NOT SO LONG AGO, a successful entrepreneur who was a student of mine (“Sam”) found himself at the tragic end of a true reversal of fortune.1 It had all started out so well. A year earlier he had received a call from one of the largest retailers in the United States, asking whether he would be interested in earning some extra revenue. There was no catch. The retailer had decided to switch suppliers for one unique type of apparel, and the new supplier was an overseas Asian company. The retailer had never worked with this Asian company before and reached out to my student for help. Sam already had a good business relationship with the retailer, and although he did not know the Asian company either, he was very familiar with the manufacturing landscape where the company was located. The retailer wanted Sam’s company to act as an intermediary between them and this Asian company. For almost no work at all other than coordinating the purchase and sale of product, he would get a percentage of each transaction that took place. If all went well, Sam’s company stood to make over a million dollars each year—a sizable amount of money for him.

The celebrations did not last long. Just a few months into the relationship, Sam received a letter from a US manufacturer. The letter claimed that in making this apparel, the Asian company had violated the US manufacturer’s patent. Given the nature of the relationship between the parties, the US manufacturer was suing the retailer, the Asian company, and Sam. The US manufacturer was open to settling out of court, but was demanding a huge settlement. Legally, the retailer was in a very safe position and had no incentive to negotiate. For practical reasons, the Asian company could not easily be made to pay through litigation. This left only my student squarely in the crosshairs. And the US manufacturer was going to come at Sam with everything they had—because this wasn’t just about patent infringement. The US manufacturer had been the original supplier of this apparel to the retailer until the Asian company had come into the picture and undercut them on price. They were not happy.

Sam did not want to pay millions in a settlement, but he also did not want to go through a legal battle. He decided to reach out to his allies in this mess, in the hope that one or both of them would be willing to chip in money to help settle the matter. The retailer was very sympathetic and felt bad that Sam had been dragged into this, but while they offered to vouch for him in legal proceedings, they were unwilling to offer any money. The Asian company argued that there was no patent infringement so there was no reason for them to offer money, an easy thing for them to say given they were outside the reach of the law. He was on his own. He asked his lawyers to reach out to the US manufacturer and explain that although he was clearly innocent in this matter, he was willing to settle for a few hundred thousand dollars, a goodwill gesture aimed at helping everyone avoid court. It did not work. They went to court.

After seven months and $400,000 in legal fees, the court ruled in favor of the US manufacturer. Sam was asked to pay almost $2 million, which was more than four times as much as he’d made in the deal before it had come to a halt due to the lawsuit. His only options now were to pay the money, to appeal the decision, or to try again to settle out of court. Paying up would be extremely costly. An out-of-court settlement would be even harder now than it had been last time, given the US manufacturer’s legal victory. The lawyers believed an appeal made the most sense, but they did not pretend his chances were good. Which route to take? You’ve already lost once in court, the other side has the leverage, you are facing a multimillion-dollar loss, none of your allies are coming to your aid, and the party on the other side of the dispute seems out for blood. What now?

As Sam tells the story, he was sitting around one day when the thought came to him: What would my negotiations professor advise? It did not take long to come up with an answer. Look for the value-maximizing outcome. In other words, given the interests, constraints, and alternatives of all the parties, what approach or outcome would create the most amount of total value in this situation? Before worrying too much about how you will get there, first figure out what the optimal deal would be. So he started to map out the negotiation space and think this through.

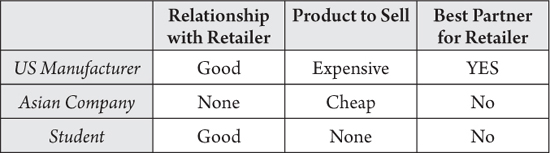

In the very beginning, the retailer’s relationship with each of the three parties had been as follows:

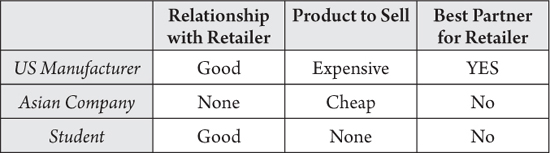

After the Asian company undercut the US manufacturer with the help of my student, the situation changed:

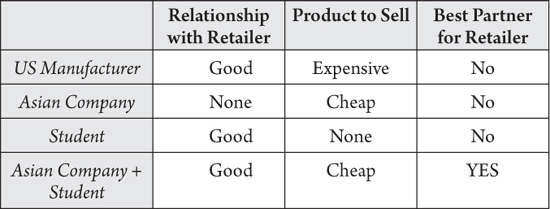

Once the Asian company’s patent infringement was revealed, and after the US manufacturer sued the other three parties, things changed again. The US manufacturer’s relationship with the retailer was now bad, and the Asian company’s product was no longer viable for sale in the United States.

