![]()

On January 8, 2001, Jason Newsted told James Hetfield, Lars Ulrich and Kirk Hammett that he was leaving Metallica. The bassist had spent three months considering his decision – a good deal more time than his band mates did before offering him the job back in 1986 – and by the time he convened with them for the first time since Christmas he was certain of it. This was not a negotiation. Newsted was out of Metallica. He was a dot. He was gone.

It is tempting to review the decision of the Michigan-born musician to finally sever ties with the band and think, ‘Good for you.’ In one sense Newsted had never been forgiven for being the beneficiary of the tragic circumstances that brought him to Metallica in the first place; over time this source of resentment had calcified into spite. Too many were the occasions that Hetfield, Ulrich and (to a lesser degree) Hammett were able to use their always ‘new’ bassist’s fundamental kindness and decency as a rod with which to punish a ‘whipping boy done wrong’. The fact that he was never afforded full partnership in the group meant that when factions arose they did so with the numbers uneven. It never occurred to James Hetfield that had Newsted been a figure of greater authority he would have been an ally in the power-struggles with his drummer and lead guitarist over the matter of the band’s public identity in the years of the Load and Reload albums.

While his band mates threw back vodka and whisky, Jason Newsted was forced to swallow his pride. This he managed to do without ever seeming to compromise his own dignity or sense of personal identity. A man whose destiny to one day stand onstage as a member of Metallica seemed pre-ordained, Newsted was the very embodiment of the ‘team player’. It was with grace that he rationalised his band mate’s constant rebuttal of the riffs he would submit for use in songs – over the course of fifteen years his name appears on the writing credits of just three Metallica compositions – reasoning that while he may not have supplied the source material heard on the band’s albums (and thus neither did he reap the rewards of songwriting royalties) he saw it as his job to help fully realise whatever songs were chosen by the band.

But when James Hetfield’s need for absolute control strayed outside the perimeter of the Metallica compound, Newsted found himself suffocating. As diktats were issued as to what he could and could not do under his own musical wing, the bassist found himself resenting a man he had previously not only respected but also idolised. At this point, the game was up.

‘As [the band] became more popular we were taken away from actually plugging in [and playing music],’ he recalls. ‘In my eyes, that was the demise. Less and less time plugged in with volume, looking at each other, making music. It didn’t have the same heart for me . . . I don’t know what they were doing instead. I was playing. I was making music for other people. I never stopped; I still haven’t. I play drums more than Lars does any fucking day of the week. I play music all the time. That’s my deal.’

There were also other internal issues within Metallica that Jason Newsted regarded with a mixture of quiet despair and bristling contempt. With the always complicated relationship between Hetfield and Ulrich entering a trough that seemed deeper than usual, Q Prime decided to call in outside help. As with so much else regarding the workings of the Metallica machine, Newsted was not consulted on this matter. When he entered room 627 of the Ritz Carlton hotel in San Francisco to inform his colleagues that from this point he would be referred to in the press as ‘former Metallica bassist Jason Newsted’ he was surprised discover four people were waiting for his arrival: three musicians and one ‘Performance Enhancement Coach’. He was not impressed.

‘I said, “Who is this and what is he doing here?”’ recalls the bass player. ‘I said, “Excuse me sir, I don’t know you and you don’t know me and you don’t know our band and you have nothing to do with any of this so I’d like you to leave. I’m not trying to be rude, but get the fuck out of here.” [After this] he listened from the next room [while] I laid my shit down. We decided to have another meeting one week later and he was there again! It didn’t mean shit. He hadn’t been through anything, not one second of the life that we’d been through had he been through with us. He had no place being there.’

Newsted considered the reality of Metallica’s surroundings and felt yet further emboldened by his decision to leave. The fact that the four men who shared each other’s lives to a point of uncommon intimacy and intensity ‘could not just talk to each other’ without the help of a mediator ‘was one of the things that pissed me off more than anything’.

‘We couldn’t just hang out and talk about it?’ he asks, both animated and incredulous. ‘I told everyone [what might be on the cards] three months before I chose to make the announcement that I was leaving the band. No one reached out to me. No one called me and said, “Dude, are you sure? Don’t you think we should keep the band together?” Everybody fucking knew. No one tried to stop me.’

Eavesdropping on the proceedings unfolding in room 627, the Performance Enhancement Coach did not need letters after his name to realise that things could have been going better. On the other side of the door, the four members of Metallica were by now engaged in ‘a full and frank exchange of views’. Tempers were roused and voices raised. After pacing the floor and considering his options, the behaviourist swallowed hard and swung open the hotel room door. His presence was met by complete silence and four entrenched scowls.

‘Excuse me,’ said the visitor. ‘I respect what you’re doing, but I’m here for these kind of situations.’

It was at this point that Metallica as it had existed since October 1986 made its final collective decision. Silently, the four men signalled their consent. Just to be sure, Lars Ulrich, ever the conciliator, said, ‘Let him stay.’

In his chosen field, Phil Towle came highly recommended. His job was both simple and complicated: he was charged with uncovering methods by which highly skilled blue-chip organisations might learn to communicate and operate in a harmonious manner. In other words, he was paid to figure out how to make sure that multi-millionaires played nice. His work in this field took him to the fractious confines of Major League Baseball locker rooms, as well as the practice facilities of teams in America’s National Football League, the world’s most profitable sporting enterprise. In particular, Towle also worked with individual athletes such as former NFL defensive line man Kevin Carter, and coaches such as the Super-Bowl-winning former St Louis Rams gaffer, Dick Vermeil. The latter said of Towle that ‘Phil has not only helped re-hone my leadership skills, but also helped me deal with my personal hang-ups . . . He’s a winner!’ In the field of popular music, Towle also attempted (and failed) to come to the aid of Stone Temple Pilots and their then acutely drug-addicted front man Scott Weiland, as well as Tom Morello, the guitarist with Rage Against the Machine and Audioslave, who described the therapist as being a man ‘who as a friend [is] a great counselor, and [who] as a counselor [is] a great friend’.

