16

Connect

Help, Harmon is saying.

Candlelight brightens his hands as he angles his fork into a cut of cold meat. His lips are busy. Help, he repeats. Help.

I stare at him across the dining table. His Help is the gulp of an l and the pinch of the p, but I can’t figure out what he’s referring to. He doesn’t look distressed, neither does Mr. Holmwood who sits opposite him, and supplements his nephew’s monologue with a series of nods. There are no newspapers on the table to prompt his concern, only an opened envelope with the letter sitting on top. I strain my eyes to get sight of the handwriting and then wish I hadn’t. It looks like Mr. Bell’s writing.

Help.

Is it help that Harmon is asking for, or help we must offer? Harmon’s gesticulating becomes faster, and there is nothing I recognize on his lips. Mr. Holmwood drops his fork. It bounces onto the table and the floor, sprinkling snowy flakes of fish as it descends. I get up and wipe the mess, fetching a clean fork from the dresser. Placing it in Mr. Holmwood’s hand, I help him fold his fingers around the handle until he’s found a firm grasp.

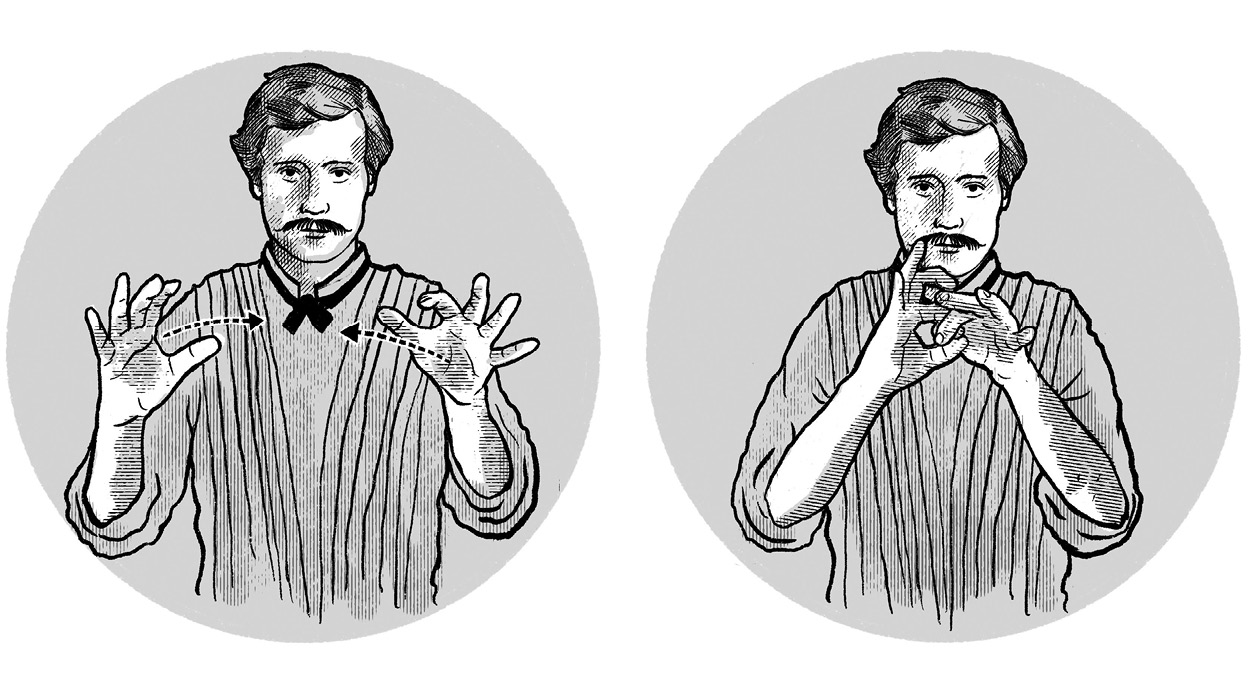

Thank you, he signs, touching the fingers of his other hand slowly to his chin. The simplest of signs and unlike Harmon, he has no qualms about using it. It’s a vestige from the days when Mrs. Ketter was with us, and Mama was dying.

