Eight hours is a remarkably short period of time. It’s just 480 minutes or 28,800 seconds. As a professional, you expect that you will use those few precious seconds as efficiently and effectively as possible. What strategy can you use to ensure that you don’t waste the little time you have? How can you effectively manage your time?

In 1986 I was living in Little Sandhurst, Surrey, England. I was managing a 15-person software development department for Teradyne in Bracknell. My days were hectic with phone calls, impromptu meetings, field service issues, and interruptions. So in order to get any work done I had to adopt some pretty drastic time-management disciplines.

• I awoke at 5 every morning and rode my bicycle to the office in Bracknell by 6 AM. That gave me  hours of quiet time before the chaos of the day began.

hours of quiet time before the chaos of the day began.

• Upon arrival I would write a schedule on my board. I divided time into 15-minute increments and filled in the activity I would work on during that block of time.

• I completely filled the first 3 hours of that schedule. Starting at 9 AM I started leaving one 15-minute gap per hour; that way I could quickly push most interruptions into one of those open slots and continue working.

• I left the time after lunch unscheduled because I knew that by then all hell would have broken loose and I’d have to be in reactive mode for the rest of the day. During those rare afternoon periods that the chaos did not intrude, I simply worked on the most important thing until it did.

This scheme did not always succeed. Waking up at 5 AM was not always feasible, and sometimes the chaos broke through all my careful strategies and consumed my day. But for the most part I was able to keep my head above water.

Meetings cost about $200 per hour per attendee. This takes into account salaries, benefits, facilities costs, and so forth. The next time you are in a meeting, calculate the cost. You may be amazed.

There are two truths about meeting.

Often these two truths equally describe the same meeting. Some in attendance may find them invaluable; others may find them redundant or useless.

Professionals are aware of the high cost of meetings. They are also aware that their own time is precious; they have code to write and schedules to meet. Therefore, they actively resist attending meetings that don’t have an immediate and significant benefit.

You do not have to attend every meeting to which you are invited. Indeed, it is unprofessional to go to too many meetings. You need to use your time wisely. So be very careful about which meetings you attend and which you politely refuse.

The person inviting you to a meeting is not responsible for managing your time. Only you can do that. So when you receive a meeting invitation, don’t accept unless it is a meeting for which your participation is immediately and significantly necessary to the job you are doing now.

Sometimes the meeting will be about something that interests you, but is not immediately necessary. You will have to choose whether you can afford the time. Be careful—there may be more than enough of these meetings to consume your days.

Sometimes the meeting will be about something that you can contribute to but is not immediately significant to what you are currently doing. You will have to choose whether the loss to your project is worth the benefit to theirs. This may sound cynical, but your responsibility is to your projects first. Still, it is often good for one team to help another, so you may want to discuss your participation with your team and manager.

Sometimes your presence at the meeting will be requested by someone in authority, such as a very senior engineer in another project or the manager of a different project. You will have to choose whether that authority outweighs your work schedule. Again, your team and your supervisor can be of help in making that decision.

One of the most important duties of your manager is to keep you out of meetings. A good manager will be more than willing to defend your decision to decline attendance because that manager is just as concerned about your time as you are.

Meetings don’t always go as planned. Sometimes you find yourself sitting in a meeting that you would have declined had you known more. Sometimes new topics get added, or somebody’s pet peeve dominates the discussion. Over the years I’ve developed a simple rule: When the meeting gets boring, leave.

Again, you have an obligation to manage your time well. If you find yourself stuck in a meeting that is not a good use of your time, you need to find a way to politely exit that meeting.

Clearly you should not storm out of a meeting exclaiming “This is boring!” There’s no need to be rude. You can simply ask, at an opportune moment, if your presence is still necessary. You can explain that you can’t afford a lot more time, and ask whether there is a way to expedite the discussion or shuffle the agenda.

The important thing to realize is that remaining in a meeting that has become a waste of time for you, and to which you can no longer significantly contribute, is unprofessional. You have an obligation to wisely spend your employer’s time and money, so it is not unprofessional to choose an appropriate moment to negotiate your exit.

The reason we are willing to endure the cost of meetings is that we sometimes do need the participants together in a room to help achieve a specific goal. To use the participants’ time wisely, the meeting should have a clear agenda, with times for each topic and a stated goal.

