11. Animal Magic: The discovery of Upper Palaeolithic Parietal art in Cathole Cave, Gower Peninsula, South Wales

Abstract

The discovery of an engraved cervid, probably a reindeer, in September 2010 within an inland cave known as Cathole on the Gower Peninsula has reaffirmed the presence of hunter/fisher/gatherer communities in this area of Britain during the Late Upper Palaeolithic. The discovery of a probable engraved figure within a niche located at the rear of Cathole Cave suggests that hunter/fisher/gatherer communities used this section of the cave for ritual purposes. The figure, with a clearly defined torso, legs, and antler set, was produced using a flint tool. The contrast between the straightness of the engraved lines and the curved surface of the flowstone into which it has been carved eliminates any possibility that the figure is a chance configuration of natural fractures. The engraving is the first of its kind to be found in Wales and only the second confirmed discovery of parietal art in the British Isles. In April 2011, samples were taken from a secondary mineral deposit – speleothem (stal) – for Uranium Series dating; a section of this deposit stratigraphically overlay the rock art and the surface on which it was engraved, which provided a minimum age for the engraving.

Introduction

Based on the climatic and environmental records, the British Isles has tended to be regarded as an Upper Palaeolithic cultural backwater, with little or no human activity recognised in the archaeological record, especially during the Late Devensian (e.g. Darvill 2010; Wymer and Bonsall 1977). This lack of evidence is due mainly to the fact that most of Britain was covered by an extensive ice sheet between 40,000–12,000 BP, with the glacial maximum occurring around 22,000 cal. BP. Based on oxygen isotope analysis though, this cold stage lasted for around 100,000 years, from 110,000 to 10,000 years ago. The southernmost limit of the Welsh ice margin extended to just a few kilometres north of Cefn Hill, an upland area that extends across much of the Gower Peninsula in South Wales. The landmass in front of the ice margin, which included the present landform of the peninsula and an extensive area of floodplain that is now the Bristol Channel, can be described as permafrost tundra-steppe formed as a result of pro- and periglacial activity (Figure 11.1). During the summer months this landscape would have offered megafauna, such as bison, elk, horse, mammoth and reindeer a rich seasonal feeding ground. It is conceivable that the present coastal zone of South Wales, from the Wentlooge Levels in the east to the rugged hills around Ammanford in the west, also constituted an ideal breeding area for such megafauna during the summer months.

In general terms, and according to Barton (1997) and Lowe and Walker (1997), the climatic and environmental picture is extremely complex. If the engraving, which I believe represents Rangifer tarandus, was created shortly before the formation of a covering stal deposit, then it and the stal probably formed within the Last Glacial Maximum, a period characterised by rapid warming followed by rapid cooling and a consequent resurgence of ice. During this time, the British Isles witnessed changes in the faunal record that place and date the reindeer engraving either during or before the Loch Lomond Stadial.

Prior to the onset of this interstadial, small groups of hunter/fisher/gatherers appear intermittently to have colonised northwestern Europe, moving north and west along the resource-rich valleys. This pioneer phase is based on a limited number of radiocarbon dates that serve to chart these migration channels – albeit tentatively – in chronological terms (Housley et al. 1997). At around 13,000 BP, the climate began to warm, probably eventually attaining temperatures one to two degrees higher than present. Based on what amounts to a limited archaeological assemblage, tangible human reoccupation in Britain appears to commence around 12,600 BP, some 500 years after the colonisation of lands that are now France and Belgium.

Figure 11.1. Current view of the Bristol Channel, looking south-west from Bacon Hole (photograph by George Nash).

