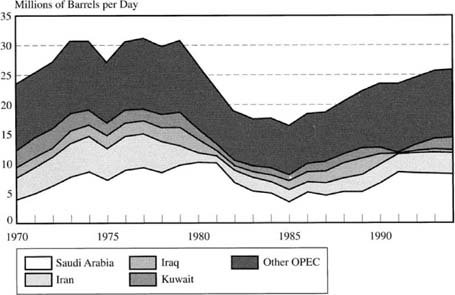

Figure 9-1 Production of Crude Petroleum by OPEC Countries in Millions of Barrels per Day, 1970–1994

The most successful effort of Southern countries to alter their dependent relationship with the North was the common action of OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) in seizing control over the world's oil markets. By acting together in a producer cartel, the Southern oil-exporting states were able to increase not only their economic rewards but also their political power. OPEC's success led to efforts to form other Southern commodity cartels. But the OPEC model would prove difficult to reproduce, and even OPEC eventually confronted the inevitable limitations of a producer cartel.

For most of the twentieth century, the international oil system was controlled by a producer cartel. Until 1973, that cartel consisted of an oligopoly of international oil companies.1 The “seven sisters”—five American (Standard Oil of New Jersey, now known as Exxon; Standard Oil of California, now known as Chevron; Gulf, now part of Chevron; Mobil; and Texaco), one British (British Petroleum), and one Anglo-Dutch (Royal Dutch-Shell)—first gained control of their domestic oil industries through vertical integration—that is, by controlling all supply, transportation, refining, marketing operations, as well as exploration and refining technologies.

In the late nineteenth century, the oil companies then in existence began to move abroad and obtain control of foreign supplies on extremely favorable terms.2 After World War I, the seven formed joint ventures to explore foreign oil fields, and eventually in the 1920s they began to divide up sources of supply by explicit agreements. They were thus able to divide markets, fix world prices, and discriminate against outsiders.3 Northern political dominance of the oil-producing regions—the Middle East, Indonesia, and Latin America—facilitated the activities of the oil companies. Governments provided a favorable political and military environment and actively supported the oil companies owned by their nationals.

In bargaining with the oil companies, the less-developed countries were confronted by an oil oligopoly supported by powerful Northern governments as well as by uncertainty about the success of oil exploration and the availability of alternative sources of supply. It is not surprising that the seven sisters obtained concession agreements that gave them control over the production and sale of much of the world's oil in return for the payment of a small fixed royalty to their host governments.4

Beginning in the late 1920s and continuing through the Great Depression, oil prices tumbled despite the efforts of the seven sisters to stabilize markets. At that time, the United States was the largest producer in the world and exported oil to Europe and elsewhere. Efforts at the government level (including not only the U.S. federal government but more significantly the largest producer state, Texas) succeeded where the seven sisters could not in regulating production in order to create a price floor. Thus, the Texas Railroad Commission emerged as the single most significant political force in the international oil industry.

Changes in this system began to emerge in the decade following World War II. In the 1950s, relatively inexpensive imported oil became the primary source of energy for the developed world. Western Europe and Japan, with no oil supplies of their own, became significant importers of oil. In 1950, U.S. oil consumption outdistanced its vast domestic production, and the United States became a net importer of oil. In the host countries, growing nationalism combined with the great success of oil exploration led to dissatisfaction with concession agreements and to more aggressive policies. In these years, the host governments succeeded in revising concession agreements negotiated before the war. They redefined the basis for royalty payments and instituted an income tax on foreign oil operations. They also established what at the time was considered a revolutionary principle: the new royalties and taxes combined would yield a fifty-fifty division of profits between the companies and their respective host governments.5 As a result, profits accruing to host governments increased significantly. The per-barrel payment to Saudi Arabia, for example, rose from $0.17 in 1946 to $0.80 in 1956–1957.6

Nonetheless, the seven sisters, also known as the majors, continued to dominate the system. By controlling almost all the world's oil reserves outside the Communist states (e.g., production at the wellhead, refining and transportation, and marketing), they were able to manage the price of oil.

The seven sisters maintained control, in part, by preventing incursions by competitors. The majors blocked other companies from entering upstream operations such as crude oil exploration and production outside North America by locking in concession agreements with many oil-rich areas and by the long lead times required for finding and developing oil in territory unclaimed by the majors. Outsiders were also deterred from competing with the seven sisters downstream—that is, in refining, transportation, and marketing operations. Not having their own crude oil supplies, independent refiners had to purchase oil from the majors, who were also their competitors. But the majors deliberately took their profits at the less-competitive and lower-taxed upstream level by charging a highprice for crude oil as compared with the final product. The small profits for downstream operations discouraged new entrants.

The management of the price of oil was facilitated by the highly inelastic demand for oil. Because there are no readily available substitutes and because it is difficult to decrease consumption, an increase in the price does not greatly decrease the demand for oil in the short run. Thus, if companies can maintain a higher price for oil, they will not lose sales volumes and so will reap high profits.

Thus, in the 1950s and 1960s, the seven sisters controlled supply by keeping out competitors and by a series of cooperative ventures: joint production and refining arrangements, long-term purchase and supply agreements, joint ownership of pipelines, and some joint marketing outside the United States. They also refrained from price competition. Price management by the majors was designed to keep the price of oil economically attractive but also low enough to discourage competing forms of energy, including nuclear energy. Developed country governments did not resist this price management. Europeans added a tax on petroleum in order to protect the domestic coal industry, because lower oil prices would have increased oil consumption at the expense of the politically powerful coal companies and coal miners. In the United States, higher oil prices were supported by the domestic oil industry that needed protection from lower international prices to survive and, as we shall discuss, eventually obtained that protection.7

Finally, the dominance of the seven sisters was backed by political intervention. One extreme example occurred in the early 1950s when the government of Iran sought a new agreement with the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, a predecessor of British Petroleum, and nationalized the company's assets in Iran. The British government became actively involved in the negotiations, imposed an economic embargo on Iran, and threatened military intervention. After trying unsuccessfully to mediate between Britain and Iran, the United States worked with opposition parties and the shah to overthrow the Iranian government. A new concession was soon negotiated under which the U.S. companies replaced Anglo-Iranian.8

However, as OPEC would later discover, it is difficult to maintain a producer cartel in the long run. Over time, changes in the international oil industry, the oil-producing states, and the oil-consuming developed countries undermined the dominance of the seven sisters.9 The oligopolistic structure of the international oil industry was weakened by the entrance of new players. Competition increased both upstream, as new players sought concessions to explore for and produce crude oil, and downstream, as more refineries were built and competition grew in markets for refined oil. Starting in the mid-1950s, companies previously not active internationally obtained and successfully developed concessions in existing and new oil-producing regions such as Algeria, Libya, and Nigeria. In 1952, the seven majors produced 90 percent of crude oil outside North America and the Communist countries, and by 1968 they still produced 75 percent.10

As new production by new producers came on line, the seven sisters were no longer able to restrict supply and maintain the price of oil at the old level. By the end of the 1950s, production increases outdistanced the growth in consumption. United States quotas on the import of foreign oil aggravated the problem. Quotas were instituted in 1958 ostensibly for national security reasons: to protect the U.S. market from lower-priced foreign oil in order to ensure domestic production and national self-sufficiency. In fact, quotas also helped domestic U.S. producers that could not have survived without protection.11 The quotas effectively cut off the U.S. market for the absorption of the new supplies produced abroad. As a result, in 1959 and 1960, the international oil companies lowered the posted price of oil, the official price used to calculate taxes. This act was to be a key catalyst for producer-government action against the oil companies.

Changes in the oil-producing states also weakened the power of the oil company cartel. In addition to changing elite attitudes, improved skills, and less uncertainty, the emergence of new competitors was critically important in increasing the bargaining power of the host governments. In negotiations with the oil companies, producer states obtained larger percentages of earnings and provisions for relinquishing unexploited parts of concessions.12 As a result, the oil-producing governments, especially large producers such as Libya and Saudi Arabia, increased their earnings and began to accumulate significant foreign exchange reserves. Monetary reserves further strengthened the hand of the oil producers by enabling them to absorb any short-term loss of earnings from an embargo or production reduction designed to increase the price of oil or to obtain other concessions.

