Chapter One

Young Provocateurs Invade Manhattan

Enfants Terribles: (Left to right): Tennessee Williams, Gore Vidal, and Truman Capote

It was right before Christmas in December of 1945. The streets of Manhattan were filled with Santas, often with a pillow stuffed into their red suits. The Salvation Army was out in full force.

The El rumbled along Third Avenue, and double-decker buses, called “Queen Marys,” rolled along Fifth Avenue. The Twentieth Century Limited pulled into old Penn Station every night as movie stars stepped off to be greeted by photographers and reporters—Paulette Goddard, Gene Tierney, Cary Grant, Joan Crawford, Rosalind Russell, Myrna Loy, and a newcomer, Ava Gardner.

Author John Cheever remembered “When the city of New York was still filled with a river light, when you heard the Benny Goodman quartet from a radio in the corner stationery store, and when almost everybody wore a hat.”

In midtown, servicemen were having one final blast before returning home. That was the Christmas that New York, and the rest of America, celebrated the end of World War II. Surrender had come with the dropping of the atomic bomb on Nagasaki, which led to the final collapse of the empire of Japan.

(Left to right) Gore, Truman, & Tennessee The only known photo of “The Unholy Trio.”

That December in New York had been blustery, cold, and gray, but there was optimism in the air. For the first time since the war, shapely women were seen wearing nylons. Sugar was no longer rationed. New Yorkers were buying cars fresh from the factories of Detroit, and used car lots were glutted with models from the late 1930s.

On Broadway, drama was flourishing, including a wildly successful “memory play,” The Glass Menagerie. It had been written by Tennessee Williams.

His future friend, Gore Vidal, had already written two novels, and his third, and most controversial, was on the way. Truman Capote was still struggling with his first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms, a book that would propel him into international fame and notoriety.

On the heterosexual front—“I was only a latent homosexual”—Norman Mailer was contemplating The Naked and the Dead, his 1948 novel about World War II. Violent clashes with the three gay writers lay in his future. In the meantime, Mailer proclaimed, “New York is the center of the universe, the only place for an artist to be. Of course, there is still Hollywood for those who want to be the next Lana Turner.”

“It’s a great time to be alive,” said Marlene Dietrich before boarding a train that would take her to Chicago and then westward to California. Once there, she hoped to pick up the pieces of an almost abandoned career. It had been interrupted by the war, when she had entertained Allied troops and had spoken out against Hitler and her Fatherland.

Just as Gore and Truman were enjoying the first taste of their oncoming fame, Tennessee, flush with Broadway success, found the New York brew too heady and was planning to flee. But, first, he paid a call on “the woman I wrote all my plays for her to star in.”

Before leaving to spend most of December in residence at Hotel Pontchar-train in New Orleans, Tennessee had stopped off for a “little bourbon and branchwater” at the home of Tallulah Bankhead. He was accompanied by a young marine he’d just picked up on the sidewalk, and whose name he could not remember.

Bourbon and Branchwater with Tallulah Bankhead

Ever since the summer of 1937, Tennessee had been a defender of Tallulah when she was under attack from his fellow Southerners. “I do not consider the alleged perversions and promiscuity of the star, Tallulah Bankhead, to be filth, but a robust natural life, boiling up to the surface.”

Tallulah Bankhead

He told Tallulah that “Broadway seems like some revolting sickness,” even though he was enjoying his first success there. “It’s centered around eating, then vomiting, and ultimately shitting—all at once. One’s ego becomes so sickly bloated with it.”

“Would that I, a mere mortal woman, was suffering through such a triumph,” she said. “The wolf is always at my door, dahling.”

Tennessee confessed that one of his major reasons for leaving New York involved his wish to overcome his sex addiction. “I can’t get any work done here. All I have to do is walk out on the streets around Times Square. Soldiers, sailors, marines, like this gentleman sitting here with us, and Air Force pilots, are returning home in droves, one horny bunch. I haven’t had so much sex since I departed wartime San Francisco, where I met countless young men, who’d left their wives or girlfriends back home, before shipping out to the Pacific theater—and perhaps death.”

It was inevitable that the three most famous homosexual writers in America—Tennessee Williams, Gore Vidal, and Truman Capote—would eventually meet in postwar America. Years later, after the 1940s had long ago been buried, they would communicate with each other mainly through their attorneys, threatening lawsuits.

Anaïs Nin

But early friendships were possible among this “Unholy Trio,” as each of them wandered, young and most often alone, down the lonely sidewalks of New York and through its cold canyons.

First came the historic meeting of 20-year-old Gore and 21-year-old Truman, who looked like he was twelve and spoke like a strangled child.

