1. Chronology of the Mid Upper Palaeolithic of European Russia: Problems and prospects

Abstract

The archaeological record of the Mid Upper Palaeolithic (MUP) of Russia (c. 30,000–20,000 14C years BP) is important both intrinsically and as part of a wider European archaeological landscape. Numerous issues have meant that the archaeology has not received the attention it deserves in the West, and it is not currently possible to easily synthesise information on Russian sites with that from elsewhere in Europe. One of the biggest problems for making sense of the archaeology is that of chronology, as there is no consensus on a chronocultural scheme for this time period in Russia, and both absolute and relative dating of sites remains problematic. The archaeology of the sites of Kostenki 8 Layer 2 and Kostenki 4 are outlined to demonstrate the importance of these sites and to illustrate some of the problems that need to be overcome in order to determine an accurate chronology. There is great potential for future work to improve the understanding of these sites, and hence to illuminate broader archaeological debates related to the European MUP.

Introduction

The Upper Palaeolithic record of Russia, with its rich sites that have yielded huge lithic assemblages, dwelling-structures, mobiliary art, and burials, holds great interest for archaeologists worldwide. Its clear similarities to the contemporary archaeology of the rest of Europe mean that it is always included as part of the European Upper Palaeolithic when this is considered as a whole. However, the archaeology from this region remains relatively under-exposed in the West, and there are huge difficulties in synthesising archaeological evidence from across the continent. This has been bemoaned for many years but more than two decades after the collapse of the USSR, progress remains slow.

Geopolitical realities constituted a serious barrier to communication throughout most of the twentieth century. Although the Iron Curtain has fallen, economic barriers to co-operation remain in place, and colleagues from all parts of Europe often find it difficult to attend conferences at distant parts of the continent. The language barrier still poses major difficulties, and although Russian archaeologists increasingly publish in English and French, the vast majority of primary literature is inaccessible to the non-Russophone. The persistent differences in intellectual traditions are, perhaps, less obvious. Soviet archaeological thought diverged strongly from Western traditions (Bulkin et al. 1982; Davis 1983; Vasil’ev 2008); post-Soviet Russian archaeological thought has inherited many of the particularities of the local tradition.

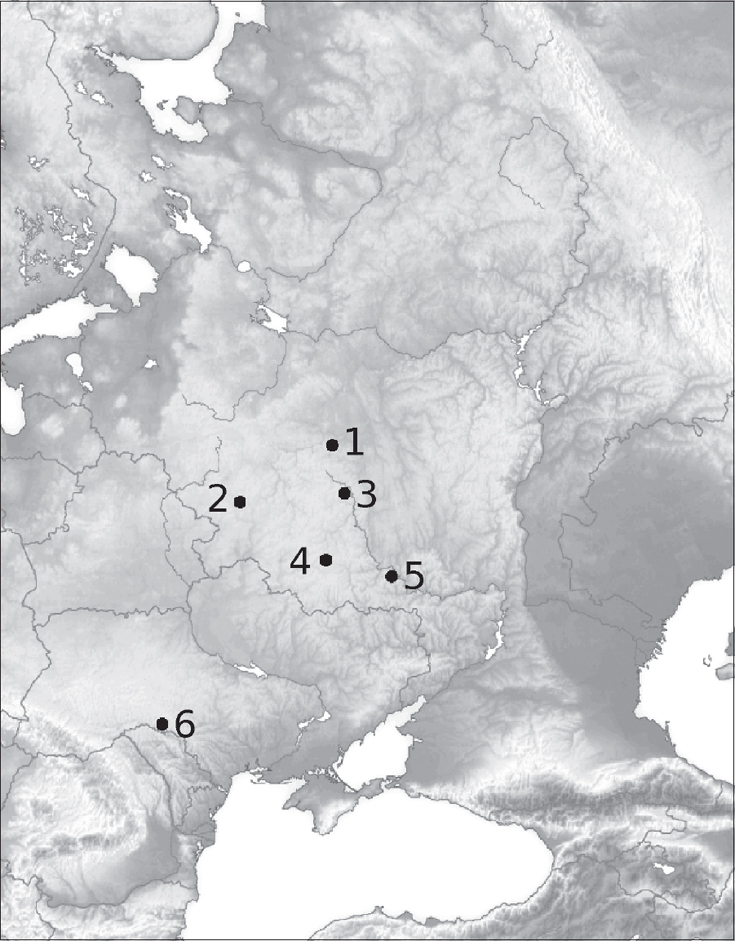

The Russian record is undoubtedly deserving of international publication and discussion. The mobiliary art and claimed existence of dwelling structures are well known worldwide; descriptions of the rest of the archaeology have had less dissemination. In combination with evidence from across Europe, the record offers an opportunity to gain an understanding of pan-European cultural processes during the Mid Upper Palaeolithic (MUP). The present article attempts to give a review of the current state of affairs in the study of this region from a western European standpoint, and to outline two major Russian MUP sites. Locations of sites discussed in the text can be found in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1. Some sites and regions mentioned in the text: 1. Zaraysk; 2. Khotylevo-2; 3. Gagarino; 4. Avdeevo; 5. The Kostenki-Borshchevo area; 6. Molodova-5.

The European MUP

The European MUP, frequently treated as synonymous with the Gravettian, dates from approximately 30,000 to 20,000 14C years BP. The period has been described as a “Golden Age” (Roebroeks et al. 2000) and has provided archaeological evidence for a broad spectrum of human activity, including textile production, ceramic production, processing of plant resources, and, more controversially, dog domestication (e.g Aranguren et al. 2007; Germonpré et al. 2012; Revedin et al. 2010; Soffer 2004; Vandiver et al. 1989).

The traditional type-fossils of the Gravette point and backed bladelet are found widely and in large numbers throughout this period; however, a great deal of temporal and regional variation is known among Gravettian industries. Industries such as the Maisierian/Fontirobertian, Pavlovian, and Noaillian, which date to this time period, are idiosyncratic and geographically and chronologically restricted, and demonstrate the technological diversity of the European MUP. They are usually (but not always) treated as sub-types within a larger Gravettian cultural and technological entity. The term ‘Gravettian’ is itself ambiguous, and may be used to describe a technocomplex or group of technocomplexes, a time period, or a perceived cultural grouping – a state of affairs which reflects the historical development of the term, as well as the perhaps under theorised nature of its usage (de la Peña Alonso 2012).

