9. Funerary Contexts: The case study of the Mesolithic shellmiddens of Muge (Portugal)

Introduction

The archaeological investigation of shellmiddens has had a long and rich development since those found along the Danish coast in the mid-1830s (Milner et al. 2007). However, it is only in the last few decades that the investigation of shellmiddens has become less sporadic and of greater interest, especially with the development of more excavations and the use of new methods. The European Mesolithic has been one of the favored time periods among researchers, mostly because of the challenges that it represents: it was marked by important economic, technological, and social changes that accompanied the last hunters-gatherers in Western Europe, where the Mesolithic shellmiddens of Muge, central Portugal, are located (Bicho 2009; Bicho et al. 2010).

Without a doubt, the Mesolithic shellmiddens of Muge, famous for their human burials, had a great influence on the growth of Portuguese archaeology. Along with artefacts like lithics and faunal remains, the estimated 300+ skeletons from this multisite complex makes this one of the most numerous and important collections in the world for the study of Mesolithic society (Bicho et al. 2010; Figueiredo 2012; Umbelino 2006). Since their discovery, the work at Muge has been diversified (e.g. Cardoso and Rolão 1999/2000; Corrêa 1933, 1934, 1936; Detry 2007; Gonçalves 2009; Monteiro 2012; Newell et al. 1979; Paula e Oliveira 1889; Pereira da Costa 1865; Ferembach 1974; Ribeiro 1867, 1884; Roche 1951, 1954, 1957; Roche and Ferreira 1967; Rolão 1999; Rolão et al. 2006a, b; Umbelino 2006), but, despite this, we do not know much about the symbolic value of these burials. Although anthropological studies have been at the forefront of the Muge research, the archaeological record has never been properly explored or analysed, which could bring a greater understanding of these Mesolithic populations (Figueiredo 2012). The aim of this paper is to review the available data on the burials and funerary practices and also present new results from recent field work to show how the new methodology and technology applied can change the perception of funerary practices.

The Muge shellmiddens

The Muge shellmiddens, discovered by Carlos Ribeiro in 1863 (Pereira da Costa 1865), are located in Santarém, central Portugal, on the shores of the Tagus River (Figure 9.1). In this area there are more than ten Mesolithic shellmiddens, but unfortunately only two still exist today: Cabeço da Amoreira and Cabeço da Arruda, the former of which is still under excavation. The others were destroyed in the past, though some were partially excavated (Umbelino 2006). In general, these shellmiddens can be described as very large sites (over 2500 m2 each and between 40 and 80 meters in diameter and 3 to 4.5 meters thick) and located close to the edge of the river margin. They also contain vast quantities of marine and estuarine mollusc shells, disposed as a mound, that display a complex stratigraphy comprising of many archaeological layers. These sites are also marked by the presence of habitat features (e.g. hearths, post-holes, pits) and a burial area that are not far from each other (Bicho and Gonçalves in press; Roche 1954, 1972). The two existing mounds (Cabeço da Amoreira and Cabeço da Arruda) are covered by a rock/pebble, human-made horizon that has been interpreted as a way of protection and preservation of the mound (Bicho 2009; Bicho et al. 2010; Bicho and Gonçalves in press).