At the same time, host governments began to cooperate with each other. Infuriated by the price cuts of 1959 and 1960 that reduced their tax receipts, five of the major petroleum-exporting countries—Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela—met in 1960 to discuss unilateral action by the oil companies. At that meeting, the five decided to form an Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries to protect the price of oil and the revenues of their governments.13 In its first decade, OPEC expanded from five to thirteen members, accounting for 85 percent of the world's oil exports.14 Initially, the new organization had little success. OPEC s influence depended on the ability of its members to cooperate to reduce production and thus to force a price increase. Although OPEC tried, it was unable to agree on production reduction schemes. Nevertheless, the individual oil-producing states succeeded in increasing their revenues. The posted price of oil was never again lowered. And the oil-producing states gradually expanded their experience in cooperation. But not until the 1970s, when other conditions became favorable, would OPEC become an effective tool of the producer states.15

Finally, the Western consuming countries became vulnerable to the threat of supply interruption or reduction. As oil became the primary source of energy and as U.S. supplies diminished, the developed-market economies became increasingly dependent on foreign oil, especially from the Middle East and North Africa. By 1972, Western Europe derived almost 60 percent of its energy from oil, almost all of which was imported. Oil from abroad supplied 73 percent of Japan's energy needs. And 46 percent of U.S. energy came from oil, almost one-third of which was imported. By 1972, 80 percent of Western European and Japanese oil imports came from the Middle East and North Africa. By 1972, even the United States relied on the Middle East and North Africa for 15 percent of its oil imports.16 This economic vulnerability was accentuated by declining political influence in the oil-producing regions and by the absence of individual or joint energy policies to counter any manipulation of supply.

In the 1970s, OPEC took advantage of these changes and asserted its power as a producer cartel. Favorable international economic and political conditions plus internal cooperation enabled the oil-producing states—especially the Arab oil producers—to take control of prices and, then, to assume ownership of oil investments.

The OPEC revolution was triggered by Libya,17 a country that had definite negotiating advantages: it supplied 25 percent of Western Europe's oil imports;18 certain independent oil companies relied heavily on Libyan oil and were more vulnerable than the majors in Libya; and Libya had large officiai foreign exchange reserves. After Colonel Muammar al-Qaddafi seized power in 1969, the new radical government demanded an increase in the posted price of and the tax on Libyan oil. When the talks with the companies stalled in 1970, the government threatened nationalization and a cut in oil production. It targeted the vulnerable Occidental Petroleum, which relied totally on Libya to supply its European markets. Shortly after production cuts were imposed, Occidental, having failed to gain the support of the majors, capitulated, and the other companies were forced to follow. The settlement provided for an increase in the posted price of and the income tax on Libyan oil. The Libyan action revealed the vulnerability of the independent oil companies like Occidental and the unwillingness of the Western governments or the majors to take forceful action in their support.

At a meeting in December 1970, OPEC called for an increase in the posted price of and income taxes on oil. The companies, seeking to avoid a producer policy of divide and conquer, agreed to negotiate with all oil-producing countries for a long-term agreement on price and tax increases. The governments of the oil-consuming states, although increasingly concerned, allowed the companies to manage relations with the oil producers.19 Following threats to enact changes unilaterally and to cut off oil to the companies in February 1971, the companies signed a five-year agreement that provided for an increase in the posted price of Persian Gulf oil from $1.80 to $2.29 per barrel, an annual increase in the price to offset inflation, and an increase in government royalties and taxes. In return, the companies received a five-year “commitment” on price and government revenues. In April 1971, a similar agreement, but with a higher price, was reached with Libya. After the devaluation of the dollar in 1971 and 1972 and thus of the real price of oil, the producers demanded and received a new agreement that provided for an increase in the posted price of oil and continuing adjustment to account for exchange rate changes. The price of Persian Gulf oil rose to $2.48.

No sooner had the issue of price and revenue been settled than OPEC requested a new conference to discuss nationalization—that is, control over production. A December 1972 agreement among Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Abu Dhabi, and the companies provided a framework: government ownership would start at 25 percent and rise gradually to 51 percent by 1982. Individual states then entered into negotiations with the oil concessionaires.

The final negotiation between the oil producers and the oil companies took place in October 1973. Despite their successes, the oil producers were dissatisfied. Although surging demand for oil drove up the market price, the posted price remained fixed by the five-year agreements. Thus, the oil companies, not the oil producers, benefited. Furthermore, the companies were bidding for new government-owned oil at prices above those of the five-year agreements.

Finally, increasing inflation in the West and continuing devaluation of the dollar lowered the real value of earnings from oil production. Economic conditions were favorable to OPEC. Because of rapidly rising demand and shortages of supply, the developed market economies were vulnerable to supply interruption. Thus, when OPEC summoned the oil companies for negotiations, they came. Negotiations began on October 8. The oil producers demanded substantial increases in the price of oil; the companies stalled; and on October 12 the companies requested a two-week adjournment of talks to consult with their home governments.

The adjournment was not for two weeks but forever. Political as well as economic conditions now enhanced the bargaining position and escalated the demands of the most powerful oil producers: the Arab states. The fourth Arab-Israeli war had begun on October 6, just two days before the oil talks began. A common interest in supporting the Arab cause vis-á-vis Israel and the supporters of Israel in the consuming states was a force for unity of the Arab members of OPEC in their economic confrontation with the companies and the consumers. On October 16, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) unilaterally increased the price of their crude oil to $5.12.20 Other oil producers followed. On December 23, OPEC unilaterally raised the price of Persian Gulf oil to $11.65.

After the autumn of 1973, oil prices were controlled by OPEC. Operating in a market where supplies were limited and demand high, the producers negotiated among themselves to determine the posted price of oil and the production reductions needed to limit supply and maintain price. The key to reducing supply was the role of the major reserve countries and large producers. Saudi Arabia and Kuwait were willing to support the cartel by themselves, absorbing a large part of the production reductions necessary to maintain the price. The role of these two countries was facilitated by the tight oil markets, which meant that price could be managed when necessary by only limited production reductions. Power over price was quickly translated into equity control. All the major oil-producing states signed agreements with the oil companies for immediate majority or total national ownership of subsidiaries located in those states. In the long run, as we shall see, the abrupt movement of control over production from the seven sisters to OPEC would prove to be the real revolution of the 1970s oil crisis.

The monopoly control of oil by OPEC, the unity of the producers, and tight market conditions undermined the position of the oil companies. Furthermore, the companies had little incentive to resist. They were able in most cases to pass the price increases along to consumers and thus did not suffer financially from the loss of control over price. Although no longer either the arbiters of supply and price or the owners of oil concessions, the seven sisters and their many smaller relatives still played a vital role in the international oil scene. As holders of technology and markets, they were needed by the newly powerful producer governments. As their holdings were nationalized, they became vital service contractors to the producer states. Still, it was a far cry from the days when the companies divided up the producing regions among themselves and obtained control of the world's oil for almost nothing.

With the decline of the companies, the Northern consumer governments tried but failed to agree on a common policy toward the producers. The United States urged Western Europe and Japan to form a countercartel that would undermine producer solidarity by presenting a united front and by threatening economic or military retaliation. The Europeans and Japanese—more dependent on foreign sources of oil, less interested in support for Israel, and somewhat fearful of U.S. dominance—instead advised cooperation with the producers. A consumer conference in early 1974 failed to reconcile these opposing views. The only agreement was to establish an International Energy Agency (IEA) to develop an emergency oil-sharing scheme and a long-term program for the development of alternative forms of energy. France, the strongest opponent of the U.S. approach, refused to join the IEA and urged instead a producer-consumer dialogue.

