Before we begin our investigation of the special forms of morphology that Eskimo societies assume at different times of the year, we must first determine their invariant features. Despite the changes in Eskimo morphology, certain fundamental features always remain the same, and upon these depend the particular variables with which we are going to be concerned. The location of these societies and the number, nature and size of their elementary groups constitute immutable factors. The periodic variations which we are going to describe and elucidate are based on this permanent foundation. We must, therefore, first try to understand this foundation. In other words, before considering the seasonal morphology of Eskimo societies, we must determine the essential features of their general morphology.1

Eskimo are2 to be found between 78° 8’ latitude in the north (the Itah settlement at Smith Strait on the north-west coast of Greenland3) and 53° 4′ in the south, on the west coast of Hudson Bay, which is the furthest point to which Eskimo regularly travel but not where they reside.4 On the coast of Labrador, they are found up to 54° latitude and on the Pacific as far north as 56° 444′.5 The Eskimo thus cover an immense area of 22 degrees of latitude and almost 60 degrees of longitude, extending into Asia, where they have a settlement at East Cape.6

In this vast region, however, both in Asia as well as in America, they occupy only the coasts. The Eskimo are essentially a coastal people. Only a few tribes in Alaska inhabit land in the interior.7 These are the Eskimo who are settled on the Yukon delta and the Kuskokwim, and who may be considered as maritime river-dwellers.

It is possible, however, to be more precise. The Eskimo are not simply a coastal people. They are people of the water’s fringe – if we may use this term to designate all the relatively abrupt terminations of the sea coasts. This explains the marked differences between the Eskimo and other arctic peoples.8 Except for the deltas and the little-known rivers of King William Land, all the coasts that the Eskimo occupy have the same character: a more or less narrow strip of land skirting the edges of a plateau that gives way, more or less abruptly, to the sea. In Greenland, the mountains overhang the sea; and, moreover, the immense glacier which has been given the name Inlandsis (Inland Ice) leaves only a mountainous belt whose widest part (wide on account of the fiords) measures a scant 140 miles. This belt is broken by the outlets to the sea made by the inland glaciers. The fiords and the islands in the fiords are the only areas that are protected from the strong winds and, as a consequence, they enjoy a bearable temperature. They alone offer grazing land for game animals, and readily accessible areas where marine animals can catch fish or may themselves be caught.9 Like Greenland, the Melville Peninsula, Baffin Land and the northern shores of Hudson Bay also have steep, dissected coasts. Even where the interior plateau is free of glaciers, it is swept by winds and always covered by snow; it offers little habitable land except for a narrow margin along the shore, and deep valleys abutting on glacial lakes.10 Labrador has the same character, but with an interior climate that is more continental.11 The Saint Lawrence area of northern Canada and the Boothia Peninsula end in a more gentle expanse, especially at Bathurst Inlet, but, as in other regions, the interior plateau restricts to a relative minimum the area which, when seen on a map, appears as if it ought to be habitable.12 The coast to the west of the Mackenzie River has the same features from the end of the Rocky Mountains as far as the icy headland at Bering Strait. From this point all the way round to Kodiak Island, the southern limit of the Eskimo zone, there is alternately delta tundra and steep-falling mountains or plateaux.13

If the Eskimo are a coastal people, the coast is not for them what we ordinarily think of as a coast. Ratzel14 has defined ‘coasts’ in a general way as ‘the points of communication between the sea and the land or, rather, between this land and other more distant lands’. This definition does not apply to the coasts that the Eskimo inhabit.15 Between them and the land behind them there is generally very little communication. The peoples of the interior do not spend much time on the coast,16 nor do the Eskimo move far inland.17 The coast is here exclusively a habitat; it is neither a passage nor a point of transition.

After this description of the Eskimo habitat, we must consider how the Eskimo are distributed over the land they inhabit: the particular composition of their social groups, their number, size and disposition.

First, we must know something about the political groupings that comprise the Eskimo population. Do the Eskimo form distinct tribal aggregates, or a nation – a confederation of tribes? Unfortunately, besides its lack of precision, the usual terminology is difficult to apply here. Eskimo society is, by its very nature, somewhat vague and fluid and it is not easy to distinguish which fixed units make up its composition.

