3

Confidential

Two weeks after Mr. Bell’s visit, a third letter arrives from Mr. Crane. After I finish the morning tasks, I excuse myself from the house, taking the letter with me. My stepfather, Mr. Holmwood, lives in a backwater of Kensington, in a two-story terrace wedged between the huge villas with their adjoining mews houses, and the railway cut-and-cover, which is so close we all feel the regular rumbling of trains under our feet. Today I take the northerly streets directly to Hyde Park, avoiding the museums and the old grounds of the International Exhibition, where I used to walk. I’d no idea the Bells lived so close, although I’ve never once seen them there.

“Deceit and lies,” I read in Mr. Crane’s letter when I finally find a bench, “are only my line of business insofar as I seek to uncover them. If you do not think you can assist me with the outstanding debt I have described, perhaps you can advise as to where else I should make my inquiry. Is it your stepfather or fiancé to whom I should address myself?”

There’s no mention of Frank, but the ugly paragraph boils through me. I can’t have Mr. Crane go to either man with debts that I can’t easily explain. The envelope is still padded without the letter inside, so I upturn it, causing a handful of clippings to scatter into my skirts, with a note amongst them. It reads, “Consider, if you will, these claims about Mr. Bell. Minor charges, or would you disagree?”

Small items, carefully scissored from The Times. One article claims that Mr. Bell’s Telephone cannot be the subject of a patent because the telephone is actually fifty years old. Another letter names the true inventor as one Wheatstone who used wooden rods to conduct band music and later the ticking of a clock. A third writes of Faraday and another of Reis. All of them state that Mr. Bell’s device is little more than an improvement on what has gone before, and question his honesty in taking the credit.

I return the clippings to the envelope, feeling restless and exposed, as if Mr. Crane knew I’d read every one of them. I try to recall what I know of the inventors Wheatstone, Reis and Faraday. None of these men were on Mr. Bell’s lips or in his notebooks when he first told me what he dreamed about creating. My mind goes back to the schoolroom in Boston and the worry burning in Mr. Bell’s eyes. He was so tired, up all hours of the night. A night owl, everyone called him. He scarcely dared breathe a word of his idea to anyone else. Wouldn’t they just laugh at him?

To my alarm, I feel the tug of that old trust between us. None of these men, I’d like to answer The Times, had caused the human voice to flow along a wire. None of them had delivered conversations, declamations, singing. I flick through the articles again and other remembered words begin rising in me. Current, electrician, harmonic. Some of these words Mr. Bell had to write down, and occasionally he tore up the paper afterward.

Trousered legs and a pleated skirt appear next to my knees. I look up to find a perplexed couple. The gentleman is speaking, wagging his eyebrows and nodding his chin at the remaining space on the bench. I shift along to let them sit, realizing how my thoughts have strayed. I may have been Mr. Bell’s confidante once, but I wasn’t any longer, and didn’t wish to be one again.

I put the letter into my bag. The woman on the bench has turned to me and is saying something so I take out my notebook and show her the first page, which gives an account of myself. She reads Deaf-and-Dumb, and the alarm jumps in her neck and cheek, although she smiles when she wasn’t smiling before, her eyes uncertain. I turn to a clean page and offer her the pen, but she waves her hand—there’s no need, never mind—and shakes her head saying, Just the weather!

Is it just something about the weather? I wait but she bobs her smile and turns away. No matter, my thoughts are full of Mr. Crane, so I get up to leave. How am I to be rid of him? It’s no use writing another letter. I’ll need to meet him in person and explain the impossibility of the task. He must understand that this debt isn’t one I can ever repay, nor can Mr. Holmwood.

When I return to the house, Harmon is back unexpectedly for luncheon. Mr. Holmwood is waiting in the dining room, his white hair that I combed this morning already poking up in tufts. I’ll be one minute, I tell him, thinking of the food waiting under the domes in the kitchen. Our former housekeeper, Mrs. Ketter, was never late with a meal, although Mr. Holmwood isn’t one to chastise. He raises a hand: he rarely speaks these days, one side of his face given to immobility. To Harmon I spell: I was reading a letter from my grandmother.

Good, he replies, looking pleased since he could never understand the trouble Mama and I had with Adeline. He holds up an index finger. That reminds me, he says and wags his hand. Come, he means.

