… superata tellus

Sidera donat.1

BOETHIUS

It was on a stormy October afternoon in 1923, forty-seven years ago, that we first saw the Val d’Orcia and the house that was to be our home. We were soon to be married and had spent many weeks looking at estates for sale, in various parts of Tuscany, but as yet we had found nothing that met our wishes.

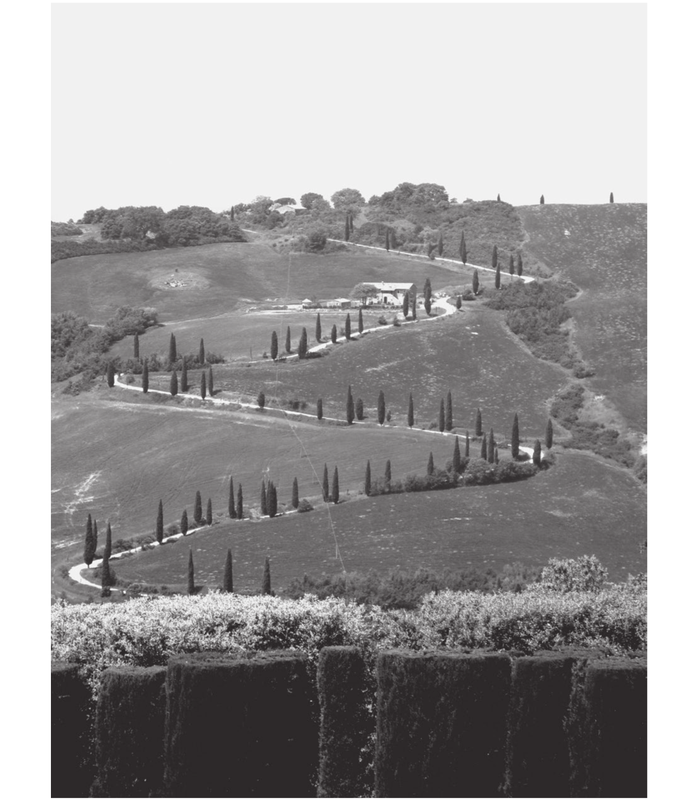

We knew what we were looking for: a place with enough work to fill our lifetime, but we also hoped that it might be in a setting of some beauty. Privately I thought that we might perhaps find one of the fourteenth- or fifteenth-century villas which were then almost as much a part of the Tuscan landscape as the hills on which they stood or the long cypress avenues which led up to them: villas with an austere façade broken only by a deep loggia, high vaulted rooms of perfect proportions, great stone fireplaces, perhaps a little courtyard with a well, and a garden with a fountain and an overgrown hedge of box. (Many such houses are empty now, and crumbling to decay.) What I had not realised, until we started our search, was that such places were only likely to be found on land that had already been tilled for centuries, with terraced hillsides planted with olive-trees, and vineyards that were already fruitful and trim in the days of the Decameron. To choose such an estate would mean that we would only have to follow the course of established custom, handing over all the hard work to our fattore, and casting an occasional paternal eye over what was being done, as it always had been done. This was not what we wanted.

The Val d’Orcia

We still had, however, one property upon our list: some 3,500 acres on what we were told was very poor farming-land in the south of the province of Siena, about five miles from a new little watering-place which was just springing up at Chianciano. It was from there that we drove up a stony, winding road, crossed a ford, and then, after skirting some rather unpromising-looking farm buildings, drove yet farther up a hill on a steep track through some oak coppices. From the top, we hoped to obtain a bird’s-eye view of the whole estate. The road was nothing more than a rough cart-track up which we thought no car had surely ever been before; and the woods on either side had been cut down or neglected. Up and up we climbed, our spirits sinking. Then suddenly we were at the top. We stood on a bare, windswept upland, with the whole of the Val d’Orcia at our feet.

The clay hills (crete senesi) of the Val d’Orcia

It is a wide valley, but in those days it offered no green welcome, no promise of fertile fields. The shapeless rambling riverbed held only a trickle of water, across which some mules were picking their way through a desert of stones. Long ridges of low, bare clay hills—the crete senesi—ran down towards the valley, dividing the landscape into a number of steep, dried-up little water-sheds. Treeless and shrubless but for some tufts of broom, these corrugated ridges formed a lunar landscape, pale and inhuman; on that autumn evening it had the bleakness of the desert, and its fascination. To the south, the black boulders and square tower of Radicofani stood up against the sky—a formidable barrier, as many armies had found, to an invader. But it was to the west that our eyes were drawn: to the summit of the great extinct volcano which, like Fujiyama, dominated and dwarfed the whole landscape around it, and which appeared, indeed, to have been created on an entirely vaster, more majestic scale—Monte Amiata.

The history of that region went back very far. There had already been Etruscan villages and burial-grounds and health-giving springs there in the fifth century B.C.; the chestnut-woods of Monte Amiata had supplied timber for the Roman galleys during the second Punic war, while, from the eighth to the eleventh century, both Lombards and Carolingians had left their traces in the great Benedictine abbeys of S. Antimo and Abbadia San Salvatore, in the pieve of S. Quirico d’Orcia and in innumerable minor Romanesque churches and chapels—some still in use, some half-ruined or used as granaries or storehouses—and the winding road we could just see across the valley still followed almost the same track as one of the most famous mediaeval pilgrims’ roads to Rome, the via francigena, linking this desolate valley with the whole of Christian Europe. Then came the period of castle-building, of violent and truculent nobles—in particular, the Aldobrandeschi, Counts of Santa Fiora, who boasted that they could sleep in a different castle of their own on each night in the year—and who left as their legacy to the Val d’Orcia the half-ruined towers, fortresses and battlements that we could see on almost every hilltop. And just across the valley—its skyline barely visible from where we stood—lay one of the most perfect Renaissance cities, the creation of that worldly, caustic man of letters, Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini, Pope Pius II, the first man of taste in Italy to enjoy with equal discrimination the works of art and those of nature, who would summon, in the summer heat, his Cardinals to confer with him in the chestnut woods of Monte Amiata, ‘under one tree or another, by the sweet murmur of the stream’.

But of all this we knew nothing then, and still less could we foresee that, within our lifetime, those same woods on Monte Amiata, as well as those in which we stood, which for centuries had been a hiding-place for the outlawed and the hunted, would again be a refuge for fugitives: this time for anti-Fascist partisans and for Allied prisoners of war. We only knew at once that this vast, lonely, uncompromising landscape fascinated and compelled us. To live in the shadow of that mysterious mountain, to arrest the erosion of those steep ridges, to turn this bare clay into wheat-fields, to rebuild these farms and see prosperity return to their inhabitants, to restore the greenness of these mutilated woods—that, we were sure, was the life that we wanted.

In the next few days, as we examined the situation more closely, we were brought down to earth again. The estate was then of about 3,500 acres, of which the larger part was then woodland (mostly scrub-oak, although there was one fine beech-wood at the top of the hill) or rather poor grass, while only a small part consisted of good land. Even of this, only a fraction was already planted with vineyards or olive-groves, while much of the arable land also still lay fallow. The buildings were not many: besides the villa itself and the central farm-buildings around it, there were twenty-five outlying farms, some very inaccessible and all in a state of great disrepair and, about a mile away, a small castle called Castelluccio Bifolchi. This was originally the site of one of the Etruscan settlements belonging to the great lucomony of Clusium (as is testified by the fine Etruscan vases found in the necropolis close to the castle, and which now lie in the museum of Chiusi), but the first mention of it in the Middle Ages as a ‘fortified place’ dates only from the tenth century, and we then hear no more about it until the sixteenth, when it played a small part in the long drawn-out war between Siena and Florence for the possession of the Sienese territory—a war which gradually reduced the Val d’Orcia to the state of desolation and solitude in which we found it. In this war Siena was supported by the troops of Charles V and Florence by those of François I of France, and Pope Clement VII (who was secretly allied with the French) made his way one day by a secondary road from the Val d’Orcia to Montepulciano and, on arriving at the Castelluccio, expressed a wish to lunch there. But the owner of the castle, a staunch Ghibelline, refused him admittance, ‘so that the Pope was obliged, with much inconvenience and hunger, to ride on to Montepulciano’.2

This castle, which held within its walls our parish church, dedicated to San Bernardino of Siena, and which owned some 2,150 acres, had once formed a single estate with La Foce; when we first saw it it was still inhabited by an old lady who (even if we had had the money) did not wish to sell. It was not until 1934 that we were able to buy it and thus bring the whole property together again.

