7. Le Cuzoul De Gramat (Lot, France): A key sequence for the early Holocene in southwest France

Abstract

Explored for the first time by Lacam between 1920–1930, the Cuzoul de Gramat is one of the most famous French Mesolithic sites. Since 2005, a series of new excavations have been undertaken. The aim of this paper is to propose an assessment of our recent work, which outlines previous data and confirms the significant residual archaeological potential of the site, which is about to quickly become an important regional sequence for the first half of the Holocene.

Introduction

The Causses of Haut-Quercy, located between the Pyrenean and the Massif Central mountain ranges, offer one of the most important concentrations of Mesolithic sites known within southern France (Valdeyron et al. 2009). Among those sites, Cuzoul de Gramat, explored for the first time in the 1920s and 1930s by Lacam, is particularly famous (Lacam et al. 1944). The site is located in the centre of the karstic plateau of Gramat (Causse de Gramat) in the northern part of the Lot region (Figure 7.1). This low altitude Causse (average 300 m above sea level) displays a remarkable number of dolinas, swallow holes, and subterranean rivers.

This system of valleys, plateaus, and slopes offers a variety of habitats in the present day with abundant animal, mineral, and vegetal resources. This seems to have been the case at least since Mesolithic times, with red deer, boar, and roe deer being the most hunted animals at a regional scale during this period (Valdeyron et al. 2011). In terms of mineral resources, flint is locally abundant and generally of very good quality. It is found in secondary or tertiary formations in primary deposits or in the alluvial deposits of the rivers Dordogne, Lot, and Célé. The raw material analysis indicates that the occupants of Cuzoul obviously took advantage of these local resources (at distances less than 20 km) (Constans 2013).

The regional vegetation history can be reconstructed today thanks to recent charcoal data from five prehistoric sites located on the Causse de Gramat, including the first charcoal samples collected in secure stratigraphic contexts from Cuzoul (levels in place dated by radiocarbon; see below). These indicate three major phases of landscape evolution (Henry et al. 2013). While the late Glacial is marked by the early decline of softwoods (mainly juniper and scots pine) and their almost complete disappearance, the early Holocene sees the development of oak and its associated taxa in a highly contrasted landscape. Hence, the vegetation surrounding the Mesolithic sites of the Causse de Gramat is already characterised by the absolute dominance of a variety of broad-leaved trees and shrubs. During the early and middle phases of the Mesolithic, deciduous oak woodlands develop progressively, at the cost of shrubby clearances and fruticeae of Rosaceae prunoideae and maloideae. The late Mesolithic seems to be marked by an increase in humidity and the installation of more mature formations in the form of oak woodlands with a higher biodiversity. However, the improvement of the climatic conditions during the course of the Atlantic period did not lead to a significant increase of Mediterranean taxa, as can be observed nowadays on the Causse. The vegetation seems to remain strictly supra-Mediterranean at least until the Bronze Age (ibid.).

The aim of carrying out new excavations is not only to validate, but also to complete the observations made by our predecessors. Since archaeological knowledge has increased and a whole number of analytical tools and methods have been developed over the last decades, we hope to acquire in the following years an interdisciplinary vision of the nature and function of the successive occupations of Cuzoul de Gramat. In this paper, we will discuss both the old excavations, as well as present the first results from recent fieldwork.

Figure 7.1. Geographic location of the site of Le Cuzoul de Gramat (drawing by N. Valdeyron, map from F. Tessier and K. Gernigon).

Presentation of the site and history of the archaeological investigations

The site is located at the bottom of a large dolina, one of the ‘cloups’ that are so typical of the landscapes of Quercy. However, this configuration is quite rare, since the size of the dolina easily exceeds what prevails in other neighbouring sites, such as Escabasses, or even Roucadour. The flat bottom of this oval-shaped depression stretching towards the north-northwest is more than 200 m long and 100 m wide. These unusual dimensions give the site an almost monumental appearance. The feeling of confinement, so common in these depressions, which are often surrounded by trees, is entirely absent here. This impression, in addition to the effect induced by the dolina’s considerable size, is also due to the relatively shallow slope of its sides, which are only rarely vertical and are often in the form of small terraces. These structures testify to the former agricultural function of this vast natural humidity reservoir, which now is only used for sheep and cattle, but which was formerly utilised for cereal cultivation.

