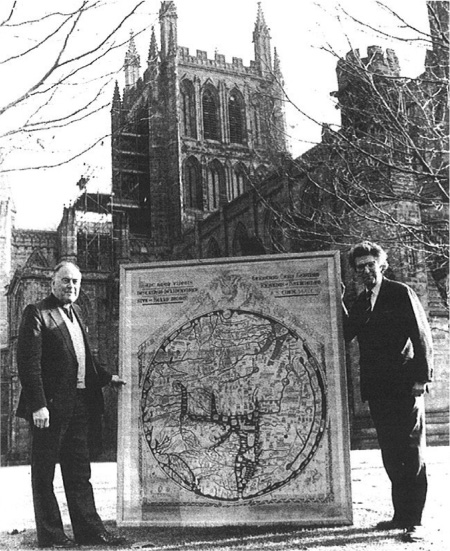

On Wednesday 16 November 1988, the Dean of Hereford, the Very Reverend Peter Haynes, and Lord Gowrie, a former Arts Minister who was now Chairman of Sotheby’s, stood outside Hereford Cathedral in suits and posed for photographs beside a framed facsimile of a large brown map. The map, almost as tall as the pair holding it, was due to be auctioned the following June, and Sotheby’s had agreed a reserve price of £3.5m, which would make it the most valuable map in the world. Later that day it would be described by Dr Christopher de Hamel, Sotheby’s expert on medieval manuscripts, as ‘without parallel the most important and most celebrated medieval map in any form.’

Lord Gowrie regretted that such an important object might soon be leaving the country to the highest bidder, but said that all attempts to save it for the nation had failed. He had been trying for almost a year to keep the map in the UK, but now needs must. The Dean explained that his eleventh-century cathedral, one of the most impressive Norman constructions in England, was in need of £7m to prevent it from crumbling to the tiled floor, and disposing of the map was the only way forward. After their announcement, the two men handed the frame to the cathedral staff, and departed, Gowrie back to London, the Dean back to his troubled place of worship.

Mass unhappiness ensued.

b b b

The map in question was Hereford’s Mappa Mundi, c.1290, and it wasn’t a beautiful thing to look at. A large shank of tough hide – measuring 163 cm by 137 cm – it has a murky rendition of the world that, at fist sight, is hard to fathom with its faded colours and indistinct lettering. It is also a map that if you had been transported from the Great Library at the time of Ptolemy, would have come as quite a surprise. Gone is the careful science of coordinates and gridlines, longtitude and latitude. And in their place is, essentially, a morality painting, a map of the world that reveals the fears and obsessions of the age. Jerusalem stands at its centre, Paradise and Purgatory at its extremes, and legendary creatures and monsters populate the faraway climes.

And this is very much its conception. The mappa (the word meant cloth or napkin rather than map in medieval times) had a lofty ambition of metaphysical meaning: a map-guide, for a largely illiterate public, to a Christian life. It has no reservation in mixing the geography of the earthly world with the ideology of the next. Its apex displays a graphic representation of the end of the world, with a Last Judgement showing, on one side, Christ and his angels beckoning towards Paradise, and on the other the devil and dragon summoning to another place.

But it seems likely that those who saw it first at the end of the thirteenth century would have done what we do now and looked for the ‘You Are Here’ spot. If so, they would have found themselves in the south-west region of the giant circle, with Hereford one of the few places mentioned in England, and England itself a fairly insignificant part of the global story. Around them is a world crowded with cities, rivers and countries teeming with human activity and strange beasts. Ancient and brilliant cartographic theories have been replaced by something else: the map as story, the map as life.

A scandal in the making: Hereford Cathedral’s Dean, Peter Haynes (left), and Sotheby’s chairman Lord Gowrie announce the sale of the Mappa Mundi.