If you are asked to go to a meeting, make sure you know what discussions are on the table, how much time is allotted for them, and what goal is to be achieved. If you can’t get a clear answer on these things, then politely decline to attend.

If you go to a meeting and you find that the agenda has been high-jacked or abandoned, you should request that the new topic be tabled and the agenda be followed. If this doesn’t happen, you should politely leave when possible.

These meetings are part of the Agile canon. Their name comes from the fact that the participants are expected to stand while the meeting is in session. Each participant takes a turn to answer three questions:

That’s all. Each question should require no more than twenty seconds, so each participant should require no more than one minute. Even in a group of ten people this meeting should be over well before ten minutes has elapsed.

These are the most difficult meetings in the Agile canon to do well. Done poorly, they take far too much time. It takes skill to make these meetings go well, a skill that is well worth learning.

Iteration planning meetings are meant to select the backlog items that will be executed in the next iteration. Estimates should already be done for the candidate items. Assessment of business value should already be done. In really good organizations the acceptance/component tests will already be written, or at least sketched out.

The meeting should proceed quickly with each candidate backlog item being briefly discussed and then either selected or rejected. No more than five or ten minutes should be spent on any given item. If a longer discussion is needed, it should be scheduled for another time with a subset of the team.

My rule of thumb is that the meeting should take no more than 5% of the total time in the iteration. So for a one week iteration (forty hours) the meeting should be over within two hours.

These meetings are conducted at the end of each iteration. Team members discuss what went right and what went wrong. Stakeholders see a demo of the newly working features. These meetings can be badly abused and can soak up a lot of time, so schedule them 45 minutes before quitting time on the last day of the iteration. Allocate no more than 20 minutes for retrospective and 25 minutes for the demo. Remember, it’s only been a week or two so there shouldn’t be all that much to talk about.

Kent Beck once told me something profound: “Any argument that can’t be settled in five minutes can’t be settled by arguing.” The reason it goes on so long is that there is no clear evidence supporting either side. The argument is probably religious, as opposed to factual.

Technical disagreements tend to go off into the stratosphere. Each party has all kinds of justifications for their position but seldom any data. Without data, any argument that doesn’t forge agreement within a few minutes (somewhere between five and thirty) simply won’t ever forge agreement. The only thing to do is to go get some data.

Some folks will try to win an argument by force of character. They might yell, or get in your face, or act condescending. It doesn’t matter; force of will doesn’t settle disagreements for long. Data does.

Some folks will be passive-aggressive. They’ll agree just to end the argument, and then sabotage the result by refusing to engage in the solution. They’ll say to themselves, “This is the way they wanted it, and now they’re going to get what they wanted.” This is probably the worst kind of unprofessional behavior there is. Never, ever do this. If you agree, then you must engage.

How do you get the data you need to settle a disagreement? Sometimes you can run experiments, or do some simulation or modeling. But sometimes the best alternative is to simply flip a coin to choose one of the two paths in question.

If things work out, then that path was workable. If you get into trouble, you can back out and go down the other path. It would be wise to agree on a time as well as a set of criteria to help determine when the chosen path should be abandoned.

Beware of meetings that are really just a venue to vent a disagreement and to gather support for one side or the other. And avoid those where only one of the arguers is presenting.

If an argument must truly be settled, then ask each of the arguers to present their case to the team in five minutes or less. Then have the team vote. The whole meeting will take less than fifteen minutes.

Forgive me if this section seems to smell of New Age metaphysics, or perhaps of Dungeons & Dragons. It’s just that this is the way I think about this topic.

Programming is an intellectual exercise that requires extended periods of concentration and focus. Focus is a scarce resource, rather like manna.1 After you have expended your focus-manna, you have to recharge by doing unfocused activities for an hour or more.

I don’t know what this focus-manna is, but I have a feeling that it is a physical substance (or possibly its lack) that affects alertness and attention. Whatever it may be, you can feel when it’s there, and you can feel when it’s gone. Professional developers learn to manage their time to take advantage of their focus-manna. We write code when our focus-manna is high; and we do other, less productive things when it’s not.