In recent years, great progress has been made in improving our chronology of, and understanding of the variability within, the Gravettian. Excellent work has been carried out on Western European lithic assemblages, often incorporating intra- and inter-site comparison (e.g. Borgia 2009; Klaric 2007; Pesesse 2006; Wierer 2013). Technological studies, for example on methods of bladelet production, are proving to be especially productive. Much attention has also been concentrated on the earliest Gravettian and the timing and nature of the Aurignacian/Gravettian boundary, with various claims across Europe for Gravettian assemblages earlier than 30,000 14C years BP (Conard and Moreau 2004; Haesaerts et al. 1996; Prat et al. 2011). The relationship between the Aurignacian and the Gravettian, if any, continues to be debated on the basis of evidence from various areas across Europe (Borgia et al. 2011; Kozłowski 2008; Moreau 2011; Pesesse 2008, 2010). Recent projects seeking to improve the radiocarbon chronology of the Upper Palaeolithic have dramatically improved our chronological framework for this time period (Higham et al. 2011, Jacobi et al. 2010).

The MUP archaeology of Russia and the Kostenki-Borschevo region

In contrast with the rest of Europe, the Mid Upper Palaeolithic of Russia is far from synonymous with the Gravettian. Rather, it is widely held that several other industries were also extant during the MUP, sometimes overlapping in time within a very small geographical region. The Gorodtsovian, Gravettian, Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture and Epigravettian are widely described (Sinitsyn 2010); other phenomena such as the “Epi-Aurignacian” (Anikovich 2005a) are also sometimes included in the Russian MUP. The majority of the evidence for the MUP of European Russia derives from the famous Kostenki-Borshchevo region, near the city of Voronezh, where twenty-six Upper Palaeolithic sites have been identified.

The Kostenki-Borshchevo sequence

The sites of the Kostenki-Borshchevo area are found along the right bank of the Don River and within a series of ravines, which open onto the river, along a distance of perhaps seven kilometres. Several river terraces have been identified above the floodplain and extend into the ravines; the Palaeolithic cultural layers were found within deposits on the first and second terraces.

On the second terrace, a series of humic layers, loessic layers, and a visible tephra deposit were found. The sequence from the base consists of a Lower Humic Bed overlain by loessic deposits and a tephra layer. These are in turn covered by an Upper Humic Bed, followed by further loessic deposits and a thinner humic layer known as the Gmelin soil, which is sealed by another series of loessic deposits, believed to date to the Last Glacial Maximum (Holliday et al. 2007). Rogachev (1957), working in the 1950s, used this stratigraphy to create a basic tripartite chronological grouping for the sites, which remains in use to this day: 1) Lower Humic Bed sites, 2) Upper Humic Bed sites, 3) sites from above the Upper Humic Bed. On the first terrace, the stratigraphy is more limited, containing only loessic deposits and the Gmelin soil. Therefore, all sites from this terrace are attributed to Rogachev’s third chronological group.

Chronostratigraphy and palaeoclimatic correlation

The part of the Kostenki geological sequence relating to the MUP (i.e. the Upper Humic Bed and above) has yet to yield precise, accurate and consistent absolute dates. However, the tephra deposit between the Upper and Lower Humic Beds has been securely identified as the Campanian Ignimbrite, dated to approximately 40,000 calendar years ago (Fedele et al. 2008; Giaccio et al. 2008; Hoffecker et al. 2008; Pyle et al. 2006; Sinitsyn 2003). At least three individual palaeosols have been identified within the Upper Humic Bed (Sedov et al. 2010). By comparison with well-studied sedimentological sections at Kurtak (Russia), Mitoc-Malu Galben (Romania) and Molodova (Ukraine) (Haesaerts et al. 2010), it is possible to suggest a tentative correlation between the Upper Humic Bed and Greenland Interstadials 8–5, and between the Gmelin soil and one, or both, of Greenland Interstadials 4 and 3. This correlation, however, is based purely on published descriptions and awaits publication of a systematic study and dating of the chronostratigraphy. Correlations between the Upper Humic Bed and the Bryansk soil (Sedov et al. 2010), and the Bryansk soil and Greenland Interstadial 8 (Simakova 2006) have previously been suggested.

Russian MUP industries

The Gravettian of Russia is defined by the presence of Gravette points/microgravettes and backed bladelets, in layers of the expected age (c. 30,000–20,000 14C years BP). The Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture, importantly, is generally treated separately, despite the presence of backed bladelets and Gravette points in sites of that industry (Gavrilov 2008; Lisitsyn 1998; Tarasov 1979). Perhaps six Kostenki sites (Kostenki 8 Layer 2, Kostenki 4 Layers 1 and 2, Kostenki 9, Borshchevo 5, Kostenki 21 Layer 3, Kostenki 11 Layer 2) relate to the Gravettian excluding the Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture (Sinitsyn 2007). Kostenki 8 Layer 2, discussed in detail below, is found in the Upper Humic Bed and has yielded a relatively early radiocarbon date of 27,700 ± 700 14C BP (GrN-10509); the other sites are all found above the Upper Humic Bed and hence belong to Rogachev’s third chronological group. Sinitsyn (2007) argues that the sites other than Kostenki 8 Layer 2 represent four faciés of the Recent Gravettian, which co-existed at Kostenki alongside the Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture. All the sites have yielded sizeable numbers of backed bladelets. Radiocarbon dates for sites other than Kostenki 8 Layer 2 range widely; however, Sinitsyn (2007), following earlier work, dates the third chronological group to 27,000 to 20,000 14C years BP.

The Gorodtsovian industry is unique to Eastern Europe and, perhaps, to the Kostenki region. The type-site for the industry is Kostenki 15 (Gorodtsovskaya), found within the Upper Humic Bed (and hence belonging to Rogachev’s second chronological group). Unusually, the type-fossil for this industry is not lithic but osseous: a number of remarkable bone “shovels” were discovered at Kostenki 15 (Rogachev 1957). The lithic assemblage from this site is relatively small, numbering about 350 retouched flint and quartzite pieces among a total collection of more than 2000 lithics. The collection includes large numbers of retouched blades and scrapers made on blade blanks, splintered pieces, and retouched flakes but, notably, no bladelets (Klein 1969; Sinitsyn 2010). There is no clear consensus on which other Kostenki sites should be attributed to the Gorodtsovian; Kostenki 14 Layer 2, Kostenki 12 Layer 1 and Kostenki 16 are often included, but there is substantial variation between researchers (Rogachev and Sinitsyn 1982; Sinitsyn 2010). The site of Talitsky in the Urals is sometimes included, and recently an assemblage from the site of Mira (Ukraine) has been attributed to it (Sinitsyn 2010; Stepanchuk et al. 1998). The available radiocarbon dates for Kostenki 15 are as follows: 25,700 ± 250 14C years BP (GIN-8020) (Chabai 2003); 21,720 ± 570 14C years BP (LE-1430) (which is inconsistent with the site’s stratigraphic position, see Rogachev and Sinitsyn 1982). Some AMS radiocarbon dates for Kostenki 14 Layer 2 range between 29,240 ± 330 (GrA-13312) and 26,700 ± 190 (GrA-10945) 14C years BP (Holliday et al. 2007). These ages overlap not only with the Gravettian elsewhere in Europe but also with the Gravettian as represented at Kostenki 8 Layer 2. It has been suggested that the Gorodtsovian sites do not represent a cultural grouping, but, rather, are a reflection of site function including kill-butchery events (Hoffecker 2011).

The Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture is found more widely than the earlier Gravettian, including at Kostenki (Kostenki 1 Layer 1, Kostenki 14 Layer 1, and Kostenki 18), Avdeevo, Zaraysk, and (more problematically) Khotylevo-2 and Gagarino (Sinitsyn 2007). Similarities with sites beyond European Russia are often stressed, as demonstrated by the technocomplex’s frequent inclusion in larger units (e.g. the Willendorf-Pavlov-Kostenki-Avdeevo cultural unity or the ‘shouldered-point horizon’ of Eastern Europe (Grigor’ev 1993; Otte and Noiret 2003; Svoboda 2007). The technocomplex is defined according to the presence of shouldered points and Kostenki knives in the lithic assemblage, female (‘Venus’) figurines, and long lines of hearths, surrounded by pits and oriented north-west to southeast. These latter features are generally interpreted as the remains of domestic structures. The majority of frequently cited dates for these sites fall between 24,000 and 21,000 14C years BP (Amirkhanov 2009; Anikovich 2005b; Gavrilov 2008; Sinitsyn 2007); at Kostenki, all relevant cultural layers are found above the Upper Humic Bed, i.e. in Rogachev’s third chronological group. The Epigravettian, not discussed here, is also represented by multiple sites at Kostenki.

Dating of assemblages

The tripartite scheme of Rogachev is certainly useful for a general relative chronology. However, the lengths of time included in each part of the scheme (probably up to ten millennia) means that it is a very low-resolution chronology. Within the second chronological group (found within the Upper Humic Bed), Aurignacian, Gravettian, Gorodtsovian and Streletskayan assemblages are all found; the third chronological group includes Gravettian, Gorodtsovian, Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture and Epigravettian assemblages (Sinitsyn 2007). Some consensus has emerged on the stratigraphical relationships, and hence chronological relationships, between these industries (e.g. the Epigravettian is later than the Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture). However, the nature of the sites, with their lack of long sequences, means that further attempts to elaborate the chronology necessitate the use of absolute – usually radiocarbon – dating.

Known problems with radiocarbon dating

It has become increasingly clear in recent years that the radiocarbon dating of periods prior to 20,000 years ago presents methodological hazards which, if not carefully avoided, can result in incorrect dates being obtained, usually younger than the true age of the samples (Higham 2011). The problems are especially caused by the presence of contaminant younger or modern carbon in samples. Thus, the adequate removal of contaminant carbon is essential to achieve reliable dating. Secure provenancing of samples is also vital. Many radiocarbon measurements taken on Palaeolithic bone and other samples over the past few decades were not processed using what we now know to be best practice for dealing with such samples. This means that many published dates must be treated with caution. Criteria have been published for evaluating the reliability of radiocarbon dates (e.g. Pettitt et al. 2003). However, for most of the dates available for Russian MUP sites, the relevant information is simply not available.

Previous use of dates in building chronology

A substantial number of radiocarbon dates have been obtained for the Kostenki-Borshchevo sites. Unfortunately, for most, if not all, layers where more than one date has been published, the dates are mutually inconsistent. For example, for the Aurignacian level of Kostenki 1 Layer 3, one publication lists thirteen radiocarbon dates, which are distributed (fairly evenly) between 20,900 ± 1,600 (GIN-4848) and 38,080 +5,460/- 3,200 (AA-5590) 14C years BP (Anikovich 2005b). Such wide distributions of radiocarbon dates – which cannot possibly reflect the actual occupation period of a site – mean that the creation of accurate radiocarbon-based chronologies of site occupations or industries is currently an impossible task. No systematic attempt has been made, as it has for Upper Palaeolithic sites on the Yenisei (Graf 2009), to assess the reliability of the published radiocarbon dates from Kostenki-Borshchevo.

Despite this, radiocarbon dates (in combination with attention to stratigraphy and Rogachev’s tripartite scheme) have often formed the basis of published attempts to understand the chronology of the region (e.g. Anikovich 2005a; Kozłowski 1986; Sinitsyn 2007), which, unfortunately, rarely agree with one another. The differences are not only due to differing uses of radiocarbon dates, but also the lack of consensus on the attribution of various sites to industries, especially in relation to the Gorodtsovian, as seen above.

Long rock shelter sequences are a boon for the archaeology of Western Europe, enabling the construction of detailed chronocultural schemes. Unfortunately, this is not a possibility for European Russia. Although there are multi-layer sites at Kostenki-Borshchevo, the individual sequences are far from complete, and may have been partly eroded or redeposited. Only better absolute dating of each assemblage will allow accurate and detailed chronologies to be created. Currently it seems that the most constructive way forward is to obtain new radiocarbon dates, using the most precise and accurate methods available. Recent results are certainly extremely promising (Douka et al. 2010; Marom et al. 2012). However, it will take time and resources – and careful attention to excavation history, stratigraphic information, and provenancing of samples – to further elaborate the chronology of the area.

Two Gravettian sites of European Russia

Although there is a reasonable amount of information published on the possible Gravettian sites of the Kostenki-Borshchevo area, the vast majority of it is in Russian. The last comprehensive English-language review of the Kostenki-Borshchevo sites was published by Klein (1969) and was itself heavily dependent on Russian literature mostly published during the 1950s. Two of the most interesting (and largest) possible Gravettian sites at Kostenki-Borshchevo are outlined below, to give an impression of the richness of the archaeology of these sites and the potential for further work. These assemblages are notably under-studied and have received limited attention in the last three decades.

Kostenki 8 (Tel’manskaya) Layer 2

Kostenki 8 (Tel’manskaya) Layer 2 is the only Kostenki assemblage found within the Upper Humic Bed (i.e. belonging to Rogachev’s second chronological group) that is attributed to the Gravettian. It is located on the second terrace above the Don. The site was discovered in 1936 and was the subject of excavations during 1937, 1949–52, 1958–59, 1962–64, 1976 and 1979 (Rogachev et al. 1982). Further, limited work has taken place in the past decade led by V. V. Popov (Bessudnov 2009).