Geomorphology of the cave

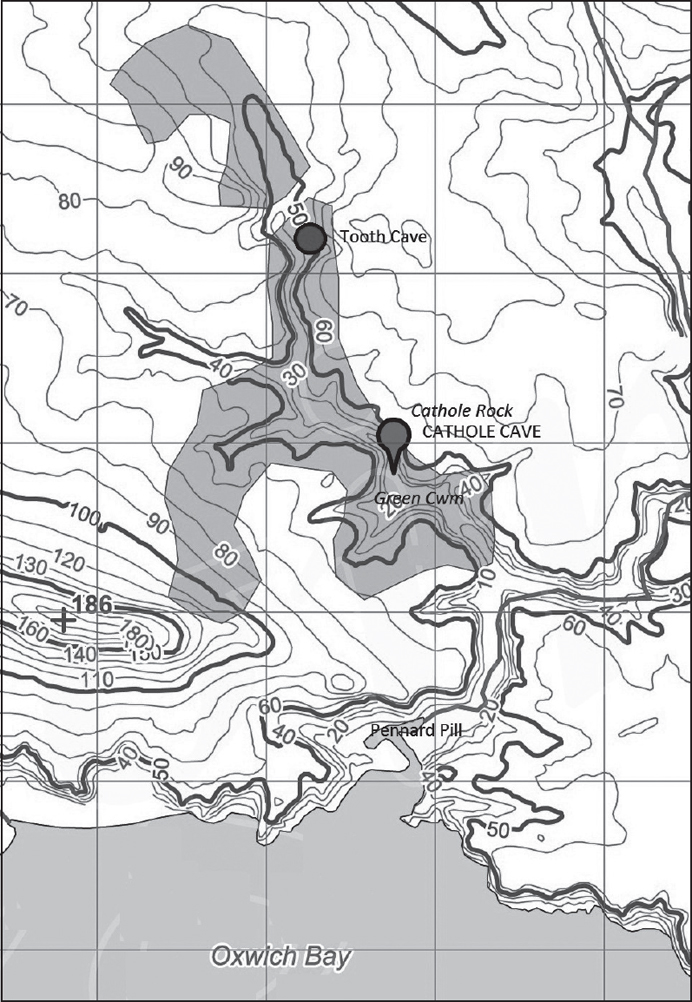

Cathole Cave, in which the reindeer engraving was discovered, stands at about 30 m above sea level on the northeast side of a dry limestone valley, approximately 2 km north of the present coastline (Figure 11.2). It comprises two principal components: a wide passage with a largely flat undulating roof and tall, narrow, joint-influenced rifts that rise several metres above the general roof level (Simms 2011). In plan, the cave has two entrances: the southern entrance leads to a large low-roofed gallery extending about 11 m to the north-east (Figure 11.3). Either side of the main gallery are side-chambers; the northern side-chamber diverts westwards to an antechamber and, beyond this, a second blocked entrance (Oldham 1978). To the northeast of the main gallery is another gallery that extends a further c. 8.3 m (Figure 11.4). This section of the cave is difficult to access and, as far as the author is aware, has never been fully investigated until recently.

In early 2011, the accessible section of the cave was surveyed using 3D laser technology. The purpose of this part of the project was to provide a detailed set of 3D images of the cave (Nash and Beardsley 2013). Subsequent data has enabled the team to produce an accurate floor plan, which was produced using nine laser scan targets that were positioned at key positions within the cave (Figure 11.5). The laser scanning identified a number of natural anomalies that could not be mapped using conventional survey equipment, in particular the contour complexity of the roof and the relationship between the main gallery and the various side niches.

The rugged surface of the roof suggests that the gallery was formed originally in a phreatic environment, i.e. the cave was below the water table and entirely water-filled (Simms 2011). The rock floor of the cave is concealed by a largely unknown depth and type of sediment. Discoloration of the lower part of the walls within the main gallery suggests that the excavations undertaken by Colonel Wood in 1864 removed between 0.7 m and 1 m of this sediment fill.

Figure 11.2. The Location of Cathole Cave, Gower Peninsula.

Figure 11.3. The entrance to Cathole Cave.

Figure 11.4. Small opening leading to the north-eastern section of the cave.

Figure 11.5. Isometric image of the main gallery.

The cave today stands at about 15 m above the valley floor, with the present day phreas probably 5 m or more below this. Hence the cave appears to have formed in a landscape very different from what we see today. The current V-shaped Parkmill Valley probably did not exist at that time, the valley floor being tens of metres higher than today and extending above the current roof level of the cave (Simms 2011). It is possible that the various water-worn relict passages of the cave represent the remnants of a former subterranean river system or subvalley drainage system that was in operation when the valley floor was higher. The subsequent incision of the valley to its present level may be the result of erosion by glacial meltwater runoff during periods when periglacial conditions prevented significant subterranean flow (Waltham et al. 1997). The stream originally flowed through the Parkmill Valley but now resurges at the southern end of the valley, close to the settlement of Parkmill, before reaching the sea. Amelioration of the climate and lowering of the phreas caused the surface flow to sink progressively further north in the valley. The present stream sinks at Llethrid Swallet, located to the north (Ede and Bull 1989). Under flood conditions this swallet may be unable to accommodate the full flow, causing ponding and creating a surface stream that may continue a little further south to sink at older swallets a metre or two higher.

Based on the amount of frost-shattered stone both above and below the surface, the cave entrance may perhaps have extended a further 3–5 m westwards towards a pronounced tongue formed from thermoclastic(?) scree which includes probable spoil from the nineteenth century excavation of Colonel Wood (see below).

Table 11.1. List of species from the Colonel Wood and McBurney excavations.

Excavation history of the cave

Cathole Cave has been the focus of a number of investigations over the past 150 years (summarised in Green and Walker 1991). The first of these was undertaken around the upper cave floor in 1864 by a Colonel E. R. Wood, who recovered a small assemblage of flint tools, metal implements, and pottery dating to the Bronze Age, as well as a significant Pleistocene faunal assemblage (Table 11.1).