As for the villa of La Foce itself, it is believed to have served as a post-house on the road up which Papa Clemente passed, but this is unconfirmed, and the only thing certain is that in 1557 its lands, together with those of the Castelluccio, were handed over to the Sienese hospital of Santa Maria della Scala, as is testified by a shield on the villa and on the older farms, bearing this date, with the stone ladder surmounted by a cross which is the hospital’s emblem. The home itself was certainly not the beautiful villa I had hoped for, but merely a medium-sized country house of quite pleasant proportions, adorned by a loggia on the ground floor, with arches of red brick and a façade with windows framed in the same material. Indoors it had no especial character or charm. A steep stone staircase led straight into a dark central room, lit only by red and blue panes of Victorian glass inserted in the doors, and the smaller rooms leading out of it were papered in dingy, faded colours. The doors were of deal or yellow pitch-pine, the floors of unwaxed, half-broken bricks, and there was a general aroma of must, dust, and decay. There was no garden, since the well was only sufficient for drinking-water, and of course no bathroom. There was no electric light, central heating or telephone.

Beneath the house stood deep wine-cellars, with enormous vats of seasoned oak, some of them large enough to hold 2,200 gallons, and a wing connected the villa with the fattoria (the house inhabited by the agent or fattore and his assistants) while just beyond stood the building in which the olives were pressed and the oil made and stored, the granaries and laundry-shed and wood-shed and, a little further off, the carpenter’s shop, the blacksmith’s and the stables. The small, dark room which served for a school stood next to our kitchen; the ox-carts which carried the wheat, wine, and grapes from the various scattered farms were unloaded in the yard. Thus villa and fattoria formed, according to old Tuscan tradition, a single, closely-connected little world.

Old crumbling farmhouse, which was later taken down and rebuilt

When, however, we came to ask the advice of the farming experts of our acquaintance, they were not encouraging. To farm in the Sienese crete, they said, was an arduous and heart-breaking enterprise: we would need patience, energy—and capital. The soilerosion of centuries must first be arrested, and then we would at once have to turn to re-afforestation, road-building, and planting. The woods, as we had already seen, had been ruthlessly cut down, with no attempt to establish a regular rotation; the olive-trees were ill-pruned, the fields ill-ploughed or fallow, the cattle underfed. For thirty years practically nothing had been spent on any farm implements, fertilisers or repairs. In the half-ruined farms the roofs leaked, the stairs were worn away, many windows were boarded up or stuffed with rags, and the poverty-stricken families (often consisting of more than twenty souls) were huddled together in dark, airless little rooms. In one of these, a few months later, we found, in the same bed, an old man dying and a woman giving birth to a child. There was only the single school in the fattoria, and in many cases the distances were so great and the tracks so bad in winter, that only a few children could attend regularly. The only two roads—to Chianciano and Montepulciano—converged at our house (which stood on the watershed between the Val d’Orcia and Val di Chiana, and thence derived its name), and also ended there. The more remote farms could only be reached by rough cart-tracks and, if we wished to attempt intensive farming, their number should at least be doubled. We would need government subsidies, and also the collaboration of our neighbours, in a district where few landowners had either capital to invest, or any wish to adopt newfangled methods, and we would certainly also meet with opposition from the peasants themselves—illiterate, stubborn, suspicious, and rooted, like countrymen all the world over, in their own ways. We had no lack of warnings. Was it courage, ignorance or mere youth that swept them all away? Five days after our first glimpse of the Val d’Orcia, in November 1923, we had signed the deed of purchase of La Foce. In the following March we were married and, immediately after our honeymoon, we returned to the Val d’Orcia to start our new life.

* * *

How can I recapture the flavour of our first year? After a place has become one’s home, one’s freshness of vision becomes dimmed; the dust of daily life, of plans and complications and disappointments, slowly and inexorably clogs the wheels. But sometimes, even now, some sudden trick of light or unexpected sound will wipe out the intervening years and take me back to those first months of expectation and hope, when each day brought with it some new small achievement, and when we were awaiting, too, the birth of our first child.

For the first time, in that year, I learned what every country child knows: what it is to live among people whose life is not regulated by artificial dates, but by the procession of the seasons: the early spring ploughing before sowing the Indian corn and clover; the lambs in March and April and then the making of the delicious sheep’s-milk cheese, pecorino, which is a speciality of this region, partly because the pasture is rich in thyme, called timo sermillo or popolino. (‘Chi vuol buono il caciolino’, goes a popular saying, ‘mandi le pecore al sermolino.’)3 Then came the hay-making in May, and in June the harvest and the threshing; the vintage in October, the autumn ploughing and sowing; and finally, to conclude the farmer’s year, the gathering of the olives in December, and the making of the oil. The weather became something to be considered, not according to one’s own convenience but the farmer’s needs: each rain-cloud eagerly watched in April and May as it scudded across the sky and rarely fell, in the hope of a kindly wet day to swell the wheat and give a second crop of fodder for the cattle before the long summer’s drought. The nip of late frosts in spring became a menace as great as that of the hot, dry summer wind, or, worse, of the summer hail-storm which would lay low the wheat and destroy the grapes. And in the autumn, after the sowing, our prayers were for soft sweet rain. ‘Il gran freddo di gennaio’, said an old proverb, ‘il mal tempo di febbraio, il vento di marzo, le dolci acque di aprile, le guazze di maggio, il buon mietere di giugno, il buon battere di luglio, e le tre acque di agosto, con la buona stagione, valgon più che il tron di Salmone.’4

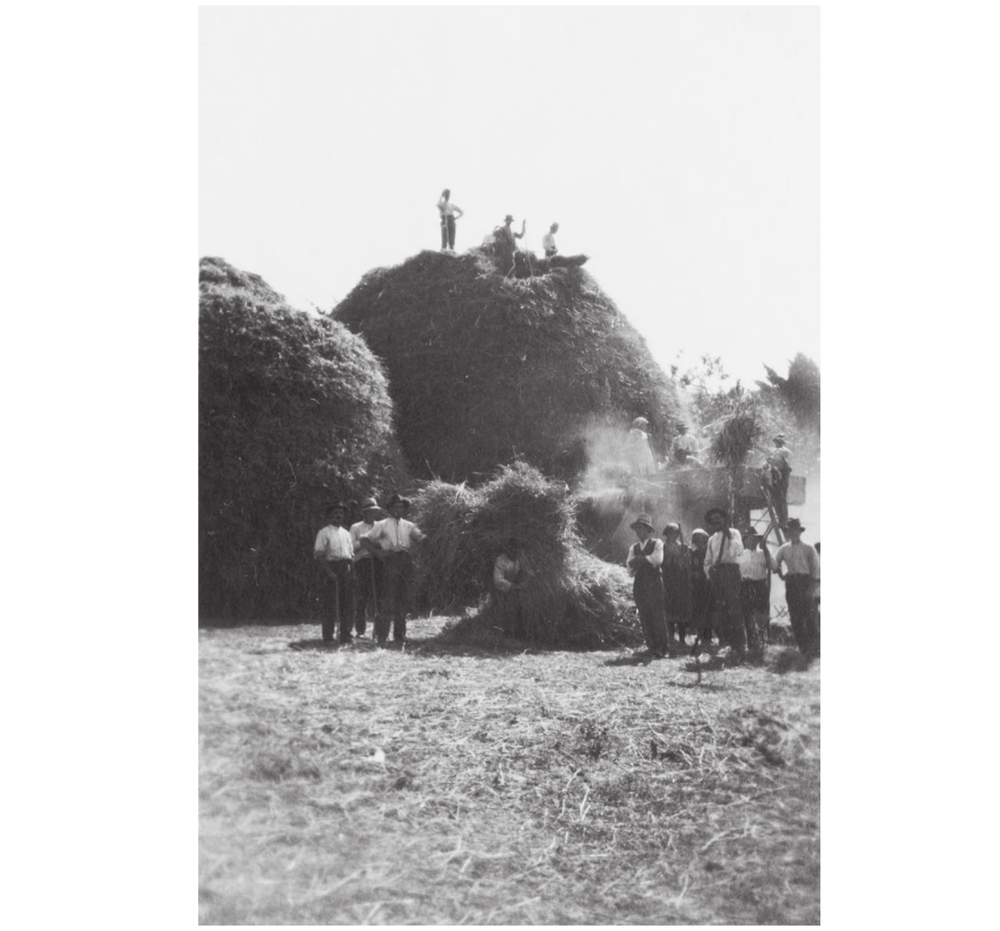

Making haystacks

Some of the farming methods which we saw in those first years became obsolete in Tuscany a long time ago. Then, the reaping was still done by hand and in the wheat-fields, from dawn to sunset, the long rows of reapers moved slowly forwards, chanting rhythmically to follow the rise and fall of the sickle, while behind the binders and gleaners followed, bending low in a gesture as old as Ruth’s. The wine and water, with which at intervals the men freshened their parched throats, were kept in leather gourds in a shady ditch, and several times in the day, besides, the women brought down baskets of bread and cheese and home-cured ham (these snacks were called spuntini) from the farms, and at midday steaming dishes of pastasciutta and meat. A few weeks ago, one of the oldest contadini still left at La Foce, a man of ninety—laudator temporis acti—was reminiscing with my husband about those days. “We worked from dawn to dusk, and sang as we worked. Now the machines do the work—but who feels like singing?”