The site contains up to five cultural layers. Layer 2 has been excavated over an area of 530 m2 (Rogachev et al. 1982). It has been claimed that the layout of hearths and accumulations of cultural remains at the site is evidence for five small circular structures, or two small circular structures and one larger one (Rogachev and Anikovich 1984). Hare and wolf predominate among the faunal remains, which also include aurochs, horse, mammoth, reindeer, woolly rhino, red deer, Megaloceros, arctic fox, cave bear, birds and fish (ibid.).

The lithic assemblage contains 22–23,000 pieces, of which c. 2,100 are retouched, including a huge number of backed pieces (c. 900, or 43% of the retouched pieces) (Rogachev et al. 1982). The assemblage has been described as Early Gravettian/Gravettien ancien (Moreau 2010; Otte and Noiret 2003; Sinitsyn 2007), Gravettoid (Anikovich 2005a), “putatively Gravettoid” (Vishnyatsky and Nehoroshev 2004), “Mediterranean-type Gravettian” (Efimenko 1953, 1956 and 1960 cited in Sinitsyn 2007) and, eponymously, “Thalmannien” (Djindjian et al. 1999). The Early Gravettian attribution is based on the radiocarbon date given below, the site’s stratigraphic location within the Upper Humic Bed, and the lithic assemblage. However, no detailed study of the lithic assemblage has yet been carried out (Moreau 2010).

Rogachev et al. (1982) have provided the most complete description so far of the assemblage, on which the following summary is based. The assemblage is heavily blade-based, with blades and bladelets forming blanks for the majority of retouched pieces. Imported flint was overwhelmingly used as a raw material and nuclei were, as a rule, worked to exhaustion. There are at least 120 blade and bladelet cores in the assemblage, including c. 100 bladelet cores on blades and flakes. Single- and opposed-platformed prismatic cores are represented. Large numbers of unretouched as well as retouched blades were found. The latter group includes burins of various types (c. 500 pieces), retouched blades, notched blades, and truncated blades. There are around 50 scrapers in total, including many made on blades. Many of the c. 900 backed bladelets and microgravettes are broken. They are all, apparently, extremely small, ranging from 1–5 cm in length and 0.1–0.5 cm in width, but usually around 3 × 0.3 cm (no data on thickness are given). Although the majority of bladelets are backed only along one edge, other varieties of retouch do exist, including complete or partial, marginal or backing retouch on the opposite edge. On some bladelets there is flat ventral retouch on one or both ends. Backing is usually direct, but may be crossing. There are small numbers of ‘trapezes’ (n=10) and ‘segments’ (n=14); these are bladelets modified with backing retouch into trapezoidal or arched shapes.

One date on charcoal of 27,700 ± 700 14C BP (GrN-10509) (Rogachev et al. 1982) remains universally cited for this assemblage. Other dates of 24,500 ± 450 14C BP (GIN-7999), 23,020 ± 320 14C BP (OxA-7109) and 21,900 ± 450 14C BP (GrA-9283) have been argued to be erroneous, as they disagree with the usual dating of the Upper Humic Bed (Sinitsyn 1999 cited in Moreau 2010).

The assemblage is widely referred to as the earliest Gravettian assemblage in Russia or, sometimes, in Eastern Europe (e.g. Anikovich 2005a; Otte and Noiret 2003; Sinitsyn 2010). Although Sinitsyn (2007) also attributes other Kostenki assemblages to the Gravettian, he stresses the uniqueness of this assemblage within Eastern Europe in the time period between 28–27,000 radiocarbon years ago. Comparisons have been drawn with sites of a similar age elsewhere in Europe. Efimenko (1953, 1956, and 1960 cited in Sinitsyn 2007) believed it was similar to the Grotta Paglicci. Moreau (2010) claims that it differs from the Swabian Early Gravettian, although the precise grounds for this are unclear. Otte and Noiret (2003) suggest an origin for the Moravian MUP at Kostenki 8 Layer 2, based on the shared presence of geometric microliths.

Kostenki 4 (Aleksandrovskaya)

Kostenki 4 is a problematic site. Found on the first terrace, it is placed in the final Kostenki chronological group of sites lying above the Upper Humic Bed. It was discovered in 1927 and further excavated in 1928, 1937–8, 1953 and 1959. In total, 922 m2 were excavated at the site (Rogachev and Anikovich 1982). Most recently, work has continued on the interpretation of the stratigraphy (Anisyutkin 2006; Zheltova 2009) and on certain aspects of the lithic assemblage (e.g. Zheltova 2011).

According to its principal excavator, Rogachev, and as repeated in reviews since, the site contained two layers, which were deposited directly one on top of the other in most areas of the site, but in others had an intermediate sterile layer. The lower layer (Layer 2) contained two lines of hearths surrounded by accumulations of finds, similar to the ‘long-houses’ of the Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture, while the upper (Layer 1) contained two small round structures. Although the finds horizons were inseparable over most of the site, the raw material and artefact typology were apparently sufficiently different in the areas where they were separated to sort part of the remaining material into collections for each layer (Klein 1969; Rogachev 1955; Rogachev and Anikovich 1982, 1984; Sinitsyn 2007). However, a recent study of the original site documentation has challenged the division of the site into two cultural layers (Zheltova 2009). It found that the layers described as sterile in fact contained finds, and states that there is no way of securely dividing the collection into two layers. Such a conclusion, if correct, perhaps sheds light on why it has been so difficult to assign the upper layer to a particular industry, as seen below.

The following summary of the Layer 1 assemblage is based on Rogachev and Anikovich (1982) where not otherwise stated. According to the published descriptions, the lithic inventory for this layer includes around 16,000 pieces of fine-grained flint (and some quartzite), including around 270 cores and 1,700 retouched pieces. Blade cores are nearly exclusively prismatic: either single-platformed, with removal of blades along the whole perimeter, or double-platformed with removals along part of the perimeter only. There were about 180 bladelet cores on large blades or flakes. Among the retouched pieces, backed bladelets form the largest group, numbering around 400. Usually one edge has straight backing retouch, while the opposite edge is curved and partly retouched at the tip. There are also around 250 burins and 75 scrapers of various types. Interestingly, there are around 190 symmetrical points on blades, with one end bearing semi-steep retouch shaping a point, and the other end worked with dihedral burin removals (Zheltova 2011). Among the remaining lithics are a bifacially-worked leaf-shaped point and shouldered point. Further information about the assemblage, including pieces believed to have been used as pestles or grinding stones, the mobiliary art, and the osseous industry, is available in Klein’s (1969) synopsis.

