The headquarters of Google Maps in Mountain View, California, contains the sort of diversions you’d expect in any standard office at the forefront of world domination – table football, table tennis, air hockey, a copious range of free quality snacks. The campus on which it stands, the Googleplex, also has a picnic area, a vegetable garden, cycle paths, massage rooms, a car wash, a dry cleaner, a crèche, a beach volleyball court, a dog parlour, a medical area with a dentist, a hairdresser and a carbon-free bus service to take you anywhere you’d like to go, personal security access permitting. There is visual humour too, such as the giant doughnut in an outdoor eating area, and the enormous red map pin outside the Google Maps building.

Inside the Google Maps building there are other jokes, including a green road sign that hangs above a cubicle. ‘Welcome to Earth,’ it reads in a Douglas Adams way. ‘Mostly harmless!’ On the reverse: ‘Now Leaving Earth. Please check oxygen supply and radiation shielding before departing. Y’all Come Back Now!’ And then there are the wooden signposts. There are two of them, each about five-feet tall, deliberately chipped and distressed to resemble something from a hundred years ago, something from a mid-west hiking trail perhaps, or a post you’d hitch your horse to. But they were made in the first years of the twenty-first century, the period in which Google Maps did away with the need for signposts altogether, and established itself as the newest revolution in cartography since – in fact, it is hard to think of a similar event since the Great Library of Alexandria opened for business around 330 BC.

The directions on the signpost point to the names of Googleplex meeting rooms, and read like the dead wood that they necessarily are: Eratosthenes, Marco Polo, Leif Ericsson, Sir Francis Drake, Ortelius, Vasco da Gama, Vespucci, Magellan, Livingstone, Stanley, Lewis and Clark, Shackleton, Amundsen and Buzz Aldrin. One day, perhaps, they will name a small plank on the signpost after Jens and Lars Rasmussen, the brothers who brought Google Maps to the world; or after Brian McClendon, the man chiefly responsible for inventing Google Earth.

y y y

I am standing with McClendon at Google’s eight-screen map-wall, also known as the Liquid Galaxy. He swoops around the world he helped create with the same planet-on-a-string omnipotence that was once enjoyed by Mercator, or maybe God. ‘This is really cool,’ he says as he zooms out to the spinning blue-green earth, before zeroing in on a basketball court in Lawrence, Kansas, his home town.

When I visited in the spring of 2011 this was the big new thing – going inside buildings. It was still early days for internal mapping (McClendon said it would be a real palaver getting permission to take photos inside private homes), but it signified the company’s – and cartography’s – intentions: to map every place on earth in more detail than anyone had ever managed before, and in more detail than most people had previously considered necessary. It brought to mind the absurd vision of Lewis Carroll in his last novel Sylvie and Bruno Concluded, where the ultimate map was on the scale of a mile to a mile, or Jorge Luis Borges’ fantasy conceit On Exactitude in Science, published in 1946 but purportedly written in 1658, recalling a time when ‘the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it’.

The whole wide world at your control: the Liquid Galaxy map wall at the Googleplex.

This time, of course, the entire map of the world, inside and out, wasn’t being drawn to be big, but drawn to fit on a mobile phone. And it wasn’t really being drawn, but photographed and computerised, rendered and pixelated from street level and satellite level. It was the product of applied science, and as such it was impersonal, unemotional, factual and more accurate and current than any map we’ve ever used. And such a thing is useful: according to the research company comScore, about sixty million people per month used Google maps in the first quarter of 2012, and the company was by far the most dominant player, with 71 per cent of the market of online computer maps. On smartphones, Google had a 67 per cent share of the fifty million people who used mobile maps to get around. In the summer of 2012, Google estimated that about 75 per cent of the world’s population had been covered with its high-resolution maps; about five billion people could say they were able to see their house. But there was still a long way to go.

