12. Ideology of the Hunt and the End of the Epi-Palaeolithic

Introduction

Projectile points define the chipped stone industry of the south-west Asian pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN; see Table 12.1 for chronology). The tradition originates with the el-Khiam points in the PPNA and develops towards larger forms in the PPNB, which would require blanks from specialised ‘naviform’ cores (Gopher 1994; Kozlowski 2001; Quintero and Wilkie 1995, 25). Their importance is also implied by discoveries in the obsidian sources at Kaltepe, Turkey, where the assemblage exhibits few knapping errors and disproportionately large numbers of cores, suggesting not only craft specialisation, but also production for exchange throughout the Levant (Binder and Balkan-Atli 2001, 9). Given the effort put into their creation, as well as disproportionately large sizes, the projectile points of the PPN appear to have a symbolic value beyond their utilitarian application (Peltenburg 2004, 3). Arrowheads form part of a broader phenomenon of association with hunting and broadly conceived ‘wild things’ that runs throughout the PPN. Perhaps the best known are the reliefs of wild animals at Gobekli Tepe, which, in the excavators’ interpretation, are a part of an “ideology of the wild” (Schmidt 2010). This ideology is traced through the complex of art and artefacts focused on animals and plants that evaded domestication. Can a complex of art and artefacts be described as an ideology? According to White (1959) and Latour (2005), the answer is yes. A set of ideas is always linked into a network of references (White’s locus of culture) and these referents can be material. In this sense art and artefacts are ideology. The importance of the relationship between material culture and the ideological process in the Neolithic is further substantiated by the fact that for the first millennium of the PPN, it is the materiality and not domestication that determines the period (Watkins 2010; Willcox et al. 2008). A question thus presents itself: how come projectile points were such an important part of this materiality?

The PPN arrowhead is an artefact whose form exceeds the requirements of functionality. However, in many places, such as ‘Ain Ghazal, Jordan, they were often found in a broken state that, in the absence of unanimous evidence of endemic violence, implies use in hunting (Rollefson 2004, 2010) and hints that their symbolism was still connected to the function of killing animals. We also know that they took hold first in areas where gazelle were frequently hunted (see below). Therefore, some of the answer may lie in how the relationship between people and gazelle changed at the eve of the Neolithic.

This chapter explores what we need to know to evaluate this belief. Despite ambiguities within the Epi-Palaeolithic record some trends stand out. The Near East as a whole was showing signs of widespread networks early on. Gazelle were found in assemblages throughout these networks, despite the differing geographic contexts. This is interesting, as there are significant differences between gazelle species associated with different areas. Another point of interest is that the projectile point technology emerges in the Sinai and the Negev deserts at the end of the Epi-Palaeolithic, but the dispersal happened only with the onset of the Neolithic. The chapter concludes with an outline of how geographical variability and understanding of time are essential to our understanding of the relationships between humans, gazelle, and lithic technology.

Background: the Epi-Palaeolithic in the Near East

Seventy-five years have passed since Dorothy Garrod’s discoveries of Epi-Palaeolithic remains at Shukba Cave in Wadi an-Natuf (Garrod 1932), but the details of what happened in the Epi-Palaeolithic remain elusive. This is primarily due to its length and scale: ten millennia in an area approaching 400,000 square kilometres (Figure 12.1). This means that the few dozen excavations and surveys conducted to date give us only snippets of information, which may well have missed major historical turns. Nevertheless, there is sufficient evidence to sketch a qualitative baseline of the main trends during the period, at least as far as chronology, lithic assemblages, settlement and mobility patterns, and subsistence are concerned. A list of the sites discussed is provided in Table 12.2.

Figure 12.1. Area of study. The ‘Natufian homeland’ according to Bar-Yosef (1998) is shaded. Sites mentioned in text: 1. Gobekli Tepe; 2. Hallan Cemi; 3. Kortik Tepe; 4. Gollu Dag; 5. Tell Qaramel; 6. Abu Hureyra; 7. Kharaneh IV; 8. Wadi Jilat 6; 9. Wadi Ziqlab; 10. Ohalo II; 11. Jericho; 12. Tor al-Tareeq; 13. Ain Mallaha; 14. Nahal Ein Gev; 15. Hatoula; 16. Abu Salem; 17. Ramat Harif; 18. Shunera X; 19. Wadi Feynan 16 (WF-16).

Archaeological entity |

Approximate onset (kyr BP) |

Approximate termination (kyr BP) |

Kebaran (Early Epi-Palaeolithic) |

21.05 |

16.05–15.55 |

Geometric Kebaran (Middle Epi-Palaeolithic) |

16.05–15.55 |

13.42–12.62 |

Natufian (Late Epi-Palaeolithic) |

13.42–12.62 |

10.15–9.65 |

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A |

10.15–9.65 |

8.7–8.6 |

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B |

8.7–8.6 |

7.58–7.5 |

Table 12.1. Chronological outline of the discussed cultural and temporal entities. Dates from Maher et al. (2011, tables 1 and 4). All dates in kyr cal. BC at 95.6% confidence intervals.

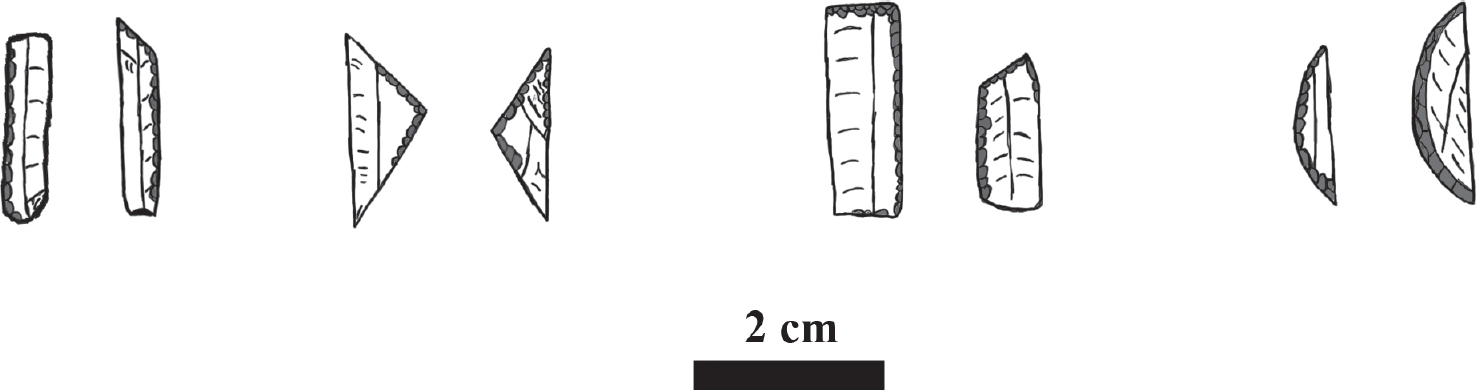

Figure 12.2. Fossiles directeurs for the Epi-Palaeolithic (left to right): bladelettes (Kebaran), triangles, trapezes (Geometric Kebran), lunates (Natufian). Illustration by P. Jacobsson, based upon Pirie (2004, figure 3) and Saxon et al. (1978, figure 2).