I half turn to Mr. Holmwood. But Harmon is saying Quickly and Won’t be long. Besides, my stepfather has drawn the daily papers toward him, and doesn’t seem hurried, so I follow Harmon to the study where yesterday evening’s copy-work has been left on the desk. Is he going to chide me for the mess? Copying provides a small income of which Harmon is ashamed, but I can fair copy two brief sheets an hour for a much lower fee than any clerk in this city. Harmon tells me that I won’t need to be copying for long. Once he’s promoted at the Department Store, I shan’t have to work again, although my skill with the pen and ledger may have some application for the store’s administrative affairs. He even promises to find a replacement for Mrs. Ketter, although he quibbles over the need while pretending money has nothing to do with it. His only arrangement has been the spinster down the street who comes daily to escort me to the market even though Mama taught me everything I needed to know, and Mrs. Ketter showed me how to go about it.

On top of my copy-work is a new pile of papers that I don’t recognize. Harmon points at them and spells, Business letters. I need you to make copies.

His fingers are crackling with the words, and his eyes have a bright bounce in them. I’ve seen the look before: an enterprising new idea has come to him. It is the same tendency that troubled his own father, Mr. Holmwood’s brother-in-law, who was a tradesman in china and glassware with a successful shop on New Bond Street. Before he died, he handed the reins to Harmon’s younger brother, insisting that Harmon lacked business acumen and was prone to flights of fancy. Angered, Harmon found a position in a Department Store on Oxford Street instead, but soon was dissatisfied. Then he wanted to organize a lecture series for a German man who claimed he was a world-leading mesmerist. Next it was setting up his own company to sell the latest gaslights. Neither came to fruition, and it was Mama who tried to reassure him. It was a good position, she said, and a man with his kind of energy would surely rise in it.

I try to think what Mama would tell him now, and make my advice like hers. I only manage: What about the clerks at the store?

His face is dismissive. He says something like, This isn’t about that, and waves a hand at my suggestion. He takes his notebook and begins to write, “Mr. Bell’s Telephone Company is renting out wires and instruments and I plan to establish the first Telephone franchise in this country.”

I stare at his words, and then at Harmon. He laughs a little and says, Don’t worry. He takes back the notebook. “The Telephone is a marvel,” he continues, “but now we must create its business uses.”

My hands jump up but I stop myself, switching to the pen instead. I try to match my words to his: strident, certain of themselves. “But surely,” I write, “businesses prefer a written record. Even the Post Office Superintendent thinks it cannot replace the telegraph.”

Harmon shakes his head, and his assessment arrives with me in fragmented paragraphs as the notebook goes back and forth. The Telephone provides speed and personal connection. Mr. Bell is a fine inventor and educator but not a businessman, whereas Harmon has turned around the fortunes of a Department Store. Well, that of his floor at least. Harmon will lease lines and instruments from Mr. Bell. He will bring on board shopkeepers and other department stores. “And we must think further afield,” he finishes. “Physicians will readily see the Telephone’s use for emergency calls. Pharmacies, lawyers. The list goes on.”

I take the pen from him. For a moment I think of pointing out that Mr. Bell has already surrounded himself with fine businessmen, Mabel’s father to start with. Instead I write, “I don’t think that the Post Office will allow private telephone companies. This isn’t the States.”

Harmon gazes as me, baffled by my resistance. I feel a skip of panic. How can I make him understand that I don’t want to renew my acquaintance with Mr. Bell? It is best to leave alone what can’t be undone. I try to forget how I rooted through Mr. Crane’s letter only a few hours ago, hoping for a mention of Frank.

“Unlikely,” he replies with matching tidiness, “as the Post Office does not have supremacy on this matter. Private companies are free to operate, so we must start immediately. I want copies of every letter that I send logged so I have it on record.”

I take up my fingers. I don’t have time, I tell him. When am I meant to do this? In the evenings I must finish my copy-work, then I sit with Mr. Holmwood.