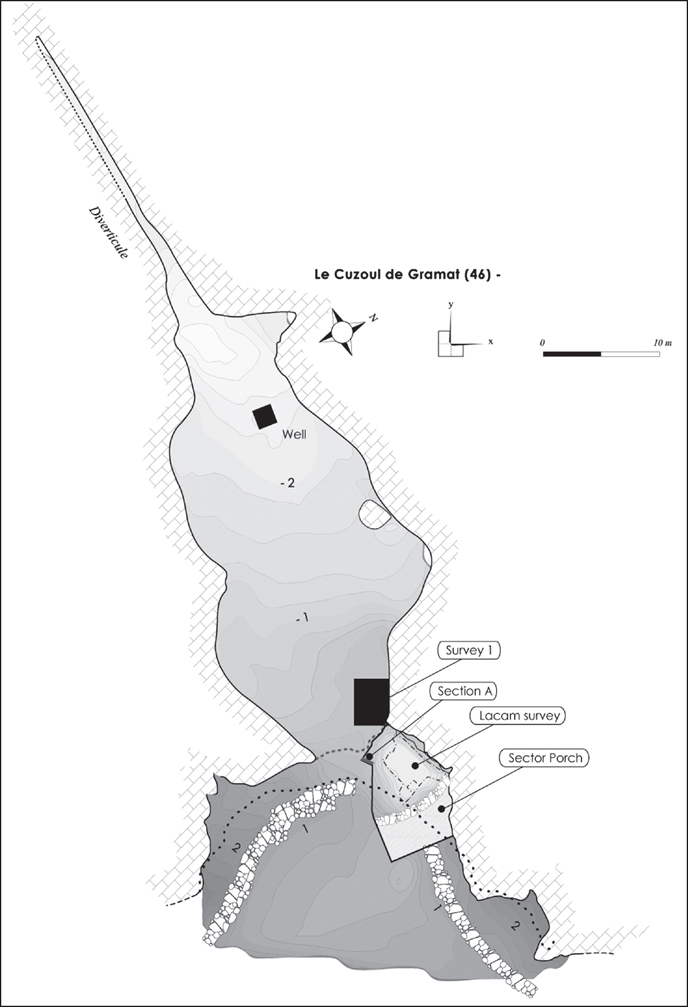

The site itself, formed by the cavity and the surrounding area, opens in a bank of Jurassic limestone, forming a rocky escarpment up to 10 metres high and facing east (Figure 7.2). On both sides of the entrance to the cavity, the limestone stretches for several tens of meters, forming a continuous line of shelters of varying depth (Figure 7.3). A wall forms a raised passage (2 to 3 metres wide depending on location) between the limestone wall and the bottom of the dolina, bounding its western side. This corridor, which extends beyond the rock fall, is an old access road from the top of the plateau. The north side contains a similar feature; however, once past the area of the porch itself, the rapid reduction of the height of the wall quickly limits the protective nature of the rock fall.

Figure 7.2. View of the entrance of the cave from the bottom side of the dolina (photo by N. Valdeyron).

Figure 7.3. Map of the deposit with various sectors explored (drawing by N. Valdeyron).

Currently, the entrance to the cave, which is almost 6 meters wide and relatively low (2 metres in height up to the level of the spire), leads directly to a first relatively large chamber (40 × 15 × 3 m), at the bottom of which a man-made well protects a perennial captive sheet. Beyond the well begins a narrow, but passable corridor leading, after a few hundred feet, to a second, significantly smaller chamber (8 × 3 × 2 m). Only the first chamber, two thirds of which is regularly flooded in winter by the rise of the water level, has yielded evidence for prehistoric occupation.

