WORK AND LIBERTY

CLINK … THUD … CLINK …

This was the annoying series of sounds that woke Joe Small almost every morning at Port Chicago. He’d open his eyes and check the clock—just 4:30.

He’d try to get a little more sleep, but the clinking and thudding would continue. Small didn’t have to look out the window to know the cause. The guy they called T. J. was out there in the dark, pitching horseshoes in bare feet and boxers, his sneakers tied together and hung over his neck.

T. J. did this every morning, week after week. Small figured T. J. was angling for a Section Eight—a discharge given to men mentally unfit for service. Anything to get out of Port Chicago.

Whether Small got back to sleep or not, he was usually the next member of Division Four to get out of bed. He’d always been an early riser, and the other men quickly began counting on him to get them up and on their way to chow.

“All right, buddy,” Small would say, moving from bunk to bunk, shaking heavy sleepers. “Let’s go, buddy, get up.”

* * *

He’d been like that from a young age.

“My father didn’t believe in me depending on help,” Small would later explain. “He taught us to be independent.”

Growing up on his family’s 80-acre farm in New Jersey, Joe handled jobs in the fields and around the house. “For instance I had the chore of bringing in the night pail every night,” he said. With no indoor plumbing, the Smalls used an outhouse during the day—and at night, the pail. “And if I went to bed without getting that night pail in, if it was needed at any time of night, I went out and got it.” Didn’t matter what time it was, or what the weather was like. “I’ve gotten out of bed at 3:00 in the morning,” he said, “in two foot of snow.”

One afternoon, when Small was fourteen, he was hanging out at a roadside truck stop near his home, watching the big rigs come and go. A driver stepped out of the restaurant and saw the skinny teenager staring up at his truck, piled high with long logs. He thought he’d have some fun with the kid.

“You think you can move that?” the driver teased.

“Sure, I can,” Small snapped back. “I can drive anything on wheels.”

A slight exaggeration—he’d driven a tractor on his family’s farm, but that’s about it.

The driver smiled and pointed up to the cab. “The key’s in it. Go ahead.”

Small climbed in and took a quick look around. He started the engine, grabbed the shift stick, and wrestled the truck into first gear. Then, gently, he lowered his foot onto the gas pedal.

The driver looked up, stunned to see his rig begin rolling through the parking lot. He hollered for Small to stop.

Small’s foot slammed on the brake. The jolt of the sudden stop sent one of the logs sliding forward; it smashed through the back window, sped past Small’s head, crashed through the front windshield, and came to a stop sticking out from the front of the truck.

There was a short silence.

And then the driver erupted with a burst of curses, roaring so furiously he literally started hopping up and down. Small opened the cab door, jumped to the ground, and took off down the road.

Joe’s father died a year later. The family scraped by, growing their own food, sometimes selling extra tomatoes and lettuce. But the Smalls needed income, and Joe stepped up.

In a local newspaper he saw that a furniture company was looking for truck drivers. He was just fifteen. He didn’t have a driver’s license, and didn’t exactly know how to drive a truck. None of that stopped him. He walked into the furniture company’s office and asked for the job.

“You got a license?”

“Yeah,” Small said, tapping his hip pocket.

“All right, all right,” said the manager, “as long as you got it.”

Joe drove for the company for a year and finally got his driver’s license when he turned sixteen. All the while, he tried to keep up with school. The schoolwork was no problem, but there was an irritating kid in his class, a white kid who thought it was funny to call black kids like Small “Smokey”—and then duck behind his 200-pound cousin.

Small was thin, about five foot seven, but never one to back down. He promised his tormentor he’d catch him one day when the big cousin wasn’t around. He kept the promise. “I put a good whipping on him,” Small recalled. “They gave me an alternative: either leave school or be sent to a reform school.”

That was the end of Joe Small’s formal education.

Small was twenty-two years old when he got to Port Chicago, a few years older than most of the men in his division. He had a bit more life experience than the other men, and the confidence that came with it.

“I demanded, I guess you could use that phrase, I demanded respect,” Small later said, explaining how he came to be seen as the unofficial leader of his division. “I mean, I would tell a man, ‘Shut up. You talk too much.’ Look him straight in the eye, and that was it, and he’d get the opinion I meant what I said, and if he didn’t shut up the consequences would be disastrous. And through that attitude I gained the respect of the men.”