In Metallica’s orbit Towle cut an incongruous figure. While Hetfield, Ulrich and Hammett appeared to be fit, relatively young men dressed in biker boots and Converse Chuck Taylor hi-top trainers, Towle dressed like a man forever ill at ease with the concept of ‘dress-down Friday’. A resident of Kansas City, Missouri, he carried himself with an unflappable air of professional level-headedness that stood in high-definition contrast to the sometimes infantile, but often profound, screeches of dislocation emanating from the frustrated faces of the three-man band.

For Metallica, though, Towle was their knight in a bright yellow jumper. At the time of the therapist’s arrival in the Bay Area, the trio were a shambles. That neither party had any real clue as to both the intensity and the duration of the course of therapy on which they were about to embark, what was obvious was that this was a union that had sailed its ship into the rocks.

‘I see it as my job to exist in the moment,’ says Towle, recalling the state of ruin that met him in San Francisco in the opening months of 2001. ‘I ask the question, “What do Metallica need today, and how can I help them achieve what it is they need today? How can I help the band today in a way that will mean that by tomorrow some progress has been made?” [But] in its complexity the situation with Metallica was unlike anything I’d ever seen, before or since. And I don’t expect to see anything like it again.’

It was at this time that Hammett revealed to Playboy magazine, ‘There are a lot of soap operas and petty dramas that come with being in this band.’ It was on this same (very) public forum that Ulrich would suggest that Hetfield’s quiet homophobia was due to the fact that the front man was less than sure of his own sexuality. ‘I know he’s homophobic,’ said the drummer. ‘Let there be no question about that. I think homophobia is questioning your own sexuality and not being comfortable with it.’ On the state of dysfunction evident in his band, James Hetfield conceded, ‘There is a little ugliness lately,’ before insisting, ‘And it shouldn’t be discussed in the press.’

At the time Metallica sat down with Playboy for what was inarguably their most revealing and startling interview to date, the group was a quartet; by the time Rob Tannenbaum’s piece was published, they were a trio.

‘I wasn’t surprised that Jason Newsted quit Metallica,’ Tannenbaum later admitted. ‘I’d spent a day with each of the four and I’ve never seen a band so quarrelsome and fractious. Most of the barbs were cloaked in humour: Newsted mocked Hetfield’s singing, Hetfield mocked Ulrich’s drumming, and Ulrich, whom I interviewed last, responded to several of Hetfield’s quotes with scorn. But genuine tension was evident at these interviews – the last ever to be conducted with this Metallica line-up – because they shared one trait; each talked about his need for solitude. Paradoxically, this is a band of loners, and the conflict between unity and individualism was pretty clear.’

Jason Newsted announced his departure from Metallica with a typically diplomatic and gracious statement. It read, ‘Due to private and personal reasons and the physical damage I have done to myself over the years while playing the music I love, I must step away from the band. This is the most difficult decision of my life, made in the best interests of my family, myself and the continued growth of Metallica. I extend my love, thanks and best wishes to my brothers James, Lars, Kirk and the rest of the Metallica family, friends and fans who have made these years so unforgettable.’

For their part, the remaining members of Metallica afforded the bassist the respect that he had always deserved. In a reciprocal statement released to the press, Lars Ulrich said, ‘We part ways with Jason with more love, more mutual respect and more understanding of each other than at any point in the past.’ Expression of this opinion begged the question, if this is so then why is Newsted leaving? The drummer added that ‘James, Kirk and I look forward to embracing the next chapter of Metallica with a huge amount of appreciation for the last [fifteen years] with Jason . . .’ In the same statement, James Hetfield told readers that ‘playing with someone who has such unbridled passion for music will forever be a huge inspiration. Onstage every night, he was a driving force to us all, fans and band alike. His connection [to both] will never be broken.’ For his part Kirk Hammett needed just eight well-chosen words with which to make his point. ‘Jason is our brother,’ he said, adding, ‘he will be missed.’

Despite these kind expressions of eternal fraternity, in old-fashioned parlance Metallica were burned out. The slights and miscommunications, the jealousies and competitiveness that existed between Hetfield and Ulrich about which of them owned Metallica, the emotional inarticulacy that had for years been pushed out of sight by a sea of alcohol and bowls of cocaine were finally coming home and were ready to roost. As the three-piece found themselves at the Presidio recording facility in San Francisco, the band attempted to begin work on a new album while at the same time embarking on a course of therapy with their new Performance Enhancement Coach. As if this weren’t all quite enough, the state of the band was about to be thrown into yet further chaos.

![]()

On the occasion of the first birthday of James and wife Francesca Hetfield’s second child, Castor, the boy’s father held in his hands not a birthday cake but a hunting rifle. Instead of being at home in Northern California, he had flown to Siberia on Russia’s eastern front. Each morning he would rise at dawn and with a troop of fellow hunters head out into the wilderness in pursuit of the Russian bear. Having secured their kill for the day, the party would be photographed around the animal’s strewn corpse before spending the rest of the day sinking shots of vodka. ‘There was’, Hetfield explained, ‘nothing else to do.’

Back at the family home, this and numerous other examples of Hetfield’s unilateral impulses meant a domestic scene that was less than blissful. Having previously given up alcohol for a year, he attempted to rationalise his situation – ‘It was okay to have a few glasses of wine with dinner because that’s what normal people do – which is how it all starts again’ – and duly hopped off the wagon. But this was okay, anyway, he internalised, because temperance didn’t cause ‘the skies to part’ and the only thing the front man learned from the experience was that ‘it was just life, but less fun’ and that ‘drinking is a part of me’.

‘I wouldn’t say I’m an alcoholic,’ was his ‘I’m-glad-that’s-all-sorted-then’ diagnosis, albeit one coloured with a measure of self-awareness.

