BACK UP THE U-HAUL

King of Egypt

Born: Egypt, circa 1342 BC

Died: Egypt, 1323 BC 19 years old

KING TUT IS more famous for being dead than alive. He was a blip in Egyptian history until 1922, when some explorers hit pay dirt and found his three-thousand-year-old mummy nestled inside a giant sarcophagus. That sounds like a human body part, but it’s just a fancy word meaning a stone box for a dead body. These grave-robbing explorers broke into Tut’s tomb and took all his gold. And there was a lot of it because King Tut definitely planned on being king in the afterlife. What he didn’t plan on was being probed, sliced, dismembered, X-rayed, scanned, and drilled for his DNA.

Pictures of a bird, two hooks, a comb, an arrow, a sandal strap, and a couple of speed bumps spell Tutankhamun in hieroglyphics. Today, we just call him King Tut. He is also called the Boy King. He got to be the king of Egypt when he was nine years old. He was only ten when he married Ankhsenamun, who unfortunately was his half sister, which was okay back then but would be really wrong now. Besides ruling Egypt, Tut did regular kid things like riding in chariots, throwing sticks, and firing his slingshot.

And then, poof, he died.

Even though Tut had died, he wasn’t finished. Ancient Egyptians believed there is a life after this one, so after his death Tut’s corpse was prepped for life number two. He was given the seventy-day royal mummy treatment.

So that Tut wouldn’t rot on the trip to the next life, the embalmers scooped his insides out from top to bottom. To get his brains out, a long bronze needle with a hook on the end was shoved up his nose. His brain was broken up into teeny bits and pulled out one piece at a time. The Egyptians believed the brain’s only job was to keep the ears apart, and that the heart did all the thinking.

They didn’t take Tut’s teeth, nails, and eyeballs. They left Tut’s heart in his body because he was going to need that to think. And they left his genitals so no one would mistake him for Queen Tut.

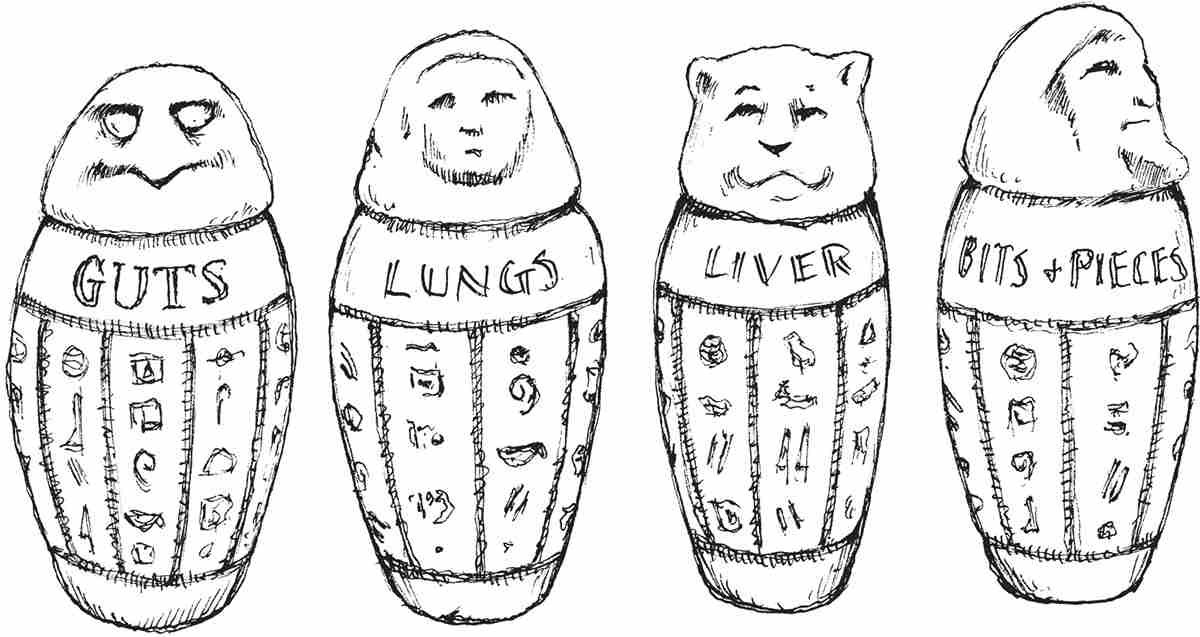

Next, they cut open Tut’s stomach and pulled out whatever they could get their hands on—like his liver, stomach, lungs, and twenty-two feet of intestines. Everything was washed, dried, put into four jars, and wrapped to go with him.

They covered Tut’s altered corpse with natron (saltlike stuff) and put it on a slanted board with grooves in it so his bodily fluids flowed directly into a tub at the end. His gutted body was completely dried, which was especially difficult considering the human body is 75 percent water. They stuffed his chest with wads of cloth to soak up the inside juice. Every weensy drop of blood, rag, and leftover bit of Tut was saved and crammed into big jars for him to take along for his next excellent adventure.

Tut’s cadaver gave new meaning to the words “stiff” and “stinky,” so it was smeared with scented goo to make it smell better and to make it feel less like Tut jerky.

Then, to make him look like a real mummy and to keep him from falling apart during a ceremony when a priest stood him up and offered him grapes, Tut’s pruned corpse was encased by half a football field worth of fabric strips spun around his body like cotton candy, along with 143 charms woven in for good luck. To seal everything, they poured warmed plant resin (sap) all over Tut’s wrapped body. Think superglue.

