Jean-Louis Flandrin

The medieval cuisines of western Europe, insofar as we are able to reconstruct them from surviving cookbooks, share certain common characteristics that clearly differentiate them from the European cuisines of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. By contrast, it is hard to imagine what common features (other than those linked to modern food-processing technologies) might characterize the latter in relation to the cuisines of other periods or other continents.

Clearly, the modernization of cooking was not a simple process whose broad outlines can be spelled out for the continent as a whole. Its history must be written country by country, but given the current state of research, this is unfortunately not yet possible. In Europe, national cooking styles diverged between the end of the Middle Ages and the middle of the nineteenth century, at which point the development of large-scale industry began to reverse the process, not only in Europe but to some extent throughout the world.

In this chapter, which is devoted to the cuisine of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, I have therefore chosen a two-pronged approach. I will focus first on the culinary art of one European country—namely, France, not only because its history is for the time being better known than that of other countries but also because its cuisine was the dominant cuisine in Europe during the period in question. I will then examine the differences between French taste and the tastes of other countries and try to determine to what extent those differences were rooted in ancient traditions or had more recent origins or were simply the result of discrepancies in the pace of modernization.

French-Style Modernization

In France modernity of taste manifested itself in both the choice of ingredients and the manner of their preparation. To be sure, changes could easily go unnoticed, since meat dishes still dominated the better tables while the diet of humbler people was mainly based on vegetable matter (in the form of bread and soup). Beyond this apparent stability, however, important and complex changes were taking place.

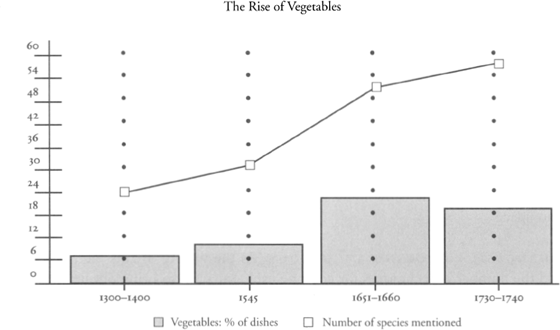

A NEW TASTE FOR VEGETABLES In the second half of the sixteenth century and throughout the following century, the number of vegetable dishes mentioned in cookbooks increased sharply, as shown in the graph opposite. In the eighteenth century, the rate of increase slowed, but the number of species mentioned continued to increase—from twenty-four in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries to twenty-nine in the sixteenth to fifty-one in the seventeenth and fifty-seven in the eighteenth.

Within this overall category, the prominence of three families of vegetables increased more than the average: mushrooms, artichokes and cardoons, and asparagus and other tender shoots. Cookbooks did not begin to record the success of these vegetables until after 1651, but other evidence, such as treatises on dietetics, suggests that it was already considerable in the second half of the sixteenth century.

By contrast, starchy vegetables declined steadily in relation not simply to other vegetables but also, in the case of cereals, to other foods generally. Whereas in the Middle Ages the social elites had sought the most nourishing plants, from the sixteenth century on they favored less nourishing ones, as if their goal were no longer simply to survive but rather to introduce greater diversity into cooking and indulge their appetites.

FOWL AND MEAT The one innovation in meat-eating that historians usually mention is the introduction of the turkey in the first half of the sixteenth century. This bird, imported originally from America, is mentioned with increasing frequency in cookbooks, and the fact that its price was falling suggests that it was eaten by growing numbers of people, despite which it maintained its gastronomic status. But two other changes not related to the discovery of America tell us more about the dominant trends in European taste.

First, the number of animal species served on the better tables decreased (while the number of plant species increased). Between 1500 and 1650, cormorant, stork, swan, crane, bittern, spoonbill, heron, and peacock—large birds once featured at aristocratic feasts but deemed inedible today—vanished from cookbooks and markets. So did marine mammals and their by-products, ranging from whale blubber, once considered indispensable during Lent, to porpoise and seal. Of the amphibious species classified as “fish” by the church, only the scoter, a kind of diving duck that no one eats today, survived as a dish for meatless days until the end of the eighteenth century.

