‘Make me an offer!’ W. Graham Arader III tells me after I had asked him about buying some of his most treasured possessions. ‘Everything’s for sale!’

This came as little surprise. W. Graham Arader III is the biggest map dealer in the world (the wealthiest, the most famous, the most combative and bombastic, the most feared, the most loathed) and I am in his bedroom, looking at the maps on his walls and getting the impression that in Arader III’s world everything has really been for sale for ever, with the possible exception of his wife and seven children (one of whom is called W. Graham Arader IV). Every inch of Arader III’s six-storey townhouse on the edge of Central Park is covered in maps – above his bed, above the fireplace, over and across his desk and over the doors. I think the walls are papered rather than painted, but it is not always possible to tell. The only places that haven’t got maps on them are those covered with his other passion, rare natural history prints.

What sort of maps does he have? Every type of map! Or at least every type of map that has value, beauty and rarity, which means a concentration on nineteenth-century America and sixteenth-century Europe, all the great names. This is his Madison Avenue home and his showcase, but he also has four other galleries around the country. Between them they display a classic, framed history of cartography – Ortelius, Mercator, Blaeu, Visscher, Speed, Hondius, Ogilby, Cassini, John Senex, Carlton Osgood, Herman Moll and Lewis Evans – and the stories they portray serve as a neat summation of five centuries of trade and power. Here, etched large, is the Venetian silk route, the growth of the Dutch empire, the reigns of Suleiman the Magnificent and Philip II of Spain, the birth of America, the naval highpoint and subsequent decline of Great Britain.

Listening to Arader talk, you would soon believe that he has handled every map of significance in the history of the United States. ‘Yes, I did own the map that Lewis and Clark used to plot their trip,’ he says. ‘I did own the Louisiana Purchase Proclamation signed by Jefferson and Madison … Yeah, I’m number one. We’ve got a stock that is better than the next fifty dealers combined. It might be a billion dollars’ worth of stuff, or five hundred million. It’s really embarrassing that I have as much stuff as I do.’

It is mid-morning. Arader, who is a tall man with a considerable girth, has just been playing squash and is still wearing shorts. As he goes to shower I talk to Alex Kam, one of his strategic planners. He says that he is working hard on building up a new base of collectors, not least online, ‘because if you only focus on the folks who have been spending a lot of money over the years, they get a bit older.’ Kam finds that a lot of new US buyers are specifically interested in buying maps of their home states, ‘those who want to look back at who they were.’ One notable and obsessive exception was Steve Jobs, who used to pay Arader huge prices for botanical prints by the Belgian watercolourist Pierre-Joseph Redouté. ‘He really loved Redouté roses,’ Kam blogged after Jobs died in 2011, in the same month as one of these small nineteenth-century roses on vellum was on sale at Arader Galleries for $350,000. According to Kam, Jobs ‘loved them so much he wanted us to gather up and buy every original Redouté rose in the known universe.’

When Arader returns he says he doesn’t have much time, because he has a ‘five million dollar sale’ he needs to attend. He says he will be both buying and selling, but mostly selling. ‘I have no choice really. The minute I lose sight of being a merchant it’s over. I have overheads of $450,000 a month.’

The W in Arader’s name stands for Walter, he tells me, which was also the name of his father and grandfather. His father was a navigator in the navy and studied maps professionally. When he became Secretary of Commerce of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in the 1960s, map collecting became a hobby, but he was interested, his son says, more in their beauty than in their purpose.

The young Arader began buying maps for him when he was eighteen and spent a year in England before starting at Yale. He bought from all the big names, including R.V. Tooley and Maggs Bros (one of the oldest London antiquarian dealers, achieving particular notoriety a century ago when they bought and displayed Napoleon Bonaparte’s penis). Arader snapped up many pages from the big Dutch and Flemish atlases; in the 1970s these cost perhaps £80, compared with the £8,000 for a fine example today. At Yale he fell under the spell of Alexander Vietor, the head of the map department, and he began selling maps from his dorm room, predominantly, he says, to Jewish doctors at the Yale medical faculty. Then he started selling at antique fairs, where he was astonished to find himself the only map dealer present.