After the conference, consumer governments went their own ways. The United States tried to destroy producer unity by continuing to press for consumer unity and the development of the IEA. The Europeans sought special bilateral political and economic arrangements with the oil producers and resisted consumer bloc strategies. In late 1974, a compromise was reached between the United States and France. The United States obtained France's grudging acceptance of the IEA, although France still refused to join, and France obtained the grudging support of the United States for a producer-consumer dialogue. The Conference on International Economic Cooperation (CIEC), begun in 1975 (see Chapter 7), constituted a recognition, if not a total acceptance, by the United States and the other consumers that they could not alter the power of the producer states over the price of oil and that what they could seek at best was some conciliation and coordination of common interests. Even that coordination provedelusive. In 1977, the CIEC and the effort to achieve a forum for a producerconsumer dialogue failed.

For five years the management of the international oil system was carried out by OPEC under the leadership of Saudi Arabia. Saudi dominance of OPEC s production and Saudi financial strength enabled that country to manage the oil cartel virtually singlehandedly. Saudi Arabia accounted for close to one-third of OPEC's production and exports, controlled the largest productive capacity and the world's largest reserves of petroleum, and possessed vast financial reserves (see Figure 9-1).

In periods of excess supply, as during the recession of 1975, Saudi Arabia maintained the OPEC price by absorbing a large share of the necessary production reductions. The burden of such reductions was minimal because of the country's huge financial reserves and because even its ambitious economic development and military needs could be more than satisfied at a lower level of oil exports. In periods of tight supply, Saudi Arabia increased its production to prevent

Figure 9-1 Production of Crude Petroleum by OPEC Countries in Millions of Barrels per Day, 1970–1994

SOURCE: Department of Energy, Energy Information Agency, via the World Wide Web at http://www.eia.doe.gov.

excessive price rises. With a small population, limited possibilities of industrial development, and the world's largest oil reserves, Saudi Arabia's future is dependent on oil. Furthermore, with its financial reserves invested largely in the developed countries, it has a stake in the stability of the international economic system.

Thus, although the Saudis want a price of oil that is high in terms of Saudi Arabia's cost of production (less than $1 per barrel), they do not want a price high enough to jeopardize the future of an oil-based energy system and the viability of the world economy. The Saudi view is shared by other Gulf states who, with the Saudis, form the moderate camp in OPEC.

The Saudis were willing and able to threaten or actually to raise production to prevent the price increases desired by other OPEC members favoring a more hawkish strategy on oil prices. These countries, which traditionally have included Iran, Iraq, Venezuela, and Nigeria, have large populations, ambitious development plans, and smaller reserves and, therefore, they seek to maximize their oil revenues in the short term. For example, in 1975, OPEC, over Saudi opposition, approved an immediate 10-percent and subsequent 15-percent price increase. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) split with the other OPEC members, announced a 5-percent increase, and greater production. By June, they had forced the rest of OPEC to limit the price increase to an acceptable 10 percent. In 1978, when oil markets eased, the Saudis maintained the price by absorbing the majority of reductions of production, exports, and earnings. And in 1979 and 1980, when supplies became tight once again, the Saudis increased production to try to prevent a price explosion.

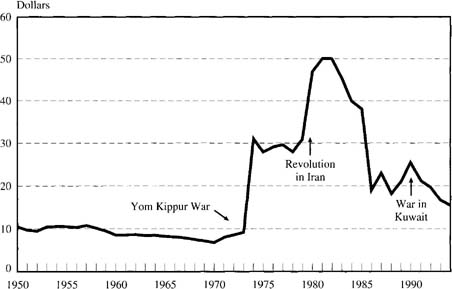

In addition to Saudi policy, a propitious environment contributed to the stability of the international oil system. In the mid-1970s, recession in the OECD countries, combined with conservation efforts arising from the increase in price, led to a stabilization of demand for oil (see Figure 9-2). Indeed, demand for crude oil was about the same in 1992 as it was in 1973. At the same time, the supply of oil was steady and even growing. OPEC production as determined by the Saudis was steady: There were no serious efforts to constrict the supply in order to push up the price. And new sources of oil—from the North Sea, Alaska, Mexico—were coming on line (see Figure 9-3).

Political conditions in both the producing and the consuming states also enhanced stability. OPEC states, pursuing ambitious economic development programs, were spending their earnings at a rapid rate. Between 1974 and 1978, their combined current-account surpluses actually declined, from $35.0 billion to $5.2 billion.21 As a result, the oil states had an interest in maintaining production, and therefore earnings, at a high level. In addition, key OPEC states friendly to the West, in particular Saudi Arabia and Iran, were responsive to Western concerns about the dangers of economic disruption from irresponsible management of the price and supply of oil.

The Western countries remained divided and acquiescent and, as time went on, increasingly complacent. Their inability to carry out a major restructuring of energy consumption rapidly was not cause for alarm, because the system seemed

*Exajoules = 1018 joules. (A joule is unit of measurement of energy equivalent to I watt of power, occurring for 1 second. The joule is approximately equivalent to 1/4 caloric or .001 BTU (British thermal unit). There are 3.6 million joules in a kilowatt hour).

Note: Includes biomass, the burning of wood, charcoal and other biologically based fuels for energy.

SOURCE: British Petroleum, BP Statistical Review of World Energy (London: 1993) and electronic database (London: 1992), and Worldwatch estimates contained in Worldwatch Institute, Worldwatch Database Diskette 1995 (Washington: Worldwatch Institute, 1995).

Figure 9-3 OPEC and Non-OPEC Oil Production in Millions of Barrels per Day, 1970–1994

SOURCE: Department of Energy, Energy Information Agency, via the World Wide Web at http://www.eia.doe.gov.

to have stabilized at an acceptable level of price and supply. Furthermore, Western foreign policies—the U.S. policy of developing and relying on special relations with Saudi Arabia and Iran, and the European and Japanese policies of general political support for the oil producers—seemed to promise security of supply and stability of price. The Saudi rulers, safe on their throne, friendly to the United States (except on Arab-Israeli issues), and cognizant of their new responsibilities to the world economy, seemed to have OPEC well in hand. The government of the shah of Iran, also apparently stable and reliable, was more hawkish on price than the Saudis but more reliable on supply because it was not directly involved in the Arab-Israeli dispute.

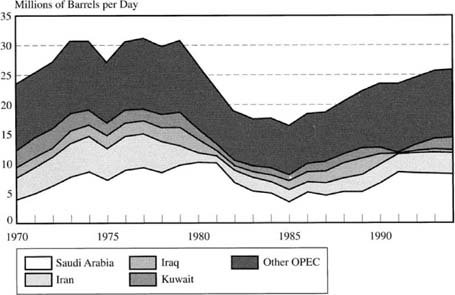

As a result of the effective and moderate Saudi management and a propitious environment, supplies were adequate, and after the beginning of 1974, the price of oil in real terms actually dropped, as the periodic price increases by OPEC were offset by inflation (see Figure 9-4).

By 1978, however, the political and economic environment had become highly unstable, and the ability and willingness of the Saudis to manage the price

Figure 9-4 Real Price of Oil, 1950–1993, in Constant 1993 Dollars per Barrel

SOURCES: British Petroleum, BP Statistical Review of World Energy (London: 1993) and electronic database (London: 1992); Worldwatch estimates based on ibid., and on Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration, Monthly Energy Review February 1994 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1994).

and to ensure the supply of oil had diminished. By the end of the 1970s, the demand for oil imports increased as Western economies moved out of the 1974–1975 recession, as the initial shock effect of the price rise wore off, and as complacency set in with the real decline in the price of oil. While demand increased, the world's supply of oil fell. Iran had sharply curtailed its production. Saudi Arabia was willing to increase its production in the short run, but it kept output below capacity and suggested that it would not increase production ceilings in the future. And Kuwait announced plans to decrease its production.

By the end of 1978, the international oil system was once again vulnerable to disruption. World oil supplies were only barely adequate; any slight decrease in supply or increase in demand would precipitate a world shortage and put serious upward pressure on prices. If a supply reduction or demand increase were small, Saudi Arabia might be able to fill the gap and stabilize the system. But if the shifts were large, even the Saudis might not be able to control the system.

