip-flasks in their cloak-room, liquor which was often sheer poison and of which a very small amount went straight to their heads. To have upon the stag-line a close friend to whom you could signal for help, if your partner was too obviously overcome or amorous, became extremely useful.

Here, as in London, it was the most formal entertainments that I enjoyed most, since I was then again able to become merely a spectator. My grandfather had been one of the first box-holders at the Metropolitan, and I still remember the glitter of jewels and the exquisite dresses on a gala night, as well as the galaxy of great singers whom I then heard for the first time. Every week, before this occasion, the same social crisis arose. “Have we got any men yet, for Thursday evening?” Music-loving and leisured men who wished to sit through a whole opera were scarce, and were apt to be booked for weeks beforehand by box-holding hostesses; young men of this kind were still scarcer, so that I usually sat (to my secret relief ) in the front of the box, bolt upright in my best dress and long white gloves, between my grandmother and another lady of her age, attended by two kindly, musical old gentlemen, and felt free to listen to the music in peace. It was thus that I heard Jeritza as Elsa, on the night of her debut in New York, and later on in the Walküre; Caruso in Pagliacci, on the gala night on which King Albert of Belgium was welcomed to New York in a frenzy of enthusiasm directly after the First World War, and Lucrezia Bori in Kovancina; and I was present, too, on the first night after the war, on which Chaliapin returned in the part of Boris Godunov to his adoring public. When, at the end of the performance, he came back to receive his applause and, tearing off his royal cloak and robes, stood in the blouse of a Russian peasant, the Russians in the audience, in a state of delirium, climbed up over the footlights and carried him off the stage; and when, a few minutes later, I was taken behind the scenes by a friend of his, it was to witness a charming scene: the comparatively tiny Lucrezia Bori, unable to reach up to embrace the giant properly, being lifted up by him on to a table, from which she could comfortably throw her arms around his neck.

Looking back on those three years, I am inclined to think that they were a considerable waste of time, for although it is perhaps necessary to learn something of the ways of the world sooner or later, I think I would have been both happier and nicer—because not constricted into a mould which was not my natural one—if I had been allowed to go instead, as I wished, to Oxford. There, working at the subjects I cared about and learning many things which I was later on obliged to acquire without assistance, I would have found my own level. As a debutante in London and New York I was constantly aware of values which I did not share, and yet was not brave enough (or perhaps merely too young) to disregard, and spent my time in striving for prizes I did not really care to win. To prove to myself, as well as to others, that I too could have some beaux, I encouraged young men whom I did not really like very much, and was then both surprised and distressed when they fell in love with me. For fear of being thought a blue-stocking or a prig, I learned to refrain from talking about the things that really interested me, but was extremely bad at talking about anything else. All this was not only a waste of time and energy: just as there are some books which are, in Salvemini’s phrase, ‘libri fecondatori’, from which new ideas are born, so there are some periods of one’s life which hold in them the seeds of growth, and some that do not. In those years I was deflected—by vanity, preoccupation, and lack of self-confidence—from my natural course. I was a less complete person, that is less completely myself, than the unfledged schoolgirl who had read Virgil with Monti.

In the interval, however, I was, in spite of these obstacles, growing up. I began to fall in love, rather often and rather intensely, but was not very clear about what was happening to me, since, in spite of all my precocious reading, I was quite unable to apply what I had found in books to any useful purpose in ‘real life’. And then some young men actually fell in love with me. I have sometimes wondered whether any of them realised how much gratitude, as well as ignorance, there was in my response. The one of these young men who surprised me most, and whom I met for the first time when I was still a plumpish schoolgirl of not yet eighteen and he a young man of twenty-eight, tall, dark and reserved, and possessed of more than his fair share of charm—chaperoning his younger sister at a small dance—was my future husband, Antonio Origo. It seemed to me so odd as to be almost incredible that he not only danced with me, but appeared to enjoy talking to me afterwards, and when, a month later, he sent me a picture-postcard of friendly, if formal, greetings, it provided enough food for a whole summer’s daydreams. It was not, however, until two years later that we met again—under very different circumstances, since his father was then dying of cancer and he was nursing him devotedly. After long nights at his father’s bedside, he would sometimes walk up the Fiesole hill in the early morning, and we might have a few minutes together, and sometimes, too, we would steal brief walks on country paths where we hoped we would meet no-one we knew. (We did, of course, meet a friend of my mother’s one day, but she had the kindness to remain silent.) It was then that we ‘reached an understanding’, which was sealed by a further meeting in Venice in the autumn, but my mother (who had extracted a promise from me some time before not to become engaged until I was twenty-one) now insisted on a total separation of six months—although she could offer no serious objections except that Antonio was indubitably Italian and a Catholic, and also, she said, too good-looking and too grown-up for me. We kept our promise scrupulously—the only infringement being a little crystal casket of lilies-of-the-valley which Antonio sent me (without a card) on Christmas Day, and which my mother promptly took to her own room, since she still found it inconceivable that anyone should send flowers to me. But on the day when the six months came to an end, a letter was waiting for me, and in the following summer Antonio went briefly to England to meet my English grandparents and then to join me at Westbrook, where our engagement was at last announced.