Arader discovered two things: that he had a talent for buying cheap and, after enough schmoozing and vamping with impressionable clients, selling dear; and that the map world was a sleepy place ripe for an alarm call. Thus he began fulfilling what can only be called his eponymous calling: he became a raider. He bought what he claimed were ‘criminally undervalued’ maps and increased their price by ten.

‘Make me an offer!’: W. Graham Arader III at home in his Atlas Room.

s

It is unclear precisely how much the boom in the prices (one hesitates to say value) of rare maps in the 1970s and 1980s can be credited to Arader, and how much he was surfing a wave; the two probably fired each other. His tactics were to buy the very best and rarest, which meant few could compete with the quality of his stock (he has a habit of dismissing lesser items as ‘common as dirt!’). He bought vast amounts, sometimes sweeping up entire auctions and estates, and he dreamed up a plan in which he and a few other leading dealers engineered a mass purchase of all the great maps in the world that weren’t already in institutions.

This didn’t happen in the coordinated way he planned, so he tried to do something similar on his own – and in so doing he became unpopular, very unpopular. ‘Graham’s pretty much at war with all of his colleagues,’ another leading American dealer told me. ‘He doesn’t see much place in the world for anyone but himself, I guess. He adopts a very scorched-earth attitude towards everybody, and he’s called me various names, including “a nest of vipers”. Exactly how I personally manage to be a nest of vipers I’m not sure.’

It is easy to see how people might be offended by Arader’s style. When I emailed him to request an interview he immediately put my letter on his blog. In his reply he said that he found almost all other map dealers ‘dishonest, sacrilegious and wicked … I have been only able to find TWO honest map dealers other them myself in forty years.’

As one might expect from the map world’s P.T. Barnum, Arader is not shy of publicity, and is a favourite of Forbes and Fortune magazine. He is a master of the soundbite: ‘The Sun King Louis XIV – yes he built Versailles, but he was a jerk!’ In 1987, a profile in the New Yorker characterised him as ‘unscholarly yet imposingly knowledgeable,’ which is spot-on. He tells me he reads a book a day. He picks one up from his coffee table, a book about Mount Desert Island off the coast of Maine (he’s just bought the original manuscript map of it). He tells me he has more than 50,000 map reference books in his house, which he claims makes it the finest library of the history of cartography in the world, outgunning the British Library and Library of Congress (debatable, but he often makes the grand, sweeping statement that is difficult to check). ‘When I buy something really important I will buy between a hundred and three hundred books on the subject, I will hire a professor from Columbia University to come and teach me.’

He looks around his bedroom. ‘Very few people can tell you who the King of England was during the French and Indian wars, the American Revolution, the Treaty of Paris, the Louisiana Purchase and the War of 1812,’ he says. ‘That was George III. To have that as part of your core gives one a tremendous thrill for map collecting. You understand why Philip was able to subjugate Europe to the counter-reformation. The counter-revolution occurred because of his cash, his specie, this unbelievable bounty of gold from Mexico City. And these wars of religion, this festering fury, pretty much screwed up Europe for two hundred years … This whole room is the story of what Philip’s barrel of gold does.’

Arader parades his glossy knowledge frequently, but it only goes to reinforce what map lovers have always known: that to know about maps is to know about one’s place in the world. ‘I used to just see pretty maps, but now I see this whole cauldron of history,’ he says. ‘And I really know this history cold – I mean, you have to be a full professor somewhere to really keep toe-to-toe with me on this.’

Arader has a thing about professors, and, like so many successful and wealthy businessmen, he yearns to be respected not for his trading acumen but his scholarship. Accordingly, his ambitions are changing. ‘Having all this is nice, but I hope to give it all away and die penniless,’ he says. ‘I’m sixty. By the time somebody’s sixty, it’s silly to be a person who focuses just on making money.’ He shows me appreciative letters from the Dean of Northeastern University in Boston, thanking him for his generous donations of maps.

