Koba didn't move a muscle.

"Are you deaf or something? Have your ears rotted out?"

"I can't just do it like that," Koba said in a subdued voice.

Yegor burst out into loud laughter.

"Stop," Koba said, in an even quieter voice.

"Well then, get the hell out of here and go into the other room, don't get in the way."

Koba got up and went out the door on the left. Yegor again climbed over to Sashka. The exact same movements with the exact same result. Sashka winced. He couldn't bear this coarseness any longer—he'd been raised differently. He never behaved crudely and couldn't put up with it in others. It was especially vile to hear Yegor address Koba as if he were a girl. Sashka waited a few minutes and then firmly shoved Yegor aside:

"Why do you act so appallingly toward him?"

Yegor hadn't expected a question like that. He raised his head and

looked at Sashka, dumbfounded:

"Oh. Well, I guess I didn't tell you about that. I've known him for a long time, and we have our own sort of relationship. ..."

"Still . . ."

Sashka got up from the couch and buttoned up his pants. He was disgusted. The clock said ten till eight. He still had just a little more than an hour left. It was a good twenty-minute walk from here to the base. "I'm out of here," he decided. It would be better to walk it at a slow pace than to work up a sweat hurrying back. He was just about to open his mouth to say good-bye to Yegor, and then suddenly remembered Koba. He ought to say good-bye to him as well. Sashka opened the door to the other room where his swarthy host had gone. In this small, dark room that looked like a bedroom, a pleasing pink night light glowed. Koba stood next to a large wall-mirror. He was standing in a position where Sashka could see his face in the mirror. Koba was crying. Softly, silently. . . . Upon seeing Sashka, he turned around and quickly wiped his eyes. But Sashka, having seen this, completely forgot that he had come in to say good-bye. He went over to Koba and said:

"Why do you let him talk to you like that?"

"I can't take it any more," Koba said, and another tear rolled out of his eye. "It's been like this for some time already. . . . It'd be okay if it happened only when we were alone, but in front of others. ..."

"But why do you put up with it?"

"It's just my nature . . ."

"Your nature has nothing to do with it. . . . It's disgusting how he acts toward you, and you don't say anything. What is he to you—your brother, a relative, a boyfriend? ..."

"Don't call him my boyfriend. I guess . . . it's our past that keeps us together. ... He seduced me. ... I was still a child then. Do you understand?"

"So that's how it is," Sashka frowned, "well, are you tired of this guy? Or are you going to let him keep on like this?"

"I don't know. . . . It's all so sickening every time it happens. I don't even want to see him any more."

Sashka tilted his head to one side.

"If you want, I'll get rid of him, if he's annoying you."

"How will you get rid of him?"

"Elementary. Properly, calmly."

"Altogether?"

"Well, I'm not sure that's exactly what you want. But he does need to be taught a lesson."

"You think so?"

"I'm sure of it."

"How will you do that?"

"That's up to me. But I need for you to give me the word—remember, you're the master of the house here."

"Gee, I don't know . . ."

"Don't be a wet rag, make a decision. Yes or no."

Koba hesitated a bit, and then finally managed to squeeze out a "Yes."

Sashka went into the living room. Yegor was lazing about, sitting on the couch and leafing through a magazine, evidently not giving a damn about any of this. Sashka's deep and firm voice resounded through the room:

"Yegor, the master of the house requests that you vacate the premises."

Yegor slowly turned his head and stared at Sashka with an expressionless gaze. After a rather long pause, he answered:

"What, has the master's tongue dried up?"

"He just can't come out."

"Has he been struck by paralysis?"

"I don't think so. He just doesn't feel like coming out here."

"So that's how it is. . . . Well, we'll just have to ask him what he wants. Koba! Do you hear?! Come out here, Koba!"

Koba came out into the hallway and stood alongside Sashka. The smile that spread across Yegor's face thoroughly disgusted Sashka. Yegor suddenly seemed to have aged 15 years.

"I've been told that you've requested me to vacate the premises, is this correct?"

"Yes," Koba replied, quite firmly.

"And what have I done to incur his highness's wrath?"

"I can't put up with your boorishness any longer."

"Boorishness? You consider it boorishness that I call a spade a spade? Why don't you say it more directly, that I'm in the way here, that you're falling head over heels for this soldier boy."

"Shut up," Sashka growled.

"Oh yeah, looks like it's big time love here. What the hell. . . . I'll just have to step back for now."

Yegor got up and headed for the door.

"Only you'd best hurry up, my little Georgian," he said, putting on his shoes, "you hardly have any time left. It's already after eight. You know they say that a soldier's love is over with quickly, but maybe it'll be different here. Although . . . maybe you can try giving your uncle a call. I wish you all the best. Take care, soldier!"

Yegor slammed the door so hard that you could hear the neighbors opening their doors and looking out into the stairwell, wondering: "What happened?"

"Jerk," Sashka said.

Koba looked at the door pensively.

"No, he's not a jerk. He's just very lonely and unhappy."

They returned to Koba's room. Sashka understood that Koba was up-

set now, but time was growing short.

"I've got to be going soon, Koba."

"Yes, I understand. And once more I'll be left alone. I don't want that to happen!'

"I'd really like to stay, but I can't— I'm on duty."

Koba looked at Sashka anxiously, pleadingly:

"Tell me truthfully. Promise me that right now you'll answer my question in all honesty. It's very important to me."

"I promise."

"Do you really want to stay, or are you simply saying that so you can leave more quickly? Only tell me the truth, I won't get mad."

"Yes ... I really . . . don't want to leave you."

And suddenly Koba's eyes changed. Sashka noticed this straight away. They became dewy and more gentle. Koba smiled.

"I'm not quite certain, but it looks like I can arrange it so that you don't have to rush back to base. Would you stay if I could?"

"But how?"

"Did you hear Yegor mention my uncle?"

"Yes."

"We've got him to thank for putting the idea into my head. I wouldn't have thought of it myself. The commander of your unit happens to be my uncle."

"Sherikadze?" Sashka asked, asonished.

"Yes. Dato Grigorievich. He's my father's brother."

"And what do you propose?"

"I'll call him up and ask him to allow you to return to the unit in the morning."

"How are you going to explain this to him?"

"Very simple. I'll tell him we've got some people over here . . . some girls . . ."

"He won't allow it."

"I've never asked him for anything like this before. But I don't think he'll refuse me. Will you stay then?"

"Well, then I could. . . . But you won't be able to do it."

"Let me try. It should work out."

Koba once again smiled and picked up the receiver from the phone. He'd already begun to dial the number, but suddenly pressed down the lever and . . . burst into laughter. Sashka was quite surprised.

"What's with you?"

"You're going to laugh, but I don't know your name."

"What, I didn't introduce myself?"

"I'm sure you did, but I must have forgotten."

"Sorry. It's Sashka."

"A wonderful name. Simple and gentle. Okay. Wait a minute—it

doesn't make any sense to call the base now, since he'll already be home." Koba dialed his number:

"Good evening, Grigorievich! Recognize your favorite nephew's voice? . . . How are things? . . . Yeah, same here. . . . Listen, uncle, I have a favor to ask. I've made the acquaintance of one of your soldiers. . . .Well, you know, we've got a nice little party going here. . . . What I really need is for you to be a friend here. Could we somehow arrange it to extend his liberty until morning, since it's almost over. . . . Yes, he's at my place. Well, I'd really like for him to be able to stay. I'm asking you, please. . . . What? His last name? Sashka, what's your last name?"

"Skvortsov," Sashka answered.

"Skvortsov, Aleksandr. . . Okay, got it. Sashka, your company, platoon, and section."

"Second company, first platoon, third section."

"Uncle, second company, first platoon, third section. . . . Okay. I'll wait."

Koba hung up the phone and joyfully turned to Sashka:

"First he'll call the unit, and then back here."

"Do you think it'll work?"

"Now I don't just think it'll work, I'm certain of it."

"He seemed to agree rather quickly."

"Well, you know ... I really shouldn't be telling you this, but, well— you have to promise to keep it between you and me. The fact is that he owes me a bit of a favor. Things haven't been going so well between him and his wife, and so he has this woman friend. My parents often go away for a few days at a time and let him and his woman come over here when I go out. No one besides me knows anything about this. So I ask you, please ..."

"Of course, don't worry about it . . ."

The phone rang, Koba picked up the receiver and in a flash all their problems had been solved.

"Everything's in order," Koba said, "you have to be back on base tomorrow at nine in the morning."