In 1958, within the entrance area of the cave, the seasoned archaeologist Charles McBurney of Cambridge University excavated four small rectangular trenches. Recovered from this excavation was a significant lithic assemblage; a limited number of the items being diagnostically similar to flint blades and points found at other Creswellian sites at Creswell Crags and Cheddar. In addition to the Late Upper Palaeolithic assemblage, two tanged Font Robert points were identified as dating to between 22,000 and 28,000 years BP, suggesting a much earlier occupation. This assemblage, together with McBurney’s notes and plans, are archived in the National Museum of Wales (Elizabeth Walker pers. comm.). In his paper, McBurney (1959) gives a useful summary (based on Garrod 1926) of the faunal assemblage recovered by Colonel Wood during his 1864 excavation (reported in Roberts 1887). Despite the lack of any stratigraphic record and the survival of a ‘handful’ of white patinated flints that appear to have been of ‘Creswellian type’, Wood’s excavation did recover a unique faunal assemblage (McBurney 1959, 265). According to Garrod (1926, 65), this assemblage was given to the Natural History Museum (Table 11.1).

According to Garrod’s account, Wood excavated the ‘upper cave’ (main gallery) and she notes that much of the “contents of the cave are mixed” (ibid., 66). Also retrieved from his excavation were a number of Holocene artefacts, including a hammer-stone, a bronze axe (or celt), pottery fragments, and a selection of flint tools, suggesting occupation of the cave for at least 26,000 years. Possibly within this later stratigraphic context were the bones of (domesticated?) goat, pig and sheep, as well as possible evidence of two later prehistoric human burials. However, the Pleistocene faunal assemblage from both Wood’s and McBurney’s excavations is represented principally by extinct fauna (Table 11.1). Despite the absence of chronometric dating of these remains, the presence of such animals indicates a changeable climate, probably coinciding with the interstadial and stadial regimes between 13,000 and 11,000 years BP. Following McBurney’s investigations, a small excavation was undertaken by John Campbell in 1968, which largely substantiated McBurney’s stratigraphic interpretation, although Campbell (1977, 58) did recognize later material, which was probably Mesolithic in date. Campbell opened his trenching to the south of McBurney’s excavation and arguably within an area of peripheral prehistoric activity (i.e. originally within the southern part of the cave entrance). Despite recovering only a limited number of finds, Campbell recognised two important phenomena. First, the various periods (supported by diagnostic flint) appeared to be separated by intermittent thermoclastic activity (frost-shattered scree, suggesting several cold episodes). Secondly, and little discussed in the McBurney report, was the presence of a clear Mesolithic horizon from which a handful of lithics were recovered. Unfortunately, the bone fragments and charcoal recovered from the Lower Open Thermoclastic Scree (LOB) and Middle Sandy Thermoclastic Scree (MSB) layers (both Late Upper Palaeolithic) were then considered to be too small for chronometric dating (ibid., 58).

Figure 11.6. Scratches made by European brown bear, located in a side chamber off the main gallery.

Following a series of incidents in the recent past, the landowner, Forest Enterprise, and the Welsh heritage agency CADW decided in early 2012 to construct a grille across the rear section of the cave, thus protecting the fragile archaeology, the rock art, and the wildlife that currently inhabits it. Prior to constructing the grille, Scheduled Monument Consent (SMC) was required from the Welsh heritage agency CADW as Cathole is designated a Scheduled Monument (SM No. GM 349). As part of the construction methodology for the grille, a linear trench was archaeologically excavated in order to secure the lower section of the grille to the underlying bedrock. The excavation, undertaken by Elizabeth Walker (National Museum of Wales) revealed a shallow stratigraphy of mainly rock-fall and cave earths. Within this stratigraphy were a number of finds that included lithics and faunal remains, possibly representing material that was overlooked from the Colonel Wood excavation.

Discovery and description of the engraved cervid

Against this busy archaeological backdrop, the author and several members of the Clifton Antiquarian Club, Bristol – Christopher Castle and Stephen Tofts – began to explore Cathole Cave in 2007, specifically to look for rock art. The impetus for this was firmly based on the discoveries within several caves on the Mendip Hills, Somerset (Mullan and Wilson 2005). The first visit resulted in the discovery of several European brown bear (Ursus arctos) claw marks that were probably made following a hibernation event, and a possible engraved geometric pattern within an antechamber located north of the main gallery (Figure 11.6). Despite optimism within the team, the general consensus was that the irregular patterning would be difficult to authenticate. This was further supported by several of the scientific analysts who visited the cave in April 2011 and considered the panel to be natural.