The collection from Layer 2 numbers around 60,000 pieces, including about 250 cores and 7,000 retouched pieces. The blade cores are similar to those described above for Layer 1 (Rogachev and Anikovich 1982). There are around 2,600 backed pieces, which Rogachev and Anikovich (1984) divide into two groups. The first consists of subrectangular backed bladelets sometimes with one or both ends also backed, either straight across or in the form of a notch. The unbacked long edge may be either unworked, with limited retouch towards the ends, or denticulated. Their second group is made up of points, bladelets with backing forming a point at one end. There are about 1,200 splintered pieces, 150 burins and 220 scrapers. The osseous industry includes awls and polishers, and there are pierced teeth of arctic fox and wolf, and perforated mollusc shells (Rogachev and Anikovich 1984).

The available radiocarbon dates for the site currently place it late in the MUP, which agrees with its placement in Rogachev’s final chronological group based on its stratigraphic position. They are: 20,290 ± 150 14C BP (OxA-8310) (Layer not stated) (Bronk Ramsey et al. 2002); 22,800 ± 120 14C BP (GIN-7995) (Layer 1) (Djindjian et al. 1999); 23,000 ± 300 14C BP (GIN-7994) (Layer 1) (ibid.)

The Layer 1 assemblage has been described as Gravettian (Djindjian et al. 1999), Gorodtsovian (Efimenko 1956, 1958 cited in Sinitsyn 2010), Solutrean (Rogachev 1955) and Aurignacoid (Anikovich 2005a; Anisyutkin 2006), while it has also been said that there are no analogous sites anywhere on the Russian Plain (Rogachev and Anikovich 1984). The animal figurines have been found to be similar or near-identical to those from Kostenki 11 Layer II, although the strong dissimilarity of other aspects of the material culture has also been noted (Rogachev and Anikovich 1984; Sinitsyn 2007). The assemblage from Layer 2 is usually described as Gravettian by Russian authors (Sinitsyn 2007; Zheltova 2009), though the long lines of hearths surrounded by accumulations of artefacts are very comparable to those of the Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture (Djindjian et al. 1999).

Incorporation of the Russian record into a European framework

The assemblages outlined above demonstrate some of the variability of the archaeological record just among Gravettian collections; the additional presence of Gorodtsovian, Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture and Epigravettian assemblages must not be forgotten. There are clearly significant differences even just between the groups of backed bladelets found at Kostenki 8–2 and 4–2, which is no surprise given the apparently large difference in age between them. Published descriptions of the other Russian probable Gravettian sites are similarly suggestive of variation and potential for interesting work.

To date, the similarities of Russian MUP archaeology to Western/Central European archaeology have been most obvious in Western discussion of the topic, particularly in studies arguing for widespread, open social networks during this time period. The variability of the Russian record, and the presence of industries that do not currently fit into the Aurignacian-Gravettian classification, has perhaps not yet been fully acknowledged in Western understanding of the European Upper Palaeolithic. Now that the range of cultural diversity within the European MUP is becoming clearer, the time is ripe for a reappraisal of the Russian evidence.

There are, however, certain peculiarities of the Russian record that must be acknowledged before any sort of synthetic approach can be countenanced, some of which have already been mentioned above. The nature of the Russian landscape, with its dearth of caves and rock shelters, has certainly led to differences in the archaeological record, including the original function of sites, taphonomy, and site visibility (Hoffecker 2011). The isolation of the Kostenki-Borshchevo area is another factor to be considered. Although Russian MUP sites are also known outside of this region, they are primarily sites of the Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture; earlier Gravettian industries are apparently restricted to Kostenki-Borshchevo. The distance to the nearest Gravettian sites in Ukraine and, beyond that, Romania and Moravia, poses huge problems for contextualising these assemblages. It is around 600 miles from Kostenki to the nearest major early Gravettian site, at Molodova-5, Ukraine.

Concerning the best approach to the study of Russian lithic assemblages, a few points are worth noting. In order to obtain the necessary typological and technological information for comparison of assemblages, first-hand examination of the collections is essential. Tomášková (2003) has demonstrated (in a comparison of lithic assemblages from Willendorf and Dolní Věstonice) that uncritical comparisons of published outline data of lithic collections can be misleading, particularly when that data was produced in contexts of dissimilar intellectual traditions. As with any other assemblage, full consideration of the excavation and curatorial protocols employed is vital. For the Western archaeologist, this includes an understanding of the differences between Soviet and Western archaeological practice. Finally, for comparisons to be most productive, it makes sense to take account of the large amount of work that has already been done on, for example, bladelet production by colleagues elsewhere in Europe, and to study and record the same features in Russian assemblages.

Conclusions

There is wide interest amongst western European and Anglophone archaeologists in the archaeology of Russia but, to date, work has been piecemeal. Ambitious research, such as that of Soffer (1985), which focused on the archaeology of Ukraine, has shown us a way forward, but has not been followed up by similar work that would flesh out cross-continental comparisons. Many Russian assemblages, even the particularly important ones, have remained under-studied or even entirely unstudied for decades (including by Russian colleagues), representing a huge untapped resource. The potential rewards of intensive study of Russian Upper Palaeolithic assemblages are difficult to estimate but certainly more than justify the difficulties involved.

There are obvious locally-focused questions to be asked of the assemblages, including: which industries and faciés thereof made up the Russian MUP? What exactly does the Gorodtsovian represent – an intrusive/local cultural phenomenon, or a reflection of site function, taphonomy, etc.? How did the Gravettian change over time? Is there any sign of continuity between the local Gravettian and the Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture, or is the latter more likely to be an intrusive industry? Can the differing geographical distributions of the Kostenki-Avdeevo Culture and other industries be explained? These questions, of course, are debated by Russian colleagues, with varying degrees of consensus on their solutions; they have ramifications for international understanding of Upper Palaeolithic cultural processes.

Broader questions that these data might be used to address include the following. How similar are MUP lithic assemblages across Europe? Did the level of similarity change over time? The MUP saw significant climatic and environmental upheavals – is there any apparent correlation between these changes and changes in the archaeological record? How can the lithic data contextualise our understanding of other aspects of the archaeology, e.g. portable art (for example, the late MUP female figurines, often called ‘Venus’ figurines)? There is an ongoing Western European/Anglophone debate on the purpose of Gravette points and other backed artefacts, especially concerning projectile and bow technology; has Russian evidence and work by Russian colleagues been properly considered in that debate?