I squeeze his shoulder, and Harmon watches as I take my seat again. His fury at me for ruining our call on the Bells has muted into a cool wariness. He hardly bothers making conversation on his fingers or in our notebooks. Since that afternoon, it’s been a litany of notes—short and functional—and long spells of silence.

When I’m seated, he writes a few lines in his notebook, sliding it across the table with the open letter. “We are discussing some correspondence I have just received from Mr. Bell today,” the notebook informs me.

I take up the letter and Mr. Bell’s words sharpen between my hands, bringing his haste into view. I try not to let my thoughts spring ahead with my hopes, but I can’t help myself. What might it contain that I can tell Mr. Crane? At first glance, he appears to be responding to a request Harmon has made about the Telephone franchise. If Harmon wants to pursue the prospect further, Mr. Bell has replied, he would do better to take it up directly with the Bell Telephone Company. He himself is sick of the Telephone and its business and doesn’t want to waste a penny nor a minute further on it. “The position of an inventor is a hard and thankless one,” he has written. “Let others bear the anxiety and expense of it!”

No wonder Harmon is aggrieved. All those letters he has written to the schools for deaf children, helping Mr. Bell secure contacts. He’s told his potential customers about his close connection to the inventor of the Telephone, only for Mr. Bell to declare no especial loyalty and pass him over to his business partners. Now he finds himself in a swamp of humiliation, and the only route out is a thin insistence on what can be saved. We must help him.

But the next passage makes me forget Harmon’s concerns altogether. “I shall go,” Mr. Bell has continued, “to Greenock in Scotland where I shall set up a school for deaf-mutes. My assistance there is much needed.”

I hasten through the details; in essence a small school for a select group of children, but in its successful establishment he envisions a better education for the thirty thousand deaf-mutes of Europe. After all, he writes, isn’t this his life’s work?

I can almost see the small classroom in which Mr. Bell stands at the blackboard, scratching out Visible Speech. His face enlivened with focus while the children gaze upon the symbols, on this new teacher, this mystery of speech which, they have been told, needn’t be a mystery at all. Their hands are in their laps, and they know they must keep them still. Not a question or a thought must stir on them. Their mouths are moving instead, and they are watching for someone to tell them they are doing well. Isn’t that what Mr. Bell is seeking too? He’ll go as far as Scotland to feel useful and find comfort of some kind. The thirty thousand deaf-mutes of Europe come to his aid, as he goes to theirs.

“Lastly,” the letter finishes, “I no longer require a demonstration from Miss Lark for the talk at the Anthropological Society. If you desire to see me before I depart to Scotland, I will be at the Royal Society but it will be my last appointment concerning the Telephone.”

I don’t dare glance at Harmon. Did my behavior when we called result in this cancellation? Mr. Bell doesn’t trust me once again. Besides, there is new alarm rising from the waves of my relief. How can I continue with Mr. Crane’s task if Mr. Bell desires to put more distance between us? I feel a reluctant appreciation of Harmon’s anger toward me: my actions on our last meeting led to this. A wrong move, a false step. Fury burns in my breast, but this was my doing.

I say, We don’t need to help Mr. Bell.

My voice sails between the salt and pepper mills, glancing off the water jug and coffeepot, the plates and the cutlery, until it lands with a shiny startle in Harmon’s eyes. Even Mr. Holmwood turns his head.

Mr. Bell will calm down, I continue. He always does.

There must be a wobble in my voice because Harmon seems to think I’m the one who needs calming. He fetches Mr. Bell’s letter and stops to rest his palm on my shoulder as I’d done on Mr. Holmwood’s. His hand is as light as a new lover’s kiss. I’m surprised to feel coils of remorse loosening through me, an answering song to the gentle pressure of his hand. Didn’t I bring this on myself? A split created between us the moment I wrote to Mr. Crane, and dared glance back at the past. But a quick spill of anger sours this worry. Mrs. Ketter, and Harmon’s dismissal of her, has been unspoken between us for all these months. Our notes go to and fro, papering over that particular silence, so now its shadow goes as long as Mama’s death.

I reach for the notebook. “We could offer to give a speech at the Royal Society,” I begin. “A demonstration of Visible Speech down the Telephone. Wouldn’t that be an attraction? It will make amends for our last visit and show our gratitude for the favor he has shown us.”