"Great! I can't believe it!"

Sashka felt a flood of fresh energy. Twelve extra hours! Koba was positively glowing.

"So. Today we're going to kick back and take it easy."

He held out his hand to Sashka. Sashka clapped his hand into his.

"Right—we'll kick back and take it easy."

"And have some fun. We'll go through all the champagne."

"We don't have to."

"We must! We live but once. Now off to the tub with you for a bath."

"I've already bathed today."

"In a bathtub?"

"In a bathtub."

"Where was that?"

"At the bathhouse—I rented a room with a tub."

"That's nonsense. I'm going to draw a bath for you that you'll never forget."

Koba went out. Sashka felt like he had just drunk the strongest coffee ever brewed. His fatigue disappeared, he felt easy and carefree. Koba returned a few moments later:

"Everything's ready. Let's go."

When Sashka went into the bathroom, his jaw dropped to the floor. The room was done all in blue and black imported tile; they were beautiful and sparkling clean. There were also two enormous mirrors and shelves brimming with vials containing potions from abroad. But the best part was the fragrance. The bathroom was redolent with the aroma of fresh strawberries. Yes, yes, strawberries! And from out of the bathtub, almost to the very top, there rolled a bright pink foam.

"It's berry-scented bath gel—strawberry—from France," said Koba.

"Well, aren't you something," Sashka said in amazement.

Koba lowered his head:

"If you come by again, it'll smell of currant or apple.

Sashka suddenly wanted to put his hand on Koba's shoulder. He did so, and then said:

"But maybe you won't want me to come by again."

"Don't be a fool," Koba said softly and left.

Sashka grinned and began undressing. What a day he'd had! All kinds of things happening: in all his life he had never experienced so much. Sashka sunk down into the pink foam—it was like fresh strawberry preserves. He'd always dreamed of taking such a bath. . . .

Koba came back and hung up a terry robe. And then he left again. He was so young, yet so self-reliant. ... He should be the one getting into the bath, having a nice soak, and putting on a terry robe, but he was thinking about others. Sashka got out in about twenty minutes. Before the sofa stood the very same little table with wheels, but this time it held a large bowl of steaming borsch, next to which were neatly cut slices of bread, a fresh salad, a bowl of sour cream, and, on another plate, a large piece of meat with fried potatoes.

"Hey you . . . why so much," Sashka said.

"Well, you really haven't had anything to eat today. We can't have that, you need to eat right."

"And you?"

"I had my fill just before you came. Eat up, and I'll go into the kitchen —I need to grind the coffee."

Left alone, Sashka thought: "He went out just so I wouldn't feel awkward eating in front of him." He ate up everything, in the literal sense of the word, wolfing it all down, and then brought the empty dishes to the

kitchen. And wafting from the kitchen was the heavenly scent of coffee. What a kitchen! Everything in it was imported.

"Koba, who are your parents?"

"They're in the trading business."

"And where are they?"

"In Moscow, Petersburg. . . . They're off on a buying trip. They travel a lot. Here, everything's ready. Let's have some coffee, and I also have a pie."

He picked up a large pot of Turkish coffee, a tray with the pie, and went out to the living room. Sashka followed. Koba got out some cups and they settled in on the couch.

"Sasha, how do you know Yegor?"

"We met just today. On a bench, in the public garden."

"Tell me, what he was doing to you here in the living room . . . well, was it very unpleasant for you?"

"You know, it was the first time for me, and. . . . You know, I just can't do it like that, with someone else there."

"Me too. I can't do it when someone's watching."

"That's why I couldn't come."

"So you didn't come?"

"No."

"And before today you had no idea that there could be this kind of intimacy between men?"

"Well of course I thought there might be."

"But you didn't know how it all happened, did you?"

"No."

"Okay, now I'll show you. I keep this video very carefully hidden from my parents."

Koba went out into the bedroom and returned with a videocassette. Only now did Sashka see the Japanese VCR atop the television. Koba loaded the cassette and then poured some champagne, opening yet another bottle. But Sashka couldn't swallow another drop of the heavenly nectar. His eyes were literally glued to the screen. Before Sashka flashed the fairy tale-like beauty of boyish bodies, the most beautiful faces, enormous erect members and music . . . such music. ... It was piercing, captivating, mocking the idiotic government under which this was all forbidden. . . .

There was no end to the caresses and tenderness that flowed like a river from the screen straight at Sashka. He shuddered when fantastic fountains of sperm, inconceivable and unimaginable, shot upward. The champagne flute in Sashka's hand was frozen still, its bubbles, dancing about, long forgotten. Trembling members appeared in every orifice of the human body, moving into any that they possibly could. It seemed unfeasable, physically impossible, and yet it was done with such playful ease and shown in close-up so that deception didn't seem possible. This went on and on. One seg-

ment would end and then another would immediately follow, even more captivating and explicit. And then it was not just a pair of guys having a go at each other, but a threesome ... a foursome ... a fivesome ... a whole crowd. It was a totally new world. Everything was different.

Sashka closed his eyes and hung his head.

"What's wrong?" Koba asked.

But an answer wasn't forthcoming. Sashka simply gathered him up into his ample arms and hugged him tightly.

"Hey, don't suffocate me," Koba whispered and hugged Sashka about the neck.

"I'm sorry, I just can't stand it any more. ..."

"I understand. ... Do what you want to with me, only don't deprive me of life. . . .

Koba kissed Sashka on the lips; Sashka didn't move away. He hugged the boy closer still and groaned lightly. Koba ran his hands along Sashka's chest, and Sashka began quivering all over.

"Sashenka, are you okay?"

"Too okay. I'm going to come."

Koba quickly went down on Sashka's manhood—he barely got there in time. His tool began spurting in such a frenzy that it should have been captured on video. Koba opened his lips and Sashka saw sperm flying through the air, into Koba's mouth. Some of it fell on his chin, his nose, his cheeks. Sashka dropped his hands, now lifeless, to his side.

"You came so fast. . . . You got too heated up watching that video, poor guy," Koba smiled.

He ran off to the bathroom, washed his face and returned. Sashka held out his hand, and Koba pressed to him.

"Koba, turn off the television, that's enough for today."

"I think so too."

The screen went dark and they continued drinking champagne. Sashka looked into Koba's shining eyes—he simply got lost in them:

"How beautiful you are . . ."

"I know. I'm sick of hearing that, though. I don't want to be beautiful."

"Then what do you want to be?"

The spark disappeared from Koba's eyes and once again they became sad.

"Happy . . ."

"Well, that's more complicated."

"You know, that's funny, because for me, it's very simple."

"Really?"

"Yes. I really don't need very much."

"Just one man who wants me. I'm not like Yegor. I'm very domestic, I don't like having all kinds of sexual adventures out there. I don't judge him for it, I'm just different. And that's precisely what annoys him the

The Bench / 311

most—that I'm not like him. Do you understand?'

"I understand."

"So he tries to belittle me. The only thing he really needs is sex. In any way, shape, or form—if in a bed, then in a bed; if in the bushes, then in the bushes; if in an entryway, then in an entryway. But me, what I need most of all is another human being."

"So you mean you're not really interested in sex?"

"No, I like it a lot, only with someone I care about, someone I want to be with."

"Does that person have to be a man?"

"I don't know, maybe I'll fall in love with a woman some day, but for now, that's not happened to me."

"The same with me."

"Really?"

"Absolutely. You know today was the first time ever for me. ..."

"What? . . ."

"I was introduced to sex.'

Koba smiled pensively.

"That means Yegor was your first? Well, I guess that's not so bad. Don't think badly of him, okay? He doesn't have an easy life. You know, tomorrow you'll leave, and we might not see each other again—but he's not going anywhere, regardless of what he's like. Yet I can tell you this much— I won't allow him such liberties any more. You were right about that."

"Why did you say that we might not see each other again?"

"Don't you think that might happen?"

"Well, everything depends on you. You're the master of the house."

"Sashka, I'd really like for us to see each other again. But I was afraid even to bring it up. Do you want to keep seeing each other?"

Sashka was silent a moment and then replied:

"Yes . . ."

"Is that the truth?"

"Yes. Only I don't want Yegor to . . ."

"Well, that's your right."

"Please don't get mad, it's just that it's very difficult for me right now. Only a couple of hours ago, there was nothing like this in my life, and now, everything's different."

"I'll also need time to get used to you. Sanyechka, you should get some sleep. You've had quite a rough day."