If we refer to the official version (Lacam et al. 1944), the only work on the site was performed by Lacam and Niederlender, who operated continuously from 1923 to 1933. First, three trenches were dug inside the cave. Their exact location is unknown, but they were probably located deep inside the first chamber, as comments by Lacam suggest that the stratigraphic levels found were heavily disrupted by the presence of the water table. This fact led the excavators to start working outside the cave, in the North shelter, from 1927 onwards. Here, a stratigraphic sequence of more than four meters was uncovered, which revealed, in particular, several Mesolithic levels. These levels, containing trapezes, were attributed to the ‘Tardenoisian’.

At the base of these ‘Tardenoisian’ levels, the discovery of the burial of a young adult ensured the celebrity of the site; the official excavation was extended until 1933, when the cutting under the porch was closed and back-filled. Lacam’s excavation logbooks tell us that he actually returned to the site long after its closure. For example, in 1947 he opened a cutting of a few square metres, located about ten metres in front of the rock-shelter. This allowed him to locate the stratigraphic sequence he had already observed under the porch. This information is important, because it suggests that the site extends into the dolina – and is well preserved – beyond the area of the rock-shelter, which could indicate the presence of open-air occupation at the site.

New works: evaluating previous findings, obtaining new data

As a first step and in keeping with what was originally asked of us, our excavations were restricted to the porch where Lacam’s excavation had taken place. The back-fill from Lacam’s trench was re-excavated and fully sieved. This titanic operation involved the processing of almost 70 m3 of sediment and occupied us for the first three excavation seasons.

After this, one of the edges of Lacam’s trench was selected to act as a reference section (called ‘Section A’), which to date has attained the upper Sauveterrian levels. Inside the cavity, in the continuity of Lacam’s survey, a sondage (referred to as ‘Survey 1’), small at first and progressively enlarged, was opened during the second campaign in order to access in situ levels as quickly as possible. In 2008, the excavation reached the top of the Mesolithic sequence. Finally, a fourth excavation area (called ‘Sector Porch’) was opened. This corresponds to the control area, unexcavated by Lacam, and separated from his trench by a stone wall built at the time of the site’s closure (Figure 7.3). We present below the preliminary results obtained so far for the first three excavation zones, since in situ levels have not yet been recovered from the Sector Porch.

The ‘Survey Lacam’

In this area, there was no new excavation since only the sediment of the former excavation was removed and sieved, i.e. an infilling resulting from the mixing of all levels excavated by Lacam, from the Epipalaeoltihic to the Neolithic. Consequently, neither stratigraphic nor specific data relating to the sedimentary context have been obtained. However, the residual information yielded by this survey is important and confirms, and sometimes even adds, to what we already knew. Several thousand additional artefacts, mainly lithic, have been recovered. Among these are hundreds of stone and abundant animal bone tools, many faunal remains, as well as Neolithic or more recent pottery fragments, the latter being less well represented. An obvious but important point to make here is how the lack of sieving in the earlier excavations greatly limited the representativeness of Lacam’s collection. This is true regardless of the quality of Lacam’s work, which should also be recognised. Luckily, the abundant material that was collected helped to clarify the different occupation phases of the site, either by providing more precise cultural data or by substantially completing the general picture suggested by Lacam.