With difficulty I pass the page to Harmon. I want to rip the words away as he nods slowly. He is thinking: what a crowd-pleaser, what a proposal. But he doesn’t trust me, and I can’t say if Mr. Bell will either. I feel an agony of waiting. I want him to tell me that I don’t have to do such a thing, to take the stage and perform Visible Speech again. But I also want him to write yes, so that Mr. Crane’s task may continue, our connection with Mr. Bell restored for long enough for me to complete it. And I want us to be content, but I don’t know if a Yes or No will bring it.

His decision comes in one neat line. “I will write to Mr. Bell and see what he thinks.”

My last report to Mr. Crane was brief. I didn’t tell him what had happened when we called on the Bells, because my thoughts were too clouded by what Mr. Bell had revealed about the smoked glass. Was Mr. Crane aware that Frank had tried to deceive him with damaged goods? Did he know the glass had been altered when he bribed me with it? But it was Frank’s mark that I wished to understand. I spent hours examining the craggy contours of this new line. It was carefully drawn, with an exact cluster of peaks in the middle. I tipped it back and forth in front of the window but couldn’t make anything from it. Instead, I turned my thoughts to Mabel’s face and how she had stared over her husband’s shoulder as I said Mystery and Mr. Gray. Her alarm was evident. What had she seen? I wrote Mr. Crane asking for more Visible Speech symbols.

His reply came back to me with a list on a separate sheet. “I enclose the translations you have requested,” he wrote, “although I must point out that I have already given you the technical words that relate to the Telephone and cannot see the relevance of a single one of these words bar the last one, which I concede was not included on my original list. Have you had sight of this word?”

The letter showed his nervousness: he fears I’ve lost the plot.

I take out the list and run my finger down the English words which are set next to their Visible Speech symbols. There’s Mystery through to Misery, Obituary, and Big Story. I had tried them in a mirror before asking for translations, since they all bear a similar shape to Mr. Gray.

Finally, the last word: Mercury.

Mabel in the Bells’ parlor, her face frowning at mine. The pale horror as she drew back. We had already spoken of Mr. Gray that evening, and what should be so perturbing about the word Mystery? She had seen something else on my lips.

I fetch an envelope from my mother’s travel case, which is disguised as one of her letters. After my last meeting with Mr. Crane in the Horticultural Gardens, I made a copy of the note he showed me about Mr. Bell’s patent. I wrote down as much as I could remember, grateful for my copyist’s memory that could hold on to several sentences. “For instance,” my messy script reads, “let mercury or some other liquid form part of the circuit.”

In my pocket mirror I start examining the Visible Speech symbols. Mercury, I say, watching the shape press and push out my lips. Mr. Gray, Mercury, Mr. Gray.

There’s a flash in the picture-glass hanging in the hallway. I’d forgotten to shut the door. Is someone hiding at the door frame? Hasn’t Harmon left for the Department Store? Then I see his gloves on the hallway side table beneath the picture: he has come to fetch them and discovered me saying Mr. Gray’s name and Mercury perfectly and repeatedly, apparently to myself.

As if my outburst at the Bells’ wasn’t bad enough.

I shove Mr. Crane’s letters under some papers and hold my breath. Perhaps Harmon won’t have recognized my voice since I was reeling off Visible Speech. But who else could have spoken? I wait, frozen in my seat. The reflection hesitates and then he slides into view, taking his gloves and softly whacking his other hand with them, as if he’s beating out a rhythm for his thoughts. His brow is lowered and his lips are folded by the jut of his chin. The word Mr. Gray dances in the air between us, for a second time this month.

You are not off to work? I say, but I can’t look at his face for long. His thoughts are gathering in his expression. He reaches for some paper, and stoops down to the desk so that his sentences make the same awkward angles as his arms and elbows, which knock into me as he writes.

“I have written to Mr. Bell to suggest that we present Visible Speech at the Royal Society.”

Good, I say, trying to sound pleased.

But Harmon only looks irritated. He shoves the paper to me a second time. “I thought you said you didn’t know anything about the Telephone,” he has written, “and yet you seem to have developed some sort of idea about Mr. Elisha Gray. His name is not even in the papers.”

I glance at him, still bent double at my elbow and refusing to look at me; his body spelling out his complaint. See, how he must ask me like this. See, how much our modes of talking are a hindrance.

