The Death Flyer

Lost deep in the ebon tangle and echoing against the starless, sullen sky, the owl’s dismal chatter came like the rattle in a dying man’s throat.

Jim Bellamy paused on the ties, the beat of his heart surging through his throat. The hoot of an owl meant that someone would die.

He forced a smile to his lips at that and shrugged, setting off again through the lonesome tangle which matted the ancient and decayed tracks. He had been a fool to start back this late. He might fall into a hole or through a rotten trestle and break his neck.

But for all his smile, his big shoulders were hunched under his checkered flannel shirt and the scuff of his calks on the gritty cinders fell upon his ears like thunder in the silence.

He had not particularly enjoyed this job of surveying, but in these days, a civil engineer had to take what he could get, even though it meant the tangles and swamps and insects of northern Maine.

He had overstayed himself, checking over his shots. He had sent his crew back to their isolated lumber camp. If anything happened to him that he could not return, they would merely assume that he had chosen to spend the night in the open.

And an inner self or outer self kept telling him that something would happen, that this night was not like other nights. A vibration of unrest was in the air.

He stumbled along the tracks he could not see, and blessed them and cursed them in one breath. This railroad had been deserted for about ten years. Why, he could not exactly remember. Something about their rolling stock going up in smoke. Some wreck or other, he supposed.

Now that his mind was started along that channel, he persisted in digging out fragmentary details of what he had heard. Loggers talk and a civil engineer pretends to listen. Loggers were a superstitious lot, given to tall imaginings.

Yes, he remembered what had happened now. A train had gone through a bridge into a swollen stream and the road had never been able to rebuild for lack of funds and interest on the part of shippers who remembered the incident. It was a shame for all this work to go to waste this way. Rails and ties were still there, all in place. No one in this forgotten forest had had any use for them.

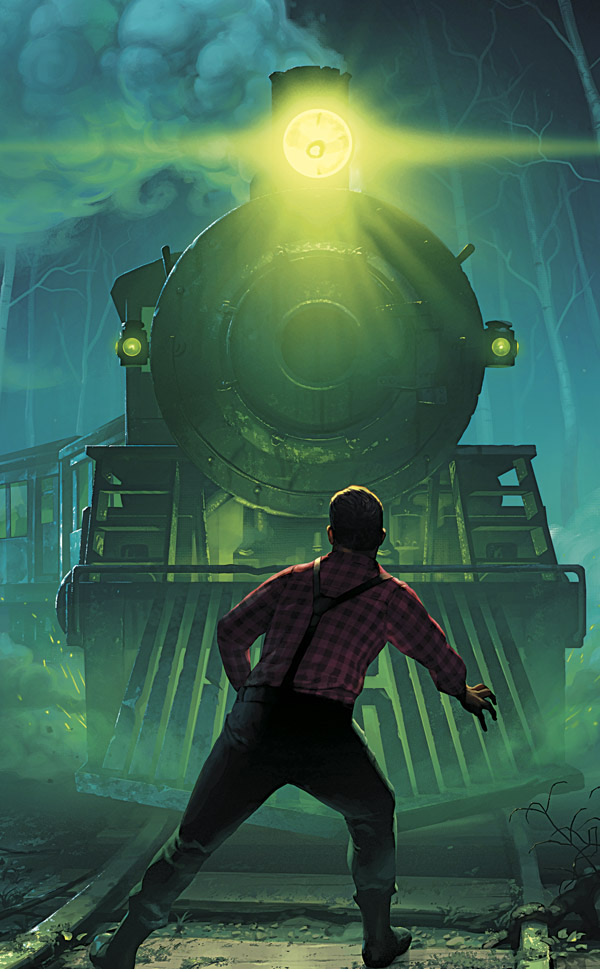

The owl gave his death rattle again. Jim Bellamy quickened his pace. Suddenly he tripped. His stomach felt light. He heard a growing roar reverberate through the trees.

When he tried to get up he was blinded by a yellow eye which grew larger and larger with the noise. He rolled to one side but he could not get off the tracks.

Something was holding his shirt, pinning him down, and the yellow eye stabbed straight through him and held him horror-stricken to the ties.

Good God, it was a train and he was in its path!

The Death Flyer by Ven Locklear

He shut his eyes tightly. The roar shook the earth and through it he seemed to hear the call of the owl which had foretold his death.

A shrill screech bit through the roar and then the thunder died to a hiss. Jim Bellamy sat up. Somehow he was no longer on the track but beside it. A mountain of rust-eaten steel reared up before him. Flame licked out and illuminated a cab. A shadowy face peered down.