‘But then, you know, alcoholics say they’re not alcoholics.’

They do, and he was one. Francesca Hetfield certainly knew that her husband was an alcoholic, and that things could not continue. As Metallica’s engines stalled in disagreement and disarray over the musical direction of their next album, Francesca threw her husband out of the house.

‘My wife finally told me, “Hey! I’m not one of your yes men on the road. Get the fuck out!”’ Hetfield recalled.

As he would subsequently admit, he was a ‘horrible’ influence on the children. With the help of a friend, Hetfield was able to find himself an apartment in which he would reside ‘for a long time’. His entreaties to return to the family home were met with a resolve from Francesca Hetfield that might as well have been made out of jade.

‘My wife said, “You’re not coming back until you sort this out”,’ he recalls. ‘You get some therapy. Not just the drinking, but all the other crap that goes along with it, you know. The disrespect, doing whatever you want whenever you want.” I had to grow up at some point. I had a family . . .’

So a man who it seemed had done his growing up in public decided to try a different tack. With his wife’s injunction reverberating in his ears, Hetfield removed himself to an undisclosed rehabilitation clinic and let it be known that he would remain there for as long as it took to untangle the many knots in his psyche, as well as learn how to face each encroaching night without the aid of alcohol. The front man also revealed that this was a period during which he would be separate from Metallica in a personal, musical and organisational sense. Bob Rock, for one, appeared devastated that his papers had been stamped ‘persona non grata’ until such time as Hetfield was able to once again face what he defined as ‘the business side’ of the band. Even closer to home, Lars Ulrich was empathetic to his friend’s plight, as well as being awake to the sense of genuine fear to which Hetfield’s life had succumbed (a fear which for years had been kept at bay by its twin brother, anger). But at the same time he could be forgiven for wondering what permanent damage had been caused by the shock waves emanating from Hetfield’s troubled core. It was far more than self-interest that led the drummer to look around the utter wreckage that was Metallica and marvel at what had happened to them and what would happen next.

Hetfield’s absence went from weeks to months, to many months. He could not, or would not, say when he might return to the flock, or indeed if at all. Bereft and bewildered, the Dane feared for the worst. He understood that Metallica ‘had had a good run’ but that maybe now it was time for the band to be spoken of in a different tense. A listless summer came and went, followed by a season that saw the clear Californian sky turn blotting-paper blue earlier each evening. In an attempt to shadow their front man’s intensive course of therapy, Ulrich and Hammett continued their own therapy sessions with Phil Towle.

‘Lars and Kirk did not just sit still while James was in rehab,’ says Towle, speaking to this book’s authors. ‘They wanted to embark on something themselves; they wanted James to come back and see that they too had made an effort to address the problems that were facing the band.’

But while Towle says that the efforts of Metallica’s drummer and lead guitarist should be applauded, it is Hetfield who, he believes, became ‘the poster boy for mental health’.

‘You have to remember’, he says, ‘that this was a time when people didn’t admit to undertaking that kind of intensive therapy. There was rehab, sure, where people went to give up drinking or drugs, but that was kind of all that was admitted to. James went to rehab to learn how to become a different person. A kinder person; a more gentle person. This angry person whose public image was all about strength and immovability suddenly admitted to personal failings, frailties and weaknesses. He showed people, “Hey, if I can admit to these things and seek help for them, then why can’t you?” By doing this he set a trend not just for celebrities and people in bands, but really for everyone.’

The week before Thanksgiving, Kirk Hammett celebrated his thirty-ninth birthday. To mark this occasion, on November 18, 2001, the lead guitarist hired a restaurant and bar in San Francisco. By the time the birthday man arrived at the venue, the room was already crowded with family and friends. Smiling in appreciation at the number of people that had chosen to spend their evening in his company, the man who was born and raised in the very city in which he now stood at first failed to notice that the crowd was parting to allow room for the one person he did not expect to be in attendance. There, standing directly in his line of sight, was a smiling Hetfield.

‘I had never been so pleased to see him,’ Hammett confessed.

![]()

This, though, was not the happy ending that would herald the start of a new life for the band. Almost a year on from the departure of Jason Newsted, Metallica were still without a permanent bass player, the search for which had not yet even begun. Although the three men had written a number of songs, none of them were particularly inspiring or even much liked. Days were ticking by as if seconds on a clock, and for the first time in their career the band was unable to use its collective force as a battering ram with which to obliterate any obstacle that lay in its path.

Hetfield had emerged from rehab in the autumn of 2002 a fragile and frightened man, shorn of the calloused skin that formed his armour of old. The front man described his time away from band and family as having been ‘college for my soul’, but now blinking into the light he was also aware that the lessons he had learned at the private clinic would have to be tested not just in Real Life but at the site of so many battles that had been lost in the past.

‘I’ve been in Metallica since I was nineteen years old, which can be a very unusual environment for someone with my personality to be in,’ he said. ‘It’s a very intense environment, and it’s easy to find yourself not knowing how to live your life outside of that environment, which is what happened to me. I didn’t know anything about life. I didn’t know that I could live my life in a different way to how it was in the band since I was nineteen, which was very excessive and very intense. And if you have addictive behaviour then you don’t always make the best choices for yourself. And I definitely didn’t make the best choices for myself. Rehab definitely taught me how to live.’

With regard to his relationship with Metallica, Hetfield realised that in order to flourish in an environment one must be unafraid of being separated from it for ever. In pursuit of this he ‘truly had to believe that I would survive without Metallica and that my health and well-being and my family was most important. I had to get my priorities in order, basically. I knew Metallica was my passion but I wasn’t going to allow it to still rule me in my mind and my reality. It took me a while to get to that point and I couldn’t come back until I had reached [it].’