The relative chronology of the Epi-Palaeolithic is based on a fossil directeur typo-chronology. This can be divided into three main units: the Kebaran, the Geometric Kebaran, and the Natufian. The Kebaran is defined by the high frequency of bladelets (Figure 12.2a), the Geometric Kebaran on the high incidence of geometric microliths (trapezes and triangles – Figure 12.2b-c), while the Natufian is characterised by lunates (Figure 12.2d; Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen 1989). This typological focus is the function of reliance on survey data and poor preservation of organic materials, which makes the acquisition of large series of radiocarbon measurements difficult. Although absolute dates for the cultural phases are encountered in the literature, a recent review of the evidence by Maher et al. (2011) presents a picture of uncertainty, with the transition boundaries precise to about 500 years. This means that the rapidity of the transformations and their correlation with the climatic changes traceable through palaeo-environmental proxies cannot be evaluated given the currently available data. Furthermore, the sub-division of the main units is still in question, as shown by the recent revision of the Natufian sequence. Originally it was divided into the chronologically distinct early and late Natufian, based on changing sizes and retouch of the lunates. However, an on-going programme of re-dating sites using Bayesian modelling, based upon new series of AMS measurements, suggests that the two entities were contemporaneous on sites within the Mt.Caramel region (Barzilai et al. 2013). Thus division of the Epi-Palaeolithic cannot be specified with confidence beyond early, middle and late, which in the Southern Levant corresponds to the Kebaran, Geometric Kebaran and the Natufian.

The chipped stone that underpins the chronology of the Epi-Palaeolithic is also the backbone of the artefact assemblage. Although the general scheme has been shown not to be applicable throughout the Levant (e.g. Maher et al. 2001 on the lithic assemblage from Wadi Ziqlab), some general propositions appear robust in the face of continuing research (although see Pirie 2004 for a theoretical critique). Microlithic technologies involving relatively simple reduction sequences dominate the assemblages (Belfer-Cohen and Goring-Morris 2002). The versatility of the technology is demonstrated by the possibility of obtaining similar tool types from different production sequences (Richter 2007). Use-wear analyses are still few and have focus mainly on the later Epi-Palaeolithic assemblages, where a variety of functions have been proposed for the lunates (Richter 2007), including use as hunting armatures (Yaroshevich et al. 2010), as has been proposed for the microliths of the earlier Epi-Palaeolithic (Yaroshevich et al. 2013). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that one of the functions of microliths was to act as elements of composite projectile points throughout the period. Unfortunately, the use-wear analyses have been confined so far to the areas west of the Jordan River.

Epi-Palaeolithic settlement was traditionally conceived as a progression towards increasing sedentism (Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen 1989). However, discoveries in the early 1990s undermined this picture. Excavations at Ohalo II have shown the presence of huts and at least bi-seasonal activity in the early Epi-Palaeolithic (Kislev et al. 1992). More recently, evidence of huts has also been encountered in the early Epi-Palaeolithic Azraq basin at Kharaneh IV (Maher et al. 2012a). Therefore, the diachronic ‘progression to sedentism’ model may stem from the research bias toward the late Epi-Palaeolithic (Richter et al. 2011, 96). Incidentally, variations of this model may also overlook some of the geographical variability throughout the region.

Table 12.2. Sites mentioned in the text and referred to in the figures (continued overleaf).

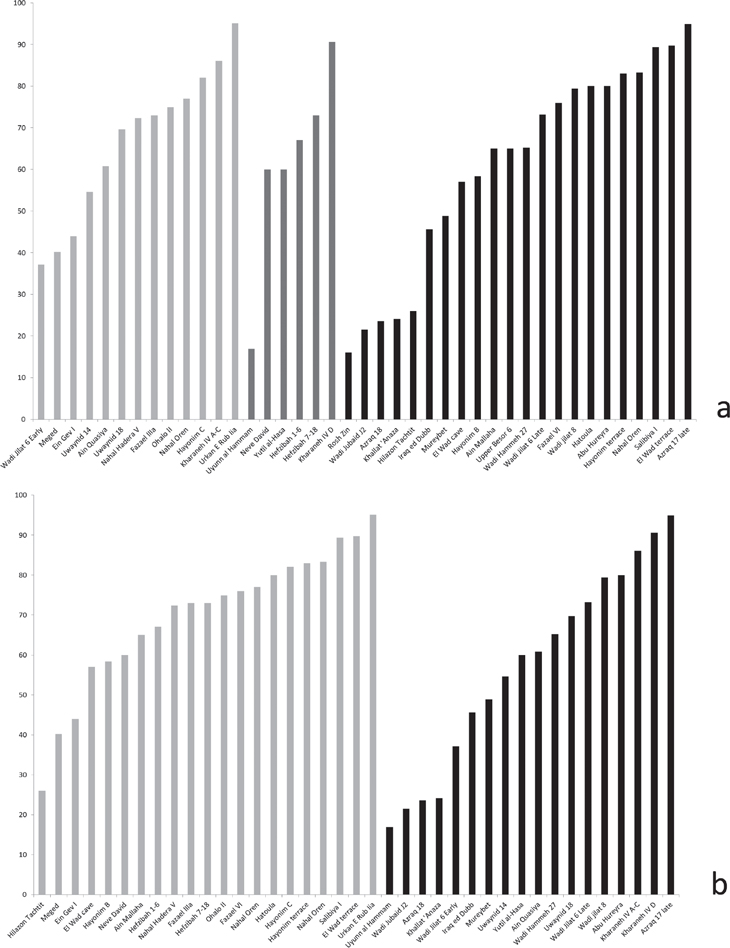

From the perspective of Epi-Palaelithic and Neolithic archaeologies of the area, the Jordan valley constitutes the main geographic division. The valley is flanked by hills on both sides, which extend to the Mediterranean in the west and in the east give way to more subdued terrain and deserts. In the southern Levant the areas west of the Jordan correspond to the ‘Natufian homeland’, or what is the distribution of the Early Natufian lithic industries (Bar-Yosef 1998). Finally there are the areas to the south of the Dead Sea: the Sinai and Negev deserts. The three-fold division corresponds with changes in site sizes (Figure 12.3). Sites as large as 6000 m2 are present on both sides of the Jordan River; however, aggregation sites of more than 10,000 m2 have been identified only to the east (Kharaneh IV and Wadi Jilat 6). Meanwhile, in the Sinai and Negev, the data available indicate diminution by an order of magnitude. It needs to be borne in mind, however, that the intensive surveys of the Sinai and the Negev in the 1970’s and 1980’s resulted in a collection of a vast amount of data from an area undisturbed by modern farming (Goring-Morris 1987). So the frequency of the small sites on distribution maps may be the function of site survival and survey intensity. Nevertheless, present information suggests the following pattern: the areas east and west of Jordan are generally similar in terms of site size; however the east also sees the presence of large sites, while settlements in the Sinai and Negev tend to be much smaller. With only a limited number of sites fitting the picture of ‘sedentisation’ in the late Epi-Palaeolithic, the diachronic trend needs verification (Olszewski 2004), which led Finlayson et al. (2011a) to consider the architectural remains, such as the ‘cult structure’ at Ain Mallaha, as evidence of growing reliance on material culture and not greater sedentism.

Questions of settlement are linked to questions of mobility and exchange. Annual movement of Epi-Palaeolithic people has been modelled by circular and radiating residential mobilities. Circular residential mobility refers to an itinerary of a nomadic cycle, moving from location to location throughout the year. Radiating residential mobility is based on the idea of a semi-permanent base-camp, from which expeditions would take place (Neeley et al. 1998). When applied, this model breaks down in the face of material complexity, as at Tor al-Tareeq (Neeley et al. 1998), or in the face of the chronological developments proposed by Goring-Morris (1987) for the Negev and the Sinai. Given that this model does not hold in the context of hunter-gatherer studies generally (Kelly 1992), keeping it as a baseline reference for the ten millennia of the Near Eastern Epi-Palaeolithic is unjustified.