The burials – a brief summary of research

The first shellmiddens to be discovered in 1863 were Arneiro do Roquete, also known as Ribeira da Sardinha, and Cabeço da Arruda (Cardoso and Rolão 1999–2000). In that same year, while excavating Cabeço da Arruda, Ribeiro located several other sites: Moita do Sebastião, Cabeço da Amoreira and Fonte do Padre Pedro (Cardoso and Rolão 1999–2000; Rolão 1999). In 1865, Pereira da Costa published the first results from these sites, referring to the discovery of a burial area with at least 45 skeletons and the existence of a significant collection of bone tools, fauna, and lithic artefacts. Once again, in 1884, Ribeiro refers to the presence of more than 120 skeletons in total from Cabeço da Arruda and Moita do Sebastião (Ribeiro 1884). Five decades later, in the early 1930’s, a new series of excavations led by Mendes Corrêa (1936) began, resulting in the discovery of several habitat structures and a dozen more burials. In 1937, he also carried out excavations at Cabeço da Arruda, where around twelve more skeletons were discovered (Rolão 1999). In 1952, Veiga Ferreira and Jean Roche began several excavations at Moita do Sebastião, Cabeço da Amoreira, and Cabeço da Arruda, which lasted for several years (Cardoso and Rolão 1999–2000). Another 33 burials were found at Moita do Sebastião (some were collective burials) (Figure 9.2), along with structures (hearths, post holes and storage pits, all in the base of the shellmidden) (Roche 1954, 1972). At Cabeço da Amoreira they also found seventeen more burials and more than ten skeletons at Cabeço da Arruda (Roche 1972). In 2001, while carrying out new excavations at Cabeço da Amoreira, Rolão and colleagues discovered new skeletons (Roksandic 2006). Their aim was to provide more information about the spatial organization of the site and its social organization. Since 2008, Cabeço da Amoreira has been excavated by a team led by N. Bicho within a multidisciplinary project funded by the Portuguese National Foundation (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia).

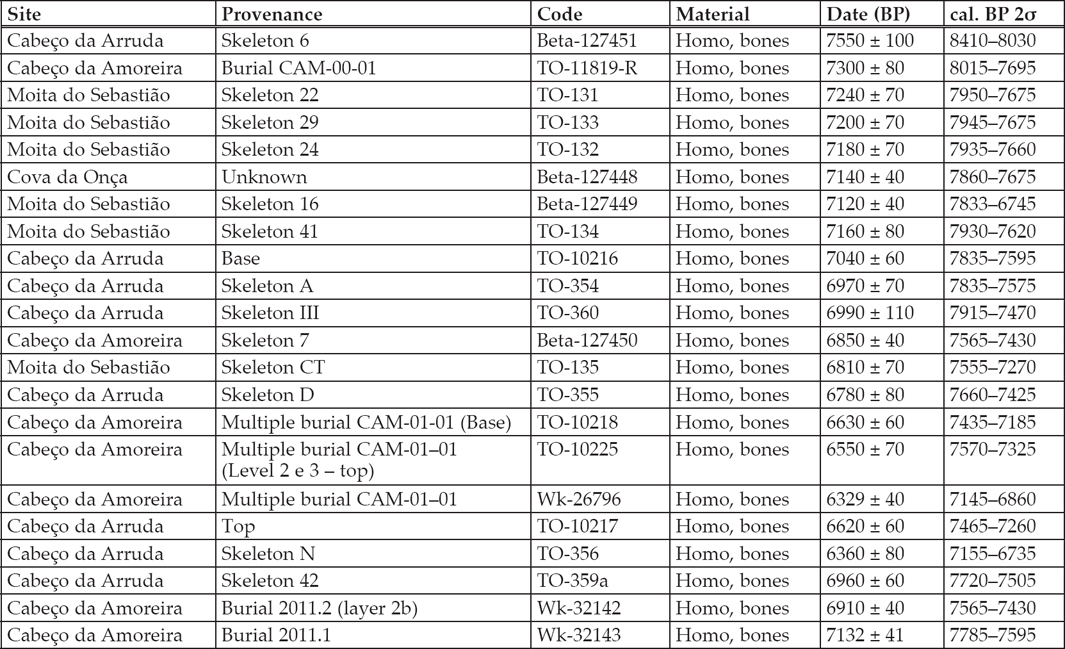

Most of the Muge burials seemed to have been placed at the base of the shellmiddens, although some were found in the upper layers, as we can see in Cabeço da Amoreira and Cabeço da Arruda (Bicho and Gonçalves in press). Regarding the chronology, the Muge skeletons mostly dated between 7900 and 7250 cal BP, but there are rare older or younger dates (see Table 9.1) (Bicho 2009; Bicho et al. 2010; Lubel et al. 1986; Umbelino 2006).

Figure 9.2. Burials from Moita do Sebastião, excavated in 1953. Pictures by C. Teixeira (Cardoso and Rolão 1999/2000).