Lunch in the fields

An even greater occasion than the reaping, was the threshing—the crowning feast-day of the farmer’s year. Threshing, until very recently, had been done by hand with wooden flails on the grass or brick threshing-floor beside each farm, but in our time there was already a threshing-machine worked by steam, and all the neighbouring farmers came to lend a hand and to help in the fine art of building the tall straw ricks, so tightly packed that, later on, slices could be cut out of them, as from a piece of cake. The air was heavy with fine gold dust, shimmering in the sunlight, the wine-flasks were passed from mouth to mouth, the children climbed on to the carts and stacks, and at noon, beside the threshing-floor, there was a banquet. First came soup and smokecured hams, then piled-up dishes of spaghetti, then two kinds of meat—one of which was generally a great gander, l’ocio, fattened for weeks beforehand—and then platters of sheep’s-cheese, made by the massaia herself, followed by the dolce, and an abundance of red wine. These were occasions I shall never forget—the handsome country girls bearing in the stacks of yellow pasta and flask upon flask of wine; the banter and the laughter; the hot sun beating down over the pale valley, now despoiled of its riches; the sense of fulfilment after the long year’s toil.

Then came the vintage. The custom of treading the grapes beneath the peasants’ bare feet—often pictured by northern writers, perhaps on the evidence of Etruscan frescoes, as a gay Bacchanalian scene—was already then a thing of the past. At that time, the bunches of grapes were brought by ox-cart to the fattoria in tall wooden tubs (called bigonci) in which they were vigorously squashed with stout wooden poles, and the mixture of stems, pulp and juice was left to ferment in open vats for a couple of weeks, before being put into barrels, to complete the fermentation during the winter. Now, the stems are separated from the grapes by a machine (called a diraspatrice), before the pressing, and then the juice flows directly into the vats, while for the pale white wine called ‘virgin’ the grapes are skinned before the fermentation (since it is the skin that gives the red wine its colour).

Last, in the farmer’s calendar, came the making of the oil. Unlike Greece and Spain, and some parts of southern Italy, where the olives are allowed to ripen until they fall to the ground (thus producing a much fatter and more acid oil) olives in Tuscany are stripped by hand from the boughs as soon as they reach the right degree of ripeness. Then, when the olives have been brought in by ox-cart to the fattoria and placed on long flat trays, so as not to press upon each other, the oil-making takes place with feverish speed, going on all day and night. When first we arrived, we found that the olives were being ground by a large circular millstone, about two metres in diameter, which was worked by a patient blindfold donkey, walking round and round. The pulp which was left over was then placed into rope baskets and put beneath heavy presses, worked by four strong men pushing at a wooden bar. This produced the first oil, of the finest quality. Then again the whole process was repeated, with a second and stronger press, and the oil was then stored in huge earthenware jars, large enough to contain Ali Baba’s thieves, while the pulp (for nothing is wasted on a Tuscan farm) was sold for the ten per cent of oil which it still contained. (During the war, we even used the kernels for fuel.) The men worked day and night, in shifts of eight hours, naked to the waist, glistening with sweat. At night, by the light of oil lamps, the scene—the men’s dark glistening torsos, their taut muscles, the big grey millstone, the toiling beast, the smell of sweat and oil—had a primeval, Michelangelesque grandeur. Now, in a white-tiled room, electric presses and separators do the same work in a tenth of the time, with far greater efficiency and less human labour, and clients bring their olives to us to be pressed from all over the district. One can hardly deplore the change; yet it is perhaps at least worth while to record it.

Maremmano oxen

One other sight, too, has already almost disappeared from the Val d’Orcia: the big grey maremmano oxen, first brought from the Hungarian steppes to northern Italy, according to tradition, by Attila, and thence to the plains of the Maremma. In our first years in the Val d’Orcia, it was they that were used for ploughing the heavy soil, but then the day came when we bought our first tractor. Never shall I forget escorting it down the valley with a little crowd of admirers, Antonio at their head, to watch it plough its first furrow in a field near the river. Deep, deep went the shining blade into the rich black earth, deeper than a plough had ever sunk before. The children ran behind, laughing and shouting; the pigs followed, thrusting their long black snouts deep into the moist earth. It was an exciting day—but it was, for the oxen (and though we could not then foresee it, for a whole way of life) the beginning of a great change. The first tractor was followed by others, then by a reaper-and-binder and a combine, and after the war, by two bulldozers, to bring under cultivation the parts of the property which still lay fallow. Some oxen continued to be used for ploughing the steeper hillsides, but gradually they were interbred with the finer white oxen from the Val di Chiana, the chianini, while after the war Antonio imported, for beef, the brown and white Simmenthal cattle. You may still sometimes meet a pair of chianini—‘gentle as evening moths’—drawing an ox-cart up a road or driving a plough on a steep hillside; but if you wish to see the grey oxen you must go to those remote hills of the Maremma (and very few are left) where tractors have not yet arrived, or to the few plains by the sea on which they still roam in their pristine freedom or stand on summer days in the deep shade of spreading cork-trees. When all those plains, too, have been handed over to the tractors—and this is swiftly happening—we shall have to go to zoos to find the kings of the Maremma.

I was fascinated in those early days by the survival of some pagan ceremonies and customs, often incorporated, as the Church has sometimes wisely done, into Christian rites. Among the most beautiful ceremonies of the year were the services, after a day of fasting, of the quattro tempora, which were held at the beginning of each of the four seasons, and the ‘rogation’ processions, in which the priest, carrying a crucifix and holy relics, followed by the congregation chanting litanies, walked through the fields, imploring a blessing upon the crops—the women, with black veils upon their heads, joining in the responses, the children straggling in and out and picking wild flowers among the wheat. Both these rites dated back to the days of ancient Rome5 and were still being practised during our first years at La Foce, but they have now come to an end as part of the Church ritual, though I am told that some of the older peasants still hold a brief procession in the fields, and leave a rough wooden cross standing among the ripening wheat.

Other customs, too, linking pagan and Christian piety, were still practised during our first years in the Val d’Orcia, and some of them still survive. On St. Anthony’s Day (St. Anthony the Abbot, patron of animals, not his namesake of Padua) the farmers would bring an armful of hay to church to be blessed by the saint, so that for the whole year their beasts might not lack fodder, and a few of the older men still do so today. On Monte Amiata, on the Eve of the Ascension, some women used to put milk on their window-sills which they would drink the next day, in the hope that swallows would come to bless it. This is perhaps somehow connected with the custom still observed on this side of the valley, of not milking any sheep on Ascension Day. And even now, however deeply imbued with Communism a family may be, each one of them will bring a bunch of olive-branches to be blessed by the priest on Palm Sunday.

On Monte Amiata, too, at Abbadia San Salvatore—where chestnuts form a large part of the poor man’s diet—a procession used to walk through the streets on St. Mark’s Day singing:

San Marcu, nostru avvucatu,

fa che nella castagna non c’entri il bacu.

Trippole e lappole, trippole e lappole, ora pro nobis.6

And only a few years ago a peasant of Rocca d’Orcia, after saying the rosary with his family, used to add an Our Father and a Hail Mary to a saint whom you will find in no calendar, called ‘San Fisco Fosco’, a terrible saint who lived in the middle of the sea and hated the poor, and therefore had to be propitiated.7

Some other practices, too, were quite frankly pagan in origin. There are still both witch-doctors and witches in the villages across the valley, and to one of these, a few years ago, two of our workmen took the bristles of some of our swine, which the vet had not been able to cure of swine-fever. The bristles were examined, a ‘little powder’ was strewn over them, and some herbs were given, to be burnt in their sties—after which the pigs did recover. The same was sometimes done for cattle. There was also a very efficient witch at Campiglia d’Orcia (now dead, but I believe she has a successor) to whom one could take a garment or a hair of anyone suffering from some affliction that the doctor had been unable to heal, and which was presumed to be caused by the evil eye, and she—with the help of some card-reading and some potions—would cure him. Sometimes, however, trouble would be caused by her prescriptions, since two of our tenants’ families embarked on a long feud, merely owing to the fact that she had told the daughter of one of them, that one of her neighbours ‘wished her ill’. For all such cures, it was pointed out to me, faith was necessary: those who came to mock went away unhealed.

