Temple

Grandin

I see the world an awful lot like a cow,” explains Temple Grandin. Indeed, it was her love of cows and horses—as well as her ability to know what they are thinking and feeling—that inspired her to overcome the challenges posed by autism and become one of the world’s best-known and best-loved animal scientists.

Mary Temple Grandin was born on August 29, 1947, to a well-to-do Boston family. She grew up attended to by maids and manservants. Because one of the family’s maids was also named Mary, Mr. and Mrs. Grandin started calling their daughter by her middle name, Temple, instead.

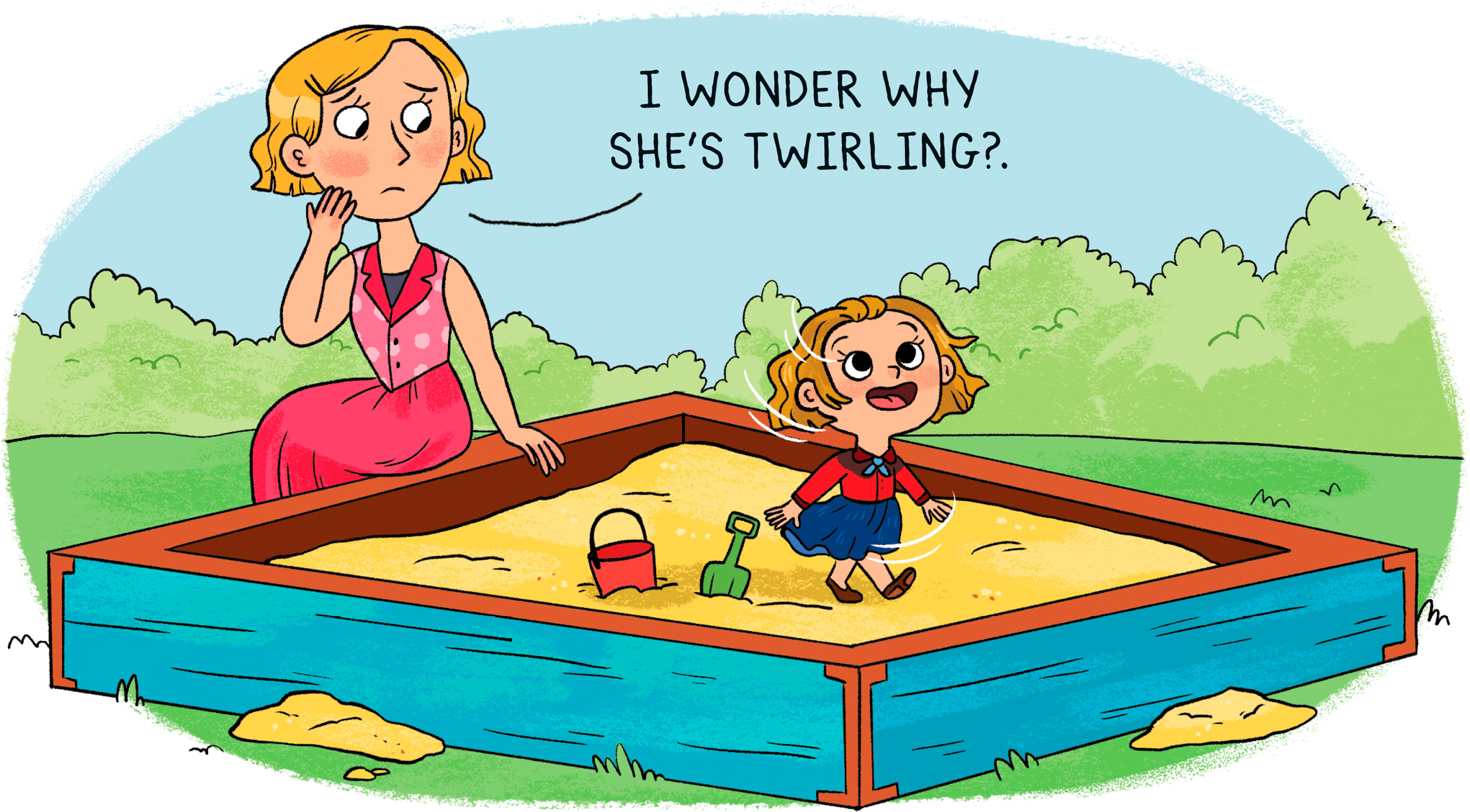

By Temple’s second birthday, her parents could sense that she was different. She didn’t talk or laugh, and she often seemed lost in her own private world. Temple chewed puzzle pieces, stared at flapping flags, and twirled around in a circle for hours on end.

In those days, many people thought these behaviors indicated that a child was mentally ill. Some speculated that Temple might have epilepsy, a disorder that causes seizures. Today we recognize Temple’s behavior as a sign of autism, a condition that affects how the brain works. Autism can make it difficult for people to communicate, understand behaviors, and process sensory information.