In attempting to piece himself together as a better man, Hetfield mined his life for lessons that might be learned. He would recall seemingly comically incongruous moments from his childhood to apply to the person he was trying to become. He remembered sharing a car with a father who had become so short-sighted that he would literally speed past the off-ramp of a freeway because he was unable to read the words on the signs hanging overhead. (‘I’d be, like, Dad you just missed it!’ he recalled.) But the son realised that now he too would soon be at the point where he would have to buy books in audio rather than print form, and that like his father he had turned his face against this encroaching reality. In finally accepting this and buying a pair of glasses, the front man was able ‘to see things well, literally’.

For anyone abreast of the kind of yearning expressed in a number of the songs from Load and Reload, it was clear that Hetfield was becoming the person about whom he so often sung. He recognised that he was a flawed man with character traits both of strength and vulnerability, a figure burdened with instincts, some of which might prove fatal. For the less well-briefed, or the less imaginative, among Metallica’s core constituents, however, the James Hetfield that emerged sober and sensible from rehab struck a less than reassuring figure, like God overheard placing a call to the Samaritans.

He is quick to admit that in the past it suited him to present to the world an image of indestructibility, the kind of figure whose face might appear at home on the side of Mount Rushmore. ‘That’s what I wanted to be,’ he’ll say, ‘that’s what I needed in my life. That’s what I wanted to see. That’s what I wanted to portray.

‘Through all the instability of childhood I wanted something that was a rock, something stable,’ he adds. ‘But at the end of the day we’re all human and things change for a reason. With that perception blasted out of their mind [after he left rehab] I’ve no doubt that it turned off a lot of fans. I’d walk in somewhere and people would expect me to be this hard-ass who gets up on the table and demands beer for everyone. When you don’t do that it suddenly becomes a case of, “Wow, I thought you were different.” How much that hurts [me] is so amazing but they only mean it in a nice way. They get their perception the way they get it. They build their own perception of you [that is informed by] the way they need to see you. And when it’s different from that, it really shakes their world.

‘But I’ve learned that you have to be yourself. Whatever you put out, that’s what you’ll attract [in response]. It’s as simple as that, the law of attraction. If you’re putting out the image of the hard-ass that doesn’t want to bend and who would rather break [than do so], you’re going to attract the kind of fans that are looking for that kind of character. I realise now that all I can do is live and survive life.’

![]()

James Hetfield may have been empowered with a greater and healthier sense of self-awareness, but the question of how this new-look human being might fit back into the dynamic of his old band was a pressing one, not least because not everything about the front man was new. Whether by failure or design, the rehabilitation clinic in which he had been seconded for months on end did not reset his hard drive entirely. When Hetfield finally rejoined Ulrich and Hammett (as well as Bob Rock, now the band’s temporary bass player), it became obvious that the front man’s instinct to control all situations remained the same as it had always been.

In the past this was something with which the group could deal, not least because in Ulrich Metallica had another member capable of playing the unstoppable force to Hetfield’s immovable object. But as 2001 passed into a brand-new year, this long-enduring dynamic was further challenged by the question of how the front man might best be reintegrated into the band without jeopardising a recovery that had really only just begun.

The solution as Hetfield saw it was for Metallica to work on their now spectacularly delayed new album for just four hours each day, beginning at noon. This was a proposal to which Ulrich might have peaceably consented were it not for the fact that it came with one crippling caveat: that when their band mate was not at the studio, neither Ulrich, Hammett nor Bob Rock could tinker with the work in any way. In fact, Hetfield stipulated, they weren’t even to listen to that day’s recordings without him present in the room.

At this, a band that was already split into two camps split into two more. While not overjoyed at Hetfield’s terms and conditions, Hammett nonetheless believed they were wishes which should be adhered to, if only for the greater good. But for his part, Ulrich could do nothing other than regard his band mate’s condition as a wholly disheartening lack of faith in anyone but himself. ‘I feel so disrespected,’ he would say. Bob Rock simply could not understand what harm could be caused by listening to music when just one of the four people involved in its recording happened to be absent.

But these were Hetfield’s wishes, and here was the barrel over which he ultimately had the other three men. Whereas in the past recording sessions would last for up to twenty-four hours, in 2002 Metallica and Bob Rock would convene for just 240 minutes each working day. It was in this restricted space that these old dogs somehow learned the new trick of making music in a different way. The pace may have been glacial, but inch by inch and week by week Metallica’s new album began to take form.

![]()

After more than a year, and with only the dots and crosses missing from a collection that by now had been given the title St Anger, Metallica convened for their first concert since performing a private show for members of their fan club at their new group headquarters in San Rafael, California – the location at which St Anger was recorded – in April the previous year. For the third time, on January 19, 2003, the band’s equipment trucks made their way to the Oakland Network Coliseum. It was here that tens of thousands of Oakland Raiders fans had gathered for an American football play-off game against the Tennessee Titans.

As is the case at NFL stadiums from Secaucus to Seattle, supporters arrived early to tailgate – the particularly American practice of firing up a barbecue over which steaks the size of phone directories could be cooked medium-rare and eaten with beers icy from hours in a cool box. When the team were the Los Angeles Raiders, tailgate parties outside the LA Coliseum would often end in fist-fights and virtual riots; but when the Southern Californian incarnation of the team began to post losing records, in time the crowds dwindled to the point where it seemed that more people were on the field than in the stands, a typically ‘LA’ phenomenon. Since returning ‘home’ to Oakland in 1995, the club’s image may have softened somewhat – with its fans more often cited for misdemeanours rather than felonies – but the notion that the Oakland Raiders and their pirate logo represented the NFL’s most rough ’n’ tumble franchise remained intact. This image, of course, fitted James Hetfield like a tailored suit, and was the one outlaw quality he was able to spare from the funeral pyre of his old self set ablaze in rehab. As the ideal occasion at which to announce the fact that Metallica were back on the chain gang, a Raiders play-off game was tough to top. The group’s original plan was to perform on the Coliseum field at half time (not to mention live on network television) but instead the decision was taken to play before the game on a flat-bed truck in the parking lot. Dressed in the Raiders’ uniform of black shirts with silver numbers, the makeshift quarter further energised a crowd already alive with electricity with a six-song set that included ‘Battery’, ‘Seek & Destroy’ and ‘Fuel’.

