Chapter Five

Sally Bowles, “Big Boy,” and The Man in the Green Tights

Christopher Isherwood (left) and Liza Minnelli (right) interpreting a character he created, cabaret entertainer Sally Bowles

“I want to meet the man who created the character of Sally Bowles,” Tennessee Williams told friends of the author, Christopher Isherwood. And so a meeting between these two gay writers came about at the celebrity-studded Brown Derby restaurant in Hollywood.

Tennessee had read and been enthralled with Isherwood’s novels, Mr. Norris Changes Trains (1935) and Goodbye to Berlin (1939).

Born in England, Isherwood at the time was labeled “an angry pacifist, a worldly spiritualist, and an ascetic sybarite.” He was considering becoming an American citizen, which he did in 1946.

Christopher Isherwood

By the end of World War II, Isherwood was the most celebrated gay writer in America. What Tennessee didn’t tell him was that he wanted to assume that role for himself.

Isherwood sized up the emerging competition, referring to Tennessee as “a strange boy, small, plump, muscular, with a slight cast in one eye—and full of an amused malice.”

Isherwood, who had been in Hollywood since 1939, was also appraised by Tennessee. “I was amazed at how short he was. I found him a ruggedly handsome blue-eyed Englishman with the build of a bantam boxer. He spoke in a thin, rather reedy voice. I ruled out romance. He wasn’t my type.”

“I am a lonely man wandering in a foreign country,” Isherwood told Tennessee. “I no longer have a country. I am a citizen of love.”

Sensing a kindred spirit, Tennessee immediately became confidential, discussing his sex life. “I have these uncontrollable sexual urges,” he confessed. “I cruise for young men day and night. This obsession interferes with my work. My libido is a painful burden to carry.”

Isherwood responded with confessions of his own. “For a while, I flirted with the idea of becoming a monk. That is, until I fell in love with this blonde-haired soldier. Celibacy went out the window the first night he fucked me.”

He even explained why he went to Berlin in 1931, where he met a little cocotte, Jean Ross, who became the inspiration of his fictional character, Sally Bowles. She would later become immortalized on the screen by Liza Minnelli in Cabaret (1972).

[The director of Cabaret, Bob Fosse, sent the film’s Fred Ebb-John Kander script, based on the 1955 play, I Am a Camera, first to Julie Andrews. But her agent wouldn’t even let her read it, rushing the script of Mary Poppins to her instead.]

“I didn’t find Englishmen very sexy, but I was powerfully attracted to working class German men,” Isherwood said. “I went to Berlin seeking love and found it in the arms of a handsome, muscled, blonde-haired, blue-eyed, sixteen-year-old boy, Heinz Needermeyer. When Hitler and the Nazis took over in 1933, I fled from Germany with Heinz at my side. We wandered through Europe in a kind of limbo, living in seedy hotels often filled with prostitutes and drunkards.”

Tennessee’s Libido: “A Painful Burden”

“When the British blocked me from bringing Heinz into London, we went to Paris, where he was arrested in 1937 for not having identity papers. The French deported him back to Germany, where he was arrested by the Gestapo for draft dodging. After serving six horrible months in prison, he was then forced to become a Nazi soldier. Life without my Heinz was devastating for me.”

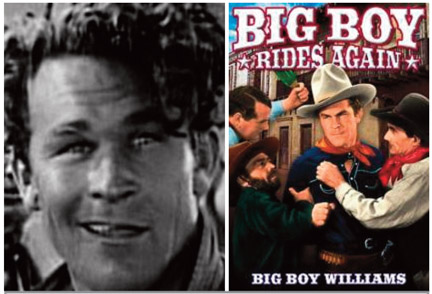

LOUD, LOUTISH, and BIG Big Boy Williams, with one of his movie posters

By the end of the lunch, the two authors, Tennessee and Isherwood, had bonded, leading to a lifelong friendship. But their date at the Brown Derby ended in a most unconventional way. Throughout their meal, they had been hawkeyed by a Western character actor, Guinn (“Big Boy”) Williams. He had been dining with Errol Flynn, with whom he’d starred as a “sidekick” in movies.