Archaeological investigation of animal remains has confirmed this narrowing of the range of edible species with respect to both fish and birds. At the monastery of La Charité-sur-Loire, for example, monks in the eleventh century had eaten dozens of species of fish, but by the seventeenth century they had lost all taste for species other than the carp they raised in their hatchery. Historians have concluded from this and other evidence that diet ceased to be determined by the hazards of production and began to be shaped instead by consumer preferences.

This interpretation is supported, insofar as the social elites are concerned, by kitchen accounts and butchers’ ledgers. As early as the fourteenth or fifteenth century, cooks in aristocratic households turned up their noses at goats and sheep (male or female). They did on occasion serve the meat of cows (equivalent in status to steer meat) and specific parts of the animal such as the udder, as well as the meat of the kid, which was recommended by dietitians. Both of the latter meats vanished from princely tables and cookbooks in the first half of the eighteenth century. By the end of the century, the kid was still prized in only a few provinces, as we know from the schedule of price ceilings imposed by the Revolution. As for cow meat, its exclusion was the counterpart of the gastronomic rehabilitation of steer beef, which had been less costly than veal and mutton in the sixteenth and early seventeenth century but overtook these in 1639.

As the status of beef rose, so did the proportion of butcher products generally relative to other types of animal flesh in cookbook recipes. Much more attention was paid, moreover, to the particular cut of meat. With the exception of Le Ménagier de Paris (1493), fourteenth- and fifteenth-century cookbooks had usually been content simply to call for beef, veal, and so forth without indicating any specific cut. It was in the early modern period that specifying the cut became commonplace.

CHANGES IN COOKING TECHNIQUE As the variety of cuts increased, so did the number of techniques for cooking each one so as to bring out its distinctive characteristics. Take beef, which in the Middle Ages had been considered “crude” and dismissed as indigestible. Chefs in the aristocratic kitchens of the period made little use of beef other than in bouillons, stews, and pâtés. For roasting and even for serving with sauce they preferred the more “delicate” meat of fowl or of smaller mammals such as rabbit, hare, mutton, and veal. Only Le Ménagier de Paris, a bourgeois cookbook, concerned itself with the specific qualities of different cuts of beef, some of which it recommended for roasting.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, cooks used beef to make not only soup but also stock and gravy, which required roasting the beef in order to collect its juices. They also began roasting sirloin, fillet, and rump steak and serving them in their own juices. And they grilled steak and ribs. Sometimes the meat was cooked first in sauce and then grilled in buttered paper (en papillote) to promote complete absorption. Sirloin, fillet, hip, rump, oxtail, tongue, kidneys, brains, tripe, and eyes were also braised in a sort of court-bouillon. Slices of top round or rump larded with fat and marinated in white wine might also be baked in a sealed terrine. Cooks raised the status of the lowly stew by preparing stews with nothing but meat from the rump or breast of the animal. Stews could be reheated with onions to make miroton, just as roasts had been reheated in the past and served as galimafré. Oxtail was braised in a sauce of wine and onions or marinated, breaded, and grilled “à la sainte menehoult,” as this technique was known. The steer’s palate was marinated and fried either in rings or croquettes. Tongue was served en paupiettes (wrapped around a filling) and au gratin (topped with grated breadcrumbs and butter) or else braised and then roasted on a spit and served with sauce.

Thus, like their medieval predecessors, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French chefs often subjected meat to two successive types of cooking. They tried harder, however, to preserve the natural flavor of the ingredients. Before putting meat on the spit for roasting, both Taillevent’s Le Viandier and Le Ménagier de Paris had generally recommended “parboiling” in water in order to firm up the meat in preparation for larding. But by 1651 La Varenne was recommending “blanching over the fire” for the same purpose so as not to dilute the meat’s natural juices.

When the preliminary cooking was done in liquid, cooks were more careful about quantities. Many recommended braising or cooking in a court-bouillon, in some cases adding that the amount of liquid to be used “should be just enough to moisten the meat,” as in the recipe for braised beef tongue in La Cuisinière bourgeoise. Sometimes the goal was to get the meat to reabsorb all the juice it had lost while being cooked in the bouillon. In cooking ribs, for example, cooks were admonished to “reduce the sauce so that all of it sticks to the rib” and then to condense it still further by grilling en papillote.