During a visit to the cave on September 18th 2010, further exploration resulted in the discovery of an engraved cervid, probably a reindeer, on a vertical panel inside a discrete niche northeast of the main gallery, approximately 10.5 m from the cave entrance. This almost hidden engraving is the first clear evidence of Pleistocene rock art in Wales and only the second discovery of this type and date made in Britain.

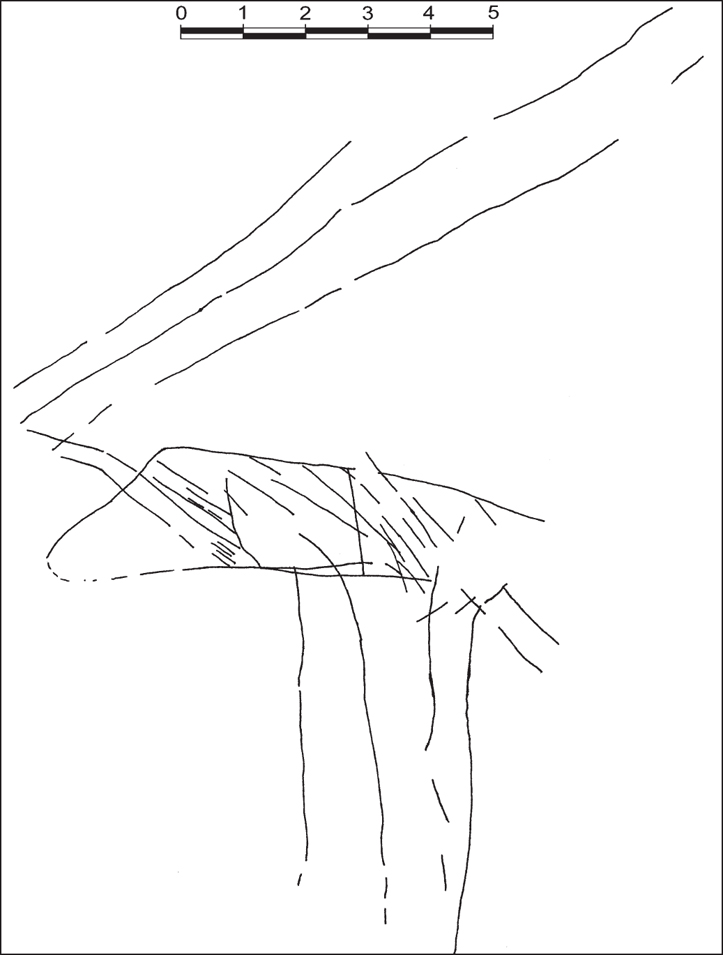

The probable reindeer, measuring approximately 15 x 11 cm, was carved using a pointed flint awl-like tool (Figure 11.7). The figure has a number of characteristics that resemble carved reindeers found elsewhere in northwest Europe. The elongated torso is infilled with vertical and diagonal lines incised into a stabilised speleotherm, which completely covers a smooth water-worn limestone surface. Several internal diagonal lines extend below the lower section of the torso, merging to form three of the four legs, the longest measuring 4.5 cm. Incorporated into the left side of the torso and continuing beyond the head (or muzzle) of the reindeer is a thin rectangular block (the pedicle) on which three lines extend forming the beam and peal of a stylised antler set.

Figure 11.7. Image showing the torso, legs and antler set of the cervid.

The figure is inscribed into a surface of botryoidal calcite flowstone, similar in general character to that found widely through the cave (Nash et al. 2012). This flowstone has a rather opaque, white, almost chalky appearance and little evidence for significant recent deposition. Individual flowstone bosses, or botryoids, are ~10–20mm across and of low relief (<5mm) (Simms 2011). Most of the inscribed lines fall into one of three distinct groupings of straight and sub-parallel lines, with each group at a significant angle to others. All of the lines commence and terminate within the area of flowstone, cut across the botryoidal-textured surface with no apparent effect from it, and do not extend onto the limestone surface beyond it. The straightness of the lines and their confinement within the area of flowstone is particularly strong evidence for a non-natural origin. Any natural fractures, or etched lines, are likely to have been influenced by the curvilinear botryoidal texture of the flowstone to at least some degree, but this does not appear to be the case with any of the lines that together form this figure. Secondly, all of the lines are very shallow and of fairly constant depth and width. Again, this is contrary to what might be expected for natural fractures or etched lines, as exemplified by the numerous small-scale fractures visible on limestone surfaces elsewhere in the cave. From field observations it was impossible to estimate the age of these inscribed lines except in the very broadest terms, but a few pertinent observations can be made. Firstly, the lines are no longer as sharp as if they had just been inscribed, but are encrusted with very fine crystals of calcite that must have been deposited by a very fine water film since the scratches were made. This same finely crystalline texture is also found across the unaltered surface of the flowstone into which the inscription has been made. The left-hand extremity (interpreted as the ‘nose’) has been partly covered by a fairly narrow, vertical strip of flowstone that is subtly different from the flowstone beneath. It has a smoother surface, lacking the fine crystals of the botryoidal flowstone, and has a faint greyish tone at the surface and a chocolate-brown layer beneath. This flowstone strip was slightly damp when observed and appears related to a drip point on the alcove roof immediately above, suggesting it may still be active. The two distinct layers suggest a significant change in percolation water chemistry during its growth, which could reflect a change in the extrinsic environment (if early- or pre-Holocene) or land use (if mid-Holocene or later).