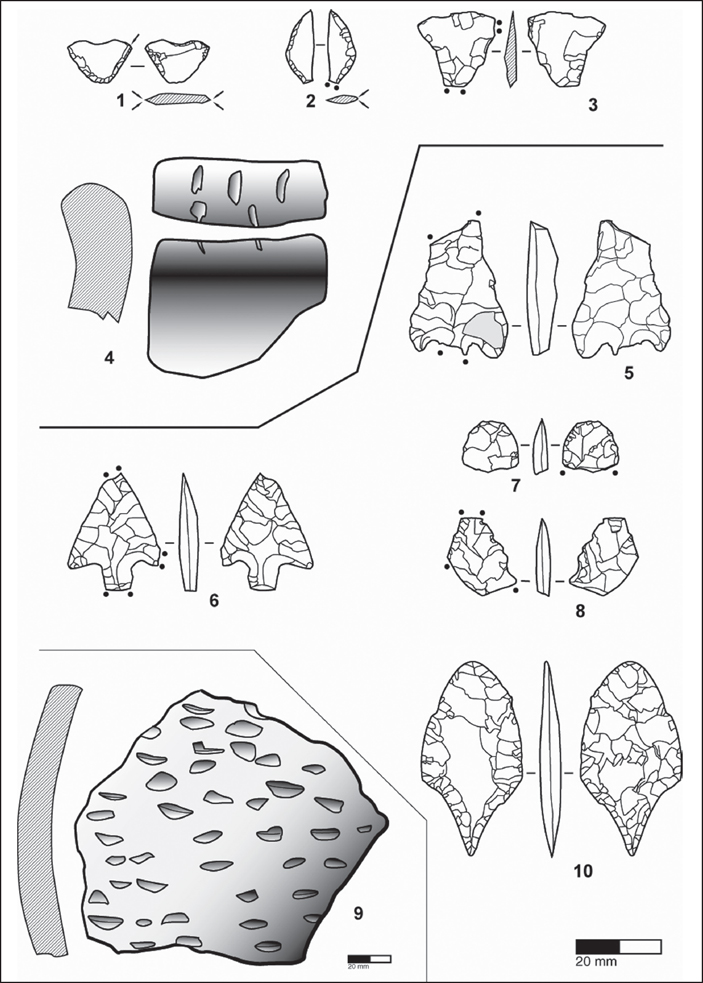

The earliest occupation reaches back to the Azilian period, perhaps to a classic phase of this culture, even though its chronology is still poorly understood in the Quercy region (Valdeyron & Detrain 2009). Probably on the basis of the observation of mixed assemblages, Lacam identified what he called an Azilo-Sauveterrian layer I (titles have varied, since the terms ‘Sauveterrian’ and ‘evolved Post-Azilian’ were also used, but the corresponding assemblages were clearly mixed). Material collected in the backfill from Lacam’s excavations clearly calls for the attribution of this first occupational phase to the Azilian only (Figure 7.4), e.g. a series of curved backed points (No. 1–10), no true Malaurie points, and a few tools made on blades, including one truncated blade with bilateral retouch (No. 11). These finds are representative of the local Azilian tradition as it is found, for example, in the layers of Murat shelter, or in Level 4 of Pégourié (ibid.). The distal part of a unilateral antler harpoon (No. 17) completes this assemblage. Three drilled deer canines may be connected to this assemblage, though they could also be more recent (No. 12–14). Two bone fragments carry fine engravings, organized in parallel lines on one (No. 15), while the other exhibits a more complex organisation (No. 16). These decorations appear to be non-figurative.

In the vision of the site developed by Lacam, the Azilian pieces appear mixed with industries that can today be attributed to an early or middle Mesolithic phase. These industries are largely underrepresented in the earlier work because of the absence of sieving. Even though the interpretation resulting from the examination of the material collected from the backfill of Lacam’s trench and found while restoring ‘Section A’ (see below) must remain cautious, it seems clear that a Sauveterrian occupation succeeded the initial Azilian occupation. This interpretation is based on the characteristic nature of some microlithic armatures, particularly geometric triangles. Even though isosceles forms are rare, a relatively important amount of Montclus triangles, or other pieces related to this type, have been identified, which clearly indicate the occupation of the site at the end of the Early and/or during the Middle Sauveterrian.

Figure 7.4. Survey Lacam: lithic and bone material assigned to the Azilian (drawings by N. Valdeyron and B. Marquebielle).