The event that created a world shortage of oil and disorder in world oil markets was the 1978 revolution in Iran. At the beginning of 1978, Iran exported 5.4 million barrels of oil a day, about 17 percent of total OPEC exports. At the end of 1978, as part of a successful effort to depose the shah, oil workers cut off all oil exports from that country. By the spring of 1979, the loss of Iranian oil had been to a great extent offset by increased production in the other oil-producing states. Saudi Arabia, for example, increased its production from about 8.3 million barrels per day in 1978 to about 9.5 million barrels in 1979.22 However, the effect on oil markets of the loss of Iranian oil could not be completely offset. The crisis led not only to a shortage of supply during the latter part of 1978 and early part of 1979 but also to a greater demand for oil, as consumers tried to augment stocks to protect against anticipated future shortfalls in supply. The result of this perceived shortage and rapid scrambling for stocks was again escalating prices and turbulence in the world oil markets.

The first signal of that turbulence came at the December 1978 OPEC meeting. At that time, OPEC agreed to gradually implement price increases amounting to an effective increase of 10 percent for 1979, a rate above the expected Western inflation rates and therefore the first real increase in the price of oil in five years.

This new price, however, did not hold. The Iranian revolution set off panic in the spot market for oil, which spilled over into the long-term contract markets. Most crude oil was then sold by long-term contract between the oil-producing countries and the oil companies at a price determined by OPEC. Oil not under long-term contract was sold in spot markets where the price fluctuates according to market conditions. In 1978 and 1979, those conditions were very tight, creating severe upward pressure on the spot market prices. In early 1979, spot prices rose as much as $8.00 above the OPEC price of $13.34 for Saudi Arabian light crude, their chief traded oil. The differential between the OPEC price under long-term contract and the higher spot price benefited the oil companies, which were able to purchase contract oil at relatively low prices. Many OPEC members, unwilling to allow the companies to benefit from such a situation, put surcharges above the agreed OPEC price on long-term contract oil and even broke long-term contracts in order to sell their oil on the spot markets. Despite its production increases and its refusal to add surcharges, Saudi Arabia was unable by itself to restore order to the world oil markets.

In March 1979, OPEC confirmed that the system was out of control. Instead of gradually implementing the price increase agreed in December 1978, OPEC announced it would immediately implement a 14.5 percent increase. More importantly, OPEC decided that its members would be free to impose surcharges on their oil. The surcharges, which many members immediately instituted, demonstrated that even OPEC and the Saudis were unable to control the price of oil. Furthermore, the OPEC members sought to maintain the tight market, which favored price increases, by agreeing to decrease their production as Iran returned to the oil export market. Despite an agreement by International Energy Agency members to reduce oil consumption by 5 percent for 1979, there was little consumers could do in the short run to stabilize the system. In July 1979, OPEC raised the price again. As the oil minister of Saudi Arabia explained, the world was on the verge of a “free for all” in the international oil system.23

By the middle of 1980, the free-for-all appeared to be coming to an end. High levels of Saudi production and stable world consumption led to an easing of markets. In this climate, Saudi Arabia and other OPEC moderates sought to regain control over prices, reunify price levels, and develop a long-term OPEC strategy for gradual, steady price increases geared to inflation, exchange rate changes, and growth in the developed countries. In September 1980, OPEC discussed the long-term strategy and planned to continue deliberations at a summit meeting of heads of state in November 1980.

But the plan was destroyed by the outbreak of war between Iraq and Iran. On September 22, 1980, Iraq launched an attack on Iran's oil-producing region, and Iran's air force in turn attacked Iraq's oil facilities. The result was a halt in oil exports from these two countries and a reduction in world supplies by an estimated 3.5 million barrels per day—roughly 10 percent of world oil exports. The war dashed all hopes for stability in world oil markets. The OPEC summit was postponed indefinitely, and pressure began to build in the spot market. In December 1980, OPEC members set a new ceiling price of $33 a barrel and spot prices reached $41 a barrel.

The loss of Iraqi and Iranian oil was offset by a high level of world oil stocks, increased production by other Gulf states of an estimated 1 to 1.5 million barrels per day, and the sluggish demand caused by recession and the efforts of members of the International Energy Agency to dissuade companies from entering the spot market in precautionary panic buying, as they had done in 1979. Although such factors prevented panic and chaos, pressure on the spot prices was inevitable, as those countries that had relied on Iraq for oil imports turned to the spot market. As the hostilities continued, spot-market prices gradually rose, thus putting further pressure on long-term prices. Furthermore, damage to the oil production and export facilities in both countries raised questions about oil supplies even after the cessation of hostilities.

As the market conditions disintegrated, the foreign policies of the West, particularly that of the United States, were substantially weakened. The special relationship of the United States with Iran under the shah became one of hostility under the new Islamic government. Even the relationship of the United States with Saudi Arabia seemed threatened. The Camp David agreement between Israel and Egypt had led to a cooling of Saudi-U.S. relations. For the Saudis, the overthrow of the shah, the inability of the United States to keep him in power or even to prevent the holding of U.S. hostages raised doubts about the value and reliability of U.S. support. The events in Iran and an internal insurrection in Mecca in 1980 also raised the specter of internal political instability for both Saudi Arabia and the United States, which Tehran was seeking to foster.

Unstable market conditions and political uncertainty gave rise to widespread pessimistic predictions about the stability of oil prices and the availability of oil in the future. At the height of the second oil shock, experts predicted continuing chronic shortages and periodic interruptions in the supply of oil, at least through the end of the century, by which time alternative energy sources would supposedly be more fully developed. It was also predicted that OPEC market management would keep the price of oil rising approximately 2 percent faster than the rate of inflation.24 Few observers of the international oil situation in the late 1970s foresaw the profound changes that were to take place as the world moved into the 1980s, changes that not only undermined the ability of the oil oligopoly to manage the price of oil but also threatened the very institutional survival of the OPEC cartel.

OPEC's problems in the 1980s stemmed from its success. The cartel's ability to increase the price of oil eventually transformed the world oil market. The demand for oil fell, non-OPEC production grew, and as a result, a long-term surplus emerged, putting sustained downward pressure on prices. Moreover, the excess supply made it more difficult, if not impossible, for OPEC to manage prices, as it had in the previous decade.

The transformation of the international oil scene was due, in part, to declining demand. Total oil consumption in the industrial countries fell by an estimated 10 percent between 1980 and 1984, after having risen almost continuously for decades.25 Worldwide recession and slow rates of growth in the major consuming countries contributed substantially to this decline. There was also a structural change in consumption patterns. Price increases led to a greater substitution of other fuels for oil, especially in the developed market countries, which rapidly expanded their consumption of coal, natural gas, and, in some countries, nuclear energy. Higher oil prices also stimulated energy conservation and structural adjustment, which were reinforced by government regulations and incentives. Price controls had cushioned the U.S. economy from the effects of the oil-price increases, encouraging imports and discouraging domestic exploration. The removal of controls precipitated a reduction in imports and permanently altered the structure of demand in the United States.26 In response to the high oil prices, energy efficiency increased. Automobiles became more fuel efficient and homes were better insulated. It is estimated that industry in the noncommunist developed countries improved its energy efficiency by a massive 31.1 percent between 1973 and 1982.27

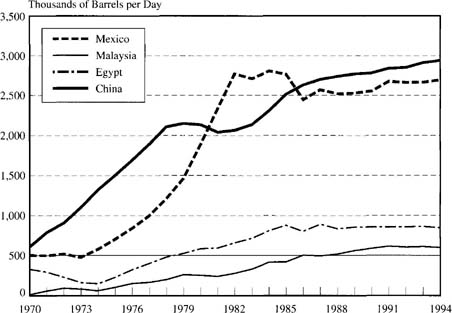

Along with the fall in demand, higher oil prices also attracted new suppliers to the international market. OPEC's management task became considerably more difficult, as the OPEC countries lost a substantial portion of their share of world production to non-OPEC producers. OPEC's share of the world oil market fell from 63 percent in 1973 to 48 percent in 1979 to 33 percent in 1983 (see again Figure 9-3).28 Non-OPEC production in the oil-exporting developing countries—especially Mexico and, to a lesser extent, China, Egypt, and Malaysia—rose steadily, from 2.8 million barrels per day in 1973 to 7.5 million barrels per day in 1983 (see Figure 9-5). In the developed countries, several large reservoirs of new

Figure 9-5 Oil Production in China, Egypt, Malaysia, and Mexico in Thousands of Barrels per Day, 1970–1994

SOURCE: Department of Energy, Energy Information Agency, via the World Wide Web at http://www.eia.doe.gov.