The man is half-asleep by then, he replies. The evening is perfect. He winks so a dimple appears in one cheek, and says Yes? Hmm? with a nod that sends a wing of his auburn hair sliding forward. He picks up the letters and holds them between us like an offering but it only serves to end the conversation, his hands being too full of paper to reckon with any demur of mine. And once I take them, I won’t have my hands free to answer him either. This is a new tendency of his, to stop and start conversations as he sees fit. He closes a notebook when he decides he is finished, he turns away with a word still on his lips. Is it simply impatience, forgetfulness? I think back to our early days before Mama’s illness, and our long walks in Hyde Park together, talking all the time on our fingers. When he showed me around his floor at the Department Store, his fingers danced with letters as he relayed the queries of the shop-floor assistants and my replies to them. Soon he became my most regular interpreter. He sat beside me at lectures and social calls. He would spin other people’s speech and mine through this flicker of finger-letters. He didn’t mind the attention, the opposite in fact. Shy Harmon; I gave him new confidence.

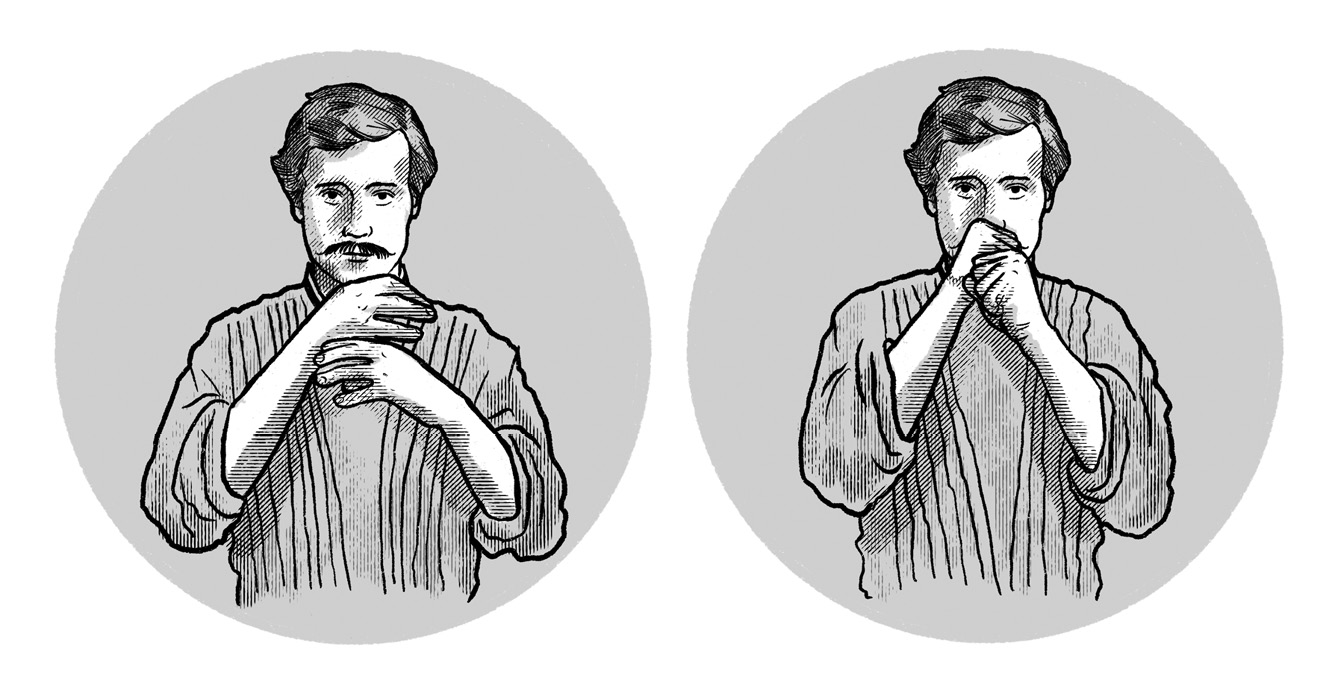

I take the papers and put them on the desk again. Then I spell emphatically, Problem, smacking the M into my palm. You don’t know how the Telephone works, I continue in a smooth stream, before lifting my palms and pressing the corners of my lips firmly downward. A what-to-do?, if not quite a rebuke.

Ah, wait. He’s raising an index and taking a card from his pocket. I feel a tremble in my arms as Mr. Bell’s writing comes into view. Then the card is in my hands, his sentences between my thumbs, as if I’m holding one of our class notebooks again. His scrawl is the same attempt at tidiness frustrated by his evident haste. It reads, “You are cordially invited to a DEMONSTRATION of the new TELEPHONE which shall be exhibited from the DEPTHS of THE THAMES.”

