The Seinfeld Phenomenon and Its Cultural Impact

The Seinfeld phenomenon, as it were, didn’t occur overnight. While the show initially received a fair share of critical praise for being an incomparable, clever sitcom, the ratings didn’t exactly go through the roof of 30 Rockefeller Plaza. In fact, that distinctive Seinfeld buzz didn’t permeate the cultural ether until the fourth season and thereafter.

Thursday’s Child

At first, NBC couldn’t settle on the right spot for the show in its primetime schedule. Finally, in 1993, the network permanently moved the show to Thursday night to replace the long-running series Cheers, which was exiting the television stage after a successful eleven-year run. During its first few seasons, Seinfeld had been bouncing between Wednesday nights and Thursday nights. A considerable audience first noticed the show when it followed Cheers at 9:30 p.m. After moving into that show’s coveted Thursday night 9:00 p.m. slot, where it would remain, Seinfeld became not only a ratings-grabber but a veritable phenomenon. The Friday mornings after episodes aired inevitably found people of all ages, and from all walks of life, with Seinfeld on their brains. The show supplied a surfeit of breakfast-table banter, office water-cooler chitchat, and coffee shop repartee. Seinfeld rivaled sports talk in saloons and neighborhood gossip in salons. Seemingly overnight, the characters Jerry, George, Elaine, and Kramer had become sensations, and the actors who played them big stars who suddenly had the paparazzi nipping at their heels.

“They just wanted to do something fun,” Jonathan Wolff, Seinfeld composer, remarked to People magazine about the show’s two creators. Wolff remembered, though, that Jerry Seinfeld, Larry David, and the actors in the series really didn’t think the show was going to last more than several episodes.

Apprehensive NBC executive Warren Littlefield once asked, “Shouldn’t there be, like, any stories?” But what would make Seinfeld the huge hit that it eventually became—the aforementioned phenomenon—was exactly that. There weren’t any stories per se, at least of the traditional sitcom variety. Not a single Seinfeld character was ever going to get married and host a chaotic wedding where the best man forgets the ring or some such sitcom cliché. No babies were going to be delivered by Jerry or Kramer in their building’s malfunctioning elevator. Jerry wasn’t going to be asked to play a comedic Cyrano de Bergerac to help George win over a girl, although Newman did it for Kramer. No, not on Seinfeld—never! Describing Seinfeld’s plotlines—the show’s version of “stories”—is a whole lot more involved than recounting episodes of I Love Lucy, All in the Family, or Frasier.

The Seinfeld Alternate Universe

Jerry Seinfeld described to People magazine what the show was really about: “Imagine if all you do is hang out with your friends and have frequent romantic encounters, which don’t really hurt, and work is only sporadically dealt with—you don’t have to spend time at work except when it’s interesting and exciting—and basically you’re having a lot of coffee, a lot of lunches and dinners, a lot of swinging and a lot of hanging.”

The Seinfeld phenomenon was grounded in the show’s characters having a full twenty-two minutes each week to interact with one another and others in their exclusive universe. Questions concerning life’s mundane trivialities and oddities were regularly posed by Jerry, George, Elaine, and Kramer and hashed out by one and all. There were, in fact, many life lessons that we learned on Seinfeld, like the rules that apply to double-dipping a chip, appropriate times and places to urinate, and other such matters of etiquette. In the episode “The Pick,” Jerry’s girlfriend casts him aside because she catches him in the act of picking his nose. He defends himself by claiming that he was merely scratching his nose, not picking it, because there was “no nostril penetration.” This brand of multi-layered humor—dealing with the ordinary—was the essence of Seinfeld, and why so many people couldn’t stop talking about the show, quoting its dialogue and repeating its catchphrases.

Sein Language

Key to the Seinfeld phenomenon was the show’s contribution to the vernacular—i.e., its original catchphrases to describe particular behaviors, people, and events. Seinfeld has quite literally added to the English language—enhanced it with turns of phrases that will forever be remembered.

In the late 1970s, the ABC sitcom Happy Days, starring Ron Howard and Henry Winkler, was the rage. The character of Arthur Fonzarelli, “The Fonz,” was the Cosmo Kramer of his day on the popularity front. The show’s catchphrases, like “Aaaaaay!” “Sit on it!” and “Correctamundo,” were heard all over the schoolyards and on the streets. But it’s fair to say that the content of Seinfeld’s phraseology is somewhat more adult-oriented and has greater staying power.

What follows is a random sampling of the show’s Shakespearean contributions to the English language.