Unlike medieval chefs, who often boiled previously roasted meats in highly spiced sauces so as to impregnate the flesh thoroughly with the flavor of the sauce, cooks in later centuries avoided this technique for a variety of reasons. According to Le Cuisinier français, for example, sirloin fillets should first be roasted, then sliced, and “simmered uncovered” for a time brief enough not to darken the meat. Similarly, La Cuisinière bourgeoise recommended heating the meat in its sauce “without boiling” so as not to toughen its texture. But others, like the purist author of L’Art de bien traiter, rejected these methods, preferring instead to roast the meat on a spit and serve it rather rare in its own juices.

Fowl were also roasted on a spit and dressed with sauce only on the serving plate. Furthermore, the sauce was ladled onto the plate itself rather than over the meat. In addition to preserving natural flavors by browning the meat, cooks tried to harmonize flavors by wrapping the meat in strips of bacon or buttered paper to protect it from the heat during cooking. There was even concern to preserve natural component flavors even in stews, including the old haricot de mouton. La Cuisinière bourgeoise gave not only the usual recipe but also a second recipe for haricot de mouton distingué, a more delicate preparation, in which the cutlets and turnips were cooked separately and combined only on the serving plate.

In addition to new cooking techniques, early modern chefs also invented new ways of making sauces. They often used a liaison made of thickened almond milk or egg yolks whipped with cider vinegar, both of which were known in the Middle Ages. But they also developed the butter liaison, which they used to make white sauce, the equivalent of the modern beurre blanc. For meat sauces and stews they preferred roux (or “fried flour,” as it was called at the time), which almost completely supplanted the old method of thickening sauce with bread. The roux technique, much decried nowadays, was at the time a widely applauded innovation that made it possible to make much smoother thickened sauces than in the past.

CHANGES IN SEASONING The most dramatic changes concern seasoning, and here we have evidence that what took place was nothing less than a mutation of taste. The “strong flavors” of the Middle Ages—sour and spicy—still had some adherents, but increasingly the social elite rejected them in favor of sauces made with fat. This resulted in dishes that many people considered to be subtler and more “delicate” while better preserving the “natural” taste of their ingredients. Although people continued to cook with spices and vinegar in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, they used much less of these strong seasonings than in the past and much more butter and cream, together with the natural juices obtained from cooking meat (sometimes reduced by boiling).

Spices still figured in 60 to 70 percent of all recipes, however, a proportion just as high as in the Middle Ages. But two changes are worth noting. First, the number of spices in common use had diminished considerably: long gone were galingale, grains of paradise, mace, “spicnard” (spikenard), cardamom, anise, cumin, mastic, and the long pepper, while cinnamon, ginger, and saffron were rarely used. Cinnamon was increasingly associated with sweets and ginger with charcuterie. The only spices that continued in regular use were pepper, cloves, and nutmeg, and these were much more widely used than before.

They were also used more sparingly. This statement is difficult to prove on the basis of cookbooks alone because recipes were still imprecise. From them, however, we do learn that cloves were no longer stuck into limes or (as is still done nowadays) onions. And in addition to cookbooks we have the reports of French travelers, who complained of foreign cooking so spicy that, no matter how hungry they were, they could not eat what they were served. Such complaints, which do not appear until the middle of the seventeenth century, attest to a change of Gallic sensibilities in this regard.

Acidic ingredients were somewhat more diverse than in the Middle Ages: bigarade (the juice of the Seville orange) and lemon juice were added to white wine, wine vinegar, and cider vinegar. In medieval sauces, which were made without oil or butter, vinegar or cider was often the only liquid component, and the bread used for thickening did little to moderate the acid’s bite. This accounted for the characteristic taste of the so-called green sauce generally made of toasted bread, vinegar, and herbs, as well as the “sauce for capon or hen,” described in Le Ménagier de Paris, which consisted of “four parts of cider vinegar and a fifth part, no more, of fat from the hen or capon.” By contrast, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the acidic component was reduced. For example, the white sauce described in L’Art de bien traiter contained just a teaspoon of a court-bouillon prepared from one part vinegar and one part water thickened with a much greater quantity of butter. The same was true of the “piquant sauce” in La Cuisinière bourgeoise, where “piquant” meant not spicy but acidic: the recipe called for two large onions, a carrot, a parsnip, and various herbs browned in butter. To thicken the sauce, one added a pinch of flour moistened in stock together with a teaspoon of vinegar. Then the mixture was simmered over a low flame, which further reduced its acidity.

