CHAPTER 1 BURNOUT

THE AGE OF BURNOUT

The more things change, the more some things remain the same…

–ANONYMOUS

What the heck is going on??? In the past two years, I’ve been asked to present to a wide variety of organizations and audiences on the topics of overcoming burnout and building resilience. While I have lectured in this area for years, never have I had so many requests for these specific topics!

From student leaders in a major engineering college to literally thousands of pharmacists at an annual convention; from patient safety advocates to oncology nurses; from executive women to IT professionals preparing for a huge buyout; from an international women’s conference on disruption to coaching professionals in Manila—it’s all the same cry: HELP!

I wrote my first book years ago in order to understand my own burnout. So, in some ways, this feels like déjà vu—but bigger and meaner.

WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

My story: In 1984, I was prompted to write my first book, Work for a Living & Still Be Free to Live!, because I frankly hated my job, was exhausted to the max trying to appease a demanding manager, and was just plain miserable. A burned-out and unhappy camper, to be sure. I discovered I was not alone. Colleagues wanted to know how I did it—I just closed up my tent and left without anything in the offing to pay bills. (This is called walking out on faith!) They, too, were miserable and wanted to leave their respective positions.

I discovered the work of Dr. Herbert Freudenberger, a psychologist who introduced the term “burnout” into our vocabulary in 1974 and then wrote Burn Out: How to Beat the High Cost of Success.1 He defined burnout as “To deplete oneself. To exhaust one’s physical and mental resources. To wear oneself out by excessively striving to reach some unrealistic expectation imposed by one’s self or the values of society.” My expectation had been that I had to stay in a job that depleted my energy.

That surely was part of what I was experiencing—except there was more. I was engaged in work that had no intrinsic meaning for me. It took me almost three decades to realize that a lack of purposeful work can also lead to the very exhaustion Freudenberger described. This was what my colleagues some forty years ago were also experiencing. Be warned, however: Freudenberger also insisted that a state of fatigue can be brought about by “devotion to a cause, a way of life, or relationship that failed to produce the expected reward.” In short, he believed that underachievers would not necessarily experience burnout, but rather committed idealists, who set unrealistically high goals and whose energy was directed to only one part of life, would.

Unfortunately, the concept of “burnout,” as explored at the time by Dr. Freudenberger and Dr. Christina Maslach, a social psychologist and creator of the Maslach Burnout Inventory,2 was initially dismissed as pseudoscience. It was also relegated to the realms of the helping professions and found only in connection to this thing we call “work.”

Big mistake. Today, almost four decades later, burnout has become BIG stuff, with the “blaze” becoming uglier and more intense. The Maslach Burnout Inventory is now the most widely accepted and used measurement tool for burnout. The definition of burnout has been expanded to include the exhaustion of physical or emotional strength or motivation, usually as a result of prolonged stress or frustration.3

THIS IS A GLOBAL EPIDEMIC

Consider these statistics:

NORTH AMERICA

• The cost of stress and burnout to North American companies is estimated to range between $120 and $300 billion.4

• 58 percent of working Canadians report excessive stress every day at work.

• One US study found that work stress contributed to 120,000 deaths per year.

• Psychology Today (May 2019) reported that physician and health care provider burnout in the United States has reached epidemic proportions, with close to 50 percent identifying symptoms.5

• Burnout is responsible for up to half of all employee attrition. Employees are working more hours for little to no additional pay, recognition, or a sense of appreciation. Hence, they are searching for new jobs.

AUSTRALIA

• $34 billion is spent every year on burnout incidents.

• In 2013, the Australian Medical Students’ Association (AMSA) found that about one-third of all university students reported suffering from anxiety, harmful drinking, or eating disorders due to financial stress.

• Up to 75 percent of clergy suffer from work stress and 25 percent have reported stress leave or burnout.6

EUROPE

• In Europe, health professionals and educators experience the highest levels of burnout. In Germany, the epidemic resulted in the creation of the musical, Das BurnOut!