Perhaps goaded by Flynn, who was a prankster, Big Boy rose from the table, an impressive 6’ 2” of Texas manhood. He headed toward the table where Isherwood and Tennessee were seated.

Errol Flynn

Both writers were astonished when he pulled out a pocket knife from his pants and proceeded to slice off the tongues of their ties. The men were more astonished than frightened. “Do you collect ties?” Isherwood asked.

Big Boy grabbed his crotch. “You two faggots suck on this.”

“We can’t unless you whip it out,” Tennessee quipped.

Big Boy stormed toward the door, cursing under his breath. The maître d’ confronted him on his way out, asking him never to set foot in the Brown Derby again.

“That was the only tie I owned,” Tennessee lamented to Isherwood.

“I’ll buy you another one.”

Suddenly, as they looked up, it was Flynn himself who stood before them, looking “even handsomer than he did on the screen,” Tennessee recalled.

“Welcome to Hollywood, boys,” he said. “Sorry about Big Boy. It was just a little joke I conjured up to amuse myself on this hot, boring afternoon. No hard feelings.” He stuck out his hand.

Both writers shook his hand, Tennessee holding it for an extra long time.

Deliberately provocative, Tennessee said, “Is the rumor true that when you were fitted into those green tights to play Robin Hood, Warners insisted you wear a heavy duty jock strap so as not to give the men in the audience penis envy?”

“There are many rumors spread about me which are lies,” he said. “But you nailed me on that one.”

He fingered each of what remained of their ties. “You guys are good sports, and I’ll make it up to you by paying for your lunch.”

“I think we have a right to demand more tribute than that,” Tennessee said, eying Flynn’s ample crotch.

The actor winked at him. “Yes, I could do more to make you guys forgive me. Give me a rain check.”

That night, Tennessee invited Isherwood, his newly found friend, to go cruising with him along the blacked-out Pacific Palisades.

In this photo from 1938, before he went to Hollywood, Tennessee appears like a serious writer, which he was. For fun, he cruised the Pacific Palisades in a search for the type of “seafood” depicted above.

Isherwood later commented on that experience: “Tennessee could be quite courageous in approaching a sailor. He would single out his victim for the evening and just go up to him and make his pitch. Perhaps it was because of the war when most sexual restraints were removed, especially by those who thought they were going to die tomorrow. But during the time we knew each other in Hollywood, Tennessee often got his man, turning his apartment into a USO.”

“During the war years and beyond, Tennessee was constantly trying to find some fulfillment in the body of another man,” Isherwood said. “I don’t think he ever found what he was searching for during those hazy, drunkard, Dionysian nights he spent wandering, searching, forever on the move, seeking the next experience, even courting violence. So many of these young men were away from their homes, their mothers, their girlfriends, and they sought someone to love them wherever they could find it.”

Two days after their Brown Derby luncheon, Isherwood showed up at Tennessee’s apartment. He later said, “I had seen nothing like this since I visited a cheap abortionist in the slums of Berlin in 1932.”

“It was a dingy apartment where I found Tennessee sitting before a typewriter and wearing a yachting cap amidst a litter of dirty coffee cups, crumpled bed linen, and old newspapers. I learned that he works until he’s tired, eats only when he feels like it, and sleeps when he can no longer stay awake. He also told me he spent two or three hours every day on the beach.”

That night, when Isherwood and Tennessee went to a little fish house on the Santa Monica pier, Tennessee confessed why he’d been so drawn to the character of Sally Bowles. “She knows the difference between being fucked and being well fucked.”

When Gore Vidal first met Christopher Isherwood in a Paris hotel room in 1948, Gore was in his underwear and in bed. “We checked each other out for about an hour,” Gore later recalled, “and decided to become friends—not lovers.”