In Greenwich Village, Gore Vidal and Truman Capote were heading for the same party, where they would meet for the first time. The party would already be underway before they arrived. Fellow guests included an array of mostly struggling poets, novelists, playwrights, actors, and actresses, plus a flotsam and jetsam of people who lived on the periphery of the arts world in post-war America.

The meeting between Truman and Gore occurred in the skylit bohemian apartment of Anaïs Nin, a fifth floor walkup on West 13th Street.

She had already met and befriended a handsome young Gore Vidal, who was serving his final days in the military. Throughout most of them, he’d been stationed in the Aleutian Islands.

Anaïs, the party’s host, was already an underground legend of her own making. Unable to get her novels published in the 1940s, she had arranged to have them printed herself. At the time of her party, Gore had promised to get her novels republished by E.P. Dutton, where he was its youngest editor.

In The Erotic Life of Anaïs Nin, author Noël Riley Fitch defined her as “the ultimate femme fatale, a passionate and mysterious woman, world famous for her steamy love affairs and extravagant sexual exploits, most notably her simultaneous affairs with Henry and June Miller, and her bicoastal bigamous marriages.”

She was continuing to work on her endless diary, which she’d begun as a young girl and which her former lover, Henry Miller, had proclaimed would one day take its place alongside the writings of Marcel Proust.

At that point in her life, she viewed herself as an Earth Mother to a growing number of homosexual artists, including the young poet James Merrill.

Gore spent most of the party talking to Merrill, whom he’d first seduced when he met him as an undergraduate at Amherst. He later likened himself to “an older warrior to his unpublished Ephebe.”

The night of their first meeting, he’d gone to bed with Merrill, the son of Charles Merrill, co-founder of the brokerage house, Merrill Lynch.

James had published his first book at the age of sixteen. His wealthy father had paid the printing costs.

Author Christopher Bram defined Merrill as “pale, lean, and an aloof young man, cool and cryptic, full of courteous formality, suggesting that in some photos he looks like a suave extraterrestrial.”

Gore later suggested that Anaïs praised Merrill’s poems only because he wrote favorable critiques of her own prose.

At Anaïs’s party, Gore would later disappear into the night with Merrill to repeat a seduction that had begun at Amherst.

In 1977, Merrill would win the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. Later on, Gore would mock him for selling so few books.

“I’d rather have one perfect reader instead,” Merrill told him. “Why dynamite a pond in order to catch that single silver carp?”

In later years, especially during the 1970s, Gore, with a tinge of jealousy, watched as Merrill became one of the most celebrated poets of his generation.

Gore met another noted American poet at the party, Robert Duncan, and his lover, the expressionist painter Robert De Niro, Sr., father of the famed actor, Robert De Niro, Jr.

Duncan was a pivotal figure in Gore’s life, giving him some of the courage to write his gay novel, The City and the Pillar. In 1944, Duncan had written the landmark essay, The Homosexual in Society, comparing the plight of gay people to that of African Americans and Jews. It became a pioneering treatise on the plight of homosexuals in American society.

In the 1950s, Duncan’s mature works were consumed by the Beat Generation, who adopted him as a cultural hero. He also became a shamanic figure in artistic circles, especially in San Francisco, in a movement hailed as the “San Francisco Renaissance.”

When Gore complained to him about the hardships he’d experienced in the military, Duncan chided him. “You should have done what I did. When I was drafted in 1941, I declared myself a homosexual. There was no way the Army wanted me to share the shower with all those innocent young men from the Grain Belt of America.”

At the party, the other soon-to-be famous writer, a young Capote, had never heard of Merrill or Duncan, although he’d heard a lot about Gore.

Anaïs had never met Capote, who arrived on the arm of her friend, Leo Lerman, the writer and critic, who in the words of Anaïs, talked and looked like Oscar Wilde. At the time, Truman was using Lerman as his role model.

“Leo parries with quick repartée,” wrote Anaïs. “He is a man of the world who practices a magician’s tour de force in conversation, a skillful social performance, a weather vane, a mask, a pirouette, and all you remember is the fantasy, the tale, the laughter.”

She remembered Truman as a “small, slender young man, with hair over his eyes, extending the softest and most boneless hand. He seemed fragile and easily wounded.”

She had been impressed with Truman’s short story, Miriam, which had been published in Mademoiselle in its edition of June, 1945. It was the story of a sinister little girl who moves in with an older widow, gradually taking over her life.

Truman was not immediately introduced to Gore, until he had pirouetted around the room, showing off his black cape and his large black hat that evoked the popular concept of the headgear of a witch.