• A recent EU Labour Force Survey found that a quarter of the respondents—55.6 million workers—said their well-being had been affected by risks such as too much work, long hours, tight deadlines, and organizational changes.7

AFRICA

• Work-related stress and major depression, burnout, and anxiety disorders are costing South Africa’s economy an estimated R40.6 billion a year—equivalent to 2.2 percent of the country’s gross domestic product.8

• Maternal health staff found that 72 percent of workers suffer from emotional exhaustion.

• More than 75 percent of nurses in South Africa report fatigue, sadness, low energy, and frustration.

EAST ASIA

• Bloomberg Report stated that Chinese media states that about 600,000 Chinese a year die from working too hard.9

• Japan has even coined a word for death by burnout: karoshi. Government officials reveal that one out of every five workers is at risk for overwork. And there is also a word for suicide related to overwork: karojisatsu. For proven cases of either type of death, the government awards around $20,000 to victims’ families, and employers can pay up to $1 million in damages.

INDIA

• One out of every five employees of the company India Inc. is suffering from workplace depression, says a new survey, and medical experts blame it on a lack of support systems in both the workplace and personal circles.10

I could offer article after article about “burnout.” Just do a Google news search for this word, and you’ll find more than enough data to convince you that you are not alone. While you are looking, check out articles on “suicide.” Suicide rates are the highest they have been in the United States in three decades. Depression is at an all-time high. Even more frightening, students in high school and college are reporting anxiety, overwork, fear, and mental health challenges.

As I stated in the Introduction, in May 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) globally legitimized “burnout” by including it in the latest version of its International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems.11 They are quite careful to call it an occupational phenomenon. It is not classified as a medical condition.

A CAVEAT TO THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION’S DEFINITION

The WHO did not go far enough. It categorized burnout as a work-related hazard. In reality, there can be times when the workplace is our place of refuge because the demands in the rest of our life are enormous. Emotional and physical exhaustion can occur when caring for an aging parent, juggling the demands of school and work, or working through a divorce. Such times require more conscious choices for self-care. You might find yourself in this stage.

SO, GIVEN THE GLOBAL NATURE OF BURNOUT, HOW DO YOU STACK UP?

The following is a short survey I’ve compiled. (You’ll find a list of various and longer assessments in the Resources.)

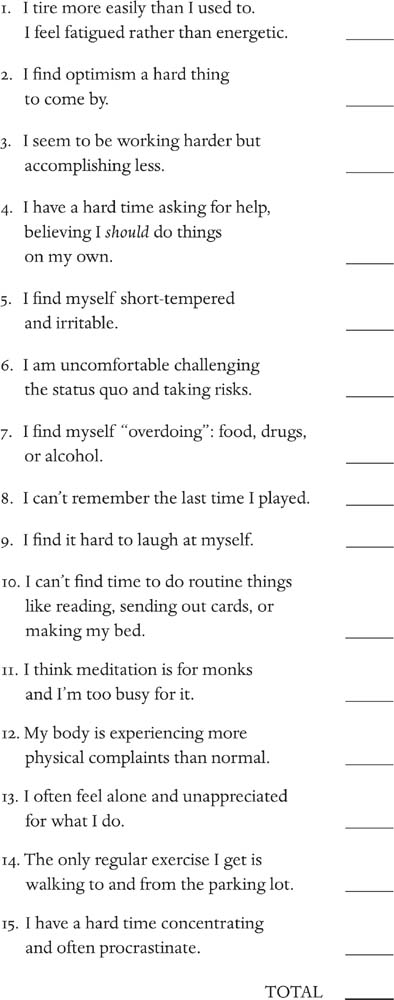

BURNOUT ASSESSMENT

Fill out the number that best describes your behavior.

1. Never 2. Seldom 3. Sometimes 4. Frequently 5. Always

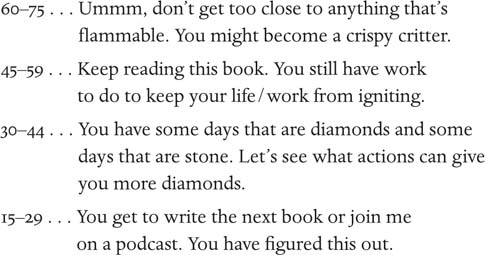

Please add up your numbers and see where you line up. Remember, this is a just a small sample survey and does not take into account the current context of your work and life. But it will give you some food for thought.