Unlike medieval sauce recipes, which never mention either butter or oil, the sauce recipes of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries used these ingredients almost as frequently as we do today. Butter, which was used on lean as well as fat days, had not yet totally supplanted olive oil in aristocratic and bourgeois kitchens, much less bacon, lard, and other animal fats. It was not until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that butter-based sauces became the characteristic feature of French haute cuisine, in contrast to popular and regional cuisines still based on animal fats and olive oil. In many recipes from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, moreover, butter was mixed with bacon or olive oil.

Another major change had to do with the use of sugar and with attitudes toward sweet dishes. Sugar consumption increased dramatically in France and other European countries between the beginning of the sixteenth century and the end of the eighteenth. If we look at the proportion of sweet dishes in cookbooks of the period, however, we find that it began to decline in the seventeenth century.

In the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries, sugar figured at different points in the meal: in soups, appetizers, and roasted meats as well as in side dishes and desserts. Starting in the seventeenth century, however, it became increasingly common to relegate all sweet dishes to the end of dinner as well as to lunches and snacks that were consumed with sweetened beverages. In meat and fish courses sugar was not used as often as in the past, but it became more common with cakes and other flour-based confections as well as in creams and custards based on milk, butter, and eggs and in lemonades and other new drinks. Like fruits and some pastries, these were prepared by the butler in his pantry and not by the cook.

In the sixteenth century the appearance of a new type of technical literature, the treatise on making preserves, surely owed a great deal to the increase in sugar consumption. No doubt this also contributed to the growing lack of interest in sugar on the part of cookbook authors, who exemplified the modern tendency to specialize. But, more than that, there was an ever more prevalent feeling that sugar was not compatible with meat, fish, and most vegetables, as the opposition between sweets and savories continued to develop.

Other Tastes, Other Cusines

Taken together, these changes in taste and culinary practice define the French pattern of modernization. They did not occur to the same degree throughout the country, however. And in other countries we find even less evidence of them, as travelers’ reports amply confirm.

TOO SWEET OR TOO SPICY In 1630 Jean-Jacques Bouchard had this to say about Provence: “Food is prepared in the Italian style, with abundant spices and extravagant, strongly flavored sauces, and as in Italy [they also make] numerous sweet sauces with Corinthian grapes, raisins, prunes, apples, pears, and sugar.” This report tells us a great deal about the chronology of changes in French taste, the distinctiveness of the gastronomy and cuisine of Provence as compared with the Paris region, and French perceptions of Italian culinary practices.

Nevertheless, Italian culinary treatises of the baroque period attest to an evolution similar to that which took place in France in regard to spices. In the sixteenth century Messibugo used spices in more than 82 percent of his recipes: cinnamon, saffron, pepper, ginger, cloves, nutmeg, mace, and coriander. And Giovanni Del Turco used spices in 71 percent of the recipes in his Epulario. Like the French chefs of the seventeenth century, however, his palette was reduced: he used only pepper, cinnamon, cloves, and saffron, and there is no evidence that the quantities employed were larger than before. The main difference was that he used no nutmeg, whereas cinnamon was ubiquitous—and invariably combined with pasta.

The Spanish were also reputed to like their food spicier and sweeter than other nationalities. A seventeenth-century English traveler by the name of Willoughby noted that they “delight in pimiento and Guinea pepper and include them in all their sauces.” And at the end of the eighteenth century, if the Marquis de Langle can be believed, the nobles of Aragon were still fond of garlic and pimiento—a “fruit as long as one’s finger…[and] which tastes like pepper” and “leaves your mouth burning and your breath on fire for the rest of the day.”

In 1691 Countess d’Aulnoy visited Spain and immediately complained about the grand supper served her for St. Sebastian’s Day, which was “so full of garlic and saffron and spices” that she couldn’t eat any of it. She also disliked the “very nasty stews, full of garlic and pepper,” and a “pastry [which] is so peppery that it burns your mouth.” At a dinner with the queen mother in Toledo, she found herself “like Tantalus, dying of hunger but unable to eat a thing. For there is no middle ground between meats reeking of perfume,” and therefore disgusting, and those “full of saffron, garlic, onion, pepper, and spices,” and therefore impossible to eat. The excessive sweetness of Spanish food was due not only to the craze for flavoring dishes with amber, which the countess also detested, but also for the incongruous use of sugar. The countess complained, for example, of a ham that was served to her in Madrid, which would have been excellent had it not been “covered with candies of the sort that we in France call nonpareils…whose sugar melted into the fat.” To make matters worse, the meat was “larded with lemon rind, which considerably reduced its quality.”