Brian McClendon, a youthful-looking forty-eight in his Google uniform of polo shirt, jeans and trainers (he actually looked a bit like a young Bill Gates), was the first to admit that he was not a cartographer, despite the fact that he was in charge of Google Maps, Google Earth, Google Ocean, Google Sky, Google Moon and Google Mars. The clue was in his job title: Vice President of Engineering. His stated ambition was nothing less than a digital, instantly accessible live atlas of the entire world, something that would show not just the things that old-school atlases showed (major cities, geological facets, coastal contours, comparative data) but every house on every street and every car in every driveway. Then there would be the inside of buildings, enabling, say, a tour of the Louvre, and universal 3-D imaging with which to better judge distance and height, and then all that route-planning and live traffic information we’ve experienced with sat nav. Not forgetting all those apps that use Google to coordinate the other gimmicks on our computers and phones, such as photo location, the precise whereabouts of our friends, or (the ultimate dream of commerce) an app with the foresight to offer us a special deal just a few seconds before we walk past the shop where that special deal awaits. And that’s just on the ground in our cities; the wilderness too will be fully mapped, the poles and the deserts, and names will be apportioned by Google where none existed before, just like cartography of old. And don’t get McClendon started on the mapping of coral on the ocean floor, or the seamless recreation of craters of the Moon.

In such a way Google would not only show the entire world, but also have the power not to show it; it had the power to control information in ways that the most crazed eighteenth-century European despot could only dream about. This ambition, and this power, is less than a decade old, and is already very far removed from Google’s original purpose when it began in 1998, which was to build a search engine which ranked web pages in order of popularity and usefulness (five years before there had been no need for such a company, for in 1993 there were only 100 websites in the world). But now ‘search’ wasn’t the dominant thing any more; it was allying the results of search to maps.

y y y

In the spring of 2005, Sergey Brin, Google’s co-founder, wrote a letter to his shareholders in which he made clear that the company was keen on new directions. Accordingly there were several new products that had been (or were just about to be) launched, including Gmail, Google Video and Google Scholar. There was also Google Maps, which would provide planning and driving directions from the web, and Google Earth, a downloadable program providing almost sixty million square miles of stitched satellite images. The first of these developments was nothing exceptional to those familiar with the services of AOL’s MapQuest and MultiMap, although the increased speed at which the pre-rendered map tiles appeared on a screen and the integration of maps into Google search results was rather handy. But the introduction of Google Earth offered one of the Internet’s ‘hey wow’ moments. No one, with the possible exception of Neil Armstrong and friends, had been able to see the earth in this way before, swooping and zooming from zero gravity, breathlessly zoning in on places we had visited on our holidays and places we would never visit if we lived for ever.

And where did people search first? The very same place they had looked for when they viewed the Mappa Mundi at the end of the thirteenth century, the place where they lived. ‘Always,’ Brian McClendon told me. ‘And every new version, people go and say how does my town or my house look.’ This is a part of human nature – the desire to know where we fit within the grander scheme of things. But it is also emblematic of the new form of cartography that Google and its digital counterparts represent: Me-Mapping, the placing of the user at the instant centre of everything.

Before it was bought by Google in 2004, the software that became Google Earth was previously known as Keyhole, which was co-founded by Brian McClendon. He says he knew he was onto something in the late-1990s, when he and colleagues at his previous company, Silicon Graphics, began combining images of the globe with images of the Matterhorn and nearby terrain, zooming in and out on a piece of hardware that cost $250,000. From the Matterhorn, Keyhole advanced to the Bay Area of San Francisco and zoomed into aerial images of a shopping centre. The commercial breakthrough occurred in 2003, when CNN began using the software in its coverage of the Iraq war. McClendon and his colleagues presented Keyhole to Google founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page in April 2004, and had an offer for the company within twenty-four hours.

Google’s instincts were spot-on. There was so much public interest that when Google Earth launched its free service on 28 June 2005 the entire Google computer system almost melted (and new downloads were severely restricted in the first few days as new servers were deployed to meet demand). By the end of the year, Google Earth had become the key geographical tool on tens of millions of personal computers, and its early adopters would call their friends round so that they could feel slightly queasy together. An atlas had never been so much fun.