He then goes to his computer and searches the file titled ‘Arader: My Dream’. ‘Here it is. This is the course they’re teaching – a different group of maps every day. My idea now is to take these maps and prints out of the museums and out of the libraries and out of the drawers, and use my influence and my wealth to teach the young.’ He says he’s giving them ‘great big slugs of great material,’ because he wants ‘sixty bright-eyed kids every day to look at these maps and embrace history and geography and design and research.’

‘Maps for education,’ Alex Kam adds. ‘That’s where the sizzle is!’

s

The map world is not generally abrasive. I visited several map dealers and collectors, and found most of them civil, learned and passionate. But one thing they tended to have in common was a dislike of W. Graham Arader III.

Jonathan Potter, a mild-mannered London dealer who has known Arader for forty years, was among the most generous when he concluded, ‘He’s done a huge amount for the map business. He’s brought a lot of collectors into the field. But I can’t think of many people who haven’t been bad-mouthed by him.’

Indeed. Most people with whom Arader was once friendly talk about him mainly in respect of their falling out. One such is William Reese, one of the world’s leading experts on maps of the United States, whom we last met in connection with the Vinland map. Reese is a few years younger than Arader, and their paths crossed briefly at Yale (he was the man Arader called ‘a nest of vipers’). When I visit him in his office in New Haven, Connecticut, in September 2011, he is cynical about Arader’s new-found philanthropic urges. He tells me that when he had asked Arader to match a $100,000 donation he had given to Yale to help create a digital catalogue of its map collection, Arader had ridiculed his letter and posted it on his blog.

Reese is from Maryland, but a lot of his family grew up within walking distance of Yale. His professional interest in maps began as an adjunct to his interest in antiquarian books, but he says he has loved maps since he was young. ‘I’m the sort of person who will take a coast-to-coast plane ride and follow our progress with a nationwide road map, as if we were doing it on the ground.’

His lucky break in the map world sounds like one of those mythical stories of finding a Rembrandt in the attic. In 1975 he was browsing through a big sale of a recently deceased book collector called Otto Fisher. Reese had originally gone to look at the picture frames, but then found something interesting in the rug sale. It was a map rolled up in brown butcher’s paper. ‘I felt very excited,’ he remembers. ‘I was pretty sure I knew what it was.’ He had taken a course in Mesoamerican archaeology, and he thought that the map, which showed a Mexican valley from the sixteenth century, was on paper made from fig-bark. He paid $800 for it. When he got it home he narrowed it down to about 1540. He discovered that there was also another map on the other side. He decided to offer it to Yale, where he was in his second year studying American History. ‘I showed it to them and we all sat there poker-faced. They asked, “Well what do you want for it?” It then cost $5,000 a year to go to Yale, so I said, “I’d like $15,000!”’

The college agreed. Reese instantly thought ‘Damn!’ It’s now hanging in Yale’s Beinecke Library, not far from the Gutenberg Bible. ‘At the time it was probably worth about $25,000,’ Reese thinks. ‘Now it’s probably worth two or three hundred thousand. But I don’t care because it completely set the course of my life, and I walked out of there walking on air. I thought, “I can make a living out of this”.’

I ask Reese how many serious (scholarly and moneyed) map collectors there are in the United States, and the answer surprised me: ‘very few’. It was the ‘You Are Here’ factor again – most collectors collect only for a few years, predominantly interested in the area they were born or live in. Others only collect maps of the world. ‘They start with the Mappa Mundi as their first interest,’ Reese says, ‘and then go on from there. Most of the people who collect like that I would define as real amateurs, enthusiasts. Often their collecting is defined by their wall space – once they fill their walls, they’re done.’