It is past time for the full spectrum of the Russian archaeological record to receive the comprehensive international publication and attention it deserves. Presently, the Western understanding of the European Upper Palaeolithic is impoverished by our lack of knowledge of this archaeology and the work of Russian colleagues. The scope for work of benefit to all parties is enormous and, although it presents challenges, it is to be hoped that we can rise to them.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks are due to my DPhil supervisors, Nick Barton and Tom Higham, and my MSc supervisor, Andy Garrard, for all their help and support. Many thanks also to Rob Dinnis for being a sounding board and his advice and support over many years, and to Katerina Douka for discussions on radiocarbon dating. Thanks to Nick Barton and Rob Dinnis for their comments on a draft of this paper, and an anonymous reviewer for some helpful recommendations. I am very grateful to Sergey Lev and Konstantin Gavrilov for allowing me to participate in their excavations at Zaraysk and Khotylevo-2 in the summer of 2012 and for some illuminating discussions. Daria Escova has also been extremely helpful in sharing some of her knowledge of the Russian Palaeolithic with me. The MSc and DPhil work on which this paper is based has been funded by the AHRC. Travel grants were provided by Wolfson College, Oxford and the Meyerstein Fund, School of Archaeology, University of Oxford.

Bibliography

Amirkhanov, K.A. (ed.) (2009) Issledovaniya paleolita v Zaraiske 1999–2005. Moscow: Paleograf.

Anikovich, M. V. (2005a) The Early Upper Paleolithic in Eastern Europe. In: A. P. Derevianko (ed.) The Middle to Upper Paleolithic Transition in Eurasia: Hypotheses and facts, pp. 79–93. Novosibirsk: Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography Press.

Anikovich, M. V. (2005b) O khronologii paleolita kostyonkovsko-borshchevskogo rajona. Arkheologiya, etnografiya i antropologiya Evrazii 3(23), 70–86.

Anisyutkin, N. K. (2006) Severnyj punkt Kostyonok 4 i kul’turno-khronologicheskaya interpretatsiya pamyatnika. In: M. V. Anikovich (ed.) Kostyonki i rannyaya pora verkhnego paleolita Evrazii: obshchee i lokal’noe (Materialy mezhdunarodnoj konferentsii k 125–letiyu otkrytiya paleolita v Kostyonkakh, 23–26 avgusta 2004 g.), pp. 101–13. Saint-Petersburg: Nestor-Istoriya.

Aranguren, B., Becattini, R., Mariotti Lippi, M. and Revedin, A. (2007) Grinding Flour in Upper Palaeolithic Europe (25 000 Years BP). Antiquity 81(314), 845–55.

Bessudnov, A. A. (2009) Istoriya izucheniya paleolita bassejna Verkhnego i Srednego Dona. Nauchnye vedomosti BelGU (Seriya ‘Istoriya. Politologiya. Ekonomika. Informatika’) 9(11), 86–96.

Borgia, V. (2009) Ancient Gravettian in the South of Italy: Functional analysis of backed points from Grotta Paglicci (Foggia) and Grotta della Cala (Salerno). Palethnologie 1, 45–65.

Borgia, V., Ranaldo, F., Ronchitelli, A. and Wierer, U. (2011) What Differences in Production and Use of Aurignacian and Early Gravettian Lithic Assemblages? The case of Grotta Paglicci (Rignano Garganico, Foggia, Southern Italy). In: N. Goutas, L. Klaric, D. Pesesse and P. Guillermin (eds) À la recherche des identités gravettiennes : actualités, questionnements et perspectives : actes de la table ronde sur le Gravettien en France et dans les pays limitrophes, Aix-en-Provence, 6–8 octobre 2008, pp. 161–74. Paris: Société Préhistorique Française.

Bronk Ramsey, C., Higham, T. F. G., Owen, D. C., Pike, A. W. G. and Hedges, R. E. M. (2002) Radiocarbon Dates from the Oxford AMS System: Datelist 31. Archaeometry 44(3, Suppl. 1), 1–149.

Bulkin, V. A., Klejn, L. and Lebedev, G. S. (1982) Attainments and Problems of Soviet Archaeology. World Archaeology, 13(3), 272–95.

Chabai, V. (2003) The Chronological and Industrial Variability of the Middle to Upper Paleolithic Transition in Eastern Europe. In J. Zilhão and F. d’Errico (eds) The Chronology of the Aurignacian and of the Transitional Technocomplexes. Dating, Stratigraphies, Cultural Implications, Trabalhos de Arqueologia 33, pp. 71–86. Lisbon: Instituto Português de Arqueologia.

Conard, N. J., and Moreau, L. (2004) Current Research on the Gravettian of the Swabian Jura. Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte 13, 29–59.

Davis, R. S. (1983) Theoretical Issues in Contemporary Soviet Paleolithic Archaeology. Annual Review of Anthropology 12, 403–28.

Djindjian, F., Kozlowski, J. and Otte, M. (1999) Le Paléolithique supérieur en Europe. Paris: Armand Colin.

Douka, K., Higham, T. and Sinitsyn, A. (2010) The Influence of Pretreatment Chemistry on the Radiocarbon Dating of Campanian Ignimbrite-aged Charcoal from Kostenki 14 (Russia). Quaternary Research 73(3), 583–87.

Efimenko, P. P. (1953) Pervobytnoe obshchestvo. Kiev: Izdatelstvo AN USSR.

Efimenko, P. P. (1956) K voprosu o kharaktere istoricheskogo protsessa v pozdnem paleolite Vostochnoj Evropy. (O pamyatnikakh tak nazyvaemogo seletskogo i grimal’dijskogo tipa). Sovetskaya Arkheologiya XXVI, 28–53.

Efimenko, P. P. (1960) Peredneaziatskie elementy v pamyatnikakh pozdnego paleolita Severnogo Pricher-nomor’ya. Sovetskaya Arkheologiya 4, 14–25.

Fedele, F., Giaccio, B. and Hajdas, I. (2008) Timescales and Cultural Process at 40,000 BP in the Light of the Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption, Western Eurasia. Journal of Human Evolution 55(5), 834–857.

Gavrilov, K. N. (2008) Verkhnepaleoliticheskaya stoyanka Khotylyovo 2. Moscow: Taus.

Germonpré, M., Lázničková-Galetová, M. and Sablin, M. (2012) Palaeolithic Dog Skulls at the Gravettian Předmostí Site, the Czech Republic. Journal of Archaeological Science 39(1), 184–202.