Figure 12.3. Site sizes: a. by period (light grey = Early; grey = Middle; Black = Late); b. by region (light grey = east of the Rift Valley; grey = Rift Valley and the west; black = Sinai and Negev Deserts).

A consideration of the range of exchange networks throughout the period might be more informative. The sites in the southern deserts are of further interest, as a number of them, such as Shunera 4 or Nahal Seker IV, have produced both Red Sea and Mediterranean shells (Goring-Morris and Bar-Yosef 1987; Pirie 2001) Similar finds characterise the aggregation sites of the Azraq Oasis, where shells from the Indian Ocean have also been found (Richter et al. 2011, 105). The limited strontium analyses from late Epi-Palaeolithic burials indicate a blend of mobility strategies (Shewan 2004), although the paucity of such studies makes it impossible to draw firm conclusions. Nevertheless, recurrence of such findings shows that the supra-regional interaction network, which forms the subject of much Neolithic research in the Near East, may have already begun in the early Epi-Palaeolithic (Maher et al. 2012b).

The field of Epi-Palaeolithic subsistence studies may undergo a revision in the coming years. Until recently it was dominated by the notion of an increasing intensification throughout the period (Davis 2005; Munro 2009; Stutz et al. 2009). On the vegetal side, this hinges on the slow development towards plant cultivation, yet such syntheses are still based on very limited samples and differing definitions of what constitutes cultivation (Olszewski 2004, Willcox et al. 2008). Hence the intensification narrative is substantiated by the increasing diversity of faunal remains, especially microfauna, and its consistency with Flannery’s ‘broad spectrum revolution’ (1969). Under this scenario the hunter-gatherer populations, driven by increasing demographic pressure would begin collecting more wild grasses and be forced to prey on a greater number of species, because the increased hunting would deplete the preferred big game species. Recent syntheses defend the broad spectrum revolution for the Mediterranean zone (Stutz et al. 2009) and there is evidence that this may be the case further afield (Munro 2009). Nevertheless, the hypothesis tying the increasing human population pressure from the end of the last glacial and the diversification of prey still rests on studies of a limited geographical span with poor chronological constraint. The most comprehensive study is that of Stutz et al. (2009), yet it consists of only eight assemblages, of which five belong to the later Epi-Palaeolithic and all are located west of the Jordan River. Through inclusion of sites from the Jordan Valley itself, Humphrey (2012) made an argument that the changing proportion of different species within the faunal assemblages was the function of changing residential practices, rather than an increase in human predatory pressure. Therefore, while we do know that there are changes in the proportions of NISP throughout the period, their interpretation may be ambiguous. Once again this reduces to the question of scale: given the area over which the Epi-Palaeolithic developed, it is unlikely that a single model of subsistence change will be applicable.

In spite of the ambiguities mentioned in the preceding paragraphs, some general observations on the Epi-Palaeolithic hold. The chronology defined by the Kebaran, Geometric Kebaran, and Natufian industries appears robust. The understanding of the lithic material is generally good and indicates a local variability, underpinned by the common theme of microlithisation. There is no unanimous indication of greater sedentism towards the end of the Epi-Palaeolithic and variability in the size of settlements is maintained throughout the region. However, there is a broad geographical difference in that only areas east of the Jordan have confirmed agglomeration sites of more than 10,000 m2. Likewise the Sinai and Negev deserts host much smaller sites than regions elsewhere. There is displacement of seashells throughout the Epi-Palaeolithic, suggestive of migration, exchange networks, or a combination of the two. Finally, in some place, there is a move towards greater prey diversity with time.

There is also one other unambiguous factor: gazelle dominate faunal assemblages throughout the Epi-Palaeolithic and into the beginning of the Neolithic. When did this domination develop? The seminal study by Davis (1991, 2005) observed a steady decrease in game variability from the Mousterian at Biqat Qunetira to the gazelle-dominated Natufian assemblage of Nahal Ein Gev II. Davis interpreted this as the result of predatory pressure triggered by increasing human populations after the Last Glacial Maximum and into the Holocene. The final element of this hypothesis comes from the PPNA Hatoula, which present a growing proportion of juvenile animals. Given that hunters would preferentially choose adult animals, the increased proportion of juveniles was seen as an indicator of the further depletion of game stocks.

Against Davis’ hypothesis, one can amass observations from throughout the territories of modern Syria, Israel, and Jordan. For example, at Abu Hureyra the high proportion of juvenile animals was interpreted in terms of hunting techniques, rather than increased pressure on the gazelle population (Legge and Rowley-Conwy 2000). Furthermore, high proportions of juveniles have also been encountered throughout the early and middle Epi-Palaeolithic at Kharaneh IV and Wadi Jilat 6 (Martin et al. 2010). A more general overview shows no apparent trends in changing gazelle frequencies, neither in time, nor location in terms of the east/west division (Figure 12.4). This implies that there is no evidence for an increase in pressures on gazelle populations on a supra-regional scale in the Epi-Palaeolithic itself. This inverts the question: how come the practice is maintained in some form or another throughout such an expanse of time and space?

Gazelle and people

Hunting and meat consumption are a potential contributor to the maintenance of a human society. This is because of the nutritional properties of meat, as well as the situations created in the context of the hunt. Meat is rich in glutamate, which is a good source of amino acids, as well as a substrate for the production of the neurotransmitter glutamine (Smith and Wilmore 1990). Given its importance, our sense of taste has evolved sensitivity towards it (Yamaguchi and Ninomiya 2000). Furthermore, glutamate was shown to lead to mood improvements (Mosel and Kantrowitz 1952; Young et al. 1993). However, to take advantage of meat as a glutamate source, it needs to be caught first, which in primates is often a collective endeavour. Among chimpanzees, the most successful hunting troupes are those that organise their hunting as a pack, like the Tai (Boesch 2005). Indeed, it is the presence of a large number of chimpanzees, rather than a demand for food, that predicts whether the troupe will set out on a hunt (Watts and Mitani 2002). Thus, the hunts provide opportunities for the chimpanzee troupes to meet at large and redefine their hierarchies (Boesch 2002; Mitani and Watts 2001). Although drawing direct conclusions from primatology is a dubious exercise, the sensual attraction of meat is a general trait encountered in all humans, and hunting in groups is also advantageous to Homo sapiens. Once the group has gathered for the hunt, the meat needs to be redistributed and the whole process becomes a feature that aids the perpetuation of interaction within and between hunter gatherer-bands. However, it is not only the sociality of the hunter that determines the nature of the hunt, but also the sociality of the species hunted.

The Epi-Palaeolithic gazelle hunters could encounter one of two species of Near Eastern gazelle, depending on which side of the Jordan valley they were on. One was the Persian gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa) and the other a smaller mountain gazelle (Gazella gazella). The latter species occupies the hilly habitats within and to the west of the Jordan valley, whilst the former relies on the open areas to the east. Although in modern times a third species, Gazella dorcas, is also encountered, it most likely migrated from Africa with increasing desertification during the Holocene (Yom Tov and Ilani 1987).

Mountain gazelle (Gazella gazella), is the smaller species, weighing between 16.5 and 30 kg (Mendelssohn et al. 1995). It has good sight and can run up to 80 km/h in rugged terrain, although the animals prefer to keep to paths (ibid.). At the same time, they form much smaller groups (mean of 1.68 individuals, see Habibi et al. 1993). Mountain gazelle are stationary: in Saudi Arabia animals from re-introduced populations rarely moved beyond an area of 10 km2 (Dunham 2000). As in the case of Persian gazelle the reproduction rates are high. Between 1948 and 1985 their population in Israel grew from 500 to about 10,000 individuals (Mendelssohn et al. 1995). Also, they will reproduce year-round, given favourable conditions, the most important of which is access to water during lactation (Baharav 1983). Furthermore, they can endure arid conditions by relying on plant water, although this results in defined birthing seasons (ibid.). From the perspective of an Epi-Palaeolithic hunter the mountain gazelle would be more difficult to hunt, as their pack sizes preclude efficiency of mass killings and speed and sight gives an advantage in the context of stalking single animals. On the other hand, their reproduction rates would make them a reliable hunting species.