There are far fewer people who take it to the next level, where they store maps in drawers. Reese believes there are only ‘a couple of dozen’ very serious map collectors in the US, perhaps a couple of hundred worldwide, not including the institutions. There is one simple reason there aren’t more: the scarcity of the really great items. ‘With maps there’s a risk that at the very, very top end there may soon cease to be a market,’ Reese says. ‘They’ve all been snapped up.’

But something strange happened to the supply of very fine maps in the first years of this century: items that were highly desirable but previously not around, began to appear. Bill Reese noticed it with rare American maps of the seventeenth century, particularly those drawn by the French explorer Samuel de Champlain, the first man to properly map the Great Lakes. Dealers suddenly had maps for sale that hadn’t been seen for decades, and although they swiftly disappeared into private collections, they created a rare liquidity in the marketplace.

There was, of course, a reason for this: these maps had been stolen.

s

In September 2006 a fifty-year-old man called Edward Forbes Smiley III was sentenced to 42 months in jail and fined almost $2m after he admitted stealing 97 maps from Harvard, Yale, the British Library and other institutions. It was the biggest map theft anyone could remember, and it shocked libraries not only because of their losses (many of which they were unaware of until Smiley’s arrest), but also because they had trusted him and enjoyed his company. Or at least they enjoyed his connoisseurship: Smiley had been a dealer since the late-1970s and in the trade was considered ‘one of us’.

The unacceptable face of map-dealing: Edward Forbes Smiley III.

But in fact he was really a common criminal. He used a blade from a craft knife to slice pages from books and atlases, which he would then disguise by trimming again. He favoured this method over another classic map thief’s trick: after rolling a ball of cotton thread in your mouth, you unravel it against the bound edge of a map you wish to steal and close the volume; in a short while the enzymes in your saliva will thin the binding until it is weak enough to remove.

Bill Reese remembers dealing with Smiley in 1983 – the first and only time he trusted him. He sold him an American coastal atlas for $50,000, but his cheque bounced (he says he got the money eventually). Their paths crossed subsequently at auctions and map fairs, but their next proper encounter was in 2005, when Reese was brought in by Yale to assess the thefts from their collection. (Smiley had been caught at the university’s Beinecke Library when a librarian spotted an X-acto blade on the floor; he was found with several rare maps in his briefcase and blazer pocket when he fled the building, including a map by Captain John Smith from 1631 – the first to mention New England.)

To enable Reese’s audit, the library’s map department was closed for an entire term. One of the problems he encountered was that the maps had not been fully catalogued electronically, something Forbes may have counted on when planning his targets. ‘Smiley stole cards out of the card catalogue to cover his tracks,’ Reese says, ‘but it didn’t work because they had a microfilm that had been made of the card catalogue in 1978, which he didn’t know about.’

s

The Forbes Smiley case has had a modest impact on how leading research institutions protect their treasures. They tightened their security as best they could, and often added CCTV coverage. But many librarians felt uneasy at having to screen readers they had trusted for decades, and new security measures ran counter to the perspective of a library as a civil place designed for the free dissemination of knowledge. As one curator said at the time of the Smiley saga, ‘we’re in the business of being vulnerable.’

Small-scale map theft began at the same time as maps began; before they were valuable and decorative, they were just useful. But the significant heist stories in the last half of the twentieth century are compelling not only for their audacity and Cold War techniques, but also for the grand scale and serial nature of their crimes. Thieves kept on going back and back to the same rich well, as if a bank had left its vault open and the keys to the safe on the table.

In March 1963, for example, several colleges at Oxford and Cambridge found that for the previous ten months a man named Anthony John Scull had been razoring through their atlases with unfettered glee. He stole more than five hundred maps and prints, the majority from King’s College, Cambridge. They included all the greats, at a time when all the greats were not under white-gloved supervision: Scull got away with Ptolemy, Mercator and Ortelius. In those days even rare maps didn’t achieve great prices, but there is no doubt that dealers and even a couple of auction houses were grateful for Scull’s supply. The total value of the stolen maps was estimated at £3,000 (perhaps £3m today) but the greater damage was to the broken atlases and books left behind.