The funerary practices

One of the most solid cases for significant funerary practices is Moita do Sebastião, where the burials appear to reveal the existence of small groups, which could be evidence of an incipient social complexity. At the base of this shellmidden several habitat features were found, such as post-holes and pits (Bicho and Gonçalves in press). In this case, above these features were found several burials: 59 adults and 12 children (Bicho and Gonçalves in press; Roche 1952, 1974, 1989). Reanalysis of published data revealed a pattern that might result from intra-site organisation, perhaps deriving from social hierarchy and division (Bicho and Gonçalves in press). The burials are organized into two groups, which are at a distance of more than ten meters from each other (Figure 9.3). In the northeastern group, 22 burials were identified, varying in gender and age. Shells have been found in eight of them, with some perforated (Theoduxus fluviatilis) and others not (Scrobicularia plana or Ruditapes decussala). Four of these 22 burials contained stone artefacts. In the southwestern group, twelve burials were identified, including one of a child. This burial was the only one with grave goods in this area (various perforated fluvial shells of Theodoxus fluviatilis). This reanalysis allows an understanding of the differentiation between these burials that could reflect a differentiation in the organization of the Mesolithic inhabitants, at least of this shellmidden. But more than that, this pattern reveals the presence of funerary practices that were not identical for every individual of this population (Bicho and Gonçalves in press).

Analysing the records of previous excavations, it is easy to understand that there was never an established pattern regarding the positions in which the bodies were buried or the votive materials. There does seem to be a tendency to deposit the body in the supine position (lying on the back), varying the position of the arms and legs. It is especially common to observe a dorsal decubitus position, with extended arms, flexed knees and the head a little higher than the rest of the body (Figueiredo 2012). Also, individual burials predominate. Although, Roche (1972) refers to a certain tendency to orient the body to the northeast, it is difficult to see a consistent pattern in this.

Table 9.1. Radiocarbon dates from the Muge area. Calibrated using OxCal 4.1, based on IntCal09. DR value of 140±40 (Bicho et al. 2012).

As said before, the new multidisciplinary project at Cabeço da Amoreira includes a methodology and technology that was never applied to these sites. Excavation by natural layers, subdivided in 5 cm thick spits, and 3D plotting of artefacts bigger than 2 cm using a total station are some of the primary differences in field work compared to the previous excavations of the last 150 years. It is, in fact, a long process, but more information has been retrieved and with much more accuracy. This change has been crucial for the understanding of the structure and the occupation of this shellmidden (Bicho et al. 2011). In July 2011, a new burial at Cabeço da Amoreira was found. This individual was a young woman, between 20 and 25 years old. The radiocarbon date gives us a chronology of 7590–7785 cal BP (Bicho et al. 2012). The methodology applied was, without a doubt, fundamental for the reconstruction of this new burial.

By having the precise location of each element, it was possible to identify several well preserved layers of shells, lithics, and animal bones that formed the burial. The main difference between these layers and the ones observed in the rest of the excavated area is that the burial was covered mainly by cockle shells (Cerastoderma edule), with less sand gaper (Scrobicularia plana), which have been analysed by Catherine Dupont (Université de Rennes). So far, we have observed exactly the opposite in the rest of the area that has been excavated since 2008. It is hardly deniable this evidences indicates a precise funerary ritual.

Conclusions

The available studies of the Mesolithic burials from the Muge shellmiddens have been more focused on physical descriptions of the skeletons and other anthropological characteristics, rather than the description of the individual skeleton’s position, or burials as seen in the recent work of Roksandic (2006). Other aspects related to the archeological and cultural contexts are only succinctly referred to. It is essential for the understanding and reconstruction of the burial practices and its importance for these populations, to relate these contexts with the notion of the distribution of the skeletons in the grave and the presence/absence of artefacts, as well as their position. The quality of the records during and after the excavations is obviously essential. These shellmiddens have been periodically excavated since the mid nineteenth century and the methodologies were applied mostly according to the archeological work done at the time. As a result, the quality of documentation has been affected, and is thus a limitation to the reconstruction of this important characteristic of the Muge Valley population. The new methodology applied at Cabeço da Amoreira since 2008 has been essential for a better understanding of the site, and also has great potential for interpreting the funerary contexts and practices, as displayed by the burial found in 2011. This clearly demonstrates that well documented contexts allow for a better reconstruction and interpretation of the burial practices.