Divining of the future, too, was done by some of our older peasants. One of them, an old man who is still alive, specialised in foretelling, in winter, the weather for each month of the following year, by placing in twelve onion skins, named for each month of the year, little heaps of salt. These he would then carefully examine: the skins in which the salt had remained, represented the months of drought; those in which it had dissolved, those of rain.

The most interesting of our local superstitious practices, however—and probably the oldest, since it presumably had its origins in a very primitive form of nature-worship—was one that I myself have seen, that of the poccie lattaie (literally, milk-bearing udders). This took place in a secluded cave on our land, halfway up a very steep ravine, surrounded by dry clay cliffs, but in which a hidden spring, oozing down the walls of the cave, had formed something like stalactites, which had the shape of cows’ and goats’ udders or women’s breasts, each gently dripping a few drops of water. Here the farmers would bring their sterile cows and here, too, came nursing mothers who were losing their milk—and always, after they had tasted the water, their wish was granted. They brought with them, as gifts, seven fruits of the earth: a handful of wheat, barley, corn, rye, vetch, dried peas, and sometimes a saucer of milk.

After nearly half a century, distance has perhaps lent enchantment to these memories, but I must honestly admit that I can also recollect moments of great discouragement. I remember one grey autumn afternoon on which, having ridden on a small grey donkey to visit some remote farms (for there was as yet no road to the valley) I waited alone in a hollow, while Antonio and the fattore walked on to another farm. The cone-shaped clay hillocks in the midst of which I sat were so steep, and worn so bare by centuries of erosion, that even now no attempt has been made to grow anything upon them. Seated beside a tuft of broom—the only plant that will grow there—on ground as hard as a bone after the summer’s drought, I was entirely surrounded by these desolate hillocks: no tree, no patch of green, no trace of human habitation, except against the sky a half-ruined watch-tower, standing where perhaps an Etruscan tower had stood before it, and then a Lombard, rebuilt in the Middle Ages to play its part in a series of petty wars, and now inhabited only by a half-witted shepherd who sat at its foot, beside his ragged flock. Below me lay the fields beside the river—land potentially fertile, but then fallow, which would be flooded when the rains came by the encroaching river-bed. Against the sky, behind the black rocks of Radicofani, dark clouds were gathering for a storm, and, as the wind reached the valley, it raised little whirlpools of dust. Suddenly an overwhelming wave of longing came over me for the gentle, trim Florentine landscape of my childhood or for green English fields and big trees—and most of all, for a pretty house and garden to come home to in the evening. I felt the landscape around me to be alien, inhuman—built on a scale fit for demi-gods and giants, but not for us. How could we ever succeed in taming it, I asked myself, and bring fertility to this desert? Would our whole life go by in a struggle against insuperable odds?

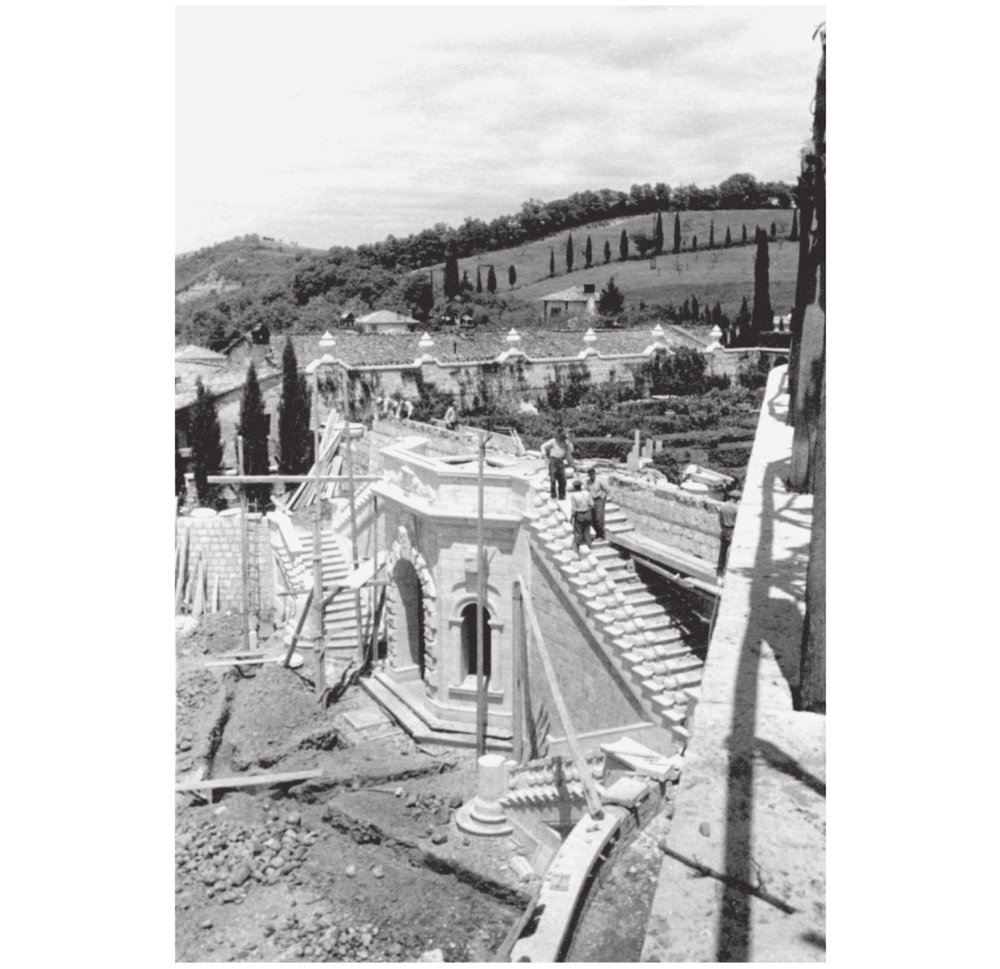

Perhaps my early discouragement was also partly caused by the fact that our own house was not yet habitable. During our absence on our honeymoon, under the direction of our architect and old friend Cecil Pinsent, some indispensable work had been done. A skylight had been opened in the ceiling of the central room, to let in some light; another room had been lined with bookshelves; all had been cleaned and distempered and some open fireplaces, with chimneypieces of travertine from the local quarries of Rapolano, had been added in the library and dining-room; there was even a bathroom, although, as yet, in the dry season, very little water. But that was all. The cases and crates containing all our furniture and belongings were piled up in the dining-room, unlabelled, so that when we began to look for such necessities as sheets or cooking-pans, we would come instead upon a dinner-set of fine Sèvres or a large group of bronze buffaloes, sculpted by Antonio’s father. We settled temporarily in a maid’s room upstairs, and set to work. In a few weeks the house was more or less habitable: the red bricks on the floor had been polished and waxed, the furniture was in place (I did not like all of it, but it was what we had), the windows were hung with chintz or linen curtains, the bookshelves were half filled. (This was the only year of my life in which I have had more than enough book-space.) But there was still, of course, no electric light or telephone, and my greatest wish, a garden, was plainly unattainable till we could get some more water, which was far more urgently needed for the farms. We both agreed that any plans for the house and garden must give way, for the present, to the needs of the land and the tenants. Anything that the crops brought in, as well as any gifts from relations, went straight into the land, and I remember that my present to Antonio, on the first anniversary of our wedding-day, was a pair of young oxen which were led under his window, adorned with gilded horns and with silver stars pasted on their flanks. It is sad to have to add that they were such a bad buy that they had to be sold again as soon as possible.

If there was much satisfaction in these efforts, there was also a certain sense of frustration, which was increased (as our advisers had foreseen) by the passive resistance of our contadini to any innovation. Our land was worked on the system which had been almost universal in Tuscany for nearly six centuries, the mezzadria,—a profit-sharing contract by which the landowner built the farmhouses, kept them in repair, and supplied the capital for the purchase of half the live-stock, seed, fertilisers, machinery, etc., while the tenant—called mezzadro, colono or contadino—contributed, with the members of his family, the labour. When the crops were harvested, owner and tenant (the date I am writing about is 1924) shared the profits in equal shares. In bad years, however, it was the landowner who bore the losses and lent the tenant what was needed to buy his share of seed, cattle, and fertilisers, the tenant paying back his loan when a better year came.

In larger estates, such as La Foce, which consisted of a number of farms, there was generally a central home-farm, the fattoria, usually adjoining the landowner’s house, where the estate manager, the fattore, lived with his family and assistants, and from which the whole place was run. It was the owner (or his fattore) who established the rotations, deciding what was to be grown on each farm, what new livestock or machinery should be purchased, and what repairs were necessary, and it was in the fattoria office that the complicated ledgers and account-books were kept, one for each farm, in which the contadino’s share of all profits and expenses were set down, and also the loans made to him, in bad years, by the central administration. It was in the fattoria cellars and granaries that the owner’s share of the produce was stored; it was there that the wine and oil were made, that the peasants came to unload their ox-carts, to go over their accounts, and to air their requests and grievances—and only those who have lived in Tuscany can know what a slow, repetitive business this can be. The fattoria was, in short, the hub of the life of the estate.