“Serenity now!”

While Ralph Kramden had his “Pins and needles, needles and pins, it’s a happy man that grins” mantra to repeat whenever he was feeling overly angry and upset, Frank Costanza, George’s father, had a mantra of his very own to help keep his blood pressure under control, in the episode “The Serenity Now.”

Frank: Doctor gave me a relaxation cassette. When my blood pressure gets too high, the man on the tape tells me to say, “Serenity now!”

George: Are you supposed to yell it?

Frank: The man on the tape wasn’t specific.

“Master of your domain”

This phrase originated from one of the all-time great Seinfeld episodes, “The Contest,” and refers to complete and utter abstinence vis-à-vis gratifying oneself. Engaged in a contest to see who can go the longest without masturbating, Jerry wonders how his friends are getting along in this taxing act of self-restraint. He poses the immortal question, “Are you still master of your domain?”

“These pretzels are making me thirsty”

This famous line, from “The Alternate Side,” specifically refers to Kramer’s speaking role—his one sentence of dialogue as an extra—in a Woody Allen film. He receives ample advice from his three friends on how best to deliver the line and maximize his moment on the Big Screen, which—alas—doesn’t come to pass.

Urinator

A Seinfeld-born term (from “The Wife”) that describes a person in a health club who urinates in the shower rather than take the time to walk to the bathroom. Reasoning that they’re all pipes leading to the same place, George has no problem being a “urinator.”

Shrinkage

This invaluable Seinfeld contribution to the English lexicon, from the episode “The Hamptons,” refers to what happens to a male’s private parts when he goes swimming or showers in cold water. When Elaine asks in astonishment, “It shrinks?” Jerry promptly replies, “Like a frightened turtle.”

Chucker

A Seinfeld gift to the patois, from “The Boyfriend,” and a descriptive word that all of us who attended high school and played basketball in gym class can appreciate. The word refers to someone who shoots the ball every time he gets his hands on it, and never, for one moment, considers passing it to a teammate. Although the preponderance of evidence says otherwise, George vehemently denies being a “chucker.”

Sponge-worthy

This is Elaine’s evocative phrase (from “The Sponge”) to describe the men she feels are deserving of her employing a finite contraceptive sponge during sexual intercourse. She cannot “afford to waste any of ’em.”

De-smellify

Jerry’s catchy turn of phrase in “The Smelly Car” for his high hopes that a valet parking guy’s nasty body odor would dissipate with the passage of time. Unfortunately for him—and many others—the “odor molecules” failed to “de-smellify” his vehicle this time around. In fact, the ghastly stench actually “gained strength throughout the night.”

George and Jerry in a scene from “The Smelly Car,” the source of the term “de-smellify.”

NBC/Photofest

Ma-newer

Courtesy of George, in the episode “The Soup,” we can now look at the word “manure” in a vastly different light. He says, “If you think about it, manure is not really that bad a word. I mean, it’s ‘newer,’ which is good, and a ‘ma’ in front of it, which is also good. Ma-newer, right?”

Baldist

Only on Seinfeld (in the episode “The Tape”) is there a special word for a woman who refuses to go out on a date with a man because he is follicly challenged. Jerry accuses Elaine of being a “baldist” because she’s never dated a bald man.

Yada yada yada

In “The Yada Yada,” George’s girlfriend reveals a penchant for leaving out the most important details in her stories and recollections with the expression “Yada yada yada.” The vernacular has never been the same since the episode aired.

Re-gifter

When Elaine dubs Dr. Tim Whatley a “re-gifter” in “The Label Maker,” the phrase took on a life of its own. Countless men and women admitted to being “re-gifters,” and just as many being the recipients of them.

Kavorka

Courtesy of the Seinfeld episode “The Conversion,” the “Latvian” word kavorka is in the Urban Dictionary. Kramer was said to possess kavorka, which translates as “the lure of the animal.” That is, a physical specimen completely irresistible to the opposite sex.

Shiks-appeal

Elaine Benes has done it again, supplying the world with a word, “Shiks-appeal,” to describe the attraction of Jewish men to non-Jewish women. In “The Serenity Now,” Elaine reveals the extent of her “Shiks-appeal,” receiving a mother lode of attention from Jewish males, including her former boss, Mr. Lippman, his young son, and Rabbi Glickman.

“No soup for you!”

After “The Soup Nazi” aired, the expression “No soup for you!” took the world by storm. A cantankerous soup peddler, who was a stickler for rules, uttered these now-immortal words.