SOURCE: Department of Energy, Energy Information Agency, via the World Wide Web at http://www.eia.doe.gov.

oil came into full operation, most notably in the North Sea, which made Norway and Britain players in the international oil game (see Figure 9-6). In addition, the former Soviet Union increased its production and exports in order to boost its foreign exchange earnings (see Figure 9-7).29

Meanwhile, higher energy prices stimulated increased domestic oil production in the industrialized importing countries. Higher prices and price decontrol in the United States promoted greater investment in the petroleum sector and encouraged new oil companies to enter the market, exploring for new crude sources as well as developing new purchase and distribution lines.30 As a result of conservation, adjustment, and increased domestic production, the noncommunist developed countries reduced their total demand for imported oil by 40 percent, decreasing their reliance on foreign oil from two-thirds of total consumption in 1979 to less than half in 1983.31

Trends in the developing countries were different from the experience of the developed countries. Oil consumption in the developing countries as a whole expanded by approximately 7 percent a year from 1973 to 1979, attributable to relatively high rates of economic growth, generally low domestic oil prices, a lack of oil substitutes, and a limited capacity for conservation. After the second oil shock, however, oil consumption in the developing world rose much more slowly, with most of the increase in consumption attributable to the net oil-exporting countries.32 A few oil-importing developing countries were able to expand their

SOURCE: Department of Energy, Energy Information Agency, via the World Wide Web at http://www.eia.doe.gov.

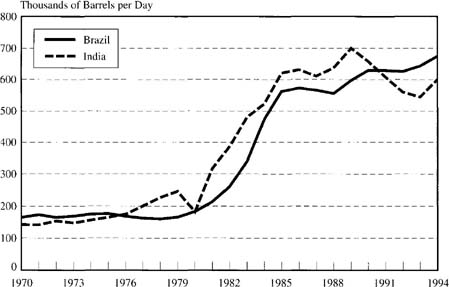

domestic oil production. Brazil increased its production by 50 percent between 1973 and 1983, and India raised its output fivefold (see Figure 9-8).

Downward pressure on oil prices from the sharp drop in demand and the rise in non-OPEC production was exacerbated by an unprecedented drawdown of oil inventories by the international oil companies. Companies had built up their reserve stocks to their highest levels ever during the uncertainties of the 1979–1980 oil shock. Lower oil prices, high interest rates that raised the cost of holding inventories, and, most important, the growing realization that the sluggish world demand for oil was the result of long-term changes in demand patterns and not merely a cyclical phenomenon led to a massive reduction in inventories.33

Shifting supply and demand depressed oil prices. On the spot market, prices fell from $40 per barrel in 1980 to $30 per barrel at the end of 1982, further lowering long-term contract prices.34 As a result, the GNP of the OPEC countries as a whole fell every year during this period. Although Saudi Arabia and some of the high-income OPEC countries were able to maintain positive trade balances, the current-account surpluses of many OPEC members disappeared, constraining their development plans, imports, and, for heavily indebted countries like Nigeria and Venezuela, payment of debt-service obligations.35 The fall in demand imposed a particularly heavy burden on Saudi Arabia, which, in its informal role as OPEC's market manager, was forced to reduce its production drastically, from a peak of 9.9 million barrels per day in 1980 to less than 5 million barreis per day by 1983, in order to defend OPEC's prices. Saudi oil revenues fell from a peak of $102 billion in 1981 to $37 billion in 1983. The Gulf countries also reduced their production in support of the Saudi price stabilization effort. As a result, Kuwait's oil revenues fell from a 1980 peak of $19 billion to $9.8 billion in 1983, and the United Arab Emirates oil revenue declined from $18 billion to $11 billion during the same period.36

The changing pattern of oil production and consumption increased OPEC's management problems and undermined the cartel's cohesion. As we have seen, the factors that set the stage for OPEC's success in the 1970s had changed by the 1980s. Whereas the demand for oil had been inelastic in the 1970s, conservation and interfuel substitution increased elasticity by the 1980s. Whereas the oil supply seemed inelastic in the 1970s, by the 1980s, new sources had diminished much of the cartel's original advantage as the main source of the world's oil. New non-OPEC suppliers also made the cartel's management more difficult. Finally, as the tight supply eased and prices fell, political differences within the cartel further undermined OPEC's capacity for joint action. Excess supply gave rise to enormous strains within OPEC, and the hardship exacerbated traditional conflicts between those OPEC members seeking to maximize their short-term revenues in order to boost imports and hasten development plans and those like Saudi Arabia

Figure 9-8 Oil Production in Brazil and India in Thousands of Barrels per Day, 1970–1994

SOURCE: Department of Energy, Energy Information Agency, via the World Wide Web at http://www.eia.doe.gov.

and the Gulf states wanting to maintain foreign dependence on OPEC oil for as long as possible by limiting the price increases.

Eventually, OPEC became a victim of the classic cartel problem: cheating. The first episode of cheating occurred between 1981 and 1983. In 1981, several OPEC members—in particular Algeria, Iran, Libya, Venezuela, and Nigeria—undercut the cartel's price-management system by producing over their prescribed ceiling, offering price discounts, and indirectly cutting prices through extended credit terms, barter deals, and the absorption of freight costs by the seller. As long as Saudi Arabia was willing to shore up prices by restraining its own production, these countries were able to violate OPEC's rules without creating a collapse of prices. The Saudis, however, became more and more bitter about having to sacrifice in the face of rampant cheating by their fellow cartel members. Not only were they losing foreign exchange earnings, they were also facing reduced supplies of natural gas that is produced in conjunction with oil and on which the Saudi economy had become dependent.

The expanded volume of oil traded on the spot market after 1978 made it more difficult for OPEC to monitor its members' oil transactions and thus aggravated OPEC's price-management problem. With new non-OPEC sources of supply, greater availability of cheaper oil from OPEC cheaters, slackened demand, and less fear of rising prices, the oil companies saw less need for long-term contracts and more often met their supply needs through the spot market. Whereas in 1973 over 95 percent of all oil was traded on long-term contracts, by 1983 at least 20 percent of the world's oil was traded on the spot market.37

The situation was aggravated by continuing disputes over national production allocations within OPEC. Iran, in particular, pressed to maintain or increase its market share at the expense of Saudi Arabia. The Gulf states were reluctant to agree to any production quota unless there was some agreement to end price discounting. Several cartel meetings failed to produce any consensus for dealing with the rampant cheating.

By early 1983, Algeria, Libya, Iran, and Nigeria were selling oil as much as $4 below the $34 OPEC price. Increasingly impatient, Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies threatened to lower their prices to undercut the cheaters. The threat of a price war was serious. A price collapse would have had severe effects on growth, development plans, military expenditures, and domestic political stability in virtually all of the OPEC member countries. For indebted oil exporters like Mexico, Venezuela, Nigeria, and Indonesia—and their creditor banks—a sharp drop in prices could have precipitated bankruptcy and a worldwide financial crisis. Other exporters like the United Kingdom, Norway, and the Soviet Union would also suffer from a price fall, as would the oil and banking industries in the United States.