* * *

The origins of the mezzadria system are very easy to describe. After the breaking up of the great feudal estates at the end of the twelfth century, most of the impoverished landowners moved to the rising trading cities (Pisa and Siena, Lucca and Florence), exchanging their former castles and lands for a single grim tower in a city street, while their starving serfs, free or half-free, whose fields and houses had been destroyed by an endless succession of petty wars, also fled to the towns, to find work and bread. Many of them joined one of the guilds, and some eventually turned into skilled craftsmen or opened a small shop, or even became notaries or barbers. In a couple of generations they had saved up a small hoard and since, sooner or later, the Tuscan has always been drawn back to the soil, their first instinct was to put it back into the land again. This was not only true of great merchants like the Bardi or Rucellai, but also of small tradesmen and notaries, who, since they could neither afford to pay overseers nor to leave the town themselves, set a labourer—a colono—to work the land for them, drawing up a very simple profit-sharing contract, which gradually, during the second half of the trecento, came into universal use in Tuscany. The great feudal domain thus turned into a number of small profit-sharing farms or poderi, and the serf of feudal days became a mezzadro or colono. So matters remained for five and a half centuries.

The mezzadria contracts—patti colonici—that we found in use at La Foce were almost identical with those of the fourteenth century, even down to the specification of the small customary gifts from each tenant to the landowner of a couple of fowls or a brace of pigeons, or so many dozens of eggs, on certain feast-days.

Life on each farm, for obvious practical reasons, was still in the patriarchal tradition. The family had to be large, to provide enough hands to work the land, and its head, the capoccia, ruled over his sons and daughters, his sons-in-law and daughters-in-law, with a rule of iron. ‘Tristi quelle case’, said a proverb, ‘dove la gallina canta e il gallo tace’.8 The capoccia’s wife, however, the massaia, had plenty of power in her hands, too. Together she and her husband assigned the work to each member of the family, chose their sons’ brides and, as soon as the grandchildren were old enough to stagger into the woods as small shepherds and swineherds, sent them off to do their share. This manner of life, too, was to come to an end during our lifetime but it was in full swing when we first arrived.

In theory, the great point of the mezzadria was that, though landowner and mezzadro might and did differ on many points, their fundamental interests were alike and, indeed, the partnership could only work in so far as this was so. Certainly, in early days, the sacrifices were not all on one side. We read in the Ricordanze of Odorigo di Credi, a small Florentine landowner of the fourteenth century, that in order to buy the seed for the next year’s wheat he had to pawn his own gown. Moreover there has always been a strong Tuscan tradition with regard to a landlord’s responsibilities towards his tenants. ‘Aid and counsel them’, wrote a fourteenth-century Florentine, Giovanni Morelli, in his Ricordi, ‘whenever any insult or injury is done to them, and be not tardy or slothful in doing so.’9 Any good landowner of our own time, too, until a very few years ago, would have felt this to be his duty; and many of them, if obliged to send away one of their peasants because his family could no longer work the land, would have felt pangs of conscience similar to those felt in 1407 by Ser Lapo Mazzei, a notary and small landowner of Prato. ‘He is so solicitous’, he wrote about his farmer, ‘at the plough and such a fine pruner of vines and so ingenious that I know not how to make a change… and my cowardly or compassionate soul (I wonder which it is) does not know how to say to Moco: “Look for another farm.”’10 A conscientious landowner, too, always placed the welfare of his fields before his personal interests: a considerable proportion of each year’s profits went back into the land. If he did this, the tenant, too, profited, and when a hard year came, there was some margin to fall back upon.

Unfortunately, however, then as now, not all landlords were conscientious, and the bad aspect of the system, from the first, was that an idle or self-indulgent landowner, who did not repair and stock his farms, crippled his peasants, too; while, on the other hand, lazy or dishonest contadini could very swiftly ruin a farm. This was, I think, the origin of the mutual suspicion and dislike which, down the centuries, has all too often come to the surface in the relationship between the contadino and his padrone. Indeed, in some ways the relationship had been better—or at least simpler—in the old feudal days. The feudal lord had often been cruel and had made hard demands upon his serfs; but for all that, he had been much more like them than the new city-folk. To the shopkeeper or lawyer the peasant was merely a dumb brute, who often retorted with the weapons of the under-dog: sullen resentment and craft. Many domestic chronicles and books of precepts of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries testify to this mutual distrust, in accents so similar to those which I have heard upon the lips of some of their descendants today, as to be positively startling. Paolo da Certaldo, for instance, a Florentine merchant, warned his fellow townsmen never to visit their lands on feast-days, when their peasants were gathered together on the threshing-floor, ‘for they all drink and are heated with wine and have their own arms, and there is no reasoning with them. Each one thinks himself a king and wants to speak, for they spend all the week with no-one to talk to but their beasts. Go rather to their fields when they are at work—and thanks to the plough, hoe or spade, you will find them humble and meek.’11

Another prudent landowner, Giovanni Morelli, gave very similar advice: ‘Go round the farm field by field with your peasant, reprove him for work ill-done, estimate the harvest of wheat, wine, barley, oil and fruit, and compare everything with last year’s crops … Trust him not, keep your eye always upon him, and examine the crops everywhere—in the fields, on the threshing-floor and on the scales. Yield not to him in anything, for he will only think that you were bound to do so … And above all, trust none of them.’12

For the other side of the picture we naturally have less evidence, so long as only the rich were literate, but already by the fifteenth century, some of the colono’s resentment had come to the surface in the following rhyme:

Noi ci stiamo tutto l’anno a lavorare

E lor ci stanno al fresco a meriggiare;

Perchè s’ha da dar loro mezzo ricolto,

Se n’abbiam la fatica tutta noi?13

And here are two other sayings, still in popular use, which reflect the feelings of the mezzadro only too plainly:

Ombra di noce e ombra di padrone

sono due ombre buggerone!14

and

Il bene dei padroni è come il vino del fiasco,

che la sera è buono e la mattina è guasto.15

All this hardly suggests an agreeable or stable human relationship, and it has often seemed to me extraordinary that it should have lasted without a break for nearly six centuries. One explanation is apparent if one looks at the Tuscan landscape: the system has produced a highly prosperous agriculture. Those terraced hills with their vineyards and olive-groves, those rich wheat-fields and orchards and vegetable-plots, speak for themselves: they show land as intensively cultivated and fertile as any in the world. But this prosperity is the result of centuries of unremitting hard work. Wherever the Tuscan countryman has been allotted a steep, stony patch of hillside, he has laboriously cleared away the tangled roots of ilex or scrub-oak, the bushes of juniper or myrtle, and dug up the heavy soil, the unwieldy stones and boulders; with the stones he has built, on even the steepest hillsides, little walls to support the terraces on which he could plant his olives and his vines. Selva del mi’ nonno, ulivi del mi’ babbo e vigna mia,16 so the saying runs. In three generations a bare hillside can become a garden.

In addition to this obvious explanation, I think that the duration of the mezzadria has a deeper psychological one. Its strength has lain in an unquestioning conviction on both sides (even with a good deal of grumbling) that the system was, on the whole, fair and equitable; it was this conviction that, for six centuries, made it work. A distinguished Tuscan economist of our own time—Jacopo Mazzei, who himself belonged to a family with a long tradition of responsible land-ownership—justly observed some years ago that the point was not the actual fairness or otherwise of the system itself, but ‘the conviction of its fairness’, which had given it ‘a stability and serenity unequalled in history’.17 On the day that this conviction began to be shaken, he said, the whole system would break down.

* * *

No such thoughts, however, crossed our mind when first we arrived at La Foce. We set to work, untroubled, within the familiar framework. Everything cried out to be done and, had it been possible, everything at once. Re-reading a paper which my husband read to a Florentine agricultural association, I Georgofili, I have found a summary of the work which, on his first arrival, he considered essential and immediate. Its main points were:

(1) To set up, on each farm, an eight-year rotation.18

(2) To start ditching, draining, and the building of dykes and dams on the steep clay hills, and of banks in the river-bed in the valley, so as to be able to cultivate land at present either flooded or water-logged.

(3) To increase further the arable land by arresting erosion on the hillsides, and by extirpating rocks and boulders in the fallow land.

(4) To rebuild and modernise the existing farms, as well as rebuilding the granaries, cellars, store-rooms and machine-sheds of the fattoria, and to renew the whole machinery for making oil.

(5) To increase the acreage of olive-groves and vineyards.

(6) To build new roads.

(7) To build new farms.

