THERE IS A photograph that hangs on the wall of an empty building. In it, a man sits behind a table, looking directly ahead, his eyes betraying nothing. He may be smiling, but it’s impossible to say. He speaks into a microphone, addressing a meeting of Khmer Rouge cadre who are out of shot. He holds the microphone with spindly fingers. I still look at the picture and wonder what he’s saying; whether he’s lecturing his staff on the purity of the revolution or perhaps instructing them on how to extract confessions.

It is a crudely reproduced photograph, copied again and again, badly printed and blown up so that all the midtones have been obliterated. It has been stained over the years and seems to belong to a part of history long forgotten. The original negative is missing and this is the only single portrait known to exist. There was a time when I shuddered just to look at it. And then I began to carry it with me everywhere I went in Cambodia.

The photograph is of Comrade Duch (pronounced Doik), commandant of Tuol Sleng prison. As head of the Khmer Rouge secret police, Duch was personally responsible for the extermination of perhaps as many as 20,000 men, women and children. He was the principle link between Khmer Rouge strategy and the actual mechanics of mass murder. He was Pol Pot’s chief executioner.

On 17 April 1975, Khmer Rouge forces, who had besieged the capital for months, filed into Phnom Penh and declared the dawning of a new era; Cambodia was to begin again. Overnight the Khmer Rouge embarked upon the most radical revolution the world had ever seen. They evacuated the towns and cities, forcing people into the countryside, and mobilised the entire population in their attempt to transform Cambodia into a rural, classless utopia from which few would return. They then closed the borders and Cambodia vanished.

‘Les Khmers rouges’, a term coined by Prince Sihanouk, were a small group of Paris-educated Cambodian communists who began organising against the government in the 1960s. The United States then launched an illegal bombing campaign to dislodge North Vietnamese bases and supply routes inside Cambodia. By the time the bombing was halted, more than a million Cambodians were either dead or wounded and almost half the population had become refugees. Exploiting the devastation in the countryside, the Khmer Rouge overthrew the US-backed regime in 1975.

Four years later, in 1979, the world woke to scenes of a second holocaust. Images of skulls and emaciated children were beamed into living rooms, alerting millions to the sufferings of the people of Cambodia. The entire population had seemingly disappeared for almost four whole years, to emerge battered, tortured, starved, and all but destroyed. A third of the population had died and hundreds of thousands had been executed. Today–a quarter of a century later, and seven years after the death of Pol Pot and the demise of the Khmer Rouge–no-one has yet been held to account for what happened.

I first became aware of Cambodia from a National Geographic article in the early 1980s. Along with the photographs from ancient temples in the jungle were images of mass graves that had just been exhumed. What struck me was how fertile and vibrant the countryside looked. Amid this emerald landscape clothes and skulls were mixed in the chocolate earth, as though the countryside had melted in the midday sun to reveal a terrible secret. When the film The Killing Fields appeared I must have watched it at least fifteen times at various London cinemas. I would sometimes sneak off to see it on my own for fear of ridicule by my peers, as though I was sliding off to watch porn in Soho. At the same time, I began to take an interest in photography and documentary films about conflict. I read avidly. I scoured the bookshelves of London, hoping to get an idea of the country. I wanted to see what Phnom Penh had looked like before, during and after the Khmer Rouge. I couldn’t find anything. It was as if the West had wilfully collaborated with the Khmer Rouge and erased Cambodia from our memories.

For me, Cambodia had become shorthand for all that was wrong in the world. I wanted to understand how a movement that laid claim to a vision of a better world could instead turn people into instruments of overwhelming evil, producing a revolution of unparalleled ferocity. Much of the killing occurred in my lifetime; the secret bombing of Cambodia had begun the year I was born (I have a vague recollection of helicopters on the television), and by the time the Khmer Rouge were in power, rooting out enemies, I was old enough to be one of their victims.

Who were these faceless perpetrators? Like the word ‘terrorist’ the term Khmer Rouge had become so overused that it had ceased to hold any meaning for me, as though they had simply emerged from the flames of the US bombing. Eventually, in the summer of 1989, at the age of nineteen, I left art school for Cambodia to find out for myself. I later moved to Bangkok as a photographer and made frequent trips to the country. I never believed that I would get so close to an answer.

In early 1997, I travelled out to Svay Rieng province, part of the ‘Eastern Zone’ under the Khmer Rouge. It was here that the killing took on a fury unmatched in the rest of the country. Hundreds of thousands perished here and the countryside is littered with mass graves.

The evening was drawing in and the cool breeze rustled the sugar palms that towered above as I followed an old farmer along the dyke. The sun was easing its way down behind the trees ahead, bathing the scene in a golden light. He stopped at an intersection of paddy fields and crouched in front of a small puddle. I did the same, enclosed by a sea of green rice shoots.