In 1675 Jouvin de Rochefort expressed his astonishment and annoyance at the fact that in Flanders and Ireland he was served sugared salads. In Ireland he sampled a salad that was “covered with a quantity of sugar equivalent to the snow cover on Mount Aetna” and claimed that “it is impossible for anyone who has never encountered such a thing before to eat it.”

In southern Germany in 1580 Montaigne was surprised to find meat accompanied by fruit. In the inns of Basel he saw “pears cooked together with the roast.” And in Lindau he declared “alien to our customs” the practice of serving “soups topped with rounds of cooked quince or apple.” In Stuttgart in 1657 Coulanges was also struck by “the many unusual stews, such as gosling stuffed with cooked apples and prunes” as well as by the “black and scrawny pieces of meat dried and peppered in the local manner” and “buttered chickens festooned with cloves.”

In northern Germany and Poland in 1648, Laboureur found much to criticize in the use of spices as he passed through Oldenburg, Bremen, and Danzig. But Gaspard d’Hauteville, who lived in Poland during the next twenty years, was just as struck by the use of sugar and fruit with meat. “Their sauces are very different from the French,” he explained. They made “yellow ones with saffron, white ones with cream, gray ones with onion, and black ones with plums,” and “they add lots of sugar, pepper, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, olives, capers, and raisins.”

In short, from the Mediterranean to the North Sea and the Baltic, French travelers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were struck by both the abuse of spices and the incongruous use of sugar and fruit garnishes with meat.

TOO MUCH SALT The chefs of central and eastern Europe evidently used more salt than the French. This is hard to imagine, given the fact that in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries French salt consumption was much greater than it is today: seven and a half pounds per person per year at the end of the eighteenth century in regions where the salt tax known as the grande gabelle was collected (and this does not include salt used for salting meat and fish) and, according to estimates by the Ferme Générale, from twelve and a half to twenty pounds per year in other regions, compared with just under five pounds today. Nevertheless, there is reason to believe that Germans and others liked their food even saltier.

With the Poles the case is clear: we have the testimony not only of a Frenchman, Beauplan, who lived in Poland in 1630 and again in 1651, but also of a German, Ulryk Wedum, who visited in 1632. According to Wedum, “No other nation uses as much salt and spices of every sort as the Poles. Because food is already salted in the kitchen, they don’t even put salt cellars on the table.”

The evidence concerning Germany is less direct, but it suggests that the Germans, too, were accustomed to eating their food saltier than the French. In any case, the social elite in France certainly consumed a much smaller quantity of salted foods. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, a German by the name of Nemeitz alerted his compatriots to the fact that Parisians did not eat meats and vegetables preserved in salt. He admitted that “people of quality sometimes have slices of Mainz or Bayonne ham on their tables,” but went on to say that “they treat these things as a great delicacy and merely sample them.”

If Jouvin de Rochefort is to be believed, the Flemish also abused salt. He complained that at the Cheval-Blanc Inn in Condé he was served “a small duck which they had cooked in vinegar and in so great a quantity of salt and pepper that it was impossible for me to eat. This is done deliberately in Flemish fortress towns and other cities, because in this way they can store large quantities of food, which they cook in ovens in huge pots several times over so as to preserve the contents throughout the year.”

In addition to salted meats, the Flemish, Germans, and Poles also ate sauerkraut and other vegetables preserved in salt. Because of the harsh northern winters, fresh vegetables were not always available in these countries. Salted vegetables were a solution to this problem, as Montaigne observed when he visited Konstanz in 1580: “They have plenty of cabbage, which they chop finely with an instrument designed expressly for the purpose. And thus chopped, they put large amounts of it into barrels filled with salt, from which they make soup throughout the winter.” When he reached Augsburg, he noted that “throughout this part of the world they chop up radishes and turnips with as much care and urgency as we thresh wheat. Seven or eight men, armed with huge knives, carefully hack away at the vats…which are used to make salt preserves for the winter, as with cabbage. With those two fruits [sic] they fill not their gardens but their fields, and they harvest them.”