Focus-manna is also a decaying resource. If you don’t use it when it’s there, you are likely to lose it. That’s one of the reasons that meetings can be so devastating. If you spend all your focus-manna in a meeting, you won’t have any left for coding.

Worry and distractions also consume focus-manna. The fight you had with your spouse last night, the dent you put in your fender this morning, or the bill you forgot to pay last week will all suck the focus-manna out of you quickly.

I can’t stress this one strongly enough. I have the most focus-manna after a good night’s sleep. Seven hours of sleep will often give me a full eight hours’ worth of focus-manna. Professional developers manage their sleep schedule to ensure that they have topped up their focus-manna by the time they get to work in the morning.

There is no doubt that some of us can make more efficient use of our focus-manna by consuming moderate amounts of caffeine. But take care. Caffeine also puts a strange “jitter” on your focus. Too much of it can send your focus off in very strange directions. A really strong caffeine buzz can cause you to waste an entire day hyper-focussing on all the wrong things.

Caffeine usage and tolerance is a personal thing. My personal preference is a single strong cup of coffee in the morning and a diet coke with lunch. I sometimes double this dose, but seldom do more than that.

Focus-manna can be partially recharged by de-focussing. A good long walk, a conversation with friends, a time of just looking out a window can all help to pump the focus-manna back up.

Some people meditate. Other people grab a power nap. Others will listen to a podcast or thumb through a magazine.

I have found that once the manna is gone, you can’t force the focus. You can still write code, but you’ll almost certainly have to rewrite it the next day, or live with a rotting mass for weeks or months. So it’s better to take thirty, or even sixty minutes to de-focus.

There is something peculiar about doing physical disciplines such as martial arts, tai-chi or yoga. Even though these activities require significant focus, it is a different kind of focus from coding. It’s not intellectual, it’s muscle. And somehow muscle focus helps to recharge mental focus. It’s more than a simple recharge though. I find that a regular regimen of muscle focus increases my capacity for mental focus.

My chosen form of physical focus is bike riding. I’ll ride for an hour or two, sometimes covering twenty or thirty miles. I ride on a trail that parallels the Des Plaines river, so I don’t have to deal with cars.

While I ride I listen to podcasts about astronomy or politics. Sometimes I just listen to my favorite music. And sometimes I just turn the headphones off and listen to nature.

Some people take the time to work with their hands. Perhaps they enjoy carpentry, or building models, or gardening. Whatever the activity, there is something about activities that focus on muscles that enhances the ability to work with your mind.

Another thing I find essential for focus is to balance my output with appropriate input. Writing software is a creative exercise. I find that I am most creative when I am exposed to other people’s creativity. So I read lots of science fiction. The creativity of those authors somehow stimulates my own creative juices for software.

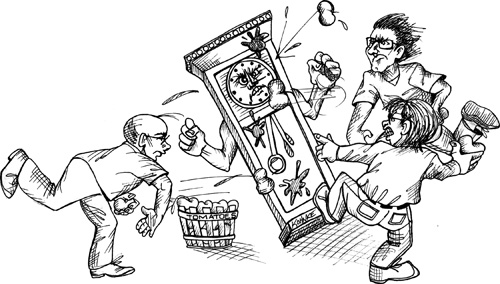

One very effective way that I’ve used to manage my time and focus is to use the well-known Pomodoro Technique,2 otherwise knows as tomatoes. The basic idea is very simple. You set a standard kitchen timer (traditionally shaped like a tomato) for 25 minutes. While that timer is running, you let nothing interfere with what you are doing. If the phone rings you answer and politely ask if you can call back within 25 minutes. If someone stops in to ask you a question you politely ask if you can get back to them within 25 minutes. Regardless of the interruption, you simply defer it until the timer dings. After all, few interruptions are so horribly urgent that they can’t wait 25 minutes!

When the tomato timer dings you stop what you are doing immediately. You deal with any interruptions that occurred during the tomato. Then you take a break of five minutes or so. Then you set the timer for another 25 minutes and start the next tomato. Every fourth tomato you take a longer break of 30 minutes or so.

There is quite a bit written about this technique, and I urge you to read it. However, the description above should provide you with the gist of the technique.

