Stephen

Hawking

Even the greatest geniuses start out small. Stephen Hawking went from building balsa wood airplanes at his friend’s house to mapping out the universe with a supercomputer. His lifelong fascination with the way things work helped turn him into one of the world’s most brilliant theoretical physicists.

“I am just a child that has never grown up,” Stephen Hawking once wrote. “I still keep asking these how and why questions. Occasionally I find an answer.”

Stephen’s search for answers began in the English village of Highgate, a suburb of London. While he was growing up, World War II was raging, and the British capital was subjected to almost daily bombings by German airplanes—a campaign of destruction known as the Blitz.

One day, a German rocket landed just a few houses away from where Stephen lived. He wasn’t home at the time, but later he got to survey the damage and play in the rubble with his friends.

Highgate was home to many prominent scientists, and Stephen’s father was one of them. He worked as a medical researcher specializing in the study of tropical diseases. Stephen’s mother was one of the first female students to graduate from Oxford University. Both of his parents placed a high value on education. But young Stephen did not—at least not yet.

When he was two and a half years old, Stephen’s parents sent him to school. On the first day of class, he stood up in the middle of the room and began to cry. And he did not stop until his parents arrived to bring him home.

After that incident, Stephen didn’t return to school for a year and a half. When he finally did go back, he showed little interest in schoolwork. In fact, he disliked studying so much that he didn’t learn to read until he was eight years old.

Stephen may not have been a fan of school, but he always enjoying learning about things on his own. As a young boy, he developed a passion for model trains. His father built a train set for him out of wood, but Stephen wasn’t happy with it. He wanted one that moved by its own power.

So Stephen’s father tried again. That Christmas, he gave his son a second-hand mechanical train, which he had repaired himself. You could wind it up with a key to make it go, but it didn’t work very well.

He tried yet again. After the end of World War II, Mr. Hawking traveled to the United States on business. He returned with a glittering new mechanical train, complete with a figure-eight track. But Stephen still dreamed of an electric train . . .

Stephen saved his money for years and finally had enough. He waited until his parents were away and then withdrew his entire savings from the bank. All the money Stephen had been given for birthdays and special occasions barely added up to the cost of a new electric train set. But he had just enough.

There was only one small problem—it didn’t work! Even after Stephen scraped together even more money to have the motor repaired, the train still never ran very well. But he had learned a valuable lesson: if you want something to work properly, you have to build it yourself.

When Stephen was eight years old, his family moved to a town north of London called St. Albans, where his father had taken a job. At first, Stephen was excited to be moving into a new home. But then he got a look at the place.

The house had once been an opulent mansion, but now it was a broken-down wreck with peeling wallpaper, holes in the walls, and cracked windows everywhere. Since Mr. Hawking’s new position didn’t pay very much, his parents were unable to pay for repairs. When a piece of furniture wore out, they just let it fall apart. There was no central heating system, so the family had to wear sweaters all the time to keep warm.

Mr. Hawking couldn’t afford to buy a new car, so instead he purchased a used taxicab and asked Stephen to help him build a makeshift garage using prefabricated steel. When the neighbors saw what they were driving, and how they were living, they were aghast. The family soon became known as the town eccentrics.