According to the German traveler Joseph Kausch, the same salted vegetables were eaten in Poland, including the eastern reaches of the country, now part of Belorussia and the Ukraine. And Antonio de Beatis, who visited the Low Countries in 1516, had this to say: “Throughout Flanders, there are quantities of cabbage…. As in Germany, large amounts are stored and preserved in salt. And in winter, when the ground is covered with snow, they eat this cabbage seasoned in a variety of ways.”

NATIONAL TEMPERAMENTS Building on these reports, let us try to understand the pattern underlying these apparent differences. It was out of necessity that the Flemish, Dutch, Germans, and Poles ate so much food preserved with salt. But from this habit did they perhaps acquire a taste for salty dishes? In support of this hypothesis we have the observation of Jean Le Laboureur, who claimed that at one Oldenburg banquet, “nothing was edible except the fresh eggs,” not only because the pâtés were too spicy but also because “the other dishes were also seasoned with large amounts of salt.” But only the French saw it this way: “The Polish ambassadors ate more heartily than anyone else, because Polish stews are the same…as we have since discovered.” It was the same in Bremen: “Only the Poles ate to their hearts’ content, vociferously lauding the plentiful amounts of spice and saffron and salt that the cooks had so lavishly laid on.” Therefore, it was not only because the Poles were forced to eat preserved meats and vegetables that they consumed so much salt but also because they liked the taste, so that their chefs salted their dishes much more heavily than French chefs did.

Concerning a preserved duck that he was served in Flanders, Jouvin de Rochefort observed that it was “tasty, to tell the truth, but you couldn’t eat much without succumbing to thirst.” Thus there may have been a connection between the northern and eastern European taste for salt and the concomitant reputation for drunkenness. But did people drink too much because they ate too much salt, or was it the other way around? When Germans drank, they always served slices of bread sprinkled with salt and spices to stimulate their thirst, as both Montaigne (1580) and Misson (1688) observed at various points in their travels.

What is the key to understanding all this variety? Today we are apt to focus on the fact that the salt-loving tipplers of northern Europe were beer drinkers. But in the past the French and other wine drinkers were well versed in the art of stimulating thirst with salty snacks, as we know from Rabelais and many others. What is more, the wines of the past were generally much weaker than today’s wines, and people customarily diluted them further with water, so what French people drank regularly was as watery as German beer.

So we have to look for other keys to explain the eating and drinking habits of the peoples of northern and eastern Europe in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. Because the climate in the north was cold, people needed drinks that warmed them up. What struck contemporary observers was not that they drank beer but that they drank their wine undiluted, in excessive quantities, and also liked to get drunk on spirits made from grain.

Another possibility is that in the dry, cold, northern climate, it was believed that people tended to have “melancholy” and “earthy” (or “crude”) temperaments. Hence they were drawn to “crude” foods. With this in mind, we can understand Neimetz’s advice to his fellow Germans: “People who are accustomed to crude meats will be unable to find their fill in Paris, for there nobody eats chitterlings or salted or smoked meat or sauerkraut or rye bread or anything of the sort. Such fare is unfit for a French stomach. The Frenchman’s bread is white, and all his meat is fresh.” Of course, “crude” is a rather harsh word that people do not ordinarily apply to themselves; when a German or an Englishman alluded to the “delicacy” of the French, it was not without irony.

COOKING MEAT The English were very fond of their “crude meats,” especially beef. They were apt to judge a country’s gastronomic level by the quality of its beef, whereas the French and Italians were more likely to judge by the quality of the bread. The Englishman Townsend voiced his astonishment at the fact that in Spain beef was less expensive than mutton, a fact that would scarcely have surprised a Frenchman or an Italian.

Although the student of French markets and culinary treatises is aware that the status of beef rose in France during the early modern period, foreign visitors were not struck by this fact. To the English, in particular, the French remained chicken eaters with no idea of how meat ought to be cooked. In 1740 Horace Walpole complained of being able to find nothing but boiled beef in France. And in 1766 Tobias Smollett remarked that French beef was “neither fatty nor chewy but very good for soup, which is the only use the French make of it.”