Meanwhile, servants picked up a few of his kingly things from the palace, including a couple of thrones, two slingshots, two jars of honey, six chariots, thirty golden statues, thirty-five model boats, 130 walking sticks, 427 arrows, and lots of sandals.

When Tut died, no one in Egypt had built a pyramid for a dead king for two hundred years because tomb raiders had trashed every single one of them, taking everything—including the mummies. Tomb raiders took off with the mother lode of ancient Egyptian history.

So they buried Tut in a tomb hidden under a sand dune in the middle of the desert known as the Valley of the Kings.

And there he rested undisturbed for three thousand years.

In 1922, Howard Carter—an English guy who had been digging around the Valley for twenty years—found Tut’s intact tomb under a trillion grains of sand. Carter took ten years to pick through Tut’s personal things and divvy them up to museums all over the world. The Egyptians told Carter, “Go home already.”

But first Carter and his team did an “autopsy.” It was hard to do because Tut was superglued to the bottom of his coffin, and his famous gold mask was attached to his head. Carter managed to figure out Tut had been a teenager when he died because his teeth hadn’t all come in yet and his leg bones weren’t fully developed.

King Tut was returned to his sarcophagus and went nighty-night back in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings for about forty more years.

In 1968, experts X-rayed Tut’s mummy to figure out how he had died. They noticed Tut’s breastbone, genitals, one thumb, and a few ribs were missing. The X-rays also showed that his vertebrae were fused together and his skull was misshapen. They analyzed the facts and announced, “King Tut was murdered!”

Historians took the murder theory and fit the facts to the crime. Egyptologists had a new angle, history books were rewritten, and museum exhibits were revamped.

Tut stayed put for ten more years, until scientists removed him from his stone box again in 1978. He was still dead. They took more X-rays but never published their findings. And from a bone sample, they analyzed his blood. Tut’s blood types were A2 and MN.

In 2005, there was new equipment to try out on Tut: a CT scan (way better than an X-ray). That was the first time anyone got a good look at what Carter forgot to mention after his so-called autopsy. He had broken off Tut’s arms and legs and sliced Tut’s chest down the middle. Carter also chiseled Tut’s head off to get it free of the solid-gold mask. And to get Tut’s 143 good-luck charms, Carter cut the body wrapping with an X-Acto blade. Afterward he glued Tut back together with wax and put the mangled mummy in a bed of sand. He didn’t bother to reattach Tut’s genitals, thumb, and ribs; he just buried them in the sand. And then he put Tut back inside the coffin.

Carter was just another tomb raider after all.

The CT scan showed that Tut had an overbite, a small cleft palate, and a bend in his spine. But there was something else: Tut had a broken leg, and this one was not Carter’s doing.

The Boy King got a new obit—“Tut died of a broken leg that got infected.” He went back into his stone box—but not for long.

In 2009, scientists took a sample of Tut’s DNA out of his bones. His genetic fingerprint showed he had Koehler disease, which diminished the blood supply to the bones in his left foot, meaning he had kind of a dead foot. The 130 walking sticks packed in his tomb were there because he was going to need them in the afterlife, just as he needed them in this one. But that’s not what killed him.

Tut had malaria, a disease you get after being bitten by an infected mosquito. Malaria, along with his broken leg and dead foot, made for a dead king.

He died in 1323 BC. He was only nineteen years old. It didn’t take a CT scan to see that Tut’s leg was broken; it was visible to the naked eye and mentioned in Carter’s original autopsy. It was also noted that Tut had a scabby, discolored indentation on the left side of his face. At the time, no one really knew what a three-thousand-year-old insect bite might look like, but now that we know Tut died of malaria, that scab on his face could be the mosquito bite that eventually killed him.

Tut’s mummy is back in his tomb. Maybe now he can rest in peace. But for how long?

THINGS TO DO WITH OLD MUMMIES

PHARAOHS AND MILLIONS OF COMMON people were mummified in ancient times. Later, mummies were shipped by the ton all over the world for other uses, including:

1. MUMMY MEDICINE

For hundreds of years (1300–1800) doctors believed burned and pulverized mummies made into oils and powders could cure:

| abscesses |

paralysis |

| coughs |

poisoning |

| epilepsy |

rashes |

| fractures |

ulcers |

| palpitations |

|

SIDE EFFECTS OF SWALLOWING MUMMY MEDICINE

• serious vomiting

• evil-smelling breath

2. MUMMY PAPER

Every mummy has at least thirty pounds of cloth around it. Used mummy cloth was made into brown butcher paper in the mid-1800s for packaging meat (unbeknownst to shoppers). But fairly soon, mummy paper was discontinued—after an outbreak of cholera among the workers at the paper mill.

3. MUMMY PAINT

Ground-up mummy produced a deep brown favored by Romantic painters (1790–1850). There were problems with this paint:

•It never dried.

•It dripped down the painting in hot weather.

•It contracted and cracked in cold weather.

•It ruined any color under, over, or near it.

MUMMY EYEBALLS

MUMMY EYE SOCKETS LOOK EMPTY, but they’re not. Eyeballs shrink to almost nothing during the drying process. The empty-looking sockets were sometimes filled with cloth, onions, or stones and painted to look like eyeballs.

COOL FACT

If mummy eyeballs are rehydrated, they return to almost normal size.

KING TUT UNDER GLASS

TUT’S MUMMY WAS REMOVED FROM its sarcophagus and placed in a climate-controlled glass case in Tut’s tomb, which was open for viewing for the first time in 2007. The mummy has been examined five times in the past, but only now is the public able to view it.