Such a thing had never required a reserve price in an auction catalogue before. But now, according to God’s current earthly representatives, a judgement had to be made. The timing of this can be fixed precisely, to February 1986, when an expert in medieval artefacts from Sotheby’s arrived at the cathedral to appraise its most prized possessions. At the time the Mappa Mundi was not on Hereford’s sale list. The cathedral’s great treasure was thought to be the books and manuscripts of its Chained Library, a collection of theological works secured by chains to their cases to enable study but not theft. While ascending a winding stone staircase to the library, the assessor saw the dimly lit Mappa Mundi below, and asked how much it was insured for. He was astonished at the answer: £5,000. He suggested it might be worth a little more.

The furore that ensued once the sale was announced took the cathedral entirely by surprise. Britain’s National Heritage Memorial Fund expressed ‘outrage that one of the most important documents in the world is to be put into an auction room’; the British Library complained that it had not been consulted on a possible sale (though Lord Gowrie claimed that it was ‘talking rot’). The Times composed a leader that concluded: ‘The Mappa ought to remain in England, on public display, and preferably in Hereford. Its ancient and original link with that city is part of the Mappa’s identity. As a work of art, it gains from being in Hereford. It is, so to speak, the only proper frame for it.’

The following day, amid resignations from the Hereford Cathedral’s fundraising committee, several offers of a private purchase emerged, meeting the £3.5m reserve. But Canon John Tiller, the cathedral chancellor, announced that the auction would proceed regardless to gain the best possible price: ‘Our first priority is the future of the Cathedral.’

Other funding schemes were raised but came to nothing. Then some months later came one that stuck: the Mappa Mundi Trust was established with a £1m donation from Paul Getty and £2m from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, amid plans for a new building to house the map, to which the public would be charged admission. And in this way the map was saved for the nation. While these plans were laid, the map was loaned to the British Library in London where it was seen by tens of thousands who had only recently been made aware of its existence.

b b b

What exactly did the British Library visitors see? They saw what pilgrims arriving in Hereford around 1290 would have seen, but with less colour, better footnotes and tighter security. The Mappa Mundi provides a masterful cartographical insight into medieval understanding and expectations. What appears at first glance like wonderful naivety is on more informed inspection an extraordinary accumulation of history, myth and philosophy as it stood at the end of the Roman Empire, with a few medieval additions.

The map is frantic – alive with activity and achievement. Once you grow accustomed to it, it is hard to pull yourself away. There are approximately 1,100 place names, figurative drawings and inscriptions, sourced from Biblical, Classical and Christian texts, from the elder Pliny, Strabo and Solinus to St Jerome and Isidore of Seville. In its distillation of geographical, historical and religious knowledge the mappa serves as an itinerary, a gazetteer, a parable, a bestiary and an educational aid. Indeed, all history is here, happening at the same time: the Tower of Babel; Noah’s Ark as it comes to rest on dry land; the Golden Fleece; the Labyrinth in Crete where the Minotaur lived. And surely for contemporaries – locals and pilgrims – it must have constituted the most arresting freakshow in town. With its parade of dung-firing animals, dog-headed or bat-eared humans, a winged sphinx with a young woman’s face, it seems closer to Hieronymus Bosch than to the scientific Greek cartographers.

These days you’d be tested for chemical substances: the Nile Delta bisects a magical world of unicorns, castles and a peculiar mandrake man.

We are about ninety years from Chaucer, and although there is much to be read on the map in clear gothic Latin and French script, most visitors to Hereford would have obtained their knowledge from the pictures. A century and a half before the printing press, these drawings – primitive and devoid of perspective, with almost every turreted building indistinguishable from the one next to it – would have been the first big storyboard they had ever seen, and its images would surely haunt their dreams.

Observed through modern eyes, the map is also a sublime puzzle. Things are not where we might expect them to be. What we regard as north lies to the left, while east is at the top, a placing that has given us the word ‘Orientation’. There are no great oceans, but instead the map is surrounded by a watery frame and floating islands of malformed creatures abound.

There are dismal transcribing errors in which Europe is labelled Affrica and Africa appears as Europa. Cities and emblematic structures seem to be selected by a curious mixture of importance, hearsay, topicality and whim: the Colossus of a misplaced Rhodes occupies more space than cities more valuable for trade or learning, such as Venice. Both Norway and Sweden appear on the map, although only Norway is named.

