YOU GLOW, GIRL

Physicist and Chemist

Born: Warsaw, Poland, November 7, 1867

Died: Savoy, France, July 4, 1934 66 years old

TO SAY THAT science was Marie Curie’s life is an understatement. Science was more important to her than people, money, sleeping, and eating. She definitely wasn’t the woman you called to have a bunch of laughs with. She couldn’t. She had to be a superwoman to make it in the male-dominated field of science.

One day, Marie saw something glowing on this stuff called uranium. She wanted to know, what’s that? To figure out what was glowing, Marie had eight tons of mountainous rubble known as pitchblende hauled in carts and dumped at the door of her school lab. It took Marie four years to boil, coax, and reduce this glowing pile down to one-fifth of a teaspoon of pure magic. Imagine that. She had turned a mountain into a molehill of radium. She called it “my child.” Marie Curie gave life to a new element, but that element drained the life out of her.

Marie was born in Poland. Her life theory was: work slowly, never forget anything, and never make a mistake. The word “leisure” was not in her vocabulary. She went to the Sorbonne in France because there was no such thing as college for girls in Poland. Although she was pretty, she didn’t care that her clothes were shabby or that she lived in a dump—all that mattered were her grades.

Marie met the French scientist Pierre Curie. They talked about crystallography and piezoelectric quartz and other romantic things that only the two of them could comprehend, and they got married. Her wedding dress wasn’t white; it was dark and practical so that afterward she could wear it straight to the lab. They had two children, but Marie spent more time with her radium child than with her own girls.

Marie worked with radium day in and day out for almost nine years. Radium was beautiful. It glowed with supernatural energy, as if fairies had touched it. It was radioactive. It could help cure cancer.

Marie and Pierre won the Nobel Prize in physics together with Antoine Henri Becquerel. But the Curies were too sick to pick up their prize. Marie had lost fifteen pounds, her fingertips were black, and her face looked like it was dusted with flour. And Pierre could barely walk.

One day, Pierre couldn’t get out of the way of a horse-drawn cab, and he was killed.

Marie’s life and lab partner was gone, and she was heartbroken. But she was also a maniac workaholic, so she went right back to work. She became the first woman professor at the Sorbonne, and she taught Radioactivity 101.

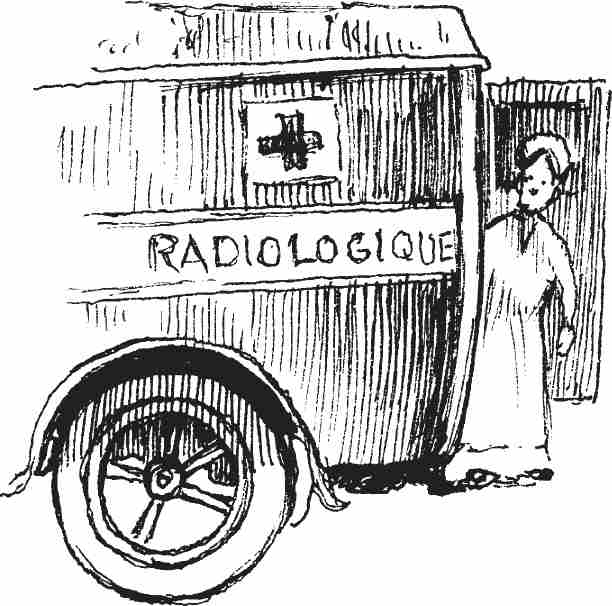

Superwoman Marie won her second Nobel Prize, this time for chemistry. And then she spent a few years driving X-ray machines around in a truck during World War I, helping doctors locate bullets inside wounded soldiers. Back at the lab, with a beaker and a Bunsen burner, she tried to find uses for radioactive materials in medicine.

But Marie was in need of some medicine herself. Her blackened fingertips were cracked and oozing, and she incessantly rubbed them together. There was a loud buzz in her ears, and she looked like a bag of bones in a ghost mask. Double cataracts made her practically blind. Like I was saying, no laughs here.

It wasn’t just Marie who was getting sick. One of her radioactivity students had his whole arm amputated. Fifteen young women who had painted radium on clock dials died.

Marie was losing her power. She was running dangerously short of the red blood cells that carried oxygen to her muscles and brain. Her entire body hurt, and her smart thinking was becoming not so smart.

Marie ignored the obvious: radium was kryptonite to superwoman Curie; it depleted her power. But she kept holding test tubes with her bare hands and using a straw in her mouth to move toxic ingredients from vessel to vessel.

One day at the lab, Marie spiked a fever that even she couldn’t ignore. Her whole body stalled out; her bone marrow had shut down. She was running on her last tank of blood, and there’d be no more fill-ups.

Marie Curie died in France on July 4, 1934. The cause of death was aplastic anemia caused by continuous exposure to radiation. She was sixty-six years old.

Marie never let on whether she knew that her beautiful glowing child had killed her. Except maybe on her deathbed. She kept saying that all she needed to recover was a dose of fresh air. She was right . . . it was just way too late.

To this day, Marie Curie continues to be a glowing beacon for girls pursuing a life in science—along with her work desk, which will glow for fifteen hundred years to come.

APLASTIC ANEMIA

THIS IS A CONDITION IN which bone marrow does not make enough new cells to replenish the blood. It causes lower counts in red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. Symptoms include lack of energy, unhealthy paleness, palpitations, and easy bruising.

The most common cause is exposure to toxins and unprotected exposure to radioactive material.

RADIOLUMINESCENT PAINT

RADIOLUMINESCENT PAINT GLOWED IN THE dark. It was made of radioactive material mixed with luminescent crystalline powder.

It was first used in 1902 to paint clock dials. By 1920 more than four million watches and clocks had been painted. Also painted were house numbers, bedroom slippers, fish bait, theater seat numbers, pistol sights, and eyes on dolls.

Radioactive materials in paint have been discontinued since the 1970s.

MARIE CURIE IN MEMORIAM

“Her strength, her purity of will, her austerity toward herself, her objectivity, her incorruptible judgment—all these were of a kind seldom found joined in a single individual. . . . Once she had recognized a certain way as the right one, she pursued it without compromise and with extreme tenacity.”

—ALBERT EINSTEIN, Curie Memorial Celebration at the Roerich Museum, New York, November 23, 1935