"I don't want to sleep."

"Well, what do you want?"

"Just to sit and talk with you. And once more . . ."

"What?"

"To kiss you."

"Well, go ahead and kiss."

It was no longer lust. Gently, softly, tenderly, Sashka kissed Koba on the forehead, the cheeks, the lips. . . . Savoring him like champagne. He got used to Koba, and Koba to him.

"Sashenka, you're so tender and gentle. . . . It's hard to believe that today was your first day."

Sashka smiled and pressed the boy's face to his chest. Koba heard the beating of his young, strong heart. More than anything on earth Koba wanted to freeze this moment, to hear this sound forever. Without a moment's hesitation he would give all of his tenderness, affection, and devotion to Sashka. They kissed and kissed one another. Sashka was once again aroused to the straining point.

' 'Sashenka, you think you could do it again?"

"I could."

Koba got a package of condoms from the table drawer, and lovingly put one on Sashka's tool.

"It's better to get used to rubbers right away. They're a little inconvenient, but they'll save you from all kinds of troubles."

And Koba sat on top of Sashka. His manhood slid in smoothly, and Sashka filled the boy up. It was warm. Tenderness . . . Affection . . . Sensual movements. . . . Then Koba lay down on his back, with Sashka on top. Koba put his legs up over Sashka's shoulders—and Sashka pushed into him, and kissed him, and hugged him. . . .

In the morning they stood for a long time on the threshold, hugging. Koba cried a bit and then raised his head to wipe away the tears:

"God. It's time. I'll wait for you."

Sashka left. He walked past the garden, passing that bench, He grinned —if not for that bench, then none of this would have happened. He remembered Koba's face, his eyes, his voice. God, he couldn't wait to see him again! . . .

I want to be with him! Just to hug him and be still. Not one word need be said.

Sashka had already learned the cherished phone number by heart, and decided to call from the first pay phone! Sashka bolted over to it:

"Hello! Is that you?'

"It's me. What, are you already back on base?"

"No, I haven't made it back there yet."

"Be careful that you aren't late!"

"Koba, I wanted to tell you . . ."

"Tell me."

"I don't know how to say it . . ."

"Just say, how you feel."

"My Kobochka, I . . . I . . . I . . ."

. . . And three simple noble words rang out. . . .

Drawing by Imas Levsky,

"Vitaly Yasinsky" \pseud.] (b. 1946)

A SUNNY DAY AT THE SEASIDE

[Solnechnyi den' na vzmor'e]

Translated by Anthony Vanchu

Vitaly Yasinsky (pseudonym) is a journalist currently working for the "red" press. He lives in Moscow, where his hobbies are, in his words, boys and painting. "A Sunny Day at the Seaside" was published originally in 1992 in the literary supplement to the gay magazine 1/10.

Vagif usually took his student holiday in June. After the trials and tribulations of life in the capital, and his studies at the conservatory, he would feel quite at ease in his quiet seaside hometown.

He had just completed his third year at the conservatory. In the fall, I had joined the army. Each of us understood that we wouldn't see each other for a long time, and thus decided to arrange to spend June together at the seaside.

My friendship with Vagif, at first purely boyish in nature, had become something more. I had never had any friends. I shunned the company of other boys, didn't like getting into fights, and tried to avoid altogether those street encounters on the street where things were resolved with irreconcilable ferocity. In a word, I was shy and closed off, constantly subjected to ridicule and mockery. It was hard for me to take it, but I had neither the character nor strength to defend myself.

And so it happened that Vagif had become my sole friend over the years. It all began one day when, on the way home from school, some boys from another neighborhood were pestering me. A fist fight was in the making, with an undoubtedly dreadful outcome for me. Suddenly there appeared a tall, darkly complected youth. He chased off my attackers, helped me gather up my notebooks, which had been scattered about the grass, and took me over to his house. We gorged ourselves on apricots from his garden; later on, we drank our fill of tea, ate cake, and watched videos until late that night. I felt a sense of ease and well-being that day . . .

Ever since that episode, I would always leave a half-hour early to meet Vagif and we would walk to school together. He was two years older—a difference that seemed like an eternity to me. But Vagif treated me as an equal. And he had my unspoken thanks for that. Suddenly, I had a friend. I tried to keep up with him as best I could. He did gymnastics—and so did I. He took up soccer—and I was there with him. The huge library and piano in his house also attracted me. For the first time I realized that there

A Sunny Day at the Seaside / 381

existed literature other than The Dagger and The Three Musketeers, that there were other books that you could lose yourself in until the morning. I would also listen to the piano as Vagif, my savior and idol, sat and played. He had saved me from loneliness and humiliation.

As it happened, I was at the age where you begin talking about "it." Vagif was the first to tell me about Freud, whom he had already managed to read in full. Our talks aroused strong feelings in me, awakening sweet and sinful desires . . .

That summer we found a quiet and secluded spot on the beach. There was a hanging cliff, a steep shore and strips of wondrous fine sand. But most important of all—there was not a soul around. It was as if we had recaptured our childhood—we were free, young, and strong. We were extraordinarily contented.

Stretching out on the sand, I waited for Vagif to make his way out of the water. I had dozed off. I dreamt that he put his hands, cold and damp from the sea water, on my chest, I shuddered in amazement, trying to free myself from this weight. But it pressed and pressed upon me heavily. And those black eyes, full of lustful languor, pressed upon me as well. His gentle, thin musical fingers had suddenly strengthened, becoming full of desire. And then there was that body, beautiful, powerful, hanging above me.

"Vagif!" I said, gasping for breath, not yet realizing that, unbeknown to my conscious mind or my will, something unexpected was taking place, something that would destroy the past. And I became afraid for myself, for Vagif, for us both.

I involuntarily attempted to hunch up as his masculine hands began to travel along my body in endless waves. His light, tender caresses gave place to a powerful and insistent haste; they were intoxicating, sending a chill throughout my entire body, depriving me of my will.

My wide-open eyes unconsciously gazed into the high blue sky. Not a single cloud there. And here, on the earth, there was an emptiness, ringing and ominous. How could I tear myself away from it? To whom could I call out for help? Where could I run? But I was afraid to stir, because now it was no longer Vagif's hands, but his moist, juicy lips caressing my body. They tenaciously descended lower and lower. I felt their anxious breathing on that place where my impassioned blood had wandered and, with leaden weightiness, had poured itself into my flesh. I instinctively and obediently spread my legs, powerless to resist this invasion any further. Then suddenly Vagif, in one single motion and with inexplicable brutishness, tore my bathing suit from me. Having broken loose to freedom, my member rose up to its full height, effortlessly and shamelessly.

And again, those hands. What were they doing to me?! It was as if they were playing, pressing down on invisible keys. I was entirely in their power. Vagif's thin fingers gently caressed my foreskin. Burning, pulsating currents of blood came alive; my temples reverberated with a dull pounding.

382 / Vitaly Yasinsky

My flesh was filled with some kind of unearthly, unnatural power. Something irreversible and terrifying was about to happen.

But perhaps this wasn't really so irreversible, so tragic. The fear that had taken hold of me was still present, but something else had begun to make its presence felt, something I had never known before. A sweet and delightful languor slowly crept through every pore. My trembling subsided. The cool sand pleasantly tickled my enflamed body. My hands firmly embraced Vagif's pitch-black head, tugging at his hair, caressing his shoulders. And then I felt a hot and gentle touch, the kind of touch that makes the soul seize up and the heart stop beating. His hot, thirsting lips touched my member, this trembling lantern, and took it into its embrace. They enveloped it carefully, unhurriedly, as if fearing they might harm something frail and tender. Giving themselves over to desire and instinct, they began their agonized and anxious movements, raising up from far-off depths my long-slumbering juices.

Everything inside me was tense, like a taut string. It was as if I was all afire—my face, my body, and my member, that triumphant and joyful erection. My torso tore itself from the earth, raising itself higher and higher, urging my flesh on toward something unattainable and captivating.

. . . The earth shuddered beneath me, and the fiery lava that had kept itself hidden somewhere unknown suddenly gushed out with such force that I no longer saw either the blue sky or the bright sun, and could not hear the surf's dull crash. A scorching wave rolled across my body again and again as I lost myself in excruciating exhaustion.

... I opened my eyes slowly. It was still the same sand beneath me, dry and hot. Still the same sky, still the same blinding sun. And the eternal roar of the surf. My world had not come crashing down. But what had happened to me? Had my past life ended? What had just burst into it? I didn't understand. How could I unite these thoughts about tragedy, depravity, and sweet delight flooding over me?