I asked McClendon what he thought the great explorers of the sixteenth century would have made of the world in zoomable form. ‘Oh, they would have completely understood it.’ In fact, they would have known slightly more about the world than early users of Google Maps did. In 2005, Google could only render maps of the United States and the UK, and there was no mainland Europe or Central or South America. The maps it did show were licensed from already well-established companies such as Tele Atlas and Navteq, and a few government agencies, but it had none of its own. The Google world only filled out slowly: in 2007 there was still no Pakistan or Argentina, and there were none of the places first touched by Amerigo Vespucci more than 500 years before. But by 2009 this had been rectified, and Google had captured almost the entire world, enhanced by the purchase of a vast cache of satellite imagery.

McClendon says there is an assumption that satellites have rendered human mapping obsolete, but they have strict limits: they can’t track local details, they can’t name things, they can’t relate spatial awareness to real-world issues. Satellites may have seen the Antarctic, but they could never define its boundaries or obscurities. In the true wildernesses – the poles, the deserts, the jungles, even the unpopulated regions of fully developed countries – Google employees are increasingly setting off not in cars with cameras on the roof, but with cameras on backpacks and on the wings of planes, and they do well to arm themselves with the knowledge of border conflicts and the heated disputes over nomenclature.

As it becomes increasingly powerful, Google finds that it encounters obstacles it never anticipated, often geopolitical and social ones that seldom detained mappers with empire-building intent in centuries past. ‘We have places that are named that are claimed to be owned by three different countries,’ McClendon says. ‘And they have two or three names associated with them. We regularly get yelled at by countries. I didn’t think we’d be that important. As it turns out we are more important to argue about than anything else. When the Nicaraguans invaded Costa Rica, they blamed Google Maps for doing it because our borders weren’t right. They said that we just went to the land that Google had given us.’

On the day we met, McClendon said he had a new and seemingly less controversial passion: mapping the world’s trees. It was a maniacal goal. By some estimates there are 400 billion trees in the world, and Google believes it has catalogued about one billion of them. ‘So we have a long way to go – figuring out how to detect them, locate them, know their species.’

At the end of June 2012, McClendon gave a talk at the annual convention for Google developers and media in San Francisco. He began with a classic misconception: ‘Hic sunt dracones,’ he said. ‘This is what they wrote on old maps when they were drawing them and they didn’t know where the borders were, to tell the people looking at the maps “don’t go there, you might fall over the cliff”. But our goal at Google has been to remove as many dragons from your maps as possible.’

y y y

I had been driven to Google by a colleague of McClendon’s named Thor Mitchell. Mitchell began working for Google in 2006 after a long spell at Sun Microsystems, and he now managed a department called Google Maps API, which provided a set of tools to enable people outside the company to make software applications involving Google Maps. These could take the form of constructing location devices on your phone, or using maps on your website to show your restaurant or shoe store and boost commerce.

We had met at Where 2.0, a three-day conference in Santa Clara, near San Jose in California (certainly near enough to enable people at the conference to joke that they had known their way to San Jose). The conference attendees, who came from eighty countries, were all engaged in the business of maps and location, and the presentations they gave buzzed with phrases like ‘proximity awareness’, ‘cross-platform realities’ ‘dataset layering’ and ‘rich context beyond the check-in’. There were contributions from many of the old big players, including Nokia, Facebook and IBM, and some of the relative newbies too, including Groupon and Foursquare (the concept of ‘old’ in the digital mapping world meant three years or more).

But the big news that week came not from the scheduled speakers, but from a surprise presentation from two attendees called Alasdair Allan and Pete Warden. Allan, a senior research fellow at the University of Exeter, had just finished some analytical work on the Fukushima nuclear disaster when he was ‘looking for some cool stuff to do’. What he found, after some digging in the recesses of his MacBook Pro, was that every call he had made on his iPhone had been logged on his computer with coordinates for latitude and longitude. The information was not encrypted, and was available for everyone to see. He didn’t suspect anything sinister on the part of Apple, but he was disturbed by the potential invasion of privacy. Phone carriers had by necessity logged customer calls to monitor usage and issue bills, but this was something else – the open tracking, for a period of almost a year, of an individual’s whereabouts. Allan and Warden had no problem translating the recorded coordinates into maps, and one particularly striking screengrab from their presentation showed a train trip from Washington DC to New York City, with Allan’s whereabouts being registered every few seconds. And of course Allan and Warden weren’t alone: we were all being tracked, and all – potentially at least – being mapped.