The British Isles appear at the northwest corner of the map, on their side, to fit the space. North-east England is populated with names, while the south-west is almost ignored. Edward I’s new castle at Caernarfon makes an appearance – only a few years after its construction began – which not only helps with the dating of the map, but also confirms that new local landmarks are judged as important as those of antiquity.

There are many further anomalies. Moses appears with horns, a familiar medieval confusion between cornu (horn) and the intended cornutus (shining). The monster Scylla (labelled Svilla) appears twice, once in the familiar pairing with the whirlpool Charybdis, and once where the Scilly Isles lie, possibly a mishearing by a scribe. And there is another story going on here, as with many mappae mundi. The wilderness – the scary stuff, the unknown lands – sends a message to the viewer about the glories of civilisation and order and (self-)control. For contemporaries, it is another Christian doctrine: follow the laid-down path. To the modern viewer, though, it is the weirdness that most enthrals: the rich, demonic and comical features, like the sciapod – a man deploying his single swollen foot to shield himself from the sun.

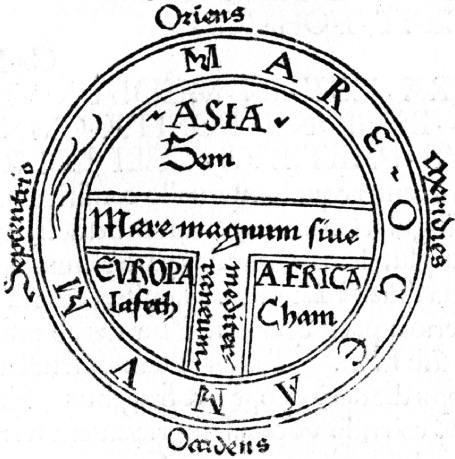

To cartographic historians, the Hereford Mappa Mundi is categorised as a ‘T-O’ (or ‘T within an O’) map. This is a form developed at the time of the Roman Emperor Agrippa (after 12 BC) and described a simple way of separating the spherical earth into three parts. The known continents of the ancient world – Asia, Europe and Africa – are divided in the middle by the horizontal Don and Danube rivers and the Aegean Sea (on the left) and the Nile (on the right) as they flow into the wide vertical Mediterranean.

The basic form of a T-O map, crudely dividing up Asia, Europe and Africa. This one is from a twelfth-century Spanish manuscript.

But the Hereford map is more than a circle. Determined to use every inch of available space on the hide, it encompasses monumental scenes above and below it. So the world is crowned by the Last Judgment, while at the base a scene on the left depicts the Emperor Augustus instructing surveyors to ‘Go into the whole world and report to the Senate on each continent.’ A scene to the right of this is less obvious – and may perhaps be the map’s equivalent of the ‘and this just in…’ news bulletin. It shows a horseman and hunter in conversation, the message (in French rather than the map’s general use of Latin) being ‘Go ahead’. Who these figures are is unclear; one interpretation has them as the subject of a court case over hunting rights that took place in Hereford as the map was drawn.

In the January 1955 edition of the English periodical Notes and Queries, a scholar called Malcolm Letts analysed the more vivid drawings on the map, and divined their meaning. Letts was easily shocked, but his breathless prose has never been bettered in conveying sheer wonder. He describes the exploits of gold-digging ants in great detail, and devotes a whole paragraph to a salamander. He admires a picture of the Gangines ‘busily collecting fruit from a tree. These creatures were said to live on the smell of apples which they always carried about with them, otherwise … they died anon.’ Close by ‘comes the lynx whose urine congealed itself into the hardness of a stone (most vividly presented by the artist.)’ Then, in the centre of the map, near Phrygia, he sees the Bonacon, ‘whose method of defence was to discharge its ordure over three acres of ground and set fire to everything within reach. The creature is shown in its customary posture of defence …’ Reviewing the drawings on the extreme right of the map, Letts observes, ‘two men embracing each other.’ They are the Garamantes of Solinus, of whom little is known ‘except that they abstained from war and disliked strangers.’