Temple explained what autism felt like to her:

“Sometimes I heard and understood and other times sounds or speech reached my brain like the unbearable noise of an onrushing freight train,” she wrote. “I could understand what was being said, but I was unable to respond. Screaming and flapping my hands was my only way to communicate.”

Concerned by their daughter’s inability to speak, Temple’s parents took her to the Boston Children’s Hospital. She stayed overnight in the hospital, sleeping in a small bed surrounded by stuffed animals and dolls.

In the morning, the doctors performed a variety of tests, but could not determine the cause of her speech difficulty. They recommended that Temple see a speech therapist. Temple’s parents also hired a nanny to play board games to keep her brain continuously occupied.

At age four, Temple finally began to talk. Around this same time, doctors were able to diagnose her with what we now call autism. Some of Temple’s doctors recommended that she be sent to live in a mental hospital, but Temple’s mother strongly opposed the idea. She decided to send her daughter to a private school for children with special needs.

At home, Mrs. Grandin worked hard to teach her daughter how to read. Every day for half an hour, she read aloud from an illustrated copy of The Wizard of Oz. Temple was enthralled by the pictures. She got so caught up in the story that soon she was reading entire paragraphs on her own. Before long, Temple was passing her reading tests with flying colors.

Temple also discovered that she had a talent for making things. After reading a book about inventors, she got ideas for projects she could create using everyday objects. She constructed a helicopter from a broken wooden airplane. When she wound the propeller, the toy flew straight up about a hundred feet into the air.

Temple also made bird-shaped paper kites, which she flew behind her bike from a thread. She experimented with bending the wings to make the kites fly higher. Thirty years later, airplane designers began using the same principle as Temple had tried, aiming to improve the performance of commercial airliners.

Just when it seemed as if Temple was progressing in her struggle to communicate, she entered junior high school. Beaver Country Day School was much larger than her elementary school had been. Instead of only thirteen students, her new school had as many as forty students in each class, which were led by a different teacher. The halls were noisy with banging lockers, which made Temple feel anxious and fearful.

Temple also encountered bullies. When she walked down the hallways in her new school, some students called her names because some autistic children have a habit of repeating words and phrases. Temple began to lash out to defend herself. She threw a book at a classmate who taunted her and was expelled from school.

Following her expulsion, Temple’s mother sent her to Mountain Country School, a private boarding school for children with behavioral problems in Rindge, New Hampshire. The environment at this new school was totally different from the one she had left behind.

Surrounded on all sides by acres of woods and streams, Mountain Country School contained a working dairy farm, sheep pens, and a stable with horses for the kids to ride. Temple would later learn that many of the horses there had behavioral problems, too.

“They were pretty, their legs were fine, but emotionally they were a mess,” she wrote of the horses. “The school had nine horses altogether, and two of them couldn’t be ridden at all. Half the horses in that barn had serious psychological problems.”

Temple described one in particular, a horse named Lady. She said that was “a good horse when you rode her in the ring, but on the trail she would go berserk. She would rear, and constantly jump around and prance; you had to hold her back with the bridle or she’d bolt to the barn.”

Then there was an unruly colt called Beauty. “You could ride Beauty, but he had very nasty habits like kicking and biting while you were in the saddle. He would swing his foot up and kick you in the leg or foot, or turn his head around and bite your knee. You had to watch out. Whenever you tried to mount Beauty he kicked and bit—you had both ends coming at you at the same time.”

Worst of all was a beautiful light-brown filly named Goldie, who was perfectly well behaved as long as no one tried to ride her. Goldie was happy to let people pet and groom her, but she broke into a sweat and reared up in terror whenever anyone tried to sit on her back.

“There was no way to ride that horse,” Temple said later. “It was all you could do just to stay in the saddle.”

As a person with autism, Temple could identify with these fearful, anxious animals because she had often felt the same way. As she spent more time around them, Temple began to think that working with special needs animals like Goldie, Beauty, and Lady might just be her calling in life.

So she began spending every spare minute outside the classroom taking care of them. She cleaned their stables, groomed them, and rode them whenever she could. Nothing made her happier than whizzing around the barnyard atop one of her newfound friends.

One day Temple’s mother gave her a special present: a brand-new saddle. It quickly became Temple’s prized possession. She kept it with her at all times, bought saddle soap and leather conditioner, and spent hours alone in her dorm room washing and polishing it until it practically glowed.

A short time later, on a visit to her aunt’s farm in Arizona, Temple watched as a group of cows were being loaded into a cattle chute to get their vaccination shots. At first, the baby calves were anxious and fearful. But they immediately calmed once they were inside the chute, where they were gently squeezed by the four walls that surrounded them.