In 1656 Peter Heylin wrote that he “had heard a lot about the skill of French chefs, but they must not exercise their talent on beef or mutton.” He criticized them for roasting pieces that were carved too small, which on the one hand was a mark of stinginess and on the other hand made it impossible to roast the meat properly. Conversely, when François de La Rochefoucauld visited England in 1785, he noted that the roasts served on the better tables “weigh twenty or thirty pounds.” In The Art of Cookery Hannah Glass indicated cooking times for roasts of ten pounds (an hour and a half over a good fire), twenty pounds (three hours if the piece is thick, two and a half hours if thin), “and so forth.”

In 1596 the Italian Francesco d’Ierni was also struck by Parisian meat-cutting practices: the city’s butchers sold meat “not by weight but by the slice.” His report should be compared with Heylin’s and with the earlier discussion about the increasing variety of cuts and the adaptation of cooking techniques to the new variety. The trend toward smaller cuts, which actually reflected progress in the arts of butchery and cooking in this period, was evidently misunderstood by people from other countries.

As for cooking techniques, Peter Heylin also accused the French of placing roasts on a spit perpendicular to the fire, rotating the spit just three times and bringing the meat to the table “more grilled than roasted.” Did he mean by this that it was raw on the inside and charred on the outside, as one would expect from such a technique? Perhaps, but his compatriot John Ray used the same phrase to describe a dried-out roast: “In Italy and other warm countries, meat is not only served leaner and drier than we serve ours but is also roasted until it is ready to drop from the bone and no juice remains. When they roast meat, moreover, they place the coals beneath the spit and allow the grease to fall onto them….Their method of roasting is not very different from grilling or charring. I am speaking of ordinary inns and the homes of common people. In the great houses, things are different.”

Arthur Young, a great admirer of French cooking, was nevertheless upset that the French “roast everything far too long.” But if the tastes of the two nations were so different in this regard, why did French travelers not make the opposite complaint about the English? Why did they leave that chore to the Spaniard Antonio Ponz and the German Neimetz? The matter is all the more puzzling in that other Englishmen felt the French did not roast their meat long enough. Smollett, for example, complained that warblers, thrush, and other small birds were “always served half-raw” in the region between Lyons and Montpellier. The French “would rather eat them that way than run the risk of losing some of the juice by overcooking,” he explained. He made a similar observation about the cooking in Nice, a city that struck him as virtually Italian. Perhaps the way to reconcile Smollett’s comments with those of Young and Heylin is to say that in every country rare cooking is reserved for the meats people truly like, while everything else is overcooked.

All observers agreed that in France meat and fowl were larded with fat before roasting. Travelers’ accounts do not tell us anything about French cooking techniques that we do not know from other sources, but they do suggest that larding was a relatively rare practice in other countries. Other evidence corroborates this: in the seventeenth century Coulanges deplored the dryness of German roasts, and a French zoologist of the mid-sixteenth century criticized the Italians for failing to lard their meat. The technique is mentioned in Italian cookbooks, however. In Epulario Del Turco recommends larding all roasts, with the exception of the fatty quail, which does not need it, and the pigeon, which he recommends marinating in olive oil.

Many travelers complained about the Italians’ bad habit of boiling meat and fowl before roasting. In the early eighteenth century, for example, Father Labat railed against the innkeeper who plunged his roasting chickens into a cauldron of boiling water. And in the seventeenth century Gilbert Burnett remarked that “when it comes to meat, they are accustomed, in the inns at any rate, to boiling it before placing it on the spit, which makes the meat tender but quite insipid.” But did the Italians boil their roasts for long periods of time in order to tenderize them and get rid of the blood, or did they just dip them briefly into boiling water in order to firm up the flesh for more convenient larding? It is the latter method that we find in Epulario, as well as in French culinary treatises from the Middle Ages. In any case, the purpose of the technique is ambiguous, and it was suspected of leaching juices out of the meat, which shocked travelers from countries where it was no longer used.

The English made fun of French sauces and stews, which they said “feed not the stomach but the palate.” Fancying themselves fond of simple, straightforward, nutritious food, they would never think of eating meat in any form other than boiled or roasted. La Rochefoucauld’s observation corroborated this self-assessment: “Gravy is never used in English cooking, and stews are rare. All the dishes consist of meat either boiled or roasted.” But English cookbooks only partially support this commonplace. In the cookbook by Hannah Glasse, who can hardly be suspected of indulgence toward French cooking, we find not only forty-five boiled beef dishes and thirty-six roasts but also thirty stews, forty braised dishes, thirty-two fried dishes, and twenty-two fricassees. What is more, most of her recipes are more complicated than comparable French recipes from the same period.