The majority of the typical material, i.e. the artefacts likely to provide a chrono-cultural diagnosis, alludes to occupation at the end of the Mesolithic period. This is true of the raw products obtained by indirect percussion, for notched or denticulate blades (Montbani type), many large armatures represented by a wide variety of trapezes (Figure 7.5, No. 2, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 11), triangular points (Figure 7.5, No. 1 and 3) or Montclus arrow type armatures (Figure 7.5, No. 4, 5, and 12). A preliminary use wear analysis of about a hundred notched blades showed a good state of preservation and demonstrated that they were voluntary tools used to scrape narrow pieces of wood, bone, or plant. Numerous bone and antler artefacts were also found in this context. Their cultural attribution is difficult, firstly because they mainly represent the waste of débitage items and secondly, because the exploitation of osseous materials during the Mesolithic is not yet well understood. Nevertheless, numerous objects fit into the technical transformation scheme of the recent/final Mesolithic, known from the study of Lacam’s collection (Marquebielle 2007), which showed that antler exploitation was organised following a débitage by sectioning.

Figure 7.5. Survey Lacam: lithic material assigned to the recent/final Mesolithic (drawing by N. Valdeyron).

The following occupation phase had previously gone completely unnoticed. It must be said that it is attested to only by a small number of objects, which were not known to be diagnostic or specific to the early Neolithic at the time of Lacam’s study. Surprisingly, but very positively, it seems several elements can be attributed to this period. These include a Betey segment, with its characteristic bow in double-bevel (Figure 7.6, No. 2). There is also a Châtelet arrow type (Figure 7.6, No. 1), with a typical isosceles triangle form and semi-abrupt bifacial retouch formed from two truncations (on this piece, only one of two truncations meets this definition). The length of the cutting edge, close to 15 mm, remains within the limits of the type. These two objects are certainly the most significant. Without great conviction however, another sharp armature could also be added to this small assemblage (Figure 7.6, No. 3). Finally, a pottery fragment, representing a decorated lip, could also support an attribution to the early Neolithic (Figure 7.6, No. 4).

No presence on the site during the Middle or the Late Neolithic can be detected in the material from Lacam’s excavations, nor on the basis of his 1944 publication, or the Museum collections. However, an intense occupation during the Chalcolithic/Bronze Age, having already been indicated by a date obtained from a pit discovered in 2005 inside the trench opened in the dolina (Ly 1237, 3510 ± 70 BP, c. 2026 to 1643 cal. BC), is clearly present. It is represented by a beautiful series of tanged arrowheads covered with bifacial retouch, associated with other types of armatures with the same type of retouch (Figure 7.6, No. 5, 6, 7, 8 and 10). An equally beautiful pottery shard belongs to the same chronological window, i.e. typical of the middle Bronze Age as it appears, for example, in level A1 of Roucadour (Nierderlender et al. 1966), or in a more reliable context from the same site, in level C1 of a recent excavation (Gasco 2000, 2004). The pinched, flat buttons decoration on this body fragment is indeed quite comparable to that described for Roucadour (Figure 7.6, No. 9). A fragment of cordon decorated with finger top impressions may also relate to the same horizon.

Figure 7.6. Survey Lacam: lithic and ceramic material assigned to the Early Neolithic and to the Bronze Age (drawing by N. Valdeyron).

The subsequent occupation phase is suggested by a small assemblage (barely seven pieces) of pottery fragments that had gone unnoticed. These bear no typical decor or shape. The major discriminant element is the paste, which is grey to black and fine, with an extraordinarily fine temper containing mica inclusions, typical of the extreme end of the Quercy Bronze productions (Gernigon et al. 2000).

After the end of the Bronze Age, the site was clearly occupied on several occasions. Again, the chrono-cultural diagnosis has been established on the basis of the ceramics. Some pieces evoke the Iron Age I. The antiquity is also represented by amphora fragments and common ceramics. There is also possibly material from the early Middle Ages and, more assuredly, the modern era.

Figure 7.7. Survey Lacam: stratigraphic profile ‘Section A’ (drawing by N. Valdeyron)

‘Section A’

Located on one of the sides of Lacam’s excavation trench, this reference section is still being worked on. Therefore, the data presented below are limited to its upper part. This careful excavation corresponded at first to a very limited excavation area (15 × 70 cm at the top), which now exceeds 1.5 m2 at the deepest levels. This has allowed us to gain an insight into the sedimentary dynamics in this area (Figure 7.7). They are marked for the most part by anthropogenic inputs (in the form of ash, charcoal, chips of snail shells, limestone rocks etc.). These are complemented in variable proportion (according to the levels), by more or less coarse natural inputs from the shelter’s wall, which may have fallen from the cliff, or have arrived in the shelter via the two lateral screes, which converge towards the cavity’s entrance.