“Shall I find a chair?” I write back. “You do not look comfortable.”

His lips: No.

I look uneasily at his question again. “You told me about him in Philadelphia,” I write, after a moment. “And I think in Boston there was an article about his work. That’s all I know.”

He looks up from the page and says something. He’s so close, I can smell the coffee on his breath, but I miss most of his words, apart from the last one. Mr. Gray, he says.

His lips: Mercury.

I look down at the desk. I never told Harmon how I met Mr. Gray in Philadelphia. How could I when I was with Frank, and not where I was supposed to be?

His eyes are flinty, and I sit very still. Sit pretty and sit tight, Adeline used to say. It’s your best hope. I didn’t care if I was sitting pretty but I was sitting awful tight.

“I have been giving our notebooks some thought,” he writes. “Perhaps it would not hurt for me to learn a few signs to use with my finger-spelling.”

This stumps me completely. The sign language? A bubble of hope rises in me in spite of myself. “As it happens,” he continues, “Mr. Bell told me that there is a person on his legal team who knows signs but is hearing himself. His name is Crane. Perhaps he can help.”

He hands me the note and finally stands up, a victor rearing above the spent match. His gaze presses into the back of my neck, bearing down his satisfaction, but I’m only grateful that he can’t see my face, as questions ram my thoughts. Mr. Bell’s legal team? Is that how Mr. Crane got sight of the English patent? Because he had express permission to view it? I try to bring to mind everything Mr. Crane has told me as I also try to recall every letter I might have left around for Harmon to see. My travel case. Harmon must have been rooting through it.

“I have never heard of Mr. Crane,” I write back, making my lines tidy and neat beneath the scribble of his accusation, “but it would give me the greatest pleasure if you would learn the language of signs. You will find that after some practice its natural expressiveness makes communication a joy.”

Harmon picks up the paper to read it, then drops it back on the desk. His lips are in profile but I catch some muttered words. Of course, he says, followed by my mother’s name. Then a word that looks like Walnuts. I try to check myself, knowing that my thoughts are in a hopeless spin. Mr. Crane is in them, and this new fact of his relation to Mr. Bell. Has he told Mr. Bell everything? And there are no Walnuts on the table, no nuts of any kind in fact, and the table itself is fashioned of mahogany. Warned Us, I think. Not Walnuts. He is saying my mother Warned us. What did Mama warn us of? I try to stretch my mind back to her warnings, but all I can remember are her assurances and certainty.

He leaves the room and returns a moment later with a bundle of envelopes. Dread thickens through me. He is going to reveal Mr. Crane’s letters and show me the extent of my lie. But his lips bear a familiar request. Copy. I am to copy them.

I take the bundle, seeing that the handwriting is indeed his own. Of course, I say, unsure whether to be relieved.

I must go, he says, meaning the Department Store, but his eyes don’t move away from mine. He wants something more from me, but I don’t know what it is. Once he might have reached for me and all our missed words would have ceased to matter, the touch of our fingers draining them away like a straw empties a glass of water. Have a good day, I tell him, and he nods, but it’s a functional farewell, a mere agreement to part.

After he leaves, I look at the envelopes. There are six of them. At least we are back to usual business, although I don’t relish the prospect of more of his correspondence. I skim through the contents: potential customers, one school, nothing for Mr. Bell. But the last envelope is thunder in my eyes, bringing my heart right into my throat. This is Mrs. Ketter’s hand.

I tear it open, and her words spring up at me. The note is short on news but large in spirit. She never wrote long letters, although literacy was a blessing of her education at the Old Kent Road School. She will be in London next month, she writes, and is desiring to meet me. Could I come to St. Saviour’s? My happiness makes a small leap before I remember Harmon: I’ll have to go carefully, I think, hiding the letter away in my mother’s travel case.

After my mother’s death, Mrs. Ketter kept me grounded with housework. The house needed our attention. The months of sickness had let dust thicken on the sills and ledges. We set about with whitewash, soda and carbolic acid. We washed the lace curtains, folded away the carpets and scattered pails of wet sawdust over the floorboards. Mrs. Ketter went about on her knees with a pair of bellows, blowing cayenne pepper into the corners of every room. Some of it came back in our faces, making us sneeze and sputter and laugh. We stood in the yard, shaking and snapping the damp wool blankets until they were ready to hang. We talked from the start of every day to the end, and each task was a navigation of our tools and our signing, what to hold and how to do it, so you could keep up the conversation on one hand, if not two.