Fascinated, Temple wondered if a “squeeze machine” would have the same effect on her. So she crawled inside and convinced her aunt to close the chute. In a matter of minutes, the gentle pressure made Temple feel calm, secure, and peaceful. She stayed inside the chute for half an hour. And it was there that she got the idea for her first scientific invention.

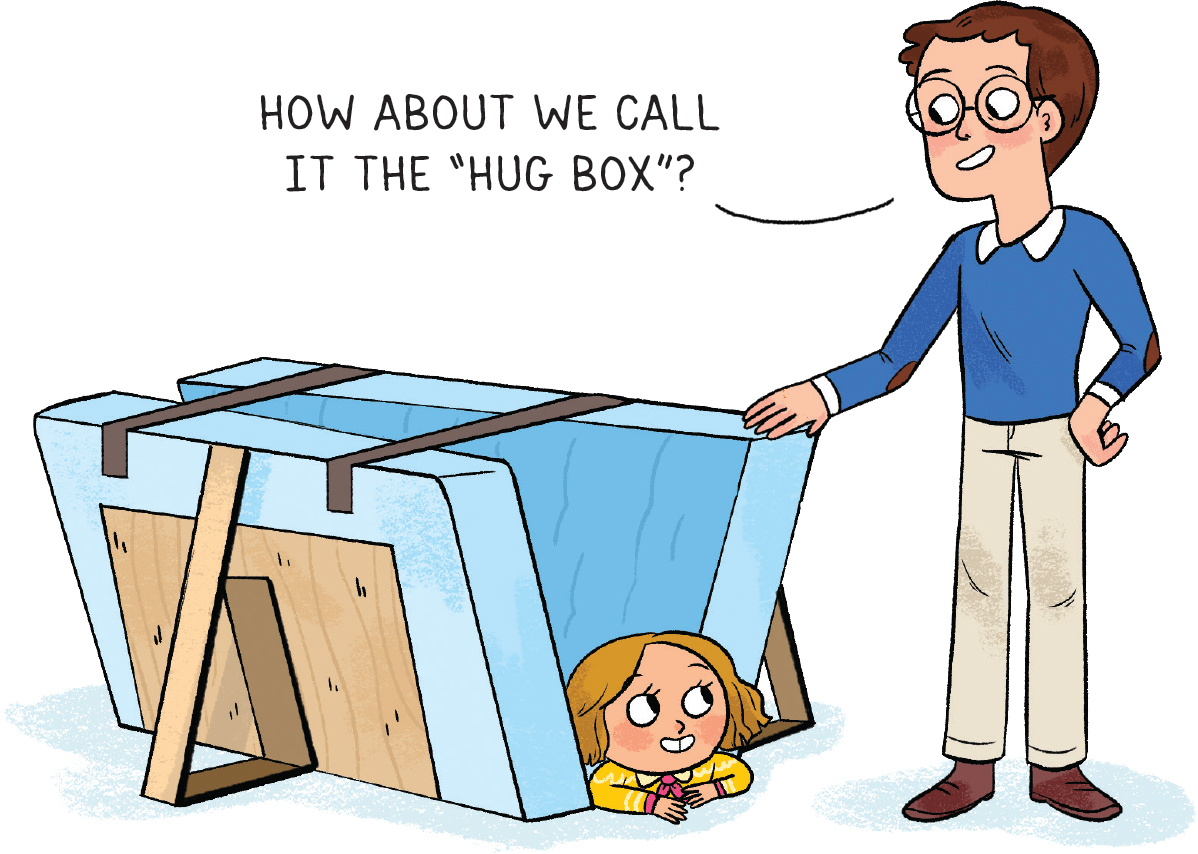

When she returned to school, Temple built her own “squeeze machine” for people like her who suffered from hypersensitivity to light and sound. She showed it to the school’s psychologist, who did not understand what it was and told her to give up on the project.

But Temple knew she was on to something. She brought the device to her science teacher, Mr. Carlock, who instantly grasped its potential. Instead of trying to make her give up the squeeze machine, he offered ideas for improvements and even suggested a catchy new name for it:

Mr. Carlock, who once worked for NASA, then gave Temple an important piece of advice, which she never forgot:

“He told me that if I wanted to find out why it relaxed me, I had to learn science,” she wrote. “If I studied hard enough to get into college, I would be able to learn why pressure had a relaxing effect. Instead of taking my weird device away, he used it to motivate me to study, get good grades, and go to college.”

Temple followed Mr. Carlock’s advice. She worked hard, went to college, and applied the scientific method to gather evidence on the effects of her Hug Box on people and animals. She used the device for many years to relieve the symptoms of her autism.

The Hug Box was a breakthrough that made her name in the world of animal science and inspired the award-winning 2010 movie about her life. Temple Grandin used her new-found fame to advocate for the humane treatment of both people with autism and animals everywhere.