A distinct language is one of the surest criteria for recognizing a collectivity, either a tribe or a nation. But the Eskimo show a remarkable linguistic unity over a considerable area. Where we do have information on the boundaries between various dialects,18 which is not often, it is impossible to establish a definite connection between the area of a dialect and a specific social group. Thus, in the north of Alaska, there are two or three dialects spoken by ten or twelve groups which some observers have thought they could distinguish and to which they have applied the term ‘tribe’.19

Another criterion that distinguishes a tribe is a common name shared by all its members. But, on this point, it is clear that the tribal nomenclature is very imprecise. In Greenland, there is no mention of any name that refers to a properly-defined tribe, or, in other words, to an agglomeration of local settlements or clans.20 For Labrador, the Moravian missionaries have not recorded a single proper name. The only names that we do have are for the Ungava district on Hudson Strait, and these are extremely vague and hardly proper names at all (they refer to ‘distant people’, or ‘people of the islands’, etc.).21 It is true that in other areas there are more clearly defined lists of names.22 But with the exception of Baffin Land and the west coast of Hudson Bay, where names appear to have stayed the same and are reported identically by all authors,23 there are very serious discrepancies everywhere among observers.24

A similar vagueness also applies to boundaries. A boundary is still the clearest indication of the unity of a group who think of themselves as a political entity. But there is only one mention of this, and that applies to the least known portions of the Eskimo population.25 Tribal warfare is yet another way whereby a tribe affirms its existence and identity; but we know of no case of tribal warfare except among the central Eskimo and the Alaskan tribes for whom there exist special circumstances.26

From all these facts, we cannot conclude with complete assurance that there is absolutely no tribal organization among the Eskimo.27 On the contrary, there are a number of social aggregates that definitely appear to have some of the features which ordinarily define a tribe. Yet, at the same time, it is apparent that more often than not these aggregates assume very uncertain and inconsistent forms; it is difficult to know where they begin and where they end. They appear to merge easily and to form multiple combinations among themselves; and rarely do they come together to perform common activities. If therefore the tribe exists, it is certainly not the solid and stable social unit upon which Eskimo groups are based. The tribe, to be more precise, does not constitute a territorial unit. Its main characteristic is the constancy of relations it permits between assembled groups. Among such groups, communications are more easily maintained than if each group seized upon its own territory and identified with it and if fixed boundaries clearly distinguished different groups from their neighbours. Eskimo tribes are separated from one another by barren expanses, completely denuded and hardly habitable, with headlands round which it is impossible to navigate at any time. As a result, journeys between tribes are a rarity.28 It is indeed remarkable that the only group that gives the impression of being a proper tribe is the group of Eskimo at Smith Strait. Geographical circumstances have completely isolated it from all other groups and, although it occupies an immense area, its members form, as it were, a single family.29

The true territorial unit is, rather, the settlement.30 By this we mean a group of assembled families who are united by special ties and who occupy a habitat in which they are unevenly distributed, as we shall see, at different times of the year, but which constitutes their domain. A settlement is, thus, a concentration of houses, a collection of tent sites, plus hunting-grounds on land and sea, all of which belong to a certain number of individuals. It also includes the system of paths, passages and harbours which these individuals use and where they continually encounter one another.31 All this forms a unified whole that has all the distinct characteristics of a circumscribed social group.

(1) The settlement has a definite name.32 Although other tribal or ethnic names may fluctuate and are reported differently by various authors, the names of settlements are clearly localized and are always reported as the same. As good evidence of this, one need only compare the list of Alaskan settlements which we cite later (Appendix 1) with the one compiled by Petroff. Except for the so-called Arctic district, these lists hardly differ at all, whereas the tribal names that Porter cites are very different from those of Petroff.33

(2) The name of a settlement is a proper name used by all its members and by them alone. Ordinarily, the name consists of a descriptive place name followed by the suffix -muit (‘native of—’).34

(3) The territory of a settlement has clearly recognized boundaries. Each settlement has its grounds for hunting and fishing on land and sea.35 Tales tell of their existence.36 In Greenland, Baffin Land and in the north of Labrador, settlements are strictly localized comprising a fiord with its upland grazing lands. Elsewhere they include either an island with the coast facing it, a headland with its hinterland,37 or the bend of a river in a delta with a bit of coast, etc. Except when a major catastrophe destroys the settlement, the same people or their descendants always stay in the same spot: the descendants of Frobisher’s victims in the sixteenth century still remembered that expedition in the nineteenth century.38