When Gore finally put on his pants, they walked to Les Deux Magots, the legendary café on the Left Bank. Jean-Paul Sartre and his mistress, Simone de Beauvoir, sat at an adjoining table.

Isherwood would remember Gore as “a big husky boy with fair hair and a funny, rather attractive face—sometimes he reminds me of a teddy bear, sometimes a duck. He’s typical American prep school. His conversation is all about love, which he doesn’t believe in—or rather, he believes it’s tragic. He is very jealous of Truman Capote and talks about him all the time. What I respect about him is his courage, though it’s mingled with a desire for self-advertisement.”

Even at this early stage in his life, Gore claimed he didn’t believe there was such a thing as a homosexual. “We are all bisexuals,” he proclaimed. He admitted that only hours before their meeting, he’d had sex with a Parisian hustler who had once worked in a bordello in Algiers before moving to France.

“And the night before that, I made love to a young Juliette Greco lookalike in my hotel room,” Gore confessed to Isherwood. “She compared my love-making to Picasso’s, and I was flattered…at first. ‘Oh,’ I said to her, ‘I’m a genius in the boudoir, too.’”

“Not at all,” Gore quoted her as telling him. “Like Picasso, you’re a very bad lover. Just in and out and back to work.” After she said that, the girl stormed out of Gore’s bedroom.

“At least Picasso and I have something in common,” Gore told Isherwood.

That autumn in Paris, after Isherwood got to know Gore, he wrote: “Gorefeels that life is too damn much trouble. Being with him depressed me, because he exudes despair and a cynical misery. He’s got a grudge against society which is really based on his own lack of talent and creative joy.”

When Isherwood, back in America, confided these concerns to Tennessee, the playwright responded, “Oh, Gore is just trying to defend himself against pain.”

After Paris, Gore and Isherwood saw each other only infrequently, although they wrote letters. March of 1955 found them both in Hollywood working side by side in office cubicles, turning out film scripts—Gore for Bette Davis, Isherwood for Lana Turner (as Tennessee had done before him, rather unsuccessfully).

Gore was adapting a teleplay, The Catered Affair, for the big screen. On his first day, he had met the play’s original author, Paddy Chayefsky. “He seemed very neurotic,” Gore recalled. “He told me he was haunted by a feeling of horror and unreality.”

“I deal with it by lighting one cigarette after another and sitting down to eat a large chocolate cake in one sitting,” Chayefsky confided. “I call it ‘chocolate by death,’ or perhaps it should be called ‘death by chocolate.’”

In the adjoining office, Isherwood was writing a screenplay for Lana Turner. The script was vaguely related to the life of Diane de Poitiers (1499-1566), the French noblewoman and courtier at the courts of Kings François I and his son, Henri II. As the “favorite” of Henri II, and a woman who reputedly retained her sexual allure and beauty through witchcraft, she became notorious throughout France.

In 1956, the Lana film was released as Diane by MGM. François I was played by Pedro Armendáriz, and a young and very handsome Roger Moore starred as the future king, Henri II.

Bette Davis in The Catered Affair

[Isherwood invited Tennessee to a screening of the film. After sitting through it, Tennessee did not have a comment until Isherwood asked him for his opinion. “I think Lana never looked lovelier,” Tennessee said.]

Gore confessed that he could not live on the meager royalties generated by his novels. That had led him to accept the job as a scriptwriter. At the end of their lunch in the MGM commissary, the two writers went for a walk around the studio lot.

They paused to sit down for a while beside the train under whose wheels Anna Karenina(Greta Garbo) had made her last dive, committing suicide.

Isherwood was despondent over his own career, urging Gore, “Don’t become a hack like me.” He also spoke of the difficulty he was having with the censors at the Breen Office. “They say I condone adultery. They want adultery to be punished by stoning, and they also think that homosexuals should be burned alive.”

In spite of his career problems, Gore claimed that he was “feeding my libido in Hollywood. Before six o’clock in the afternoon, all the hustlers along The Strip charge only ten dollars. I prefer sex in the afternoon anyway, so that suits me just fine.”