In January 1983, an emergency OPEC meeting collapsed because of the running feud over the distribution of the quotas and price discounting. The international oil markets reacted almost immediately. Spot market prices fell, oil companies began depleting their inventories, and producers came under increasing pressure to reduce their long-term contract prices. The Soviet Union reduced its prices, as did the smaller non-OPEC producers like Egypt. More significantly, the British and Norwegian oil companies proposed to reduce the price of North Sea oil. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf producers continued to threaten to cut their prices if some agreement were not concluded.

Finally, in March 1983, OPEC members hammered out an agreement that signaled major changes in the oil-management system. For the first time in the cartel's history, OPEC reduced the price of oil, from $34 per barrel to $29 per barrel. To maintain this price, the members agreed for the first time to a concerted production reduction scheme that limited OPEC output to 17.5 million barrels per day and allocated production among the members. Saudi Arabia formally accepted the role of “swing producer” and committed to adjust its output to support the newly agreed-upon price.38

The new production reduction scheme slowed but did not stop the long-term decline in OPEC's power as a price-setting cartel. Sluggish demand and increasing production by countries outside OPEC continued to put downward pressure on oil prices. Domestic economic problems and financial shortages tempted members to break ranks by reducing prices and expanding production to obtain more revenues. As non-OPEC production grew and as non-OPEC producers such as Norway and the United Kingdom lowered prices below that of OPEC, it became more and more difficult for the cartel to reach agreement on production ceilings and quotas among members. In 1984, OPEC lowered the price to $28 per barrel, reduced its production ceiling to 16 million barrels per day, and lowered individual production quotas. Despite OPEC's production allocation scheme, virtually all of the decline in output was absorbed by Saudi Arabia. While other OPEC members either maintained or increased their output, Saudi production declined dramatically. By August 1985, Saudi output had fallen to 2.5 million barrels per day, less than one-fourth of its production in 1980–1981.39 Saudi foreign exchange earnings suffered a steep decline and the drop in oil production once again impinged on domestic requirements for natural gas.

In the second half of 1985, Saudi Arabia abandoned the role of swing producer. In order to increase its production and restore its market share, Saudi Arabia abandoned selling crude oil on the basis of official OPEC prices and instituted “netback” sales contracts—a market-responsive price formula based on the value of products into which its oil was refined. Once this happened, OPEC was no longer able to manage the price of oil. In December 1985, OPEC recognized the inevitable. It abandoned the system of fixed official selling prices and concerted production reductions. For the first time since the seven sisters agreed to set prices, the oil cartel agreed to allow prices to be determined by the market.

Largely due to the dramatic increase in Saudi production, OPEC output soared by almost one-third in 1986. The result was volatility and a sharp fall in the price of oil. Spot-market prices fell from between $27 to $31 per barrel in November 1985 to between $8 to $10 per barrel in July 1986.40 The collapse of oil prices led to a parallel drop in the value of oil exports to their lowest level since 1973.

Pressure to restore concerted production reductions and higher prices built both within and outside OPEC. In mid-1986, OPEC agreed to interim production reductions and quotas. Then, in December, the cartel reached agreement on new production reductions and quotas and on a new fixed export price of $ 18 per barrel. Supply control was helped by a slight decline in non-OPEC production due both to voluntary production restraint by non-OPEC exporters and to the shutdown of some high-cost production, especially in the United States. As a result, spot market prices rose to $17 to $19 per barrel in 1987.41 Once again, the cartel pulled back from a price war and reestablished market discipline and prices, albeit at a lower level.

Nonetheless, economic and political conflicts continued to threaten OPEC's ability to implement concerted production reductions. The traditional split remained between hawks like Iran and Iraq, which sought to maximize oil earnings in the short term, and moderates like Saudi Arabia and the Gulf countries, which sought to maximize oil earnings over the long-term. This conflict was complicated by an internal civil war over quota allocations. Although a number of OPEC members felt their quota allocations were unfair, the cartel was hopelessly divided and unable to revise the existing agreement. Thus, a number of members resumed cheating by producing over their quotas. The key was the United Arab Emirates, a Gulf state that has a small population and no pressing revenue needs and that thus should have fallen in the camp of the moderates. However, the UAE believed its quota was unfair and in 1988 began pumping twice its allocation. As concerted supply restraint weakened, prices of oil slipped downward.

Another important problem grew out of the Iran-Iraq war. It was a sign of the change in the oil markets that the bombing of oil tankers and shipping facilities in the Persian Gulf did not lead to a run-up in oil prices during the 1980s. The spare capacity of the other OPEC and non-OPEC oil producers, public stocks in consuming countries, as well as the oil-sharing arrangement of the International Energy Agency cushioned any potential threat.

It was the end of the Iran-Iraq war that posed a threat to oil prices. During the war, Iraqi demands for an increase in its quota met implacable resistance from Iran, which insisted on maintaining its second place in OPEC quotas (behind Saudi Arabia) and refused to allow its enemy to improve its relative position. Resolution of the conflict was deferred during the war by leaving Iraq out of the allocation scheme. As long as the war limited the ability of both Iran and Iraq to pump oil, the Iraq-Iran conflict did not threaten OPEC's supply management. However, the cease-fire between the two agreed in mid-1988 posed a serious threat to OPEC's ability to control oil supplies. Iraq was in the process of significantly expanding its production capacity. Both countries faced higher revenue needs for rebuilding and resuming economic development after the lengthy war, and both felt justified in producing more because of postwar needs and because of their reduced production during the war. However, because of the mutual distrust and antagonism arising from the war, OPEC was initially unable to negotiate a new allocation scheme.

At this point, Saudi Arabia intervened. Faced with cheating by the UAE, new demands by Iran and Iraq, and the seemingly intractable Iran-Iraq stalemate, Saudi Arabia followed the strategy that it had pursued before. It increased production in an effort to force other OPEC members to resume discipline. OPEC output rose from an estimated 18.5 million barrels per day to an estimated 22.5 million barrels per day. The glut of Saudi oil led to a fall in oil prices to $13 to $14 per barrel by late 1988. In real terms, oil prices were below the 1974 level. The decline in prices hurt the finances of all oil exporters; put severe pressure on indebted oil exporters such as Nigeria, Mexico, and Venezuela; and contributed to political instability in Algeria. By November, action by Saudi Arabia and Kuwait had forced OPEC to agree on a new production agreement to limit production to 18.5 million barrels per day and raise prices to $18 per barrel. Iran received its old share allocation and agreed to allow Iraq to return to the OPEC system with a quota equal to its own. Iraq's increase came at the expense of other cartel members, especially Saudi Arabia, whose quotas were decreased. The question was whether the agreement would hold and for how long, especially if and when the export capacity of both Iran and Iraq increased substantially.

The events of the 1980s thus led to a major change in OPEC's power as a price-setting cartel. Sluggish demand, sustained oversupply, competition from outsiders, economic temptations to break ranks by reducing prices and increasing production, and internal political conflicts undermined the role of the oil-producing cartel. Saudi Arabia could offset some cheating by other members but was no longer willing or able to single-handedly manage the cartel by playing the role of the swing producer.

In the absence of OPEC discipline, some cartel members protected themselves from price competition by buying refining and marketing operations in the major oil-consuming countries. During the 1980s, a number of OPEC members—Venezuela, Libya, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—acquired downstream operations in the United States and Western Europe. Moving downstream was intended to protect crude oil exporters when prices fall, because it guaranteed an outlet for oil and because prices for refined products fell less than prices for crude oil. As these OPEC members developed refining and marketing capacity, their oil operations came to resemble the large, integrated oil companies that once dominated the oil system (see Figure 9-9). They found themselves in even greater conflict with other OPEC members that remained dependent on crude oil exports for revenues and sought therefore to maximize oil earnings in the short term. The downstream diversification strategy, therefore, further weakened OPEC.

SOURCE: United Nations, World Economic and Social Survey 1994 (New York: UN, 1994), 143.