But if Metallica’s public and private selves were finally beginning to unify, other concerns were ongoing. By this point it had been more than two years since Jason Newsted had left the band, and for those two years Bob Rock had played bass on their new album. But with St Anger almost a wrap, and a summer tour of the largest stadiums in North America soon to be announced, the group’s need for a permanent fourth member was now a code-red matter of priority.

![]()

On the last Saturday of February 2003 one of this book’s authors is on a British Airways flight from London Heathrow Airport to San Francisco International Airport to interview Hetfield, Ulrich and Hammett. This purpose is explained to the white-shirted representative of the US Department of Immigration & Naturalization sitting in a booth checking the passports and stories of those wishing to visit the City by the Bay. ‘Really?’ he says, nodding his head slightly. Asking the Englishman to place the fingers of his right hand on a green scanner that stands at shoulder height, the official asks, ‘So who do you think will be the new Metallica bass player?’ The visitor replies that in all honesty, he has no idea. The official nods his and says, ‘I think Pepper Keenan will get the job.’

The interview for which the writer has flown 6,000 miles will be Metallica’s first since the dishearteningly shambolic front presented in Playboy two years earlier. It is a world exclusive, an audience with one of the most popular and forensically examined bands of the day at the time of their most uncertain hour. It has been revealed to the press that the group’s eighth album of original songs, St Anger, will meet its expectant public at the start of the summer. It is also known that the quartet will tour the world for the first time in three years. Following a four- night tune-up at the Fillmore in San Francisco, the group will fly (once again, by private jet) to Europe for a month of appearances on the bills of numerous grandly lucrative festivals. As well as this, the band will perform three concerts in one day, in Paris on June 11. Rumours have also begun to circulate that the San Franciscans will headline the Leeds and Reading festivals on the final weekend at the end of the English summer.

The docket for activities to be undertaken in the US is even more impressive. Metallica will return to the road in North America not with a series of dates at arenas, or even amphitheatres (the ‘sheds’), but with a twenty-one-date tour of twenty of the largest stadiums on the continent. The 2003 Summer Sanitarium tour will see the headliners perform on the same stage as Limp Bizkit, Linkin Park, Deftones and Mudvayne, younger bands all. It is also understood by everyone that in order to undertake these live commitments Metallica will require the services of a bass player other than Bob Rock.

The identity of the man chosen as the replacement for Jason Newsted, it was explained, was as yet undecided: the writer’s world exclusive would be conducted with three, not four, musicians. Despite this disappointing news, en route to HQ, Metallica’s studio and business facility in San Rafael, it’s difficult not to smile and think, ‘Well, a scoop is still a scoop!’ as the car travels over the Golden Gate Bridge and through the iconic rainbow arch of the Waldo Tunnel. As Hetfield himself once sang, this is ‘a good day to be alive’.

It is an even better day to be alive when it is revealed that today’s interview for Kerrang! magazine will be the very first to feature a contribution from Metallica’s new bassist. This is the age before social media, so although the news will leak out it will not explode into the sky like a bomb in a fireworks factory. The pictures taken by Kerrang! photographer Paul Harries will be the first sessions for which the group have posed. The image of the four men crowding the cover of the magazine – across which is splashed the legend: ‘Metallica:. New Line Up. New Album. New Danger’ – will be the first image that British and Irish readers will see of Metallica 4.0.

Clearly, the group had taken their own sweet time choosing a fourth member. At HQ, throughout the autumn and winter of 2002, potential recruits such as Corrosion of Conformity’s Pepper Keenan, Marilyn Manson sidekick Twiggy Ramirez (aka Jeordie White), Kyuss’s Scott Reeder and Nine Inch Nails’s utility man Denny Lohner were first asked to break bread with Hetfield, Ulrich and Hammett and then invited to make music. Those that most impressed as men and musicians were invited back for a second time. By this point, though, it was clear that the abilities of one applicant stood higher than those with whom he was in competition. It quickly became clear that Metallica had found their fourth bass player.

![]()

Robert Agustin Trujillo was born on October 23, 1964, in Santa Monica, California. Described by his mother as being ‘a really good boy’ who never once ‘caused any problems for me’, from the youngest age the son showed an appetite for whatever music he happened to hear. At home the family stereo would bounce to the sounds of James Brown, Led Zeppelin and the infectious grooves of Tamla Motown, the beat of which would send him dancing from room to room. As an infant, on a visit to Disneyland in nearby Anaheim, Trujillo danced alone and without a care to a band playing Disney standards while every other child in the theatre watched from a sedentary position.

With the Pacific Ocean just a Frisbee throw away, Trujillo occupied his time surfing the waves of both Santa Monica and neighbouring Venice Beach, and it was from this latter location that he picked up the habit of skateboarding. These teenage years lacked either drama or danger, and by the time he was sixteen he had cut back on the hours dedicated to waves and half-pipes and instead set his sights on a career as a professional musician. Profoundly inspired by the music of jazz composer and bass player Jaco Pastorius, he soon mastered a command of this instrument to a level sufficient for him to perform with other friends at teenage backyard parties. But instead of songs by Kiss or Black Sabbath, he would lead these groups into cover versions of songs by Eric Clapton.

By now Trujillo was a student at Venice High School, one of the tougher seats of learning in an area known as ‘Urban LA’. Venice – so named because one of its founding fathers, conservationist and developer Abbot Kinney, envisioned the location as being the Venice of the West Coast – was also the home to what was at first one of Los Angeles’ most remarkable bands.