Vagif lay alongside me. Frozen to the spot, I looked at his bronzed legs, spread wide, the black hair lightly winding between him and his flesh, powerful, rearing up, beautiful and proud. I couldn't take my eyes off it, nor could I control myself. What sort of forces, what sort of secrets did it possess? Why did it bewitch and attract me so?

My fingers growing cold, I impatiently embraced his manhood. My hand descended involuntarily. As if tearing away the veil from the face of an unknown beauty, I gazed, enchanted, at the delicate pink head of his quivering member, at the solid furrow that ran from below, at the small darkened funnel at its very end. Through his skin, I could feel how his blood boiled. But then maybe it wasn't really blood, but molten metal? And again my hand, now with a cruel vengeance, went up—and then down. Once more I looked at his naked, defenseless flesh. I wanted to possess its strength, power, and passion. I pressed up against his body as it

A Sunny Day at the Seaside / 383

sprawled out on the sand. I pressed against him—he who had become excited and impassioned, so close to me and so desired by me.

I was feeling good. I felt his broad chest stick to my back, the quickened beating of his heart, his searching, agitated flesh. It burned me, like a heated wedge. It was reckless. It was gentle.

Vagif's hands again caressed my body, now compliant, seeming to lack a will of its own. Effortlessly they pulled my torso up from the ground. All I could see now was a strip of golden sand and a bitter wormwood bush. I felt this impatient and thirsting body above me; it smelled of salt water, sun, and wind. I was afraid to admit to myself that I was anticipating him. It was the first time I had felt this thirst in me, and at that moment, I lived only for it.

Vagif grasped me about the shoulders and pushed himself away; he raised himself up some more so as then to lower himself onto me with the insatiable passion that accompanies only love.

A moan burst forth from inside me. I gasped for breath in passion, joy, and pain. I could no longer restrain the passion raining down upon me—it was something primal. Its incinerating fire spread across my entire body. I could not tell whether it was burning sweat or tears flooding my eyes. I could not even hear my own moaning, hysterical, joyful and grateful.

Did all this really have to come to an end? The world around me had ceased to exist. I didn't belong to it, I just no longer belonged to my self, enslaved by the call of life's passions.

Vagif's ardent hands entwined my body—tenderly, tremulously. Then I grasped him with my thighs, a steel hoop, and began my violent yet pleasure-filled movements with renewed force. I felt every cell of his powerful, strong phallus, its joy and triumph. With every passing moment it became more rapturous and insistent. Vagif surged forward, as if trying to raise me up into the cloudless blue sky. I felt his heated panting, his trembling shiver in the depths of my very heart.

How long would I be able to hold on to this feeling? How was I to know? I was prepared to suffer, prepared to endure all imaginable torments, prepared to refuse all other joys if only what I felt right now would remain.

What would happen next?

My last bit of strength had deserted me. In my fog, I felt convulsions racking Vagif's body and then a surging, burning stream gushed forth into my being.

I accepted this gift. And no one, other than I, knew how bright and clear this day had been, how beautiful this little wormwood bush, how brightly the sun shone in the blue sky.

. . . What a simple thing it is—happiness. In a single instant, a chance encounter on the street is sometimes all it takes to gain it or lose it forever.

"K.E." [pseud.] (b. 1962)

THE PHONE CALL

[Zvonok]

Translated by Anthony Vanchu

"K.E." is the pseudonym/pen name of Ella K. who lives in the city of Oryol south of Moscow and works as a librarian. 'The Phone Call" appeared originally in the gay collection Drugoi (Moscow, 1993).

The gay community in Russia long thought of AIDS as a "foreign" disease, i.e., Russians got it only if they traveled abroad or consorted with foreigners. "The Phone Call" is significant not only because this attitude is totally absent, but also because it deals directly with the effects of the disease on this young man's life from a very personalized point of view.

A phone call woke him up. . . He picked up the receiver.

"Hello. Is Nikolai there?"

"This is Nikolai."

"Ah . . . it's you. Great. Can we get together? Are you busy today?"

"Who is this?"

"It's . . . (there was a short hesitation on the other end) Seryozha. We got together once. . . . You know, we met at that place . . . about a year ago. Don't you remember?"

"No . . . and I don't recognize your voice either. But maybe we. ... So we got together, you say. . . And why haven't you called since then?"

"I'm down here on a business trip. ..."

"Ah ... I see. Where are you right now?"

"I'm at the Salyut Hotel. . . . Maybe we could meet somewhere this evening. ..."

"You know, I'm really not in the mood right now. . . . You woke me up. . . ."

"We can get together this evening. . . . I'll wait for you outside the hotel around six. Okay?"

"Sure ..."

Kolya threw down the receiver rather rudely and once again curled up in bed. But sleep no longer came to him. . . .

He really couldn't place the voice or the name. Yet the whole thing rather fascinated him. In his mind he went through a number of faces, various situations. ... Oh well, did it really matter? . . .

At six o'clock he was outside the hotel.

Standing there was a darkish, rather nice-looking young man.

"Hi. Are you Seryozha?"

"Yes . . ."

Seryozha smiled sweetly.

It seemed that he was a bit embarrassed.

No ... he hadn't seen him before. Or maybe he'd simply forgotten him. . . ?

His memory drew a blank . . . not even a glimmer. . . . But did it really matter, especially now that they'd met up. . . ?

"Well, shall we go up to your room?" Kolya asked.

But it seemed that something was making Seryozha feel embarrassed.

Interesting, was he so embarrassed the last time?

No, he really didn't know who this guy was . . .

He wouldn't forget such a nice-looking man with a trim body. . . . And his eyes ... he could hardly have forgotten those eyes ... so expressive . . . dark, beautiful . . . sparkling . . . and such thick black eyelashes. ... He sort of looked like a Jew . . . like a handsome Jew.

"How long will you be here? ..." Kolya inquired.

"A week. . . . Maybe we could take a bit of a stroll and talk some?" he suggested.

"Sure . . . let's . . . if that's what you'd like. And what . . . what kind of business trip are you here on?"

"I'm an engineer ... a construction engineer."

"Aha. . . . Well, I'm not at all interested in technical things. So you needn't tell me anything more about what it is you do. ..."

In fact nothing really seemed to matter to Kolya. ... He didn't even really need to know this man's name. . . . Moreover ... he wanted things to happen quickly . . . and get the whole dreary process of getting acquainted over with. But Seryozha, it seemed, needed some time to get over his initial shyness. He wasn't behaving like an old acquaintance at all.

Maybe someone else had given him his phone number?

While that was possible, it didn't change anything. It didn't really matter.

Kolya surprised even himself a bit with his own indifference and lack of desire to know anything more about his old-new acquaintance.

What was there to ask about anyway? He'd be gone in a week. Hello and good-bye. And then maybe he'd call again sometime, the next time he was in town. ... Or else he wouldn't call. No one was obliged here.

After a rather short and meaningless stroll, they ended up going not to the hotel room, but to Kolya's apartment. It would be more peaceful there.

Sergei pulled a bottle out of his briefcase . . .

Kolya offered up some scraps out of the refrigerator.

He pulled the shades down, turned on a soft light.

They sat down at the table . . .

"And so, the last time . . . where was it that we got together?" Kolya inquired. "Somehow it's slipped my mind. Besides. . . . Did we see each

other much?"

The other man kept silent, and then admitted what Kolya had suspected all along.

"I'm sorry. . . . But I don't really know you from before. I got your number from . . . Volodya. Do you remember him?"

"Which Volodya are you talking about. . . ?"

"You know, he's got a really solid build, and is a bit taller than I am . . . he's a real fun guy.

"I don't know. Maybe I remember him, maybe I don't. . . . There are lots of real fun guys. ... A solid build, you say ... is he blond?"

"Well, almost ... he has gray hair. ..."

"No, the one I'm thinking of . . . he's quite blond.

They ate and drank disinterestedly.

Kolya looked into Seryozha's eyes. ... He liked his eyes. A nice fellow. . . . but with just a few complexes. . . . He'd have to work on him some.

"If you'd like, I can turn on the TV."

"No, that's okay . . . you don't need to . . ."

The bottle had been drunk up, the snacks eaten—there hadn't been much of them anyway. . .