James Merrill

Anaïs must have wondered if Truman had adopted her own dress code. She often appeared in an Elizabethan hat like that worn by Sir Walter Raleigh, and she, too, wore capes around Manhattan, brightening many a gray day in Greenwich Village with her capes in tones of chartreuse, magenta, cerise, marigold orange, emerald green, or sapphire.

Anaïs Nin and a very young Gore Vidal: It began as a harmless flirtation and ended as one of the most venomous literary feuds of the 20th Century.

Truman came up to Gore. “How does it feel to be an onn-font-tarribull [enfant terrible]?” he asked.

Gore chose not to answer, but to ask a question instead. “Did you know that in Italian, capote means ‘condom?’”

Thus, one of the famous literary feuds in American letters was launched, although it didn’t heat up right away.

“Almost from the beginning,” Anaïs later said, “Gore and Truman sized each other up as future rivals. After all, there could be only one enfant terrible. Gore was almost a historian, dealing in facts, whereas Truman came from the Southern school of raconteur, meaning he never wanted a fact to get in the way of a good story. Gore camouflaged his homosexuality, whereas Truman used it to draw attention to himself. The more flamboyant he was, the more onlookers he attracted.”

The painter, Paul Cadmus, was at the party, observing both Truman and Gore. “Gore was formal and stiff, with military posture. Truman was the opposite. I always liked the little devil. He didn’t give a fuck what people thought of his high-pitched voice or anything else, including his outrageous opinions about anything. He was brave and gutsy.”

“At a time when all of America was afraid of J. Edgar Hoover, this Southern Magnolia (i.e., Capote) denouncd him at Anaïs’ party as a ‘killer fruit,’ a certain kind of queer who has Freon refrigerating his bloodstream,” Cadmus said.

Leo Lerman: Literary critic and literary lion

[The F.B.I director may have had a spy at Anaïs’ gathering. Just weeks later, Hoover would order his assistant and lover, Clyde Tolson, to set up a file on Truman. He would later demand that the F.B.I establish equivalent files on both Gore and Tennessee.]

Before the party ended, Cadmus had asked both Truman and Gore to pose in the nude for him. Truman accepted, but Gore rejected the idea.

The New York-born artist was notorious for his paintings and drawings of nude male figures, which combined eroticism and a style he referred to as “magic realism.”

In 1934, he painted The Fleet’s In for the Public Works Art Project of the WPA. It became one of the most controversial paintings of the Depression era, featuring carousing sailors, female prostitutes, and a homosexual couple. Such a public outcry arose that it was placed in mothballs and not allowed to be exhibited until the more tolerant year of 1981.

It is not known if Truman ever showed up to pose for Cadmus as an erotic nude model.

Gore was awed to see that within 15 minutes, Truman had most of the party-goers clustered around him as he told a most outrageous story:

Truman claimed that he’d been informed by the British actress Elsa Lanchester that “Noël Coward eats shit. Certain young boys are recruited in London to deposit their loads, and they’re put on a strict diet one week before they perform that service. When they’re squatted in position over Coward’s face, they are instructed to very slowly begin their bowel movement, allowing Coward time to taste and savor.”

“Truman didn’t stop there,” Gore later recalled. “He also claimed that that beautiful man, Tyrone Power, also ate shit.”

Paul Cadmus

What made that story believable was that this in-the-know group was already aware that Power and Coward at one time had been lovers. The accusation of shit eating, as relayed by Truman, originated with Elsa Lanchester, who was married to Charles Laughton, another alleged shit-eater. As bizarre as it seems, handsome Ty had seduced toad-like Laughton.

In reference to this incident, when Gore published his memoir, Palimpsest, in 1993, he claimed that to his horror, he later heard from several people that “I had been transformed into the source of this truly sick invention that will be grist to the satanic mills of Capotes yet unborn.”

The Fleet’s In was so controversial that the painting was suppressed for decades.

When Truman got around to actually talking to Gore, and not performing for the rest of the guests, he found they had certain similarities. “Both of our mothers were named Nina, and both of them were alcoholics,” Truman said. “We were both unloved as children. Both of us were amusing and bright, and fond of our own sex…at least in bed. And both of us were so terribly, terribly young, filled with such hopes and dreams that life had not destroyed for us, or made us cynical.”

“I wanted to be the firecracker of American writers. And Gore wanted that for himself. He also wanted to be President of the United States and the American version in letters of W. Somerset Maugham. Regrettably, he never found his literary voice except for his vinegary essays. His copy, unlike mine, lacked my sensitivity.”

During her “after-party analysis” with Gore, Anaïs claimed that “Truman wants to become one of my loved ones. But I’m already surrounded by enough childlike men, and I can’t take on another person. Truman reminds me of a Venus’s flytrap. I once saw one along the coast of South Carolina. Truman is exotic like that flower, but also devouring. He will feed on you, but give nothing in return.”