Formed in 1981 by vocalist Mike Muir, Suicidal Tendencies were a group of such unharnessed fury as to make Metallica sound like the Partridge Family. Like Metallica, the group fell between two stools. Ostensibly a hardcore punk band – and a very hardcore punk band at that – the appearance of lead guitar solos in many of the band’s songs drew charges of heathenism and heresy from the scene’s moral arbiters. Married to this was a sense of confusion regarding the group’s visual image. That many among Suicidal Tendencies audiences dressed as the band did in baggy board shorts and bandanas led many to conclude that ‘ST’ were a band with an affiliation to gang culture, a misconception that for years hampered the group’s ability to perform in and around Los Angeles. Always a man with a pronounced persecution complex, Mike Muir railed against this state of affairs in the manner of a man rather enjoying protesting so much.

At the start of the Eighties the punk scene in Los Angeles was by far America’s most impressive and varied, not to mention often its most pointlessly violent and nihilistic. But despite LA having found the space for bands ranging from the stare-at-the-wall fury of Black Flag to the artful buzz of X, Suicidal Tendencies proved to be a touch too much. When the group released their self-titled debut album in 1982, readers of the underground magazine Flipside promptly voted it the worst record of the year. Even those who believe themselves to be on the cutting edge can sometimes be bamboozled by music that not so much defies convention as seems ignorant of its very existence in the first place. Suicidal Tendencies remains one of the most incendiary albums of the Eighties, as well as one of its most surprisingly successful. Powered by MTV’s unlikely decision to playlist the band’s alienation-überalles anthem ‘Institutionalized’, the record found its way into the bedrooms of more than 100,000 listless teenagers in the US alone.

Robert Trujillo became a member of Suicidal Tendencies at the time of the band’s third album, Controlled by Hatred/Feel Like Shit . . . Déjà Vu. But with their music veering towards thrash metal cliché and turbid rock mediocrity, this was not a high point in their career. With Trujillo’s help, the group were able to reverse their fortunes with 1991’s Lights, Camera, Revolution album, the point from which the quintet began to find favour with a larger and newer audience. An invitation to appear as the opening act on 1994’s Shit Hit the Sheds tour provided the occasion at which Trujillo and Metallica would first meet.

![]()

By 2001 Robert Trujillo had swapped his gig with Suicidal Tendencies for the position of bassist in Ozzy Osbourne’s band. This was a world of private jets and high-end musicianship in the form of guitarist Zakk Wylde and one-time Faith No More drummer Mike ‘Puffy’ Bordin. For his part Ozzy had been reinvigorated by the advent of his own summer Ozzfest tour, a shed-filling caravan that heralded a renaissance in the headliner’s fortunes that was as perplexing and it was pronounced. By any measure, Trujillo had ‘made it’.

By any measure, that is, except the standard set by Metallica. After receiving the blessing of Sharon Osbourne in 2002, Trujillo decided to audition for the role of bass player for the biggest name in metal. Flying north to the Bay Area, at HQ, the visiting musician was asked by Lars Ulrich which of their songs he might like to play. The bassist’s shy mannerisms made him appear younger and far less established than he actually was. But the answer came back, ‘I could try “Battery”.’ As the group smashed their way through one of Metallica’s most formidable and enduring songs, Ulrich felt honour-bound to observe, ‘That’s a fucking pretty fuckin’ mighty bass sound you’ve got going there.’ As the three musicians shared meaningful glances, Bob Rock sounded a note of caution. ‘I don’t think you should [just] settle [for someone].’ He added, ‘I think you should get the right guy. If you don’t hit it out of the park with one of these guys [that you’re auditioning] then you’re going to end up four years down the road in the same situation you did with Jason.’

But as auditions went on, it was Trujillo whose presence began to dominate the sessions. ‘He was the [one] guy out of [all] of them who didn’t look like he was struggling with [the music],’ observed Ulrich, adding, ‘With some of the other [candidates] it was like they were [playing at] ten per cent over their capabilities or something . . . I don’t feel that with this guy.’

Robert Trujillo became Metallica’s fourth bass player on February 24, 2003. Giving the appearance of a man who had just been told that he’s sitting on a landmine, the Santa Monican sat in stunned silence as Hetfield told him that the second time he came back to audition was when he noticed that he made the band ‘play better, man’ and that this meant that he could ‘make the band sound so much better . . . sound so solid’.

‘How do you feel about that?’ asked Hammett.

‘I feel awesome, man,’ came the answer from the mouth of a man who at that moment appeared to have very few words at his disposal.

Not to worry, though, because as ever Lars Ulrich was on hand.

‘We want you to be a real member of the band and not just a hired hand,’ he told the guest. ‘Basically, to show you how serious we are about this, we’d like to offer you a million dollars.’

Hearing these words, Robert Trujillo made a strangulated sound somewhere between joy and disbelief. He was utterly astonished. Running his hands through what is now the best head of hair in Metallica, he struggled to compose himself, and failed. As if expecting to hear the sound of a bedside alarm clock at any moment, he admitted to the people with whom he would now share his life, ‘I can’t even talk right now.’