Somehow Kolya wasn't really in the mood ... to get things going. It was strange ... for some reason ... he just wanted to hug this Seryozha ... lie down in bed with him, and simply lie there next to him. Gently, they slowly caressed one another. ... He didn't even want to get undressed.

But time passed.

He had to do something.

Besides, they still had a lot of time. . . .

Sergei spent the night with him. . . .

He left in the morning. Business to attend to. . . .

Kolya couldn't sleep any more. . . .

He'd been feeling despondent for some time now. . . . Such sadness . . .

He would get aroused, but it didn't last long . . . he'd get aroused, but only physically. Inside—it was as if he didn't even have a soul. . . .

His indifference was profound. How long would it go on like this? His illness gnawed away at him. . . . But his own health didn't matter to him. . . . Tell him tomorrow that you have AIDS . . . surely that wouldn't faze him at all.

There had, however, been a time when he'd had hopes and dreams. . . . When he was looking for someone. ... He used to believe. . . . And cry. ... At one time he had even been on the brink of committing suicide. . . . But then it got to be just like it is with a drug addict or an alcoholic . . . trying to smother his spiritual pain . . . again and again . . . indiscriminately . . . new sex partners all the time . . . and his disease was the result. He got what he needed from them, but did everything mechanically, caring only about the physical part of the encounter. . . . Some of his part-

ners even felt slighted.

And so Seryozha also, it seemed, hadn't liked it too much. . . . He, apparently, had expected something more. . . .

He did everything distractedly, as if he had no control over it. He could, of course, have decided not to have sex. . . .

Sergei, sure enough, seemed like a decent sort of guy, good-hearted. . . . Only what did he really matter to him? What did either of them really matter to one another?

Would he come by again?

He'll come.

And if he doesn't, that doesn't mean anything.

The phone kept ringing insistently. . . .

Kolya didn't pick up.

He just let it ring and ring.

Finally he fell asleep.

Today Seryozha asked him:

"Kolya . . . you're upset about something, aren't you ... it seems to me like something's upset you . . . and you're not talking because for you I'm an outsider, someone who's just passing through. . . . Right? ... is that why you're not talking?"

Kolya grinned and shrugged his shoulders.

"You think I'm upset? No. Everything's fine. I don't have any problems at all."

"You're so reserved. . . . And you do everything as if you really didn't want to be doing it. . . . It's as if you were being forced to do it. . . . Is something wrong?"

"I told you . . . everything's okay."

"I understand. ... I don't have any right to get so personal. But you know . . . I'm so lonely. . . . It seems to me like you might also be . . ."

"Me? . . . What are you implying?"

Sergei didn't answer.

Kolya looked about disinterestedly, scornfully, indifferently.

Kolya didn't refuse the money Sergei offered him the next day.

But he took it indifferently, coldly.

As if it was what was supposed to happen. Whenever someone offered him money, he always took it.

"I don't know what else to offer you. . . ." Sergei said in a strange tone that reflected both caution and awkwardness.

Kolya kept silent.

That afternoon two men came by.

Kolya gave himself up to each of them in turn. And then satisfied both of them together.

He also got really wasted, and didn't even hear them as they left. . . .

He was tired and nothing mattered to him. . . .

And then there was this insistent ringing at his door.

From morning on, again the telephone. . . .

His head was splitting.

Kolya, not really answering the phone, simply swore into the receiver and slammed it down ... he was lucky he didn't break the phone.

Then a short while later the phone began to ring again.

He answered, a bit calmer this time.

It was Seryozha calling; his voice was agitated. "What the hell's going on. . . ?" he asked.

"Nothing's going on. . . . Nothing."

And then he put the receiver back onto the cradle.

It was quiet. . . . Silence. No one was calling anymore.

That evening, at his door. . . .

Why can't you all just disappear. . . .

But it was so persistent.

He went to open it up.

Seryozha . . .

He was frightened and feeling somewhat guilty. . . .

"What's going on? . . ."he asked that question again. "Can I come in?"

"Sure."

"What's going on with you. . . . Why did you freak out like that on the phone? . . ."

"I felt like sleeping this morning. ..."

"And last night I was ringing at your door. . . . Weren't you here? The light was on. Was there someone here with you? ..."

"I was asleep, understand. . . . Asleep! I didn't hear anything."

"Oh all right, never mind. ..."

It was kind of funny to Kolya that Sergei took this all to heart. He was in a hurry, after all—he'd be leaving soon. And of course he'd given him money. And here he is, messing around with other guys. It was, to be sure, insulting. . . . But was he to blame that the guys had come around?

They lay next to one another, naked . . .

"Do you like me?" Kolya asked calmly. . . .

Kolya was asking him . . . and looking at him with interest, but somehow as if from afar. . .

Sergei turned his head. He looked into his eyes. . . . And then averted his gaze and quietly, with tenderness and care, looked at Kolya's shoulder, his hand ... his fingers slowly slid down his body.

He kept silent.

"Will you see me off at the train station?" Sergei asked, already dressed, his briefcase in hand.

Kolya looked at him, propping his head up while lying in bed, curled up under the covers.

Then he slid back onto the pillow, smiled and shook his head, closing his eyes ... as if luxuriating.

Kolya heard footsteps.

Sergei was leaving. He was leaving, not even having said good-bye.

The door slammed.

Kolya continued to lie in bed. But now he was just staring at the ceiling.

His gaze was frozen. . . .

Then he got up and began pacing the room. . . .

There was a farewell souvenir on the table ... a little gray downy swan ... a children's toy. . . . But so touching.

Kolya stroked it cautiously. ... He liked it. . . . It was soft . . . pleasant. . . .

Then he went into the kitchen to drink some water. ... He looked out the window. . . .

It was a gloomy day . . . soon his life would end . . . altogether.

Kolya slowly wandered back to his room, opened his dresser door and looked at himself in the mirror. . . .

He was still naked. . . .

Again he lay down on the bed.

And shuddered. . . .

In the stairwell he heard some footsteps ... a shuffle. . . . Was someone coming to see him again?

What was he so afraid of? . . .

The noise passed by . . . passed by. . . . He didn't get a lot of guys coming by to see him. . . . The neighbors would take note of something like that. . . . Visitors. . . .

He closed his eyes. . . .

No, he didn't want to sleep at all. . . .

Like Seryozha had just said to him. . . . "You're so young . . . handsome . . . why are you so detached from everything ... so cold . . . can it be that you never loved anyone? . . . You're indifferent to everyone. Why do you give yourself up as if it were an act of kindness, as if you had no need of it, and were doing it only for the other person . . . can you really be so totally apathetic . . . with everyone? Completely indifferent?" And he then, maybe wanting to defy his depravity, or maybe in fact it was how he really felt, answered: "Yes. I am indifferent. I need only a pr*** . . . who it belongs to . . . that doesn't matter. . . ." "So you'll give it to anyone, huh? . . . Whoever wants it?" Sergei had asked, it seemed, even with a certain sort of horror. "Yes . . . I'm a humanist," Kolya joked.

What did he want from him, why did this guy on a business trip keep asking him about these things?

Then he left, without even saying good-bye.

Once again the phone rang.

Who needed him now?

"Yes . . ."

". . . it's Seryozha. Kolya . . . listen to me. Come to the train station, okay? There's still time . . . it's almost an hour before my train. Come down. . . ."

"Why?"

"You know which train it is. I'm in car number fifteen. I'll be waiting for you. . . . I'll tell you why ... if you come . . . otherwise it wouldn't make any sense. . . . Will you come? ..."

"Why?"

On the other end of the line he heard the receiver slam down.

But in point of fact, why? . . .

Kolya slowly put down the phone and once again lay on his bed.

He wasn't going anywhere. . . .

Anyhow, he knew what the other guy would say. . . .

Kolya smiled, almost mockingly. . . .

He turned his head to the side and lay there ever so quietly. . . .

How much time passed by like this?

Even if he left for the train station right now . . . he'd still be late.

Besides, he knew what that guy would say to him.

Kolya slowly got up from his bed.

Well, what did he want to say to him? . . . What? . . .

Wasn't it all the same anyhow? . . .

Kolya got up. Slowly, lazily, he moved about his room as if still half-asleep. . . .

He stumbled into the chair he'd left his clothes on. . . .

A shirt slid to the floor. . . .

If he got dressed right away . . . then maybe he could still make it in time . . . he'd get there . . . run there. . . . But no. ... It wasn't worth it. . . . It wasn't worth doing.

Again he moved slowly about his room.

Again he sat down on his bed, sort of hunching over, his head bent down. . . .