Figure 9.3. Plan of Moita do Sebastião area including the burials (after Bicho and Gonçalves in press).

There is considerable diversity in funerary practice across all categories of evidences from Muge sites: different body positions, grave orientation, and the variety of grave goods. But there is some providence of possible funerary practices and symbolic acts, as the former of which is still under excavation seen at Moita do Sebastião, or at Cabeço da Amoreira, with the new discovery discussed above. For now, the only fact easily observed is that these Mesolithic burials are mostly individual, with no defined pattern regarding the position of the body or the artefacts associated to the burial. Nevertheless, the presence of those artefacts, and especially the organisation of the burial area, reveal an intention of interring the dead in a special way.

Bibliography

Bicho, N. (2009) Sistemas de povoamento, subsistência e relações sociais dos últimos caçadores-recolectores do Vale to Tejo. Estudos Arqueológicos de Oeiras 17, 133–56.

Bicho, N., Umbelino, C., Detry, C. and Pereira, T. (2010) The Emergence of the Muge Mesolithic Shell Midden in Central Portugal and the 8200 cal. yr BP Cold Event. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 5, 86–104.

Bicho, N., Casalheira, J., Marreiros, J., and Pereira, T. (2011) The 2008–2010 Excavations of Cabeço da Amoreira, Muge, Portugal. Mesolithic Miscellany 21(2), 3–13.

Bicho, N., Cascalheira, J., Marreiros, J., Gonçalves, C., Pereira, T. and Dias, R. (2012) Chronology of the Mesolithic Occupation of the Muge Valley, Central Portugal: The case of Cabeço da Amoreira. Quaternary International 308–309, 130–39.

Bicho, N., and Gonçalves C. (in press) Back to the Past: The emergence of social differentiation in the Mesolithic of Muge, Portugal. The Eighth International Conference on the Mesolithic in Europe. Santander: Cantabrian International Institute for Prehistoric Research.

Cardoso, J. L. and Rolão J. M. (1999/2000) Prospecções e escavações nos concheiros mesolíticos de Muge e de Magos (Salvaterra de Magos): contribuição para a história dos trabalhos arqueológicos efectuados. Estudos Arqueológicos de Oeiras 8, 83–240.

Corrêa, M. (1933) Les Nouvelle Fouilles a Muge. XVe Congrès International d’Anthropologie et d’Archaeologie Préhistoriques, pp. 1–16. Paris: Librairie E. Nourry.

Corrêa, M. (1934) Novos elementos para a cronologia de Muge. Anais da Faculdade de Ciências do Porto 18, 154–59. Corrêa, M. (1936) A propósito do ‘Homo taganus’. Africanos em Portugal. Boletim da Junta Geral de Santarém. Santarém 6(46), 37–55.

Detry, C. (2007) Paleoecologia e paleoeconomia do Baixo Vale do Tejo no Mesolítico Final: o contributo dos mamíferos dos concheiros de Muge. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa and Universidad de Salamanca.

Ferembach, D. (1974) Le gisement Mésolithique de Moita do Sebastião. Muge, Portugal. Lisboa: Direcção Geral dos Assuntos Culturais.

Figueiredo, O. (2012) Burial Practices in Muge Shell Middens (Portugal): State of the art. In: A. Almeida, A. Bettencourt, D. Moura, S. Monteiro-Rodrigues and M. Alves (eds) Environmental Change and Human Interaction in the Western Atlantic Facade, pp. 165–70 Coimbra: APEQ.

Gonçalves, C. (2009) Modelos preditivos em SIG na localização de sítio arqueológicos de cronologia mesolítica no vale do Tejo. Unpublished Masters dissertation, Universidade do Algarve.

Lubell, D., Jackes, M., Schwacz, H. and Meiklejohn, C. (1986) New Radiocarbon Dates for Moita do Sebastião. Arqueologia 14, 34–36.