Giaccio, B., Isaia, R., Fedele, F., Di Canzio, E., Hoffecker, J., Ronchitelli, A., Sinitsyn, A., Anikovich, M., Lisitsyn, S. and Popov, V. (2008) The Campanian Ignimbrite and Codola Tephra Layers: Two temporal/stratigraphic markers for the Early Upper Palaeolithic in southern Italy and eastern Europe. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 177(1), 208–26.

Graf, K. E. (2009) ‘The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly’: Evaluating the radiocarbon chronology of the middle and late Upper Paleolithic in the Enisei River valley, south-central Siberia. Journal of Archaeological Science 36(3), 694–707.

Grigor’ev, G. (1993) The Kostenki-Avdeevo Archaeological Culture and the Willendorf-Pavlov-Kostenki-Avdeevo Cultural Unity. In: O. Soffer and N. Praslov (eds) From Kostenki to Clovis: Upper Paleolithic-Paleo-Indian Adaptations, pp. 51–66. New York: Plenum Press.

Haesaerts, P., Damblon, F., Bachner, M. and Trnka, G. (1996) Revised Stratigraphy and Chronology of the Willendorf II Sequence, Lower Austria. Archaeologia Austriaca 80, 25–42.

Haesaerts, P., Borziac, I., Chekha, V. P., Chirica, V., Drozdov, N. I., Koulakovska, L., Orlova, L. A., van der Plicht, J. and Damblon, F. (2010) Charcoal and Wood Remains for Radiocarbon Dating Upper Pleistocene Loess Sequences in Eastern Europe and Central Siberia. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 291(1–2), 106–27.

Higham, T. F. G. (2011) European Middle and Upper Palaeolithic Radiocarbon Dates are Often Older than they Look: Problems with previous dates and some remedies. Antiquity 85, 235–49.

Higham, T. F. G., Jacobi, R. M., Basell, L., Bronk Ramsey, C., Chiotti, L. and Nespoulet, R. (2011) Precision Dating of the Palaeolithic: A new radiocarbon chronology for the Abri Pataud (France), a key Aurignacian sequence. Journal of Human Evolution 61(5), 549–63.

Hoffecker, J. (2011) The Early Upper Paleolithic of Eastern Europe Reconsidered. Evolutionary Anthropology 20(1), 24–39.

Hoffecker, J., Holliday, V., Anikovich, M., Sinitsyn, A., Popov, V., Lisitsyn, S., Levkovskaya, G., Pospelova, G., Forman, S. and Giaccio, B. (2008) From the Bay of Naples to the River Don: The Campanian Ignimbrite eruption and the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition in Eastern Europe. Journal of Human Evolution 55(5), 858–70.

Holliday, V., Hoffecker, J., Goldberg, P., Macphail, R., Forman, S., Anikovich, M., and Sinitsyn, A. (2007) Geoarchaeology of the Kostenki-Borshchevo Sites, Don River Valley, Russia. Geoarchaeology 22(2), 181–228.

Jacobi, R. M. and Higham, T. F. G. (2008) The ‘Red Lady’ Ages Gracefully: New ultrafiltration AMS determinations from Paviland. Journal of Human Evolution 55, 898–907.

Klaric, L. (2007) Regional Groups in the European Middle Gravettian: A reconsideration of the Rayssian technology. Antiquity 81, 176–90.

Klein, R. G. (1969) Man and Culture in the Late Pleistocene: A case study. San Francisco: Chandler Publishing Company.

Kozłowski, J. K. (1986) The Gravettian in Central and Eastern Europe. Advances in World Archaeology 5, 131–200.

Kozłowski, J. K. (2008) End of the Aurignacian and the Beginning of the Gravettian in the Balkans. In: A. Darlas and D. Mihailović (eds) The Palaeolithic of the Balkans, British Archaeological Reports International Series 1819, pp. 3–14. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Lisitsyn, S. N. (1998) Mikroplastinchatyj inventar’ verkhnego sloya Kostyonok 1 i nekotorye problemy razvitiya mikroorudij v verkhnem paleolite Russkoj ravniny. In: K. A. Amirkhanov (ed.) Vostochnyj Gravett, pp. 299–308. Moscow: Nauchnyj Mir.

Marom, A., McCullagh, J. S. O., Higham, T. F. G., Sinitsyn, A. A. and Hedges, R. E. M. (2012) Single Amino Acid Radiocarbon Dating of Upper Paleolithic Modern Humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109(18), 6878–881.

Moreau, L. (2010) Geißenklösterle. The Swabian Gravettian in its European context. Quartär 57, 79–93.

Moreau, L. (2011) La fin de l’Aurignacien et le début du Gravettien en Europe centrale: continuité ou rupture? Étude comparative des ensembles lithiques de Breitenbach (Sachsen-Anhalt, D) et Geißenklösterle (AH I) (Bade-Wurtemberg D). Notae Praehistoricae 31, 21–29.

Otte, M. and Noiret, P. (2003) L’Europe gravettienne. In: R. Desbrosse and A. Thévenin (eds) Préhistoire de l’Europe. Des origines à l’Âge du Bronze: Actes du 125e Congrés national des Sociétés historiques et scientifiques (Lille, 2000), pp. 227–39. Paris: CTHS.

de la Peña Alonso, P. (2012) A propósito del Gravetiense… El paso de cultura a tecnocomplejo: un caso ejemplar de pervivencia particularista. Complutum 23(1), 41–62.

Pesesse, D. (2006) La ‘pointes à dos alternes’, un nouveau fossile directeur du Gravettien? Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 103(3), 465–78.

Pesesse, D. (2008) Le statut de la fléchette au sein des premiéres industries gravettiennes. Paléo 20, 45–58.

Pesesse, D. (2010) Quelques repères pour mieux comprendre l’émergence du Gravettien en France. Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 107(3), 465–87.

Pettitt, P. B., Davies, S. W. G., Gamble, C. S. and Richards, M. B. (2003) Palaeolithic Radiocarbon Chronology: Quantifying our confidence beyond two half-lives. Journal of Archaeological Science 30, 1685–693.

Prat, S., Péan, S., Crépin, L., Drucker, D., Puaud, S., Valladas, H., Lázničková Galetová, M., van der Plicht, J. and Yanevich, A. (2011) The Oldest Anatomically Modern Humans from Far Southeast Europe: Direct dating, culture and behavior. PLoS ONE 6(6), e20834.