During their time at MGM, Gore and Isherwood lunched together almost every day, sometimes with a guest.

On one occasion, they dined “with a young Jewish producer. [Neither writer identified him.] The producer took exception with Gore comparing the plight of the Jews during the Holocaust with that of homosexuals rounded up by the Nazis.

“There was a difference,” Gore said. “The Jews wore yellow stars and the gay men had to wear pink triangles. But regardless of their badges, the end result was the same: the gas chamber.”

“The two persecuted groups should be allies,” Isherwood said. “Hitler killed six hundred thousand homosexuals.”

“But Hitler killed six million Jews,” the producer protested.

“What are you?” Isherwood asked. “In real estate?”

At one point, Bette Davis dropped by Gore’s office to see how work was progressing on The Catered Affair. She joined both Gore and Isherwood for lunch.

“I was surprised that over lunch, she brought up the subject of homosexuality and shared her views with us,” Gore said. “For such a supposedly sophisticated woman, her point of view shocked me.”

HISTORICAL DRAMA: Lana Turner, as Diane de Poitiers, getting kissed by Roger Moore as Henri II

“For the life of me, I can’t understand how anyone could be attracted sexually to a person of the same sex,” she told the startled writers. “It completely baffles me.”

[Throughout the life of Bette Davis, she never wavered from that position and always refused to support any gay causes. In private, she often made flippant homophobic remarks.]

Gore challenged her view, pointing out that at this stage in her film career her largest fan base consisted of gay men.

“That’s true,” Davis responded, “and I’m aware of that. I also know that I’m the one actress most female impersonators select to imitate.” The more she talked, the less homophobic she sounded, although at no point did she back down from her original comments.

“The homosexual community is the most appreciative in backing the arts,” Davis said. “They are knowledgeable and loving of the arts. They make the average male look stupid. They show their good taste in their support of my own efforts on the screen. Most of my fan mail today is from gay men. Even so, I still can’t understand why they want to sleep with each other. For the life of me, I will never condone that.”

“Don’t get me wrong,” Davis said. “I believe in equal rights for all—no matter the race, religion, or sexual orientation. At this point in my life, I’m also opposed to age discrimination, especially that dished out to fading movie queens.”

Through Isherwood, Gore met far more tolerant movie queens with far more sophisticated views about homosexuality.

But first, at his cliffside home in Malibu, Isherwood introduced Gore to his teenaged lover, Don Bachardy, whom the older writer had met on the beach when he was eighteen. Friends said Bachardy at the time looked no more than sixteen, if that. Gore referred to Bachardy as “thin, blonde, chicken-hawk handsome, an unformed neophyte who gradually discovered his passion for painting.”

At one party, Isherwood introduced Gore to Marlene Dietrich, who had been a great admirer of his Berlin novels. “Dietrich ruled the night from one corner of the room, Claudette Colbert on the opposite side.”

Gore had heard rumors that both Dietrich and Colbert had been lovers in the 1930s, and that there was a famous photograph showing Colbert sitting between Dietrich’s legs as they slid down a chute.

But their relationship had grown sour. When she spoke of Colbert to Gore, Dietrich seemed to hold the Paris-born actress in contempt, referring to her as “that ugly French shopgirl.”

Homosexuals, each forced into wearing a pink triangle, during their internment during WWII in a concentration camp, before being sent to the ovens.

Gore did not share Dietrich’s feelings and was delighted to meet Colbert later in the evening. Bachardy told them that in gay circles in Hollywood, Colbert was called “Uncle Claude. She lives deep in the closet.”

On the screen in such classics as It Happened One Night with Clark Gable, Gore had found Colbert the personification of gaiety and sophistication, who, when the script called for it, could also be provocative. “She stood before me showing only the left side of her face, which she considered her more beautiful,” Gore said.