The glowing promise of digital mapping has other downsides. Because the new digital cartography is really just an amalgamation of bits, atoms and algorithms, it should perhaps come as no surprise that all our WiFi and GPS devices send as well as receive. Some of this information we provide voluntarily when we enable the location option on our photo-sharing programs or apps, or when we let our sat nav feed back traffic information while on the road, but some of it is just sucked from us without our knowledge.

As we drove to the Googleplex, Thor Mitchell and I talked about the 3-D wonders of Google Street View, the hugely popular web application providing panoramic urban maps of the world. When it launched in 2007 it covered just five US cities, but by 2012 this had expanded to more than 3,000 cities in thirty-nine countries. Billions of drive-by photos had been stitched together to form a seamless cursor-led stroll or drive for its users, and Google cars had driven some five million unique miles to enhance the maps that it had licensed from other companies. But this too was now coming under scrutiny concerning privacy issues.

Between the beginning of 2008 and April 2010, the cars that had been gathering information for Google’s maps had also been sweeping up personal information from the houses they passed. If you were on the Internet as one of Google’s Subarus rolled by, Google logged the precise nature of your communications, be it emails, search activity or banking transactions. As well as taking photographs, the cars had been consciously equipped with a piece of code designed to reap information about local wireless services, purportedly to improve its local search provisions. But it went beyond this, as another program swept up what it called personal ‘payload data’ and led the Federal Communications Commission in the US and other bodies in Europe to investigate allegations of wiretapping. While there is no evidence that Google has made use of the personal information, a spokeswoman for the company did admit that ‘it was a mistake for us to include code in our software that collected payload data’. At the beginning of its life, Google had one publicly stated mission: ‘Don’t be evil.’

y y y

But then there was another problem for Google Maps: something called Apple Maps. In June 2012, Apple announced that its forthcoming new mobile operating system would appear without Google Maps, which would be replaced with a service of its own. This would not actually consist predominantly of maps of its own making, for the company had already licensed Tele Atlas maps from TomTom. But its intent was clear: maps were the new battleground, and Apple no longer wanted to rely on or promote those of a rival.

But how would Apple’s maps differ, and how would they hope to compete with such a giant in the field? Its big idea, it claimed, was try to bring new consumer joy to digital cartography, in the way it often did to other services. It promised greater ease of use, smooth integration with both its software and hardware, and an enhancement of such things as 3-D imaging, voice directions and live traffic. It would attempt to add real-time information allied to public transport, commercial buildings and entertainment venues, possibly enabling seat reservations and other purchases through iPhone credit.

Two things were happening at once here – integration and exclusivity. The technological capabilities of maps continued to astonish, and they were increasingly becoming what they had been in the age of the Spanish conquistadors – guarded, proprietary and inestimably valuable as routes to further riches. Google responded to Apple’s withdrawal with a weary shrug that said ‘good luck – it’s a tough world out there’. It told a press conference that it invests hundreds of millions of dollars each year on its mapping services, and that in eight years it had built up an army of snowmobiles, boats and aeroplanes to achieve its aims. It promised a new feature called Tour Guide, enabling users to ‘fly’ over cities in 3-D. It also dramatically cut the prices of using its Google Maps tools on websites with heavy traffic, from $4 per 1,000 map loads to 50 cents per 1,000 map loads.

This wasn’t the first time Google’s mapping had faced serious competition. At the time of Apple’s announcement, the online directory ProgrammableWeb counted 240 companies offering their own map platforms, more than double the amount in 2009. Some are bigger and more comprehensive than others. In 2009 Microsoft launched Bing Maps, an improvement on its earlier Virtual Earth with a refreshed ‘bird’s eye’ view and an expanded global range (its base maps were supplied by Nokia’s American subsidiary Navteq, which also supplied Yahoo Maps).