How could such a marvellous thing ever be sold to fix a leaky roof?

b b b

To meet the man who almost sold the Mappa Mundi one must drive up a hill from Hereford town centre, past vineyards, hop fields and many barns, until one eventually arrives at the beamed home of the Very Reverend Peter Haynes, who retired from his cathedral in 1992 and now spends time indulging his passion for model trains. I made this pilgrimage in the summer of 2011, to be greeted with tea, lemon cake and a slim cuttings file. The file included newspaper articles, a press release and a Mappa Mundi Plc share prospectus which didn’t quite fly.

Haynes is eighty-seven but remains Dean Emeritus of the cathedral, and when he visits each Sunday many people still address him as Mr Dean. He served in the RAF during the war, was ordained after theological college at Oxford, became Vicar of Glastonbury at the time of the first festival in 1970, moved to Wells as Archdeacon in 1974, and, after a personal request by Margaret Thatcher, took up as Dean of Hereford in 1982.

He says that the first thing he did was send copies of the cathedral accounts in confidence to an old accountant friend, the financial director of Clarks, the shoe firm. ‘He nearly had kittens. He sent them back to me and said, “You’re in for terrible trouble.”’ There had been a continuous operating deficit for years, and an overdraft at the bank of more than £150,000. ‘I realised that what the congregation was raising each year, about £17,000, and they fondly imagined was paying for the clergy, was actually going over to Lloyds Bank to service the overdraft.’

Worse was forecast: the staff pension scheme was inadequate, a building survey had revealed large and dangerous cracks, the choir required an endowment, and the cathedral’s historical treasures were inadequately cared for and poorly presented. An appeal was launched in April 1985 by the Prince and Princess of Wales, but its target of £1m to restore the fabric of the building was soon deemed inadequate. It was estimated that the cathedral needed a capital injection of £7m to secure its long term security and endowments, and so the Mappa Mundi would have to go (this would also ensure that the Chained Library would not be broken up). At the time, the Dean believed that it wouldn’t be much missed. ‘I would often welcome visitors when they came to the cathedral, just to keep my hand in. I would tell them, “Oh, there’s a very ancient map in the North Choir Aisle if you’d like to see it,” but nobody thought anything of it.’

When Haynes examined the map himself he noticed damp around the perimeter. So he contacted a man called Arthur David Baynes-Cope at the British Museum. ‘He was a world authority on mould,’ Haynes told me, although Dr Baynes-Cope, a chemist, was also an expert on paper and book conservation. Not long before he died in 2002 he said that he was particularly proud of his forensic work that had exposed Piltdown Man as a fake. ‘I got him up here,’ Haynes continued, ‘and he had a look at it, and he said, “Oh, I think I know what we can do with that.” He came up about a fortnight later, and he put this cord around the side, and I said, “What’s that then?” And he said, “Oh, this is pyjama cord from Dickins & Jones”.’

Haynes says that he supervised a great amount of other work while at the cathedral, but knows that his time there will mostly be remembered for the mappa saga. He seems not entirely unhappy with this. His eyes sparkle as he tells me of an idea they had for a share issue to raise funds: ‘At the beginning it was important that we kept it all secret. So there was a codename for it, an anagram: Madam Pin-Up.’

b b b

These days we can all buy a pretty good Mappa Mundi of our own. The copy that Peter Haynes and Lord Gowrie posed with outside the cathedral in 1988 was a lithograph from 1869, at that time the best facsimile available. But in 2010 the Folio Society brought out a spectacular version, 9/10ths in scale, which benefitted not only from digital reproduction (a phrase which too often spells the death of art), but also from the imagination and learning of twenty-first-century experts, including Peter Barber, the head of maps at the British Library and a trustee of Hereford’s Mappa Mundi. The map was not only visually crisped up, but rendered with vivid colours thought to be close to the original – lustrous reds, blues, greens and golds. It was printed on a vellum-like material called Neobond, mounted on canvas, topped and tailed by wooden struts of Hereford oak, and accompanied by erudite essays; limited to an edition of 1,000, it would set you back £745.

Academic study of the Mappa Mundi has had a resurgence of late – another benign result of the abortive sale – and now tends towards the investigative and forensic rather than the interpretive. But many fundamental questions remain definitively unanswered, such as exactly who made it.