Gore met the following night with his closest friend at the time, interior designer Stanley Mills Haggart. Gore told him: “Capote gives homosexuality a bad name, and Anaïs does the same for self-love.”

Truman and Gore were not physically attracted to each other, but they began to “date” after the party at the apartment of Anaïs Nin. These dates were not romantic, at least not with each other. When they set out to explore underground New York, it was with the understanding that if either of them were able to pick up a trick, they’d be free to run off into the night with the object of their desire, with no questions asked the next day.

Truman Capote was accused of “spreading the most vile gossip” about Noël Coward (left), Tyrone Power (center), and Charles Laughton (right). However, some latter-day biographers have suggested that his shocking revelations may indeed have been true.

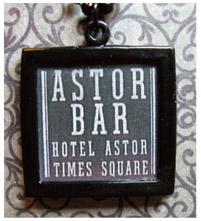

On their first date, Gore invited Truman to join him at the infamous Astor Bar at 7th Avenue and 45th Street, near Times Square. “Wear a red tie,” Gore instructed. “That will signal your sexual preference to the initiated.”

Gore later wrote that the Astor Bar was “the city’s most exciting place for meeting soldiers, sailors, and Marines on the prowl. No woman ever dared intrude into these male mysteries. After all, we had—all of us except Truman—won the great Imperial War, and, thanks to us, the whole world was briefly American.”

Since 1910, the Astor Bar had become legendary as a pickup spot at the “Crossroads of the World.” On its rooftop, beginning in 1940, Frank Sinatra had made early appearances with the Tommy Dorsey Band.

During the War, with so many U.S. military men in town, the Astor Bar experienced its greatest fame, welcoming thousands upon thousands of gay patrons in uniform—with the expectation that they be discreet, based on the standards of the time.

At the Astor, hundreds of men would be sardined, packed six deep around the long oval-shaped black bar within whose center bartenders ruled the sea of men on the make for each other.

A love object did not emerge for either Gore or Truman that night at the Astor Bar.

“The competition was too great,” Truman later recalled. “All the queens from Manhattan, the Outer Boroughs, and New Jersey, too, were making off with all the ‘seafood’ that night.”

After a quick hamburger at a joint on Times Square pushing papaya juice, Truman and Gore journeyed to the notorious Everard Baths, a place aptly nicknamed “Everhard,” which was said to operate because of frequent payoffs to the police.

From 1888 to 1985, these baths, housed in a former church, were the gay mecca of New York. Many great artists such as actor Emyln Williams, composer Ned Rorem, and even Truman himself, have written about their experiences cruising these baths. Other patrons have included Rock Hudson, Alfred Lunt, Lorenz Hart, Rudolf Nureyev, Dana Andrews, Montgomery Clift, Leonard Bernstein, Zachary Scott, and Dan Dailey.

In a memoir, Gore had nothing but fond memories of the Everard, even though it was mildewed, grungy, and dingy. “Military men often spent the night there because it was hard to get a hotel room in New York right after the war. This was sex at its rawest made most exciting. Newly invented penicillin had removed fears of venereal disease. Most of the boys knew that they would soon be home for good, and married, and that this was a last chance to do what they were designed to do with each other.”

Gore once published a paperback original under the nom de plume of “Katharine Everhard.” Although it was a straight romantic novel, the pseudonym was an inside gay joke.

Truman and Gore rented a cubicle and changed into the skimpy, knee-length white cotton robes offered as part of the entrance fee.

The Everard Baths, NYC

In The Gay Metropolis, author Charles Kaiser wrote: “You usually wore the robe loose with your cock hanging out. I guess you could have sex with as many as a dozen people. There were group scenes. There was a very impressive steam-bath room down in the lower level, as well as a swimming pool and a big sort of cathedral-like sauna room. It was very steamy and you could hardly see. You could stumble into multiple combinations.”

Like two voyeurs, Gore and Truman trolled the hallways, visiting the steam room, but finding nothing particularly appealing.

On the way back to their cubicle, they spotted an open door three down from their own cramped quarters. A well-built young man had just entered and had taken off his robe, lying nude on the bed with only a dim light illuminating his muscled body.

Both Gore and Truman surveyed what they called “a Greek God.”

“Adonis” accepted their request to enter. Both of the gay men came into the cubicle and fastened the latch on the door behind them.

Gore later told Stanley Haggart, his friend, what happened. “Truman and I devoured this handsome bit of man-flesh. But it led to our first major feud. I did a lot of the work myself, and we took turns sharing the riches. But at the last minute, Truman popped down on him and drained him dry to the last drop, although it rightfully belonged to me.”

After their communal sex, the young man was invited out to dinner at a restaurant in Greenwich Village.