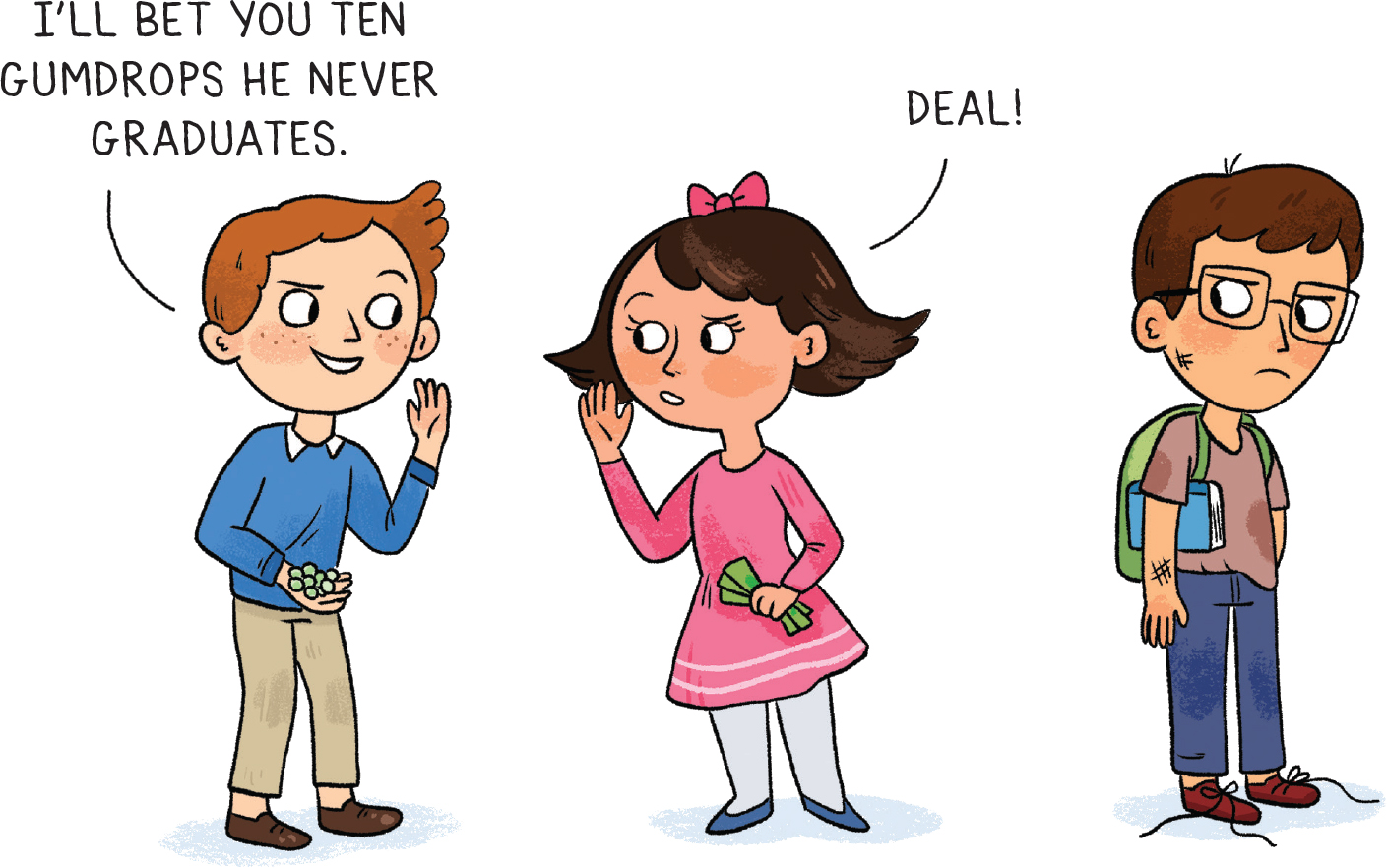

Stephen’s new classmates didn’t quite know what to make of him, either. Small and uncoordinated, Stephen dressed poorly and was bad at sports. He spoke very fast, in a garbled manner that his classmates dubbed “Hawkingese.” He had a strange way of hiccupping when he laughed, almost choking with every chuckle.

In the classroom, Stephen was far from the brilliant student he would one day become. “My handwriting was bad, and I could be lazy,” he later admitted. At the end of the year, he finished third from the bottom of his class. One of his classmates even bet a bag of candy that Stephen would never amount to anything.

