Allen J. Grieco

According to a medieval commonplace, human beings were believed to survive by drinking wine (or ale and beer in northern Europe), eating bread, and eating “all those other things” that could be eaten with bread. This third category of foodstuffs was usually referred to by a highly significant Latin term: companagium (companatico in Italian, companage in French). When dealing with medieval food history, this ubiquitous trio turns out to be both a useful and a fundamental way to subdivide human fare, especially when examining the diets of the poor. Economic considerations, but also economic imperatives, limited both the choice of what people ate and how much they ate. This was particularly true in a society where the surplus produced tended to be very limited indeed. Furthermore, even slight price differences seem to have put certain food items beyond the reach of the lower social classes, thus making these products appear as something more linked to the realm of the desired than to what was actually eaten. These very reduced margins within which to make choices, encountered by economic historians whenever they compare the incomes of the working classes to the cost of wheat, would seem to have brought about a very different price structure in the realm of foodstuffs than the one we are familiar with at present.

Grain Consumption and Social Hierarchies

By present-day standards, it might come as a surprise to know that in late medieval and Renaissance Italy the cost of wheat flour—from which bread, the real staff of life, was made—seems to have been abnormally high, especially if we compare its cost to that of meat products. In late-fourteenth-century Florence, for example, one pound of the cheapest meat (pork) cost only twice as much as the best-quality flour, whereas the most expensive meat (veal) cost only two and a half times as much as wheat flour. Today, of course, we are used to a much greater price differential since meat is usually ten to fifteen times more expensive than flour, depending on the kind of meat and the cut. What might seem to have been only a slight price difference must not, however, be underrated since, as I have suggested, it constituted a major discriminating barrier in the eating habits of a large segment of the population, especially in those areas of Europe where wheat and other grains either were used to make bread or were boiled to make a dish of gruel.

It is a commonplace to point out the clear link between bread consumption and social rank. The lower a person’s social rank, the greater the percentage of income spent on bread. For example, historians have found that the percentage of the dietary budget devoted to bread on one of King René’s properties in 1457 varied from a minimum of 32 percent for the overseers to a distinctly higher figure (47 percent) for the cow herders and mule drivers; it reached a maximum of 52 percent among the shepherds, who were considered the lowest-grade workers. The percentage devoted to wine, on the other hand, was less variable, ranging from a minimum of 28 percent for the overseers to a maximum of 34 percent for the shepherds. The most radical discriminant was, however, the percentage devoted to the companagium, the various kinds of food that brought a bit of variety to what was otherwise a diet consisting of vast amounts of bread or gruel. Only 14 percent of the lowly shepherds’ dietary budget was devoted to this item, whereas the overseers, responsible for managing the property, were able to devote as much as 40 percent of their budget to something other than bread and wine. In short, bread occupied an increasingly conspicuous percentile share of the diets of the lower social classes; inversely, this proportion shrank as one rose through the social hierarchy.

This state of affairs does not seem to have been limited to Mediterranean Europe. Christopher Dyer, in Standards of Living in the Later Middle Ages, has shown that the importance of grains (wheat, barley, and oats) was just as fundamental in English peasant diets, even though these were integrated, as in most other European countries, with large quantities of vegetables (onions, garlic, leeks, and cabbage being the most often mentioned) and small quantities of meat and cheese.

In a society where social distinctions were made manifest in a variety of ways, food was an important distinguishing element not only between the different social classes but also between rural and urban culture. Literary texts are particularly sensitive indicators of the social value attributed to different foods and therefore allow us to penetrate the social code with which foodstuffs and meals were invested. For example, any number of literary texts can be found that underscore the fact that the daily use of white bread distinguished the city dwellers from the rural populations, who were more likely to eat bread made with a mixture of grains (wheat or millet, for example) or who, more simply, boiled their grain and ate it in this less refined form. That this distinction was not a purely literary one can be seen from the fact that social and dietary differences were also recognized in the confined spaces of fifteenth-century ships, where at least two different tables existed. According to Benedetto Dei’s report to the Consuls and Masters of the Sea of Pisa in 1471, there was a strict scale of salaries respecting the hierarchy of the men on board ship, just as there were distinctions made in the food served. The owner of the ship and the “officers” were served white bread whereas the rank and file had to be satisfied with rations of dry biscuit.