You probably don’t want to live here: the Bonacon spreads his ‘ordure’.

The left-hand corner reveals the main clue. There is a plea to all those who ‘hear, read or see’ the map to pray for ‘Richard de Haldingham e Lafford’ who ‘made and laid it out’. The place names can be transposed to Holdingham and Sleaford in Lincolnshire, but who was this man, and what did he ‘make’ exactly? In 1999, a symposium in Hereford attracted the leading Mappa Mundi scholars, most of whom agreed upon the hand of a man called Richard of Battle, known in Latin as Richard de Bello, a canon of Lincoln and Salisbury, a prebendary of Sleaford who may have lived in Holdingham; but they were unsure if this was one man, or a Richard of Battle Snr and Jnr, related or not.

Four years later, the map historian Dan Terkla presented a paper on the Mappa Mundi at the twentieth International Conference on the History of Cartography at Harvard. He speculated that four separate men were directly responsible for the map’s design, three of them named Richard – Richard of Haldingham and Lafford, Richard de Bello, Richard Swinfield – and the other, Thomas de Cantilupe. The second Richard, he believes, was a younger relation of the first, who worked on the map at Hereford after moving from Lincoln; the third was a friend working as a financial administrator and bishop at the cathedral; while Thomas de Cantilupe was Swinfield’s predecessor and may also have been the mounted huntsman on the map’s fringe.

Terkla asserted that the map formed a part of what he called the Cantilupe Pilgrimage Complex, a collection of possessions and relics associated with the bishop, who was canonised in 1320. De Cantilupe’s shrine in the north transept had proved a huge draw on the pilgrim trail even before his sainthood, after word spread of its uncanny associations with miracles. Almost five hundred miraculous acts were recorded by the custodians of the shrine between 1287 and 1312, with seventy-one miracles listed in April 1287 alone – the year the royal family visited.

In 2000, a rather different Mappa Mundi scholar, Scott D. Westrem, travelled from the United States to examine the map without the glass, and his forensic report displays Sherlockian sleuthing. ‘The vellum on which it was drawn came from the hide of a single calf, probably less than one year old when it was slaughtered,’ he surmised. He observed that the map was drawn on the inner side of the skin, noting the silvery fleshy membrane. He described how the cured hide was carefully scraped to remove hair and residual fat, and suggested that the skinner’s knife slipped only once during the process, severing the skin near the tail end, probably when it encountered scar tissue. ‘The skin’s quality is very high and apparently of even thickness; there is almost no sign of the rippling that results from the impression of the rib cage and other bones, indicating that the beast was consistently well fed.’

b b b

In May 2011, Dominic Harbour, the cathedral’s commercial director, is taking another pair of visitors around the Mappa Mundi. I’m one of them. Two weeks before, the map had been installed in a new frame, something that has brought it about a foot down the wall so that Jerusalem now coincides with most people’s eye level. ‘Before, it was presented within a space in an architectural way,’ Harbour explains. ‘But people relate to it in an ergonomic way. It needs to be related to your height and what you can see and what you can touch.’

The touching is important. Although not actively encouraged, visitors are not reprimanded for doing what comes naturally – putting their fingers to the glass as a primitive way of navigating around it. At the end of each day, the glass is cleaned of fingerprints, and there are some marks over Jerusalem, and others over Europe, reflecting the origin of that day’s visitors. Americans keep their fingers to themselves. But the greasiest spot on the glass is around Hereford. ‘The fingerprints tell exactly the same story they did when the map was new,’ Harbour says. ‘For a long time people thought that “Hereford” had been added to the map after it was originally made, suggesting that it may have begun life elsewhere. Now the thinking is that Hereford was indeed added to it later, but only after the original inscription of Hereford had been worn away from people touching it.’

Harbour is in his late-thirties, and has been working with the map since he was twenty-two. He arrived fresh from art college in 1991, helped design an explanatory booklet and a facsimile map with an English translation, and soon realised that his six-month contract might have to be extended. He began thinking about how the map could be presented in a more cohesive and effective way, and helped plan its current, impressive new exhibition space in a cathedral cloister, designed to accommodate both the Mappa Mundi and the Chained Library. The space, completed in 1996, is essentially a glorified lean-to, albeit a lean-to where a fifteenth-century stone wall adjoins an eleventh-century one.

