Marie

Curie

The world knows her by her French name, but Marie Curie was the daughter of proud Polish patriots who believed that learning was the key to independence. Long before her radiation research revolutionized science, she fought to get the education she deserved—no matter who tried to stop her.

Marie Curie discovered two new chemical elements—radium and polonium. But her most important achievement may have been the secret laboratory she kept hidden inside her house.

When she was just a toddler, Marie—then known as Manya Sklodowska—liked to play by herself in her father’s study. One day, she noticed a strange object hanging on the wall. It was made of carved, curved brown wood and had a clock-like dial on an oval face. She later learned that it was called a barometer and was used to measure air pressure.

Across the room, she found a locked glass cabinet filled with test tubes, scales, mineral specimens, and something called a gold-leaf electroscope. As she stood on the tips of her toes to get a better look, her father entered the room. She asked:

“Physics apparatus,” he told her.

Smiling, Manya sang the words back to him.

In time, she would come to understand that her father was a scientist, and these were the tools of his trade.

Wladyslaw Sklodowska was known as a well-read and knowledgeable man throughout his hometown of Warsaw, Poland. Manya and her four older siblings called him “the walking encyclopedia” because he was always teaching them something. He loved to entertain his children with informal lessons about science and history. When they went for a hike in the woods, he would point to the sky and explain about the stars. Sometimes the family would spend an entire afternoon re-enacting famous battles using blocks and toys.

But as educated as he was, Manya’s father was not allowed to work as a scientist. At that time, in the late 1800s, Poland was ruled by the Russian Empire. The Russian authorities did not allow Polish citizens to work in laboratories. Mr. Sklodowska was forced to take a job as a school principal.

Wladyslaw and his wife, Bronislawa, were staunch patriots who believed their country should be free from Russian rule. They were convinced that an educated population was the best way for Poland to regain its independence. So when Manya became interested in science, they encouraged their daughter to pursue it.

Manya hoped to continue her education in grade school. But the schools in Warsaw were controlled by the Russians, who closely monitored every classroom. Students were allowed to speak only in Russian. And lessons in Polish history and culture were strictly forbidden.

Despite these restrictions, Manya did exceptionally well. “In spite of everything, I like school,” she wrote in a letter to her best friend Kazia. “Perhaps you will make fun of me, but nevertheless I must tell you that I like it and even that I love it.”

Manya’s Polish teachers devised a scheme to fool the Russian authorities. When no one was looking, they handed out Polish textbooks and started teaching lessons on Polish heritage. When the inspector came to check on them, someone would sound a bell. That was the signal to pull out the Russian textbooks and hide the Polish ones. Since Manya was the star pupil and could read Russian fluently, she was often tasked with reciting the Russian lesson in front of the inspector.