Without going into a detailed characterisation of the sedimentary processes, the following elements can be noted:

1) The whole sequence (just over 1 m deep), is characterised by a very large amount of combustion features, showing a strong morphological and structural variability.

2) The sediment, poor in clay, is heavily loaded with ash and charcoal.

3) There are no sterile levels between the various archaeological deposits: whitish layers, identified by Lacam as ‘sterile’, are actually thick ash beds.

Three successive archaeological horizons have been identified in this area (from top to bottom). HA 1 is a pocket of disturbed sediment fallen (or voluntarily collapsed?) into the survey, likely at the time of its seal by Lacam. HA 2 is about 90 cm thick in the area where it is best preserved. This level seems to include mostly occupations belonging to the second Mesolithic (more recent assemblages may also be present). Barely started in 2008, HA 3 is also several tens of centimetres thick. It has delivered material relating to the Early and/or Middle Mesolithic (Figure 7.8, No. 31–38).

Several radiocarbon dates have been obtained for HA 2, giving the first series of indications as to the chronology of the site’s occupation during the second Mesolithic (see Table 7.1). The lithic assemblages associated with these dates consist, for the most part, of diagnostic elements, such as broad armatures (trapezes of the ‘Martinet’ type and ‘bastard’ points), deep-notched blades and bladelets, as well as microburins, all made on regular and quite broad elongated supports (Figure 7.8, No. 3–12). These associated artefacts characterise the upper part of the horizon (Ly-14204). In the lower part (Ly 14205 and 14459), the same types of artefacts are present (Figure 7.8, No. 13–16 and 24–26), but here they are associated with back edged pieces, made on narrower blades (Figure 7.8, No. 17–22, and 27–30), belonging to the Sauveterrian tradition.

Figure 7.8. Survey Lacam: lithic material, classified by stratigraphic unit, from ‘Section A’ (drawing by N. Valdeyron).

Of course, the coherency of these lithic assemblages has to be tested, since the conditions of their recovery do not allow them to be categorical for the moment. Our excavation area is still too small and located in a zone where several combustion pits may have disrupted the local stratigraphy. In any case, the data collected inside the cavity (see below) may be discordant, which also calls for caution.

‘Survey 1’

Opened in 2006, Survey 1 has been set up in the entrance area of the cavity, against the North wall, just a few metres from the limits of Lacam’s survey excavation. Initially of limited size (2 m2), it has gradually been expanded and now occupies an area slightly larger than 10 m2.

The upper part of the fill (US SG3100, 3200 and 4300) reflects the cave’s pastoral function during the modern era: the clay rich sediment results essentially from the taphonomic evolution of the excrements contained in the litter. Several features from this period (including the construction of a path and a pit-silo) disrupted the strata, destroying the first Mesolithic levels in places, and resulting in the prehistoric material being mixed with shards of glazed ceramic.

Below the levels attributed to modern times, a thin level limited to a few square metres delivered an archaeological soil (US SG 4550 and 4560) dating to the late Bronze age as indicated by the ceramic artefacts. A few typical potsherds are associated with coarser ceramic (such as the remains of a flat bottomed container), all arranged around a plain (SG 4200) structure marked by a thick base of rubefied clay.

Immediately below the Protohistoric (and also over dug in places by the base of the hearth) appears the first Mesolithic level (SG 5100). This consists of fine alternations of grey-brown sediment and ashes, and regular stratigraphic controls allowed for a very reliable planimetric exploration. This stratigraphic unit, which is a dozen centimetres thick, lies over a (perhaps) more compact grey, ashy level (SG 5200), which has been explored over a small area. Both have delivered relatively abundant archaeological material, consisting mostly of lithic pieces, bone remains, and whole or broken shells of the grove snail (Cepaea Nemoralis). Some osseous material was also discovered in these levels. In particular, a basal part of a red deer antler (US 5200) was exploited following the same débitage by sectioning method known from the study of Lacam’s collection. The chronological framework of bone and antler exploitation on the site can thus be clarified a little.