Following the discovery, the authors undertook the task of recording the reindeer. Due to the fragility of the engraving and the surface on which it was engraved, no direct contact tracing was made. Furthermore, the confined space of the niche prevented conventional cameras from being used and instead a series of overlapping images were thus stitched and a tracing made (Figure 11.8).

Its concealed location within a tight niche in the inner section of the cave is, again, not uncommon in terms of Western European Pleistocene rock art; its discreteness suggesting a personalised shrine. The predominance of the Creswellian lithic assemblage initially suggested the reindeer may be contemporary, thus dating to between 12,000 and 15,000 cal. BP.

Dating the engraving

Following the initial discovery and verification process, members of the NERC-Open University Uranium Series Facility extracted samples from the surface on which the engraving was made in April 2011, together with a sample from a section of flowstone covering part of the reindeer’s muzzle. A single date of 12,572 ± 600 years BP was obtained from the overlying flowstone, suggesting a minimum age for the engraving (Nash et al. 2010, 2012). A further flowstone sample was taken from left of the muzzle in July 2011 and results give a similar minimum age of 14,505 ± 879 years. This sample provides corroborative evidence of the age and confirms the absolute youngest age for initial flowstone development. Two other samples exhibited open system behaviour with some clay contamination, and did not yield ages.

Figure 11.8. Tracing of the stylised reindeer, from stitched digital imagery (traced by George Nash).

The 12,572 ± 600 BP date arguably coincides with a period of climatic amelioration in the British Isles, falling between the warm conditions of the Windermere Interstadial and the 1,000 year cold snap of the Loch Lomond Stadial, commencing around 11,000 BP. At its maximum, and based on coleopteran remains, average annual temperature during this cold phase was between minus 10 and 12 degrees centigrade. At this time, human settlement activity appears to have extended only as far north as the Loire Valley in central-western France; artefact evidence elsewhere is limited. Following the abrupt onset of climatic amelioration around 13,000 BP, groups of hunter/fisher/gatherers began to utilise this somewhat hostile landscape, seasonally occupying many of the caves that formed within the frequent limestone outcrops along the Gower Peninsula. In re-evaluating Gough’s Cave in Cheddar Gouge, Jacobi and Higham (2009, 1903) have collated a series of chronometric dates that chart the initial occupation of the site through to its abandonment; it is probable, based on similar diagnostic flint tools and faunal remains that human activity at Gough’s Cave and Cathole are roughly synchronous.

Allen and Rutter (1948), Rutter (1949) and, later, Green and Walker (1991) recognise at least 31 caves on the Gower that potentially have a Palaeolithic presence, many of which contributing to an extensive Pleistocene faunal assemblage. Garrod (1926), Campbell (1977) and Stuart (1982) have identified the presence of arctic fox, brown bear, elk, horse, mammoth, red deer, red fox, wild cattle, and wolf in South Wales during the Windermere Interstadial. Despite the disappearance of mammoth at around 12,000 years ago (probably as a result of mass extinction, or due to so-called overkill), reindeer, a species sensitive to climatic conditions, disappeared during the Windermere Interstadial, but returned around 11,000 cal. BP, prior to and during the onset of the Loch Lomond Stadial, which established a more favourable climate dominated by colder, dryer conditions (Stuart 1982). By around 10,000 BP this tundra-loving species appears to have migrated northwards, beyond the current shoreline of the British Isles, seeking cooler climes. The stylistic characteristics, such as muzzle shape, antler set and infilling of the torso, are not uncommon, with pecked reindeer engravings found along the fjords of central, southern and western Norway. However, I would stress that I am not making any direct association between the Gower discovery and Norwegian hunter/fisher/gatherer rock art. Its location, hidden within a tight niche in the inner section of the cave, is again not uncommon in terms of the Pleistocene rock art of southwest Europe, its discreteness suggesting a sacred place and a personalised shrine.