![]()

To enter HQ is to be struck with immediate force by just how wildly successful a band this is. The space is vast. On two storeys and covering thousands of square feet, the gated complex teems with trinkets and mementos from its owners’ diamond-encrusted past. The walls are covered in frames holding Metallica concert posters stretching back over two decades. In one of the two large, high-ceilinged sound rooms is propped the head of ‘Edna’ the towering ‘Lady Justice’ figure that adorns the cover of . . . And Justice for All and which comprised part of the stage show for the band’s Damaged Justice Tour of 1988 and 1989. A grand piano stands majestically in the other sound room, as do racks holding literally scores of guitars: Gibson Explorers, SGs and Les Pauls; Fender Stratocasters, Telecasters; signature ESP models; hollow-bodied acoustic instruments the value of which runs to thousands of dollars each. There are more drums than there are hairs on Lars Ulrich’s head. To capture the sounds made by these and other instruments, one room is crowded with recording equipment of such sophistication that it appears to have been sourced from NASA. An anteroom is given over entirely to the kind of equipment required to undertake running repairs. In here there are boxes and boxes of guitar strings, drum heads and foot-pedals. Stacked on a shelf are boxes of plectrums (each one adorned with the band’s original logo); next to this sits a box stuffed with the elbow-length sweat bands that have been part of James Hetfield’s stage attire since 1988. On one of HQ’s many corridor walls are hung frames of albums by other artists – Jethro Tull’s Aqualung, Saxon’s Denim & Leather and Led Zeppelin IV being three – that suggest that although it may often sound as if they did, Metallica did not parachute into the world from an otherwise empty sky.

At the top of a wooden flight of stairs are four spacious ‘bedrooms’. It is here that each member of the band has his own private room. Hetfield’s space is the first door on the left; the walls of it are currently being painted with cartoon images of men in speeding cars, each decorated in garish colours. Ulrich’s room is at the end of the hall, and in here he will sit on a sofa that seems to be about to swallow him whole at any moment.

Robert Trujillo has his own room, too, although he still looks as if he can’t quite believe it.

‘Metallica called me a couple of days ago,’ he explained for what is his first interview as a member of his new band. ‘They said, “Can you get up here in the next twenty-four hours?” I flew up [from Los Angeles] the next morning.’ Hetfield told the bassist that he wanted him to be ‘a part of the Metallica family’, words that left the bassist ‘overwhelmed’.

Today, it is explained to the Kerrang! journalist who will break this story, each member of Metallica will be interviewed separately, with each subject answering questions in private rooms. After this comes another revelation, this one less routine. Each interview will be filmed, with Metallica at liberty to use any part of the footage they desire. The director asks the journalist to pose for a photograph and to sign a release form. Shaking hands, he introduces himself as Joe Berlinger.

As if this weren’t all quite startling enough, a day that is already by turns exhilarating, intense, intimidating and bewildering reaches its apogee when Lars Ulrich asks if the journalist would care to hear a selection of songs from St Anger. The album isn’t yet quite finished, he explains, but four or five rough mixes can be easily cued up. (Well, sure, why not?) In a mixing room, sitting on a high-backed leather chair at a console the size of the wingspan of a pterodactyl, with Ulrich and Bob Rock seated on a black leather sofa directly behind, the journalist realises that this is the first time anyone outside the Metallica camp has heard these songs, and that after an interminable gestation period producer and drummer are keen to see how the music they have recorded is received. A film of sweat prickles the brow. Critical faculties have not so much been suspended as extinguished.

A technician cues up the first song: ‘St Anger’ drops like a bouncing bomb from the speakers. Every time the journalist turns around – surreptitiously turning the chair on its castor wheels – he notices that Ulrich and Rock are looking directly at him. So the most difficult task in a music journalist’s work book – knowing quite what to say when hearing recorded music for the first time in the company of the people who recorded it – is made even trickier when the pair break the silence that greets the conclusion of ‘St Anger’ by asking for an opinion. ‘It’s amazing,’ the pair are told. ‘It’s incredible.’ So certain is this opinion that just weeks later the first Metallica feature to be published since 2001 features the sentence, ‘“St Anger” is the finest thing to which the band have [ever] put their name.’

As is now known, St Anger the album is in fact the worst thing to which Metallica have put their name. But with their first release of the twenty-first century this was a group in receipt of a number of fortunate breaks. One of these was the human fallibility of the rock press, and the fact that many writers (most writers, actually) were fans of the band in the first instance and as such naturally discounted the notion that the group’s creative instincts could no longer be trusted. Another factor that came into play was that since their rhubarb with Napster, Metallica were a band obsessed with the fear that the music they had recorded might ‘leak’ on to the Internet before its official release date. Because of this, for the first time in the group’s history no magazine or journalist was given an advance copy of St Anger that he or she could call their own. Instead, in order to hear Metallica’s latest collection of songs reviewers were required to travel to the office of the band’s PR person near Paddington in west London and listen to the CD through headphones in an office busy with working people. St Anger endures for seventy-five minutes and one second and is in many ways the musical equivalent of primal scream therapy. It is not an album designed to be heard in one sitting, and certainly not on a first date. Critics who were forced to do just this found their senses concussed by the conclusion of the third song and comatose by the end of the sixth. But rather than succumb to suspicions and fears that would soon enough be recognised as justified and correct, instead reviewers and writers erred on the side of kindness.

Metallica at the MTV Music Awards, September 5, 1991. The quartet performed their new single ‘Enter Sandman’ at the ceremony in Los Angeles.

Jason Newsted onstage at London’s Wembley Stadium, at the Freddie Mercury tribute concert held on April 20, 1992. Other performers included Guns N’ Roses, Def Leppard and Spinal Tap.

Lars Ulrich and James Hetfield relaxing backstage at the Oakland Coliseum on September 24, 1992, ahead of show 21 of Metallica’s co-headlining tour with Guns N’ Roses.

Hetfield (on drums) jamming with Kirk Hammett and John Marshall, backstage at the Oakland Coliseum on the same afternoon. Metal Church guitarist Marshall was drafted into the band to play rhythm guitar after Hetfield was injured onstage at Montreal’s Olympic Stadium on August 8, 1992.

Metallica at the 35th annual Grammy Awards, February 24, 1993.

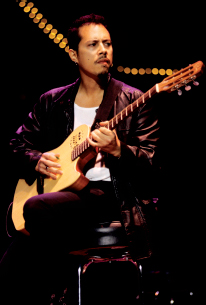

Kirk Hammett unplugged, at Neil Young’s Bridge School Benefit, October 18, 1997.