(4) The settlement has more than just a name and a territory; it also possesses a linguistic unity as well as a moral and religious one. Although these two categories may appear initially to be unrelated, we have purposely linked them because the linguistic unity to which we wish to call attention has a religious basis and is related to ideas about the dead and their reincarnation. Among the Eskimo, there exists a remarkable system of taboos concerning the names of the dead, and the entire settlement must observe this taboo. It involves the radical suppression of all words contained in the proper names of deceased individuals.39 It is also a regular practice to give the name of the last person to die to the first child to be born thereafter in the settlement; the child is considered to be the reincarnation of the dead person. Thus, each locality possesses a limited number of proper names which consequently constitute an element of its physiognomy.40

In summary, with the single qualification that settlements, to a certain extent, permeate one another, we can say that each of them constitutes a fixed and defined social unit which contrasts with the chahging aspect of tribes. We must not, however, exaggerate the importance of our single qualification because, even if it is true that there is some exchange of population between settlements, this relative permeability41 or mobility is always caused by vitally urgent necessities. As a result, all variation is readily explicable; hence the rule does not seem to be violated.

We have thus shown that the settlement is the unit that provides the basis of Eskimo morphology. But if we want to be more precise in our representation of it, we must investigate the distribution of settlements in a territory, their size, and the composition of their population according to sex, age and status.

Among the Greenland tribes on which we have good information, there are few settlements. In 1821 Graah found only seventeen between Cape Farewell and Graah Island; it is unlikely that he missed any, since his expedition was carried out under reasonably good conditions.42 Since then, the number of these settlements decreased, and when Holm made his visit in 1884, nearly all had disappeared. Today the area is almost completely deserted.43 This progressive diminution has two causes. First, since 1825, European settlements in the south have attracted Eskimo from the east to Frederiksdal because of their resources and the greater protection they offered.44 Second, settlements further north have become centred upon Angmagssalik.45 It is reasonable to suppose that the retreat of the Eskimo from Scoresby Sound, which preceded the arrival of Scoresby in 1804, may have come about in the same way, but by force in this case, and not simply from self-interest.

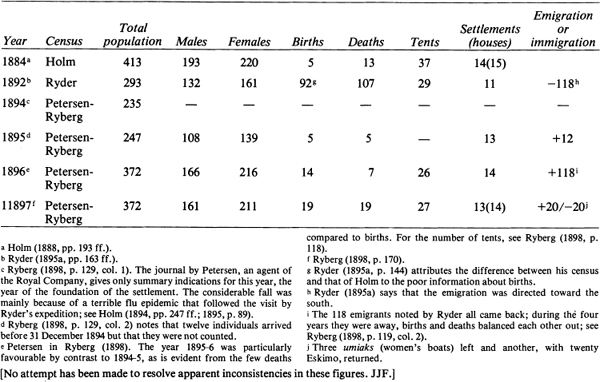

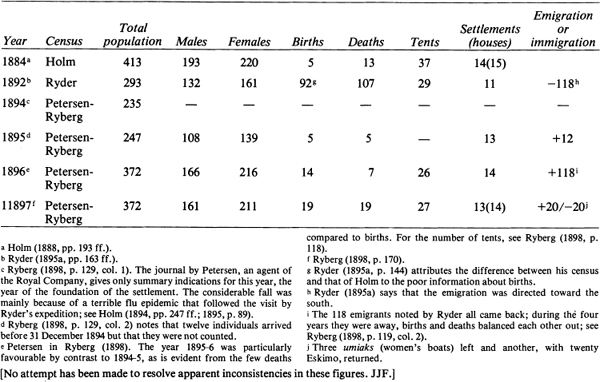

These few settlements are also small and widely separated. At Angmagssalik fiord, which comprises a considerable coastal area, there were only fourteen settlements in 1883 with a total of 413 inhabitants. Ikatek, the biggest, had fifty-eight people; the smallest, Nunakitit, had only fourteen.46 Moreover it is interesting to follow the movements of the population as indicated in Table 1. One can see how precarious and unstable is the existence of this population. In eight years from 1884 to 1892 it lost, either through death or emigration, two-thirds of its able-bodied members. In 1896 the situation was suddenly reversed by a single favourable year and through help provided by the permanent settlement of Europeans: the population rose from 247 to 372, an increase of 50 per cent.