(8) To increase the number, and improve the quality of the cattle, sheep, and pigs and, for this purpose, to increase the acreage of alfalfa and clover.

(9) To suspend all cutting down of trees for at least eight years, and then to establish a regular rotation of twelve years’ growth.

(10) To increase facilities for education and medical care.

The programme was a sound one, but its execution was slowed down not only by lack of experience, but of capital. Every penny we had, had been spent on the purchase of the estate, so that all that was left to work with was the allowance of $5,000 a year given me by Grandmamma. On this we started.

I still felt myself, however, very much a stranger in this new world and was not very good at fitting into it. The solid, tradition-bound group of people living in the fattoria—the fattore and his wife and children, his three assistants and the fattoressa (who was never, according to custom, the fattore’s wife, but a woman who cooked and did the baking and the housekeeping and looked after the barn-yard) so deeply rooted in the customs laid down centuries ago, so certain that nothing could or should be changed—made me feel as shy and foreign as the peasant-women who, on certain feast-days, came from their farms on foot or by ox-cart, to place in my hands a couple of squawking fowls, a brace of pigeons or a dozen eggs—and often, too, a flow of grievances, tales of all the family illnesses, or requests for advice and help. But what advice could I give them, when I knew so little myself? Nothing that I had learned at Villa Medici or I Tatti was of any use to me now; I doubt whether any young married woman has started upon her new life more ill-equipped for the particular job she had to do. I did not even know, though Antonio told me that it was my business to concern myself with the fattoria linen-cupboard and the barn-yard, that the sheets, to be durable, should be made of a mixture of cotton and hemp, however scratchy, and that a part of our wool should be laid aside each year, after washing and bleaching, to make new mattresses; I could not distinguish a Leghorn hen from a Rhode Island Red. Nor did I succeed, for a long time, in being as easily cordial as Antonio with everyone we met, nor realise the fine hierarchical distinctions between the fattore and his assistants, the keepers and the foreman, the contadini and the day-labourers. I learned day by day, but never fast enough, always hampered by self-consciousness and shyness, seeming most aloof when I most wished to be friendly. I would walk or ride with Antonio from farm to farm and, while he was busy in the fields or stables, would go into the house and try to make friends with the women and children. It was uphill work. The women were polite—and wary. They offered me fresh raw eggs to drink, or a little glass of sweet home-made liqueur; they showed me the sheep-cheese that they had made, their furniture and their children. But I did not know the right questions to ask; I felt it an impertinence to comment on the way they kept their house, as Antonio said was expected of me; I could not tell one cheese from another; I had no idea whether the baby had measles or chicken-pox, and on the only occasion on which I attempted to give an injection to an old woman with asthma, I broke the syringe. I did better with the children and, when the new schools were opened, I spent a lot of time there—playing with the children during recess, looking at their copy-books, providing them with a small library, admiring their little vegetable- or wheat-plots and giving prizes at the end of the school year—and through the children I gradually got to know the women a little better. It was always a very one-sided relationship though, and hampered by the whole framework of the fattoria between us. If a woman came to ask for her sink to be repaired or for her child to be taken to hospital it had to be referred to the fattore, and sometimes I found that incautious promises I had made had not been carried out. I think, now, that one of the fundamental evils of the mezzadria system was the presence and influence of these middlemen—tougher with the contadini than any landowner, because conscious of being only one step above them, and often shielding the padrone from what they thought it was inconvenient or undesirable for him to know. In our particular case, Antonio was fortunate, particularly in later years, in being surrounded by a group of loyal and devoted collaborators, who have become his close friends, but I still think that the system was a bad one, though perhaps an inevitable consequence of the whole structure of the mezzadria. Always, too, I was distressed by a sense of injustice, by the worn, tired faces of women only a little older than myself, and by the contrast—though certainly at that time we did not live in great luxury—between their life and my own. It is now one of my greatest regrets that inexperience, shyness, and my own other interests so often led me to take the path of least resistance and to leave things as they were.

Antonio, however—simpler, warmer and tougher, and living in a world which he took for granted—went steadily ahead, and it was our good fortune that this was just the period in which the new laws passed by the Fascist government to reclaim the undeveloped regions of Italy were coming into action. The programme—that of the bonifica agraria—included the enforced development, which sometimes led to confiscation, of many large estates in the South, i latifondi, neglected by absentee landlords (who used sometimes to forbid their wretched labourers even to put up any dwelling-place more permanent than a reed hut, for fear that they might acquire ‘squatter’s rights’); the financing of public works on a large scale to stop land erosion; the encouragement of drainage and irrigation; the building of new roads and schools and, subsequently, large State subsidies or loans at low rates of interest to enable active landowners to intensify production and improve the standard of life of their tenants. This ‘battle of the wheat’—which was also accompanied by a good deal of rhetoric, since it formed part of the policy of ‘autarchy’ which was Mussolini’s retort to sanctions—began with the draining of the Pontine Marshes, the cultivation of the plains of the Tuscan Maremma (in which small plots were assigned to war veterans, i combattenti, in the manner of ancient Rome) and a campaign against malaria in Sardinia.19

In some regions, such as ours, where confiscation was unnecessary, landowners’ associations—consorzi di bonifica—were formed, assisted by State subsidies; and it was after Antonio had succeeded in forming (in spite of the opposition of some of his neighbours) one of these consorzi in the Val d’Orcia that we came to work with some men who represented what was best in the Fascist regime: the main initiator of the leggi di bonifica, Professor Arrigo Serpieri (a man of outstanding ability and charm) as well as some able technical experts, who were inspired by an uncritical acceptance of the Fascist slogans, but also by a deep enthusiasm for their work. In the Val d’Orcia, the consorzio was founded in 1930 and Antonio remained its president and moving spirit for over thirty years. An office was opened at Montepulciano, an efficient engineer was engaged, plans were drawn up for government approval, which included work in areas all over the valley from S. Quirico to Radicofani. The state contributions varied from 20% to 100%, according to their nature, while the landowners contributed to the rest in proportion to their acreage and goodwill.20

One of the most urgent tasks was to arrest the erosion on the steep clay hills, and for this purpose Antonio built some twenty-five dams of stone or earth in creeks or gullies as reinforcements against the danger of landslides. Simultaneously, by the building of groynes in the river-bed (consisting of broad walls of masonry jutting out into the stream) the course of the Orcia was controlled, to prevent it from flooding the surrounding fields; and water from the hills above was channelled towards the fallow valley-land and allowed to lie there for four or five years, so that a rich stratum of top-soil gradually raised its level, bringing under cultivation some 150 more acres. Artesian wells were also sunk, under the guidance of water-diviners whose forked willow-twigs often enabled them to forecast not only where water was to be found but at what depth and in what quantity. (This is a much more common gift than is generally believed, and I was delighted to find that I, too, could feel the willow-twig quivering in my hands, as we passed over a water-course.)

An equally urgent problem was that of re-afforestation. Here the government’s Department of Forestry gave us both technical advice and help; two large nurseries of young plants were started, and some 545 acres of hillsides or of ravines were planted with seedlings or young trees (mostly oak, pine and cypress). Now most of these areas are covered by green woods.

Then came the roads. When we first arrived, the only good road ended at our house, and many of the more remote farms could only be reached by rough tracks, almost impassable in bad weather. (I vividly remember, in our first year, the local doctor—an old man—attempting to reach a child stricken with diphtheria in the ox-cart which had been sent to fetch him, sitting bolt upright in his dark town suit on a kitchen chair, while the oxen ploughed on in the deep mud and the distracted father urged them on.) First the old roads were improved or prolonged, and then—on the additional land obtained by the purchase of the Castelluccio—new ones had to be built to link up the isolated farms.

Drilling for water

It is difficult to convey the excitement of this whole enterprise, but perhaps the photographs reproduced here may give some idea of it. Here soil was being turned up that had lain fallow for centuries and, before putting hand to the plough, it was necessary to extirpate and remove enormous boulders, as well as the roots of old trees, and to hold the land up with steep gullies by the building of some more small dykes and dams. This was the work of many months, but when we saw a stretch of new road lying before us, and the tractor could at last begin to turn over the great clods of untilled, shining dark earth, we felt some of the deep satisfaction and fulfilment that must have been felt, far more intensely, by pioneers in new countries, when they saw a desert beginning to turn into a land of promise. By 1940, that is, just before the war, some fifteen miles of new roads had been built on our land, as well as the twenty-five miles of main roads built in the same district by the consorzio di bonifica—each shaded by poplars in the valley or by pines or cypresses higher up—and every farmer was able to bring his produce to market, each child to go to school.

