‘It’s all about a map, and a treasure …’

Robert Louis Stevenson, describing his new book, 1881

Why would anyone ever go to Trinidad? That’s Trinidad out in the southern Atlantic, one of six islands in a barren archipelago, rather than the sandy white Caribbean Trinidad honeyeymoon isle, or the Trinidad in Colombia, Cuba or Paraguay, or even the Trinidads in California, Texas or Washington. All these places may have their charms.

But our Trinidad lies somewhere else. It is a place where even the most experienced sailors struggle among treacherous reefs to negotiate a landing, and, failing to do so, gratefully turn back. It is a place where sea birds attack from the air and armies of crabs attack on land. The island boasts little edible vegetation, but it does offer an angry volcano and sharks at its rim. In 1881, the British adventurer E.F. Knight called the place ‘one of the most uncanny and dispiriting spots on earth’, and vowed never to return.

But what if you came across a map of Trinidad with details of buried treasure – the genuine ‘X marks the spot’ variety, where the value of X makes the tomb of Tutankhamun look like a disappointing evening’s metal detection on Clacton Sands. Then wouldn’t you be romantic and greedy enough to take up the challenge?

You wouldn’t be alone. In 1889, the same Edward Frederick Knight who vowed never to return, returned. Lured by the prospect of shiny wonders from Lima (giant gold candlesticks, jewel-rimmed chalices, chests of coins, gold and silver plate), he was equally attracted by the dangerous narrative that piratical legend confers. He not only believed the treasure was there, but that divine intervention had selected him to locate it. God had wanted him to go there, he believed, because God had given him a map.

In The Cruise of the Alerte, the vivid and (one imagines) true account of his quest published in 1890, Knight explained that he had not known of the existence of treasure on Trinidad when he had first approached the island eight years earlier. On that trip, he had been yachting around the South Atlantic and South America with a small crew, and on a journey from Montevideo to Bahia faced unexpectedly strong headwinds. Steering eastward, he was about 700 miles from the east coast of Brazil when he first saw Trinidad, latitude 20° 30˙ south, longitude 29° 22˙ west. He decided to land, struggled desperately with the coral reefs, spent nine ghastly days there, and found the land crabs ‘hideous’.

Four years after returning to England (he was a successful though presumably rather unsatisfied barrister) Knight read in a newspaper that a ship called the Aurea was leaving the Tyne bound for Trinidad with a skilled and determined crew aboard, and many digging tools. They were hunting for buried treasure, but were unsuccessful. Knight thought little more of this until three years later, when he heard that a few Tynesiders were planning to have another crack at the loot. He travelled to South Shields, found one of the men from the Aurea, and was told the following tale.

There was a retired sea captain living in Newcastle known, for the purposes of the story, as Captain P. He had been involved in the opium trade in the late-1840s, and on one of his voyages had enlisted a quartermaster known as The Pirate, so called because of a scar across his cheek. The Pirate was probably a Russian Finn, and had so impressed Captain P with his navigational skills that the two became friends. When The Pirate was struck with dysentery on a trip from China to Bombay, Captain P gave him special care, but there was little to be done – the man was dying. Nearing the end in a hospital in Bombay, The Pirate wanted to repay the captain for his care, and said he wished to reveal a secret. But first the captain would have to close the ward door. Having done so, The Pirate directed his visitor to a chest, and asked him to remove a parcel. It contained a piece of tarpaulin, and on the tarpaulin there was a treasure map of Trinidad.

The spot marked X lay in the shadow of Sugarloaf Mountain. Much of the bounty had come from Lima Cathedral when it was plundered during the war of independence. The Pirate had heard about it because he was indeed a pirate, the only survivor from a trip to Trinidad to bury the treasure in 1821. He had been unable to return since that date, and he believed all his fellow pirates had been captured and executed. He was certain that the loot was still many feet beneath the sand and rock.