The Persian gazelle is the larger of the two species, with body weight ranging between 18 and 43 kg (Kingswood and Blank 1996). It avoids cliffs, ravines, and wooded areas, which characterise the regions west of the Jordan River (ibid.). It is known to form herds, which in historical travellers’ reports reached thousands (Legge and Rowley-Conwy 2000), although modern populations in Saudi Arabia and central Asia tend not to exceed groupings of c. a hundred (Cunningham and Wronski 2011; Qiao et al. 2011). Formation of large herds is not a frequent event (mean herd sizes oscillate around 6.5 individuals in central Asia, see Qiao et al. 2011) and their emergence appears to be controlled by rainfall (Cunningham and Wronski 2011) and breeding cycle (Blank et al. 2012). The breeding cycle is characterised by births occurring in March and April (Habibi et al. 1993). The reproduction rate is high; at Bukhara Breeding Centre (Uzbekistan) a population of 44 animals released in 1977 peaked in 1989 at 1224 individuals (Pereladova et al 1998). However, they are also vulnerable to habitat overloading and deterioration of climatic conditions. Following the 1989 peak the Bukhara herd declined to 580 by 1995 (ibid.). This sensitivity is likely linked to the migratory patterns of Persian gazelle. During lactation daily access to water is necessary and at the same time the species cannot sustain itself in areas covered by snow. Taken together, these two factors appear to have been the drivers of the historical migrations (Martin 2000). From the perspective of an Epi-Palaeolithic hunter this means that, if the population of Persian gazelle in the region is large enough and if there are significant geographical variations in water and grazing availability, movement of large numbers of these animals on an annual basis can be expected.

Figure 12.4 Gazelle frequencies as reported NISP percentages: a. by period (light grey = Early; grey = Middle; Black = Late); b. by region (light grey= Rift Valley and the west; black = east of the Rift Valley).

The aggregation sites, as noted above, appear only to the east of the Jordan Valley, within the distribution zone of the Persian gazelle. The faunal assemblages of these sites are gazelle dominated and the age and sex distributions are close to those that would be expected in a living population (Martin et al. 2010). Similar results, coupled with the fact that the age groups were specifically new-borns and juveniles just under one year, were obtained at Abu Hureyra 1. This has been interpreted as evidence of a mass kill strategy, whereby the migrating herd would be run into traps, or off a cliff (Legge and Rowley Conwy 2000). Such practices using specialised ‘desert kite’ structures have been noted from travellers’ tales as late as the early twentieth century (Mendelssohn 1974). However there is nothing that could support the notion of desert kites being constructed before the emergence of state-level societies (Zeder et al. 2013). Nevertheless, local topography, or even indiscriminate patterns in individual hunting, could produce similar results. In the case of Persian gazelle migrations such indiscriminate hunting would not be sufficient to depress the populations – otherwise the species would be wiped out long before the introduction of rifles triggered their demise in the twentieth century. However, what needs to be taken into account is that the migration patterns might have changed with time, as the climatic changes of the Late Pleistocene changed the water availability throughout the Levant, which makes the assumption of the constancy of migration throughout the Late Pleistocene questionable (Martin 2000). Nevertheless, it is plausible to assume that the seasonal availability of large gazelle herds facilitated the formation of large gatherings, which over time led to the formation of scatters in excess of 10,000 m2. Given the diverse origins of the finds found at Kharaneh IV, it is also plausible to assume that these aggregations would be a meeting point for groups usually following itineraries in different parts of the Near East and maintaining different networks further afield.

Persian gazelle is a fairly large ungulate, carrying a significant amount of meat in large herds, which makes it a good prey species. Mountain gazelle offers smaller returns, is more difficult to hunt and occurs in smaller herds. Seen from this perspective, the focus on the gazelle seen at sites west of the Jordan is surprising. Here two alternative hypotheses are possible: the excessive hunting pressure led to the depletion of other fauna, or there was a symbolic value attached to the species throughout the Epi-Palaeolithic of the ‘Natufian homeland’. Given the impossibility of applying mass kill tactics to Mountain gazelle herds, the increased proportion of juveniles at Hatoula may indicate stock depletion and, by proxy, depletion in numbers of other species (Davis 2005). The symbolic interpretation is supported by burials with gazelle horn cores being a recurring feature from the Kebaran Ein Gev I to the Natufian ones at Ain Mallaha (Verhoven 2004). These two scenarios are not mutually exclusive and potentially more complicated factors that we do not yet understand were also at play.

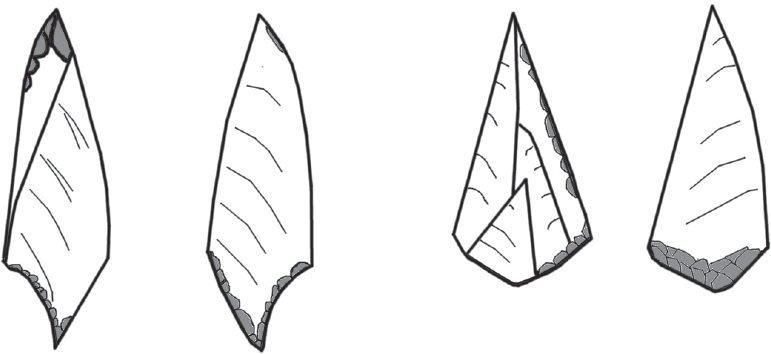

Figure 12.5. Harifian points. Illustration by P. Jacobsson based upon Goring-Morris (1991, figure 17).

Gazelle, people and projectile points

The few archaeozoological studies in the Sinai and the Negev indicate that these regions were found to be gazelle-poor compared to their northern counterparts. It is within this context that the projectile points re-emerge for the first time since the early Epi-Palaeolithic as a defining feature of a local Harifian industry (Figure 12.5; Goring-Morris 1991; Marks 1973). The terminal Epi-Palaeolithic origin is supported by the available radiocarbon dates from the few excavated sites, which places the Harifian towards the end of the eleventh millennium cal. BC (Figure 12.6). The Harifian either dies out or, more likely, transforms into the southern variant of the PPNA encountered at Wadi Feynan 16, which is also gazelle-poor (Finlayson et al. 2011b). The area covered by the Harifian is about 20–30,000 km2, and includes both the low-lying desert areas of the Sinai and the ridges of the Irano-Turanian highland zone. The cultural importance of this geographical difference is substantiated in the settlement record, which alternates between locales with substantial architecture in the uplands (e.g. Abu Salem, see Marks and Scott 1976) and the more ephemeral stations in the Negev (e.g. Nahal Lavan 110, cf. Phillips and Bar-Yosef 1974). Goring-Morris (1991, 209) estimates the Harifian population to have been up to 500 individuals at any one time. While prehistoric demography is riddled with speculation, this falls within the expected size of a dialectic fission-fusion group, as known from modern hunter-gatherer ethnography (Layton et al. 2012, 1238).

Figure 12.6. The chronological extent of the Harifian, constrained by the radiocarbon data from the PPNA WF-16. Data from Goring-Morris (1991). Sites with less than four measurements have been rejected, leaving only Abu Salem and Ramat Harif. All the Harifian radiocarbon determinations are subject to outlier analysis to account for the old wood effect (Bronk Ramsey 2009). This model is based on considering the two sites as uniform phases (Buck et al. 1994) due to lack of sufficient information on site formation and stratigraphy.