Clearing the land of stones

Next, the farm-houses. I have already described their state on our arrival. Some had to be torn down and entirely rebuilt, others to be repaired, enlarged, provided with modern stables, pig-styes, silos and dung-heaps built on a concrete foundation; wells were sunk or roof-cisterns built for drinking water and ponds made for watering sheep and cattle. Soon, too, modern cooking-stoves stood beside the old hearths with their enormous chimneys, beneath which il nonno used to sit to warm his bones on a winter evening, sometimes beside a broody hen in a basket; a bathroom was installed as well as a modern lavatory and, gradually, each farm was also provided with electric light, and then acquired a radio or television set. The first and most important change, however, was in the actual acreage of the land of each farm, which (after we had increased their number from 25 to 57), came to be of between 75 and 100 acres, instead of over 200, thus rendering intensive cultivation possible. A large part of the newly-cultivated land was sown with wheat, maize and various types of clover, some 6,200 young olive-trees were planted, the vineyards were increased to cover about 200 acres, and the quality of the wine, both white and red, was greatly improved.

New farmhouse

The need for schools was also very urgent since, when we first arrived, eighty per cent of the population could neither read nor write. We had at once organised some evening-classes for adults and moved the school-children into a better room, but now the consorzio built three new schools, one at La Foce and two in the valley. These were run at first along the progressive lines of the country schools around Rome in the agro romano, each school having its own experimental field and garden, so that the children’s lessons bore a close relation to their future life on the land. Later on, however, they were taken over by the State, and are now like any other school. The children’s pride in their new schoolrooms was delightful to witness. I remember that, when the one at La Foce was opened (its walls painted in gay colours and adorned with pictures and maps) we found the pupils, of their own accord, taking off their muddy boots before coming in, so as not to sully the shining floors. (We then provided them with warm slippers to wear indoors.) We also built three small nursery-schools with playgrounds, two in villages across the valley, where many of the women went out to work all day, and one at La Foce, which later turned into the Home for children bombed out of their homes in Genoa and Turin, the Casa dei Bambini described in War in Val d’Orcia21.

The schools were followed by a men’s club with a bowling-green and a general shop beside it and, in 1933, in memory of our son Gianni—who had died the year before—we built what we had come to feel was one of the most urgent needs of the region: a small dispensary or ambulatorio, with an operating-room, a steriliser, four beds for emergency cases, a small stock of infant foods and indispensable medicines, and a flat upstairs for a resident district nurse. The panel doctor from Chianciano (five miles away) came twice a week, and soon his waiting-room was crowded. The nurse also supervised the school-children’s health, but perhaps the most useful of her tasks was her visits to the farms—often forestalling, by timely advice, the outbreak of an epidemic—giving injections, sometimes (but not often) opening windows, persuading young mothers to move their babies from the centre of their double beds into small wicker cribs or baskets, and often, when the midwife or doctor arrived too late, helping a difficult delivery or bringing what relief she could to a deathbed. The ambulatorio beds, too, were often filled—by accident cases, expectant mothers, or convalescent children—and, in addition, the nurse held elementary courses in hygiene for girls and young mothers. Later on, during the war (but this, of course, we did not then foresee) the ambulatorio also fulfilled another purpose: a wounded partisan had a bullet extracted there, another with tuberculosis was nursed during the last weeks of his life and, when an epidemic of virus pneumonia broke out among the partisans hidden in the hill-farms, Signorina Guidetti went secretly at night to nurse them.

The new school at La Foce, with the Casa dei Bambini in the background

By the time that all these buildings were completed, in 1934, we had been at La Foce for ten years: it had become our home. During those years our financial position had been suddenly changed by the death of a distant American cousin, whom I had never seen and of whom I had only heard as an eccentric elderly miser, who, having gone to live abroad ‘to disoblige his family’, had spent his last years in a yacht off the coast of the Isle of Wight, amusing himself (so the legend said) by throwing red-hot coppers into the boat of such solicitous relations as attempted to visit him. He did, however, go to London twice a year to visit his broker—and to some purpose, since the sum which was eventually divided among his surviving cousins was extremely substantial, and enabled us to carry out all the work I have described above much more speedily and thoroughly than would otherwise have been possible.

I shall, however, always be glad that this money did not come to us at once, and that we were obliged, in the first years of our marriage, to count every penny and make some personal sacrifice. Not only did this save us from many mistakes, but it gave a certain basic reality to our efforts. We felt this even at the time—indeed, on the evening on which the news of our change of fortune reached us, Antonio and I were walking up and down the pergola at the end of the day’s work, discussing whether or not his birthday present to me should be a handsome but expensive umbrella which we had seen in a Florentine shop. I pointed out that it would be a great extravagance, since I would certainly lose it; he retorted that I might learn to be more careful—the discussion being only brought to an end by the cable’s arrival. When we had read it and had assimilated its contents, it was with real regret in his voice that Antonio said: ‘I don’t suppose we shall ever argue about buying an umbrella again!’

* * *

Meanwhile—for I have now reached the years between 1935 and 1940—the clouds were gathering all over Europe, and even in our secluded life at La Foce it became impossible not to observe, read, listen and speculate. I read Mein Kampf; I read (as well as hearing) Mussolini’s speeches; I read Rauschning’s Hitler Speaks22 (at that time a very enlightening book to me) and, later on, Fromm’s Escape from Freedom.23 I began at last to read the daily papers and to join the wide captive audience, all the world over, listening to confused, discordant voices coming out of a little box. Not enough has been said, I think, in accounts of our times (since one is always apt to disregard what has come to be taken for granted) about the psychological changes brought about in uninformed civilians by the mere existence of the radio. Never before in history had so many ears been battered by so many voices. Gradually, as I sat before our radio in the library at La Foce, trying to reconcile their messages and sift the small kernel of truth, these voices became for me the true echo of our times. Previously, non-combatants had been, for the most part, only aware of what the Press of their own country told them, or what they saw with their own eyes. Now, we were all constantly exposed to these confusing, overwhelming waves, from friends and enemies alike. Far more than the whistle and crash of falling shells later on, or the dull roar of bomber formations overhead, this cacophony represents my personal nightmare of the years before and during the war. Hitler’s voice with its hysterical screams and the roars of applause that greeted them; Dollfuss’s voice, shortly before his assassination, followed by the promise of his personal friend Mussolini, to support the independence of Austria24 and then, two years later, at the time of the Anschluss, that same friend’s exclamation: “What obligations have we towards Austria? None!”25 Anthony Eden’s voice, urging the League of Nations, if Italy invaded Abyssinia, to a policy of sanctions, and Mussolini’s retort, “L’Italia farà da se!”26 A voice from France, announcing the murder of the Rosselli brothers. Churchill’s voice, declaring that “it is not only Czechoslovakia which is menaced, but also the freedom of the democracy of all nations”—and, only a few weeks later, Neville Chamberlain proclaiming “Peace with honour … peace in our time.”27 Starace’s voice, announcing the decision of the Fascist Grand Council to leave the League of Nations. The voices of soldiers and children, singing the songs of the time:

Dell’Italia nei confini

Son rinati gli Italiani

Li ha rifatti Mussolini

Per la guerra di domani

and

Duce, Duce, chi non saprà morir?28

It is difficult to convey the cumulative impact of these voices, as we sat alone in the library of our isolated country house day after day, and the increasing sense that they brought of inevitable, imminent catastrophe, of the Juggernaut approach of war.

During those years I was still paying frequent visits to England, and there I naturally met, both some ardent supporters of the pacifist movement, in particular its leader, Max Plowman, a man of such transparent goodness and good faith as almost—but not entirely—to convert me to his views, and the writers and journalists who had volunteered to fight in Spain against Franco, and had returned with varying degrees of disillusionment. (I still think George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia the best account of that confused and disturbing time.) I also, through Lilian Bowes Lyon and some Quaker friends, was able to share the efforts of some people who, already then, were devoting their energies to enabling a few Jewish scholars, old people and children, to make their escape from Germany before it was too late. In particular, there was a little school in Kent—largely run by means of Quaker contributions—in which Jewish refugee children from Germany (and soon also from Austria and Czechoslovakia) were brought up in a new-found security and serenity, as citizens of the United Europe of the future.29 Some of them, I remember, gave a highly spirited performance of The Magic Flute in the Chapter House of Canterbury Cathedral.

A good many of these children—especially those living as guests in well-meaning but wholly alien, ultra-British families—were almost ill with homesickness and, among the older ones, with anxiety for their parents and their brothers and sisters who had not come with them. I have never been able to forget the description given to me by one of the Quaker workers in Germany of the agony of mind of the parents obliged to make a choice, when they were told (as was sometimes necessary) that only one child from each family could go. Should it be the most brilliant or the most vulnerable? the one most fitted, or least likely, to survive? Which, if it were one’s own child, would one choose?