In the United States, the most bizarre and cinematically heroic story may be the ‘cassock crimes’ of 1973, in which two American Benedictine priests stole atlases from leading college libraries and stored them in their monastery in Queens. Then there was the story of the Scandinavian thefts orchestrated by a British pair, Melvin Perry and Peter Bellwood, who thought – rightly as it turned out – that the best place to steal maps at the end of the 1990s would be the Royal Library in Copenhagen. Both Bellwood and Perry had previous convictions for thefts from the British Library and elsewhere when they started flying to Denmark. (Bellwood had a nice touch: on one visit he gained the librarians’ trust by handing in a 500 Kroner note he had ‘found on the floor’. He got away with Ortelius and Speed.)

Another famous case, again in the 1990s, was that of Gilbert Bland, who had stolen around two hundred and fifty maps before he was spotted by a reader ripping a page from an atlas at the Peabody Library at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Bland sold his maps from a shop he ran with his wife in Florida, a stock he had purloined from nineteen libraries, from Delaware to British Columbia. His defence? ‘I just wanted them.’ Bland became the subject of an entertaining book, The Island of Lost Maps, by Miles Harvey, which also features a star turn from Graham Arader. Harvey called Bland the ‘Al Capone of cartography, the greatest map thief in American history,’ though that was before Forbes Smiley and his blade had appeared on the scene.

s

Where else would an eager person go for their cartographic education if not an increasingly fortified library? How about a series of tutorials run by W. Graham Arader III and his colleagues? Shortly before I visited him, Arader had begun placing advertisements for a summer course for high school and college students on which they could learn aspects of dealing. The course cost $1,200 a week and included what Arader had classified as the four key steps to making a sale: ‘A: Introduction. B: The Artwork exists. C: The Artwork can be owned. D: The Sale of the Artwork.’ Successful applicants would also receive lessons on maintaining relationships with clients and how to best use the Internet for trade. ‘Lots of my clients pressure me into hiring their entitled children,’ Arader told me. ‘So now they’ll have to pay for it. A kid comes in [to work with me], doesn’t do anything the entire summer, gets about $5,000-worth of education – that’s over!’

When I asked Arader for some of the key nuggets that he’d be offering his students, he directed me to his blog. Here he spoke of simple advice: compose handwritten thank-you letters; don’t bombard your clients with emails but offer wise, measured and timely advice about items they might be particularly interested in.

There was also advice about spotting fraudulent maps that were masquerading with ‘original colour’. In June 2011 Arader had taken a group of four interns (the last of the unpaying lot) up the road from his house to a viewing of an upcoming auction at Sotheby’s. They settled on Lot 88, a classic seventeenth-century study of Africa with many maps by the Dutch geographer Olfert Dapper.

‘It had the most amazing example of fake original colour imaginable,’ Arader noted. ‘We were all completely fooled – the greens oxidized through the paper almost perfectly. My first reaction was great excitement and lust for what looked like a magnificent book. But it was not.’

Arader’s excitement soon turned to fury. He saw how cleverly the forger had tried to replicate the oxidisation of green that was usually the key indication of genuine contemporary colour. ‘The only way to protect yourself is to look at atlases with original colour in the great libraries of the world,’ he advised his interns, and vowed to expose the worst culprits. ‘Hopefully one of these creeps will be lured into suing me so that we can use the courts to finally come to an answer. I am on the warpath! Be warned.’

In 1998, the Australian couple Barbara and Allan Pease self-published a funny and gentle book called Why Men Don’t Listen & Women Can’t Read Maps: Beyond The Toilet Seat Being Up. Within a year, the book had lost the bit about the toilet seat but had become a global hit (12 million copies), and not long after that it had become one of those books that people talked about at bus stops and at work. It was a war-of-the-sexes study a bit like John Gray’s Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus, except this one took things further, veering into bonkers-land. It explained why men can’t do more than one thing at a time, why women can’t parallel park, and ‘why men love erotic images and women aren’t impressed.’