You’ll be mistress one day, Mrs. Ketter signed, signaling the house as we stood in the yard with the laundry. Mr. Holmwood’s health was not faring any better, and we were accustomed to weekly visits from his doctor. I looked at the house, its walls still dirty white from the cut-and-cover works, not even touched pink by the afternoon sun. I didn’t tell her what Mama had also said. “Your stepfather,” she had written, “promises that you’ll have Mrs. Ketter too.”

You’ll stay here with me? I replied.

She laughed. Leave this thundering house? No, never.

She meant the trains in the nearby tunnels. We felt the shuddering of brickwork and floorboards, as regular as clockwork, traveling up through our soles and into our shins. Mrs. Ketter and I became quite used to it, being in the house all day. I was even comforted by the vibrations. The trains had not stopped for Mama’s death and the house rumbled as it had always done. The house talked to us, from deep in the earth. Mrs. Ketter liked to muse on the travelers under our feet, and where they were going. She liked destinations. Her community was small and dispersed, so she was used to traveling long distances to see old friends. She taught me the sign for almost every British town and city. I learned Stoke and Bristol and Brighton in amongst Soap and Careful and Connect.

But Harmon’s eyes burned darkly whenever he found us signing. He couldn’t fail to notice how my smiles and replies came back faster for Mrs. Ketter’s signs than they did for his fingers and notebooks.

Mrs. Ketter even began to stop signing whenever he entered the room, and switched to finger-spelling instead. Sometimes she just curtailed our talk altogether, so that our terminated conversation swung like soft, heavy curtains into his face. He seemed to like that no better.

One day we were folding up the bed linen. It was one of those tasks for which no adaptation could be made to accommodate our conversation. We worked in stillness, feeling the sharp tugs traveling through the fabric as if it was threaded with nerves. Harmon came into the room and started finger-spelling at us. There was a heap of linen still to fold, but we stopped as he was clearly angry. There was some trouble with the household budgets. We were down on money, and the logs showed huge spendings at the market. What was Mrs. Ketter buying there?

I have logged everything, she insisted. It is all there.

Then you have been overcharged, he spelled. They have taken advantage of you and this has happened. He waved the account book to illustrate his point.

Mrs. Ketter protested on her fingers to Harmon, then in letters to Mr. Holmwood, who said Harmon ought to go directly to the market himself and take it up with the stall holders. But by that time Harmon had begun on other faults in her work, and by the following week she was gone.

For a while Harmon insisted on coming to the markets with me, although he hardly had the time. I watched as he talked and laughed with the stall holders. I waited for a better price to be presented to us. I didn’t know what had been achieved, as the price appeared the same, but Harmon was happy with it. I knew they hadn’t overcharged us. Mama had taught me how to spot the clear, cherry-red color of a fresh cut of beef. She told me what price to expect. It was in her letters. But he refused to heed me when I tried to show him. He said it wasn’t the point, but however I studied his lips, I couldn’t discern exactly what his point was. And then he found Miss Brindle to accompany me to the market, who seemed pleasant enough but never attempted any other conversation than the brisk ones she had with the stall holders.

I didn’t hear from Mrs. Ketter for months. Was she angry, or did Harmon keep her letters from me? As the date of her visit to London grows closer, I become agitated. How would Harmon know if I went? Mr. Holmwood asks no questions of me, and where I go in the daytimes.

Harmon brings me more letters to copy. The franchise is taking its first shaky steps. Invoices, letters, bills and receipts stack up on my desk. He has relented for the time being on writing to the schools for the deaf, so I don’t make any more blank copies for the drawer.

Letters arrive from Mr. Crane as well, but I put those in the fire. Anger singes me with each one. I should have suspected him when he told me he’d been able to get sight of the English patent. He was in the employ of Mr. Bell, not the Union. It is no mean feat to get hold of such a document.