We have very precise and detailed information on the western coast population.47 But since it dates from the period after the arrival of Europeans, we will use it only to illustrate two particular points that are equally evident at Angmagssalik.48 The first is the high level of male mortality and, as a consequence, the considerable proportion of women in the total population. In southern Greenland, from 1861 to 1891, 8.3 per cent of deaths were the result of kayak accidents; in other words, these related exclusively to men who capsized in their dangerous little boats. Only 2.3 per cent of deaths were the result of other mishaps. Another remarkable feature is the number of violent deaths. For northern Greenland, the figures are 4.3 per cent for deaths in kayaks and 5.3 for other violent deaths. For Angmagssalik, according to the information of Holm and Ryder, violent deaths among men are estimated to account for 25 to 30 per cent of the total mortality rate.49

The second point we wish to note concerns the migrations that limit the population of each settlement. The tables which Ryberg provides us for the years 1805 to 1890 demonstrate this fact for the northern districts of southern Greenland. The settlements of Godthaab and Holstenborg increase steadily to the detriment of those to the south. Similarly, we can also see how slow and, eventually, how minimal the influence of European material culture has been. In fact, for the years 1861 to 1891, the average proportion of births to deaths has been 39:40, going from 33:48 in 1860 to 44:35 in 1891.50

In Alaska, at the other end of the Eskimo region, we can see the same things. Our earliest information, which comes from the first Russian colonists, relates to the tribes of the south and is certainly neither very precise nor trustworthy and it allows only some vague estimates. But in Glasunov’s travel diary we have more circumstantial data about the Eskimo of the Kuskokwim delta, where the maximum number of people per settlement was 250.51 According to Petroff’s52 census (followed by a more reliable one by Porter which we will consider later),53 the maximum density in this region was attained by the settlements on the Togiak River. On the other hand, the Kuskowigmiut54 were the largest of all the known Eskimo tribes, though hardly the most densely settled, considering the area that they inhabited. It is worth noting that, like the Togiagmiut, this tribe settled beside rivers exceptionally rich in fish and, consequently, the people escaped certain dangers. Yet we must not exaggerate the importance of these relatively fortunate settlements. From Porter’s lists, it seems that none of them reached the size indicated by Petroff. The Kassiamiut settlement which was reported by Petroff as having 605 individuals appears not to have been a proper settlement, but, rather, a collection of villages55: which included a number of creoles and Europeans.56 Another area where settlements are also larger and closer together is the group of islands situated between the Bering Strait and the southern part of Alaska.57 And yet the density here, calculated on the basis of habitable land(?), is still very low: thirteen people per sq. kilometre.58

From all these facts it is apparent that there is a sort of natural limit to the size of Eskimo groups – a strict limit that may not be exceeded. Deaths or emigration – or the combination of these two factors – keep the Eskimo from exceeding this level. By their nature, Eskimo settlements are not large. One might almost say that the restricted size of their morphological unit is as characteristic of the Eskimo as their appearance or the common features of the dialects they speak. Thus, in the census lists, we can immediately recognize those settlements that have come under European influence or those that are not properly Eskimo: their scale noticeably exceeds the mean.59 This applies to the so-called Kassiamiut settlement which we were just discussing; it is also true of that at Port Clarence which, in fact, serves as a station for European whalers.60

The composition of a settlement is just as characteristic as its size. It comprises few old people and few children; for various reasons, Eskimo women generally have only a small number of children.61 The age pyramid rests, therefore, on a narrow base and it tends to thin sharply after sixty-five. On the other hand, the female population is considerable and, within this population, the position of widows is quite exceptional62 (see Appendix 2). The high number of widows – especially remarkable, since celibacy is almost unknown and Eskimo men prefer to marry widows rather than young girls – is almost entirely because so many men die at sea. It is important to establish these facts, to which we will return later.