The Harifian points were a local development that failed to disperse over the Levant and correlates with low frequencies of gazelle in the faunal assemblage. This is surprising, given that the Harifians were involved in exchange networks reaching as far as Anatolia (obsidian from Gollu Dag was found at Shunera X, see Goring-Morris 1991, 185). Arrowhead dispersal begins only with the onset of the PPNA (Gopher 1994). Within time-scales that are indiscernible by currently available radiocarbon record the projectile point technology developed and dispersed throughout the Levant. Therefore, it is apparent that it took only a few generations for it to become a fixture of assemblages found throughout the Near East. The exceptions are found at the northern extremes of the PPNA distribution on sites, such as Kortik Tepe or Hallan Cemi (Ozkaya 2009), which are almost devoid of gazelle (Arbuckle and Ozkaya 2006). This suggests an association between the projectile point and gazelle hunting during the period when the slow materialization of culture during the late Epi-Palaeolithic has escalated to monumental proportions with the towers of Jericho and Qaramel (Mazurowski et al. 2009), or the enclosures of Gobekli Tepe (Schmidt 2010). Why would this change take place at this time, given that for perhaps as long as half a millennium projectile points were confined to a small area at the edge of the Levant?

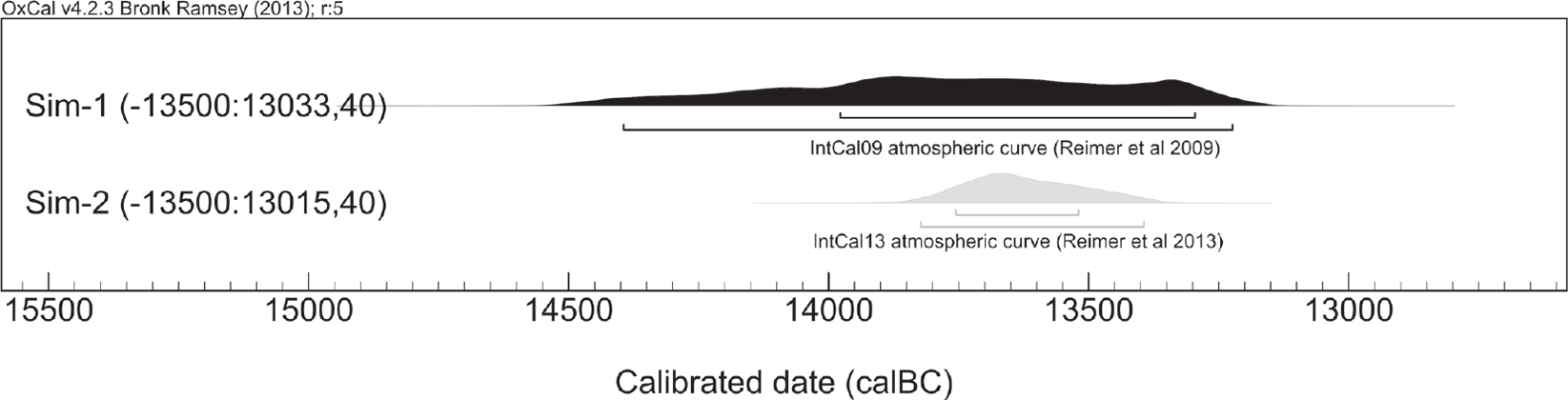

Figure 12.7. A simulation of a 14C determination from the year 13,500 cal. BC calibrated under the curves IntCal 09 and IntCal13.

The simplest hypothesis is that increased human population pressures led to the depression of the gazelle herds, suggested within Davies’ hypothesis. Here the projectile points could be seen as a means of using a material referent to fill in an ideological void. This way, the importance of hunting to human life-ways could be maintained, albeit in changed form. As the projectile points joined the new PPN network, they contributed to the formation of new aggregation sites, such as Gobekli Tepe. Thus, in a way, the hunter-gatherer ideology contributed to Neolithisation. The main problem of the simple scenario is that it relies on the depletion of gazelle throughout the region, which is not unanimously supported by the archaeological evidence.

Any simple scenario of the type discussed above will suffer on account of regional diversity. For this reason, the understanding of the particular communities and the interconnections between them is paramount to a thorough understanding of the processes of change at the end of the Epi-Palaeolithic. It is at this point that the ambiguities in the data begin to constrain our ability to draw inferences, but at the same time we are getting closer to relating these ‘historical’ discussions to particular material record, rather than generalising models of change.

This is because we are no longer trying to extrapolate over the entirety of the Near East and so the interpretations of particular finds are returned to their original contexts. For example, the scenario proposed by Davis, may well be applicable to Hatoula and the surrounding areas. At the same time there is no need to apply this model to Qaramel, or Mureybet, each one of which lies in a different eco-zone, with the local communities involved in very different projects. This does not preclude the impacts of cultural changes throughout the interaction network, or the major environmental changes. It would be unreasonable to pre-suppose that the migration routes of the Persian gazelle would remain unchanged in the face of the Younger Dryas, or the post-Dryas recovery. Therefore, it would be equally unlikely to assume that the itineraries and therefore the practices of the communities hunting the gazelle would remain unchanged. The dispersal of the projectile point technology would have most likely been the result of a series of synchronized local changes, positively feeding back into each other throughout the network.

Unfortunately, we are only in a position to begin the evaluation of such hypotheses for the Epi-Palaeolithic at the moment, as it is only within the past five years that the tools for attaining the kinds of chronological resolution needed to test synchronicity of events became available. Three crucial advances that make this possible are the routine attainment of radiocarbon measurements of less than 50 years, development of an atmospheric calibration curve for the terminal Pleistocene, and advances in dating bio-apatite. The issue of limited precision of individual determinations became apparent during the attempts to date Ohalo II in the early 1990’s. Because all of the measurements had standard errors of over 100 years, what was in the excavators’ opinion a site which lasted a few decades at most, became diffused to a few millennia (Nadel et al. 1995). The improvement of the Pleistocene radiocarbon calibration with IntCal13 is another point of interest. Until 2013, virtually all of the calibration for the period was conducted against a ‘marine curve’ based on Uranium/Thorium dated corals (Fairbanks et al. 2005). This procedure meant that the curve carried over the uncertainties of the U/Th method besides the 14C uncertainties and so the precision of calibrations was much lower (Figure 12.7a, see Reimer et al. 2009). With the advent of IntCal13, there is an addition of the varve record from Lake Suigetsu, which limits the uncertainty from this source (Figure 12.7b, see Reimer et al. 2013). Finally, advances in the dating of inorganic bone fractions (Zazzo and Saliege 2011), might make it possible to use radiocarbon dating for sites which hitherto could not be dated because of lack of surviving collagen, as at Nahal Hadera V (Godfrey-Smith et al. 2003). Until these advances become widely applied, however, our understanding of the processes discussed throughout this paper will be conjectural.

Nevertheless, certain observations seem robust at this point. Firstly, there is strong evidence that gazelle were important to the formation and maintenance of human sociality throughout the Epi-Palaeolithic, although their contribution would have varied in accordance with species ecology. Through this we also know that the Epi-Palaeolithic technology was suitable for hunting gazelle. Secondly, the projectile points of the PPNA dispersed rapidly, but only in the areas with long traditions of gazelle hunting. Therefore, we can make the general assumption that the Epi-Palaeolithic tradition provided the ratchet by which a Neolithic hallmark disperses and reproduces itself. The only way to verify this assumption, however, is to test how it functions in particular local contexts.