There follows a place and date: tomorrow.

I give back the card, hoping Harmon won’t notice that the tremble has reached my hand. How will it help? I spell. The Telephone will be in the river.

Harmon takes the notebook and writes, “Your speech, do you remember? I will write to all the schools for the deaf-and-dumb, and offer our services. Mr. Bell desires to do justice to Visible Speech in this country, but he has no time. We will help him, and he will return the favor.”

I keep my eyes on the page, not daring to lift my face in case he can see what is twisting inside me. I am a trading token. That is his plan. My Visible Speech for Mr. Bell’s Telephone. Mr. Bell already has my voice, I want to reply, inside the Telephone. Not just mine, but all his pupils. Hadn’t our voices plucked at the strings of Mr. Bell’s attention, enlivened his belief in the value of speech? He picked up a wire and dreamed a voice might travel inside it. He told me of it and bade me not to tell a soul. And I kept his promise, until I saw that it was already broken.

I agreed to one speech, I say, using my voice. It comes out roughly with my unused consonants, forgotten vowels. Then I write, “You want us to travel the country? We’re not even married.”

Harmon’s head nudges back. The dimple that appeared earlier seems sunk into his cheek. His face grows long, longer. There is a sharpening light in his gaze, an ugly look that sends my thoughts skittering. But then the blue of his eyes is calm again. I almost see the stumble as he catches himself and something firmer sets his face.

Kindness. Kindly. He is affecting sympathy. His finger-spelling becomes smooth again. I know you don’t want to speak, he spells. You know I have no problem with your voice. But you know Mr. Bell’s system, and this is what your mother would want for us. To advance ourselves. Mr. Bell’s friendship will help us.

He spells all the words except for the ones that denote the two of us. I and Us. You and Yours. Ourselves. For these, he taps his chest, slides an index between us, and jabs his finger toward me. Jab, jab. You, You, Yours. A shortcut, but it conveys his insistence.

My heart stalls on his mention of Mama. He hardly refers to her these days. Six months have passed since her death, and we acted as if it was better to let time quietly seal up my grief, and that of old Holmwood. Confusion spins through me, and I lapse into the question he wants me to ask myself: Would my mother tell me I should do this? In a drawer upstairs there’s a letter from Mama which I was sworn not to open until the eve of our wedding. It’s not the first time I’ve thought about it, but now my desire for her advice is stronger than ever. Mr. Crane, Frank, Harmon. They lean in, crowding around me, pointing me at Mr. Bell in different ways so I feel like a weathervane, and don’t know which direction to turn.

Fine, I reply, before I can stop myself. I consider snatching back the word, but I’m too stunned by what I’ve agreed to. A snappish all-right at Harmon; have I answered yes simply to his plans or yes to Mr. Crane as well?

Harmon smiles. Did I only imagine that brief ugliness of his anger? He flips both thumbs like a youngster, smiling now. Rich, is the word I see on his lips. Does he say that one day we will be rich, as will Mr. Bell?

After dinner I sit down with his letters, counting six. Three of them are to the principals of the schools in Bristol, Exeter and the Old Kent Road, London. One is for a physician acquaintance suggesting a Telephone wire between the man’s residence and his office so he can learn of emergencies more quickly. Another is addressed to the boss of his Department Store with a similar suggestion. The last is to Mr. Bell and requests the support of the Bell Telephone Company, and informs him of the schools he has contacted, offering us to demonstrate Visible Speech. Along with the letters there is also a new logbook. He wishes to record not only his business correspondence, but every favor we have granted Mr. Bell, in our arrangements with the schools. It’s a side of Harmon I try not to notice; his meticulous score-keeping.

I start on the copies but I can’t settle. A different kind of regret stings me all over and makes me feel afraid. Harmon used to send me letters regularly, and they weren’t like these ones. Instead he told me about his day and asked about mine. He slipped the envelopes under my door every night. The next morning, I propped my replies against the pepper mill at breakfast. He read them and laughed in all the right places, or so I guessed as I measured the way his eyes moved down the page. Mama smiled her appreciation from across the table. Sometimes he tucked them in his pocket, as he wished to reread them on his lunch break. That evening, there would be another letter filled with more anecdotes about the customers at the Department Store. “One lady,” he wrote, “came in with a ferret and I was certain it was a stole until it looked at me and squirmed.” Another letter: “I thought of you today when a gentleman asked for some earrings to match his wife’s eyes, and I realized that in all the department store we do not have any earrings that would do yours justice.”