The farmer began recounting the scene immediately after the Vietnamese army had driven out the Khmer Rouge. He described how he and others pulled nineteen corpses out of the puddle in front of us. ‘It was deeper then,’ he said. Further on there were more; men, women both young and old. ‘We could smell the bodies,’ he told me. ‘That’s how we found them.’ The Khmer Rouge had used the pagoda as a prison, destroying it before they fled. ‘And they led people to be killed over there,’ he said, pointing to a pile of rubble on the other side of the field.

I sat and nodded in silence. I remember thinking how I couldn’t feel anything and yet I could almost see a film reel flick images past the old man’s eyes, recalled from some secret place in his memory, as he recounted his experiences. ‘At night,’ he said, ‘I can still hear their screams.’

The farmer could see it right there in front of him and all I could think of was how beautiful the scene was and how guilty I felt for thinking that. Over the years travelling through Cambodia I would make pilgrimages to countless local Khmer Rouge execution sites whenever I could. All these visits seemed to do was remind me that, although we occupy the same world, we live in separate universes. The chasm of understanding was as wide as ever.

Tuol Sleng, a former secondary school or lycée, sits in the heart of the capital, Phnom Penh. After their victory, the Khmer Rouge converted the buildings into a secret facility, code-named ‘S-21’, with Comrade Duch as commandant. In keeping with the Khmer Rouge obsession with absolute secrecy, prisoners would arrive at the gates of the prison, often at night, in the deserted Cambodian capital. Here they were tortured to confess to their ‘crimes’. They were accused of working as spies for the KGB, the Vietnamese, the CIA and, in some cases, all three. Afterwards they were taken out of the city and executed. Of the 20,000 who passed through Tuol Sleng’s gates, seven survived.

The prison is now a museum where thousands of mug shots of Comrade Duch’s victims are displayed in the same rooms they were tortured in. The Khmer Rouge, like the Nazis, were meticulous in their record-keeping and thousands of documents and negatives have survived. Names and ages, even height and weight, were recorded.

Over the past sixteen years, on almost every trip I made to Cambodia I wound up at Tuol Sleng, drawn to it by the idea that it might yield answers to some of the questions that stalked my mind. There, I would pore over the archives and the thousands of photographs of victims in an attempt to make sense of what had happened to them. The photographs bear silent testimony to the sufferings of the Cambodian people and it was these images that haunted me. For me, they had become a permanent reminder of the world’s impotence, of our collective guilt in failing to prevent the crime of genocide.

As commandant of Tuol Sleng, Comrade Duch presided over the mechanics of the Khmer Rouge genocide, and was a key witness to it. He was present at many of the interrogations at Tuol Sleng, where a wide variety of torture methods were employed. They ranged from electrical shocks and the pulling out of toenails, to severe beatings and near drownings. His testimony in a trial of former Khmer Rouge leaders would be crucial in upholding the overwhelming evidence that exists of mass murder. The documents kept at the former prison are clear evidence of his guilt, with notations written in his hand ordering executions and details of gruesome methods of interrogation. In one memo a guard asks Duch what to do with nine boys and girls held at the prison who were accused of being traitors. Duch has scrawled across it, ‘kill every last one’.

There were many rumours of Duch’s whereabouts: that he had been killed during one of the many purges of Khmer Rouge ranks; that he was working under a pseudonym for an aid agency in northern Cambodia. He had not been photographed for more than twenty years, and he had never spoken about his role in the killing. It seemed that Duch, like so many others who were responsible for the Cambodian holocaust, had vanished. But with the civil war coming to an end in 1998, and new parts of the country opening up every month, I thought I’d show his photograph to Cambodians I met to see if anyone recognised him. Even if by some incredible coincidence someone did, I knew they would be reluctant to speak. He was a terrifying figure even among the Khmer Rouge. As a fighting force, the Khmer Rouge no longer existed, but former members were everywhere: as government officials, army generals, village leaders. As one Cambodian put it, ‘They are all around us; we live among the tigers.’

Over many years working as a photographer in Cambodia it became clear to me that if we were ever to understand the Cambodian holocaust, and bring any measure of justice, finding Duch and others like him was vital. Duch was the most important witness to those dark years and could shed light on a highly secretive period in his country’s history. And I wanted to know what it was that had turned a seemingly ordinary man from one of the poorer parts of Cambodia into one of the worst mass murderers of the twentieth century.

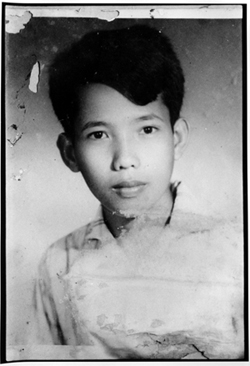

Kaing Guek Eav (Comrade Duch) at the age of about seventeen (Photographer unknown)