Harbour takes his visitors to the spots where the map has been displayed or concealed through the centuries – the Lady Chapel, various transepts, the vestry where it lay under floorboards. He says he once drew a map of the map’s movements, and ‘ended up with scribbles all over the place’. He recalls that when he was first taken to see the map, at the age of eight, he saw ‘this really strange brown thing in a case, otherworldly, magical, like some scientific sample in a jar. I don’t think it was explained at all, or at least nothing that was accessible to me. Just, “This is Mappa Mundi and it is very important.”’

As we look at the map together, I find myself nodding as Harbour suggests that ‘it is still delivering new things’. No modern traveller can look at it and not feel desire. It is one of the most appealing features of large maps, and world maps in particular, that all journeys are feasible. On the Hereford map, everywhere except Paradise seems reachable in sturdy vessels, and even the fiercest beasts look biddable. And then it struck me: in 1290, unlike today, there seemed to be little left to explore, and no great wilderness or sea to detain you long. Unfathomable sea monsters and great white polar silences only came later. The simple message here is: we’ve done our work in this place, for the inhabitable world is laid down on the back of a calf. So what remains for us mere mortals? Only miracles, a higher calling, and things forever beyond our grasp. Spread the word, pilgrims.

These days we employ the term ‘road map’ as a political phrase, to denote the prospect of progress. A situation may seem hopeless, but at least we have a plan: if we get to staging post A, we then have a chance of getting to staging post B. Of course, the phrase is occasionally used by people not going anywhere, notably, in 2002, by George Bush, Tony Blair and others engaged in the Middle East peace process.

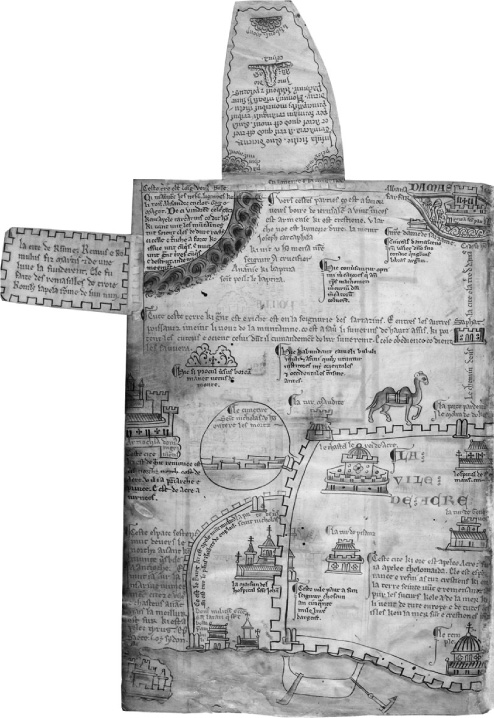

Back in the thirteenth century, a few decades before the Mappa Mundi was created, a monk called Matthew Paris (c.1200–59) was involved in constructing an authentic road map to the Middle East – a map, in fact, that ended at Jerusalem, then under relatively benign Muslim rule and attracting large numbers of Christian pilgrims.

As part of his monastic duties, Paris worked as a manuscript illuminator and historian in the abbey at St Albans, north of London. The abbey possessed the attributes of an early university and Paris was keen to distil his learning in both visual and textual form. The result was his Chronica Majora, an ambitious history of the world from the Creation to the present. Writing in Old French and Latin, Paris combined the work of Roger Wendover, an immediate predecessor at St Albans, with his own experience. This included his own extensive travels in Europe and visits to the court of Henry III, as well as the stories gleaned from visitors to his own abbey.

Jerusalem this way (or maybe that …). Matthew Paris’s interactive road map suggests several ways to salvation.

