— 6 —

“Don’t shit me just to spare my feelings, Daniel. I’m dead.”

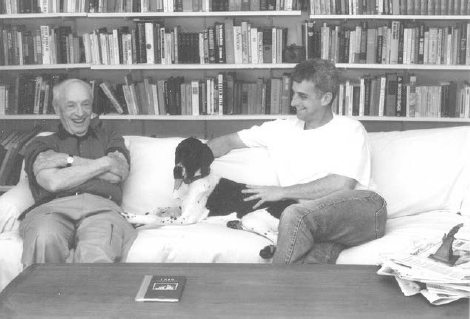

DANIEL BELLOW (SON) AND SAUL BELLOW

I was walking my dogs in the tame little woods at the top of Castle Hill like I do every day here in the middle of life’s journey. It was November, and the dusk was coming down fast. I came to a fork in the trail, and nothing looked familiar. Ahead, I thought I saw the shadow of a giant wolf on the trail, an inky patch in the darkness. A shiver ran all over me, and my dogs bolted for home. I was about to go after them when I saw the old man hastening toward me through the trees.

“Mercy,” I said, for I was sore afraid.

“It is another path that you must take,” he said, “if you would leave this savage wilderness.”

I would have known that voice anywhere. “Pop?”

“Hello, kid.” He gave me that gap-toothed grin. He was dressed for a walk in the country with his mosquito shirt and his old train engineer’s cap and red bandanna and his favorite walking stick I picked for him off a beaver dam in the Adirondacks. I threw my arms around his neck. He felt solid enough.

“What are you doing here? You’re supposed to be dead. Am I dead? I’m wearing shoes. . . .”

In reply, he grabbed my ass and squeezed it hard until I hollered, like he used to do when I was little. There was no way I could have slept through that, and they say the dead lack sensation, but it still felt like a dream, one I had to keep a lid on before it got out of control.

“I have to find my dogs,” I said, trying to cling to what I knew was real.

“They ran off home. Sensible creatures. You always had nice dogs.”

“What about your dog?” I pointed up the hill toward the shadow.

“Oh, she’s not mine. She comes from Hell, was sent above by Envy.”

“Oh. I read about her in a book. You’re not going to let her bite me?”

“I think and judge it best for you to follow me.”

“How come you’re speaking in iambic pentameter?”

“I’ve got Virgil’s old job. Not too shabby, eh?”

“Have you come to take me through the seven circles of Hell?”

“I’m here to take you out to lunch.”

“It’s dinnertime.”

“You took a writing assignment, lunch with your dead famous father.”

“I did. I was procrastinating.”

“So I’m a little late. Are you coming with me, or what?”

Obviously, I had to go. He took me by the hand, and like a little boy I followed, down the trail in the dark, but instead of the railroad tracks at the bottom of the hill we came out on the east side of Amsterdam Avenue at Eighty-Sixth Street.

To judge by the state of the buildings, the style of the taxis, the rich bouquet of garbage, the exhaust, and the disco beat from an upstairs window, I’d say it was about 1979. Pop was suddenly wearing that double-breasted suit with the psychedelic lining he used to like, and a loud tie. I was still in jeans and a T-shirt and my black leather jacket, so I felt comfortable. We walked into Barney Greengrass.

The waiter, tall and stooped, bald with a greasy comb-over and a nose like a toucan, pointed us to a table in the corner. In the court of the Sturgeon King, it could have been anywhere between 1958 and last week, the deli case with its piles of smoked fish, the mysterious wallpaper with scenes of old New Orleans.

“Pop, where are we?” I asked in a low voice, leaning into his ear.

“Barney Greengrass. Don’t you recognize it?”

“Yeah, but how come it’s 1979 outside?”

“We’re in Hell. Take a good look at the waiter.”

The waiter came. “We’ve got some specials today.” He pointed at the spots on the tablecloth. “We’ve got brisket, and tzimmes, and a stuffed pepper.”

“I’ve heard this joke but I’ve never been in it before,” I said. They both ignored me.

“Have the salami sandwich,” Pop said. “They get the good stuff. Best’s Kosher from Chicago. Bring us some of those Strub’s pickles.”

“I’ll have a Cel-Ray, please,” I said. “With ice.” It was a special occasion.

The waiter went away. “Holy shit, it’s Philip Roth.”

“Yes, this is his job,” Pop answered.

“Someone’s got a wicked sense of humor.”

“He’s also married to your mother. She got promoted to Fury last year.”

“So if I went home, three blocks away . . .”

“You’d find Philip Roth living with your mother. His fault, the schmuck.”

“Oh. Okay.”

“There are some things no boy should have to see.”