The band onstage at London’s LA2 club on August 23, 1995, ahead of their ‘Escape from the Studio’ show at Donington Park.

‘The Little Engine That Could’: Lars Ulrich, shot in London, July 1, 2003.

‘Papa Het’: James Hetfield onstage at the Amsterdam Arena, The Netherlands, June 21, 2004.

Trujillo, Ulrich, Hetfield and Hammett in Istanbul, Turkey, July 27, 2008.

Robert Trujillo on stage at Madison Square Garden, New York, November 14, 2009.

Slayer’s Kerry King, Megadeth’s Dave Mustaine, Anthrax’s Scott Ian and Metallica’s James Hetfield at Bemowo Airport, Warsaw, Poland at the first ‘Big Four’ show, June 16, 2009.

Lou Reed with Kirk Hammett at the second of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s 25th Anniversary Concerts at Madison Square Garden, New York, October 30, 2009.

Dave Mustaine and James Hetfield at the Fillmore, San Francisco, on December 10, 2011, the final night of Metallica’s four thirtieth-anniversary concerts.

the band onstage at the Fillmore that same evening.

The Hetfield Family at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony, at the Public Hall, Cleveland, Ohio, on April 4, 2009.

The Ulrich family at the 56th annual Grammy Awards ceremony, held at the Staples Center, Los Angeles, on January 26, 2014.

‘Even the fact that for the first time in fifteen years Metallica actually thrash on several of these songs cannot disguise the fact that this is a band revived, not merely renewed,’ was the opinion of Kerrang! writer Dom Lawson, who awarded the album a ‘four out of five’ rating in his review. This was just one of numerous notices whose hyperbole would prove overblown. The album, Lawson decided, was ‘the work of a group rediscovering what made them special in the first place [but] rather than making some obsequious, conciliatory gesture towards their original fanbase, [instead had rebuilt] their sound from scratch. No ballads, no orchestras and no fucking country music. Somewhere up in the ether, Cliff Burton is taking a hit from a celestial bong and grinning from ear to ear. Welcome home, boys.’

In the days and weeks that followed the release of St Anger on June 5, the air leaked from Metallica’s bubble with a determined and sinister hiss. Yes, it was noted, the band was back. But with what? This was a release of such a complex and contradictory nature that it could not be dismissed merely with a grimace and a shudder. In one sense St Anger is arrogant in its self-confidence, with songs that enter the room like a noisy guest at a Christmas party who insists on staying until Burns’ Night. Here we are, the band seems to say, pushing our noses into an endless slurry of riffs each underpinned by a drum sound that is the musical equivalent of someone placing a tin bucket over your head and hitting it repeatedly with a trowel.

But in another sense the eleven songs Metallica deemed worthy of inclusion here are dishearteningly unsure of themselves. St Anger was the first of the band’s albums to be released after the advent of the nu-metal movement, and the decision not to include a single lead guitar solo from Kirk Hammett – and bear in mind that the musician’s often untouchable leads had featured as a part of all but one of the original compositions the group had recorded up to that point – is without doubt the worst the band has ever made.

Musically disadvantageous, worse yet was the possibility that in eschewing Hammett’s squalling solos Metallica felt they were aligning themselves with a group such as the wildly inventive System of a Down (at the time the most popular of the new breed as well as the metal equivalent of Frank Zappa) and thus making themselves more ‘relevant’.

But a surfeit of solos was not St Anger’s only lousy idea. Metallica had decided they would write their lyrics by committee, with each member of the band suggesting couplets and ideas. Whereas in the past words written by James Hetfield, and guarded with a psychotic vigilance, were the only aspect of Metallica’s output that improved from album to album, here the group’s ‘talents’ combined to offer up one of the worst lyrical excursions of the twenty-first century. ‘These are the legs in circles run,’ sang Hetfield, apparently not at all concerned that what he was attempting to communicate made no sense at all. With a lack of artistry that is actually appalling, he adds that ‘these are the lips that taste no freedom’ – mud in the eye of those who thought it was the tongue that did the tasting – and ‘this is the feel that’s not so safe.’

As the bloated corpse of St Anger lay cold on the slab, Lars Ulrich would go only so far in responding to what was by now a clamour of criticism. To the charge that this was Metallica’s worst album to date he would admit that while ‘some people may think [that]’, he declined to ‘rank [the band’s releases] from best to worst’.

‘That kind of simplicity just doesn’t exist for me,’ he obfuscated. ‘If I was fourteen, I could probably do it. [But] now the way I see the world [it is] nothing but greys, mainly.’

Ulrich would go on to admit that during the recording process the musicians has consciously eschewed editing of any kind while deliberately pursuing a drum sound that was persistent to the point of being unbearable. As listeners wondered if all of this added up to an insult, the Dane happened upon the real motivation for St Anger. For the first time, the making of an album didn’t seem to be a musical pursuit at all, but rather an exercise in catharsis. And as with all the band’s recordings, the considerations of anyone other than themselves were simply irrelevant. Whether or not a character trait that in the past had been the group’s greatest strength could suddenly become their gravest weakness is a point well worth considering.

‘I’m the biggest Metallica fan, you’ve got to remember that,’ said the drummer. ‘Once again, as we’ve been known to do, once in a while these boundaries have to be fucked with and it was really important for us in the wake of all that stuff we had to deal with in ’01, ’02 and ’03 to take everything that we knew and rip it to bits. Just throw it up in the air and see where the pieces landed. The pieces landed [where they did] so that was what we had to do for our own sanity. I’m really proud of the fact that we did that. I still think there are some pretty great songs, or near great songs, buried in there, but I understand that for a large majority of people it’s difficult to get beyond the sonics of it. And I’m okay with that.’

Lars Ulrich would have to be, because the time had come for Metallica to take an album that no one liked and drag it around the arenas and stadiums of the world.