Conclusion and contextual considerations

It is indeed a rare occurrence for Pleistocene rock art to be discovered within the British Isles. Prior to the 2010 discovery in South Wales, only two other discoveries had been made, at Church Hole and Robin Hood Caves, Creswell Crags, on the Derbyshire/Nottinghamshire border in April 2003 (Bahn and Pettitt 2009) and a possible mammoth engraving at Gough’s Cave in Cheddar Gorge, Somerset (Mullan et al. 2006). The Creswell figures are considered to be Europe’s most northerly Palaeolithic rock art. This discovery included a small number of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic engravings and bas-relief figures, including a bison, red deer and several avian species. Several of these engravings were stratigraphically overlain by a thin veneer of calcium carbonate flowstone and were ascribed a minimum age of 12,800 BP using the Uranium Series disequilibrium dating method (Pike et al. 2005). Several of these figures, including the red deer, used the natural topography of the cave wall to construct or enhance various parts of the animal; a common theme running throughout European Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic rock art.

Associated with the Creswell discovery, and recovered from other nearby caves within the gorge, were a number of Upper Palaeolithic mobile artefacts discovered during the course of late nineteenth and early twentieth century excavations (see Bahn and Pettitt 2009). These included Creswell’s infamous horse, that had been carved on a piece of rib-bone and discovered in 1876, and a bird-like head on a human torso which had been carved on a piece of bone from a woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis), a species considered to have become extinct in Britain by around 15,000 BC. The presence of these exotic artefacts, along with a handful of other portable ‘valuables’ from other Upper Palaeolithic core areas of Britain, including perforated shell and stone made for garment decoration, necklaces and pendants, is set against a backdrop of sometimes rapid climatic amelioration.

Prior to the Creswell discoveries, there had been several false dawns, where Upper Palaeolithic rock art had been discovered and authenticated but later rejected. One of these so-called discoveries occurred at Bacon Hole on the Gower Coast in 1912, when experts of the day – the French verifier, Abbé Henri Breuil, and W. J. Sollas – reported in The Times (14th October) the discovery of ten parallel red streaks of haematite within one of the recesses of the cave. The Times reported it as ‘the first example in Great Britain of prehistoric cave painting’. However, this discovery turned out to be either natural haematite secretions or paint, possibly from a sailor merely cleaning his brushes (Bahn et al. 2003)!

A second discovery, in the Wye Valley of South Herefordshire in 1982, was claimed as Britain’s first representative Palaeolithic rock art and included the outline of a bison and a red deer, amongst other animals, from Cave 5615, located high above Symond’s Yat. The discovery was duly reported in the popular press and later the academic world but lacked any expert validation and, following a series of personal attacks, rebuttals and a confession or two, the discovery was soon rejected (Sieveking 1982; Sieveking and Sieveking 1981).

Placing the engraving into a wider context

Based on previous investigations in and around the site over the last 150 years, the cave can be considered one of Wales’ most important Upper Palaeolithic sites, with a potential archaeological sequence extending, albeit intermittently, over a period of some 25,000 years. The predominantly lithic and faunal assemblages from the Wood, McBurney, and Campbell excavations offer clear evidence of human activity extending from the Late Upper Palaeolithic into the succeeding Mesolithic and later prehistoric periods (Campbell 1977; Garrod 1926; McBurney 1959). How then does the engraved cervid fit into the overall sequence and are there any assumptions to be made concerning the landscape in which it lived and that of the artist?

The disappearance and subsequent return of the reindeer within the palaeoenvironmental record creates an interesting discussion point, in that the stal covering the engraving has been dated to 12,572 ± 600 years BP (CH-10 GHS2) and 14,505 ± 879 years BP (CAT 11 #4). If it is accepted that reindeer inhabited the tundra landscape at around 13,000 BP and before, and again during the Loch Lomond Stadial (between 10,000 and 11,000 BP), can one also suggest a presence here during the Windermere warming phase, or is it simply a case of mistaken identity and the Gower engraving actually represents another cervid, perhaps a red deer or elk? Certain attributes, such as the shape of the muzzle, the pedicle and brow tine (lower section of the antler set), and the shape of the torso, strongly suggest a reindeer, although it could be argued that similar attributes characterise carvings of elk, another cold-environment animal. If the confirmed date of the stal is accepted and the assumption made that whatever underlies it is earlier, the identification of the engraving as a reindeer is almost certainly correct. Clearly, the same could have been said if the stal had returned a date prior to the onset of the Loch Lomond Interstadial.

The pioneering work of D. Q. Bowen (1980) and Roger Jacobi (1980) spreads considerable light on the environment of South Wales and the Bristol Channel at this time. Bowen, reporting on the pollen sequence from the Campbell excavation in 1968, reveals systematic environmental and climatic changes that are clearly synchronous with the chronostratigraphy of Pollen Zones I, II and III. Pollen Zone I, denoting the appearance of thermophilous trees, appears to coincide with Creswellian artefacts recovered from Campbell’s excavation. Pollen Zone II sees a rise in Betula, suggesting the climate is undergoing a gradual amelioration. A range of tundra flora characterises Campbell’s Pollen Zone III, which thus represents the onset of the Loch Lomond Interstadial.