Claudette Colbert (right), caught between Marlene Dietrich’s legendary legs

During the years to come, he always challenged people who labeled Colbert as a lesbian. She’d been married twice—once to Norman Foster, who later married Sally Blane, Loretta Young’s sister, and later to Dr. Joel Pressman—but Colbert always maintained a separate residence.

“Colbert should be called a bisexual,” Gore said. “I mean, Maurice Chevalier, Gary Cooper, Leslie Howard, Fred MacMurray, and Preston Sturges weren’t exactly females the last time I got their peckers hard.”

After they finished their respective scripts for Bette Davis and Lana Turner, Gore and Isherwood were assigned two new screen treatments. Isherwood’s job involved writing a screenplay about Buddha entitled The Wayfarer. It was never filmed.

In contrast, Gore’s script, based on the trial of Albert Dreyfus, was released in 1958. It starred José Ferrer. The New York Times warned that the audience “is likely to feel more frustrated by political obfuscation and courtroom wrangling than poor Captain Dreyfus was. Ferrer’s Dreyfus is a sad sack, a silent and colorless man who takes his unjust conviction with but one outburst protest and then endures his Devils Island torment lying down.”

Unusual for Gore, he maintained a friendship with Isherwood until the older writer died.

In 1984, on the occasion of Isherwood’s eightieth birthday, Gore visited him in Malibu. He later wrote Paul Bowles in Tangier, claiming that Isherwood had decided to emulate Tithonus.

[In Greek mythology, Tithonus, of the royal house of Troy, was kidnapped by Eos to become her lover. She asked Zeus to make Tithonus immortal, but she forgot to ask for his eternal youth. He did live forever, “but when loathsome old age pressed full upon him, he could not move nor lift his limbs.”]

In his report to Bowles, Gore claimed that Isherwood “looks amazingly healthy, preserved in alcohol, so life-like.”

But when Gore visited later that year, he painted a different portrait. “Chris is dying. He is small, shrunken, all beak, like a newly hatched eagle.”

Fresh from a trip to London, Gore complained about the fecklessness of the English. “It’s just like the grasshopper and the ant, and they are hopeless grasshoppers.”

Isherwood’s last words to Gore were, “So, what is wrong with grasshoppers?” Then he dropped off into a deep sleep.

On January 4, 1986, Isherwood died, suffering from prostate cancer. His body was donated to the UCLA Medical School.

In 1966, Gore reported that he was shocked when the first volume of Isherwood’s diaries were published. “He was very censorious of me, even when writing about the days when I thought we were having such convivial times together. You never know what friends really think of you until they publish their god damn diaries, Anaïs Nin being the best example of that.”

It was a hot day in late May of 1947 at Random House in New York City. Christopher Isherwood had just called on its publisher, Bennett Cerf. As Isherwood was being shown out by an assistant editor, a mannish-looking woman with short cropped hair, Isherwood asked if Random House had discovered any exciting new writers. “It’s always good to be aware of tomorrow’s competition,” Isherwood told the editor.

“There is one novelist we’re very excited about,” the editor said. “Truman Capote of New Orleans, who used to dance on a showboat on the Mississippi and also painted roses on glass. His novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms, can only be compared to Proust.”

As if on cue, Truman himself suddenly appeared in the hallway. As Isherwood remembered him, “He was like a sort of cuddly little Koala bear. His hand was raised high. Was I to kiss it?”

That was the beginning of a beautiful, sometimes tumultuous friendship that would last until Truman’s death.

In later years, Gore Vidal would proclaim that Truman’s most famous character, Holly Golightly, in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, “was merely a redrawing of the character of Sally Bowles in Isherwood’s Berlin Stories.”

As Isherwood later noted, “Fuck a comparison to Marcel Proust. This was a living, breathing character that stepped right out of the pages of Ronald Fir-bank. He was like a rare orchid growing in a hothouse in New Orleans, perhaps a man-eating plant that would later appear in Katharine Hepburn’s garden in Tennessee’s Suddenly Last Summer.”