Literary texts also draw attention to the importance given to the proper choice of foods, especially on public occasions when banquets and meals commemorated an important event linking a given family to the community at large (birth of a child, marriage, knighthood, death). There was, in fact, a fine line between what was considered to be good enough and yet not excessively lavish and, on the other hand, food that could only be considered too poor and therefore not becoming the status of the family and the occasion on which it was being served. An excessive display of wealth was controlled and sanctioned by sumptuary laws promulgated not only by the Italian city-states but also elsewhere in Europe. These laws, an interesting source for food historians, fixed with great precision what foods could be served, how much at a time, and to how many guests. The opposite extreme, too poor a meal, seems to have been a rare occurrence that was usually condemned by the community (only morally speaking, of course) and was considered as reprehensible as excessive luxury.

The diets of the wealthier members of the community, a rather complex but interesting problem, have to be examined using a more sophisticated approach than that of calculating the percentile incidence of bread in their general intake. In fact, for the classes other than the laboring ones, it would seem that social distinctions on the basis of diets became apparent primarily in their choice of foodstuffs other than bread. In this case, however, it is not advisable to use literary texts as a source since they can always be suspected of enunciating rules and regulations that were not observed. There are many other sources—such as letters, travel accounts, and private memoirs—that allow us to penetrate into an everyday world where the direct link between food quality and social status moves from a more theoretical plane to a perfectly explicit one.

An excellent example of this link between food and social status can be found in a letter written in 1404 by Ser Lapo Mazzei, a Florentine notary known to us for his voluminous correspondence with his friend and mentor Francesco de Marco Datini, a rich merchant who lived in the city of Prato. In one of these letters, he wrote thanking his friend for what was meant to be a handsome gift of partridges, but reminding him in no uncertain terms that those birds were not food for his sort of person. In fact, Lapo complains to his friend, saying, “You will not leave me in peace with your partridges and God knows I do not like to destroy so many all at once, considering their price, and I would not give them to the gluttons, and it would grieve my soul were I to sell them.” He then proceeds to explain that, were he still a servant of his people (a euphemism by which he meant sitting in the governing body of the city of Florence), it would then have been his duty to eat such fowl. This statement might seem curious to the present-day reader, but his comment should be taken quite literally. The Signori of Florence were, in fact, required to eat great quantities of partridges and fowl in general, since this was seen as an outward sign of the civic and political power they wielded. Such food, however, was not considered fit for normal people, both in a moral and in a medical sense.

Morally and medically speaking, it was dangerous to eat food that was thought to produce excessive overheating in the human body and therefore lead those who were imprudent enough to eat this way directly from the sin of gluttony (gula) to the closely associated and even more dangerous sin of lust (lussuria). This was something that Lapo must have believed to be true, as most of his contemporaries did, since in another letter to Francesco he only needed to remind him of the partridges he had eaten in Avignon in order to allude to a mistress he had had in that city as a young man. Even a great theologian and preacher like Bernardino of Siena believed that eating fowl could be dangerous; he made a point of telling the assembled crowd in the Piazza del Campo that widows, the subject of this sermon, had to be careful in choosing their food. He reminded them that they had to avoid foods that “heat you up since the danger is great when you have hot blood and eat food that will make you even hotter.” In particular, he pointed out: “Let me tell you, widow, that you cannot eat this or that…. Do not try to do as you did when you had a husband and ate the flesh of fowl.”

In any case, Lapo made it clear that such presents were not welcome, but that if his wealthy friend wanted to give him some coarser foods, fit for working people, this he would accept with pleasure. Lapo, it must be said, had not changed much over the years; in a letter he wrote some fourteen years earlier, when he first met Francesco, he told his new friend, “I like coarse foods, those that make me strong enough to sustain the work I must do to maintain my family. This year I would like to have, as I once had, a little barrel of salted anchovies.”

The nutritional guidelines followed by Lapo did not apply to everyone. In fact, his friend Francesco was quick to break these rules, and his diet continued to be, even after the Avignon interlude, the diet of a man who was anything but temperate. From the study by Iris Origo, The Merchant of Prato, it is quite obvious that for Francesco di Marco Datini, as for many of his contemporaries, food was not a neutral matter and that his social status was seen to be closely linked to the kind of food he managed to buy. Thus, meat that was not worthy of him could unleash what seems to us to have been an excessive reaction. On one occasion he was sent some veal that was not up to par (probably from an animal that was too old). His reaction was to write to the agent and tell him, “You should feel shame to send such meat to as great a merchant as I am! I will come and eat it in your house, and only then shall we be friends again!”