Differences among OPEC members over the price of oil and production quotas necessary to manage the price were a major factor in the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq in August 1990. Concern about the consequences of that invasion for world oil markets was a central reason for the strong reaction of the United States, Saudi Arabia, and their allies. In 1989 and 1990, Iraq and Kuwait were on opposite sides of a significant conflict within OPEC. Iraq emerged from its war with Iran facing severe limits on its ability to produce and export oil. Huge debts made it impossible for Iraq to borrow funds to rebuild its oil production and export facilities. These constraints combined with its desperate financial situation led Iraq to advocate a policy of maintaining high prices within OPEC through greater member discipline. Kuwait took the opposite position. With a large production capacity of 2.5 million barrels per day and large reserves of 100 billion barrels, Kuwait, like Saudi Arabia, advocated lower prices as a way of discouraging production by alternative suppliers of petroleum and investment in alternative energy sources. Because Kuwait was not as influential within OPEC as Saudi Arabia, it did not feel as much responsibility for maintaining the organization's effectiveness.

Thus, Kuwait refused to go along with the production quota assigned to it by OPEC in the late 1980s of 1.15 million barrels per day. Cheating by Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates was addressed at an OPEC meeting in November 1989. At this meeting, Kuwait's quota was increased to 1.5 million barrels per day and the UAE was exempted from abiding by its quota. The new agreement did not hold, however, and oil prices declined from $20 per barrel in January to $17.75 per barrel in March 1990. In May, OPEC held an emergency meeting in an effort to decrease total production and increase prices. Saudi Arabia agreed to lower its production, pushing up the price by about $1 per barrel, but, according to Iraq, Kuwait refused to comply with OPEC limits. In the ensuing months, oil prices continued to fall to under $17 per barrel. Iraq claimed with increasing vehemence that Kuwait was deliberately undermining the Iraqi economy by overproducing, and that it was, in addition, siphoning oil from a disputed field on the border of the two countries. President Saddam Hussein began massing troops along the Iraqi-Kuwaiti border. A last ditch effort by OPEC to resolve the dispute collapsed in July, and on August 2 Iraq invaded Kuwait.42

The Iraqi invasion led to a spike in the price of oil to nearly $40 per barrel by October 1990. The invasion also led to a swift reaction by both producers and consumers of oil. The United States led the formation of a broad international coalition that included Saudi Arabia, numerous Middle Eastern countries, France, and the United Kingdom. In October 1990, the coalition supported a U.N. resolution authorizing an embargo that would close all world oil markets to Iraqi exports. This embargo affected a flow of 4.3 million barrels per day of oil to world markets, about 7 percent of the world total. U.N. action combined with increased production by both OPEC and non-OPEC producers helped to reduce the impact of this very effective embargo on the rest of the world. In addition, the oil consuming members of the International Energy Agency released their strategic oil reserves in order to cushion the impact of U.N. embargo on world oil markets.43 The coalition then sent military forces to the region and, on January 16, 1991, launched a military action that liberated Kuwait and led to a record one-day drop in oil prices. The allies did not succeed in toppling Saddam Hussein, however.

While numerous factors motivated the United States and its allies in reacting strongly to the invasion of Kuwait, concern about oil was one of the most important. Control of Kuwait would have put Iraq in a position to dominate the weakened OPEC. Control over Kuwait's petroleum reserves would have given Iraq control over a total of 200 billion barrels, about one-fifth of the world total of known commercial oil reserves. Combined Iraqi and Kuwaiti daily production capacity would have been around 5.5 million barrels per day, still below that of Saudi Arabia (8.5 million barrels per day) but large enough to give the Iraqi government significant market power. Furthermore, with control of strategic military positions in Kuwait and with its large army, Iraq would have been able to threaten other key oil producers in the region, including Saudi Arabia. Such dominance of world oil markets by a single country was unacceptable to both consumers and producers of petroleum and helped to explain the unique alliance that formed against Saddam Hussein. Following the war, due to Iraq's continuing ability to manufacture weapons of mass destruction and its refusal to agree to effective monitoring of its activities, the U.N. maintained sanctions on all exports to Iraq except for food and medical supplies and other humanitarian needs. The U.N. also maintained its embargo on exports of Iraqi oil.

The Gulf War demonstrated that OPEC was no longer able to play in the 1990s the role of balancer and regulator of the international oil system that it had played in the 1980s. The divergent interests of OPEC members has made price and production management increasingly difficult despite the powerful position of Saudi Arabia. Even that dominant country began to face financial problems in the 1990s as the price of oil declined and the Saudi budget grew faster than the growth in oil revenues.

Furthermore, because OPEC's share of the world oil market was smaller in the 1990s than in the 1970s and 1980s, price management would increasingly require the cooperation of non-OPEC producers. Such cooperation could not be guaranteed, however, since many non-OPEC producers, like the United Kingdom, Norway, and Mexico, continued to pursue independent strategies. In Mexico, the NAFTA treaty, which opened up sectors of the oil industry to foreign investment, combined with the aftermath of the 1994 peso crisis to make it difficult for the Mexican government to think of cooperating with OPEC to bolster oil prices.

Equally critical for the future of OPEC was the question of world demand and supply. In the 1980s and early 1990s, as the world supply of oil increased but OPEC s share decreased, the oil market became more like that of other commodities. That is, the oil market was subject to the sort of price volatility caused by temporary fluctuations in demand and supply that existed in world copper or bauxite markets, for example. Soaring oil prices in the 1970s led to a decline in demand in the 1980s due to conservation and substitution, and also to an increase in supply due to new exploration and production, resulting eventually in declining prices. Conversely, the lower price of oil in the 1980s encouraged greater consumption, discouraged investment in exploration and production, and contributed to the depletion of reserves that threatened to constrain supplies in the 1990s.

As the 1990s advanced, however, several new factors emerged. Growth in consumption, especially on the part of the rapidly growing NICs of Asia, continued unabated. However, possible new sources of supply—particularly in the oil-rich regions of the former Soviet Union (especially Kazahkstan, Azerbaijan, and Russia itself)—loomed on the horizon. Today, in the aftermath of the breakup of the Soviet Union, these regions may eventually open up to the kind of investment flows that are necessary to bring production capacity up significantly. But formidable legal, political, and financial barriers remain. Thus, it remains to be seen what role these countries will play not only in the supply but also in the politics of oil.

The success of the oil producers in the 1970s led to a revolution in the thinking of Southern raw material producers. Suddenly it seemed that producer cartels could bring the end of dependence. Producer organizations in copper, bauxite, iron ore, bananas, and coffee were either formed or took on new life after October 1973. In a variety of United Nations resolutions, the Third World supported the right of Southern exports to form producer associations and urged the North to “respect that right by refraining from applying economic and political measures that would limit it.”44

Yet by the late 1970s the prospects for these new producer cartels seemed dim. None had succeeded in maintaining higher commodity prices in the face of depressed market conditions, most were fraught with internal dissension, and a few never even got off the ground. Still, it is worthwhile to examine both their potential and the reasons for their very limited successes. First, it is necessary to review the reasons for the success of the oil producers and thereby to develop a model for effective producer action.

Several market factors set the stage for OPECs success in the 1970s. The demand for oil imports was high. Oil imports played an important and growing role as a source of energy in the North. Europe and Japan were dependent on foreign sources for oil. Even the once self-sufficient United States had become increasingly dependent on oil imports. In the medium term, the demand for oil and oil imports is also price inelastic. There are no readily available substitutes for petroleum, and there is no way to decrease consumption significantly. Thus an increase in the price of oil does not immediately lead to a noticeable decrease in demand.

Supply factors also favored OPEC in the medium term. The supply of oil is price inelastic; that is, an increase in its price does not lead to the rapid entrance of new producers into the market. Large amounts of capital and many years are required to develop new sources of oil. In addition, supply inelasticity was not relieved by the stockpiles of oil. In 1973, the developed countries did not have oil reserves to use even in the short run to increase supply and alleviate the effect of supply reductions.

Finally, at the time of the OPEC price increases, there was an extremely tight supply of oil in the international market. Rapidly rising demand in the consum-ing countries was not matched by rising production. As a result, a few important producers, or even one major producer, could be in a position to influence price by merely threatening to limit supply.