* * *

Small and the men had to be dressed and ready for work by 6:45 a.m., when their lieutenant’s voice came blasting out of the speakers in the barracks: “Now hear this, now hear this! Division Four, Barracks B, fall out, fall out!”

From that moment, the men had exactly two minutes to line up in the street outside the barracks. As they were forming ranks, elbowing each other into place, Lieutenant Ernest Delucchi walked up to inspect his division. A schoolteacher in civilian life, Delucchi had joined the Navy when the war began. He was short, stocky, in his early thirties.

“He looked like an old guy,” Percy Robinson remembered of Delucchi. “I didn’t like him too well.”

“He spent half the day wanting to knock somebody down,” Cyril Sheppard recalled. “He was always challenging different guys: ‘If you think you’re big enough, come on out here, step forward’ and all that kind of stuff.”

“Very hot-tempered,” Joe Small added. “If things didn’t go his way, he was very quick to punish you for it.”

Sailors march onto the Port Chicago pier to begin their work shift.

Small managed to stay on Delucchi’s good side, though. The lieutenant quickly recognized Small’s leadership skills and assigned Small the job of marching outside the ranks and calling cadence.

“Left! Left! Left, right, left!” Small chanted as the division marched in rows, the pounding of boots on pavement falling into rhythm with his chant. After a short march, the men crowded into trucks—“cattle cars,” the guys derisively joked—and rode down to the pier to begin another day’s work.

On the long pier leading out into the bay, the men divided into five groups of about twenty men each. The ships they loaded had five hatches, and each team loaded bombs into one of the hatches. Each team broke into two squads. One worked on the pier, one in the ship’s hold—the huge, open storage area below deck.

Train tracks ran down from the base and out onto the pier, allowing boxcars full of explosives to roll onto the pier and stop beside the waiting ship.

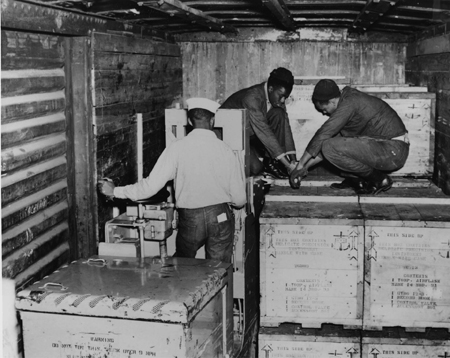

Above and below: Sailors unload crates of ammunition from boxcars at the pier.

“We’d open the boxcar doors,” Small described, “and the bombs would be stacked four, five, or six high inside the car.”

A couple of men climbed in, crouching between the top layer of bombs and the roof of the car. Using long wooden planks, they set up a ramp from the top of the bombs down to the pier, about eight feet below. Others, meanwhile, hung mattresses on the side of the ship—to cushion the blow in case one of the 500-pound shells rolled too fast down the ramp, sped across the pier, and slammed into the side of the metal ship. It happened all the time.

“You’d hear this all day long: BOOM! BOOM! BOOM-BOOM!” Percy Robinson remembered.

“And that would almost give you a heart attack,” said Freddie Meeks. Several times he asked the officers if there was any danger of an accidental explosion.

Their response was always the same: “Oh, no, don’t worry about it.”

Small heard this, but wasn’t convinced. He asked his lieutenant for a more detailed answer. Delucchi took out a booklet, flipped to a diagram of the 500-pound bomb they were loading and pointed out the detonator, which was attached to the head of the bomb. It was the detonator that triggered the explosion by sending a spark into the TNT packed into the bomb. The bombs the men were loading didn’t have the detonators attached yet.

“Won’t concussion blow this thing up?” Small asked.

“Impossible,” said Delucchi, pointing again to the diagram.

Once the bombs and crates of smaller ammunition made it down to the pier, the men rolled or lifted everything into nets. Each net was attached to a crane, which could be lifted by a motorized winch. Pulling levers in the winch, the winch operator lifted the sagging net into the air, guided it over the open hold of the ship, and lowered it down into the hold.

The crew in the hold unloaded the ammo in the ship. “You’d build yourself all the way up,” one sailor explained, “just packing until you found yourself way up on top.” After the first day of loading, the team would be working on top of a layer of bombs. They continued stacking explosives higher and higher until they reached the top of the hold.

At the very top, they loaded the “hot cargo,” as the men called it—650-pound incendiary bombs. Unlike the other explosives stacked in the ship, these had their fuses already attached.