Despite the complexity of this small segment in early prehistoric time, it is probable that the engraving originates from a period when park tundra occupied the proglacial landscape (i.e. before 13,000 BP). The question is how far back before this date (or the dated stal)? As stated earlier, the dating of the stal that overlies part of the cervid provides a stratified minimum date. We know from the artefact record that several Font Robert points were recovered from the Wood excavation. The presence of such artefacts suggests that between c. 22,000 and 28,000 BP hunting communities were at the extreme edge of their geographic range and were using this and other caves within the area. Could the engraving belong to this period? Although I am rather sceptical of this possibility, one cannot dismiss the recent changes in chronometric dating to the so-called Red Lady of Paviland, a male burial that was excavated by the celebrated geologist William Buckland in 1823 at Goat Hole Cave. Since Kenneth Oakley’s initial date of 18,460 ± 340 BP on this skeleton made during the 1960s, a reassessment in 1989 and 1995 has pushed the date of the burial further back to 26,350 ± 550 BP (OxA-1815) (Aldhouse-Green 2000; Aldhouse-Green and Pettitt 1998). In 2007 and 2009 further chronometric dating on the remains has confirmed a date of around 29,000 BP and 33,000 BP respectively (Jacobi and Higham 2008). This is at a time when the cave and much of the current Gower coastline was 120 km inland and sea-level around the British coastline was around 35–50 m lower than present. One must consider that the three postulated dates represent three very different landscapes and palaeoclimatic regimes. Moreover, and in hindsight, one cannot truly rely on dating alone especially as there is a significant deviation of at least 16,000 years between the first and final dates on the Paviland burial.

Either way, the reindeer with its minimum date probably signifies a landscape and climate that is alien to what we witness currently. Although one cannot tie down a terminus post quem date for this engraving, the dated stal covering part of it does place this animal in terms of environment to a period in time that was very cold and an open permafrost landscape that was probably devoid of trees. Despite the harness of this landscape, one member of a mobile hunter-gatherer community was inspired to make his or her discrete mark onto the back wall of a cave in South Wales, some 12 to 13,000 years ago.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Cathole team – Peter van Calsteren, Louise Thomas and Michael Simms for their input and to Elizabeth Walker from the National Museum of Wales for support during the fieldwork element of the project. Thanks also to the team of verifiers who came to Cathole in early 2011; Nick Barton, Simon Colcutt and Robert Layton. Finally, a debt of gratitude to Christopher Castle, Stephen Tofts and Barry Lewis who were initially involved in exploring the cave in 2010 and who commented on this paper.

Bibliography

Aldhouse-Green, S. (2000) Paviland Cave and the ‘Red Lady’: A definitive report. Bristol: Western Academic and Specialist Press Ltd.

Aldhouse-Green, S. and Pettitt, P. (1998) Paviland Cave: Contextualizing the ‘Red Lady’. Antiquity 72, 756–72.

Allen, E. E. and Rutter, J. G. (1948) Gower Caves. Swansea: Welsh Guides.

Bahn, P. and Pettitt, P. (2009) Britain’s Oldest Art: The Ice Age cave art of Creswell Crags. London: English Heritage.

Bahn, P. G., Pettitt, P. and Ripoll, S. (2003) Discovery of Palaeolithic Cave Art in Britain. Antiquity 77 (296), 227–31.

Bowen, D. Q. (1980) The Pleistocene Scenario of Palaeolithic Wales. In: J. A. Taylor (ed.) Culture and Environment in Prehistoric Wales: Selected essays, British Archaeological Reports British Series 76, pp. 1–12. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Campbell, J. B. (1977) The Upper Palaeolithic of Britain: A study of man and nature in the late ice age. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Caseldine, A. (1990) Environmental Archaeology in Wales. Lampeter: St David’s University College.

Darvill, T. (1987) Prehistoric Britain. London: Batsford.

Ede, D. P. and Bull, P. A. (1989) Swallets and Caves of the Gower Peninsula. In: T. D. Ford (ed.) Limestones and Caves of Wales, pp. 210–16. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hallström, G. (1938) Monumental Art of the Stone Age in Northern Europe 1. Stockholm.

Housley, R. A., Gamble, C. S., Street, M. and Pettitt, P. (1997) Radiocarbon Evidence for the Lateglacial Human Recolonisation of Northern Europe. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 63, 25–54.

Garrod, D. A. E. (1926) The Upper Palaeolithic Age in Britain. Oxford: Clarendon.

Green, H. S. and Walker, E. (1991) Ice Age Hunters. Neanderthals and Early Modern Hunters in Wales. Cardiff: National Museum of Wales.