And a few days after Apple’s announcement there was the prospect of another major player. Amazon’s Kindle devices and an anticipated Amazon smartphone would both benefit from handheld mapping, and the leaked news in June 2012 that the company had recently purchased a 3-D mapping start-up suggested that the journey was well underway.

y y y

At Where 2.0, Blaise Aguera y Arcas, the principal architect of Microsoft’s Bing Maps, promoted his product in a novel way. It was ‘an information ecology’, he claimed, which provided a ‘spatial canvas … a surface to which all sorts of different things can bind’.

In one sense this appeared to be a new artistic vision, but in another it was merely a new grand language to describe something that had been going on elsewhere for a while – the map mash-up. This had been happening in music, especially, the ability to take one bit of a song and crash it into another, an extreme form of sampling. The same was now happening with maps, and it was the hottest cartographical trend of the digital age.

Personalised, crowd-sourced additions may render a map subversive, satirical or simply newly useful. A list of the most popular mash-ups on ProgrammableWeb (in the middle of 2012 there were more than 6,700 to choose from) includes a map of where items on the BBC News are located in the world, the sites of the Top 50 medical schools in the US as tabled by US News (almost four-fifths east of Chicago) and many marine vessel and flight trackers (so you can point your phone at a boat or plane and find out what it is, where it’s come from and where it is going).

And then there are others that are just timesucks: the vague location of the ‘Top 99 Women’ as voted by the drooling staff of Askmen Magazine (the red location markers, which are accompanied by photos and videos, are, predictably, mostly sited in California, but there are also top women in Germany, Brazil and the Czech Republic). Slightly more productive are several rock band road trips, on which you may follow the route of fans as they plot cross-country US drives listening to local artists en route (so pass your cursor over Baltimore, Maryland, and you’ll hear Frank Zappa, Animal Collective, Misery Index and more). Most of these use Google Maps and Bing Maps as their base, and all would have been impossible even five years ago.

One of the most compelling is Twitter Trendsmap (trendsmap.com), a real-time projection of the world on which the most popular tweeting topics are overlayed in strips. Levels of activity vary according to what time of day one calls up the map, but one is usually guaranteed a lot of hashtags involving sport, political outrage and Bieber. To take a European morning in the summer of 2012, arsenal, vanpersie, wimbledon and shard were all trending in the UK, while Spain was covered with black tiles announcing bankia, higgs, el-pais and particula. India, meantime, was busy with secularism, olympics, bose and discovery, while a sleepy Brazil was covered with casillas, buzinando, pacaembu and paulinos.

y y y

The Twitter map is oddly reminiscent of a project from sixty years ago, when visitors to the Festival of Britain encountered a map called ‘What Do They Talk About?’, a regional survey of conversational habits in the British Isles. Elaborately designed by C. W. Bacon for the Geographical Magazine and Esso (lots of swirling banners of text and schoolbook illustrations, not that far from Matthew Paris in 1250), it stated that everyone talks about the weather, but if you travelled to Northern Ireland they also talked about No Surrender, while in Portsmouth it was Pompey’s chances in the football league. If you went up the east coast of Scotland from Edinburgh to Aberdeen you would also be able to engage the locals with The New Pit, Golf, What the Bull Fetched and Philosophy, Divinity, Fish.

Such maps continue to thrive in the analogue world, where they are rightly categorised as art rather than engineering, and they have a rich history. We’ve already encountered some of the zoological classics (the eagles and octopuses, the London tube map’s Great Bear) but there are examples in just about any field you can come up with. There are horticultural maps (Bohemia in the shape of a rose from 1677, by the Bavarian engraver Christoph Vetter, with Prague at the centre and Vienna at the root), and allegorical maps such as the Paths of Life (made by B. Johnson in Philadelphia in 1807, showing ‘Humble District’, ‘Gaming Quicksands’ and ‘Poverty Maze’), and also amorous examples that became popular as Victorian postcards (one shows the course of the Truelove River, flowing through ‘Fancy Free Plateau’, ‘Tenderness Crossing’ and the ‘Mountains of Melancholy’ before settling at ‘Altar Bay’ and the ‘Sea of Matrimony’).*