Then news comes of Mabel’s baby. Harmon is almost as joyful as if the child was his own. I add a note of congratulations to his letter, but I can’t stop thinking of Mabel without her mother at her side, and only her housekeeper and husband to help her decipher the doctor’s words as the child is delivered. There is the child to be deciphered too, as it gets older and goes from crying to speaking. Harmon and I have never discussed children, and I try to push my own fears away with an image of Mabel, rosy-cheeked and smiling, the infant in her arms. But as I sign off Harmon’s letter, I can’t help remembering the empty, sunlit top floor of Oratory School, the to-and-fro of our notebook, and suddenly I long for Mabel’s confidence again.

“The child has no deformity,” Harmon writes in the short note he leaves at breakfast. “Mr. Bell rang a bell at her ears to check.”

No sooner have I spotted St. Saviour’s than I see Mrs. Ketter standing on the steps. She is chatting to another woman, her fingers flickering slowly with alphabet letters so I suppose her companion is new to the community and its language. I dawdle on the pavement, my mind casting back to my first weeks in London when she signed with me in this way too. Her close-lipped smile is broad and lopsided just like I remember it, and her silver curls bounce defiantly out from her bonnet. She waves both arms when she sees me. I break into a run, taking the steps two at a time and causing her companion to startle at my rapid, ungainly ascent. I fling my arms around Mrs. Ketter’s neck and feel her surprised laughter against my chest, her breath in my hair, the pats that come gently down on my back. I don’t want to let her go. In fact, I don’t for several minutes because my face is wet and her shawl smells like it always did, of primroses and salty-warm butter, and I can’t tell if the cotton is mopping up my tears or bringing them forth at the same time. So I cry into her shawl until she pries me from her neck and grasps my shoulders.

Careful! she signs, directing my gaze at a huge bag of oranges at her feet. I bought them just now from a costermonger girl. Turned out she was deaf! Came right up to me when she saw my signs. I bought all her oranges and told her to go to the Old Kent School and give the principal my name. This is Miss Burrows. New to the church. This is my dear friend, Miss Lark.

Miss Burrows has clearly found herself the recipient of Mrs. Ketter’s generosity in more ways than she was expecting, judging by the jut of her elbow over her bag which is stuffed with oranges. Her shoulder sags to one side under its weight as she watches Mrs. Ketter’s signs carefully. There is a hint of nervousness in her smile as she greets me and explains in finger-spelling that she was just leaving. Come again, I tell her, a broad mood of welcome suffusing through me which belies the fact I’ve only set foot in St. Saviour’s myself once. But the reunion with Mrs. Ketter has flooded me with a giddy abundance. You must come again, I insist.

Miss Burrows goes down the steps, the oranges making a sliver of color against her coat. Mrs. Ketter prods my arm. Here, help me with these.

Gathering up the oranges, I follow Mrs. Ketter into St. Saviour’s. This time the place is filled with people. A service must recently have been concluded, and the congregation stand chatting in the pews, hands in motion everywhere, or in circles that break and reform as people move between the groups. Mrs. Ketter takes my arm, leading me toward the door on the far side. It takes us ten minutes to reach the door, since she must pause every three steps to chat to someone and introduce me.

The room we eventually arrive in looks like the club room. It has been recently used, judging by the scattering of pens and crumbs on the tables. Mrs. Ketter goes to the centermost table, places the oranges in a bowl and starts unpacking a picnic of ham, salted silver side and bonbon crackers around it.

The service was good today, she signs. You hungry? I’ve been looking forward to seeing you for months. She pats the table. Sit down, sit down. Eat, eat. Tell me how you are.

Since there is already a damp patch in her shawl, I hardly dare answer truthfully, so I tell her what I can about my copy-work, and Mr. Holmwood and how he fares. I don’t mention Harmon and Mrs. Ketter doesn’t ask about him. Instead, she tells me about her four children and eight grandchildren, her new job as a housekeeper at a deaf school, and her husband, Arnold, who is plagued by an episode of gout. She details each of his balms and liniments and pills as we work our way through the picnic, grabbing mouthfuls between our signing, picking things up, putting them down, asking for clarifications, her anecdotes littered with my Rights and Whats?

Then she moves on to her newest grandchild who has been born hearing. Eleven deaf children in the family, she signs, and one is hearing. One! How is it possible?

Did you have the bell ringing? I ask, remembering Mabel, and Harmon’s letter about the Bells’ new child.