The notion of “good” meat being fit mainly for the higher social strata and lower-quality meats being fit for the less elevated members of society (considered to be a “scientific” fact even by the doctors writing about diets) is borne out by another of Datini’s letters. In this letter he asks a man by the name of Bellozzo to go to the market “where there are most people and say, ‘give me some fine veal for that gentleman from Prato,’ and they will give you some that is good.” For a man that was so conscious of his status and the food that went with it, it became a matter of some importance if he managed (or, for that matter, did not manage) to buy the same food that was allotted to the priors of Florence whose high table (mensa dei signori) saw the best food to be had in Florence. On various occasions he either complained that the Signori of Florence had bought up the best fish available or was able to boast to his wife that he had bought the same veal that was reserved for the priors.

Even literary texts bear out the fact that it was considered quite normal for items of exceptionally large size, as long as they belonged to what was considered a noble food such as fish or fowl, to be destined for exceptional people, usually the local ruler. According to one of these stories, probably more than just a literary topos, a pair of exceptionally large capons appeared on the market in Milan where they were immediately bought up by a gentleman who, far from having them cooked for his own table, thought it fitting to send them as a present to Bernabò Visconti, the ruler of Milan.

At times hierarchical distinctions were observed in an even more extreme way—to the point of seeming an overdetermined mechanical exercise. A particularly good example of this is seen in the meals served to two Bavarian princes who visited Florence with their retinue in 1592. This group of visiting dignitaries and their hangers-on were offered a diversified meal that was meant to respect the social hierarchies at play. Thus, the two princes were served a dish with five different fowl (fowl being the noblest food possible). The “second table” (the one for the nobility accompanying the princes) was served dishes with only four different fowl. The cupbearer and the other top-ranking “servants” were also given dishes with four different fowl, but they were to eat their food in a private room separate from the banquet hall. Then came the lower-ranking servants (thirty in all) who had to share five dishes with one fowl each. These servants ate in the tinello, a kind of antechamber used for this purpose. The document then specifies that the horses and mules of the visitors were to be taken care of. The last to be mentioned in the list, even after the animals, were the very lowest ranking servants (a total of 140), who were put up in two different hostels in the city. Hierarchies were thus expressed not only in terms of the diversity of food served but also in terms of where the food was consumed (the distance from the master seeming to be the measure).

Food and Worldview

These distinctions through food, whereby the upper classes were meant to eat more “refined” foods, leaving coarser foodstuffs to the lower classes, were commonplace. Sixteenth-century treatises on the nobility examined this problem and reminded their readers that the “superiority” of the more refined part of the society was due, at least in part, to the way in which they ate. Thus, Florentin Thierriat in his Discours de la préférence de la noblesse asserted that “we eat more partridges and other delicate meats than they [those who are not of the nobility] do and this gives us a more supple intelligence and sensibility than those who eat beef and pork.”

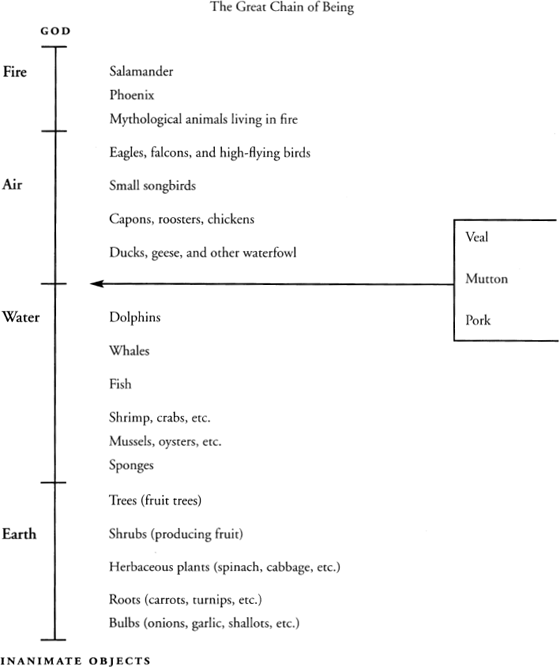

All of the examples cited above suggest that there was something like a code that made a meal noble or poor and that this code was not a personal one but rather one known and shared by most people. The idea that the rich and poor were meant to eat in very different ways may seem more or less senseless to us today, but in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance the idea was grounded in a set of theories that were believed to be objective. According to the prevailing worldview, there existed a series of analogies between the natural world created by God and the world of human beings. It seemed self-evident that God had created the world as well as the laws that governed human society, both being structured by a vertical and hierarchical principle. Human society was, quite obviously, subdivided in a hierarchical way, but it was also thought that nature itself had been created as a kind of ladder, usually referred to as the Great Chain of Being (see above). This great chain was thought to give a particular order to nature since it not only connected the world of inanimate objects to God but also linked all of creation together in a grand design. Between the two extremes of the chain were to be found all the plants and animals created by God (including even mythological animals such as the phoenix). Furthermore, God’s creation was thought to be a perfectly hierarchical entity in which everything respected an ascending or descending order. Each plant or animal was thought to be nobler than the one below it and less noble than the one above it, so no two plants and no two animals could have the same degree of nobility.