Hearth No. |

Radiocarbon (and calibrated) date |

Hearth F1 |

Ly 14204: 6200 ± 45 BP (5297 to 5038 cal. BC) |

Hearth F3 |

Ly 14205: 6490 ± 40 BP (5525 to 5368 cal. BC) |

Hearth F2b |

Ly 14459: 6760 ± 60 BP (5749 to 5558 cal. BC) |

Table 7.1. Radiocarbon dates that have been obtained for HA2.

At first sight, at least, the lithic material collected in these first two Mesolithic levels appears quite homogeneous and can, therefore, be attributed to the same occupation phase (Figure 7.9, No. 10–30). The common tools consist of notched blades and bladelets. The armatures are represented by asymmetrical trapezes (essentially of the Martinet type) and by long and, more rarely, short triangular points, among which are several so-called ‘bastard’ points. There are no narrow back edged pieces in this assemblage. Microburins made on large and broad supports are abundant. The date obtained for SG 5220 (Ly 14458: 6815 ± 40 BP, c. 5743–5638 cal. BC) places this set in a chronological position comparable to that of the hearths F3 and F2b from ‘Section A’, in which, as we mentioned before, broad armatures were associated with narrow back edged pieces. One of the hypotheses that can be proposed to explain this discrepancy in the range of armatures is that it is the result of taphonomic processes. Indeed, they seem to have been of consequence in relation to ‘Section A’, where the pits resulting from the construction and the use of the combustion features may have contributed to mixing the sediments and their associated (in this case, Sauveterrian) material. On the contrary, ‘Survey 1’ is clearly located in an area that has not been subjected to these types of post-depositional processes and the material can be considered as genuinely homogeneous.

Conclusions and perspectives

This brief presentation of the history of archaeological work on the site shows that the residual documentary potential of Cuzoul de Gramat, particularly given the extent of the old excavations, can be described as very important. The long sequence of Cuzoul, in the beautiful publication of 1944 by Lacam et al. (1944), has been confirmed and even added to by our preliminary results. Indeed, when the site was specifically targeted for studying the end of the Mesolithic, other periods that were not expected (e.g. the Early Neolithic or the Bronze age) could also be identified. Therefore, Cuzoul could become a reference site not only for the end of the Mesolithic period, but also for a number of other chronological phases hardly better documented on a local, regional, or sometimes even extra-regional scale. Without of course neglecting the interests of the Historic and Protohistoric occupations, since the corresponding levels have been explored with the same attention and the recovered vestiges have been entrusted to recognized specialists, it is now the Mesolithic sequence and the two periods surrounding it (i.e. the Azilian and the early Neolithic) which will hold our attention in the coming years.

Figure 7.9. Recent/final Mesolithic lithic material, classified by stratigraphic unit, from ‘Survey 1’ (drawing by N. Valdeyron).

Beyond the characterisation of the material productions, for which a defined number of studies are already available, such as that of the Lacam collection by Marquebielle (2007), our ambition is to provide an integrated approach to the site, representing the interdisciplinary nature of the researchers involved in this project. Even though the palynological testing inside the outer trench was inconclusive, charcoal and seed analyses have already begun and indicate the site’s potential for documenting palaeoenvironmental, as well as palaeoethnobotanical issues (Henry et al. 2011, 2013).

We hope to be able to present the first results of other approaches soon, such as raw material procurement, use-wear and zooarchaeological analyses, which will contribute to developing a wider reflection on the functional status of the occupations and the area that the site and its territory occupied in the Mesolithic landscape.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for his useful comments and Rowan Lacey for the final editing of the manuscript. It is thanks to her host institution, the CEPAM laboratory (CNRS UMR 7264, Nice, France) that A. Henry was able to carry out the charcoal study as a part of her PhD Thesis. The study of the charcoal material from Cuzoul de Gramat benefited from the financial support of the Regional Council of the Lot (France).

