Erno was beginning to consider inviting Scott to the house some afternoon, so now he couldn’t help seeing it as if for the first time, the way Scott would. It was old and cramped—full of hiding places but so creaky as to make for really noisy hiding. Deep down Erno knew they were all a little old for hide-and-seek anyway, but he’d have to have something to suggest after breaking the news that the Utz kids had no video games or television.

The only board games they owned were Monopoly and Risk. Either one on its own might be considered by most sixth graders to be boring and overlong, so most sixth graders would not be able to appreciate what Erno and Emily had made when they combined the two into a bewildering supergame called Ronopolisk that was now in its fourth year and didn’t really encourage a third player. And wouldn’t it be a shame to stop now? Just when the Scottie Dog was poised to invade Poland.

So no TV and no games. No games but the games, and Erno wasn’t supposed to share those, either.

The discarded pink bow still lay like a scribble on the dining-room table. Was that significant? Was it a clue? Erno tried to tease some meaning out of its shape. It sort of looked like an ampersand.

There were sounds coming from the library, the dry swish of a broom against the floor. It was Wednesday, and on Wednesdays their housekeeper, Biggs, came to clean and cook, and mend anything that needed mending.

“Biggs!” Erno called into the next room. “Did Mr. Wilson say anything to you about this ribbon?” He looked down at the table, then back at the doorway, and was startled to find Biggs standing next to him.

“You all right?” Biggs asked in his dull way.

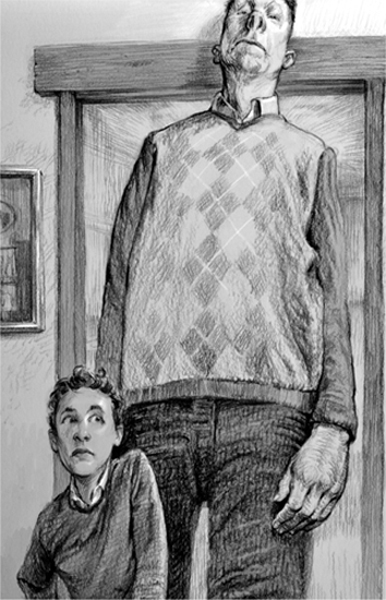

“Yeah. You sneaked up on me.” Even as Erno said this he could scarcely believe it, looking up at the man. What would Scott think of Biggs? He was, as always, enormous. More than eight feet tall, he stooped to get through every doorway. Even when he sat down, as he did now on a dining-room chair, he seemed too tall, and his knees pointed up at the ceiling like churches.

“Good day at school?” asked Biggs, scratching a huge hand over his cheek. As impressive as Biggs was, his hands still seemed two sizes too large, and were as thick and pink as hams. They were outmatched only by his feet. Which admittedly Erno had never seen, sure, but they had to be gigantic because why else would he wear such shoes? So long and tapered and to all appearances seaworthy. Like kayaks.

“School was fine,” Erno answered. “Did Mr. Wilson mention anything to you about this ribbon? Like, did he tell you not to touch it?”

“No,” said Biggs, scratching the back of his neck. “Just never disturb stuff like that.”

Erno nodded. Of course Biggs knew all about the games. As housekeeper he would sometimes uncover hidden clues meant for Erno and Emily, and he’d been asked in these cases to leave them as he’d found them.

“I think Emily’s figured it out already.” Erno sighed. “The new game, I mean. Or she’s figured out how to figure it out, which might as well be the same thing.”

Look at me, thought Erno. Talking about it. It felt good to talk about it. You could tell Biggs anything.

The only answer that came from Biggs was a sort of whuffling sound. He was sniffing the air, the great nostrils of his broad pug nose yawning wide. Erno had to stifle a yawn just looking at them.

“What is it?”

“Washing machine’s done,” said Biggs.

Erno smelled nothing but didn’t argue as Biggs rose and walked soundlessly away. He’d never noticed it before—everyone else in the Utz house made the old wood creak and whine when they moved. Everyone but Biggs.

Nothing was said about the scroll at dinner that night. Of course. They mostly sat in silence.

Mr. Wilson said, “Erno, could you pass me the square root of one hundred and forty-four peas?” So Erno began to portion them out onto his foster father’s plate using chopsticks that had been laid out for just that purpose.

“Emily,” he continued, “would you please spear your father another piece of moribund domestic avian muscle?” And so Emily served him some chicken. This was ordinary dining-room conversation in the Utz house, but Erno still strained to catch every word, worried that it might contain some clue. It made dinner exhausting.

It was days later when it hit him, and he called Scott right away.

“Archimedes is an owl,” he told him.

“He is?” said Scott. “I thought he was a Greek guy.”

“He’s that too. But … have you ever read The Sword in the Stone?”

“No. I’ve seen the movie.”

“There was a movie?”

“Sure. They show it sometimes on the Disney Channel.”

“Oh. Well, we don’t have a TV.”

“You don’t … what?”

“Have a TV. We’ve never had one.”

There was a longish pause, during which Erno occupied himself by imagining Scott’s horrified face. He was used to this kind of reaction. He may as well tell people that they didn’t have a toilet.

“Well, I haven’t seen the movie in a while,” said Scott. “I don’t remember the owl.”

“He can talk, and his name is Archimedes. He belongs to Merlin. That story we read the other day made me think of it.”

“Sooo … the claw of Archimedes rests…”

“On Merlin? On Merlin’s shoulder? I’m sure I’m onto something here. I … there was a new scroll sitting on my nightstand today when I got home.”

“What did it say?”

“IN YELLOW PAGES FIND THE NAME

AND PAY A CALL TO END THE GAME.”

“It was a hint.” Erno sighed. “I bet you a hundred dollars Emily didn’t need a hint.”

“‘In yellow pages find the name,’” said Scott. “You think you’re supposed to find the name Merlin in the original poem? Hold on.” Erno could hear Scott muttering to himself before his voice came back clear, and clearly excited. “In the first poem there are two Ms, eighteen Es, seven Rs, four Ls, and three each of Is and Ns. Two-one-eight, seven-four-three-three.”

“That’s just enough digits to be a local phone number.”

“It said to … what, make a call?”

“Pay a call,” said Erno. “Doesn’t that mean to visit someone?”

“The phone number’s worth trying anyway, isn’t it?”

“Yeah. I’ll call you back.”

Erno hung up, tried the number, then dialed Scott’s again. “Didn’t work,” he told him. “I got one of those ‘The number you’ve dialed is no longer in service’ messages.”

“Well, but listen to this: in the original poem, the first M is the twenty-fourth letter. The first E is the third. If you check them all like that you get two-four-three, four-one-four, two-three-three-four.”

“That’s long distance,” said Erno. “What area code is that?”

“It’s the Congo. In Africa. I just looked it up.”

Erno bit at a hangnail. “If this isn’t the answer, Mr. Wilson is gonna kill me for calling the Congo.”

“Can you do it as a three-way call?”

Erno could, and soon both boys listened as the number rang for the second, third, fourth time. Then voice mail:

“You have reached the voice-mail box for THIS ISN’T A CLUE, EITHER. If you’d like to leave a message—”

Erno opted not to leave a message.