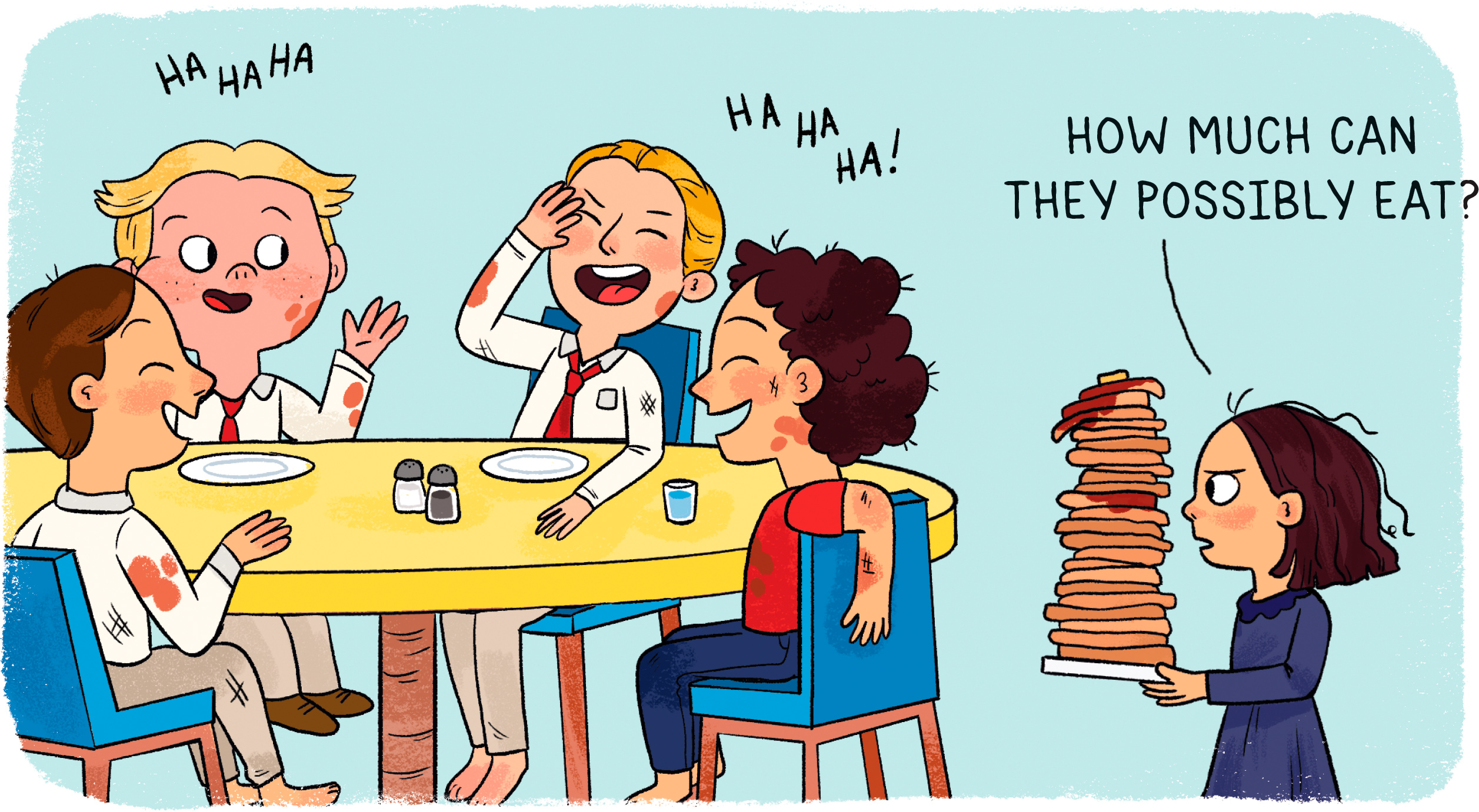

When Manya was ten years old, her life took a turn for the worse. Her mother died of tuberculosis. And her father was fired from his principal’s job and replaced by a Russian. To make ends meet, he turned their house into a boarding school. As many as twenty boys lived in the Sklodowska home. To accommodate them, Manya was forced to sleep on a couch in the dining room. She woke up at six every morning to cook breakfast for the hungry throng.

When she was fifteen, Manya graduated from high school with high honors. She was awarded a gold medal for being the best in her class. But between studying, taking care of her father, and doing the housekeeping, she was exhausted. Her father decided to send her to stay with an aunt and uncle at their house in the country for some much-needed rest.

The planned short vacation turned into a long, leisurely year during which Manya lived a completely carefree life for the first time. With no chores to do, no lessons to learn, and no Russian officials looking over her shoulder, she devoted herself to the simple pleasures of country living: fishing, boating, swimming, and riding horses.

Instead of her usual math and science textbooks, Manya spent her time reading Polish novels. “I can’t believe geometry or algebra ever existed,” she wrote to her friend Kazia. “I have completely forgotten them.” Clad in a brand-new pair of shoes, she danced the night away with her cousins at a fancy ball. When the weather turned cold, she went on sleigh rides in the snow-covered countryside.

Manya also discovered her talent for practical jokes. One of her relatives was a neat freak, so Manya and her cousins pounded nails into the rafters and hung all his furniture upside down. Then they hid nearby until he returned home. The relative was shocked to discover all his possessions—including his shoes—suspended from the ceiling.

The year away from her troubles was just what she needed. Manya returned home feeling refreshed and rejuvenated—ready to continue her education in college. But there was just one catch: The Russian Ministry of Education had issued a decree to every university in Poland, banning women from enrolling.

Fortunately, Manya was used to pulling the wool over the eyes of Russian authorities. She heard about a secret illegal school where Polish women could take college courses in private homes. The teachers were well-read historians, philosophers, and scientists, all of whom believed in the cause of Polish independence. To avoid detection, classes were held after dark in changing locations. It was called the “Floating University.”

For the next few years, Manya worked as a tutor and children’s governess during the day, and attended the Floating University at night. When she got home, if she had time, she read science and mathematics textbooks. On weekends, she conducted experiments in physics and chemistry.

Eventually, Manya had learned enough—and earned enough money—to leave Poland. She moved to Paris, France, where she was able to continue her university studies without having to hide from Russian authorities.

In Paris, she earned two advanced degrees and began to answer to the French version of her name, Marie. She also met and married the French physicist Pierre Curie. Together they made numerous scientific breakthroughs and were awarded the Nobel Prize for physics in 1903. Marie earned a second Nobel Prize, for chemistry, in 1911, making her the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and the first person to win two Nobel Prizes.

Yet no matter how much she accomplished, or by what name people called her, Marie Curie never lost her Polish identity. For the rest of her life, she signed her name “M. Sklodowska Curie.” She also made sure to teach her two daughters to speak Polish as well as French. And when she discovered a new element in 1898, she named it polonium, after the country where she was born.