Pyle, D., Ricketts, G., Margari, V., van Andel, T., Sinitsyn, A., Praslov, N. and Lisitsyn, S. (2006) Wide Dispersal and Deposition of Distal Tephra During the Pleistocene ‘Campanian Ignimbrite/Y5’ Eruption, Italy. Quaternary Science Reviews 25(21–22), 2713–2728.

Revedin, A., Aranguren, B., Beccatini, R., Longo, L., Marconi, E., Mariotti Lippi, M., Skakun, N., Sinitsyn, A., Spiridinova, E. and Svoboda, J. (2010) Thirty Thousand-year-old Evidence of Plant Food Processing. PNAS 107(44), 18815–18819.

Roebroeks, W., Mussi, M., Svoboda, J. and Fennema, K. (eds) (2000) Hunters of the Golden Age. Leiden: University of Leiden Press.

Rogachev, A. N. (1955) Kostenki IV – Poselenie drev-nekamennogo veka na Donu. Materialy i issledovaniya po arkheologii SSSR 45, 9–161.

Rogachev, A. N. (1957) Mnogoslojnye stoyanki kostenkovsko-borshevskogo raiona na Donu i problema razvitiya kul’tury v epokhu verkhego paleolita na Russkoi ravnine. Materialy i issledovaniya po arkheologii SSSR 59, 9–134.

Rogachev, A. N. and Anikovich, M. V. (1982) Kostyonki 4 (Aleksandrovskaya stoyanka). In: N. D. Praslov and A. N. Rogachev (eds) Paleolit kostyonkovsko-borshchevskogo rajona na Donu 1879–1979: Nekotorye itogipolevykh issledovanij, pp. 76–85. Leningrad: Nauka.

Rogachev, A. N., Anikovich, M. V. and Dmitrieva, T. N. (1982) Kostyonki 8 (Tel’manskaya stoyanka). In: N. D. Praslov and A. N. Rogachev (eds) Paleolit kostyonkovsko-borshchevskogo rajona na Donu 1879–1979: Nekotorye itogi polevykh issledovanij, pp. 92–109. Leningrad: Nauka.

Rogachev, A. N. and Sinitsyn, A. A. (1982) Kostyonki 15 (Gorodtsovskaya stoyanka). In: N. D. Praslov and A. N. Rogachev (eds) Paleolit kostyonkovsko-borshchevskogo rajona na Donu 1879–1979: Nekotorye itogi polevykh issledovanij, pp. 162–71. Leningrad: Nauka.

Rogachev, A. N. and Anikovich, M. V. (1984) Pozdnii paleolit Russkoi ravniny i Kryma. In P. I. Boriskovskii (ed) Paleolit SSSR, pp. 162–271. Moscow, Nauka.

Sedov, S. N., Khokhlova, O. S., Sinitsyn, A. A., Korkka, M. A., Rusakov, A. V., Ortega, B., Solleiro, E., Rozanova, M. S., Kuznetsova, A. M. and Kazdym, A. A. (2010) Late Pleistocene Paleosol Sequences as an Instrument for the Local Paleographic Reconstruction of the Kostenki 14 Key Section (Voronezh oblast) as an Example. Eurasian Soil Science 43(8), 876–892.

Simakova, A. N. (2006) The Vegetation of the Russian Plain During the Second Part of the Late Pleistocene (33–18ka). Quaternary International 149(1), 110–114.

Sinitsyn, A. A. (1999) Chronological Problems of the Palaeolithic of Kostienki-Borschevo Area: Geological, palynological and 14C perspectives. In: J. Evin, C. Oberlin, J.-P. Daugas and J.-F. Salles (eds) 14C et archéologie. Actes du 3ème Congrès International (Lyon, 6–10 avril 1998), pp. 143–50. Lyon: Société Préhistorique Française.

Sinitsyn, A. A. (2003) A Palaeolithic ‘Pompeii’ at Kostenki, Russia. Antiquity 77, 9–14.

Sinitsyn, A. A. (2007) Variabilité du Gravettien de Kostienki (Bassin moyen du Don) et des territoires associés. Paléo 19, 181–202.

Sinitsyn, A. A. (2010) The Early Upper Palaeolithic of Kostenki: Chronology, taxonomy, and cultural affiliation. In: C. Neugebauer-Maresch and L. R. Owen (eds) New Aspects of the Central and Eastern European Upper Palaeolithic – methods, chronology, technology and subsistence (Symposium by the Prehistoric Commission of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, November 9–11, 2005), pp. 27–48. Vienna: Osterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Soffer, O. (1985) The Upper Paleolithic of the Central Russian Plain. London: Academic Press.

Soffer, O. (2004) Recovering Perishable Technologies through Use Wear on Tools: Preliminary evidence for Upper Paleolithic weaving and net making. Current Anthropology 45(3), 407–13.

Stepanchuk, V. N.; Cohen, V. Y. and Pisarev, I. B. (1998) Mira, a New Late Pleistocene site in the Middle Dnieper, Ukraine (preliminary report). Pyrenae 29, 195–204.

Svoboda, J. A. (2007) The Gravettian on the Middle Danube. Paléo 19, 203–20.

Tarasov, L. M. (1979) Gagarinskaya stoyanka i eyo mesto v paleolite Evropy. Leningrad: Nauka.

Tomášková, S. (2003) Nationalism, Local Histories and the Making of Data in Archaeology. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Society 9(3), 485–507.

Vandiver, P. B., Soffer, O., Klima, B. and Svoboda, J. (1989) The Origins of Ceramic Technology at Dolni Věstonice, Czechoslovakia. Science 246, 1000–1008.

Vasil’ev, S. A. (2008) Drevnejshee proshloe chelovechestva: Poisk rossiiskikh uchyonykh. Saint Petersburg: RAN IIMK.

Vishnyatsky, L. B. and Nehoroshev, P. E. (2004) The Beginning of the Upper Paleolithic on the Russian Plain. In: P. J. Brantingham, S. L. Kuhn and K. W. Kerry (eds) The Early Upper Paleolithic Beyond Western Europe, pp. 80–96. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wierer, U. (2013) Variability and Standardization: The early Gravettian lithic complex of Grotta Paglicci, Southern Italy. Quaternary International 288, 215–238.

Zheltova, M. N. (2009) Kostenki-4: The position of artifacts in space and time (The analysis of the cultural layer). Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia 37(2), 19–27.

Zheltova, M. N. (2011) Ostriya aleksandrovskogo tipa: kontekst, morfologiya, funktsiya. In: K. N. Gavrilov (ed.) Paleolit i Mezolit Vostochnoj Evropy, pp. 226–34. Moscow: Institut arkheologii RAN/Taus.