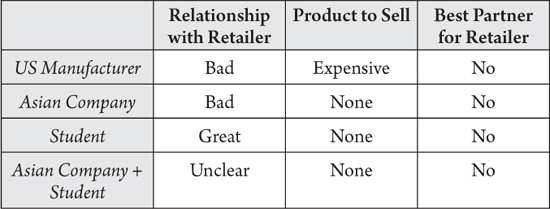

The value maximizing outcome was starting to come into focus. The US manufacturer had the power to squeeze money out of Sam, but there was an even bigger pot of money that was now missing from the entire equation: no one was capable of selling any product to the retailer. The lawsuit could yield a few million dollars for the US manufacturer, but many more millions in value were being destroyed because no one had the necessary combination of assets: a good relationship with the retailer plus a product to sell. But there was one possible entity that could bring both assets to the table: it would be a partnership between the US manufacturer and Sam. Might this work?

Sam called up the CEO of the US manufacturing firm and told him that he was getting on a plane to come and see him. “I have an idea I’d like to share with you. If I can’t convince you in 20 minutes, I will fly right back.” The CEO agreed to meet. On the way to the meeting, my student also called up his contacts at the retailer to share the broad outlines of what he planned to propose. They gave him the go-ahead to try to structure such an arrangement.

In the CEO’s office, Sam explained his analysis and the idea. The retailer would never buy directly from a company that had sued it, but the manufacturer’s patented product was a good one and there was no substitute supplier. Sam had a good relationship with the retailer, not to mention the retailer felt they owed him for putting him through the terrible ordeal. Sam could be the intermediary between the manufacturer and the retailer. The manufacturer would have to make a few concessions to the retailer to smooth things over, but a deal was possible. The two sides crunched some numbers, haggled a bit, and then came to the following agreement: (a) Sam would pay the manufacturer a few hundred thousand dollars upfront, partly to reimburse the manufacturer’s legal costs; (b) Sam would become the exclusive intermediary between the manufacturer and the retailer—this would be worth a couple million dollars to his company in the coming years; (c) Sam would become the exclusive distributor for the US manufacturer for overseas sales—another valuable win for him.

All three parties signed off, and the reversal of fortune had been reversed once more.

When someone sues you, how are you likely to view them? Most people would see that person as an enemy, or at least as an adversary. This is understandable, but potentially dangerous, because we tend to think and act differently based on how we view the person on the other side of the table. We typically have lower tolerance, less hope, and a reduced willingness to engage constructively with our enemies. And this tendency can be costly—to us and to them.

In the martial arts dojo where I practiced, it was not uncommon during class to hear students ask questions such as: What if your opponent is bigger? What if your opponent grabs you like this? What if your opponent … ?

Such statements always invited a caveat by our instructor. “They are partners, not opponents,” he would correct his students any time they used the word “opponent” to describe the person they were practicing with in class. “Remember that the people you are sparring with are there to help you learn. How will you learn from them if you think of them as opponents?” Often, he would take it a step further: “Even the person who attacks you on the street is your partner. How will you remember to stay calm, or attempt to resolve the situation without fighting, if you think of him as an opponent?”

The same is true in deadlocks and in ugly conflicts. As my student’s experience illustrates, it can be dangerous to see others one-dimensionally, and especially to label them as an opponent or enemy. If you pigeon-hole someone based on their prior behavior, you may miss opportunities that emerge when the game changes. In this case, the US manufacturer started out a stranger, turned into an adversary, and ended up an ally. The Asian company went from being a strategic asset to a legal liability in a matter of months. The biggest obstacle to solving Sam’s problem may have been the inability—at first—to see that situations change and that people can outgrow their labels.

Labels might provide an efficient means of describing someone (“she’s my competitor”), but they are necessarily incomplete and limiting. It is always best to remember that the people you are dealing with are not competitors, allies, enemies, or friends—they are just people who, like you, have interests, constraints, alternatives, and perspectives (ICAP). As a negotiator, your job is to understand these factors and to address the situation accordingly. In my negotiating, I still find it useful to retain the label partner for everyone (whether they are acting like a “friend” or “foe”), because it reminds me to have empathy, to be open to the possibility of collaboration in even the most difficult relationships, and to shed assumptions about what is or is not possible.

In the world of business, negotiators often talk about “creating value.” It is a reminder that there may be ways to improve the deal for everyone, or at least to improve it for some people without hurting others. Deal makers should obviously try to improve agreements and create more value. After all, would you rather be arguing over how to share $100 or $200? It is easier to find a solution, not to mention more profitable, when there is more to gain from reaching a deal, or more to lose from no deal.