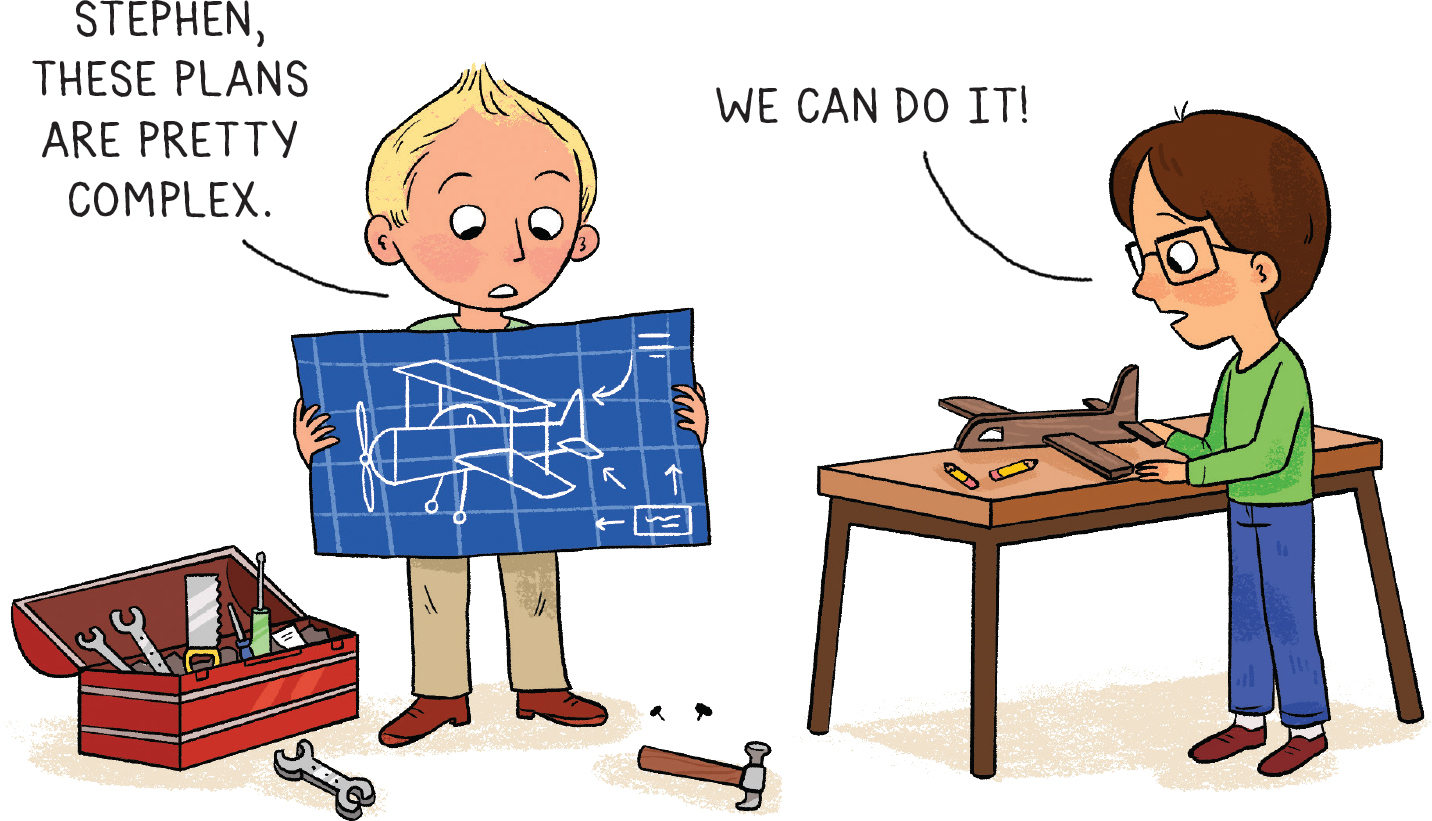

Fed up with being underestimated, Stephen worked hard to turn his reputation around. He began hanging out with other outsiders who shared his passion for building things. He made friends with a boy named John McClenahan, whose father had a workshop in his house. He and Stephen spent hours constructing model airplanes out of balsa wood.

Tired of playing children’s games like Candyland and Uncle Wiggily, Stephen joined forces with another of his friends, Roger Ferneyhough, and together they began inventing their own. Stephen came up with the rules, and Roger designed the boards and pieces. Their masterpiece was an elaborate medieval war game, complete with laws, treaties, budgets, and armies.

For Stephen, making things was like creating his own universe, one that he alone controlled. He became an expert at taking stuff apart, like clocks and radios, although he was not as good at putting them back together. One time he attempted to transform an old television set into an amplifier. But when he plugged it in, he found himself on the receiving end of a 500-volt electric shock.

Failed experiments were few and far between, however. Before long, the same kids who had once bet against Stephen had grown to respect him. They even gave him a new nickname: “Einstein.”

Around this same time, Stephen began to accompany his father to his job at the National Institute for Medica Research. In his laboratory, Mr. Hawking was studying tropical diseases. Together they visited the insect house, which was filled with mosquitos carrying the deadly disease malaria.

Stephen was increasingly fascinated by the world of science. But while his father hoped that he would study medicine or biology, Stephen wanted to chart a different course. As he later wrote: “The brightest boys did mathematics and physics.”

It was at St. Alban’s that Stephen was introduced to the wonders of math, which his teacher Dikran Tahta called “the blueprint of the universe.” That idea appealed to Stephen, who had always been interested in how things were built and designed.

Unlike the classes of most of Stephen’s teachers, his math lessons were lively and exciting. Stephen later credited Mr. Tahta with inspiring him to become a professor of mathematics. “Behind every exceptional person, there is an exceptional teacher,” he wrote.

Mr. Tahta was also the guiding force behind Stephen’s most ambitious project yet. When Stephen was sixteen, shortly before he left for Oxford University, he and his friends decided to construct their own computer. They planned to use recycled clock parts, an old telephone switchboard, and other odds and ends.

It took them a month to get the creaky machine to work, but with a little extra soldering, and a lot of combined brainpower, they were able to patch it together. They called it the Logical Uniselector Computing Engine, or LUCE for short.

Eventually the boys were able to program the computer to solve basic math problems. Their achievement drew the attention of the townspeople, and they were written about in the local newspaper. It was the first of many scientific breakthroughs for which Stephen would be celebrated.

After Stephen left the school, the new computer teacher discovered a box of metal parts and wires. Thinking it was junk, he threw it all in the trash. Only many years later did he discover that the box of scraps was part of Stephen’s great boyhood invention, LUCE.

Stephen Hawking developed ground-breaking theories about black holes, the nature of gravity, and the origin of the universe. He achieved these and many other accomplishments despite having a severe disability called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which he contracted when he was 21 years old. But nothing would stop him from seeking answers to puzzling questions and becoming one of the most respected scientists in the world.