Conclusion

This chapter discussed the emergence of an ideological connection between gazelle and projectile points at the end of the Epi-Palaeolithic and the onset of the Neolithic. It was argued that the origin of this process lies in the changing relationships between humans and their surroundings through the Epi-Palaeolithic, although the detail of these transformations is elusive due to the scale of the phenomena in question. Nevertheless, there are some trends, such as correlation of site sizes with different gazelle species present in the area. What is striking is that these animals constitute a substantial part of the archaeozoological assemblages throughout much of the Near East, despite major differences in the ecological background. It is then argued that this long-term tradition was also an important factor in the dissemination of the new projectile point technology, albeit in each region this would probably be the result of different motivations.

Such connections are essential to a thorough understanding of the wider problem of why did hunter-gatherers in some cases choose to Neolithise. In the case of the Near Eastern projectile points, which are closely associated with the Neolithic, it appears that the changes to long-term tradition of gazelle hunting and its associated ideological changes could have played a significant part. The actual processes for how this took place, however, would have been different at each node of the PPN interaction zone. A thorough understanding of the problem will require major advances in Epi-Palaeolithic chronology, which will allow synchronising of discrete events in particular places across this interaction zone.

Acknowledgements.

I would like to acknowledge the Caledonian Research Fund for funding through the period when this paper was drafted. Furthermore, I would like to thank Professors Clive Bonsall and Eddie Peltenburg of the University of Edinburgh for their support during the research behind this paper and comments on the drafts. Finally I would like to thank Ms. Sevvasti Modestou for editorial comments on the drafts.

Bibliography

al-Nahar, M., Olszewski, D. I., Cooper, J. B. (2009) The 2009 Excavations at the Early Epipalaeolithic Site of KPS-75, Kerak Plateau. Neo-lithics 2/09, 9–12.

Arbuckle, B. S. and Ozkaya, V. (2006) Animal Exploitation at Kortik Tepe: An early aceramic Neolithic site in southeastern Turkey. Paleorient 32(2), 113–36.

Baharav, D. (1983) Reproductive Strategies in Female Mountain and Dorces Gazelles (Gazella gazella and Gazella dorcas). Journal of Zoology 200, 445–53.

Bar-Oz, G., Dayan, T., and Kaufman, D. (1999) The Epipalaeolithic Faunal Sequence in Israel: A view from Neve David. Journal of Archaeological Science 26(1), 67–82.

Bar-Yosef, O. (1998) Natufian Culture in the Levant, Threshold of the Origins of Agriculture. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 6(5), 159–77.

Bar-Yosef, O. and Belfer-Cohen, A. (1989) The Origins of Sedentism and Farming Communities in the Levant. Journal of World Prehistory 3(4), 447–98.

Barzilai, O., Rebello, N., Nadel, D., Bocquentin, F., Yeshurun, R. and Boaretto, E. (2013) Early or Late Natufian? New radiocarbon dates for the Natufian graveyard at Raqefet Cave, Mt. Carmel, Israel. Paper delivered at the 7th International Symposium on 14C and Archaeology, Ghent Belgium, 10th April 2013. Abstract booklet available from: <http://www.radiocarbon2013.ugent.be/file/2>

Belfer-Cohen, A. and Goring-Morris, N. (2002) Why Microliths? Microlithization in the Levant. In: R. G. Elston and S. L. Kuhn (eds) Thinking Small: Global perspectives on microlithization, pp. 57–68. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 12.

Betts, A. (1982) A Natufian Site in the Black Desert, Eastern Jordan. Paleorient 8(2), 79–82.

Betts, A. (1991) The Late Epipalaeolithic in the Black Desert, Jordan. In: O. Bar-Yosef and F. R. Valla (eds) The Natufian Culture in the Levant, pp. 217–34. Ann Arbor: International Monographs in Prehistory.

Binder, D. and Balkan-Atli, N, (2001). Obsidian Exploitation and Blade Technology at Komurcu-Kaltepe. In: I. Caneva, C. Lemorini, D. Zampetti and P. Biagi (eds) Beyond Tools. Redefining the PPN lithic assemblages of the Levant. Proceedings of the Third Workshop on the PPN Chipped Lithic Industries, Studies in Early Near Eastern Production, Subsistence and Environment 9, pp. 1–16. Berlin: Ex Oriente.

Boesch, C. (2002) Cooperative Hunting Roles among Tai Chimpanzees. Human Nature 13(1), 27–46.

Boesch, C. (2005) Joint Cooperative Hunting among Wild Chimpanzees: Taking natural observations seriously. Behavioural and Brain Sciences 28(5), 692–93.

Bronk Ramsey, C. (2009) Dealing with Outliers and Offsets in Radiocarbon Dating. Radiocarbon 51(3), 1023–45.

Buck, C. E., Christen, J. A., Kenworthy, J. B. and Litton, C. D. (1994) Estimating the Duration of Archaeological Activity using 14C Determination. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 13(2), 229–40.

Byrd, B. F. (1988) Late Pleistocene Settlement Diversity in the Azraq Basin. Paleorient 14(2), 257–64.

Crabtree, P. J., Campana, V., Belfer-Cohen, A. and Bar-Yosef, D. E. (1991) First Results of the Excavations at Salibiya I, Lower Jordan Valley. In: O. Bar-Yosef and F. R. Valla (eds) The Natufian Culture in the Levant, pp. 161–72. Ann Arbor: International Monographs in Prehistory.

Cunningham, P. L. and Wronski, T. (2011) Seasonal Changes in Group Size and Composition of Arabian Sand Gazelle Gazella subgutturosa marica Thomas, 1897 During a Period of Drought in Central Western Saudi Arabia. Current Zoology 57(1), 36–42.

Davis, S. J. M. (1989) Why Did Prehistoric People Domesticate Food Animals? The bones from Hatoula 1980–1986. In: O. Bar-Yosef and B. Vandermeersch (eds) Investigations in South Levantine Prehistory, pp. 43–59. British Archaeological Reports International Series 497. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Davis, S. J. M. (1991) When and Why Did Prehistoric People Domesticate Food Animals? Some evidence from Israel and Cyprus. In: O. Bar-Yosef and F. R. Valla (eds) The Natufian Culture in the Levant, pp. 381–90. Ann Arbor: International Monographs in Prehistory.

Davis, S. J. M. (2005) Why Domesticate Food Animals? Some zoo-archaeological evidence from the Levant. Journal of Archaeological Science 32(9), 1408–416.

Dunham, K. M. (2000) Dispersal Pattern of Mountain Gazelles Gazella gazella Released in Central Arabia. Journal of Arid Environments 44, 247–58.

Fairbanks, R. G., Mortlock, R. A., Chiu, T.-C., Cao, L., Kaplan, A., Guilderson, T. P., Fairbanks, T. W., Bloom, A. L., Grootes, P. M. and Nadeau, M.-J. (2005) Radiocarbon Calibration Curve Spanning 0 to 50,000 Years BP based on Paired 130Th/234U/238U and 14C Dates on Pristine Corals. Quaternary Science Reviews 24, 1781–796.

Finlayson, B., Mithen, S. and Smith, S. (2011a) On the Edge: Southern Levantine Epipalaeolithic – Neolithic chronological succession. Levant 43(2), 127–38.

Finlayson, B., Mithen, S. J., Najjar, M., Smith, S., Maricevic, D., Pankhurst, N., Yeomans, L. (2011b) Architecture, Sedentism and Social Complexity at Pre-Pottery Neolithic A WF16, Southern Jordan. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108(20), 8183–188.