This economic vulnerability of consumers set the stage for OPECs action. Several political factors, however, determined whether such action would take place, and an understanding of the behavior of interest groups helps explain the ability of the oil producers to take joint action to raise the price of oil.45

First, there is a relatively small number of oil-exporting countries. Common political action is more likely when the number of participants is so limited, as the small number maximizes all the members' perception of their shared interest and the benefits to be derived from joint action.

The oil producers were also helped by the experience of more than a decade of cooperation. OPEC encouraged what one analyst described as “solidarity and a sense of community.”46 It also led to experience in common action. Between 1971 and 1973, the oil producers tested their power, saw tangible results from common action, and acquired the confidence to pursue such action. This confidence was reinforced by the large monetary reserves of the major producers. The reserves minimized the economic risks of attempting some joint action such as reducing production or instituting an embargo. The reserves were money in the bank that could be used to finance needed imports if the joint effort to raise the price of petroleum was not immediately successful. According to one analyst, it enabled the oil producers to take a “long-term perspective,” to adopt common policies in the first place, and to avoid the later temptation of taking advantage of short-term gains by cheating.47

The common political interest of the Arab oil producers in backing their cause in the conflict with Israel reinforced their common economic interest in increasing the price of oil. The outbreak of the 1973 war greatly enhanced Arab cohesiveness and facilitated the OPEC decision of October 16 to raise oil prices unilaterally.

Group theory suggests, however, that the perception of a common interest is often insufficient for common action. A leader or leaders are needed to mobilize the group and to bear the main burden of group action. Leadership was crucial to common oil-producer action. In 1973, the initiative by Arab producers in unilaterally raising prices made it possible for other producers to increase their prices. After 1973 the willingness and ability of Saudi Arabia to bear the major burden of production reductions determined the ability of producers to maintain higher prices.

Producer action was facilitated by the nature of the problem. Manipulating the price was relatively easy because it was a seller's market. Given the tight market, it was not necessary to reduce the supply significantly to maintain a higher price. Ironically, the international oil companies also helped joint-producer action. Producing nations were able to increase their price by taxing the oil companies. The companies acquiesced because they were able to pass on the tax to their customers.48 Producing nations were also able to reduce the supply simply by ordering the companies to limit production. Increasing governmental control of the companies helped implement these reductions.

Finally, the success of the producers was assured by the absence of counter-vailing consumer power. The weakness of the corporations and the consumer governments was demonstrated by the Libyan success in 1970 and by subsequent negotiations. The disarray and acquiescence of the oil companies and the oil-consuming governments in 1973 sealed the success of the producing nations. Particularly important was the inability of the developed market economies to take joint action—in contrast with the group action of the producers—to counter the cartel.

In the aftermath of OPEC's success, several factors seemed to suggest that in the short term, and perhaps in the medium term, some producer cartels might succeed. In the near term, economic conditions were propitious for many com-modities, particularly for those on which consuming states are highly dependent. The United States, for example, relies on imports of bauxite, tin, bananas, and coffee. Western Europe and Japan, less well endowed with raw materials, depend also on imports of copper, iron ore, and phosphates. Disrupting the supply of many of these commodities, particularly critical minerals, would have a devastating effect on the developed market economies.

In addition, over the short and medium terms, the demand for and supply of these commodities are price inelastic. As discussed earlier, with few exceptions, a price increase for these materials would not be offset by a decrease in con-sumption, which would lead to an increase in total producer revenues. Similarly, when supply is price inelastic, a rise in price will not immediately lead to the emergence of new supplies, because it takes time and money to grow new crops and exploit new mineral sources. It should be noted that for some critical raw materials, an inelasticity of supply can be cushioned by stockpiles, and devel-oped countries have accumulated such supplies for strategic reasons. Nevertheless, although stockpiles can serve to resist cartel action over the short term, not all commodities can be stockpiled, and stockpiles in many commodi-ties are generally insufficient to outlast supply interruptions that persist for more than a few months.

Tight market conditions favor producers in the short term. As demonstrated by the oil action, a seller's market facilitates cartel action by enabling one or a small number of producers to raise prices, as occurred in 1973–1974. At that time, the simultaneous economic boom in the North and uncertain currency markets that encouraged speculation in commodities led to commodity shortages and sharp price increases. The developed countries were particularly vulnerable to threats of supply manipulation, and the producer countries were in a particularly strong position to make such threats. For example, Morocco (phosphates) and Jamaica (bauxite) took advantage of this situation to raise prices.

In addition to these economic factors, several political conditions also favored producer action, again primarily over the short run. For many com-modities—for example, bauxite, copper, phosphates, bananas, cocoa, coffee, natural rubber, and tea—relatively few Southern producers dominate the export market, and some of these producers have formed associations with the goal of price management. Several political developments made producer cooperation more likely in the mid-1970s. One was a new sense of self-confidence. The OPEC experience suggested to other producers that through their control of commodities vital to the North, they might possess the threat they had long sought. Thus, many Third World states felt that they could risk more aggressive policies toward the North.

Another new development stemmed not from confidence but from desperation. The simultaneous energy, food, recession, and inflation crises left most Southern states with severe balance-of-payments problems. Some states may have felt that they had no alternative to instituting risky measures that might offer short-term economic benefits but that would probably prove unsuccessful or even damaging in the long run.

Reinforcing economic desperation was political concern. Political leaders, especially those in the Third World, tend to have short-run perspectives, as the maintenance of their power may depend on achieving short-term gains despite inevitable long-run losses.49 However, this argument is directly opposite to the OPEC model for a successful producer cartel, wherein monetary reserves enabled the producing nations to take a long-term perspective, to risk short-term losses for long-term gains. In other cases, producers with huge balance-of-payments deficits may be moved to risk long-term losses for short-term gains. And as has been argued, the short-term maximization of revenues may in fact be rational action for the long-term view; that is, if producers feel that their short-term profits will be sufficient to achieve economic diversification and development, they may rationally pursue short-term gains.50

The emergence of leaders in some producer groups was yet another new development. Jamaica's unilateral action in raising taxes and royalties on bauxite production and Morocco's unilateral action to raise the price of phosphate altered the conditions for other bauxite and phosphate producers.

Finally, cooperation was sometimes made easier by the nature of the task of managing price and supply. In commodities such as bauxite and bananas, verti-cally integrated oligopolistic multinational corporations could be taxed according to the OPEC formula. In these and other commodities, production control was facilitated by increasing governmental regulation or ownership of production facilities.

With all of these factors working in favor of cartel success, why then were the raw-material producer associations so unsuccessful after 1974? Some of the reasons for the problems of cartels can be traced to the depressed economic conditions of the late 1970s and 1980s, whereas others are of a more general nature.

Although as we have noted, the demand and supply of many commodities are price inelastic over the short and medium terms, in the long run, the demand and supply are more elastic and thus less conducive to successful cartel action, as is illustrated by the OPEC experience of the 1980s. A rise in price above a certain level will generally lead to a shift in demand to substitutes. Aluminum will be substituted for copper; coffee will be replaced by tea. With time, it is also pos-sible to develop new sources of supply for most commodities. New coffee trees can be planted; new mineral resources, including resources in the seabed, can be exploited. Of course, some of these new supplies may be relatively more expen-sive, as new production will often have to rely on costly technologies and lower-quality ores. Thus, it should be noted, new production may undermine a cartel, but it may have little effect on price.

Because of the long-term elasticity of demand and supply, the successful survival of a cartel generally depends on two complex factors. First, producers have to manage price so that it does not rise above a level that would encourage the use of substitutes. Such management requires sophisticated market knowl-edge and predictive ability. Because the threshold price may be lower than the preferred price for many producers, agreement on joint action may be quite difficult to achieve. Second, and equally difficult, the supply response from other producers must be managed. Currently existing cartels have been generally unable to manage successfully either prices or supply: price cutting among fellow cartel members has been common, and few producers have agreed to supply controls.