“Y’all right, stranger?”

“Sure,” said Bellamy in a shaky voice. “Sure. I’m all right.”

“Well then, why the hell don’t you get aboard? You think I’ve got all night?”

“Sure,” said Bellamy, stumbling up to the tender.

“Not here, you fool. What do ya think we got coaches for? Get back there and get aboard. I’m in a hurry tonight. D’ you realize it’s a quarter past nine?”

Dazedly, Bellamy went back along the line of weather-beaten wooden coaches. Through the dirty windows he could see faces peering curiously at him. The lights which burned in the train, thought Bellamy with a start, threw no reflection on the ground.

He swung himself up into a vestibule which smelled of cinders and soft coal gas and stale cigars and opened the door into a coach. The old-fashioned lamps threw a dismal greenish light along the scarred red plush seats. Half a dozen silent passengers stared moodily ahead, paying him no heed.

Bellamy slid into a seat near the door. The engine panted, the couplings clanked as the engineer took up the slack and then the train went rolling off along the uneven bed.

Bellamy found that he could not think clearly or connectedly. The fall must have given him a nasty crack on the head. Maybe it was worse than he had thought.

He sat motionless for some time. Of his fellow travelers he could see little more than the backs of their heads. There was something unnatural about the way they sat. Tense was the word. Tense and expectant.

A man with dull, corroded brass buttons slouched into the car. His cap was pulled far down over his face and in his gloved hands he held a battered ticket puncher. He came back to where Bellamy sat.

“Ticket, please,” and the voice was weary.

Bellamy sat up straight, staring at the face over him. The flesh hung in loose gouts from under the eyes. The teeth were broken behind black lips. A scar on the forehead bled down over the gray flesh but no blood touched the floor. The eyes were unseen, merely black holes in the ashen putty.

Bellamy recovered his voice. “I have no ticket.”

The empty voice whined a little. “You’re a new one. I never saw you before. We’re late now and I can’t stop to put you off.”

Bellamy fumbled with the breast pocket of his checkered flannel shirt. “I’ll give you the money.”

“Money? I have no need of money. Not now. All I want is your ticket. Haven’t you got a ticket?”

Bellamy detected a motion farther up the car. He saw that the six passengers were getting slowly to their feet and coming back.

They ranged themselves behind the conductor, staring at Bellamy. The air was charged with an evil, decayed smell. Bellamy came halfway to his feet, gripping the edges of the seat, his face blanching.

Not one of those six had visible eyes. Their flesh was the color of dirty lard. Their lips were black and their faces were slashed with many cuts.

A small man, older than the rest, better dressed, pointed a thin, clattering finger at Bellamy. “He is not one of us. He doesn’t belong here!”

Bellamy moved closer to the window. The conductor stood to one side. The six, hands loose at their sides, moved slowly ahead, swaying and jolting under the influence of the train.

It was several seconds before Bellamy understood what they were trying to do. Then he realized that their unseen eyes held the threat of death.

He stood up, crouching forward, and though his face was white, his jaw was stubbornly set.

A lanky thing reached him first. Bellamy lashed out with his fist and rocked the tall body back into the others. But they came slowly on as though they hadn’t seen. The lanky one was with them again.

Bellamy felt like a trapped animal about to be mangled by a hunter. Big as he was, he was no match for six. Fleshless hands reached out and gripped him. Bodies pressed him back.

He struck as hard as he could, twisting and writhing to get away.

Suddenly, above the clatter of steel wheels on rails, a clear, controlled voice said, “Let him be. He does not know.”

The six fell away, backing into the aisle, looking neither to the right nor the left. They were like marionettes on strings, jiggling loosely as the train swayed.

Bellamy braced himself and rubbed at his throat where red marks were beginning to appear. Looking through the six, he was startled to see a young girl in a flame-colored dress poised in the aisle.

Her cheeks were as white as flour, but there was a certain beauty about her which Bellamy could not at once define. She was small, not over five feet four in height. The dress clung to her smooth body and rippled as she moved. Her eyes were dark and sad.

“Go back to your seats,” she said.

The six moved woodenly to their places and seated themselves without a backward glance. But the conductor stood his ground.

“He has no ticket,” said the conductor.

“I have it,” replied the girl with a tired sigh. “I have had it for a long, long while.”

She reached into a small red purse she carried and drew out a crumpled green slip which she handed to the man with the corroded brass buttons. He scanned it, and then punched it with a quick snap.