Oh yes, she signs. Everyone came, we had the biggest feast, the biggest party. You know what happened? The girl turned her head as soon as we rang the bell and nobody knew what to say to each other. A hearing child! The mother rang the bell three more times, from behind the door, the screen, even from outside of the room. Each time the baby turned, laughed. Laughing and laughing at the bell. Well, we all had to laugh too.

We pause our conversation to peel the oranges. The juice spreads across my tongue like sunshine. I watch Mrs. Ketter slipping the segments into her mouth, and wonder if she’s thinking about the costermonger girl, or her granddaughter, or both.

She wipes her hands on the flannels and with clean fingers spells a name. I have to get her to repeat it twice. Crane. Elbert Crane. Refusal rams through me. This is surely some kind of terrible mistake. Crane? I repeat.

Right, she replies. He wrote to me because you are not answering his letters.

She gives me a reproving look. I suppose my mouth is still open. I shut it. How do you know Mr. Crane? I ask but already I’m dreading her answer. The deaf community’s connections are tight and deep, and I don’t want to discover Mrs. Ketter and Mr. Crane knotted in the middle of them.

I’m a friend to his parents. But I didn’t meet Elbert until recently.

Recently? I repeat. When?

Last year. His grandparents took him away when he was a boy, so he grew up in London. He left for America when he was sixteen, and no one heard about him again. Then he decided to come back, and I met him finally.

For a moment I can’t think what to respond. This new fact of his history has re-configured him. Did they take him away because he was hearing? I ask.

She nods, and replies, They worried he wouldn’t learn English properly. His brother was deaf like his parents, so he was the only hearing one.

Three of them deaf? I ask.

Right, his grandparents thought they could leave the other child, that was fair and the best way. Elbert rarely saw his parents, she adds, and her index pops up in the air in a scattered fashion, for the occasional and infrequent visits. His signing is good now, isn’t it? He spends a lot of time at St. Saviour’s, but he must have remembered it from before.

His parents must have been happy, I sign, when he came back from America.

She shakes her head. They didn’t see him. It was too late. They had both died.

Died, died, she signs neatly, placing the two deaths side by side, and I feel my chest tighten. His brother? I ask. What about him?

He died when he was a child.

I watch Mrs. Ketter’s extended fingers sinking through the air for a third time, and I have to look away, picking at the piths of my orange instead. I try to hold on to the other truth, that Mr. Crane lied to me about his relation to Mr. Bell’s legal team, lest it become eclipsed by this new picture of his loneliness. You gave him my address, I sign, after a moment’s pause, but my signs are an abrupt burst nonetheless.

Mrs. Ketter doesn’t flinch, even at the fierceness of my pointing index. Elbert said he knew you from Boston, she replies. I was worried about you. I couldn’t visit, so I sent him instead.

The truth sharpens like needles at my temples. Elbert Crane sought out Mrs. Ketter to get to me, and she fell for it. I close my eyes until the thought subsides. Then I sign, He made no mention of you, shaking out my Nothing so hard that I feel the twinge in my right wrist from last night’s copying work.

Impatience jumps across Mrs. Ketter’s face. Yes, I understand that now. I don’t know what his game is, she replies. But I told him to sort things out. Now you won’t answer his letters so I had to come myself. She studies me for a moment. You’re worried. What’s the problem?

I take a breath. He bribed me, I tell her. He wanted me to spy on Mr. Bell. Because of Frank, I add. He said Frank owed him money and he wanted it back.

Mrs. Ketter nods, her eyes steadying on me so I feel their disquieting brightness. Her concern is not for what she’s missed, but for me. She used to look at me this way whenever Harmon said something that I couldn’t follow, or a visitor came to the house and Harmon forgot to explain who the person was, or why they were there. A new idea starts rising through me, creeping upwards like floodwater. Mr. Crane knew what happened in Philadelphia, and held me responsible.

Elbert’s a funny one, Mrs. Ketter signs. Shifty. I can’t get a sense of him. Too much mixing with hearing people, that’s my view. He can’t sort out a matter in a direct way. Crane isn’t even his name, or his grandparents’ name. That’s what happens, she finishes, when you live in two worlds but don’t belong in either. You end up with no idea of who you are.