“Truman seemed to throw a spell of enchantment over me, no doubt something he picked up at a Witch’s Sabbath.”

“Long after the editor left, we stood and talked and I did something I’d never done before. For myself and my lover, William Caskey, I accepted an invitation to visit Truman and his lover, Newton Arvin, at their cottage on Nantucket that July.”

Isherwood’s lover at the time, William Caskey, was a good-looking photographer in his mid-twenties who had been born in Kentucky. Isherwood had met him near the end of the war, and they had begun a serious affair. In Isherwood’s memoir (1943-1951), the writer claimed that Caskey “was the most un-inhibited homosexual; he seemed very tough yet very female. He loved getting into drag. He loved straight men. But he despised queens and didn’t think of himself as one. He wanted to fuck straight men, not be fucked by them. He proclaimed his homosexuality loudly and shamelessly and never cared whom he shocked.”

Truman’s lover, Professor Newton Arvin, also surprised Caskey and Isherwood when they arrived at Truman’s rented cottage in the village of Siasconset. “We were expecting some muscle-bound character rescued from some seedy gym in Brooklyn.”

Arvin was a middle-aged professor and critic, who had lost his job at Smith College when his homosexuality had been exposed. Newton was shy and retiring, preferring not to join in all the gay chatter and meals. He was spending most of his days and nights writing the biography of Herman Melville.

“You’re just as Virginia Woolf said you would be,” Truman once told Isherwood. “An appreciative, merry little bird.”

Actually, Truman was more intrigued by the pronouncement of another British writer, W. Somerset Maugham. The novelist had written “the future of the English novel lies in Isherwood’s pen.”

But Truman and Caskey were intrigued by each other. “Isherwood’s lover is completely uninhibited,” Truman said. “If such a thing were possible, he is even more shocking than I am.”

“You are so tiny,” Caskey said to Truman. “Do you also have a small dick?”

“A studly six inches,” Truman shot back. “Just ask Newton. He knows every inch intimately.”

Newton would later describe Truman’s penis in a letter: “One peppermint-stick, beautifully pink and white, wonderfully straight, deliciously sweet. About a hand’s length. Of great intrinsic and also sentimental value to owner.”

Isherwood was amazed that “Truman wasn’t the purple orchid I thought he’d be. He has strong arms and legs and is a good swimmer. He liked to bike around the island or go horseback riding. He has a sturdy body bronzed by the sun.”

That summer, Jared French, a photographer, snapped nude pictures of both Caskey and Isherwood, which they did not like.

“We looked like two hippos mating,” Isherwood later said. One of those photographs later appeared in Devid Leddick’s book, Naked Men: Pioneering Nudes 1935-1955.

Truman introduced Isherwood to the critic, Leo Lerman. He found Isherwood “quite delightful, with strange eyes and a delight in malice and in hurting himself.”

Truman entertained Lerman and other members of the Nantucket gay colony in the late afternoon. Mornings were reserved for writing Other Voices, Other Rooms. He complained to Isherwood that “the last pages are draining my blood. The final chapter is obdurate.”

“Finally, while we were still staying with him, Truman raced down the stairs one afternoon,” Isherwood said. “The last paragraph of that obdurate chapter had been completed.”

“It’s over,” he shouted in an almost hysterical voice. “With its publication, I’m going to become famous. Two hundred years from now, the world will be talking about Other Voices, Other Rooms.”

“Right in front of us,” Isherwood said, “he danced a jig of joy, evoking Hitler’s high stepping at the fall of France.”

In talking to friends, Isherwood later said, “Truman is completely outrageous. You never know from night to night what the entertainment will be. Friends dropped in from cottages nearby to be entertained by Truman. One night he put on an exhibit for testicular aficionados.”

Newton Arvin (left), and Truman Capote

He announced that a hustler would be arriving “with the world’s largest set of balls.”