He told Gore and Truman that he was an actor named Frank McCowan, and that he’d appeared in five movies—“Just small parts.” He claimed that Alan Ladd had discovered him, and he bragged that Ladd would be arriving in New York to spend four days in the city with him.

“The implication was clear that Ladd and he were lovers,” Gore claimed.

After Frank and Gore said goodnight to Truman, Gore learned that his newly minted friend had less than fifty dollars to live on for four nights. That’s why he was sleeping at the Everard, because it had the cheapest bed in town. Until Ladd flew in, four days hence, Gore invited Frank to live with him at his apartment.

“I’ll stay with you if you’ll give me all the sex I demand,” Frank said.

Gore gleefully agreed to those terms.

As he told Stanley, “The next morning, I got to enjoy the taste treat that Truman had greedily swallowed for himself.”

During the next four days, Gore and Frank bonded and would become longtime friends, seeing each other infrequently during Gore’s trips to Hollywood.

He learned a lot about Frank during their time together in Manhattan. When he was only thirteen, he’d stolen a revolver and was later arrested with it. A judge sentenced him to the California Youth Authority’s Preston School of Industry Reformatory at Ione, California.

A very inventive young teenager, he plotted his escape and pulled it off one night when there was a delay in the change of guards. He went on a rampage, robbing three jewelry stores before making his escape in a stolen Ford. He drove the car north toward Oregon, where he was arrested.

This spree involved crossing a state line, which elevated the caper to a federal offense. Frank was eventually recaptured and sentenced to three years in the penitentiary at Springfield, Missouri.

When he finished his sentence there, he was transferred to San Quentin on other charges that had been lodged against him during his rampage. He would be an inmate at San Quentin until he was paroled shortly before his twenty-first birthday.

He told Gore that in 1943, he’d gone horseback riding in the Hollywood Hills. There, he met Alan Ladd, who was just becoming famous as a movie star, after having appeared as the laconic gunman in This Gun for Hire (1942), co-starring with Veronica Lake. A closeted homosexual, Ladd was married to his agent at the time, Susan Carol Ladd.

The next time Gore heard of Frank, he’d changed his name to Rory Calhoun, and was seen escorting Lana Turner to a premiere. Frank (Rory) had been cast in movies which included That Hagen Girl (1947) alongside Shirley Temple and Ronald Reagan.

A bisexual, Rory would also become known for seducing his leading ladies, appearing in two movies with Marilyn Monroe, How to Marry a Millionaire and River of No Return.

By 1948, he’d married Lita Baron, and had become the father of three daughters. When she sued him for divorce in 1970, she named Betty Grable and Susan Hayward as two of 79 women with whom her husband had engaged in adulterous relationships.

At a Hollywood party after his divorce, Gore met up with Calhoun once again. Speaking of his divorce, he confided, “Heck, Lita didn’t even include half of them. For the sake of my masculine image, I’m glad she didn’t namemy all time favorite squeeze, Guy Madison.”

At that point in his life, Calhoun had delivered his most famous line: “The trouble with Hollywood is that there aren’t enough good cocksuckers.”

Anaïs Nin, in Volume Four (1944-47) of her famous diary, claimed that “Gore has a prejudice against Negroes.” In later years, the very liberal author would vehemently deny such an accusation.

In a memoir, he did admit that when he was growing up, his contact with African Americans was limited to servants. “The Gores were Reconstruction Southerners, and they got on well with our dusky cousinage in master-servant relationships, but they did not believe in equality.”

As the decades went by, Gore’s assertions became more indiscreet and ironic. “Half the mulattoes in Mississippi are related to the Gore family,” which included, of course, Al Gore, the former Vice President.

Anaïs had told Stanley Haggart that both Gore and Truman had been shocked at her party when she’d introduced them to two guests she indentified in her diary as “Rita, a Negro girl, and Don, a Negro guitar player.”

Two views of former jailbird Rory Calhoun, who climbed the lavender ladder to success, seducing some of the biggest stars, both male and female, in Hollywood

“He was the first movie star we ever seduced,” Truman said. “Gore and I shared him, although I got the best of Rory back when he was still named Frank.”

This surprised Stanley, who decided that both of these young writers needed greater exposure to the art world in New York. Stanley enjoyed friendships with many of the leading black artists of the late 1940s and 50s, especially dancers and singers. He would later be the art director for projects that featured Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne, and Alvin Ailey.

He decided to invite both Gore and Truman to his multiracial parties and to a gala where elegantly dressed blacks and whites mingled as equals.

Stanley’s parties in New York rivaled those of Anaïs Nin in bringing key players in the arts world together. He invited Gore and Truman to a party he was giving for Martha Graham, the dancer and choreographer.