She watched him open the door and disappear and then she came slowly toward Bellamy and, reaching slowly out, took his hands in hers and sank down across from him, searching his face.

“You do not remember,” she said gently.

Bellamy shook his head. He was too astonished to answer her immediately. Now that she was near to him he could smell the delicate odor of lilies of the valley. Her fine face was uptilted to him and her hands were shaking.

“I have waited long,” she said. “For ten years. And now you have come. I knew that it would be you. The waiting was long but now that you are here, I see that the time was nothing. Please, don’t you remember?”

He could make no answer to her even flow of words. He felt somehow that he should know, that he should remember, but his mind was dull.

“Remember how you wired me?” she went on. “How you said, ‘Whenever you come, I shall be here on this platform, waiting for you’? And now I see that you have tired of waiting and that you have come to me. You see … I could not come to you. I must stay here with these. It is hard sometimes, harder than you know. But now all that is past and you are with me again.”

She raised her slim hand to his face and touched his cheeks. “You are not changed … and though I cannot see you … very well, just to feel you is enough. Please never go away again. I have been so lonely, I have waited so long.”

Bellamy felt as though someone had thrust a dagger into his heart and twisted it there. This girl was almost blind. He was afraid to answer her, afraid that his voice would dispel the illusion she cherished.

But speak he must and although the lump was large in his throat, he said, “No. I won’t leave you … again.”

Then somehow he had gathered her close to him and she was vibrant against him and her breath was warm and sweet upon his face. He held her there for a long time.

“Then it is you after all,” she murmured. “I waited so long.”

The conductor came back, staring at his nickel-plated watch. “He’ll make it. He’ll make it. But there’s only half an hour left.”

The girl shivered against Bellamy. “Must it happen again, now that—”

“Must what happen?” Bellamy demanded with a sudden clarity of mind. He felt like a hypnotized person returning to life.

“Why … why, the wreck, of course. But then you would not know about that. You were waiting. You were not with me then.”

The conductor snapped shut the watch and moved heavily up the car, muttering, “He’ll make it.”

“The wreck?” said Bellamy.

“Yes. This is August the sixteenth, isn’t it? Certainly it must be, otherwise we would not be out. August the sixteenth is the date, don’t you see? Ten years ago tonight. I hate it but there is nothing I can do. Wait, dearest. Wait. Perhaps you can stop it. If anyone does, then it will be over.”

Bellamy felt his mind grow leaden again. But he stood up, pressing her back into the seat. His eyes were staring and his jaw was set. He knew that somehow this was all wrong, that this couldn’t be happening. But it was.

“In ten minutes, they’ll come aboard. They’ll hang out a red lantern and we’ll stop. If you could make them …”

Bellamy stared down at her. His heart was pounding against his ribs and he labored with a problem he could not understand.

A red lantern, eh? And somehow everything would be all right if he could stop this thing. He leaned quickly over her and kissed her soft, moist lips. Then he went up the car past the six passengers. They were still leaning forward staring with their sunken sockets and seeing nothing.

Bellamy swung open the door, walked across the swinging vestibule, pushed open another door and found himself in a baggage car.

The baggage man stared at him and nodded. The baggage man’s face was a black shadow and his hands were white and thin.

“What’s the use, mister?” said the baggage man. “You can’t stop them.”

Bellamy swung on by and went through a door. He crawled up over the tender and looked down on the cab. The fireman was throwing coal into the box, sweat standing out and shining in the light. The fireman worked like a machine and the flames belched redly from the open door.

The engineer turned to stare at Bellamy and Bellamy stared back. The engineer’s face was nothing but a shadow on which was perched the billed cap of his kind. The engineer’s hand was on the throttle, easing it back.

“You can’t do anything,” said the engineer. “Look out. I gotta stop.”

The fireman shoveled with jerky regularity. Bellamy, standing with the firelight hot on his face, said, “Why don’t you try? Just this once. Then—”

“It’s no use, mister. I’ve tried it and I can’t. That’s a red lantern and a flag stop. I got my orders.”

Bellamy saw the man haul on the brake. Steam hissed, steel wheels groaned as they slid on the rails. Bellamy saw they were drawing up to a platform overgrown with long weeds. The station house had gradually collapsed into itself until only a few boards were left—a few boards and the drooping roof beam like a gallows against the sullen sky. An ancient sign creaked and banged in the wind. Once again Bellamy heard the call of the owl and shivered.