Jacobi, R. M. (1980) The Upper Palaeolithic of Britain With Special Reference to Wales. In: J. A. Taylor (ed.) Culture and Environment in Prehistoric Wales: Selected essays, British Archaeological Reports British Series 76, pp. 15–100. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Jacobi, R. M and Higham, T. F. G. (2008) The ‘Red Lady’ Ages Gracefully: New ultrafiltration AMS determinations from Paviland. Journal of Human Evolution 55, 898–907.

Jacobi, R. M. and Higham, T. F. G. (2009) The Early Late-glacial Re-colonization of Britain: New radiocarbon evidence from Gough’s Cave, southwest England. Quaternary Science Reviews 28, 1895–913.

Lowe, J. J. and Walker, M. J. C. (1997) Reconstructing Quaternary Environments, 2nd Edition. London: Prentice Hall.

McBurney, C. B. M. (1959) Report on the First Season’s Fieldwork on British Upper Palaeolithic Cave Deposits. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 25, 260–69.

McComb, P. (1989) Upper Palaeolithic Osseous Artefacts from Britain and Belgium: An inventory and technological description, British Archaeological Reports International Series 481. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Mullan, G. J. and Wilson, L. J. (2005) A Possible Mesolithic Engraving in Aveline’s Hole, Burrington Combe, North Somerset. Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society 23(2), 78–85.

Mullan, J. G., Wilson, L. J., Farrant, A. R. and Devlin, K. (2006) A Possible Engraving of a Mammoth in Gough’s Cave, Cheddar, Somerset. Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society 24(1), 37–47.

Nash, G. H. (2012) Brief Note of the Recent Discovery of Upper Palaeolithic Rock Art at Cathole Cave on the Gower Peninsula, SS 5377 9002. Archaeology in Wales 51, 111–14. Nash, G. H. and Beardsley, A. (2013) The Survey of Cathole Cave, Gower Peninsula, South Wales. Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society 26(1), 73–83.

Nash, G. H., van Calsteren, P. and Thomas, L. (2010) Marks of Sanctity: Discovery of rock art on the Gower Peninsula, South Wales. Time and Mind 4(2), 149–154.

Nash, G. H. Van Calsteren, P., Thomas, L. and Simms, M. J. (2011) Rock around the Gower. Minerva: The International Review of Ancient Art and Archaeology 22(6), 22–24.

Nash, G. N., Van Calsteren, P., Thomas, L. and Simms, M. J. (2012) A Discovery of Possible Upper Palaeolithic Parietal Art in Cathole Cave, Gower Peninsula, South Wales. Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society 25(3), 327–336.

Oldham, T. (1978) The Caves of Gower. Privately Printed.

Pike, A. W. G., Gilmour, M., Pettitt, P., Jacobi, R., Ripoll, S., Bahn, P. and Muñoz, F. (2005) Verification of the Age of the Palaeolithic Rock Art at Creswell. Journal of Archaeological Science 32, 1649–655.

Roberts, J. (1887) Cats Hole Cave. Annual Report and Transactions of the Swansea Scientific Society, 15–23.

Rogers, T. (1981) Palaeolithic Cave Art in the Wye Valley. Current Anthropology 22(5), 601–02.

Rogers, T., Pinder, A. and Russell, R. C. (1981) Cave Art Discovery in Britain. The Illustrated London News 6990(269), 31–34.

Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales (RCAHMW) (1976) An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments in Glamorgan. Volume I: Pre-Norman Part I. The Stone and Bronze Ages. Cardiff: HMSO.

Ruddiman, W. F. and Mcintyre, A. (1981) The North Atlantic During the Last Deglaciation. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 35, 145–214.

Rutter, J. G. (1949) Prehistoric Gower: The early archaeology of West Glamorgan. Swansea: Welsh Guides.

Sieveking, G. (1982) Palaeolithic Art and Natural Rock Formations. Current Anthropology 23(5), 567–69.

Sieveking, G. and Sieveking, A. (1981) A Visit to Symonds Yat 1981. Antiquity 55, 123–25.

Simms, M. (2011) Report on a Parkmill Cave, Parkmill Valley, Gower. Unpublished.

Stuart, A. J. (1982). Pleistocene Vertebrates in the British Isles. London: Longman.

Vivian, H. H. (1887) Description of the Park Cwm Tumulus. Archaeologia Cambrensis 4(15), 192–201.

Waltham, A. C., Simms, M. J., Farrant, A. R. and Goldie, H. (1997) The Karst and Caves of Great Britain. Geological Conservation Review Series 12, 358.

Wymer, J. J. and Bonsall, C. J. (1977) Gazetteer of Mesolithic Sites in England and Wales. Council for British Archaeology, Research Report No. 22.