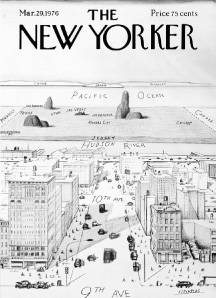

Perhaps the most celebrated of all is Saul Steinberg’s Manhattanite’s view of the world – a map that appeared on the cover of the New Yorker in 1976 and has been the subject of myriad variations on posters and postcards ever since. In some ways it was a precursor to digital 3-D and birds-eye maps, with the viewer flying over the bustle of 9th and 10th Avenues, crossing the Hudson River into Jersey, and then, with an absurdly telescoped perspective, leaping over Kansas City and Nebraska into the Pacific. A few vaguely significant locations dotted in cross-hatched wheat fields hove briefly into view – Las Vegas, Utah, Texas and Los Angeles to the west, Chicago to the east – and then far off in the distance, the small pink-tinged hallucinations of China, Japan and Russia. The message was simple: everything that happens, happens in self-obsessed New York. It was me-mapping before the iPhone made it de rigueur.

Steinberg’s Manhattanite’s view of the world.

The parody has been parodied many times, but the best modern parallel, and certainly the rudest, is to be found in the work of the much travelled Bulgarian graphic designer Yanko Tsvetkov. Tsvetkov, who works under the name Alphadesigner, may well have constructed the most offensive and cynical atlas in the world, all of it stereotypical, some of it funny. His Mercator projection entitled The World According to Americans showed a Russia labelled simply ‘Commies’, and a Canada labelled ‘Vegetarians’. He has also produced the Ultimate Bigot’s Supersize Calendar of the World, which includes Europe According to the Greeks. In this one, the bulk of European citizens live in the ‘Union of Stingy Workaholics’, while the UK is categorised as ‘George Michael’.

Despite the rigours of digital architecture we should be relieved that maps remain funny, inquisitive and poignant, and that it is often the quirky, inspired hand-drawn one-offs that reveal the greatest truths. A glorious map of the Glastonbury Festival created by Word magazine included locations labelled ‘Man Selling Tequila Off a Blanket’, ‘Route of Aimless 4am Trudging (Contraflow)’, Doorway to Narnia’ and ‘People Actually Having Sex’.

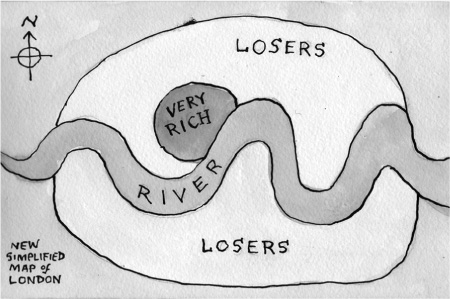

Or how about the New Simplified Map of London by a secretive (but one imagines local) hand going by the name of Nad, on a Flickr site devoted to ‘Maps From Memory’:

And perhaps there is another positive analogue reaction to the neatness and programmed ease of digital mapping. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the modern art world has embraced cartography as never before, a trend heralded by Alighiero Boetti, Jenny Holzer, Jeremy Deller, Stanley Donwood and Paula Scher, and most passionately by the London-based artist and potter, Grayson Perry.

y y y

Grayson Perry’s 2011 show at the British Museum, The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman, contained pots, tapestries and drawings that suggested that we had entered a new golden age of hand-crafted wayfinding, albeit often of a mythical and highly autobiographical nature.

Perry had previously drawn a huge and complex modern-day Mappa Mundi called Map of Nowhere, complete with souls engaged on a Ruritanian pilgrimage to shrines labelled Microsoft and Starbucks, passing possible resting places marked ‘binge drinking’ and ‘having-it-all’. Always religiously suspicious, Perry’s map centres not on Jerusalem, but on ‘Doubt’. His British Museum show went further, emphasising his love of maps that display the emotional and irrational, and maps as empirical objects displaying the commonplace.