At that party, Gore was introduced to a rising young novelist, James Baldwin, who was African American.

The press dubbed the appearance of Lana Turner (left) and Rory Calhoun (right) at a Hollywood premiere as “Blonde and Ebony.”

Rory would generate additional headlines appearing with yet another blonde in Hollywood through appearances with Marilyn Monroe in How to Marry a Millionaire and River of No Return.

Truman and Gore also met the rather flamboyant and eccentric Richard Bruce Nugent, a writer, painter, and key figure in the “Harlem renaissance.” In 1926, he’d published “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade,” a short story that was the first publication by an African American to openly depict homosexuality.

Nugent had once lived in Harlem in an apartment complex nicknamed “Niggerati Manor,” in which he’d decorated the walls with murals depicting homoerotic scenes.

Stanley also introduced Gore and Truman to Langston Hughes, an early innovator of the then-new literary art form known as jazz poetry. A poet, dramatist, and novelist, he was the leader of the Harlem Renaissance, an era which flourished [his words] “when the Negro was in vogue.”

Hughes was rather closeted, but exhibited a strong sexual attraction to his fellow black men, including writing beautiful poems to a male lover.

Gore and Truman also met Zora Neale Hurston, an American folklorist, anthropologist, and author best known for her novel, published in 1937, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Like Truman, she had grown up in Alabama.

Hurston told Truman that she was writing a novel [Seraph on the Suwanee, eventually published in 1948] about “white trash women.”

Sadly, Truman watched her decline into obscurity. In 1948, she was accused of molesting a ten-year-old boy. Although the case was dismissed and viewed as a false accusation, it seriously damaged her reputation. She ended up broke and in ill health, dying in a welfare home. The year of her death (1960) she was buried in an unmarked grave.

Stanley also took Gore and Truman to the annual black tie drag ball, an event inaugurated in the 1920s by Phil Black, Harlem’s most famous female impersonator. Josephine Baker, Billie Holiday, and Eartha Kitt were among the famous entertainers who’d attended this annual event in the past.

The setting was the dazzling Savoy Ballroom, with its crystal chandeliers and elegant marble staircase. The highlight of the event was when fashionably dressed drag artists vied for the title of “Queen of the Ball.”

At the ball, Stanley’s longtime friend, Phil Black, wearing a pink satin gown, came up to him and executed a pirouette. In reference to the gown, he said, “I made it myself, dahling.”

Drag artist Phil Black in the 1920s.

Stanley introduced him to Gore and to Truman. Black ignored Truman, turning his full attention to Gore. “You’re cute, honey,” Black said, reaching out to fondle Gore’s crotch.

Gore withdrew in horror, which Truman found “oh, so amusing.”

When Black departed, Gore turned to Stanley, saying, “This queen is outrageous. No one has ever done that to me before.”

Ordering champagne, Stanley sat with Gore and Truman watching the excitement reflected on their faces. The audience was mesmerizing, even to the jaded eye. Many men wore tuxedos, escorting as their dates other men clad in gowns and high heels. “The patrons were multiracial and multisexual,” Stanley said.

What caught the attention of both Gore and Truman was when Stanley introduced them to a stage performer known only as “Mandingo.”

He had originated in Martinique, and was the offspring of a Creole woman and a Frenchman from Toulouse who had settled on that island into a life as a planter.

Mandingo never liked to be called a Negro or referred to as black, preferring to identify his complexion as “café au lait.” He showed up at the ball wearing a sequined jockstrap. A performer at private parties and at exhibitions he was known for the size of his penis, which was nine inches when flaccid, rising to 13½ inches when erect. He also hustled on the side, renting his body to both straight women and homosexual men.

By the second bottle of champagne, Stanley became more daring, deciding that the time had come for Gore and Truman to cross the color line sexually. He proposed to Gore and Truman that he could arrange separate “dates” for them to be entertained by Mandingo. At first, they resisted, but curiosity and daring eventually won out. As the evening progressed, they became more relaxed.

“It was a big step for both of them to consider. It defied everything they’d been taught as teenagers,” Stanley said. “Not only miscegenation, but homosexual miscegenation, which was illegal in every state of the union.”

During the coming weeks, and on separate occasions, both Gore and Truman engaged in sexual interludes with Mandingo, who charged each of them $50 for his services.

Later, in the afterglow of seduction, Gore confided to Stanley, “For once, and perhaps never again, I completely lowered my inhibition. I learned what animal passion really means. I want to cage that beast within myself and never let him out again.”

James Baldwin

In contrast, Truman claimed, “I lived out my boyhood fantasy of being raped by a wild savage. The experience nearly put me in the hospital.”