ANALOGIES The influence of French cooking on the tastes of the European social elite is particularly clear when one looks at culinary treatises: in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries these were often simply translated from the French. Because of this, it is difficult today to study the cooking practices of other countries and how they changed. Yet even in the case of national cuisines that largely escaped the influence of the French (such as the cuisine of the Italian baroque, of Spain in the Golden Age, and of English cookbooks hostile to French techniques, such as that of Hannah Glass), we find some of the same changes that occurred in France.

In England, for example, cookbook authors began to include recipes for cooking vegetables, just as in France. The proportion of beef dishes also increased sharply, while that of fowl declined (rabbit and hare held steady). Unlike the French, however, the English retained their fondness for the large, handsome birds that were often the centerpieces of medieval banquets. In cookbooks published between 1591 and 1654 one still finds recipes for eagle, bittern, curlew, and swan (whose delicious flesh drew expressions of ecstasy from Samuel Pepys in the mid-seventeenth century), as well as crane, heron, gull, and peacock. Sea mammals (such as whale, dolphin, porpoise, and seal) fell from favor, but in England this shift was accompanied by a decline in the popularity of fish, which did not occur in France, Italy, or Spain.

Although the English continued, even after the Anglican schism, to observe Lent and meatless Fridays, it is well established that fish consumption in the British Isles plummeted. In fact, in an effort to halt the dramatic decline of the English fishing fleet, the authorities tried unsuccessfully to reinstate Saturday as a meatless day in 1548 and then Wednesday in 1563. It may well be that it was not religious obligation that kept fish consumption high in France and other Catholic countries. As Arthur Young observed in August 1787 after eating a supper of two delicious carp at an inn on the banks of the Charente: “If I were to pitch my tent in France, I should like to settle near a river capable of supplying fish like those. Nothing is more irritating than to look through one’s windows and see a lake, river, or ocean yet have no fish for dinner, as is frequently the case in England.” And no doubt in the rest of Great Britain as well. John Lauder, who spent a year in Poitiers in 1656, voiced his astonishment at the fact that his hosts, like “nine out of ten Frenchmen, prefer fish to meat” and “consider it more delicate in flavor.” Yet these same hosts soon realized that their guest did not care for fish and, being courteous, “no longer served it more than once a month.”

The rehabilitation of butter is as clear in the English treatises as it is in the French, but it comes later and more abruptly. The same is true of other northern countries such as Flanders and Sweden, where butter was virtually the only fat used in cooking. In these places, however, we have no proof that this was a novelty. In Italy butter is mentioned in the mid-fifteenth-century treatises of Martino and Platina, and in the seventeenth century it was commonly associated with pasta. Throughout Europe, but especially in the northern countries, the rise of butter appears to have been connected with the decline of the Roman Catholic church and its influence on eating.

By contrast, in southern Europe, where the church maintained its authority, the use of olive oil was more prominent in the early modern period than it had been in the Middle Ages. It was no longer reserved exclusively for meatless days. By the beginning of the seventeenth century in Provence, Italy, and Spain, olive oil was used for fricasseeing chicken, partridge, mutton, and other meats. It became emblematic of Mediterranean cooking and taste. Paradoxically, this shows that church regulation was less important than in the Middle Ages.

As for seasoning, most European countries turned away from the spicy cooking that had long been their preference. In this respect France seems to have led the way. But the English were also discreet in their use of seasoning, at least before Indian curries became fashionable. Indeed, Hannah Glasse’s cookbook gives us a more precise idea of the new restraint in the use of seasoning than do most French treatises. And as we saw earlier, by the beginning of the seventeenth century, Italian chefs used no greater variety of spices than did their French counterparts, despite their reputation for a free hand in this regard. As far as we can tell from the current state of research, however, chefs in countries other than France continued to make dishes that combined sweet with savory seasonings. The separation of sweet and savory may have been not so much a sign of modernization as a distinctive feature of French cuisine.