With reference to maps, their findings are unequivocal. ‘Women don’t have good spatial skills because they evolved chasing little else besides men,’ they assert. ‘Visit a multi-storey car park at any shopping mall and watch female shoppers wandering gloomily around trying to find their cars.’ The Peases were really confirming a stereotype that had existed since Columbus laid out his sailing gear: men, nervous of asking a stranger the way, just get on better with directions that fold.

But is any of it true?

Several years before the Peases turned their success into a cottage industry, academics had begun publishing gender-related map studies of their own. Actually they’d been doing this for a century, but from the late-1970s they began appearing with an unusual urgency. In 1978 we had Sex Differences In Spatial Abilities: Possible Environmental, Genetic and Neurological Factors by J.L. Harris from the University of Kansas; in 1982 J. Maddux presented a paper at the Association of American Geographers entitled Geography: The Science Most Affected by Existing Sex-Dimorphic Cognitive Abilities.

Their approaches and findings varied, but yes, most psychological studies seemed to feel that when it came to such things as spatial skills, navigation and maps, men did seem to have the upper hand. It was thought likely that this would explain why the number of men doing PhDs in geography in the 1990s outnumbered women 4 to 1. It may also explain why, in 1973, the Cartographic Journal published a report by a man called Peter Stringer that stated he had recruited only women in his research into different background colours on maps because he ‘expected that women would have greater difficulty than men’ in reading them.

But what if there was a very simple explanation to all of this, beyond unfettered prejudice? What if men and women could each read maps perfectly well, but in different ways? What if the only reason women had trouble reading maps is because they were designed by men with men in mind? Could maps be designed differently to appeal to women’s strengths?

In 1999, a project was carried out at University of California by academics in geography, psychology and anthropology. This involved an extensive review of the existing literature on spatial abilities and map-reading, well over a hundred papers by now, and also a new series of experiments involving 79 residents of Santa Barbara (43 women and 36 men, aged between 19 and 76).

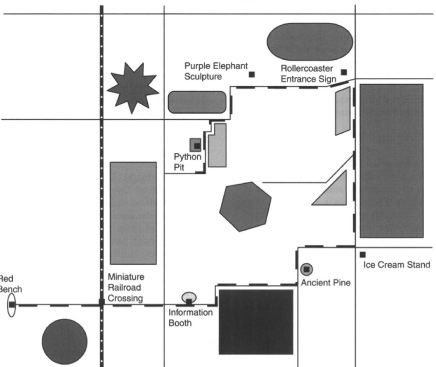

The strongest conclusions in the literature – that men were better than women at judging the relative speeds of two moving images on a computer screen, and also at successfully judging the mental rotation of 2-D and 3-D figures – were thought to be not overly practical in real world situations. So the new experiments involved a bit of walking about and map sketching, as well as responding to verbal directions and learning to read fantasy maps. One of these showed an imaginary theme park named Amusement Land. It measured 8.5” × 11” and featured such landmarks as Python Pit, Purple Elephant Sculpture and Ice Cream Stand; having been given some moments to study it before it was taken away, participants then had to sketch the map for themselves with as many landmarks as possible. They were asked to perform a similar task with another fictional map entitled Grand Forks, North Dakota, which was actually a rotated map of the city of Santa Barbara. They were also led on a walking tour around a part of the university campus, before being given a map of the area and asked to write in the route they had taken.

Amusement Land, where cartography, sex-differences and ice cream meet, at last.

The authors concluded that although men were better at some tasks (estimating distances and defining traditional directional compass points), women were better at others (noting landmarks, some verbal description tests). When it came to map-use, both imaginary and real, women ruined the Peases’ book title; they could read maps as well as men, only they read them slightly differently.