After Mama died, the letters became fewer. I hardly noticed at the time, and Mama’s absence allowed him to move closer to me in other ways. With Mama gone, and old Holmwood unable to manage all of his affairs, Harmon was practically head of our small household. I was as good as his wife already. He still wrote notes of a practical nature, but they didn’t seem worth keeping.

And now I can’t bring myself to copy his business letters. My hand ghosting his words across the page will make me complicit in the things I don’t wish for, arrangements I want no part of. Instead, I open the logbook and enter the details of the business letters before sealing them into envelopes. I leave them ready for posting, with no copies made.

The next day, rain is drifting across the Thames Embankment. A crowd of twenty-odd gentlemen is assembled behind the railings while farther back onlookers pause in the street, drawn to the sight of Mr. Bell. He stands by the river, dressed in a diving suit and waving a gloved hand next to the vast copper dome on his head. Breathing tubes are looped to the helmet’s side. A ladder is secured to the railings where a second diver is lowering tubes into the water, readying Mr. Bell’s descent. His boots look so heavy I wonder how he can even lift his feet. A pale smudge of nose hovers behind the window of his helmet. Of his lips, there’s nothing to see. I look around for Mabel although in her condition, in this weather, she’s surely keeping indoors.

Between the shuffle of brollies and shoulders is the Telephone. An assistant is giving a talk, but I only catch the words: Voice and From the Depths. A wire connects Mr. Bell’s butterstamp handle to a black wooden board, then trails across the table, over the railings and into the water, running parallel to Mr. Bell’s breathing tube. The tube is fat like an intestine, whereas the wire is as thin as hair. They will make an exchange: air will go into the river, and his voice will come out of it. Mr. Bell will be vanished, and yet there will be the sound of him, like some ghostly essence.

As I watch him waving his hand uncertainly in the vast helmet and suit, Mr. Crane’s request seems absurd. Even if I should see enough of Mr. Bell’s words, what is he likely to reveal here? Every public occasion is a demonstration or explanation: not a confession. His job is to promote the Telephone, to represent the fruits of his labor. He won’t be telling them how business isn’t treating him kindly. That the Germans are making telephones more cheaply on the continent, and another company has secured the German patent. He won’t mention the other patents he’s losing in Europe, and how soon the continent will be flooded with cheap telephones not owned by him. Not a word about the debate in The Times or the Western Union and their legal case. His patents taken from him, his name teetering at the edge of history, his chance of a fortune washed away with it. His reputation hangs in the balance but he will smile and smooth his troubles away as he explains his invention in a manner that will stoke nothing but fascination. In short, nothing of use for Mr. Crane.

Now Mr. Bell is astride the ladder, ready to enter the water. The canopy of umbrellas is broken apart by waving arms and hands. Mouths open with well-wishing cheers. Slowly Mr. Bell descends until he’s gone from sight. A few people rush to the railings and peer after him, before turning to the crowd and confirming that he is indeed underwater.

Everyone clusters around the Telephone. I half expect riverweed and rusted nails to come out with his voice. The crowd is restless, chattering to each other as the assistant passes around the butterstamp handle, each person hoping to be the first to hear Mr. Bell’s voice.

When it reaches me, I slide a finger into the small hole in the receiver’s base. Hope quivers across my shoulders. How would Mr. Bell’s voice feel? A tingle, a shiver, a tremble? To my surprise, I want the Telephone to know me, to curl Mr. Bell’s words into my palm, like a child placing its hand in its parent’s. I make myself as still as possible, waiting for the Telephone to recognize my touch.

But there’s nothing. I pass on the receiver, ignoring the odd looks from the assistant and the crowd. Harmon clasps my hand against the folds of our coats. I suppose I must look crestfallen.

The gentleman who has the butterstamp receiver raises his palm. His eyes narrow as he pushes the receiver against his ear. Yes. Yes! It’s Mr. Bell’s voice.