Suddenly, beside the cab there appeared a shock of black hair. The man reached for the rungs and swung up to the cab, followed by two other men more ragged and dirty than he.

The first one was tall and thick through the body like a carelessly filled bag of rags. His teeth were yellow and his eyes blazed.

“Pull out,” said the man. “I’m riding here.”

“You can’t ride here,” cried the engineer.

“Who’s to say I can’t?”

“I say you can’t. Not unless you’ve got the orders tonight.”

“What do I care for orders?” The thick one pulled a heavy, sawed-off shotgun from his coat and pointed it at the engineer.

The fireman jumped forward, shovel raised. The gun roared flame redder than the firebox. A black hole went through the fireman’s guts. He fell heavily, clawing at the hot plates, sagging against the boilers. The rank, sickening odor of burning flesh filled the air. One hand was out of sight in the flames.

The engineer jammed the throttle ahead. The train lurched and started. The thick one was laughing and Bellamy smelled whiskey, cheap and strong, upon the fellow’s breath. It had happened so fast that he could do nothing.

The engineer was reaching for his hip pocket where a wrench bulged. One of the others yelled a warning. The thick one sent a roaring blast of flame and lead straight into the engineer’s face. The man sank across his throttles, throwing them wider.

Bellamy was sick with the cold brutality of it. But the scattergun was empty and he saw no other weapons. He jerked up the fireman’s shovel and aimed a blow at the thick one’s skull.

The other two, their faces gray blots in the red flame, leaped ahead to snatch at the handle. Bellamy avoided them. The thick one fumbled for shells.

Bellamy yelled with rage and twisted the shovel free. He saw a blackjack come up with a swift, lethal swing. He dodged. The two men he faced laughed and weaved drunkenly. The blackjack landed at the base of Bellamy’s neck.

Bellamy stumbled. A fist jarred into his chest. He doubled up, almost out, still trying to fight them back. The big one brought down the muzzle of the scattergun and kicked Bellamy back under the fireman’s seat.

Then the three crawled up over the tender and stood for a moment against the sky, shouting at each other to be heard above the roar of the speeding train.

Bellamy, sick and dizzy, crawled out from the corner. He could not think of anything but the girl. These three drunken men were going back toward her. He had heard a snatch of their shouts. That had been enough.

His head was ringing and he could not concentrate. He had the feeling that he was doing wrong to leave the cab but he could not reason why. The engineer was hanging against the throttles, but Bellamy did not understand.

Bellamy crawled up the tender and hitched himself over the coal and down toward the baggage car. He shoved open the door with shaking hands.

The baggage master was sprawled among the shifting trunks. His hands were outstretched and he did not move. The cashbox was standing open, keys jingling in the padlock.

Bellamy went on back. In the vestibule of the first coach he tripped over a sodden lump. He did not stop to inspect it. He plunged on through the empty coach to the second.

His brain was spinning like a maelstrom when he passed through the second vestibule and then his mind went clear again. He peered through the filthy pane of glass.

How long had he been at this? How much time had passed? Somehow that was important above all else.

The passengers were pressed back against the wall. With his scattergun in hand, the thick one held them at bay while his two companions went through pockets and grips. Their shouts were loud and harsh and their faces laughed but not their eyes.

Inside the coach, Bellamy saw a fire ax in its bracket on the wall. Cautiously, he moved the door inward. The thick one’s back was toward him but at any moment one of the passengers might give a sign. One shot at that range from the scattergun …

And then Bellamy saw the girl. She was pressed far back against the rearmost seat, her body tense, her hands thrown back in fear. The thick one reached out with a hard hand and jerked her toward him with a bellowed laugh.

He twisted her wrist until she knelt in the aisle and then, holding the scattergun loosely in one hand, he shifted his grip and snatched at her shoulder. Her lips went white with pain. The thick one laughed again.

“Hold her!” he shouted to his aides.

Bellamy was through the door, ax clutched in his two strong hands.

Suddenly the girl whipped free. The thick one’s knuckles crashed against her eyes. She screamed and sank back on her knees, sinking down into the aisle.

A mad, mad thought raced through Bellamy’s brain. So that’s why she was blind.

He raced the length of the car. One of the aides shouted a warning. The thick one whirled, hair streaming down over his bloated gray face. His yellow teeth flashed and the heavy folds of ashy flesh jumped as he moved.

The scattergun was coming up. Bellamy lashed down with the ax. The blade bit cleanly through the matted hair, through the skull, deep into the face. But the big one stood and the wound did not bleed.