The same principle holds in all negotiations—that is to say, in all areas of human interaction. Negotiators should be in the business of creating value whether they are bargaining over deal terms, facing deadlock, or addressing an ugly conflict. In relatively simple situations it is easy to see what is necessary to create value. For example, in the NFL or NHL, you create value when you end a strike or lockout because only by playing games can you bring money into the system (from viewers, advertisers, etc.) that you can share. To achieve this, you need to solve some difficult problems, such as agreeing on revenue split, but now you have clarity on the direction in which you should move.

It’s not so easy when the situation is complex: when there are many parties, many divergent interests, competing intuitions about the right strategy, or a lack of clarity or consensus on what the goal should even be. For example, it was not obvious what Sam should have been even trying to accomplish. Minimize the cost of settlement? Find a way to win in court? Appeal to the manufacturer’s goodwill? Leave it to the lawyers? Find a way to pressure the Asian company?

In such situations, an effective way to clarify objectives and choose between options is to ask: What would be the value-maximizing solution? Focusing on this principle immediately helped shift the student’s attention to the idea that it might be possible to make everyone better off, and that it was unwise to start off assuming the conflict was a zero-sum situation. Thinking in terms of value creation also helped to increase the set of visible options. For example, creating a business relationship with the person who is suing you is not intuitive, unless you are dispassionately looking to create value in every situation. Here again, we see the value of regarding all other parties as partners, not opponents, in the process. When you see them as your partner, you are more likely to identify and implement value-creating solutions to the problem.

One of the reasons people fail to focus on unlocking value is because the situation seems impossible. They are already so sure there is no good solution that they fail to consider the possibility of a great one. This type of thinking can sometimes be changed. One of my executive students was the president of his family business. His father, who owned 90% of the business, was still heavily involved, although he had officially retired. After years of conflict over matters big and small, the son had decided to talk with his father about how to move forward given the bad and worsening situation. The father was constantly overriding the son’s decisions and getting involved in matters where he did not have enough information. He was also making it difficult for the son to get out of his shadow and be seen as a legitimate president in the eyes of employees and customers. The conversation was likely to be ugly. It had come to the point where the son felt he would have to leave the business or ask his father to step away, and no matter what, he expected there to be anger, resentment, and potentially, a worsening of the conflict. He was dreading it. He was unsure how to start the conversation, which issues to bring up, or what outcome he even preferred.

When I heard his story and his prediction of disaster, my first question was this: Is there any possibility that both of you will walk away from the conversation happier than you had been before talking? He was quiet. He then told me he had never even considered the possibility. I said to him, “Imagine a world in which both of you are glad that the conversation happened. And now paint me a picture. What would that world look like?” And then the conversation changed. He started talking about how his father might be feeling as he thought about his retirement after decades of building a business. He spoke with regret about how little time they spent together outside of work because neither of them wanted another fight. He wondered whether his father was also longing to have this conversation. He was still not sure what the right solution would be, but he was much more confident that he would be able to go in with an open mind and have a potentially value-creating conversation. I do not know how this particular story ended, but before he left the executive program to go back to his business, the student told me that he was looking forward to seeing and talking with his father.

The same approach can also help when you are facing intransigence. In business deals, for example, when the other side says something cannot be done, or that they are unable to accept our request, I might say to them as I did to my student, “Imagine a world in which you were able to say ‘yes.’ And paint me a picture. What would that world look like?” This helps shift the conversation from what cannot be done to why it cannot be done. There are times, especially when an agreement seems unlikely, when even the people saying no have not carefully thought through exactly what would allow them to accept what is currently unacceptable. Of course, sometimes this conversation still leads to a dead end. But other times, they bring up concerns or obstacles that we are actually able to address in ways they would not have anticipated. At the very least, we get clarity on what needs to change if we want to revisit the possibility of a deal in the future.

By seeing the other side as a partner rather than an opponent, by focusing on the principle of value creation, and by pushing others to challenge their own assumptions about what is possible, you increase the possibility of breaking deadlock and resolving ugly conflict. Of course, you might still need to knock down barriers, manage the process, help the other side sell the deal, and so on, but you will have a better understanding of where you are going and the steps you need to take.

I end this section with some thoughts on what many would consider to be the ugliest of situations—those that are rife with long-standing mistrust, deep hostility, and a protracted history of grievances. We will consider some of the reasons why extremely divergent perspectives can persist, sometimes for generations, and how we might change our approach and perspective when dealing with seemingly intractable conflicts.