The centerpiece was a tapestry more than 20ft long and 9ft in length entitled Map of Truths and Beliefs. At its heart was a depiction of the museum itself, with the main rooms each named for the afterlife (Heaven, Nirvana, Hell, Valhalla, Astral Plane, Avalon and, returning to cartography for the first time in 500 years, Paradise). The embroidery covered a collection of landmarks seldom seen together on other maps from any period: Nashville, Hiroshima, Monaco, Silicon Valley, Oxford, Angkor Wat and Wembley. There were figures from the artist’s personal iconography, and symbols (walled cities, itinerant sailors, lonely citadels) that wouldn’t have looked out of place on inked medieval calfskin, if only they weren’t joined by helicopters, caravans and a nuclear power station. But they had as much mysterious right to be there as anything.

Objects you could manipulate and upset: Grayson Perry in front of a section of his Map of Truths and Beliefs.

After an evening talk at the museum I asked Perry about his devotion to maps. He said that he thought all children shared this obsession before they lost their sense of wonder. ‘I became aware of the possibility of maps as objects you could manipulate and upset,’ he said, ‘and the fact that they can tell personal stories rather than official ones.’

The gift shop offered a Grayson Perry map on a silk scarf, and it joined a growing list of map merchandise that has very little to do with getting around. A short walk from the British Museum will take you to Stanfords in Covent Garden, where the gift items suggest that cartography has reached unprecedented levels of hipness. Old-school paper maps appear as wrappers on ‘It’s A Small World’ chocolates, on a global warming world mug (the coastlines disappear when you add hot liquid) and a giant eight-sheet pack of world wallpaper. The World Map Shower Curtain proved so popular after appearances in Friends and Sex and the City that they brought out one showing the New York Subway map. And how to explain the distinct unusefulness of a map wrapped around a pencil, or the hip-flask with scraps of an old school atlas printed on it?

y y y

We should end not with the past but with the future, and this takes us back online. The biggest open-source mash-up of all is OpenStreetMap, which with its ambitions to cover the entire world with local contributors might consider itself more of a Mapipedia (though not to be confused with WikiMapia – another collaborative mapping project).

OSM began in 2004 as an alternative to Tele Atlas and Navteq, happy to be free of its regimented appearance and fees. It is truly a map of the people for the people, with volunteers tracking their area with a GPS device and a determination to plot not only the roads and landmarks that appear on other maps but also things the major players may not consider, or might regard as superfluous – a cluster of benches in a park, a newly opened store, a clever cycle route. It is often the most up-to-date map available, and increasingly benefits not just from personal on-the-ground additions but also from large datasets of aerial photography and officially licensed surveys. It’s a goodwill map, and perhaps as close as we will get to a democratic map.

The same spirit, with greater urgency, invades the work of Ushahidi, a mapping platform that began as a method of monitoring violence in Kenya in 2008 and has since expanded to become the prime cartographic site for human rights work and emergency activism. Ushahidi’s catchphrase is corny but true – Changing the World One Map at a Time – and as a mark of its influence the UN has employed the immediacy of Ushahidi mapping in its crisis response to the killings in Syria and natural disasters in Japan and India.

Ushahidi’s strength lies not only in its mapping tools, but in the ability of local people to employ them. Universal ease of use has been one of the great developments of digital cartography, and nowhere has this been more evident than in Africa, where inhabitants of the Kenyan slum region Kibera and villagers in the Congo rainforests have increased their global visibility, and with it their rights and heritage, with the aid of simple GPS and an indestructible platform with which they may place themselves on the map.

And so we are back where we started, the place where maps began to make us human. But Africa is no longer dark, the poles are no longer white, and we are fairly sure we live on a planet with more than three continents. More people use more maps than at any other time in human history, but we have not lost sight of their beauty, romance or inherent usefulness. And nor have we mislaid their stories.

There is, of course, still quite a lot to be said for getting lost. This is a harder task these days, but it’s a downside we can tolerate. We may always turn off our phones, fairly safe in the knowledge that maps will still be there when we need them. We are searching souls, and the values we long ago entrusted in maps as guides and inspirations are still vibrant in the age of the Googleplex. For when we gaze at a map – any map, in any format, from any era – we still find nothing so much as history and ourselves.