As tall tales go, this was a whopper. In 1911, the American author Ralph D. Paine undertook a survey of ‘the gold, jewels and plate of pirates, galleons etc, which are sought for to this day’, culminating in ‘The Book of Buried Treasure’. He found one strikingly common trait. There was always a lone survivor of a piratical crew, and he, ‘having somehow escaped the hanging, shooting or drowning that he handsomely merited, preserved a chart showing where the treasure had been hid. Unable to return to the place, he gave the parchment to some friend or shipmate, this dramatic transfer usually happening as a death-bed ceremony.’ The recipient would then dig in vain, ‘heartily damning the departed pirate for his misleading landmarks and bearings,’ before handing down the map, and the gried, to the next generation.

m m m

Two years before Knight embarked on his own adventure, another account of buried treasure took hold on the popular imagination. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, serialised in 1881 and then published as a book two years later, told the story of untold wealth on a far-flung isle, and a pirate’s chest containing a mysterious oilskin. The oilskin contained two things, a logbook and a sealed paper, with the latter, according to the book’s young narrator Jim Hawkins, showing ‘the map of an island, with latitude and longitude, soundings, names of hills and bays and inlets, and every particular that would be needed to bring a ship to safe anchorage upon its shores.’ The buried treasure was the property of the murderous Captain Flint, who, although dead when the book begins, had drawn instructions to help others locate it.

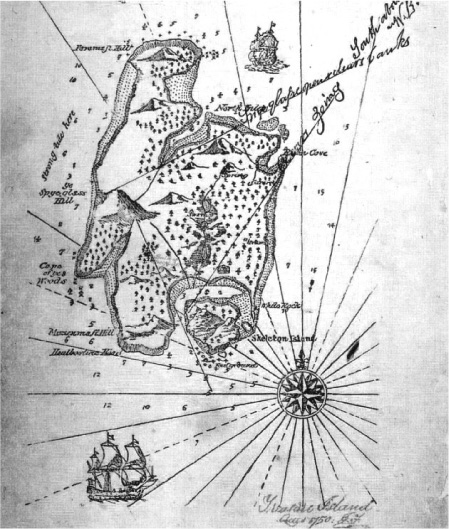

Treasure Island was about nine miles long and five across, and shaped ‘like a fat dragon standing up’. It contained a central hill called ‘The Spye-glass’, and three red crosses, one of them accompanied by the words ‘bulk of treasure here.’ And so off they went, Jim Hawkins and his buccaneer friends, towards skulduggery and terrible betrayals, and a hoard worth £700,000. The map that accompanies the book, the most famous in all fiction alongside Tolkien’s Middle Earth, was drawn by RSL himself and dated 1750. It is crowned by an illustration of two mermaids displaying the scale, while two galleons patrol the coasts.

Its origins are uncertain. Stevenson wrote the bulk of the book at the tail-end of a wet summer in the Scottish highlands, and among his fellow holidaymakers was one Lloyd Osbourne, his newly acquired twelve-year-old stepson. Osbourne later recalled a day when he ‘happened to be tinting a map of an island I had drawn. Stevenson came in as I was finishing it, and with his affectionate interest in everything I was doing, leaned over my shoulder, and was soon elaborating the map and naming it. I shall never forget the thrill of Skeleton Island, Spyglass Hill, nor the heart-stirring climax of the three red crosses!’

Irresistible – Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island.

Osbourne also remembers Stevenson writing the words ‘Treasure Island’ in the map’s top right-hand corner. ‘And he seemed to know so much about it too – the pirates, the buried treasure, the man who had been marooned on the island.’ In what he recalls as ‘a heaven of enchantment,’ Osbourne then exclaimed ‘Oh, for a story about it!’

Whether the story was already underway, or whether this map was the inspiration for the thirty-one-year-old Stevenson’s first complete book (and who wouldn’t claim to be the spark for one of the classics of world literature?), remains the subject of conjecture. Looking back at his creation for an article in The Idler magazine years later, Stevenson wrote of the enthusiasm of his stepson for the early drafts of his work as it appeared in early serialised form in Young Folks magazine, but he claimed the map as his own work. ‘I made the map of an island. It was (I thought) beautifully coloured; the shape of it took my fancy beyond expression; it contained harbours that pleased me like sonnets …’ He also claimed it drove the plot: once he had constructed a place called Skeleton Hill, ‘not knowing what I meant’, and placed it at the south-east corner, he then directed the narrative around it.