A change of subject seemed in order. “How’d you get this job, leading middle-aged guys through Hell?”

“My entire life was an audition for this job.”

“What’s Virgil doing?”

“He went back to try his luck again; he made some good films in Japan. Balzac had the job for a while. They need an unbeliever who can tell a story.”

“You can come back?”

“Once every thousand times around the sun.”

“Do you have a wife, too?”

“Mary McCarthy. Edmund Wilson’s ex. You never met her.”

“Yeah, but I read her. That famous line about Lillian Hellman—‘Every word she writes is a lie, including “and” and “the.” ’ ”

“On The Dick Cavett Show. It got her sued.”

“She seems like she could give you a run for your money.”

“She’s got a mouth on her. But she’s a hot lay.”

“This is not your usual taste in ladies, Pop.”

“Hell is here to teach you what you failed to learn in life.”

“Like relations with women?”

“I came up short, as I am told and told again. Also being sweet to children.”

“You could be sweet.”

“Don’t shit me just to spare my feelings, Daniel. I’m dead.”

“Okay. You were an awful, scary monster, but you could be sweet sometimes.”

“When you arrive, you have to watch your whole life on film. Every painful scene, with nothing you can do to make it any better. The movie’s made, and now it’s in the theaters. Above the screen they write: ‘Abandon hope all ye who enter here.’ That’s when you know you’re dead for real.”

“Your whole life? Like, every time you take a leak?”

“Just the highlights, but still it takes five years, eight hours a night. You’re never quite the same.”

“So not quite as bad as being stuck in a hot room with bad décor and two women you can’t screw?”

“Oh, worse than that. Look at Philip.”

“He always looked like that.”

“I’m telling you so you know,” he snapped. “Maybe your last reel won’t be as hard to take as mine.”

The pickles came, in a stainless-steel container on a plate. They were deliciously salty, neither too crisp nor too soft.

“So what do you do all day?”

“Nothing ever happens here in Hell. One day is pretty much the same as the next. The only source of interest is what happens in the world, where things can still be fixed. Everything we see, there’s nothing we can do or say about it. I would have warned you not to trust that crooked business partner of yours, and that other putz who started the magazine just so he could shtup his friends’ wives in hotel rooms. And you remember when I got into your dream and told you not to be afraid to get divorced.”

“Adam laughed when I told him. He said, ‘Pop was never afraid to get divorced.’ ”

Pop chuckled, cocked his head to one side, and smiled an evil smile that somehow included us both.

“Sometimes when we’re together and saying bad things it seems like you’re there with us.”

“I am, but that’s you boys talking, make no mistake.”

“So you can’t act or communicate with us?”

“No. Mostly all I can do is watch helplessly. The wall is very thin, and you can only see through it from this side. Sometimes, when I want a closer view, I come as a dragonfly or a bluebottle.”

“So when we went to marriage counseling with the Magic Mama—”

“The time you nearly got sideswiped by that crazy broad who dropped her brassiere straps for you?”

“And the Mama made me do a dance with my wife and said, ‘Turn around and look over your left shoulder for your father and your grandfather. . . .’ ”

“And give us back the burden of Russian Jewish history.” He began to giggle.

“Please don’t tell me you were both there,” I said.

Pop lost it, throwing back his head and roaring like a jackass. “We might have played along,” he said, “if we hadn’t been laughing so hard.” He wiped his eye. “She said, ‘Those poor men, they had to leave Russia, everything they knew, and come to a strange land. Oy! Oy!’ ” He was in stitches and couldn’t go on.

“I tried to tell her, no one in my family has ever expressed the slightest regret at having to leave Russia.”

“Your grandfather practically had to be carted out.” Pop put on the old country accent: “What is this mishegas? Why is he standing still for it?”

“How humiliating! How am I going to make love to my lady with you old bastards watching me?”

“Oh, we leave you be for that. I was never one for dirty pictures. She’s a pretty lady, your lady. The last one, too, that little Italian girl, she was sweet. You do all right, kid.”

“Shiksas, give me shiksas every time.”

“Mine’s always entertaining, if not always kind.”

I wanted to hear more about married life with Mary McCarthy, but the waiter came and served us our plates from a great height, his eyes averted. The salami was the perfection of salami, just a little dry, wrinkled on the outside. The rye bread was still warm, the mustard Ba-Tampte. I was transported back to his kitchen table on the South Side.

“Food’s pretty good here, don’t you think?”

“Mmmm. I would have thought bread and water, or pig swill.”

“This is the Elysium, and the heroes need their lower chakras taken care of. Down below, it’s not so nice.”