Now he surely couldn't make it on time. . . .

Even if he had wanted to.

Minutes, seconds slipped by, flying by without pity, quickly becoming history. They disappeared forever. There remained only the present. ... It swallowed itself up and became eternity. . . .

Again some sort of sudden ringing brought him back from his distanced and torpid state.

Again Kolya, for the second time that evening, shuddered and, surprising himself, picked up the receiver right away.

"Kolyukha, is that you? Hi! It's Slavik. Have you missed me?"

A malicious smile spread across his mug, that much was certain. He knew there'd be no refusing, he knew . . .

Kolya silently threw down the receiver. He had expected a completely different voice.

He looked at the clock.

One minute before his train left! . . .

He wouldn't be able to get there in time. ... Of course now there was

no way he could have made it there! . . . And he wasn't even dressed. . . . But if the train was late, then wouldn't he be leaving later? . . .

No ... No ... No!

No!!!

Now he clearly understood ... it was too late.

He slowly lay down on his bed, wrapping himself up in the sheet . . . and calmed down . . . curling up into a ball, burying his face in the pillow.

No!!!

... He shouldn't have let him go.

This Seryozha ... it must have been his destiny. He would never find a gentler, kinder, more sensitive man. . . . How that man had wanted to know who he was ... to know the truth ... his soul ... to become his friend.

Couldn't it have happened? . . .

Why had he been so cold, indifferent, so cynical? . . .

Oh God . . .

They simply hadn't had the time ... to get to know one another better. That's not true . . . there had been time. Had it really been so short?

He almost didn't hear the bell. . . .

But someone was now ringing again, insistently. . . .

He wouldn't go see who it was, he didn't need anyone. . . .

And then there was a ringing at his door.

Let them ring all they like.

Let them break the door down, he wasn't going to open up.

Let them . . .

But why were they ringing with such insistence? . . .

Who could it be?

The scum . . . Bastard . . .

It was that Slavka ... so what ... to hell with him. . . .

But maybe Seryozha hadn't left after all?

Why had such a strange thought entered his head?

Probably because he wanted him so much right now . . .

And Kolya got up slowly and went to the door.

Blood pounded to his temples. . . .

Cautiously he opened the door.

No, behind the door it wasn't Seryozha at all. . . .

It was Slavka. And a couple of other guys who'd been drinking.

He stepped back slowly.

His next-door neighbors were having a drunken row. . . . What a racket and din . . . singing. . . .

The three of them entered the apartment. The door closed.

He kept backing up, into the depths of his apartment ... a shudder came over him ... he broke out in a cold sweat . . . everything went dark. . . .

I beg you . . . Oh my God . . . help me! ... I beg you . . . Dear Lord.

J

m

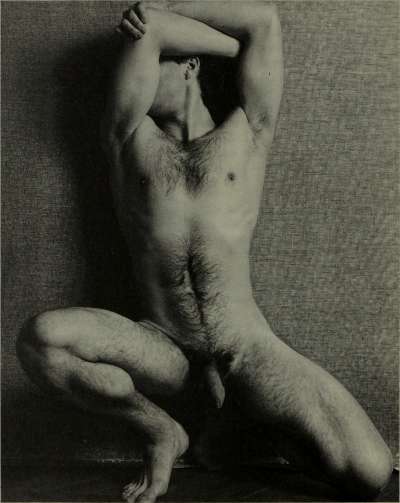

Photo by Alexei Sedov.

Yaroslav Mogutin (b. 1974)

THE DEATH OF MISHA BEAUTIFUL

[Smerf Mishi B'iutifula, 1996]

Translated by Vitaly Chernetsky

Yaroslav Mogutin (b. 1974) is probably the best known "out" gay literary figure among Russians today. Since 1991 he has been publishing essays and articles on literary and cultural topics in both the mainstream and the alternative Russian media. Mogutin became the first to confidently speak out in Russia from the point of view of a gay man comfortable with his sexual identity. His poetry has appeared in a number of literary journals, and he has also edited several editions of gay literary classics, notably the collected works of Yevgeny Kharitonov and the Russian translations of Giovanni's Room and Naked Lunch. Mogutin's articles, frequently dealing with controversial issues, earned him the honor of being named cultural critic of the year by Nezavisimaya gazeta in 1994, but they also provoked the displeasure of the Russian authorities and increased harassment by them. In 1995 the threat of persecution forced him to leave Moscow for New York, where he applied for political asylum.

Some friends from Moscow who recently passed through New York relayed the shocking news: Misha Beautiful was killed in prison. The story of his brief life could provide excellent material for a book or a movie. His name did not appear in the society chronicles. Actually, nobody even knew either his real name or his age. People were saying at the time of his death he was nineteen. His death wasn't reported in newspaper obituaries, and it is unlikely that anyone except me would write about him.

Not a single drug or rave-related party could take place without Beautiful. Almost everybody knew him. He was one of those exotic nocturnal creatures, those girl-boy club kids who keep it all going in any one of the world's capitals.

We met at Michael Jackson's concert at the Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow, where I was taken by Vladik Monroe who had free tickets (of course I wouldn't have gone to watch this American gnome with my own money). There was an incredible number of cops there, one of whom displayed rather aggressive interest in me, catching me taking a leak in an inappropriate place. Only my journalist ID saved me from his insistent pestering. At the stadium entrance several lines of cops thoroughly searched and felt everyone. This got Monroe very excited and he went back and forth about three times to prolong the pleasure.

394 / Yaroslav Mogutin

The concert was a flop, the weather was nasty, the rain was pouring, and people were standing up to their ankles in water. Misha came up to us and asked for a smoke. It turned out that previously, back in St. Petersburg, he tried to "get" Monroe for a long time and claimed to be in love with him. Don't know what ever happened between those two, but Vladik told me he was now trying to avoid Misha.

Monroe and his retinue left, and I remained standing in the rain with Misha, who was high and seemed to have some difficulty understanding what was going on around him. Later I never saw him completely sober, looking normal; his pupils were always dilated. Misha was a clear case of a teenager who grew too quickly—tall, dystrophically thin, boyishly awkward, with long arms and legs and with shoulders and chest that had not shaped up yet. He truly was beautiful with the innocent childish expression of his face, wide open eyes and long lashes, with a short haircut, always in a baseball cap turned backwards and with rings in both ears, nose and one eyebrow (piercings always excited me!).

He slightly stuttered and slurred when he spoke, and his vocabulary was full of slang and Russianized English words. Later he became for me a walking dictionary of this simultaneously entertaining and somewhat stupid language that served as a password of sorts for the "in" crowd. His head was an utter mess, he jumped from one thought to another, and his speech frequently resembled a Joycean stream of consciousness. I liked his stories and fantasies; to me they looked like good material for an absurdist play yet to be written.

After the concert he had to go back to St. Petersburg. In a kiosk by the metro station I bought a bottle of vodka which we drank right there, chasing it down with some nasty franks. He got drunk in an instant and was overflowing with tenderness toward me. He wrapped himself around me, grabbed and kissed my hands, felt my cock, whispering excitedly, "Wow! So big!" We embraced, kissed and rubbed against each other like lusty wild animals, cold and wet from the rain. Old drunkards standing nearby watched us with both hate and surprise.

Catching the last metro train, we found ourselves in an empty car and lay down on a bench, still kissing and embracing. He unbuttoned my fly, got his hand inside, and started squeezing and caressing my cock. At the moment when he was about to take it in his mouth, two Georgian men walked into the car. I understood by their reaction that they could have easily killed us right there if we did not manage to jump out of the car an instant before the doors closed. When I saw him off at the train station, we parted as if we had been lovers for a long time: we only had known each other for about three hours!

He called me all the time, often leaving some ten messages a day in his bird language on the answering machine. The messages were about him loving me very much, him thinking about me all the time, wanting to see me,

The Death of Misha Beautiful / .395

feeling bad without me, deciding to kill himself, overeating magic mushrooms and thinking he was about to die, having some girl and imagining I was doing to him what he was doing to her, and so on. At the time I was already a well-known journalist and regularly received calls and letters from the fans that I suddenly acquired. But Misha differed from them in that he hadn't the slightest idea about the things I did or the origin of my fame and wasn't at all interested in that. In any case, I am certain that he never read a single line of what I had written (if he knew at all how to read). However, occasionally he became the inspiration for some of my writing. In the pornographic poem "Seize It!" dedicated to him there are the following lines:

and that boy in a baseball cap with a shelf that sticks out takes and swallows like a god nobody else could do it like him

The parents of Misha Beautiful are well-known and respected in St. Petersburg. I believe his father is the director of some large department store. And, as it often happened in well-off Soviet families, he grew up "difficult," a "problem child." He told me about doing fartsovka (trading with foreign tourists) next to the "Intourist" hotel. The queers who "picked up" foreigners also hung out there. Misha and his trader friends periodically bashed the queers: beat them up and took away money, watches, jewelry and such. Misha did not consider himself queer.