Stevenson had created a moral fable of venality, vice and some virtue. Treasure Island is a coming-of-age story, and its obsession with disease and disability mirrors Stevenson’s own battle with illness from childhood. Its swashbuckling narrative is also a rebellion against the high-Scottish moralising that almost suffocated its author in his youth. The book defined our communal mental vision of piracy, parrots, peg-legs, rum rations, and mutiny with Bristolian accents, and the treasure map within it not only drives the plot but stealthily does something else: it forms the basis of how we imagine treasure maps to this day – ragged, mischievous, curling and foxed, with not quite enough information to make those who hold it sure of their course, yet just enough to fire up a life-defining quest.

In 1894 Stevenson wrote that all authors needed a map: ‘Better if the country be real, and he has walked every foot of it and knows every milestone. But even with imaginary places, he will do well in the beginning to provide a map; as he studies it, relations will appear that he had not thought upon; he will discover obvious, though unsuspected, short cuts and footprints for his messengers; and even when a map is not all the plot, as it was in Treasure Island, it will be found to be a mine of suggestion.’

m m m

Maps in our minds are powerful things, and those we see as children may never leave us. We may already know the shape of E.F. Knight’s Trinidad, as it was a model for Arthur Ransome’s fictional Crab Island in Peter Duck, the third of his Swallows and Amazons adventures, published in 1932.

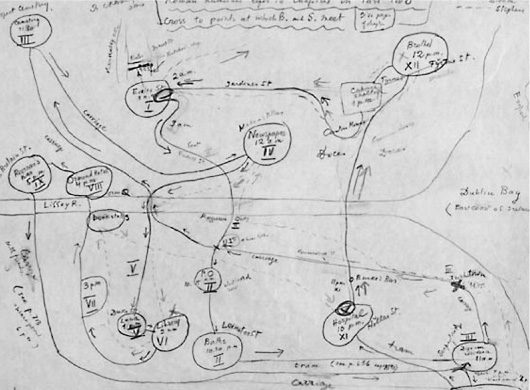

So that’s left at Davy Byrne’s Pub. Nabokov plots Bloom’s Dublin ramblings in Ulysses.

Five years later, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, another trail of treasure, was published with a map as its endpapers, and maps became a crucial feature of his Lord of the Rings trilogy. In fact, Tolkien’s maps are probably the most influential in modern popular culture, having spawned, over the past couple of decades, a whole genre and generation of fantasy books, maps and games; they continue to wield a heavy influence over computer gamers.

Beyond children’s fiction, a book’s journey may inspire maps where none were intended – impossible ones such as Sir Thomas More’s Utopia, or ones such as Nabokov’s map of the journeys through Dublin of Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom in Ulysses which he hoped would help engage his students. James Joyce once claimed that his novel was itself a practical map: if Dublin ‘suddenly disappeared from the earth, it could be reconstructed from my book.’

m m m

A treasure map is the earliest form of map we have. They began appearing on cave walls in the Paleolithic age (take your spear to this place, a chalky arrow directs, and a woolly creature will be yours), and they surround us still, most often in disruptive digital form (click here, lucky competition winner, and you will be led astray). As a child we encounter them in literature, board games and easter egg hunts, and at school we learn how to fabricate them with coffee grounds to age the edges. As an adult, more of the same: intricately planned dives persist on Pacific coasts where galleons once spilled doubloons, albeit with sonar replacing the leathery chart. We like a puzzle and we like reward, and a treasure map, with its alluring powers to guide, reveal, perplex and make you instantly stinking rich, satisfies fundamental human needs.

If this appears fanciful, examine the archive of treasure maps in the Washington DC’s Library of Congress. This contains a detailed list of a hundred-odd guides and nautical charts. It includes the official wreck chart from the New Zealand Marine Department showing twenty-five coastal wrecks between April 1885 and March 1886; and a list of 147 wrecks in the Great Lakes between 1886 and 1891, with descriptions of sunken vessels, approximate location of sinking, and value of unrecovered cargo.

Others are more romantic. There is a ‘map of famous pirates, buccaneers & freebooters who roamed the seas during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries … from the coast of Central America east to Ceylon’. Or a ‘charte of olde Choctawhatchee Bay and Camp Walton, showing those alleged locations of the buried & sunken pyrate booty of Captain Billy Bowlegs, a freebooter, as well as the lost treasures, sunken ships and riches of sundry other pyrates and sea rovers believed to have frequented these waters.’