We must look to the Eskimo way of life for the causes of this situation. Indeed, this is not at all difficult to understand; it is, on the contrary, a remarkable application of the laws of biophysics and of the necessary symbiotic relation among animal species. European explorers have frequently insisted that, even with European equipment, there is no better diet nor better economic system in these regions than that adopted by the Eskimo.63 They are governed by environmental circumstances. Unlike other arctic people, the Eskimo have not domesticated the reindeer;64 instead they live from hunting and fishing. Game consists of wild reindeer which are found everywhere, musk oxen, polar bears, foxes, hares, some relatively rare fur-bearing carnivores, and various species of birds: ptarmigan, crows, wild swan, penguin and small owls. But catching these animals is, to some extent, a matter of luck, and for lack of suitable techniques they cannot be hunted in winter. Therefore except for passing birds or reindeer and some chance encounters, the Eskimo live chiefly off marine animals. Cetaceans form the principal source of their subsistence. In its important varieties, the seal is the most useful animal; where there are seal, one expects to find Eskimo.65 Various species of the dolphin family, including the grampus and the white whale, are also actively hunted, as well as the walrus; the walrus mainly in the spring; the whale, even, in the autumn.66 Marine and fresh-water fish and sea-urchins also form a small portion of the diet. By relying on the kayak in open waters or by patiently waiting at ice-holes, men are able to spear marine animals with their remarkable harpoons. And they eat their flesh either raw or cooked.

Three things are required by every Eskimo group: (1) in winter, a cover of ice; (2) in spring, open waters for hunting seal; and (3) in summer, a territory for hunting and fresh water for fishing.67 These three conditions are found together only at places that are a variable distance from one another; they occur at fixed points and in limited number. Only in such places are the Eskimo able to settle. Nor do they ever settle on enclosed bodies of water:68 they have definitely withdrawn from certain coasts which, to all appearances, were once open but have since become enclosed.69 These three requirements have confined Eskimo settlements within strict limits, and an examination of some particular cases will indicate why this is so.

We may take, for example, the settlements at Angmagssalik,70 which is situated on the eastern coast of Greenland at a relatively low latitude. The coast is blocked by ice as far as the 70° parallel. This mass of ice is maintained by the polar current that descends from Spitzbergen, passes through the Denmark Strait and goes on to Cape Farewell and Davis Strait. From the east, the coast is unapproachable; but at this relatively low latitude there is enough sunlight in summer to clear the sea over a sufficient area for hunting. Yet these conditions are unstable and precarious. The sea may not become ice-free; the supply of game animals is quickly exhausted and, on the winter ice, they are difficult to catch. Then again, the limited area of open water and the danger of icebergs which are continually being detached from the ice cap prevent groups from moving easily beyond the vicinity of the fiords. They must stay near those places that combine all the necessary conditions for their existence. If some accident occurs, or if one of their usual resources happens to fail, they cannot easily search a little further on for what they need. They must immediately move some distance to another likely spot, and these long migrations are not undertaken without great risks and without the loss of lives. We can see why, under these conditions, it would be impossible for groups to reach a large size. Anything that exceeds a certain limit, any imprudent modification of implacable physical laws or any unfortunate combination of weather conditions, has, as its fatal consequence, a reduction of the population. If the ice along the coast is late in melting, seal-hunting becomes impossible. If it melts too quickly because of a strong Föhn wind, then it is impossible to venture out in a kayak or to hunt on the ice: since it has begun to thaw, seal and walrus no longer surface. If people try to go north or south without all conditions being just right, then, sadly, the umiak (women’s boat) with several families on board may sink.71 If, driven to extremes, the Eskimo eat their dogs, they only increase their misery because travel by sledge over the snow and ice then becomes impossible.72

Let us move now to Point Barrow,73 the northernmost point on the American coast. Here we see the same situation. Although the sea is rarely closed, it is also rarely free of ice. All the Europeans who have been there say that the marine and terrestrial game is just sufficient for the population. Hunting presents continual risks which the Eskimo know how to avert only by religious means; indeed, hunting is a constant danger which even the use of firearms has not yet eliminated. Population size is thus limited by the nature of things. It is so exactly in balance with food resources that these cannot diminish, however slightly, without causing a significant decrease in the population. From 1851 to 1881 the population was halved: this large reduction was the result of the fact that whale-hunting became less bountiful after the establishment of European whalers.74

To sum up, we can see that the limitation on Eskimo settlements depends on the way in which the environment acts, not on the individual, but on the group as a whole.75