There is laughter and commotion. Everyone wants a turn with the Telephone. I watch Harmon take his. A song, I see him say, but his face strains at the earpiece. Perhaps the water has swirled Mr. Bell’s speech into a broken, burbling melody. He has become part-merman, blowing bubbles into the ears of this distinguished crowd, teasing them. But they mask their disappointment: it is a marvel all the same.

You are probably right, I spell, ignoring the interest of the assistant at my finger-flicker. He might have a piano down there.

Harmon smiles. Then Mr. Bell heaves himself up the ladder, water streaming off his suit. His assistants help him over the railings. Together they lever off his helmet, and he stands blinking in the rain.

Headache, I see him say. I have the most awful headache.

His words sail so easily into me that I’m jolted with surprise. I can’t help glancing around the crowd. Did anyone understand him? But he’s still some distance off, waving at his audience as the assistants remove his diving suit. The cheer from the crowd hums across my shoulders. Since I ought to look like I too am celebrating, I knock my palms together with them, while watching Mr. Bell closely. Here he is, at another successful demonstration, smiling at his admirers, and yet he’s unhappy, even unwell. And no one in the crowd has a clue. I can’t help feeling victory’s snap of pleasure. For a moment, I’ve more sense of him than anyone else here, however their ears may serve them.

Headache, he says and rubs at his temples.

I turn to Harmon and take out my notebook. I don’t want Mr. Bell to see our finger-spelling, since he surely knows the British alphabet from his early years in Scotland. He was teaching even back then. “He has a bad headache,” I write as gray spots of rain appear on the page. Harmon frowns, concerned.

“It must be the water pressure,” he writes back.

Liberated from his diving suit, Mr. Bell enters the crowd to receive praise and questions. His face is pale. Harmon takes my elbow and tries to ease us through the throng, but every time he finds a gap someone steps between us and we have to wait. Peeved, he asks, What else is he saying?

I try to watch Mr. Bell but the gentlemen surround him, and I’ve only an interrupted view of his face. I write, “He is telling them how much rubbish there is in the Thames.”

Harmon shakes his head with as much disgust as if I’d told him drowned babies were down there among the riverweed. Terrible, he says. Quite terrible. What else? he spells.

But Mr. Bell has spotted us. He says Excuse me to the gentlemen and comes over before I can answer.

What did you think? he asks, and adds You, Finally and See.

We have finally seen the Telephone. His head is turned toward me, as he makes his words clear. I feel relief to understand him. Half of it, I say, and Mr. Bell laughs.

It was very dark down there, he replies. I saw nothing! I feel quite awful.

You should take a rest, I say, but he waves away my suggestion. Rest, he says. No. And adds something about how little time there is. I can’t help smiling, and he notices. What? he asks. Ah, I always say that.

He smiles and the swerve feels dangerous, even though Mr. Bell looks pleased. I’m almost thankful when Harmon starts talking. A letter, he says, so I guess that his topic is business. At first he glances at me while he talks, trying to stitch me into the conversation with the needle-like dips of his eyes. But soon he has forgotten himself, his lips are too quick and he stops looking at me at all. I watch for mention of a Telephone Franchise. Surely he is smoothing the conversation in that direction. Isn’t that why we are here?

And Mr. Bell is listening to Harmon. He nods, smiles, nods again attentively. Certainly they make a motley pair, with Mr. Bell expanding into comfortable statesmanship, while Harmon looks like he fuels on nothing but water and the agitation of his thoughts. Harmon isn’t a calm influence by nature, but his manner is clever and deferential, and he’s generous with his admiration. People of a certain type like having him around, and I now see that Mr. Bell is one of them.

I feel restlessness pawing at me like an animal. How long will they talk for? Harmon doesn’t look like he’s stopping anytime soon, and neither does the drizzle. I shift on my feet, trying to adjust my posture as I feign interest, make some nods, smile at what appear to be timely moments. I’m practiced at this. I mustn’t burden Harmon with my incomprehension and task him with fixing it. But still I can’t help my boredom.

Mr. Crane’s proposal drifts into my mind. I had understood Mr. Bell better than I’d hoped, even when no one else did. Headache, Mr. Bell had said. I feel awful, he’d told us, as if here amongst everyone we alone were his confidants. Perhaps even in this crowd Mr. Bell will break from his spiel of promotion. Could I bring something to Mr. Crane that would be enough to satisfy him? A new thought has troubled me lately. What if Frank simply could not pay the debt himself after what happened between us?