The aides screamed and ran, flashing out through the rear door, but the passengers stood with hands still upraised, without expression or movement.

The thick one tottered backward, clawing at the ax, knees buckling. He stumbled out through the door and out of sight.

Bellamy kneeled beside the girl, lifting her gently and holding her against him.

“It’s all right,” she whispered. “It’s all right. You have come at last. I gave them your ticket here. Perhaps … perhaps … after this there will be … but the train! Good God, stop the train!”

Bellamy stared blankly at her without understanding. She clutched at his shirt, raising herself up. “Please, God, please don’t let him go again. Please let him stop this. Please!”

She buried her face in his shirt and moaned. Suddenly a brain not Bellamy’s took command of him. He started up and faced to the front. He saw the picture of the engineer slouched against the throttles.

Running, he went up the aisle, through the door and down the second coach. He could feel the wheels lifting from the curves under the onslaught of too much speed. The train swayed drunkenly from side to side, threatening to leave the tracks at any moment.

He was aware of someone behind him and he turned back. The girl in red was coming, groping blindly up the aisle, trying to keep up with him.

He swung her into his arms and stepped out into the vestibule. The dead conductor moved restlessly as the train swayed. In the baggage car the baggage master was pinned down under an upset trunk. His arms were still outstretched.

Bellamy pushed the girl up to the tender and followed her. The rocketing perch was hard to hold. Bellamy slid down into the cab. He heard the girl’s scream.

Pulling the engineer away from the throttles, he clutched them and hauled back. He tried to find the brake and could not. Some lever here was the brake. Something on this boiler or in this cab would stop the train. He tripped over the fireman’s body and fell heavily, struggling up even before he hit.

The girl cried out again, her hands on his shoulders, trying to drag him to his feet.

“The trestle!” she cried.

He gripped her arms and looked into her drawn face. It was too late for brakes. Too late for anything.

The front trucks left the rails. The roar of water was under them, far under them. The train went off slowly, slowly, disjointed and lashing.

Space was greedy, sucking the cars down.

Holding the girl close to him, Bellamy braced himself against the crash. He could feel her quiver against him, he could hear the moan of agony which came from her tight throat.

The thunder and crushed steel, the roar of escaping steam, the splinter of rended wood, was suddenly swallowed by the cry of swirling water.

“Don’t … don’t go away from me!”

The voice receded, growing fainter and fainter until it was gone. In its place was the whisper of water against the sand.

Rough hands brought Bellamy to his feet. Daylight blinded him and he was aware of an ache which sent quick lightning flashes through his head when he moved.

Through the swirl of faces about him he could see a crumpled ruin against the bank from which protruded a rust-eaten set of trucks. Farther along he could see the hulk of an old locomotive, bent and twisted and brown under the clear sun.

His eyes focused on the faces and a single thought shot a question from him. “What … have they … where is she?”

“He’s balmy,” remarked a rodman Bellamy suddenly recognized as his own.

“You’d be balmy too, I guess,” retorted a recorder in great heat.

Bellamy’s camp cook was feeling Bellamy’s head. “It’s all right. He ain’t hurt none to speak about.”

“But the wreck!” pleaded Bellamy.

“What wreck?” said the recorder. “You mean this old train here. That fell off the trestle about ten years ago, I reckon. That’s what made ’em shut this line down. About ten years ago it was, and, I think, about this time of the year. But you ain’t been in no wreck, Bel. You stumbled off that trestle in the dark and lit in the soft sand. Some drop, ain’t it? We been looking for you all morning, but you ain’t hurt none.”

“You went a hell of a ways past the lumber camp,” said the cook. “What was the matter? Soused? Don’t tell us you got lost.”

“I … guess I did,” said Bellamy, feeling very weak and dizzy and somehow very sad.

“C’mon,” said the rodman, “we’ll tote you back to camp. Hell, unless you get well right quick, we’ll lose two days or more.”

“We … won’t lose anything,” said Bellamy. “I guess we better be getting back to the job.”

“Okay with us,” said the recorder and helped Bellamy walk up the steep bank. “But I think you’d better lay up for a while. You must have been out for a long time and that ain’t so good.”

Bellamy stopped at the top and looked back at the old wreck half buried in the sand and water. It was rusty and broken and forgotten, somehow forlorn.

A voice seemed to whisper in his ear, “I will be waiting … on the other side. The next time we’ll get through.”

He looked about him, startled, but his survey crew was silent, waiting for him to go on.

He stepped off down the uneven trail and vanished in the twilight of the woods.