This latter map, with details of treasure buried between 1700 and 1955, was published in 1956 and was available from ‘Mr Titler, Wayside Miss, $1.00 postpaid.’ But the key supplier is clearly one Ferris La Verne Coffman, who not only sold individual treasure maps of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, but also constructed an Atlas of Treasure Maps, containing 41 different spreads of the Western Hemisphere with 42,000 crosses for sunken and buried treasure. ‘Of these I have been able to authenticate about 3,500,’ the indefatigable Mrs Coffman claimed. Yours direct from the explorer, $10.

The catalogue of these maps comes with a slightly comic cautionary foreword from Walter W. Ristow, Chief of the Library of Congress Map Division: ‘The Library assumes no responsibility for the accuracy or inaccuracy of the maps, and offers no guarantee that all who consult them will find tangible riches.’ He explains that maps should be their own reward, a pleasure beyond greed.

Robert Louis Stevenson loved not only treasure maps, but maps in general. He liked the idea of a map, and the feel of its folds in his hands. He liked the naming of maps, and the fact that a map could get you home but also get you lost. And he liked the fact that it would take him to places he had never been before, in reality or in his head. ‘I am told there are people who do not care for maps, and find it hard to believe,’ he wrote in My First Book in 1894, his account of the inspirations for Treasure Island. What else did he like about maps? ‘The names, the shapes of the woodlands, the courses of the roads and rivers, the prehistoric footsteps of man still distinctly traceable up hill and down dale, the mills and the ruins, the ponds and the ferries, perhaps the Standing Stone or the Druidic Circle on the heath; here is an inexhaustible fund of interest for any man with eyes to see or twopenceworth of imagination to understand with!’

An odd thing about the map of Treasure Island is that it is not the one that he consulted when he wrote his book. The original sketch was forever lost in transit between a post office in Scotland and his London publishers Cassell. ‘The proofs came,’ Stevenson recalled, ‘they were corrected, but I heard nothing of the map. I wrote and asked; was told it had never been received, and sat aghast.’ So he redrew it, finding the experience both dispiriting and mechanical. ‘It is one thing to draw a map at random … and write up a story to the measurements. It is quite another to have to examine a whole book, make an inventory of all the allusions contained in it, and, with a pair of compasses, painfully design a map to suit the data.’ What he was describing here was, of course, the horror facing all students of real-world cartography. He did manage it, and produced the map we have today. His father helped by adding the sailing directions of Billy Bones and forging the signature of Captain Flint. ‘But somehow it was never Treasure Island.’

The map he left us resembles the basic shape of Scotland, or at least the shape of Scotland as he knew it to exist in the eighteenth century. But its minuscule size and random details – coves, rocks, hills, forests and ‘strong tide here’ – suggest a more precise inspiration. One of the sparks may have come from the small island in a pond in Queen Street Gardens, Edinburgh, where Stevenson played as a child. Another may have been Unst in the Shetlands, Britain’s most northerly inhabited island, close to the spot where his uncle David Stevenson built the lighthouse at Muckle Flugga in the 1850s to guide British naval convoys safely on their way to the Crimea. But it could have really been any treacherous region off the Scottish coast: his family formed the engineering dynasty known as the Lighthouse Stevensons, and had taken Robert on several stormy trips to inspect their creations. He himself had trained as a marine engineer before his poor health suggested a more sedentary career.

Moreover, Stevenson’s engagement with maps was evidently an hereditary affair. Not long after his grandfather Robert Stevenson had constructed the monumental Bell Rock lighthouse off the coast of Arbroath in 1810, he published an ‘Account’ of his achievement, along with a map of the lighthouse and its surrounding area of rock (also known as Inchcape, and wholly visible only at low tide). Like a conquistador of old, Stevenson Snr was free to identify and name places on the map as he wished, plotting its narrative story much as his grandson would later plot his novels.

So there was Gray’s Rock, Cuningham’s Ledge, Rattray’s Ledge and Hope Wharf – and nearby were Duff’s Wharf, Port Boyle and The Abbotsford. There were almost seventy names in all, with every pool, promontory and outcrop christened, mostly with the surnames of those involved in the lighthouse’s construction. However, Scoresby’s Point was named after Stevenson’s explorer friend Captain William Scoresby Jnr, who opened up the Arctic, and on the south-western extremity, Sir Ralph The Rover’s Ledge is named after the pirate who once may have carried away the rock’s alarm bell. And scattered around the main rock lie other rocks, less visible but equally treacherous, which Stevenson was careful to name after meddlesome lawyers and civil servants.