He blames me, I blurt out. For what happened to Frank.

You blame yourself, she replies. That’s why you would never come to this place.

I feel so rigid with misery that the only escape seems to be a reassertion of the truth. Frank was in the penitentiary for one year, I tell her. He lost everything. His new job, his good name.

I wait but the bald statement of this fact appears to change nothing about it.

Mrs. Ketter reaches across the table and touches my hand briefly. Elbert made a mistake too, she signs. He shunned his parents, and then it was too late. I didn’t know he was going to lie like this. I’m disappointed, she decides. This is not the deaf way.

She starts rearranging the remaining oranges, stacking them into a bright pyramid, a centerpiece in the club room, so that everyone can help themselves. As I watch, Mr. Crane shuffles into my thoughts with an insistence that is a demand coming from himself; look at me, he’s saying, we are the same. What we have been denied. Our closest connections deemed harmful to us.

I tap the table for Mrs. Ketter’s attention. My mother went looking for you. I remember her making the trip. Afterwards she told me she had found a housekeeper. But I think she went to find you. She didn’t want anyone. She wanted a deaf person.

Mrs. Ketter smiles. Your mother came to this church for a recommendation. Yes, she was asking around. Then she visited me and said you needed some company. I was living in London back then, so I agreed.

Her shrug is quick and light, matching the simplicity of her explanation, but as her shoulders drop down again, the next part of the story seeps into the room like a slow exhale.

About Harmon, I begin, I don’t know what to do.

I wait, my breath trapped and tight, as she considers me. I want the certain, decisive strikes of her signs, but she makes them carefully. I agree with your mother’s decision for you. But you can always come to Bristol. It’s a long journey though.

As I watch her hand arcing westwards, I feel a deepening ache to open Mama’s last letter. Perhaps there’s no harm. After all, what is the point of advice, if it cannot be called upon when needed? But Mr. Crane must be dealt with first.

Tell Mr. Crane, I sign, to meet me at the Royal Society. Next Thursday evening.

There will be lots of rooms and people, I think. We can talk without drawing attention. But the thought of the speech I’ve volunteered myself for makes me feel cold all over, so I push it away.

Good! she signs. I’ll let him know. Her hand snatches at the air before her brow and swoops down and outwards: a transferring of knowledge from herself to Mr. Crane. It’s one of the first British signs she taught me—to let someone know—deftly showing how you slide the contents of one mind to another. And as she packs up our late luncheon, I notice the club room anew. The empty tables with their detritus are suggestive of the previous hour’s busy back-and-forth of conversation, seeded with facts, information, advice. The building is alive with knowledge, although no doubt Mr. Bell would prefer that it didn’t exist. This is how deaf people meet, make friendships, marry.

His face, shining in the lamplight on Washington Street, comes back to me. His advice about Frank, that he felt was so necessary, he was willing to put it on his own hands. The crispness of my understanding, finally; but it was an understanding I didn’t want. The refusal I’d felt at having to heed him rushes through me again, as fresh as the first time, even though I know it’s no use, and will change nothing about what happened.

Mrs. Ketter is watching me. Do you remember those newspapers you gave me from America? she asks. The silent press?

I nod, and she stands up, waving her hand, so I follow her across the club room to a second door, which opens onto a small library. Mrs. Ketter crosses to the shelves and starts running her eyes along the books, until she arrives at a section labeled in her own writing: North America.

On the shelf are all the papers that Frank gave me from his collection, which I’d never been able to return. She slides out a few and hands them to me. On the top, by chance, is the paper bearing the masthead Boston Silent Voice.

Frank’s paper. Wonder brushes through me as I hold the lightness of the pages. For a moment I feel I might look up and find the Washington letterpress and the huge type-cases around me again. Frank declaring there was room enough to dance in the print shop because from the shop you could reach deaf people in every corner of the world. A dance of connections yielding more connections, building into a movement and flow of links and fastenings, people coming together. I’d taken part in this dance myself by giving Mrs. Ketter the papers. And now Frank was touching me again with inked words and all the memories between them. I feel a soft drift of reverence that I can’t tell apart from hope, for how the past might be ordered and contained, and kept safe in a sacred place. I reach out and run my fingers down the spines and each one is like a tendon, taut and ready to dance.