The passage from the world of friends concerned with such activities and ideas, and the atmosphere still prevailing in Italy became, whenever I came home, increasingly confusing and distressing. I have a disproportionately vivid memory of a telephone conversation with a woman whom I scarcely knew. She and I had been asked to send a nominal invitation to an old Czechoslovak professor and his wife, which would enable them to get a transit visa through Italy and thus escape from Prague and rejoin their sons in England. “I suppose you’ve done nothing about this preposterous request?” she asked. “Did you have a telegram, too?” I said I had. “I can’t think what came over the woman! She’s my husband’s cousin, not mine; I don’t know her and never want to. Why, she might have got us into trouble!” I said that I thought that was hardly likely, and that it really was a hard case: the professor and his wife were old and ill, longing to join their sons, their only chance, but that, in any case, she need take no further trouble over it. “Trouble! I should think not, indeed! I sent back a pretty firm wire. I have no sympathy with such people. Why didn’t they get out months ago, when their sons ran away? And I don’t believe they’re really Catholics: the name doesn’t sound like it!” An unpleasant undertone in her voice made me cautious. “Well, anyway, I won’t lift a finger to help such people. Those are the cases that get taken up by interfering, hysterical Englishwomen, like that woman who says she’s a friend of yours.” I said that Lilian Bowes Lyon was one of my greatest friends, and rang off. But a few minutes later the telephone rang again; this time the woman’s voice was sharp with curiosity. “You didn’t say what you are doing about it! Now remember, this isn’t a neutral country. You’ve no right to risk getting your husband into trouble. Why, it’s the sort of thing one would hardly do for a member of one’s own family!” Swallowing my anger—which was the sharper for being mixed with a mean little twinge of uneasiness—I hedged, and then, having rung off, sat on the edge of my bed, trembling. The ugly trivial conversation seemed to have a disproportionate importance: it seemed to symbolise all the cowardly, self-protective, arrogant cruelty of the world—our world.

In August, 1939, I drove up with Antonio to Switzerland, for what proved to be our last trip abroad for six years, in order to attend the concerts conducted by Bruno Walter and Toscanini in Lucerne. The day of our arrival was over-shadowed by a typical tragedy of our times. Bruno Walter’s daughter, who had married a young Bavarian Nazi some years before, had moved to Switzerland after the intensification of the Jewish persecution, and was visited there occasionally by her husband. Gradually they had drifted apart, but on the preceding day, he had flown down to Zürich to meet her, and to make a last effort to persuade her to return to Germany with him. When she refused (her sister was in a concentration camp, and many others of her relations and friends were dead or imprisoned) he shot her with his revolver, and then himself.

On that evening the concert was conducted, in Bruno Walter’s stead, by Toscanini, and the programme concluded with Götterdämmerung. The audience filed out in a grim, sad silence, and when we got back to the hotel the late evening news announced the Non-Aggression Pact between Germany and Russia. We all realised its implications.

The next morning, the hotel emptied swiftly—the guests leaving hurriedly for their respective countries. I put through a last telephone call to England, then climbed into the car and drove off with Antonio towards the Italian frontier. My diary30 brings back very vividly my feelings on that day as, after driving up the green, trim little Swiss valleys and lunching on truite au bleu at Martigny, we climbed up the Simplon pass and crossed the frontier. There, sitting beside the customs office, we watched an Italian car which had driven up a few minutes before, being turned back and sent home again.

“No more Italians jaunting abroad now!” said the carabiniere with a friendly grin, as he handed back our passports. “Come in, and stay in!”

The pole of the barrier swung slowly back behind us. I realised that I had made my choice.

But even after this, it was curiously difficult to persuade the Italian man-in-the-street that war, real war, was coming. “You’ll see,” said a taxi-driver, “the Duce will stop at the last moment. He has never made a mistake yet.” We spent a few days in Florence, hanging about waiting for news, and hearing nothing but wild rumours—that an Italian division had been sent from Bologna to Nüremberg—why Nüremberg? That the Duce had had a stroke—that the mysterious passenger that landed in England was Mussolini himself, no, Beck, no, Grandi. There was not even the faintest pretence of martial ardour. ‘It is,’ as a young officer of our acquaintance wrote to his mother, ‘a nonchalant and cold vigil.’

When we got home, we found that two of the fattoria employees had been called up, and several of the farmers’ sons. They were all very upset, but still did not realise that it was anything worse than Abyssinia or Spain. “We’ve had enough of this,” was the refrain, “ora basta. We only ask to be left alone.” We walked from farm to farm on a still, lovely summer’s evening; the grapes ripening, the oxen ploughing. Still blindly they believed: ‘It won’t come to a real war: the Duce will get us out of it somehow.’

Two days later we went round the farms again. Everywhere the older people came hurrying out to meet us, everywhere the same question: “What do you say, sor padrone? Will there be war?” From each family, by now, at least one man had been called up: “My Cecco went yesterday; Assunta’s Beppe had his card this morning. Madonnina bona, what’s going to happen? Who’s going to work the farm?”

On September 3, Antonio and I drove up to visit some friends in a village in the Apennines, and in the villages on the way we saw little groups of recruits and women in tears. Then, as we reached our friends’ house, one of the sons came down to meet us: “Chamberlain’s speech is just over. War is declared.” An hour later the speech was repeated, and all the evening we sat beside the radio, listening to one country after another: Europe moving towards war. I found myself remembering, as many people of my generation must have remembered in England, Grey’s famous phrase in 1914, ‘The lamps are going out all over Europe.’ When would they be lit again?

After the invasion of Poland—overcome by an almost unbearable sense of frustration at my own inaction and uselessness—I went to Rome to see whether there was any organisation whatever in which I could do some form of war work. But I found all doors securely closed. ‘The country’s delicate position—the Vatican’s delicate position …’ I did meet the head of the Polish Institute in Rome, who had been in his youth one of Pilsudski’s legionaries, a tragic and embittered figure, but there was nothing I could do in Italy to help his compatriots, and when an American Relief Mission—headed by Senator Walcott, who had worked with President Hoover on a similar mission some twenty years before—came to the American Embassy in Rome, on their way to Warsaw, I implored the Ambassador31 to ask them to take me with them in any capacity whatsoever. In the same week I discovered that, after seven years of childlessness, I was pregnant. Reluctantly, and feeling more and more useless and cut off, I went back to La Foce.

During the next months—until on June 10, 1940, German pressure caused Italy, too, to enter the war—I found much comfort in seeing, at Montepulciano, the small group of anti-Fascists who gathered together in the house of our friend and neighbour, Margherita Bracci. Her husband was an old friend and brother-officer of my husband’s, and Margherita herself—the daughter of the historian and writer, Francesco Papafava—belonged to an old Paduan family which had always preserved a fine tradition of Liberal thought and feeling. Many of their friends, in the early years of Fascism, had been imprisoned or sent into exile, while most of those who were still in Italy had retired from public life or (often at great personal sacrifice) had resigned from their jobs, and were living in a closed, semi-conspiratorial circle, seeing only the small group of people who shared their opinions and hopes, often embittered and factious, but firmly clinging to their principles and determined to come to no compromise with any aspect of the regime they hated and despised, and which, they were convinced, would lead their country to destruction.

It was with these friends, and with a few others like them in Rome, that I could speak most freely; and yet I remember sometimes coming away from an evening in their company, during which the conversation had the heightened intensity peculiar to minorities under authoritarian governments, with a sense of discouragement. ‘One feels,’ I wrote after one of these occasions, ‘yes, these are enlightened, high-principled, courageous people, but they are not, as yet, of any importance. It is not through them that any change will come.’

I think now that I was mistaken. If I felt a certain sense of unreality in these conversations, it was of course not because this handful of people was not yet able to change the course of events: it was rather because many of them, in their allegiance to an already old-fashioned form of Liberalism, did not see the Fascism they rejected as the glorification of the bourgeoisie which it had already become, but rather naïvely took it at its own face value as a true revolutionary movement, and were also still cut off from the other new political trends in the country which, after the Liberation, swiftly took on a definite shape. All the same, the conversations that then seemed to me unrealistic or sterile were a token that all over Italy there were still men and women whom Fascism had not numbed into conformity. It was they who kept alive the clandestine anti-Fascist press, who kept in touch with foreign books and (when possible) foreign friends, and who fostered the increasing pressure of public opinion which paved the way for the fall of Fascism. Some of them, later on, played an active part in the Resistance movement, others exerted an influence in Court circles at the time of the first negotiations with the Allies, and yet others—when Mussolini had formed the ‘Republic of Salò’ in the north—made their way to the south and joined the Allied forces or formed part of the temporary government in the south or the Committees of Liberation in their respective cities. But I now think that their most important action was in those early, unrewarding years, when many of them lay in prison in Lipari or were confined to remote mountain villages, but still kept alive an incorruptible, unswerving vision of freedom.