The Chain of Being subdivided all of creation into four distinct segments that represented the four elements (earth, water, air, and fire), to which all plant and animals (both real and mythological) were linked. Earth, the lowest and least noble of these elements, was the natural element in which all plants grew, but even within this segment of the chain there was a perfectly hierarchical system at work. According to the botanical ideas of the time, the least noble plants were those that produced an edible bulb under ground (such as onions, garlic, and shallots). After these came slightly less lowly plants whose roots were eaten (turnips, carrots, and many root crops no longer in use). The next step up in the plant world was to all those plants whose leaves were eaten (spinach and cabbage, for example). At the top came fruit, the most noble product of the plant world. Fruit was considered to be very much superior to all other plant products and therefore more fit for the upper classes. The supposed nobility of fruit was due to the fact that most of it grew on bushes and trees and thus grew higher off the ground than all of the previously mentioned produce.

Moreover, plants were thought to actually digest the terrestrial food they absorbed with their roots and turn it into sap, which continued to improve as it rose in the plant and produced leaves, flowers, and, best of all, fruit. It was even thought that the taller the plants grew, the more the rising sap “digested” and transformed the cold and raw humors of the earth into something more acceptable. Even on the same tree the fruit that was higher off the ground was thought to be better than the rest. This rather mechanical application of a theory led people to think of strawberries and melons as very poor fruit, a consensus that was further confirmed by the informed opinion of dieticians.

The second segment of the Chain of Being (the segment associated with water) produced the lowly sponges that seemed more plants than anything else; nevertheless, they were considered somewhat sentient since they responded to touch. One step up from them, but still at the low end of this category, were the mussels and other shellfish that could not move on their own and seemed, because of their shells, to be partially inanimate. Higher up, and therefore more “noble” than the previous group, were the various kinds of crustaceans (such as shrimp and lobsters) that crawled on the floor of the sea. Somewhat more elevated were the various kinds of fish, even though they were distinctly overshadowed by another group of aquatic animals at the top of the category—all those animals that, like dolphins and whales, tend to swim on the surface of the water and, at times, even reach out of this element into the next highest one (air) as if they were striving upward to some kind of perfection. It might well be that these ideas about the nobility of dolphins and whales contributed to their being hunted and eaten in this period of European history more than any time after.

The third segment of the Chain of Being, the one connected with the element air, contains yet another hierarchy of values. It begins, at the bottom, with the lowest kinds of birds—those that live in water (ducks, geese, and wild birds living in or near water, such as the cormorant) and were thus thought to reveal their lowly status by being associated with that lower element. Chickens and capons were considered to be much better fare since they were more obviously aerial animals; in fact, any respectable banquet had to include such fowl. The next step up was occupied by songbirds, a very late medieval and Renaissance culinary passion, and at the top of the category were the highest-flying birds, such as the eagle and falcon. The latter were not really considered to be food but rather were kept as companions and were used primarily by the upper classes for hunting. The story in Boccaccio’s Decameron (day 5, novella 9) concerning the unrequited love of Federigo degli Alberighi reveals an interesting use of these ideas. Federigo, who has been reduced to poverty in his efforts to win over his beloved monna Giovanna, ends up living in a little farm outside Florence with his last earthly possession, a falcon whose hunting talents manage to keep him fed. Many years later Giovanna comes to see him because her son is convinced that the only thing that will cure him from his sickness is to own Federigo’s falcon. Unfortunately, the noble Federigo has no food on the day that he receives Giovanna, and, although he is in the throes of anguish, he decides that the falcon is a “degna vivanda di cotal donna” (a worthy dish for such a woman). The pathos of the story is developed around the idea that the falcon is both a companion and a noble food and that Federigo has no other choice than to transform him from a faithful companion into a dish for his beloved.

The Great Chain of Being, as it was understood in the late Middle Ages and during the Renaissance, did not manage, like most general theories, to account for everything. One of its main problems was to classify quadrupeds since they were hard to assign to any element in particular. While they obviously were earthbound, they could hardly be considered in the same way as plants. On the other hand, quadrupeds could not be linked to the element air and thus compared to birds. In practice they were not introduced in the general scheme. However, these animals can be inserted somewhere in the middle of the chain: they were considered, quite obviously, nobler fare than what the plant world produced and yet less prized than fowl.