From his other stories I found out that as a child he fell down a staircase and suffered a severe concussion. Apparently this was the reason why his mind was clearly slow. I was only older than him by some two years, but it seemed to me that a veritable age gap divided us, turning our communication (when his mouth wasn't busy with something else) into some inarticulate babbling. He had the intellect of a five-year-old child, with only two passions: drugs and parties. And, of course, beautiful and expensive clothes. He didn't like to work and didn't know how, and when he ran out of his parents' money he stole or begged his friends for money; many of them used Misha as a prostitute in return. If one were to try to count his lovers or just fleeting partners, the result would appear as a rather long list of names, with many celebrities among them. For Misha sex was the only way to earn income, and he had all he needed to become a successful hustler.

Misha did not have a strong will or character, which is why, like some "son of the regiment,"* he had a need for elder comrades. Having found

* A term used to describe orphans found and taken care of by Soviet army regiments during World War II, an important element of Soviet cultural mythology.

396 / Yaroslav Mogutin

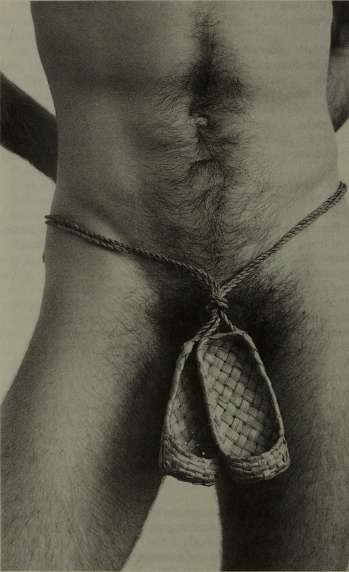

himself in the coterie of Timur Novikov, Beautiful became a student at his New Academy of Fine Arts. Timur himself had admitted that one of the main criteria he used for selecting students was attractive appearance—a quality thanks to which Misha, like other beautiful creatures, successfully passed the "face control" and became a pupil at this unique educational institution above which hovered the sinful spirit of Baron von Gloeden and Oscar Wilde. Timur's boys served as naked models for each other, had their pictures taken in ancient garb and poses on roofs or at the Academy itself, located in a large communal apartment, one of the walls of which was covered from floor to ceiling by satin of the symbolic sky blue color.

Timur (whom Misha referred to respectfully as Timur Petrovich) was for him for a while a true idol and figure of authority. But even he, despite his definite organizer's talent and his skill in (let's say) "working with the young," managed to divert Misha from the lifestyle he had been leading only for a short while. Fine Arts interested him far less than drugs and parties. Timur Petrovich sincerely tried to bring him to reason and to take him back to the realm of beauty, but his efforts were in vain. . . .

Misha gave me a big surprise by showing up in Moscow on one of the days of the October 1993 putsch, during the state of emergency. He must have been the only person in the world who knew nothing about it. He had no papers with him. He called me from the train station. He had tons of acquaintances in Moscow, but he called me and no one else since, according to him, he came down to see me. And I felt some responsibility for him. Dropping everything, I grabbed a pack of my journalist IDs and went to meet (or, rather, save) him.

The previous night Monroe had been arrested when he was wandering around Moscow, having his pictures taken for his magazine Ya and making indecent poses in front of the tanks. Vladik and a friend of his had to spend a night in pre-trial detention. This probably was the best possible scenario of what could have happened to Misha. I did not know what to do with him or where to take him. I could not even bring him home, since my pathologically jealous and hysterical lover was there, and he could have easily killed me, Misha, himself, or all three of us.

Having found out that something scary and incomprehensible was happening in Moscow, Misha went into raptures and begged me to take him to the White House. The most surprising thing was that he succeeded in that. The invisible evil snipers followed us desirously with their eyepieces, stray bullets whizzed by, the level of adrenalin in our blood exceeded all the Health Ministry's norms, people wandered in the streets, ogling and dumbfounded; all of this served as an arousing backdrop. Like homeless teenagers forced to engage in public sex, we found ourselves in alleys and doorways, and Misha used every opportunity to directly communicate with the object of his desire. Several times we were caught in the middle of it, but in that extreme situation our pranks did not cause particular reactions

in anyone. (Queers on barricades!) So this was my baptism by fire. I will always remember that sharp feeling of sex in the midst of war, and I understand very well why shooting, war, occupation have been depicted in such desirous ways in Genet, Liliana Cavani, Tom of Finland and many others.

I am writing about Misha in such detail, trying to recall all that I know and remember about him precisely because he is no longer in this world, and I am getting excited under the pressure of some cruel and dark necrophiliac fantasies. I know this is blasphemy, that de mortuis aut bene, aut nihil, but I am describing him the way he was, portraying him as a tender exotic plantlife, a delicate blossom, unadapted and unprepared for life. He was doomed. He had it imprinted on him, and it was difficult not to notice that. I knew that, sensed that, and repeatedly tried to do something to influence his fate. But I had not fallen for him that badly. I had a life of my own into which he intruded from time to time; we met periodically and made love, he was always somewhere nearby, and it seemed things would stay like this forever. As I was moving across Moscow, changing addresses and lovers, Misha somehow managed to find my phone numbers and called me, giving me more material for the absurdist play I had conceived and running into my jealous boyfriends from time to time.

On April 12, 1994, the day of my twentieth birthday and of the legendary attempt to register the first same-sex marriage in Russia I undertook with my American friend Robert, Misha's half-ghostly figure suddenly appeared in the crowd of reporters armed with erect cameras and microphones. As is well known, our marriage wasn't registered, but we managed to make enough noise for all the world to hear, and we bravely withstood the marathon of endless filmings and interviews that followed. As in the case of the putsch, Misha was probably the only person unaware of this historic event. He fluttered his eyes and wrinkled his forehead in surprise, failing to understand who was marrying whom and why there was such commotion.

I had neither the opportunity nor the desire to explain things to him and deal with him at that moment, and I decided to give Misha away to my friend Fedya P., the son of a famous woman writer. Fedya was a cute young man and a novice journalist with good brains and a kind heart; prior to this the two of us "did it" somewhat awkwardly a couple of times (on his initiative, in spite of Fedya usually acting straight and repeatedly trying to lecture to me about my "sinful" way of life). I knew he wouldn't mind "doing it" with someone else. Misha was an ideal character for that, and he obediently went with Fedya as he was told.

After the noisy party at Robert's studio Fedya took Misha to the apartment he was renting separately from his parents. Having slept with him that night, Fedya departed either for work or for college, leaving Beautiful at his place and making the noble jesture of leaving him the only key. He

398 / Yaroslav Mogutin

promised to get Misha a journalist ID so that he could attend any cultural event without problems. More than a month passed before the trusting Fedya managed to catch Misha and get the key back from him. He had to pay for the apartment he couldn't even get in, while Misha turned it into a drug den, did not answer calls and hid from the naive Fedya. But an even greater surprise was still awaiting Fedya: his landlord demanded that he pay for Misha's long distance and international calls (he must have been leaving numerous messages on his lovers' answering machines). "But I tried to help him, to drag him out of this swamp!" Fedya later complained to me, frustrated in his best feelings.

Several times I ran into Misha in various clubs, and by then he was already so high he could hardly recognize me. His speech consisted of half-senseless interjections a la futurist zaum. Later Misha disappeared somewhere, and different stories about him reached me from time to time: he had hung out with some Scandinavian DJs who drugged and "gang-banged" him; he had to move completely to Moscow since in St. Petersburg people from whom he "borrowed" various valuable things were trying to hunt him down; that people were beginning to look for him in Moscow for the same reasons as well. Once an acquaintance of mine called me to ask where one could find Misha to ask him to return the video camera that had disappeared after his visit. Misha had gone too far: for the majority of people he stopped being "beautiful," and clouds were beginning to gather above his head.