In deciding to marry Antonio I was not only making—although deeply in love—the personal choice involved in every marriage. I was deliberately choosing life in Italy, rather than in England or America, and, though ignorant of much that I was undertaking, was determined to mould myself to the way of life that my fiancé and I had chosen. Both of us were suffering from a strong reaction against the kind of life for which our parents had prepared us: I against the over-sophisticated, over-intellectual society which had been the background of my youth; Antonio against the world of business for which his education had fitted him, and which was incongruous, not only to his nature and taste, but to the atmosphere he had known in his father’s house. Marchese Clemente Origo—Roman by birth, with a Russian mother, Paolina Polyectoff—had cut a brilliant figure in his youth as a smart cavalry officer in the Genova Cavalleria, a man as tall and gaunt as Don Quixote and with something of the same panache. He bought his horses in Dublin and sent his fine shirts to be laundered in London, but devoted the second half of his life to the arts, becoming a well-known painter and sculptor. He divided the year between Florence and a small house on what was then a wild, lonely stretch of beach and pine-forest at Motrone, on the Versilian coast, with frequent visits to Paris and Venice, to Bayreuth and Munich—wherever, in short, good art, amusing talk and pretty women were to be found. His wife, Rosa Tarsis (previously married to Duke Pompeo Litta), possessed a singularly sweet nature and a charming voice, and their house soon became a centre for many outstanding musicians, painters and writers: Puccini and Catalano, Cannicci and William Storey, Mario Praga and Ugo Ojetti, and above all d’Annunzio, who for many years considered the Origos’ house as his own, wrote the best poems of Alcione at Motrone; and sent to my mother-in-law the only affectionate, unamorous letters he ever wrote to a pretty woman.

It was in this society that Antonio grew up, but as soon as he was old enough to go to school, his father sent him to Switzerland, to be turned into a successful businessman. For a year, afterwards, he worked in a bank in Brussels and then in the champagne firm of Mumms’ in Rheims, but when the First World War broke out he at once joined up. After three years on the Carso and one in the Italian Military Mission in London, he came back to Florence, where we agreed to embark together upon a life entirely new to both of us. Some months before our marriage, we had bought a large, neglected estate, La Foce, in southern Tuscany, hoping to find there not only our home but the work that we both wanted. Antonio had, deep in his bones, the instinctive love of many Italians for the land, and wanted to farm in a region still undeveloped agriculturally, where there would still be much work to do. I had a strong, though uninformed, interest in social work. We both wanted to get away from city life and to lead what we thought of as a pastoral, Virgilian existence.

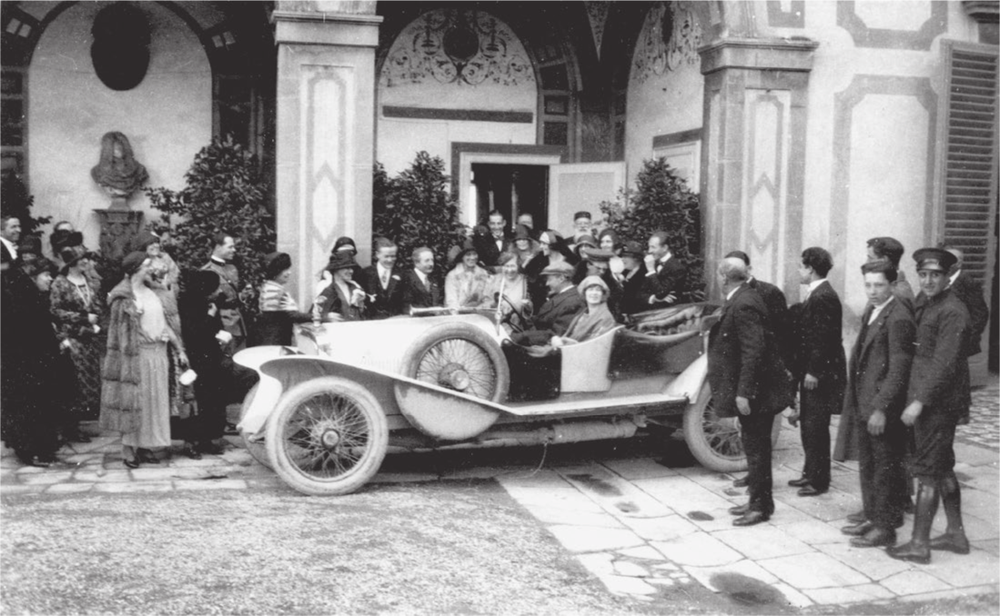

For some more months our marriage was delayed by my mother’s ill-health and mental distress, for her divorce from Geoffrey Scott was just going through, until our family doctor bluntly remarked that if we did not get married at once we never would. So married we were, on March 4, 1924, in the Villa Medici chapel. Only my mother’s sister, Lady Joan Verney, and her son Ulick were there to represent the English side of my family and my aunt, Justine Ward, the American side; with Antonio’s sister, Carla Franceschi, her in-laws, and a handful of our Florentine friends—and Doody to wave us goodbye as we drove away.

Iris and Antonio leave Villa Medici on their wedding day

1 This festa is called Lo Scoppio del Carro. If the fireworks go off well, it is considered an omen for a good harvest.