Using this technique your time is divided into tomato and non-tomato time. Tomato time is productive. It is within tomatoes that you get real work done. Time outside of tomatoes is either distractions, meetings, breaks, or other time that is not spent working on your tasks.

How many tomatoes can you get done in a day? On a good day you might get 12 or even 14 tomatoes done. On a bad day, you might only get two or three done. If you count them, and chart them, you’ll get a pretty quick feel for how much of your day you spend productive and how much you spend dealing with “stuff.”

Some people get so comfortable with the technique that they estimate their tasks in tomatoes and then measure their weekly tomato velocity. But this is just icing on the cake. The real benefit of the Pomodoro Technique is that 25-minute window of productive time that you aggressively defend against all interruptions.

Sometimes your heart just isn’t in your work. It may be that the thing that needs doing is scary or uncomfortable or boring. Perhaps you think it will force you into a confrontation or lead you into an inescapable rat hole. Or maybe you just plain don’t want to do it.

Whatever the reason, you find ways to avoid doing the real work. You convince yourself that something else is more urgent, and you do that instead. This is called priority inversion. You raise the priority of a task so that you can postpone the task that has the true priority. Priority inversions are a lie we tell ourselves. We can’t face what needs to be done, so we convince ourselves that another task is more important. We know it’s not, but we lie to ourselves.

Actually, we aren’t lying to ourselves. What we are really doing is preparing for the lie we’ll tell when someone asks us what we are doing and why we are doing it. We are building a defense to protect us from the judgment of others.

Clearly this is unprofessional behavior. Professionals evaluate the priority of each task, disregarding their personal fears and desires, and execute those tasks in priority order.

Blind alleys are a fact of life for all software craftsmen. Sometimes you will make a decision and wander down a technical pathway that leads to nowhere. The more vested you are in your decision, the longer you will wander in the wilderness. If you’ve staked your professional reputation, you’ll wander forever.

Prudence and experience will help you avoid certain blind alleys, but you’ll never avoid them all. So the real skill you need is to quickly realize when you are in one, and have the courage to back out. This is sometimes called The Rule of Holes: When you are in one, stop digging.

Professionals avoid getting so vested in an idea that they can’t abandon it and turn around. They keep an open mind about other ideas so that when they hit a dead end they still have other options.

Worse than blind alleys are messes. Messes slow you down, but don’t stop you. Messes impede your progress, but you can still make progress through sheer brute force. Messes are worse than blind alleys because you can always see the way forward, and it always looks shorter than the way back (but it isn’t).

I have seen products ruined and companies destroyed by software messes. I’ve seen the productivity of teams decrease from jitterbug to dirge in just a few months. Nothing has a more profound or long-lasting negative effect on the productivity of a software team than a mess. Nothing.

The problem is that starting a mess, like going down a blind alley, is unavoidable. Experience and prudence can help you to avoid them, but eventually you will make a decision that leads to a mess.

The progression of such a mess is insidious. You create a solution to a simple problem, being careful to keep the code simple and clean. As the problem grows in scope and complexity you extend that code base, keeping it as clean as you can. At some point you realize that you made a wrong design choice when you started, and that your code doesn’t scale well in the direction that the requirements are moving.

This is the inflection point! You can still go back and fix the design. But you can also continue to go forward. Going back looks expensive because you’ll have to rework the existing code, but going back will never be easier than it is now. If you go forward you will drive the system into a swamp from which it may never escape.

Professionals fear messes far more than they fear blind alleys. They are always on the lookout for messes that start to grow without bound, and will expend all necessary effort to escape from them as early and as quickly as possible.

Moving forward through a swamp, when you know it’s a swamp, is the worst kind of priority inversion. By moving forward you are lying to yourself, lying to your team, lying to your company, and lying to your customers. You are telling them that all will be well, when in fact you are heading to a shared doom.

Software professionals are diligent in the management of their time and their focus. They understand the temptations of priority inversion and fight it as a matter of honor. They keep their options open by keeping an open mind about alternate solutions. They never become so vested in a solution that they can’t abandon it. And they are always on the lookout for growing messes, and they clean them as soon as they are recognized. There is no sadder sight than a team of software developers fruitlessly slogging through an ever-deepening bog.