Milner, N., Craig, O. E. and Bailey, G. N. (2007) Shell Middens in Atlantic Europe. In: N. Milner, O. E. Craig and G. N. Bailey (eds) Shell Middens in Atlantic Europe. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Monteiro, P. D. (2012) Woodland Exploitation during the Mesolithic: Anthracological study of new samples from Cabeço da Amoreira (Muge, Portugal). CKQ – Estudios de Cuaternario 2, 33–47.

Newel, R., Constandse-Westermann, T. and Meiklejohn, C. (1979) The Skeletal Remains of Mesolithic Man in Western Europe: An evaluative catalogue. Journal of Human Evolution 8, 29–154.

Paula e Oliveira, F. (1889) Nouvelles fouilles faites dans les kioekkenmoeddings de la vallée du Tage (posthumous publication). Comunicações da Comissão dos Trabalhos Geológicos 2, 57–81.

Pereira da Costa, F. A. (1865) Da existencia do Homem em epochas remotas no valle do Tejo. Primeiro opusculo: noticia sobre esqueletos humanos descobertos no Cabeço da Arruda. Lisboa: Comissão Geológica de Portugal.

Ribeiro, C. (1867) Note sur le terrain quaternaire du Portugal. Extrait du bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 2ª série 24, 692–717.

Ribeiro, C. (1884) Les kioekkenmoedings de la Vallée du Tage. Compte Rendu de la IXème Session du Congrès International dÁnthropologie et d’Archéologie Préhistoriques, Lisbonne 1880, pp. 279–90. Lisboa: Typographie de l’Académie des Sciences.

Roche, J. (1951) L’industrie préhistorique du Cabeço d’Amoreira (Muge). Porto: Centro de Estudos de Etnologia Peninsular/Instituto de Alta Cultura.

Roche. J. (1954) Resultats des dernières campagnes de fouilles exécutées a Moita do Sebastião (Muge). Revista da Faculdade de Ciências 4, 179–86.

Roche, J. (1957) Premiere datation du Mésolithique portugais par la méthode de Carbone 14. Boletim da Academia das Ciências de Lisboa 29, 292–98.

Roche, J. (1972) Le gisement Mésolithique de Moita do Sebastião. Muge, Portugal. Lisboa: Instituto de Alta Cultura.

Roche, J. (1989) Spatial Organization in the Mesolithic Sites of Muge, Portugal. In: C. Bonsall (ed.) The Mesolithic in Europe. Third International Symposium, pp. 607–13. Edinburgh: John Donald.

Roche, J. and Veiga Ferreira, O. (1967) Les fouilles récentes dans les amas coquilliers mésolithiques de Muge (1952–1965). O Arquéologo Português 1, 19–41.

Roksandic, M. (2006) Analysis of Burials from the New Excavations of the Sites Cabeço da Amoreira and Cabeço da Arruda (Muge, Portugal). In: N. Bicho (ed.) Do Epipaleolítico Ao Calcolítico Na Península Ibérica. Actas Do IV Congresso De Arqueologia Peninsular, pp. 43–54. Faro: Universidade do Algarve.

Rolão, J. (1999) Del Wurm final al Holocénico en el Bajo Valle del Tajo (Complejo Arqueológico Mesolítico de Muge). Unpublished PhD dissertation, Universidad de Salamanca.

Rolão, J., Joaquinito, J. A. and Gonzaga, M. (2006a) O complexo mesolítico de Muge: novos resultados sobre a ocupação do Cabeço da Amoreira. In: N. Bicho and H. Veríssimo (eds) Do Epipaleolítico ao Calcolítico na Península Ibérica. Actas Do IV Congresso De Arqueologia Peninsular, pp. 27–42. Faro: Universidade do Algarve.

Rolão, J., Joaquinito, J. A. and Gonzaga, M. (2006b) Muge que valorização? In: N. Bicho and H. Veríssimo (eds) Do Epipaleolítico ao Calcolítico na Península Ibérica. Actas Do IV Congresso De Arqueologia Peninsular, pp. 63–68. Faro: Universidade do Algarve.

Umbelino, C. (2006) Outros sabores do passado. As análises de oligoelementos e de isótopos estáveis na reconstrução da dieta das comunidades humanas do Mesolítico Final e do Neolitico/Calcolítico do território português. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Universidade de Coimbra.