The men at Port Chicago described the scene on the loading pier as frantic, stressful, loud, chaotic—bombs rolling and clanking together, winch engines chugging and smoking, nets swinging through the air, sailors shouting and cursing, officers urging the men on.

“We were all afraid of an explosion,” Small later said. “But there was very little that you could do about it. I mean, you had a day’s work to do.”

* * *

At first Joe Small worked on the pier, loading bombs with the rest of his crew. But he was fascinated by the winch operator job, mainly because it was the only work on the dock that required any skill. While the others were finishing lunch, he’d slip off to sit in the machine, practicing with the levers. Drawing on years of experience as a truck driver, he soon learned how to handle the winch.

A winch is loaded before lifting heavy bombs over the high sides of a ship.

One day, one of the Division Four winch drivers had to leave for a medical emergency.

“Hey!” someone on the pier called out. “Where’s the winchman?”

Small stepped up. “I’ll run it while he’s gone.”

He sat down, grabbed the levers, and got to work.

“So whenever they needed a replacement, they called on me,” Small recalled. “And eventually, I took over the job completely.”

That was typical Joe Small. Others in the division saw Small’s skill and boldness, and responded to it.

“He should have been anything but what they had him doing,” said a fellow sailor, expressing the common opinion in Division Four that Small should have been promoted to a position of more authority. “They just disregarded black people.”

The men thought Small should at least be made a petty officer, the highest rank given to black sailors at Port Chicago. Lieutenant Delucchi told Small he had the ability for the job, but was still too young.

Small didn’t get the promotion, or the private room and extra pay that went with it. But he got the responsibility, anyway. When Delucchi had a message to relay to the division, he went to Small instead of the division’s petty officer. When the men had a question or complaint they wanted presented to Delucchi, they went to Small.

“Look, you got a petty officer,” Small used to tell the men. “You got to talk to your petty officer.”

The men would curse the petty officer, say he didn’t know anything, didn’t have the guts to speak up to the white officers. So Small would give in and help.

“And that just put me in deeper,” he later said. He hadn’t asked for the extra work, and didn’t especially want it. “But I’ve never been one to shirk,” he said. “Once I commit myself, I’ll go through with it.”

* * *

Each division worked an eight-hour shift, and then headed back to the barracks while another took over. Bright lights lit the pier at night, and the loading continued nonstop, twenty-four hours a day.

The men’s lives were divided into eight-day segments. Three days of loading, then a “duty day”—laundry and other jobs around base—three more days of loading, then a day of liberty.

Like all the young sailors, Small treasured the chance to jump on a bus and get away from the base for a few hours, drink a beer in peace, maybe meet a girl. There was a town named Port Chicago about a mile from base, but it didn’t have much to offer.

“It was just a one-street place,” Robert Routh remembered; a few restaurants, a movie theater. “They didn’t want blacks there at all. The townspeople didn’t care for blacks.”

The nearest place with any sort of nightlife was Pittsburg, but the city had only one street with bars at which black customers were welcome. When they got off the bus in Pittsburg, the Port Chicago sailors were expected to walk a specific five-block route through a white neighborhood, a maddening maze of turns, to reach the “permitted” Black Diamond Street.

“Other streets we were found on, we were accosted,” Small remembered. “We had to answer questions as to why we weren’t where we were supposed to be.”

The fact that these men were wearing the uniform of the United States Navy made no difference.

Most of the men preferred to head for the big cities of Oakland or San Francisco, though it meant a longer bus ride. One liberty day, riding a bus for Oakland, Robert Edwards struck up a friendly conversation with two white sailors headed the same way.

“Let’s go over to the bar and have us a drink,” one of the sailors said when the bus reached the station.

The men walked into a nearby joint and ordered three bottles of beer. The bartender set two bottles on the bar.

“What happened to my friend’s beer?” asked one of the white sailors. “Aren’t you going to give him a beer?”

The bartender said, “We don’t serve niggers here.”

Edwards turned and walked out alone. He got on a bus and headed back to Port Chicago.

“We’re supposed to be fighting the same enemy,” he thought. “I don’t know who my enemy really is.”

After that, he spent his liberty days on base, in his bunk with a novel.

When he’d joined the Navy, people told him, “You’re fighting for your freedom!”

Now he wondered: “Where’s the freedom?”