Our last meeting took place when he called and found me in a kind of sentimental and lyrical mood. I missed him and his silly stories. We walked around town and he entertained me with stories about his parents frying some mushrooms and him adding some of his own, and then his parents started seeing things, and his grandma had the most serious hallucinations. "I don't understand what's happening to me!" exclaimed grandma. "I feel like a completely different person!" Another story, completely unrealistic, was about some rich mistress Misha had who liked anal sex and Misha satisfying her. Misha himself confessed he grew to like anal sex as well. He said he'd been invited to go work as a model either in Italy or Spain, and that he would go there "as soon as he's ready."

Having bought a couple of bottles of champagne, we dropped in at the studio of my friend Katya Leonovich, on the Garden Ring. She was having a business meeting with a couple of obscure journalists who nearly fainted at hearing my name. Having gotten drunk on champagne, we started behaving in a rather unrestrained manner. Just like the first time, Misha wrapped himself around me and our fit of tenderness finished in the bathroom where I resolutely brought him down on his knees and pushed my cock into his mouth. He diligently and skillfully sucked and licked it, stopping from time to time, looking puppy-like into my eyes, saying pitifully and devotedly, "Please don't abandon me! I beg you! I want to be

The Death ofMisha Beautiful / 399

with you!" At that moment I wanted only one thing—to come—and could easily promise anything. When it was all over, we came out of the bathroom to meet the frightened gaze of the obscure journalists. Then Misha undressed to show his tattoos, and Katya had him try on one of the outfits from the collection she was working on. Being at the center of attention, Misha was shy and at his best. One could do anything one wanted with him, like with a doll or a mannequin—he was so obedient-malleable-passive.

On the eve of our departure (or, rather, escape: I had to flee from another case that was brought against me) from Russia, literally a few hours before our plane, when Robert and I were hurriedly trying to pack at least something, Monroe burst into our place with his friend Ivan Tsare-vich and the conceptualist artist Sergei Anufriev. Monroe and Ivan were then renting an apartment on the Arbat, a two minute walk from us, and whenever they completely ran out of money they would come to our place to eat. We thus had to put off the packing until the very last moment and feed the hungry artists. It was then, at our last supper, that I learned from Vladik that Misha Beautiful had gone to jail for theft and drugs. We made a bad joke about "Misha now going to feel good and having an intense sex life in prison'' and so on. But since I had a good chance of finding myself behind bars as well, I understood perfectly well the seriousness of what had happened.

For a homosexual prone to sadomasochist fantasies, prison sometimes appears as an enticing sexual paradise, a place where the most daring dreams and fantasies come true. Such beliefs are usually taken from the porn films of Jean-Daniel Cadinot, the books of Genet, or even domestic prison folklore. One can fantasize about this for a long time, and these fantasies can be tempting and beautiful. But I have seriously investigated the topic of homosexuality in Soviet prisons and detention camps, and I know what happens there up to this day to those like myself and especially like Misha Beautiful. It doesn't matter that he didn't consider himself queer.

The story of his life and death could easily be reworked into a moralizing oration: look what drugs, homosexuality, parties, idleness and loose nightlife do to a person! He started out with fartsovka and mushrooms, and finished in prison, among the criminals! But one can also present it in a completely different way: it's a pity that there did not appear a Michael Jackson who could have saved him and turned his life into One Big Disneyland. It's a pity that neither Monroe nor Timur Petrovich, nor me nor Fedya became his Michael Jackson.

Poem: THE ARMY ELEGY

[Armelskaia elesiia, 1994]

Translated by Vitaly Chernetsky

To the soldier Seryozha, whom I discharged from his post at four o'clock in the morning, having introduced myself as the son of Russia's Defense Minister.

The scent of a soldier's cock is beyond comparison Which is well known in New York Berlin and Nice There they know all about tenderness When taking a sniff of the crotch

Terrains of alien pillows Stains of alien sheets The disparity of guns' caliber Grows in viciousness and length

I did not have anyone except the Army Rosy-cheeked soldiers fall out of windows Like Kharms's old women* When they try to gaze at the sky Their resilient bodies are dragged away (And there's something farcical in it)

The intoxicating smell of the barracks and dirty feet

The creaking tenderness of several pairs of entangled combat boots

(What to do—I couldn't do otherwise any more)

Foreign queers are aroused by Russian soldiers

Russian soldiers are not afraid of foreign queers

They bravely gaze at the sky

Many of them did not have anyone except the Army

They fall out of windows

And their able young bodies fall into foreigners' hands

They are dragged across the border

usually to Paris Berlin New York or Nice

Smuggled by a firmly united lusty gang

Getting through customs with difficulty

(The creaking and scent alone could drive one crazy

Were it not for the tenderness

That squeezed the crotch in the final gasps

Of disparate guns alien sheets and pillows)

*An allusion to "Old Women," by Russian absurdist writer Daniil Kharms (1905-1942).

Dimitri Bushuev (b. 1969)

POEM: "The night will burst with hail, and the rain"

Translated by Vitaly Chernetsky

Dimitri Bushuev (b. 1969) studied at Ivanovo University, north of Moscow and the Gorky Literary Institute in Moscow. His poems have appeared in various literary journals in Russia, and he won the Yunost literary award for best poem of the year. His book collection of poems Usad'ba (Country Estate) was published in Yaroslavl in 1991. Of recent years he has been living in England and working as a Sports Commentator (Russian speaker) for the Satellite Telesport Ltd., London, while continuing his writing. The prose printed here is from a long, unpublished novel, Echoes of Harlequin.

The night will burst with hail, and the rain Will pour down, like sayings from the Cabbalah, While Autumn carries slender glasses Filled with hot amber.

A different, brightly colored wine The harlequins once brought me, With stars and rubies all inside it, And ships sinking down to the bottom.

Like under a chimera's wing I sit alone next to an old book Where three pages of wild strawberries Are blooming under a bronze cross.

I am gay, and hence I know the magic

Inside the sealed sea bottles and under the roots—

But you have called it all

Boyish pranks and tomfoolery.

I might be going down to hell Through the dark windowless cabins And there I kiss Demon himself on the lips, Dictating a tale amid falling leaves.

Photo by Alexei Sedov.

Dimitri Bushuev (b. 1969)

ECHOES OF HARLEQUIN

[Na kogo pokhozh Arlekin]

Selections from the unpublished novel

Translated by Vitaly Chernetsky

1 sensed your field of energy, the currents of warmth, the peculiar vibration of the air, mixed with your familiar scent; my chakras exuded golden balls, the cod liver oil of constellations floating around me. The root of my life hardened painfully, I could barely restrain myself from hugging you and whispering in your hot little ear, "I love you, Dennis." I was screaming in my thoughts, screaming for all the Universe to hear; the blood pulsated in my temples; I wanted to loosen my tie, raise my head and whistle like a nightingale! I sensed fantastic blips and explosions of energy—it seemed to me that I could overturn a train, tear a wing off a plane, saddle a rhinoceros or even screw a crocodile—for you. And how much verse, mountains of verse of the highest standard I composed, burning in my flame! You won't be able to read them. . . . And in the meantime, hold your pants better and button up your fly so that your sparrow doesn't fly out. And has it even grown its feathers yet, this little bird? And generally, keep your ass close to the wall, you little squirrel. . . . You lick your dry lips, the poisonous tip of your tongue glides over the pearls of the two wide front teeth. Lord, Lord, what do I do with my beastly tenderness, the burning bush of passion, what do I do with my beauty, my youth and strength? Look how much champagne sparkles in my blood, how my flute sings in the warm nights of the East, how eternity, immortality, peacefully spends the night inside me—only the swallow of black eyebrows flies over the sea of life. When Judgment Day comes I shall look for Dennis in the crowd— Lord, put a red band on his forehead so that I can find him faster.

After class you came up to me to double check the numbers of the homework exercises, but why then, you sly little thing, were you casting glances out the window where you could see my mustang in the bike lot? Triumphantly I opened the door of the closet where the two brand new helmets were sparkling: one orange, the other purple, with a fantastic butterfly upon it! The fragile boy in this huge helmet looked like an extraterrestrial from the constellation of Aquarius—where, but where is the highway knight in black leather carrying him, have you seen by any chance where they went? Police! Firemen! Witnesses! The first lanterns lit up on the embankment, lights floated down the river, a fisherman's figure grew still on top of a bridge. I stopped and asked where we should go now. With unexpected abruptness, you answered, seriously. "To the park!" At that mo-

ment you seemed strangely adult and sullen, like a pigeon with its feathers ruffled up.