Then I see Mr. Bell say Headache again. Harmon says, You must try not to think of it, and Mr. Bell is saying Health and Nervous Excitement. His health, he is saying, followed by Skin. Is there some trouble with his skin?

He waves an index at the river and tells Harmon the doctor didn’t recommend it. A salt bath, a spa town, not a filthy river.

They laugh, and Harmon is asking him: Why?

Mr. Gray.

That’s the answer I see on Mr. Bell’s lips. The reason for his poor nerves, his health and his skin is Mr. Gray. He says Mr. Gray several times and looks quite troubled.

Elisha Gray. One of the inventors from the Western Union’s stable. It can’t be. I blink it away. Mr. Bell discussing in idle chat his rival Mr. Elisha Gray as the cause of his headaches? I know I’ve made a mistake. The shape lingers in my thoughts as doubt spirals around me. What other words look like Mr. Gray? I used to play lip-reading games with Mama where you had to tell certain words apart using your wits alone. Paper, baby. Egg, ache. They looked the same on the lips so what mattered was how they were framed. But most words have no match, no twin, however hard you try to find one. My eyes strain as I watch for more words, this time on Harmon’s lips.

Mystery, Harmon is saying. That surely makes more sense for two people who don’t know each other so very well. The cause of Mr. Bell’s bad health is a mystery.

I wait as the words tumble between the two men. Mystery, Mr. Gray. Then the conversation moves on, leaving me with a memory, as fragile as a scent, of their shapes. The words are almost similar. What if I didn’t make a mistake at all? Mama always said to trust your first instinct, and there is nothing to lead me astray, like the jar of peaches when Mr. Bell first visited us. There is no reason that I should think of Mr. Gray, unless it was what Mr. Bell said.

My mind skips to Mr. Crane. I can’t help composing an answer to him in my head. “If you would agree to meet,” I’ll write, “I should like to discuss in person the matter of your proposal. I have already gathered some information, but first I need good reason why you should be worthy of it.”

Frank. He’s the only good reason. I can’t bear the thought of his debt, which is becoming more like mine as each day passes. I seal up Mr. Crane’s letter in my thoughts, thinking it’s just a fancy, of course I shan’t be sending such a letter, but when I turn back to the men, Harmon is talking about the letters he has written to the principals of the schools, and the speech I will give to them, and the anthropologists. He is saying my name, that I have written many pages.

Mr. Bell looks at me and I feel the rain’s chill go through me for the first time that evening.

Well, something short, he says. His thoughts have worked creases around his eyes.

He doesn’t trust me after all, I think.

I take out my notebook, feeling in need of its safety. “We are so happy we could come today,” I write, and present the notebook so that he is forced to drop his gaze to the page.

Yes, he says, and then Harmon is saying Goodbye and Mr. Bell is saying the same. Before we turn away, he catches my elbow. The touch surprises me: a habit he has with deaf people, but it burns like a brush with a candle flame. Harmon’s eyes skip down and up, but any judgment is forestalled by Mr. Bell’s next remark. You must call on us, he says. My wife would be thrilled.

Oh, I say, forgetting the notebook. Thank you. Thank you, I repeat because Mr. Bell isn’t smiling, instead he’s watching me closely, as if he’s reaching for something in my face. I square my shoulders and present myself openly to his search, but I can’t help the tightness that traverses through me, finding an outlet in my grip on the notebook.

He starts speaking carefully. My wife can offer advice, he says, on your wedding. Setting up home. It must be difficult without any womanly advice. She misses her own family greatly, he adds.

I try to unhook my stare from his face without much success. Did I see his words correctly? Surely, he remembers this isn’t the first time he has sought to give me advice on my marriage?

A shadow of anxiety passes through Mr. Bell’s brow and jawline. He is waiting, I realize, for my answer. The reference to my mother’s absence feels like a knife pressed against the balloon of my resolve. He didn’t give his condolences, I realize, on his first call, or were they among all the other words I missed? Something inside me starts to tear. I think of pointing out that we shall not be setting up home on par with the residence they have in Kensington, but instead I take up my notebook and put down my finest hand. “Please thank Mrs. Bell,” I write. “I am much in need of advice.”