The meat of quadrupeds, like everything else, was ordered in a strict hierarchy. At the very top was veal, always the most expensive meat on the market, and second only to fowl. At banquets, such as the one that was held in honor of the marriage of Nannina de’ Medici to Bernardo Rucellai in 1466, veal was given to the people who came from the country properties of these two families, whereas the most important guests were served capons, chickens, and other fowl. In the hierarchy of meats, mutton (very much the everyday fare of the merchant classes) was placed below veal, and pork occupied the lowest rank. The latter was looked down upon, especially when salted, probably because it was also the meat that was most available for the lower classes.

The hierarchical structure of both society and nature suggested that these two worlds mirrored or paralleled each other. As a consequence, it was believed that society had a “natural” order whereas nature had a kind of “social” order. One of the outcomes of this parallelism between the natural and the social worlds was the general view that the upper strata of society were destined to eat the foods belonging to the upper reaches of the realm of nature. In fact, the idea that the produce of nature was not all the same (since it was hierarchically ordered) and that specific foodstuffs were associated with specific sectors of society became increasingly plausible. It seemed to make perfect sense that fowl be considered the food, par excellence, for the rich and mighty of the earth who, it was thought, needed to eat birds precisely to keep their intelligence and sensibility more alert as the previously quoted Thierriat would have had it. Doctors like the Bolognese Baldassare Pisanelli, whose treatise on diet was first published in 1583, could say without a hint of irony, “Le pernici non nuocono se non a gente rustica” (Partridges are only unhealthy for country people). They also pointed out that fowl was suited to the upper classes whereas the meat of quadrupeds, which was, according to the ideas of the times, heavier and more substantial, seemed more suitable for the merchant classes since their type of life called for somewhat more sustenance. Pork and old animals in general (sheep, goats, and oxen) that were no longer useful otherwise provided the meat for the lower classes that needed yet more sustenance.

The working classes might have been destined some meat, but they were considered best off eating vast amounts of vegetables. There is no doubt, of course, that vegetables had a prominent part in the poor man’s diet in western Europe from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century, primarily for economic reasons. In fact, vegetable gardens all over Europe produced relatively cheap and abundant quantities of edibles. However, this kind of diet was also invested with a strong class bias that surfaces in all kinds of documents. The link between vegetables and the lower social orders is always very evident to the extent that it sometimes constituted a quasi-symbiotic relationship. Doctors, dieticians, and the authors of novelle are often guilty of a significant inversion when they affirm that the great quantities of vegetables eaten by the poor are the result of a physiological necessity rather than a diet imposed on them for economic reasons. A well-known example of this is to be found in the late-sixteenth-century tale of Bertoldo by the Bolognese author Giulio Cesare Croce. In this story, a peasant from the mountains, accustomed to eating turnips and other lowly food, is adopted by a king and lives at his court. As time passes, the peasant Bertoldo becomes increasingly sick; since the doctors do not know his social origins, they give him the wrong remedies. Bertoldo, who knows what is really wrong and the remedy required, asks for nothing more than some turnips cooked in the ashes of the fire and some fava beans (also associated with the diet of the peasantry). Unfortunately, nobody sees fit to provide him with this simple fare and he finally dies a miserable death. The ironic epitaph on his tomb reminds everyone that “He who is used to turnips must not eat meat pies.”

The Great Chain of Being can thus be said to have had a double function. On the one hand, it ordered and classified the natural world in ways that could be understood; on the other hand, it provided a social value for all the foodstuffs used by man. This double function of classifying and evaluating created a code that could be used to communicate social differences in a subtle way. Every foodstuff had a specific connotation, and even the diets prescribed by doctors respected social differences as one of the most important variables. As a consequence, all foodstuffs were invested with an outward and apparent value, very much like clothing, that communicated social differences. Little wonder that sumptuary laws give so much attention to what was served on everybody’s plate, as if it were possible to calculate an exact equivalence between different dishes while staying within the limits of what was still considered an acceptable display of luxury. In Florence, for example (but one could look elsewhere and find the same phenomenon), a city statute passed in 1415 specified that the course of roasted meats served at wedding banquets could consist of only one capon and a meat pie on each trencher. However, it was also possible to serve a duck and a pie, or two partridges and a pie, or two chickens and a pigeon, or two pigeons and a chicken, or a duck and two pigeons, or even just two chickens. These laws and their obsessive attention to details tried to anticipate all the possible combinations and permutations of an alimentary system that was highly codified. However, just as the lawmakers did not manage to foresee new inventions that allowed people to circumvent the rules in the realm of clothing, so did organizers of banquets seem to find loopholes in the laws. In the end, food and social differences were too deeply rooted in a society where even a subsistence diet was anything but ensured.