Bibliography

Constans, G. (2013) Approvisionnement et gestion des matières premières siliceuses de l’Epipaléolithique au Mésolithique: approches archéologiques et géologiques des assemblages lithiques du Cuzoul de Gramat (Lot). Mémoire de master 2, Université de Toulouse-Le Mirail.

Gasco, J. (2000) Pays de frontière ou coeur d’un territoire: que sait-on à ce jour du Bronze ancien quercinois? In: M. Leduc, N. Valdeyron and J. Vaquer (eds) Sociétés et espaces, Rencontres méridionales de préhistoire récente, pp. 187–99. Toulouse: Archives d’Ecologie Préhistorique.

Gasco, J. (2004) La stratigraphie de l’Âge du Bronze et de l’Âge du Fer à Roucadour (Thémines, Lot): analyse culturelle et incidences paléogéographiques. Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 101(3), 521–45.

Gernigon, K., Valdeyron, N. and Kerebel, J. (2000) Une occupation de la fin du premier âge du fer dans la doline des Escabasses (Thémines, Lot). Préhistoire du sud-ouest 7(1), 83–93.

Henry, A., Bouby, L. and Valdeyron, N. (2011) Environment and Plant Economy during the Mesolithic in the Haut Quercy (Lot, France): Anthropological and carpological data. Saguntum 11, 79–80.

Henry, A., Valdeyron, N., Bouby, L. and Thery-Parisot, I. (2013) History and Evolution of Mesolithic Landscapes in the Haut-Quercy (Lot, France): New charcoal data from archaeological contexts. The Holocene 23(1), 127–36.

Lacam, R., Niederlender, A. and Valois, H. (1944). Le gisement mésolithique du Cuzoul de Gramat, Archives de l’Insitut Paléontologie Humaine, mémoire 21. Paris: Masson.

Marquebielle, B. (2007) Première approche sur l’exploitation des matières dures animales au Mésolithique. L’industrie osseuse des niveaux du Mésolithique récent au Cuzoul de Gramat. Mémoire de Master II, Université Toulouse-Le Mirail.

Niederlender, A., Lacam, R. and Arnal, J. (1966) Le Gisement Néolithique de Roucadour (Thémines -Lot), IIIe supplément à Gallia Préhistoire. Paris: CNRS.

Valdeyron, N. and Detrain, L. (2009) La fin du Tardiglaciaire en Agenais, Périgord et Quercy : état de la question, perspectives. In: J. M. Fullola, N. Valdeyron and M. Langlais (eds) Les Pyrénées et leurs marges durant le Tardiglaciaire. Mutations et filiations techno-culturelles, évolutions paléo-environnementales, Actes du XIVème colloque international d’archéologie de Puigcerda, Hommages à Georges Laplace, pp. 493–517. Puigcerdà: Institut d’Estudis Ceretans.

Valdeyron, N., Bosc-Zanardo, B. and Briand, T. (2009) The Evolution of Stone Weapon Elements and Cultural Dynamics during the Mesolithic in Southwestern France: The case of the Haut Quercy (Lot, France). In: J.-M. Pétillon, M.-H. Dias-Meirinho, P. Cattelain, M. Honegger, C. Normand and N. Valdeyron (eds) Projectile Weapon Elements from the Upper Palaeolithic to the Neolithic, Proceedings of session C83, XVth World Congress UISPP, Lisbon, September 4–9, 2006, pp. 269–286. Paris: Palethnologie

Valdeyron, N., Briand, T., Bouby, L., Henry, A., Khedhaier, R., Marquebielle, B., Martin, H., Thibeau, A. and Bosc-Zanardo, B. (2011) The Mesolithic Site of Les Fieux (Miers, Lot): A hunting camp on the Gramat karst plateau? In: F. Bon, S. Costamagno and N. Valdeyron (eds) Hunting Camps in Prehistory. Current Archaeological Approaches. Proceedings of the International Symposium, May 13–15 2009, University Toulouse II-Le Mirail, pp. 331–41. Paris: Palethnologie.