Mapping in the family: Robert Stevenson Snr litters the Bell Rock lighthouse with treacherous rocks named after lawyers.

m m m

If any of this was known to Edward Frederick Knight in 1885 when he first heard of the Trinidadian treasure, he made no mention of it as he assembled a crew for his own voyage, took along the same map that the Aurea sailors had obtained (a copy of the map from Captain P, detailing the shape of the island, where best to land, and where the treasure lay), and set off in his 64-foot teak boat with 600 gallons of water, four sailing professionals and nine ‘gentleman adventurers’ each paying £100 for the privilege.

And why would we, as latterday readers, not wish him well? As Ralph Paine wrote two decades later, ‘to be over critical of buried treasure stories … is to clip the spirit of adventure to a pedestrian gait … The base iconoclast may perhaps demolish Santa Claus, but industrious dreamers will be digging for the gold of Captain Kidd long after the last stocking shall have been pinned above the fireplace.’

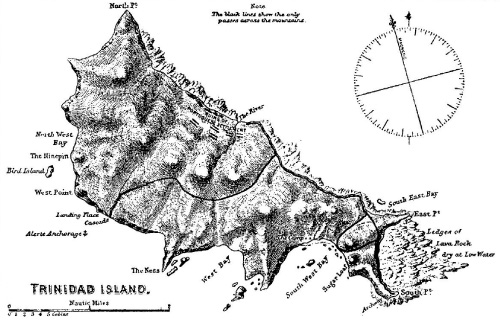

The fantasy buccaneers of Stevenson’s Treasure Island find their hopes dashed; someone had dug up the gold before them. E.F. Knight and his colleagues on the Alerte spent three long months on Trinidad in the winter of 1889, most of it spent digging. The map of the island that accompanied his published account the following year does indeed look like a challenging place, craggy from the coast and almost wholly mountainous on land. Along the entire northern and eastern shoreline are marked layers of lava rock ledges. There are no place names on land, but many on its shoreline: the Ninepin, West Point, The Ness, Sugar Loaf, East and North Point. Knight’s anchorage for the Alerte is marked to the west, more than two nautical miles from the crew’s camp on land, which was another half-mile from the digging site in the shadow of Sugar Loaf. The map is bisected by a red line marking the only passage through the mountains.

Knight’s map of Trinidad from his book, The Cruise of the Alerte.

Knight had brought with him a drill, a hydraulic lift, many guns, several wheelbarrows, crow bars and shovels for every man, and with these tools they worked at the rock and earth, initially with optimism and finally with desperation. They had landed with difficulty, found the island quite as foreboding as they had anticipated, loathed the sun, erected fences to ward off the land crabs, and complained of ‘a wreath of dense vapour’ even on the clearest day.

But all would be worth it if they returned rich. The map led them not only to the ravine and remains of a craggy cairn where they were instructed to dig, but also to the rusting tools abandoned after previous attempts. As they dug, fragments of wreckage from stranded ships washed about them. They made trenches, cracked rocks, and began to resemble savages in their torn clothes and roasted skin. After three months they abandoned their quest. They had uncovered nothing and were close to starvation and collapse.

As they sailed for home, Knight took the valiant view, and grew ever prouder of his men, like Long John Silver in Treasure Island. Their real treasure lay in human experience; they had followed a map and a dream, and they had returned poorer but wiser. ‘We seemed happy enough as we were,’ he concluded. ‘If possessed of this hoard our lives would of a certainty have become a burden to us. We should be too precious to be comfortable, We should degenerate into miserable, fearsome hypochondriacs, careful of our means of transit, dreadfully anxious about what we ate or drank, miserably cautious about everything.’ It is possible he may actually have believed this.

A few years after his voyage, Knight became a war correspondent for The Times and lost an arm in the Second Boer War. An account of his death published in the New York Times in 1904 turned out to be greatly exaggerated; he lived until 1925. To the end he believed that the treasure of Trinidad was real, and there was only perhaps ‘one link in the directions’ that had led him astray.