After dinner and too many Manhattans and martinis, Truman answered the doorbell. A very young, very muscular, and rather handsome young man walked into the room. Introduced as Tony, he wore tight-fitting blue jeans and a form-fitting T-shirt, standing about five feet ten and weighing some 150 pounds. He pulled off his T-shirt to reveal broad shoulders and a ripply stomach.

“He stared at us almost defiantly, with the kind of blue eyes possessed by the Nazi soldiers who sent Jews to the gas chamber,” Isherwood later said.

“Slowly, very slowly, Tony unzipped his fly, revealing that he wore no underwear,” Isherwood said. “Gradually, he began to strip, lowering his jeans until his pubic hair burst into bloom. First he exposed a ‘hose-like penis.’ He saved the biggest show for last. He peeled down his jeans to his knees, exposing testicles that were like baseballs. No, larger than baseballs. They were gigantic. Almost a deformity. The image of the supreme male. Hitler would have abducted him and would have used him in one of his breeding camps.”

For the finale of the evening, Truman announced that Tony could later be found nude and lying spread-eagled on a bed in the guest room at the top of the stairwell. “All visitors are welcome, and the door will remain open until three o’clock,” Truman said. “That’s when Tony has to return home to his Portuguese wife and three children, all of them boys, as could be predicted. Tony’s been a father since he was fifteen years old. Those testicles actually started producing sperm, or so I was told, when Tony was only nine years old.”

***

Years would come and go; lovers would change, sometimes with the season, but Truman and Isherwood remained steadfast in their friendship. Sometimes there would be disagreements, but they would smooth things over because they genuinely liked each other.

They were not always appreciative of each other’s work. With friends, they often delivered private critiques. But unlike Gore and Truman, they did not deliver these insults face to face, only behind each other’s back.

When Isherwood finally got a copy of Other Voices, Other Rooms, he had reservations. “Unlike what I’d been told, Proust can snooze peacefully in his grave—nothing to fear from Truman. The novel seems to be mere skillful embroidery, unrelated to Truman and therefore lacking in essential interest.”

Over the years, Isherwood recalled some bizarre encounters with Truman. One such occurrence took place in the airport lounge of the Los Angeles airport as all of them were awaiting a plane to fly them to New York. Isherwood was traveling with his lover, Don Bachardy, and Truman was with William Paley, president of CBS.

The airport was fogged, and all flights were delayed. “Just call us the fog queens,” Truman said.

As the hours wore on, he announced, “I have this premonition of a disaster in the air. I’ve had these premonitions before. All of them come true.”

Paley stood up and faced him with anger. “God damn it, you’re getting on that fucking plane with us tonight whether you like it or not. If it’s going down, you’ll go down with us for alarming us like this.”

Obeying Paley like a stern father, Truman boarded the flight. Paley and Truman were seated in adjacent first-class seats, with Isherwood and Bachardy riding together in coach. At midnight, during the flight, Truman came back to visit Isherwood and his young lover. He scooted into the seat with them, sitting on their laps and throwing his arm around their necks.

“Are you bunnies scared?” he asked.

***

[At the time of Truman’s death in August of 1984, he’d lost most of his friends. Isherwood still remained loyal, however, and even attended the funeral services at Westwood Mortuary in Los Angeles.

It was later revealed that the aging Isherwood snoozed through most of the memorial service, finding the eulogies too long.

Actor Robert Blake, who had played Perry in the movie version of In Cold Blood, gave a speech that Isherwood found “too egomaniacal, having little to do with Truman’s life.”

Also delivering a long, rambling eulogy was a surprise speaker, bandleader Artie Shaw, former husband of Ava Gardner and Lana Turner. His punch line was, “Truman died of everything. He died of life, from living a full one.”

When Shaw returned to his seat, Bachardy nudged Isherwood, who stumbled to the podium. He gave the shortest eulogy of all. “There was one wonderful thing about Truman,” he said. “He could always make me laugh.” Then, as if remembering some long ago joke of Truman’s, Isherwood laughed loudly before Bachardy gracefully ushered him back to his seat.]