His strip map from London to Jerusalem occupies seven pages of vellum at the beginning of his Chronica Majora and is an enchanting manuscript, full of little diversions and side-panels to keep its readers entertained, with glued-on pop-up leaves extending a journey or explanation over or round a page. One flap attached to the top of a page features Sicily and Mount Etna, described as the Mouth of Hell. Interactivity went further still, as the viewer was often presented with a choice of alternative routes, heading through France and Italy at different angles. Was this the first map with movable parts? It was certainly the first route map that we know of with such a laissez-faire attitude to the actual route.

Paris’s readers may not have been particularly attracted to the prospect of actually embarking upon the itinerary laid before them (quite probably the reverse), but they would have revelled in the imagined, spiritual journey – the virtual crusade. And they would have been engaged, as we are still, with its pictorial evocation of the route.

But the map is significant for another reason. Paris refers to it as an ‘itinerary’, and it is where we get the word journey, from the Old French jornee or jurnee, the estimate of a reasonable ‘day’s travel’ on a mule. The word appears between many destinations on Paris’s map, and on one occasion, with nothing else of importance en route, it is stretched out for dynamic effect into ‘ju-r-r-r-n-ee’.

Each page, which has two columns and flows from bottom to top and left to right, contains about a week’s expedition. We begin in London, displayed as a walled city with the ‘River de Tamise’, ‘Audgate’ and ‘Billingesgate’ marked against a selection of crenellated buildings and steeples, dominated by St Paul’s. From there it’s a day to Rochester, another day to Canterbury, one more to Dover and northern France before heading through Reims, Chambery, and Rome. The map’s accuracy declines as Paris leaves Paris, but to criticise the appearance of Fleury as coming just after Chanceaux rather than just after Paris would be to misjudge the map’s intentions; it was clearer, for the narrative of the story, to have the site of Saint Benedict’s bones there rather than earlier.

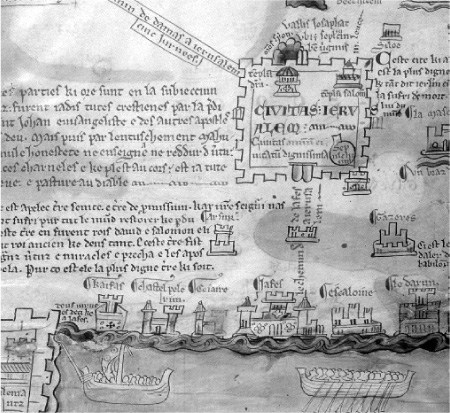

Another entry, on another flap, suggests a certain weariness with the map-making craft: ‘Toward the Sea of Venice and toward Constantinople on this coast,’ Paris writes, ‘are these cities which are so far away.’ But the strip eventually reaches Jerusalem, the final destination, which Paris depicts with the Dome of the Rock and church of the Holy Sepulchre, and a reasonably coherent coastline, from the gateway port of Acre, and beyond it, Bethlehem.

Are we there yet? Jerusalem finally in view as we near the end of the journey.

Paris does seem to have been troubled by problems of scale. On another map, one of four he drew of Britain, he writes regretfully (across an illustration of London) that ‘If the page had allowed it, this whole island would have been longer,’ which is not necessarily the ideal cartographic lesson to pass on to impressionable minds. Despite the squeeze, Scotland is permitted a generous and bulbous display, a rarity in this period. But Paris also produced another map in which Britain has uncannily accurate proportions, not least in Wales and the West Country, and it is difficult to argue with the British Library’s claims that it is the earliest surviving map of the country with such a high level of detail.

One other significant Paris strip map has also survived, from London to Apulia, but it is less elaborate than the Jerusalem version and crammed onto one page of his Book Of Additions, an addenda to his larger history that contains such oddities as a map of the main Roman roads with Dunstable at the centre and a map of the world’s leading winds (with the earth at the centre).

With all these maps, Matthew Paris achieved one other thing easily overlooked by detailed cartographic analysis: some fifty years before the Hereford Mappa Mundi, he made objects that provided a highly engaging and unique viewing experience, and he was uncommonly prescient in showing how maps may delight by their beauty and intrigue. His maps nourish the imagination, and they prompt interaction and engagement. They have an uncanny resemblance to the maps we draw as children.