Garrard, A. N., Coledge, S., Hunt, C. and Montague, R. (1988) Environment and Subsistence during the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene in the Azraq Basin. Paleorient 14(2), 40–49.

Garrard, A. N. and Byrd, B. F. (1992) New Dimensions to the Epipalaeolithic of the Wadi el-Jilat in Central Jordan. Paleorient 18(2), 47–62.

Garrod, D. A. E. (1932) A New Mesolithic Industry: The Natufian of Palestine. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 62, 257–69.

Gilead, I and Marder, O. (1989) Geometric Kebaran Sites in Nahal Rut Area, Western Negec, Israel. Paleorient 15(2), 123–37.

Godfrey-Smith, D. I., Vaughan, K. R., Gopher, A., Barkai, R. (2003) Direct Luminescence Chronology of the Epipalaeolithic Kebaran Site of Nahal Hadera V, Israel. Geoarchaeology: An International Journal 18(4), 461–75.

Gopher, A. (1994) Arrowheads of the Neolithic Levant. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

Goring-Morris, A. N. (1978) Ma’aleh Ziq: A geomteric Kebaran A site in the central Negev, Israel. Paleorient 4, 267–272.

Goring-Morris, A. N. (1987) At the Edge: Terminal Pleistocene hunter-gatherers in the Negev and the Sinai. British Archaeological Reports International Series 361. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Goring-Morris, A. N. (1991) The Harifian of the Southern Levant. In: O. Bar-Yosef and F. R. Valla (eds) The Natufian Culture in the Levant, pp. 173–216. Ann Arbor: International Monographs in Prehistory.

Goring-Morris, A. N. and Bar-Yosef, O. (1987) A Late Natufian Campsite from the Western Negev, Israel. Paleorient 13, 107–12.

Habibi, K., Thouless, C. R. and Lindsay, N. (1993) Comparative Behaviour of Sand and Mountain Gazelles. Journal of Zoology 229, 41–53.

Helmer, D. (1991) Etude de la faune da la phase IA (Natoufien final) de Tell Mureybet (Syrie), fouilles Cauvin. In: O. Bar-Yosef and F. R. Valla (eds) The Natufian Culture in the Levant, pp. 359–70. Ann Arbor: International Monographs in Prehistory.

Henry, D. O., Leroi-Gourhan, A., and Davis, S. (1981) The Excavation of Hayonim Terrace: An examination of terminal Pleistocene climatic and adaptive changes. Journal of Archaeological Science 8, 33–58.

Henry, D. O., Bauer, H. A., Kerry, K. W., Beaver, J. E., and White, J. J. (2001) Survey of Prehistoric Sites, Wadi Araba, Southern Jordan. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 323, 1–19.

Horwite, L. K. and Goring-Morris, N. (2000) Fauna from the Early Natufian Site of Upper Besor 6 in the Central Negev, Israel. Paleorient 26(1), 111–28.

Humphrey, E. S. 2012. Hunting Specialisation and the Broad Spectrum Revolution in the Early Epipalaeolithic: Gazelle exploitation at Urkan e-Rubb IIa, Jordan Valley. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Toronto.

Kelly, R. L. (1992) Mobility/Sedentism: Concepts, archaeological measures, and effects. Annual Review of Anthropology 21, 43–66.

Kingswood, S. C. and Blank, D. A. (1996) Gazella subgutturosa. Mammalian species 518, 1–10.

Kislev, M. E., Nadel, D., Carmi, I. (1992) Epipalaeolithic (19,000 BP) Cereal and Fruit Diet at Ohalo II, Sea of Galilee, Israel. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 73, 161–66.

Layton, R., O’Hara, S. and Bilsborough, A. (2012) Antiquity and Social Functions of Multilevel Social Organization among Human Hunter-Gatherers. International Journal of Primatology 33, 1215–245.

Latour, B. (2005) Re-assembling the Social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Legge, A. J. and Rowley-Conwy, P. (2000) The Exploitation of Animals. In: A. M. T. Moore, G. C. Hillman and A. J. Legge (eds) Village on the Eurphrates. From foraging to farming at Abu Hureyra, pp. 423–71. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Maher, L., Lohr, M., Betts, M., Parslow, C. and Banning, E. B. (2001) Middle Epipalaeolithic Sites in Wadi Ziqlab, Northern Jordan. Paleorient 27, 5–19.

Maher, L. A., Banning, E. B. and Chazan M. (2011). Oasis or Mirage? Assessing the role of abrupt climate change in the prehistory of the southern Levant. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 21, 1–30.

Maher, L. A., Richter, T. and Stock, J. T. (2012a) The Pre-Natufian Epipaleolithic: Long-term behavioral trends in the Levant. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News and Reviews 21(2), 69–81.

Maher, L. A., Richter, T., Macdonald, D., Jones, M. D., Martin, L. and Stock, J. T. (2012b) Twenty Thousand-Year-Old Huts at a Hunter-Gatherer Settlement in Eastern Jordan. PLoS ONE 7(2), e31447. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031447.

Marks, A. E. (1971) Settelement Patterns and Intrasite Variability in the Central Negev, Israel. American Anthropologist 73(5), 1237–244.

Marks, A. E. (1973) The Harif Point: A new tool Type from the terminal Epipaleolithic of the central Negev, Israel. Paleorient 1, 97–99.

Marks, A. E. and Scott, T. R. (1976) Abu Salem: Type site of the Harifian industry of the southern Levant. Journal of Field Archaeology 3(1), 43–60.

Martin, L. (2000) Gazelle (Gazella spp.) Behavioural Ecology: Predicting animal behaviour for prehistoric environments in south-west Asia. Journal of Zoology 250, 13–30.

Martin, L., Edwards, Y. and Garrard, A. (2010) Hunting Practices at an Eastern Jordanian Epipalaeolithic Aggregation Site: The case of Kharaneh IV. Levant 42(2), 107–135.

Mazurowski, R. F., Michczyńska, D. J., Pazdur, A. and Piotrkowska, N. (2009) Chronology of the Early Pre-Pottery Neolithic Settlement Tell Qaramel, Northern Syria, in the Light of Radiocarbon Dating. Radiocarbon 51(2), 771–781.

Mendelssohn, H. (1974) The Development of the Populations of Gazelles in Israel and their Behavioural Adaptations. In: V. Geist and F. Walther (eds) The Behaviour of Ungulates and its Relation to Management, pp. 722–43. IUCN Publication No. 24. Switzerland: Morges.

Mendelssohn, H., Yom-Tov, Y. and Groves, C. P. (1995) Gazella gazelle. Mammalian Species 490, 1–7.

Mitani, J. C. and Watts, D. P. (2001) Why do Chimpanzees Hunt and Share Meat? Animal Behaviour 61, 915–24.

Mosel, J. N. and Kantrowitz, G. (1952) The Effect of Monosodium Glutamate on Acuity to the Primary Tastes. The American Journal of Psychology 65(4), 573–79.

Munro, N. D. (2009) Epipaleolithic Subsistence Intensification in the Southern Levant: The faunal evidence. In: J.-J. Hublin and M. P. Richards (eds) The Evolution of Hominin Diets: Integrating approaches to the study of Palaeolithic subsistence, pp. 141–55. Springer Science + Business Media B.V.

Nadel, D., Carmi, I., Segal, D. (1995) Radiocarbon Dating of Ohalo II: Archaeological and methodological implications. Journal of Archaeological Science 22, 811–22.

Neeley, M. P., Peterson, J. D., Clark, G. A., Fish, S. K. and Glass, M. (1998) Investigations at Tor al-Tareeq: An Epipalaeolithic site in Wadi el-Hasa, Jordan. Journal of Field Archaeology 25(3), 295–317.