And there was growing evidence that they knew it. In 1977, the Journal of Experimental Psychology published an experiment that found that 20 of 28 male participants but only 8 of 17 females regarded themselves as having a ‘good sense of direction’. But by 1999 this had shifted, at least in Santa Barbara, as residents of both sexes reported feelings of growing ability. Out of ten categories (including ‘It’s not important to me to know where I am’, ‘I don’t confuse right and left much’ and ‘I am very good at giving directions’) there was no statistically significant difference and high self-belief among both sexes. Men did appear to be more confident when in the category of ‘I am very good at judging distances’, but on the big issue of ‘I am very good at reading maps’ there was again no discernible difference.

What, then, is the perceived problem? The problem is, although women have no difficulties with navigation, the way they are told to navigate may be at fault. In December 1997, in an early British edition of Condé Nast Traveller, a writer called Timothy Nation wrote a brief essay wondering why, when we wander the streets of London it is far easier to get around by looking out for well-known landmarks than it is to rigidly follow a map or compass. This was because maps only follow the line of a street – they look down. But when we walk we tend to look up and around. The flat, two-dimensional, look-down approach is suited to cognitive strategies used by men, but it is one that generally puts women at a disadvantage.

Timothy Nation, whose real name was Malcolm Gladwell, the writer not yet known for his books The Tipping Point and Blink, then examined a famous experiment conducted at Columbia University in New York City in 1990 involving mazes and rats. This found that, when searching for food, male rats navigated differently to their female counterparts. When the geometry of their testing area was altered – dividers were introduced to create extra walls – the performance of male rats slowed down, while there was little effect on females. But the opposite was observed when the landmarks in the testing room – a table or a chair – were moved. Now the females became confused. This was the big news: males responded best to broad spatial cues (large areas and flat lines), whereas females relied on landmarks and fixtures.

Could this have been a freaky result? Possibly, but several other experiments in the last twenty years have produced similar findings. The most recent was in 2010, when the American Psychological Association reported an Anglo-Spanish experiment in which even more rats were placed in a triangular-shaped pool to find a hidden platform. Again a comparable result – female rats benefit from locational cues, whereas the males race by them.

Similar experiments have continued with men and women, again with comparable results. Few psychologists would now argue against these navigational differences. What is less certain is how these changes have come about. But we may well be back on the African plains with the hunter-gatherers. In this theory – and it’s a plausible one – men and women’s brains both developed through their navigational skills, but in different ways. Men sought the broad sweep of tracking and pursuit over large areas, while women tended to be down with the roots and berries, foraging skills aided by memory, and memory aided by landmarks.

The traditional map, however, a 2-D flat plane, is designed by hunters for hunters. Female gatherers don’t get much of a look in. But with 3-D maps – either panoramic views with highlighted landmarks on paper, or digital renderings on screen – the road ahead becomes instantly more readable.

One further experiment, conducted in 1998 by social psychologist James Dabbs and colleagues at Georgia State University, found that the strategy differences of the sexes extend to verbal communication. Dabbs found that when men give directions they tend to use compass points such as north or south, whereas women focus on buildings and lists of other landmarks en route.

So perhaps Barbara and Allan Pease were right after all, or at least half-right. Men don’t listen because they don’t need to listen so much. And women can’t read maps because they’re the wrong sort of maps. What can possibly save this troublesome marriage? A plastic dashboard-mounted box perhaps?

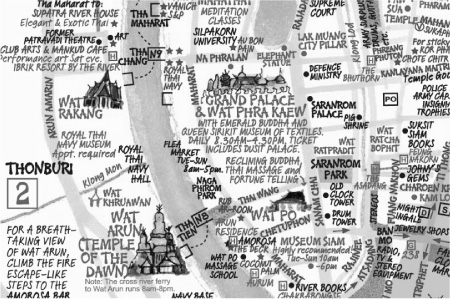

Maps for Women? Nancy Chandler, based in Bangkok, has been producing highly successful ‘3-D’ maps of Thailand for the past two decades. They look crowded and a little chaotic but feature hand-drawn landmarks and useful text, as well as colour-coding for different attractions. And, yes, she notes that her maps are bought and used predominantly by women.