“So there are hot sulfur baths full of naked investment bankers and politicians, like in the New Yorker cartoons? And demons making a trumpet of their ass? Can we go?”

“You want schadenfreude? You should learn to resist it; it’s not good for you.”

I wasn’t so sure about that, but there was no point in persisting. “So if you’re Virgil, you get to go wherever you want. What’s Heaven like?”

“Just as you’d imagine: nice but dull, like a college town. I go to see my mother. Remember Father Kim?”

“Yeah. Nice guy. But dull. And not too bright.”

“He has a poker game on Thursday nights. I used to go, but frankly it’s not much of a challenge. It’s more fun down here with Delmore Schwartz and Isaac Rosenfeld.”

“You guys patch everything up here in the afterlife? They forgive you for the pictures you drew of them in books?”

“Oh sure. They were already dead; they didn’t care. That was all a big joke, really.”

“Mom didn’t think it was so funny.”

“Your mother,” he said, and then thought better of it. “Allan Bloom rides a motorcycle.”

“Has he established the new Bloomusalem?”

“Wears black leather, shaved his head, grew a little flavor-saver on his lower lip. Drives the boys crazy.”

“So a fully actualized Allan Bloom.”

“He wants to be the Ghost Rider when Johnny Storm retires; he’s up your way every weekend, driving fast on twisty roads.”

“If you can’t be Michael Jordan . . .”

“I wanted to be Michael Jordan. Only other person I ever wanted to be.”

“On a page, you could jam. Can I meet my grandfather? Is he really so terrifying? What’s he do when he’s not hanging out with you making fun of me?”

“Devil’s plumber. They call him when the toilets back up. He was always good at making the best of a bad job.”

“People take a shit, here in Hell?”

“They use a lot of it downstairs.”

“So, Pop, to what do I owe the honor of this lunch here on the edge of the Pit? I mean, it’s really great to see you, but I’ve never had a conversation with you when you didn’t have a clear purpose. So what is it?”

“I’ve always tried to help you. No, really, I have. But I didn’t know how. That’s one thing I learned from watching the movie of my life. I’d try to wise you up, and you couldn’t hear it, coming from me.”

“I have made mistakes and later thought, ‘Why didn’t I listen to my old man when he tried to tell me?’ ”

“So you see it, too. Good. It’s my fault, and I’m sorry. I want to tell you how proud I am you’ve made a go of your pottery. It really is beautiful, and look at you in all those catalogs and stores. I see how happy you are when you’re making things.”

“When I was eighteen, you said, ‘At least you’ll always have a pot to piss in,’ and reminded me that Potters’ Field is where they bury you when you die broke.”

“I knew you’d remember. I like a joke too much sometimes, and I feel bad. If you’d gone to art school, you’d have an easy professor’s job. You wouldn’t have to scrape to pay the bills the way you do.”

“Yes, but if I’d gotten it on a silver platter without the key step of defying you, maybe I wouldn’t have wanted it so much.”

“You’re cutting me more slack than I deserve again. Tell me, do I have your attention? Have I persuaded you I have only your best interest at heart?”

“Oh yeah.”

“I’ll give it to you straight: you have unfulfilled ambitions to be a writer, and you are not getting any younger.”

He waited. Slowly I raised my hand, like a basketball player who has given a foul. He held me in his eye.

“I was so pleased when you accepted this assignment, and when you kept avoiding it and finding other things to do, I got a busman’s holiday so I could help you.”

“I certainly am all set for material.”

“All those years covering the statehouse and writing apple pie features, you’ve got muscles, kid. What you need is a deadline. Go home and sit down at your keys and don’t get up until you’re done. Write it while it’s hot. You know how.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And this is the easy one. When you’re done, you’d better write that other thing you’ve been meaning to write.”

“Yes.”

“Don’t yes me!” and suddenly he was my terrifying male parent, Moses down from Sinai discovering the Israelites in idolatry. “We’re in Hell! It cost me a lot of favors to get you down here! Don’t do it for me! Do it for you! Don’t you see?” His voice rose to that pitch and then cracked. “When you’re dead, it’s too late!”

I put my hand on top of his. I have his hands. “Yes, Pop. For me.”

“All right, let’s get out of here. Philip! Put this on my tab.”

Daniel Bellow, the youngest son of the novelist Saul Bellow, was born in Chicago in 1964 and educated in the finest schools. He worked as a newspaper reporter and editor in New York, Massachusetts, and Vermont, and when that petered out, he went back to his original passion, making porcelain pottery. His studio is in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, where he also teaches high school ceramics, writes an occasional column for the Berkshire Eagle, and raises large dogs. He has two children, Stella and Benjamin.