Olszewski, D. I. (2004) Plant Food Subsistence Issues and Scientific Inquiry in the Early Natufian. In: C. Delage (ed.) The Last Hunter Gatherers in the Near East, pp. 189–210. British Archaeological Reports International Series 1320. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Ozkaya, V. (2009) Excavations at Kortik Tepe. A new prepottery Neolithic A site in southeastern Anatolia. Neolithics 2/09, 3–8.

Peltenburg, E. J. (2004) Cyprus: A regional component of the Levantine PPN. Neo-Lithics 1/04, 3–7.

Pereladova, O. B., Bahloul, K., Sempere, A. J., Soldatova, N. V., Schadilov, U. M. and Prisidznuk, V. E. (1998) Influence of Environmental Factors on a Population of Goitered Gazelles (Gazella subgutturosa subgutturosa Guldenstaedt, 1780) in Semi-Wild Conditions in an Arid Environment: A preliminary study. Journal of Arid Environments 39, 577–91.

Phillips, J. and Bar-Yosef, O. (1974) Prehistoric Sites Near Nahal Lavan, Western Negev, Israel. Paleorient 2(2), 477–82.

Pirie, A. (2001) Chipped Stone Variability and Approaches to Cultural Classification in the Epipalaeolithic of the South Levantine Arid Zone. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Durham University.

Pirie, A. (2004) Constructing Prehistory: Lithic analysis in the Levantine Epipalaeolithic. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 10(3), 675–703.

Qiao, J., Yang, W., Xu, W., Canjun, X., Liu, W. and Blank, D. (2011). Social Structure of Goitered Gazelles Gazella subgutturosa in Xinjiang, China. Pakistan Journal of Zoology 43(4), 769–75.

Quintero, L. A. and Wilkie, P. J. (1995) Evolution and Economic Significance of Naviform Core-and-Blade Technology in the Southern Levant. Paleorient 21(1), 17–33.

Reimer, P. J., Baillie, M. G. L., Bard, E., Bayliss, A., Beck, J. W., Blackwell, P. G., Bronk Ramsey, C., Buck, C. E., Burr, G. S., Edwards, R. L., Friedrich M., Grootes, P. M., Guilderson, T. P., Hajdas I., Heaton, T. J., Hogg, A. G., Hughen, K. A., Kaiser, K. F., Kromer, B., McCormac, F. G., Manning, S. W., Reimer, R. W., Richards, D. A., Southon, J. R., Talamo, S., Turney, C. S. M., van der Plicht, J. and Weyhenmer, C. E. (2009) IntCal09 and Marine 09 Radiocarbon Age Calibration Curves, 0–50,0000 Years Cal. BP. Radiocarbon 51(4), 1111–151.

Reimer, P. J., Bard, E., Bayliss, A., Warren Beck, J., Blackwell, P. G., Bronk Ramsey, C., Grootes, P. M., Guilderson, T. P., Haflidason, H., Hajdas, I., Hatte, C., Heaton, T. J., Hoffmann, D. L., Hogg, A. G., Hughen, K. A., Kaiser, K. F., Kromer, K. F., Manning, S. W., Niu, M., Reimer, R. W., Scott, E. M., Southon, R. J., Staff, R. A., Turney, C. S. M. and van der Plicht, J. (2013) IntCal13 and Marine13 Radiocarbon Age Calibration Curves 0–50,000 Years Cal. BP. Radiocarbon 55(4), 1869–887.

Richter, T. (2007) A Comparative Use-Wear Analysis of Late Epipalaeolithic (Natufian) Chipped Stone Artefacts from the Southern Levant. Levant 39, 97–122.

Richter, T., Garrard, A. N., Allock, S., and Maher, L. A. (2011) Interaction before Agriculture: Exchanging material and sharing knowledge in the final Pleistocene Levant. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 21, 95–114.

Rollefson, G. O. (2004) Cultural Genealogies: Cyprus and its relationship to the PPN mainland. Neo-lithics 1/04, 12–13.

Rollefson, G. O. (2010) Violence in Eden: Comments on Bar-Yosef’s Neolithic warfare hypothesis. Neo-lithics 1/10, 62–65.

Ronen, A. and Lechevallier, M. (1991) The Natufian at Hatoula. In: O. Bar-Yosef and F. R. Valla (eds) The Natufian Culture in the Levant, pp. 149–60. Ann Arbor: International Monographs in Prehistory.

Saxon, E. C., Martin, G., Bar-Yosef, O. (1978) Nahal Hadera V: An open air site on the Israeli littoral. Paleorient 4, 253–66.

Schmidt, K. (2010) Budowniczowie Pierwszych Swiatyn. Warszawa: Panstwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

Shewan, L. (2004) Natufian Settlement Systems and Adaptive Strategies: The issue of sedentisim and the potential of strontium isotope analysis. In: C. Delage (ed.) The Last Hunter Gatherers in the Near East, pp. 55–94. British Archaeological Reports International Series 1320. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Smith, R. J. and Wilmore, D. W. (1990) Glutamine Nutrition and Requirements. Journal of Prenatal and Enteral Nutrition 14(4), 94S-99S.

Stutz, A. J., Munro, N. D. and Bar-Oz, G. (2009) Increasing the Resolution of the Broad Spectrum Revolution in the Southern Levantine Epipaleolithic (19–12 ka). Journal of Human Evolution 56, 294–306.

Watkins, T. (2010) New Light on Neolithic Revolution in South-West Asia. Antiquity 84, 621–34.

Watts, D. P. and Mitani, J. C. (2002) Hunting Behavior of Chimpanzees at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda. International Journal of Primatology 23(1), 1–28.

White, L. A. (1959) The Concept of Culture. American Anthropologist 61(2), 227–51.

Willcox, G., Buxo, R., Herveux, L. (2009) Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene Climate and the Beginnings of Cultivation in Northern Syria. Holocene 19(1), 151–58.

Yamaguchi, S and Ninomiya, K. (2000) Umami and Food Palatability. The Journal of Nutrition 130(4), 921S-926S.

Yaroshevich, A., Kaufman, D., Nuzhnyy, D., Bar-Yosef, O. and Weinstein-Evron, M. (2010) Design and Performance of Microlith Implemented Projectiles during the Middle and the Late Epipaleolithic of the Levant: Experimental and archaeological evidence. Journal of Archaeological Science 37, 368–88.

Yaroshevich, A., Nadel, D., Tsatskin, A. (2013) Composite Projectiles and Hafting Technologies at Ohalo II (23 ka, Israel): Analyses of impact fractures, morphometric characteristics and adhesive remains on microlithic tools. Journal of Archaeological Science 40(11), 4009–23.

Yom Tov, Y. and Ilani, G. (1987) The Numerical Status of Gazella dorcas and Gazella gazella in the Southern Negev Desert, Israel. Biological Conservation 40, 245–53.

Young, L. S., Rye, R., Scheltinga, M., Ziegler, T. R., Jacobs, D. O. and Wilmore, D. W. (1993) Patients Receiving Glutamine-Supplemented Intravenous Feedings Report an Improvement in Mood. Journal of Parental and Enteral Nutrition 17(5), 422–27.

Zazzo, A. and Saliege, J.-F. (2011) Radiocarbon Dating of Biological Apatites: A review. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 310(1–2), 52–61.

Zeder, M., Bar-Oz, G., Rufolo, S. J. and Hole, F. (2013) New Perspectives on the Use of Kites in Mass Kills of Levantine Gazelle: A view from northeastern Syria. Quaternary International 297, 110–25.