Double-dipping

George’s bad habit of “double-dipping” his potato chips popularized this term. Inspired by his actions in “The Implant,” the Discovery Channel’s MythBusters examined whether or not “double-dipping” adds unwanted bacteria to dips. Their conclusion: It’s not a big deal because the dips—store bought and homemade—already contain traces of bacteria.

“Festivus for the rest of us”

Inspired by writer Dan O’Keefe’s father, who created Festivus—an alternative holiday to what he considered the overly commercialized Christmas holiday—this expression first appeared in “The Strike.” Frank Costanza is the television father of “Festivus,” which is celebrated on December 23, and he’s got his reasons for no longer celebrating Christmas. Since the episode first aired, increasing numbers of people very literally celebrate the holiday with its traditions of “airing of grievances” and “feats of strength.” An atheist group garnered press attention when they erected a Festivus pole—the holiday’s alternative to the Christmas tree—festooned with beer cans alongside a nativity scene and menorah in the Florida State Capitol building.

Seinfeld: The Human Comedy

Regarding the whole Seinfeld phenomenon that took the mid-1990s by storm, Wayne Knight, who played Newman, made the following insightful comment to People magazine: “Seinfeld is proof you can do a funny show about a group of people, none of whom has any decency, and strike a chord with the public deeper than any warm-and-fuzzy show.”

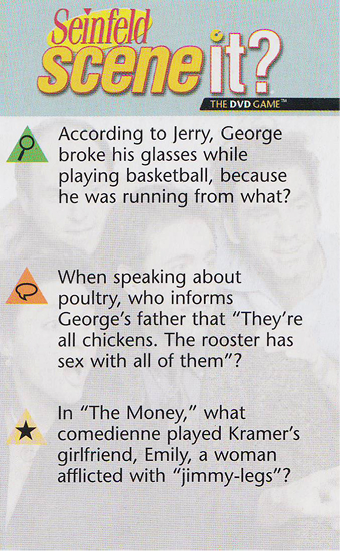

No show in the annals of television is more steeped in trivia than Seinfeld. Its characters, plotlines, and dialogue are the stuff of legend. Fans never tire of hashing out the show’s finer points. Card from the Seinfeld Scene It game.

This singular group of friends—the likes of whom had never before been seen on television—with their capacity to screw up one another’s lives, drew people to them. We just couldn’t get enough of these hilariously self-centered people. Week after week, we tuned in to see what Jerry, George, Elaine, and Kramer would do next. We talked about their antics with our family, friends, and co-workers:

• “Did you catch what George said last night about being a quitter?”

• “How about Jerry’s observation about the toxic combo of drinking and keeping secrets?”

• “Did you like the latest Kramer addition to the English language: ‘Wrong, Majumbo’?”

Actor and comedian Don Knotts once told talk-show host Phil Donahue that The Andy Griffith Show was the very first sitcom in which the show’s characters frequently veered off and spoke about things unrelated to the main storyline. Memorable scenes, for instance, involve Andy and Barney lazily sitting around on the front porch and reminiscing, even on one occasion lurching into their old high school theme song. Decades later, Seinfeld took this device to the next level. Life’s humdrum grind endlessly sidetracks Jerry, George, Elaine, and Kramer. They can’t help but observe the world they live in and offer their opinions and commentaries on the ordinary as well as the absurd happenings in life, like George expressing his disdain for having to ask a shopkeeper for change. He compared the unenviable task to asking someone to donate an organ.

In the overall picture, Seinfeld’s appeal was rooted in its singular ability to address the width and breadth of human relationships: friendship, sexual, parent-child, and employee-employer. Fans appreciated the show’s unique take on these relationships, and found many with which they could readily identify. Jerry breaking up with girlfriends for reasons ranging from George having seen her naked to her being liked by his parents were the kinds of things that fueled the show’s popularity. Fans tuned in week after week wanting more of the same. The off-the-wall antics and peculiar hang-ups of Jerry, George, Elaine, and Kramer amassed a bigger and bigger audience as the series progressed. There really had never been any sitcom characters quite like them.

The Seinfeld phenomenon was the genuine article. Ask anyone who was alive, alert, awake, and aware in the 1990s, and they’ll tell you how real it was. Even people who didn’t watch the show couldn’t help but end up in the crosshairs of Seinfeld chatter. And the fact that the show went out on top in its last season proves that the phenomenon had legs. It was also a testament to how groundbreaking and how funny the show was—and still is all these years later in syndication.