Unlike Gore, Truman was so inspired by the experience that he wrote another one of his short stories, which he showed to Stanley. It was entitled Black Mischief and Dark Desires. Both men decided that no publisher at the time would touch it, so Truman destroyed it.

Whether it was true or not, Truman always claimed that Tennessee’s short story, Desire and the Black Masseur, was lifted directly from his experience with Mandingo which he’d relayed to the playwright.

For Truman, his experience in breaking down the color barrier led him to travel with Stanley to Port-au-Prince, capital of Haiti, in 1948. Here, he would find inspiration for his Broadway play, House of Flowers.

Perhaps to convince Anaïs that he had no prejudice against the American Negro, Gore showed up at her next party with his date for the evening, James Baldwin.

Before going out in public with Baldwin, Gore told Stanley that the writer is “as black as they come. He was born in a hospital in Harlem. He’s got a wide mouth, eyes as big as Joan Crawford’s, with heavy lids as droopy as those of Robert Mitchum. Call it a sandwich mouth and frog eyes. In the homophobic black world, he’s already been gang raped by hoodlums from Harlem.”

Gore later told Stanley that Baldwin was “a cross between Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bette Davis in A Stolen Life.”

At the party, Baldwin pointedly informed Gore, Anaïs, and Stanley, “I don’t want to be known as a Negro Novelist, and I certainly don’t want to be called a homosexual Negro Novelist.”

“All of us live with the poisonous fear of what others think of us,” Stanley said.

Gore later tried to get his editor at E.P. Dutton to purchase the rights to Baldwin’s first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain. The editor rejected the idea telling Gore, as a means of explanation, “I’m from Virginia.”

The brief fling between Baldwin and Gore quickly died. Stanley said, “Don’t call it love. Gore was trying to prove something to his friends, especially Anaïs.”

Before the friendship between Gore and Truman withered, they met every Thursday at one o’clock for lunch in the Oak Room of the Plaza. As biographer Gerald Clarke noted: “They niggled at their friends during the first course, devoured their enemies during the second, and savored their own glorious futures over coffee and dessert.”

Gore was struggling with his sexuality, even defining Anaïs Nin to friends such as Stanley Haggart as “my mistress.”

Truman had no such qualms. “I didn’t feel as if I were imprisoned in the wrong body,” he told Gore. “I didn’t want to be a transsexual. I just felt things would be easier for me if I were a girl. But I’ve always had a marked homosexual preference, and I never had any guilt about it.”

Even though pretending a surface friendship with Gore, Truman undermined him behind his back.

Marella Agnelli, the Italian socialite Truman would befriend in later years, figured it out: “Capote despises the people he talks about. Using, using all the time. He builds up friends privately and knocks them down publicly.”

When he met Bennett Cerf, publisher of Random House, at a party, Truman lashed into Gore. “From what I’ve seen, his writing is lifeless. There are those who say he might be another Hemingway. But really, my dear, let’s come to our senses.”

“Gore told me that while serving in the Aleutians, he suffered frostbite. He’s still not melted down yet.”

“I will give Gore credit for one achievement though,” Truman told Cerf. “He delivers the best known impression ever of Eleanor Roosevelt.”

He leaned in close to Cerf. “Gore has connections with the upper crust. He told me a secret that must go no farther than your ear to my ear. Gore claims that Mrs. Roosevelt is having an affair with Katharine Hepburn.”

[Actually, it was Truman, not Gore, who spread that rumor.]

Cerf had his own impressions of both Truman and Gore. He defined them as “a pair of gilded youths who thought they’d soon win Pulitzer Prizes followed by the Nobel Prize for Literature before either of them turned thirty. Judged by their work, Truman from the beginning found his voice in writing Other Voices, Other Rooms. Vidal is still struggling to find his voice. Incidentally, from what I’ve seen, Vidal’s novels are unreadable.”

“Speaking of voices,” Cerf said, “one of his schoolteachers in Alabama said Truman’s voice was identical to what it was in the fourth grade.”

During a private luncheon with his mentor, Leo Lerman, Truman confided secrets Gore had told him in confidence. “Gore confessed to me that he does not like women, with the possible exception of Anaïs Nin. I’m sure he’ll turn on her at one point. He finds women silly and giggly or else strident dykes. He also told me that he’s incapable of ever loving anyone except some boyhood friend of his who died in the war.”

“Another thing, Gore’s got this crazy obsession about the death of Amelia Earhart. Whether it’s true or not, he claims that his father financed that ill-fated around-the-world trip of hers. There’s more, although I hesitated to reveal it. What the hell…I will. Gore does a great imitation of Winston Churchill. He claims he found the wartime speeches of Sir Winston ‘raucously funny,’ although he has it from an authentic source that the prime minister has a big dick.”

The rich and famous in New York began to invite Truman to their parties. “He told the most delicious stories about everybody,” said socialite and party-giver Elsa Maxwell. “God knows what he said about me behind my back.”

“I remember one night Truman showed up at this party wearing some outrageous cape,” Maxwell recalled. “He had this large sapphire ring on. I don’t know if it were real or fake. When people admired it, he claimed it was a gift from John Steinbeck. At another party, I heard gossip that Truman claimed the ring was a love token from Ernest Hemingway. The more heterosexual the writer, the greater Truman’s claim that these authors were mad for the boy.”

These lies infuriated Gore, who ultimately doubted every word Truman uttered, including “the dots over the i’s and the crosses over the t’s.”

Stanley Haggart sounded a different note: “Truman lived in the world of the demimonde and was often privy to some occurrences going on behind locked doors among celebrities—closeted homosexual encounters among movie stars, adulterous affairs with many actors and actresses, and betrayals, including embarrassments we’d all like to forget. As a rough estimation, I’d say that half of what Truman told was fabricated. But much of it was true.”

“Anaïs and Gore would later dismiss Truman’s claim that he had a brief affair with James Dean before he became famous,” Stanley said. “But I knew that boast was true, because it occurred secretly in my Manhattan apartment.”

Gore was not alone in defining Truman as a liar. Another famous post-war novelist, Calder Willingham, began to size up Truman. He found him “attractive, clever, an excellent talker, but insincere, extremely mannered, snobbish even. He tries too hard to be charming. Also, he uses his homosexuality as a comedy, playing the role of the effeminate buffoon, making people laugh to call attention to himself. In any gathering, he wants to be at the center.”

“Both writers seemed obsessed with each other,” Stanley recalled. “When you were with Gore, he talked incessantly about Truman, mostly attacking what a fake he was. When you were with Truman, he spread vile gossip about Gore, some of it true.”

As time drifted by, Truman began to confront Gore with some of his shortcomings. If Truman met a young man who had gone to bed with Gore, Truman wanted to know all the details. One night at a drunken party, which Stanley attended with Gore, Truman came up to them.

In his high-pitched, drunken voice, he confronted Gore. “I hear from many sources that you’re just the lay lousé.”

“At last, Truman, you’ve got it right,” Gore admitted, to Stanley’s astonishment.

Later that night, Gore confessed a fuller review of his point of view to Stanley. “I pick up these poor young guys in the Times Square area and take them back to those Dreiserian hotels in the area, very seedy. They provide momentary pleasure for me, but I give them little in return. It’s only fair that they walk away from my rented bed with a ten-dollar bill as opposed to the street rate of five dollars.”

It was publisher Bennett Cerf who revealed what finally destroyed any pretense of a real friendship between Gore Vidal and Truman Capote. “Blame it on Life magazine,” Cerf claimed.

Right before Truman published his first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms, at the age of 23, in 1947, Life published a photo essay entitled—“Young U.S. Writers: A Refreshing Group of Newcomers to the Literary Scene Is Ready to Tackle Almost Anything.”

The editors plastered a full-page spread about Truman as the cover story’s lead. He was photographed amid the Victorian bric-a-brac of Leo Lerman’s living room. Beautifully dressed, hair artfully arranged, he was smoking a long cigarette. Life defined him as “esoteric, New Orleans-born Truman Capote.”

Since nothing Truman had written till then had been published, Life was obviously not awarding literary prizes. Truman was positioned as the featured writer only because his flamboyant picture generated the most attention. Gore would later describe it as “looking waxy, as if from under a Victorian glass bell.”

In the subsequent pages, smaller pictures were run of Jean Stafford, Calder Willingham, Thomas Heggen, and an unflattering likeness of Gore, with a caption identifying him as “a writer of poetry and Hemingway-esque fiction.”

When the Life article was published, Truman, in his exaggerated way, announced, “I’m the darling of the Gods. I’m the toast of New York, the only real city in America. I define a city as a place where you can buy a canary at three o’clock in the morning.”

With bitterness in his voice, Gore told a reporter, “Mr. Capote has launched himself as a celebrity, hardly as a writer.”

When Truman heard that, he shot back, “The Life article claimed that Mr. Vidal is twenty years old. Take it from me, she’s twenty-five if she’s a day.”

Bennett Cerf said, “Truman never forgave Gore for publishing Williwaw, his G.I. Joe novel written when he was only nineteen. It was a young soldier’s novel. The ending was like a cinematic rainbow and very influenced by Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage (1895).

Gore wrote: “The sky was blue and clear now and the sun shone on the white mountains. They walked back to the ship.”